Thanks for the feedback to last week’s post where I had used plaque rather than plague. I think I was being a bit too quick with a spelling check. All hopefully now corrected.

I do not usually cover topical issues in the blog, however today’s post looks at a site which could well have a controversial transformation in the coming years, as well as a bit of the history of the site.

This is the tree hidden view of the old Royal Mint building, looking across East Smithfield:

The 1890s book “The Queen’s London” has a much clearer view of the building. I assume the two trees we see in the following image will grow into the two we see today:

The story of the Royal Mint goes back many centuries, and for much of the time, the Royal Mint in London was based within the Tower of London. A suitably secure place for the minting of the nation’s coinage.

By the end of the 18th century, steam power was taking over many industrial processes, and with the country’s growing international commerce, much of it based around the London Docks, the demand for coinage was growing.

The Tower of London was far too small a site to accommodate the new steam technology that could be used for the manufacture of growing amounts of coinage.

In 1798, King George III appointed a committee of the Privy Council to look into the future of the Royal Mint and the committee decided that a new location and building was required.

The site would, ideally, still be within central London and close to the Tower of London, and also where a sizeable amount of land was available.

One such location was just to the north east of the Tower of London, a site which consisted mainly of a Royal Navy Victualling Yard, along with a number of small side streets, courts, workshops and housing.

