The Flower Sellers is a statue (not sure if that is the correct word to describe this large artwork), in London Fields, Hackney. My father photographed the statue in 1989:

Last Wednesday, the first day without any rain, and with sun forecast, I went to find the Flower Sellers, and this is how they look today (unfortunately with a bright sun behind):

Most descriptions about the statue describe the installation as being in the 1980s, which I think I can narrow down to 1988.

The two figures are holding baskets possibly of flowers (which makes sense given the name of the work), but may also contain other produce. Around the base of the work, and in the surroundings of the Flower Sellers there are a number of sheep. I will come onto the reasons for these later in the post.

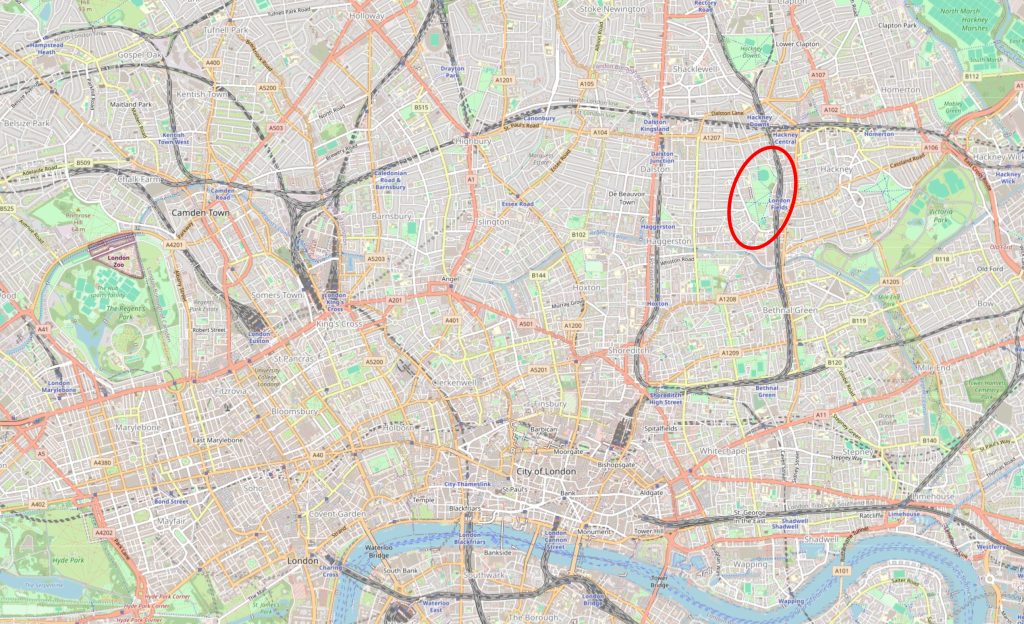

London Fields is a large area of open space in Hackney, just to the west of the Weaver line station, also called London Fields. I have circled London Fields in the following map (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

Surrounding the main statue, there are a number of stone seats, each with the top made up of colourful mosaics, depicting everyday items, such as scissors, threads of cotton, and bottles in the following example:

The name of the work is the Flower Sellers, and presumably it is flowers that are meant to be represented within the baskets held by the two people. I am not so sure. There are very few direct references to the baskets holding flowers, some references are to “different produce” sold in the nearby Broadway Market.

In 2018, after 30 years of being exposed to the elements, the work was in need of some repair, and the council commissioned local mosaic artist Tamara Froud from MosaicAllsorts to carry out the work. Today, the items in the baskets do look a bit like colourful flowers, but this could have been the result of the restoration emphasising the patterns and colours:

In my father’s 1989 photo, the items in the baskets were very plain and lacking any colour. The photo was only a year or less, after the work was installed, so perhaps the contents of the baskets were still to be finished.

The work does have a direct reference to a previous use of London Fields. The work consists of a number of seats in the immediate area of the central figures, and these follow the designs at the base of the figures, with colourful mosaic topped seating, and sheep:

These sheep, around the seating and at the base of the central work represent the time when London Fields were used as a stopping off place for animals being taken to the markets of London.

