I had not been in the Temple Church for over 45 years. It is a place I have wanted to visit again, however until this summer, I had not made the effort to turn off Fleet Street and walk down the alley when the church was open.

The time of my last visit was as a small child, on one of the many London walks with our parents. My memories of the church are of a dark, mysterious interior – a black and white vision of the church. memories probably distorted by a child’s view and the passage of time.

Finally, this year, on a glorious summer day (good to remember just after the shortest day of the year), I did turn off Fleet Street and walk down the short alley to the Temple Church to see if it was the same as the vague memories of my only other visit.

The entrance to the alley that leads to the church is through a stone archway that occupies one half of the ground floor of a four storey building. On leaving the archway and entering the open alley we are in a place that is very different from the noise and traffic of Fleet Street, just a short distance behind:

The initial view of the round tower, probably the most distinctive feature of the church:

All that remains of the churchyard on the northern side of the church:

The round tower:

The Temple Church was built by the Knights Templar in the 12th century and the round tower was consecrated by Heraclius, the Patriarch of Jerusalem in 1185. The design of the round tower was intended to resemble the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

The chancel was added in 1240.

The Temple Church is a Royal Peculiar, this is a church that belongs directly to the monarch, rather than belonging to a diocese as with a parish church. The lead member of clergy in the Temple Church is called the Master of the Temple, a reference to the head of the order of the Knights Templar.

Despite the 12th century origin of the church, it has undergone so much “restoration” over the centuries, including major 19th century works, that there is a very little of the original church left. The Temple Church was also very badly damaged during the last war which required considerable restoration and rebuilding work.

Writing in The Bombed Buildings of Britain (the Architectural Press) in 1942, John Summerson stated “The Temple Church is a building which has suffered such dreadful ‘restoration’ that hardly one visible stone of it can be certified as older than the first half of the 19th century”.

The church did escape the Great Fire in 1666, but soon after in 1682, according to “The New View of London” by Edward Hutton, published in 1708 the Temple Church was “beautified, and the curious wainscot screen set up. The south-west part was, in the year 1695, new built with stone. In the year 1706 the church was wholly new whitewashed, gilt, and painted within, and the pillars of the round tower wainscoted with a new battlement and buttresses on the south side, and other parts of the outside were well repaired.”

More repairs were carried out in 1737 to the north and eastern sides of the church and in 1811 more general repairs were made.

More extensive repairs were carried out in 1825 to the south side of the church and the lower part of the round tower and the earlier wainscoting was removed. Further repairs and restoration began in 1845 to remove much of the earlier “beautification” and included the lowering of the pavement back to its original level. The whitewashing was also been removed.

19th century repairs including refacing much of Temple Church using Bath stone.

One of the few parts of the Temple Church which does appear to be part of the early build of the church is the magnificent western doorway to the round tower. The difference in colour shows the difference between original and Victorian restoration – the lighter coloured three outer pillars on each side are Victorian, the inner columns are original.

Walking out of the alley, into the large open area at the southern side of the church provides a good view of the round tower:

And of the whole southern facade of the church which includes the day to day entrance into the building:

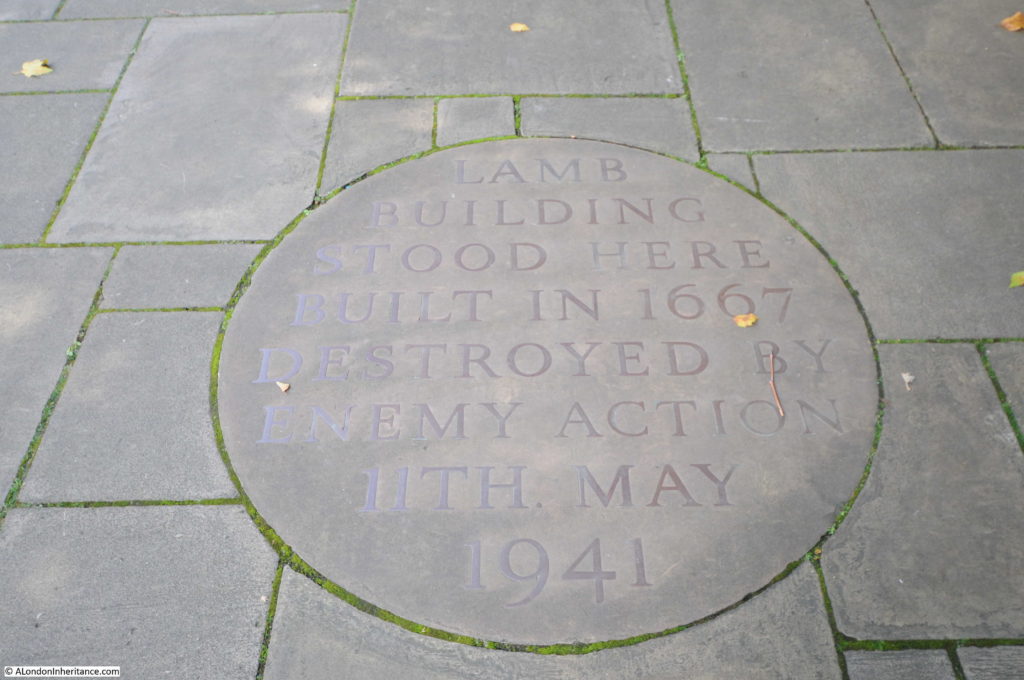

This southern view of the church was not always so open, and highlights the last time the church suffered major damage and later restoration. There is a stone plaque among the paving slabs recording the loss of the Lamb Building that had been built in 1667 and was destroyed in 1941:

The Lamb Building as it was in the 1920s is shown in the photo below. A wonderful building, damaged to the point where it could not be rebuilt. The photo also highlights how close buildings were constructed up again the Temple Church.

The following photo is looking across from Middle Temple and shows the Temple Church in the centre between the large hall on the right and the buildings on the left. Both the Temple Church and the hall have lost their roofs and have been reduced to shells of buildings with only their outer walls remaining.

The problem I find when researching these posts is that I almost always find related interesting topics to read more about. For the Temple Church, I was looking in the Imperial War Museum archives and found a couple of paintings of the Temple Church made by artists working under the War Artists Advisory Committee (WAAC).

The WAAC was formed in 1939 and led by the National Gallery Director, Kenneth Clark. The aim was to create an artistic record of the war, and during the course of the conflict over 400 artists had worked on the project, creating around 6,000 works of art.

I plan to write a future post on the War Artists Advisory Committee – it is a fascinating body of work and portrays a different aspect of the war across London to the photographic record.

The first picture (© IWM (Art.IWM ART LD 1510) is by Henry Samuel Merritt and shows the badly damaged round tower and workers clearing rubble from around the building:

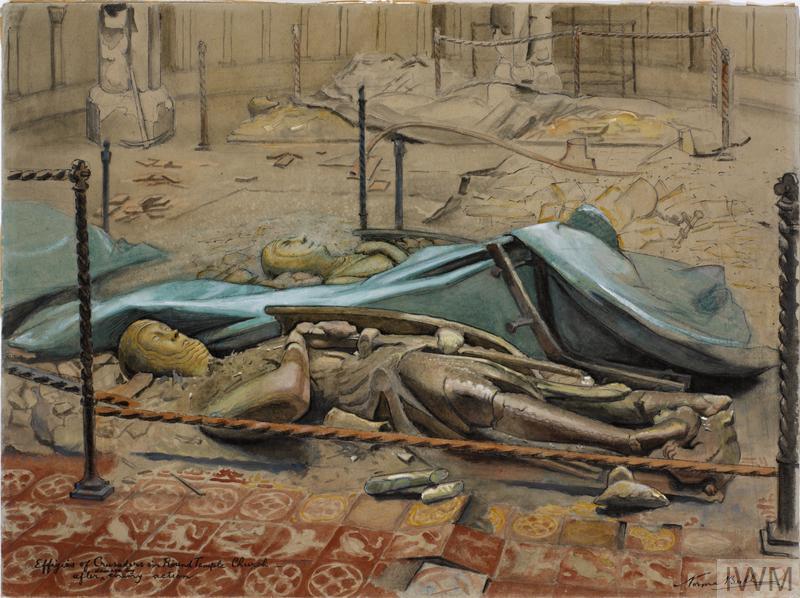

The second picture (© IWM (Art.IWM ART LD 4899) by Norma Bull shows the stone effigies of knights on the floor of the round tower. The remains of the damage caused by the bombing and fires can be seen including the broken metal railings around the effigies and cracked and broken tiling:

These pictures illustrate the level of post war rebuilding that was needed to restore the church to the standard we see today.

Having walked around the outside of the church it was time to take a look inside and see if the church resembled my black and white memories of the church from my first visit.

Walking through the door revealed a very different church, bright, colourful and showing the incredible amount of effort that went into restoring the church from the wartime shell.

This is the view looking along the chancel:

From the opposite side of the chancel:

On the floor of the round tower are the effigies of knights that I remember from my first visit and probably most captured a childhood imagination:

The effigies are of knights from the 12th and 13th centuries, some are identified, other are not, and are labelled as “Effigy of a Knight”:

The effigies suffered significant damage in 1941. The roof of the round tower collapsed onto the floor below and fires consumed all the woodwork in the church. As with the rest of the church, the effigies also required significant post war restoration.

Some of the effigies are named, although most of the reference books I have read covering the Temple Church refer to the naming as “said to be” so I suspect that due to the centuries that have passed, the periodic restoration and rebuilding of and within the church, we cannot really be sure that the effigies are named correctly.