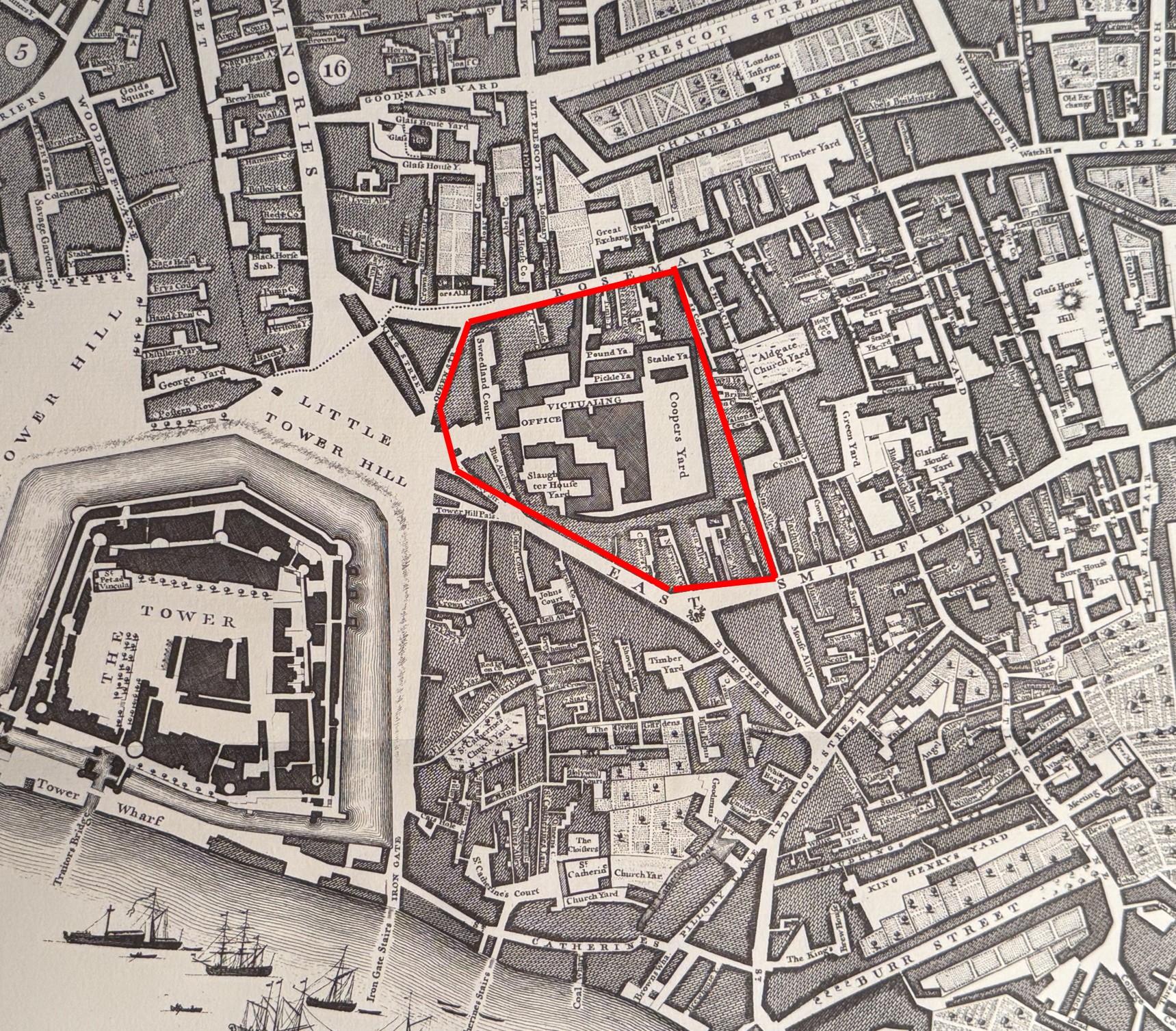

I have marked the area which would become the site of the Royal Mint on the following extract from Rocque’s 1746 map of London, where it can be seen that the Victualling Yard occupied a large amount of the future space of the Royal Mint. The map also shows the size of the future site compared to the Tower of London, the Mint’s original home where only a proportion of the space was available to the Mint:

It took a while to clear the site, plan the new Mint and complete the build, and it was finally complete in 1809, with the Royal Mint moving out of the Tower of London, where it had been since 1279 when a small Mint was first established within the secure walls of the Tower.

The new building was the work of surveyor James Johnson along with his successor Robert Smirke.

The new Royal Mint building, twenty one years after completion, drawn in 1830 © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.):

The main Royal Mint building is Grade II* listed, the white entrance arches and lodge to either side are Grade II listed.

The early 19th century building is the main visible part of the complex (only just visible between the trees), and there is far more to the site as it expanded and adapted to post Royal Mint use over the years.

Looking through the railings, we can get a slightly better view:

I have a bit of a thing about the placement of some trees in London. Whilst I certainly believe that many more trees are needed across the city, there are some where they obscure the original view intended by the architects of a building. The Royal Mint building is a prime example, another is the Royal Festival Hall where the trees on the walkway in front of the building obscure the view of the Royal Festival Hall from across the river (see this post).

The Royal Mint was at Tower Hill until the Mint started to move out of the Tower Hill location in the late 1960s. Production of new decimal coinage along with a growing business producing coinage for other countries required a larger site, and in 1968, Queen Elizabeth II opened the new Royal Mint works at Llantrisant, South Wales, and the last coin was produced at Tower Hill in 1975.

Not everyone was happy to see the Royal Mint leave London, for example an H.J. Arlett of Peckham wrote to the London Evening News on the 1st of September, 1967:

“The business of producing coinage by the Royal Mint has now expanded to such an extent that it is proposed to move to a larger site in Glamorganshire. Why?

Why not keep this Chief Department appropriately enough in our Capital City? Subsidiary departments can always be opened in other areas should the need arise. Why should the defacement of this interesting capital of ours be allowed to continue and prove to the detriment of overseas visitors and our places of interest.

Which of our landmarks will be next, the Bank of England, the Royal Exchange, the Mansion House? How long before the Tower of London becomes another tower of Blackpool.

Let us keep our capital a centre of interest, not just blocks of offices.”

Questions about London’s purpose and future have probably been asked for as long as London has been the Capital City of the country.

Since the Royal Mint left the building, it has had a number of uses, including office space and I remember that a number of tech start-ups were based there in the late 1990s early 2000.

The controversial transformation I alluded to at the start of the post is the future use of the old Royal Mint site, with China planning that the whole site will become their new Embassy complex, having purchased the site in 2018 for £255 million.

The site is a considerable size of 2.10 hectares or over 5 acres. It comprises the original building that faces on to Tower Hill, as well as a complex of 1980s buildings onwards that were built around the site as it was used for office space. There is also the Grade II listed Seaman’s Registry, designed by James Johnson and built in 1805 as staff accommodation for the Royal Mint.

The site also contains some preserved remains of a Cistercian Abbey, the St. Mary of Graces monastery which date from the 14th century (which also illustrates how many religious establishments there once were in London, as just to the south, where St. Katherine Dock is now located, was the St. Katherine Hospital and Church, founded in the 12th century by Matilda, Countess of Boulogne, the wife of King Stephen who reigned from 1135 to 1154).

There is also a 14th century Black Death burial ground, many other archaeological remains as well as remains from the Royal Navy Victualling yard which occupied the site prior to the Royal Mint.

The overall scope of the site is shown in the map below where I have marked the planning application boundaries with the red line. The square indentation along the northern boundary is a BT telephone exchange. When three letter codes were used as part of the telephone number, this exchange was ROY for ROYal, due to the exchange’s location next to the Royal Mint.