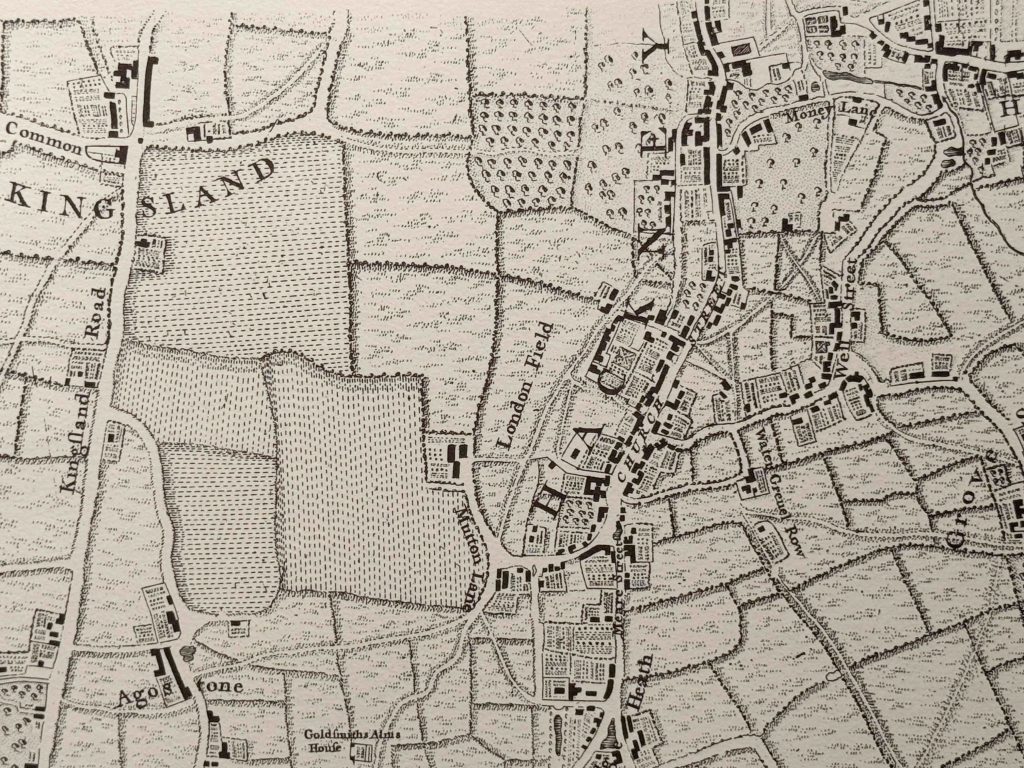

Rocque’s map of 1746 shows London Field as an area of open space (in the centre of the following map) to the west of Church Street (today Mare Street). Ribbon development along Mare Street of the village of Hackney, with the village surrounded by fields:

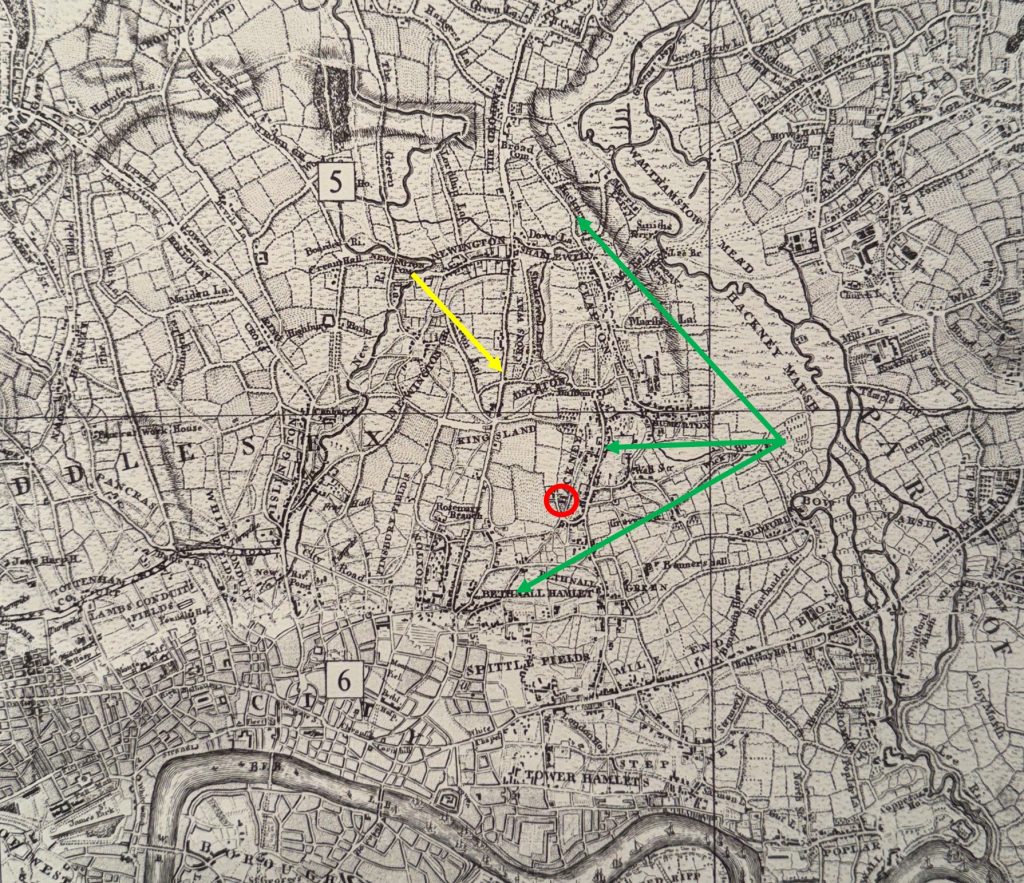

The following larger extract from Rocque’s map shows where London Fields is located (red circle) with respect to the main routes from the north of the city down to Smithfield Market. The yellow arrow points to the main route, now the A10, Kingsland Road, and the green arrows point to a detour from this road that passes through Hackney, where sheep could be rested at London Fields, before re-joining the main route to head to the market:

Volume 10 covering Hackney from “A History of the County of Middlesex”, describes London Fields being first record in 1540, with the singular use of the name, with Fields seeming to become more frequent in later centuries.

There are references to the area being worn bare by the grazing of sheep.

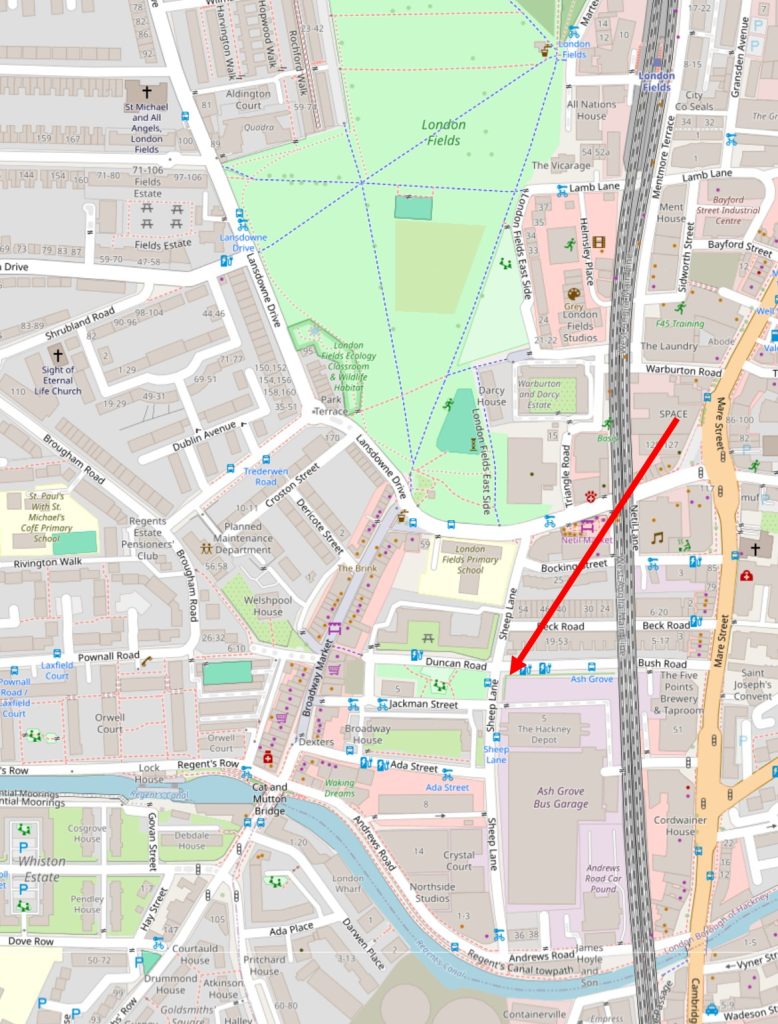

Other references to this activity were, and some still are, to be found surrounding London Fields. There was a Mutton Lane (look to the lower left of London Fields in the first extract from Rocque’s map above), and there was, and still is a Sheep Lane, as seen in the following map (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

There is also a Cat and Mutton pub at the London Fields end of Broadway Market, and crossing the Regent’s Canal is the Cat and Mutton Bridge.

As could probably be expected in an open area, with lots of travellers passing through, there was a significant amount of crime in and around London Fields.

The following is a small sample of newspaper reports mentioning London Fields from the decades in the mid 18th century around the time of Rocque’s map:

7th of October 1741: “On Thursday Night, between Seven and Eight o’clock, five Persons, singly, were robbed between the Goldsmiths Alms houses and London Field, going to Hackney, by three Footpads, who have for some time infested those Parts.”