These two are both identified as William Marshall, the 13th century first and second Earl’s of Pembroke:

The first Earl of Pembroke worked between King John and the Barons during the negotiations that ended with the Magna Carta. His son, the second Earl of Pembroke was one of the Surety Barons at Runnymede. They were both buried under the round tower.

The rebuilt roof of the round tower:

Standing by the interior side of the western door, this is the view down the length of the church, through the round tower and the chancel:

The following 1870 drawing from a similar viewpoint to the above photo shows that the post war rebuilding was faithful to the building as it was before the war:

There are a number of carved heads in the triangular spaces (spandrels) either side of the top of the arches around the edge of the round tower.

There are differing opinions as to whether any of these are original or later recreations. Simon Bradley and Nikolaus Pevsner writing in “London: The City Churches” state that the heads were renewed by Robert Smirke during one of the 19th century restorations.

Whatever their actual age, they do recreate typical medieval grotesques, caricaturing people, animals and mythical beasts.

Including combinations of people and animals with this rather painful looking biting of an ear.

The font is not that old, dating from around 1840:

This is the tomb of Edmund Plowden:

Plowden was born in 1519 and was a notable English Lawyer. As well as through the legal profession, his connection with the Temple Church was his role as Treasurer of the Temple Church from 1561 to 1570. He died in 1585 and following his directions, he was buried in the Temple Church.

The tip of the nose on the following figure on the side of Plowden’s monument indicates many years of rubbing by visitors to the church:

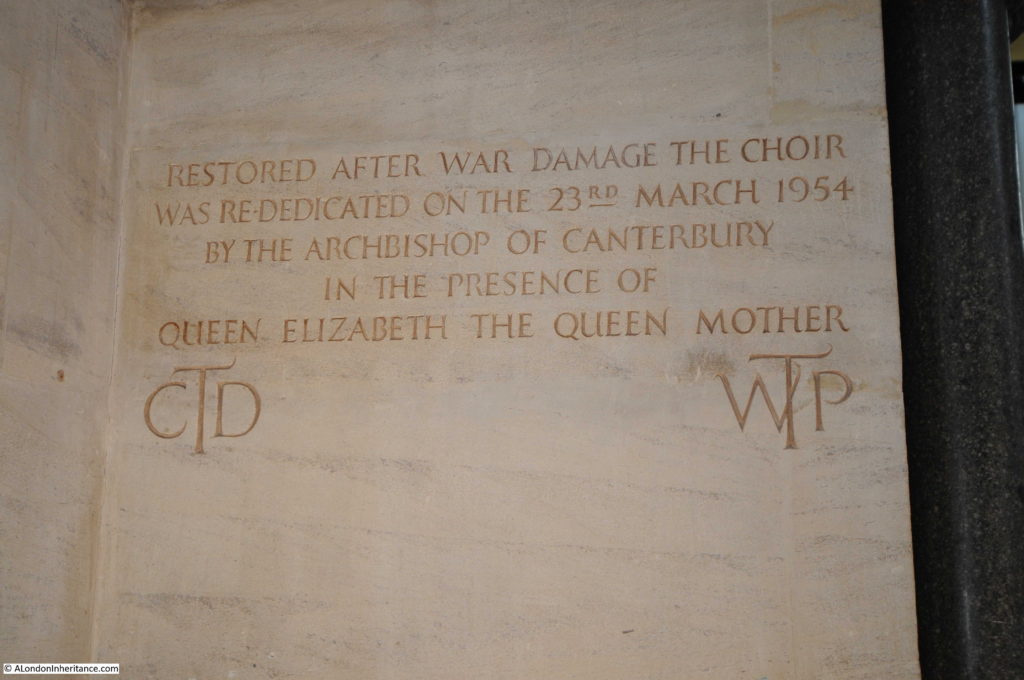

The post war rebuild of the Temple Church was significant, but was mainly completed by the mid 1950s, with stained glass being completed towards the end of the decade.

There is a carved record of the rededication of the church in 1954 in the Chancel:

Three of the stained glass windows at the eastern end of the chancel. These windows were made by Carl Edwards between 1957 and 1958. The summer sunshine really highlighted the colour and the delicate and intricate nature of these windows:

There is a door at the base of the round tower with steps that lead up to the triforium which runs around the circumference of the round tower.

The view from the round tower triforium, looking through the three arches that lead into the chancel:

Whilst there is very little left of the original church, and the building has been through so many restorations and rebuilds, perhaps the key point is that whilst the fabric has changed, Temple Church maintains the original layout, which includes the important and rare round tower. The Temple Church also provides a tangible link with the Knights Templar (who have been the subject of some fantasy writing and theories over the years), along with the Magna Carta and the legal profession of the surrounding Inner and Middle Temple.

I found the Temple Church to be very different to my distant memories of the place. Far from having a dark, black and white interior, the church is bright, colourful and fascinating.