The telephone exchange is apparently due to cease all operations in 2033 and to be empty the same year. Its future use will be interesting given the location of the building as being almost part of the proposed Chinese Embassy estate:

To add to the importance of the site, it is within the Tower of London Conservation Area and is also

within the boundary of the Tower of London UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The proposed embassy would not only be the largest embassy complex in the UK, but would also be China’s largest embassy in Europe, as well as being around 20% larger than their embassy in the US.

The proposed plans for the embassy complex include some very limited public access, as well as a small area for historical information and interpretation displays and exhibits.

The planning application has been turned down by Tower Hamlets Council, and the current status is that the application has been called in by the Government and is now under review by Angela Ryaner who oversees planning matters in her role as housing secretary.

The latest from early August is that Angela Raynor has asked the Chinese to explain why parts of the building plans are greyed out and marked “redacted for security reasons”.

The Grade II listed entrance arch and lodge:

There are very valid views on whether the site should be used as an embassy for China, and also why China needs such a large complex for their London embassy, but I also think that the future use of the building shows the lack of ambition (and money) that we have as a country, for the use and redevelopment of such an important site, at a very key location.

The clustering effect of the Tower of London, Tower Bridge, St, Katherine Docks and the old Royal Mint buildings would make the site ideal for redevelopment for cultural / historical use, even with the redevelopment of some of the buildings at the rear of the estate as residential to help fund, it would preserve the listed James Johnson and Robert Smirke building and the Seaman’s Registry for public use.

It would also have been aa brilliant location for the Museum of London (although the Smithfield site is equally good), and perhaps this shows the challenge of a City where too many historic sites such as Smithfield Market, the old Customs House in Lower Thame Street etc. are looking for a future use, and in reality is an embassy so very different to the site being redeveloped with apartment blocks and hotels, which would probably be the alternative.

This was part of the original intention for the site after client funds of two real estate investment companies had purchased the site from the Crown Estate in 2010, and who then received planning permission for new retail and leisure accommodation, 1.8 acres of landscaped public space, and a large amount of high specification office space.

The owners received an unsolicited offer from China in 2018, and it was probably too good an offer to refuse.

View looking along Mansell Street, the north western boundary to the site, with part of the brick Seaman’s Registry building visible along with 1980s additions:

The high brick wall seen in the above photo still surrounds much of the site, and was there to prevent access to a place where large amounts of coinage, gold and silver were being stored and processed.

Despite the walls intended to keep people out, much of the reported theft was by employees, and the following from the London Dailey Chronicle in November 1912 is typical of the small amounts of theft by employees of the Mint:

“THEFT FROM THE ROYAL MINT. A sad story of the downfall of a trusted employee at the Royal Mint was told at the Thames Police court yesterday, when Charles James, aged 55, a foreman packer, was sent for trial on a charge of stealing silver coins to the value of over £36.

James, it was said, had been 29 years at the Mint, and next year would have been entitled to retire on a pension. His salary was £2 a week, with 6s. extra for searching suspected persons.

He was seen by a packer to plunge his hand several times into bags of worn silver coins which were being emptied, and £36 3s 6d was found in his pockets. When accused James said, ‘I must have been mad’. He was stated to have recently been ill, and to have borne an excellent character. Bail was allowed.”

The following photo is along Royal Mint Street, along the northern boundary of the complex, and the tall brick building where the wall ends is the old Telephone Exchange:

The GR cypher on the arms on the building indicate that it was built in the reign of King George V, between 1910 and 1936:

The Royal Mint at Tower Hill was used for many other related purposes, not just for the production of coinage.

Go back to the end of the 18th century, and Britain was a country with a growing trade with the rest of the world. One of the problems with trade was knowing what you were actually buying from a producer in another country. France had only just started to use the metric system at the end of the 18th century, and the rest of the world used a number of different, localised systems.

In 1819, the Government tried to take the lead in establishing the relationship between weights and measures of different countries, and this work was to be done at the Royal Mint on Tower Hill. From the Morning Herald on the 6th of February 1819:

“The commercial world will learn with satisfaction that a plan has been commenced, under the auspices of the British Government, for determining the relative contents of the weights and measures of all trading countries. This important object is to be accomplished by procuring from abroad correct copies of Foreign standards, and comparing them with those of England at his Majesty’s Mint. Such a comparison, which could be effected only at a moment of universal peace, has never been attempted on a plan sufficiently general or systematic; and hence the errors and corrections which abound in Foreign tables of weights and measures, even in works of the highest authority.