30th of July 1730: “Monday afternoon the following acts were committed by a man with one arm, very genteelly dressed – with his sword he wounded two ladies in London Field, Hackney; and a short time afterwards, with the same weapon, he twice stabbed a gentleman upon Dalton Downs.”

17th of October 1750: “Yesterday as a Servant of a Mercer in Cheapside, who had been to deliver some Good’s at a Lady’s at Hackney, was returning home about Five o’clock in the Evening, he was stopt between London Field and the Road by a Man genteelly dressed in a light coloured Coat and black Waistcoat, who seized him by the Collar, and presenting a Pistol to him, threatened to blow his Brains out if he did not deliver his Money, which he did, to the Amount of Twenty Shillings and Three-pence, and the Fellow was going away; but on the Servant’s desiring him to return the Half-pence for a Pint of Beer, he gave him three Half pence, then took of his Hat and Wig and tripped up the man’s heels and pushed him into a Ditch, and then made off across the Field.”

4th of December 1753: “On Tuesday Night, between Seven and Eight o’clock, Mr, Cornelius Mussell was robbed in London Field, Hackney, of twenty five shillings, by five men armed with Pistols and Cutlasses; and last Night, two Gentlemen in a Coach coming to Town from Hackney, were robbed on Cambridge Heath supposed to be the same Gang.”

13th of November 1770: “Last Night an out door Clerk belonging to Mr. Pearson, Wine and Brandy Merchant, in Spitalfields, who had been at a Public House in Hackney, receiving cash to the amount of £30, was stopped by two Footpads in London Field, who robbed him of all the Money he had received.”

On the 25th of February 1773, Thomas Bond was convicted at the Old Bailey for robbing Thomas Sayville of his watch and money in London Field, Hackney – he was initially sentenced to death, but this was commuted to transportation.

The threat of a death sentence, or transportation seems to have been very little deterrent to these types of crimes given the very high number of robberies that were reported across London.

There were other strange events in London Fields, including:

31st July 1789: “Monday evening a battle was fought in London Fields, Hackney, between two butchers of Bishopsgate Street, which, according to the connoisseurs of the pugilistic art, was the choicest ever known. The combatants behaved with uncommon resolution during an hour and ten minutes, when it was ended by the least being carried off the field for dead. The bets ran 5 to 3 in favour of the loser – many knock-down blows were given and received on both sides, and on the close of the contest, neither was able to stand alone.”

Almost 80 years after Rocque’s map, in 1823, Hackney was still a village surrounded by fields, with London Field continuing to be an open area to the west, and still being used to graze sheep on their way to market:

In Rocque’s map of 1746, the land to the west of London Fields is shown with horizontal and vertical dashed lines, rather than the symbols used to indicate normal grass fields. In the above 1823 map, this area is now marked as Grange’s Nursery, a large area of space almost running up to Kingsland Road, with what must have been the owners, and or nursery buildings in the centre of the space.

Another comparison between the 1746 and 1823 maps shows that there had not be that much additional development around London Fields. Some additional building, but mainly along Mare Street.

This would all change in the following decades, with the period from 1840 being one of considerable change, with rows of Victorian housing, industrial buildings and streets being developed between Hackney and Kingsland Road, with London Fields surviving as an area of public open space.

There were many challenges by developers to London Fields, with small bits of the space being taken for housing, and there was also digging for gravel at places across the space.

A campaign by those concerned with preserving London Fields as a public open space helped to make the Metropolitan Commons Act of 1866 reach Parliament and become law, with London Fields becoming the responsibility of the Metropolitan Board of Works.

There were continuing issues with gravel digging and fences encroaching onto the space, but these were always challenged and fences torn down. When the London County Council came into being, London Fields was levelled and seeded with grass, paths were created, and Plane trees planted, with a bandstand being built in the centre of the fields.

Looking towards the south of London Fields from the Flower Sellers:

Looking north along London Fields:

In the above photo, the space looks very empty, however it was busy with people, just not on the grass, which was rather muddy after many days of rain.

The main footpath to the right had a continuous stream of walkers and runners, and to the north, the play areas were full of groups of small children in high-vis jackets being shepherded by nursery school teachers, although the play area to the south was empty:

The above photo shows some of the houses that lined the eastern, Hackney side of London Fields, the first side of the fields to be developed.

As with many open spaces in London, London Fields has seen a number of political meetings. One such was reported in the Hackney and Kingsland Gazette on the 15th of March 1886:

“MEETING OF SOCIALISTS ON LONDON FIELDS – On Saturday afternoon, a mass meeting of the employed and unemployed took place on London Fields, convened under the auspices of the Hackney and Shoreditch Branch of the Social Democratic Federation, to consider what was best to be done to alleviate the distress that now prevails to such a terrible extent in the district. A large crowd , numbering some two thousand persons, gathered round a cart in the centre of the fields, from which speeches were delivered.