In order, therefore to remedy and inconvenience so perplexing in commerce, Viscount Castlereagh, has, by recommendation of the Board of Trade, issued a circular directing all the British Consulates abroad to send home copies of the principal standards used within their respective consulates, verified by the proper authorities, and accompanied by explanatory papers and other documents relative to the subject. The dispatches and packages transmitted are deposited at the Royal Mint, where the standards are to be forthwith compared.”

Looking along East Smithfield, the street that forms the southern boundary to the Royal Mint estate, part of the upper floor of the James Johnson and Robert Smirke building can just be seen:

As well as the metals used for day to day coinage, the Royal Mint was responsible for measuring the quality of, and the production of gold and silver coins.

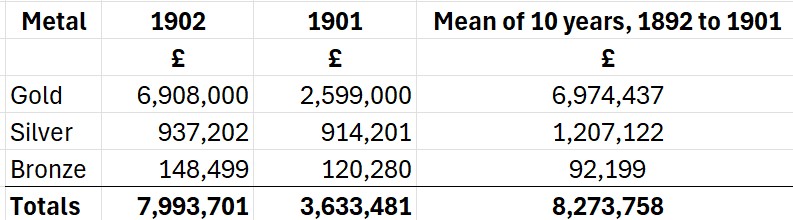

All coinage minted at the Royal Mint was sent to the Bank of England for distribution, and the Royal Mint issued an annual report on the quantity of types of coins and metals that they had produced, as well as coins that had been returned to the Royal Mint as worn or withdrawn. In the 1903 report, the Royal Mint stated that they had produced in the previous two years:

These numbers may not look large by today’s standards, however using the Bank of England inflation calculator, £7,993,701 as the total for 1902, would today be £851,292,858 (although this is not an easy comparison, as the value of different metals such as Gold have changed in a different way to inflation).

The report also includes details of the significant amounts of gold and silver that were being brought into the country as well as being exported.

There were complex rules for those involved with the smelting of precious metals such as Gold at the Royal Mint. These once included not allowing workers out of their work place for the entirety of their shift, and only releasing them to go home when the amount of gold had been checked against that at the start of the shift, with the worker then being issued with a certificate releasing them from their day’s work.

Whilst today Gold coins are not in common usage, they are still produced at the Royal Mint’s south Wales facility, although this is mainly for investment and collecting purposes.

You can today buy a quarter ounce Britannia Gold bullion coin (999.9 fine gold) for £680. The Royal Mint also produces Gold bullion bars, however if you sell, these are subject to Capital Gains Tax, whilst Gold Bullion coins are exempt from CGT due to their classification as legal British currency, although the £680 Britannia Gold bullion coin has a denomination of £25, so I doubt you will get one of these in your change, the value today being aligned with the metal of the coin rather than the denomination.

The view looking east along East Smithfield, the tall building on the left of the street is part of the Royal Mint estate, and is planned to be demolished, and replaced by a new building that runs along the eastern side of the estate:

Although a large site, the growth of the Royal Mint has raised questions about the location over many years. In 1881 there was the possibility of moving to a site on the Thames embankment, which had been completed in the previous decades. This proposal was turned down by the Select Committee on the London City Lands Bill who determined that the existing site and buildings were more than sufficient for the demands likely to made on the Royal Mint, with a few alterations made to the existing buildings.

To the east of the Royal Mint is the appropriately named Royal Mint Estate:

There are concerns about the impact of the embassy development on the Royal Mint estate, privacy, security, the potential impact of any demonstrations against the embassy etc.

In the above estate plan, Cartwright Street is the street along the right hand edge. There is a narrow row of flats along the right of this street, and then the existing buildings of the Royal Mint estate loom large, buildings that will be replaced by those of the Chinese Embassy.

The Royal Mint tells us a number of stories.

The move to south Wales after several hundreds of years in London was about the need for more space and the city being less of an attractive site for industrial processes. There was probably also a financial factor with the new site being cheaper, and less expensive than an update to the London site.

The Royal Mint continues to operate in south Wales, however the centuries of growth is now probably followed by decline with the growing reduction in the use of cash, and today the Royal Mint is now building on the demand for gold, a metal whose price has risen considerably over the last few years.

The future story of the Royal Mint, Tower Hill site also tells the story of changing global politics, the rise of China, and the decisions that the Government makes on the future of the site will show how we respond to changing global politics and how we make use of key, landmark historical sites in the city.

It will be interesting to see the decision making in the coming months and the eventual outcome for this historic site.