A large body of police, some 300 on foot and 50 mounted, were on duty. The mounted men were placed at the entrance of the streets abutting the fields, and the other constables paraded the footpaths in pairs. Most of the shops in the immediate vicinity were closed.

The Chairman referred to the rapid growth of the Mansion House Fund since the Trafalgar Square riots as indicating the re-awakening of the well-to-do classes on the subject of the increasing amount of distress in the country, whereat he was interrupted by cries of ‘No charity’, and ‘We don’t want it’. It was not the relief funds that they wanted, but the right to live and to labour guaranteed by the State. If they had justice they would enjoy the wealth they created.”

Charles Booth’s poverty maps created towards the end of the 19th century, shows the contrasting levels of wealth and poverty around London Fields from the dark blues of “Very poor, casual. Chronic want”, up to the reds of “Middle Class, Well-to-do”, with this later grouping occupying the new terrace houses that had been built in the previous couple of decades:

On the north eastern edge of London Fields, there is a pub – the Pub on the Park:

The Pub on the Park is a survivor of the 19th century buildings surrounding the north east of the park.

On the night of the 21st of September, 1940, the area around London Fields suffered considerable bomb damage, resulting in the post-war demolition of the buildings around the pub, which was restored and survived.

The pub was originally called the Queen Eleanor and renamed to the Pub on the Park in 1992.

The pub seems to date from the mid 19th century development of the area, and the first references I can find to the Queen Eleanor date from the 1850s. There may have been a pub on the site prior to the current building, as a place where people travelling through the area, and grazing their sheep in the fields, would have also attracted businesses such as pubs, although I can find no evidence of the predecessor to the current building, although I suspect it was part of the mid 19th century development.

The sign of the Pub on the Park:

From the photo of the pub, it is clear that it was once a corner pub, and a look at the other side of the pub shows that it was once joined to another house. This side is also now decorated:

The reason for the original name of the pub is clear in the following extract from the 1893 OS revision. The pub is circled and Eleanor Road runs upwards from the left of the pub (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“):

What is remarkable about the above map is that Eleanor Road, and the houses along the left hand side of Tower Street were not rebuilt after the war, and the area was taken into London Fields, grassed over, and is now part of that open space.

The pub is now isolated on the edge of the fields.

Follow Eleanor Road to the north and the road meets Richmond Road. The houses along the southern side of Richmond Road, at the northern end of the park, were also not rebuilt and London Fields now extends to border Richmond Road, with the exception of a small stretch of housing to right and left.

Tower Street in the above map is now Martello Street. It is always interesting to walk the side streets as there is frequently so much to see, for example just before where Martello Street dives under the railway viaduct:

At the north western corner of London Fields is the London Fields Lido:

The Lido was one of many opened across London during the 1920s and 1930s (see here for a bit about the Parliament Hill Lido), although all the news reports from the time refer to it as an open air swimming bath rather than a Lido.

The Lido was opened in 1932, and was advanced for its time, having an advanced filtration plant as well as a water aerator in the form of a fountain. As well as the pool, there was a sunbathing area, first aid room and a refreshment kiosk, and the Lido was designed and built by the London County Council.

The Lido closed for the war, opening in 1951, the same year as the Festival of Britain. I do not know if these events were connected, but the Festival did act as a catalyst for other post war improvements and renovations to public infrastructure and facilities.

The Lido remained open until 1988, after which there were proposals to demolish the Lido and return the area to grass within the overall London Fields grassland, as had happened with the post war demolition of the bomb damaged housing at Eleanor Street..

The London Fields User Group were concerned about the threats to the Lido, and the loss of such a facility, so a sub-committee was established to campaign for the reopening of the Lido.

The condition of the Lido deteriorated rapidly, with the Lido sub-committee arranging work to try and stop too much deterioration, whilst continuing to campaign for restoration and reopening.

Funding and designs were finally available in 2005 when work started, with the Lido reopening in October 2006 for a few months for testing. More work was needed over winter, and the Lido fully reopened for Easter 2007.

The Lido seemed busy on the day of my visit to London Fields, and, despite being a February day there were plenty of swimmers in the open air pool, although having the water at 24 degrees centigrade must help.

From sheep grazing to a Lido, London Fields has been a key part in the development of Hackney for centuries, and continues to be a valuable area of open space surrounded by dense streets of 19th century development, as London engulfed the small villages surrounding the city.