I had intended to be away from London just for the month of August, however I had the opportunity for a trip to Edinburgh so I hope you do not mind if I cover one more location before returning to London for next week’s post. This will be in two posts, today covering the City of Edinburgh and mid-week a post on the Forth Bridge.

Edinburgh is a wonderful city. Although geographically and from a population perspective Edinburgh is much smaller than London, they share a number of features. A long and fascinating history, a capital city, a seat of government and today a major tourist location.

Edinburgh was also the home to many of the people who helped to shape the modern world during the 18th century including the philosopher and historian David Hume. Adam Smith, the author of the Wealth of Nations, the first modern book on economics.

James Boswell who was born in Edinburgh and went to the universities in Edinburgh and Glasgow before his move to London. James Hutton the Geologist who recognised that the Earth was continually developing and forming and that erosion and sedimentation can help to understand how these continuous processes have worked over geologic time (which is not surprising given the amount of geology surrounding Edinburgh, all the inspiration needed to get out and explore).

Henry Home, Lord Kames, a Scottish Advocate who developed theories on how human societies developed and how the need for laws developed alongside society, for example that at the highest stage of development, law was required for the protection of property.

Edinburgh’s role in the Scottish Enlightenment is a fascinating subject.

Back to the main subject of today’s post, my father photographed Edinburgh in 1953, so here is a sample of these photos along with my photos taken 63 years later.

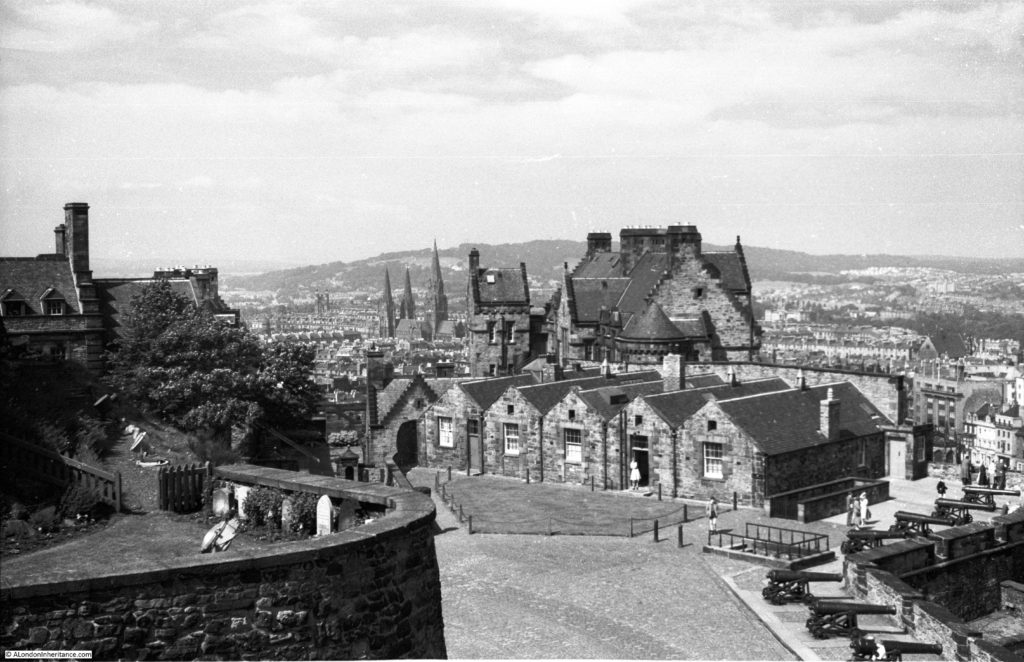

Firstly, a visit to Edinburgh Castle, on the top of Castle Rock, the remains of the volcanic activity across this part Scotland around 350 million years ago.

The earliest part of the castle, St. Margaret’s Chapel, dates from around 1130 when it was built by the Scottish King David I and dedicated to his mother Queen Margaret who as a member of the Anglo-Saxon royal families, fled to Scotland soon after the Norman invasion where she married Malcolm III of Scotland thereby becoming a Scottish Queen.

In the centuries since, Edinburgh Castle has been fought over by the Scots and the English, taken by Oliver Cromwell during the Civil War attacked during the Jacobite rebellions and used as a prison during the Napoleonic wars.

Today, Edinburgh Castle is home to the Scottish Crown Jewels, the Stone of Destiny (which was in Westminster Abbey after being taken from Scotland in 1296 by Edward 1, but returned to Scotland in 1996 and will now only be returned to London for coronations), the Royal Palace, the Scottish National War Memorial and a number of Regimental Museums.

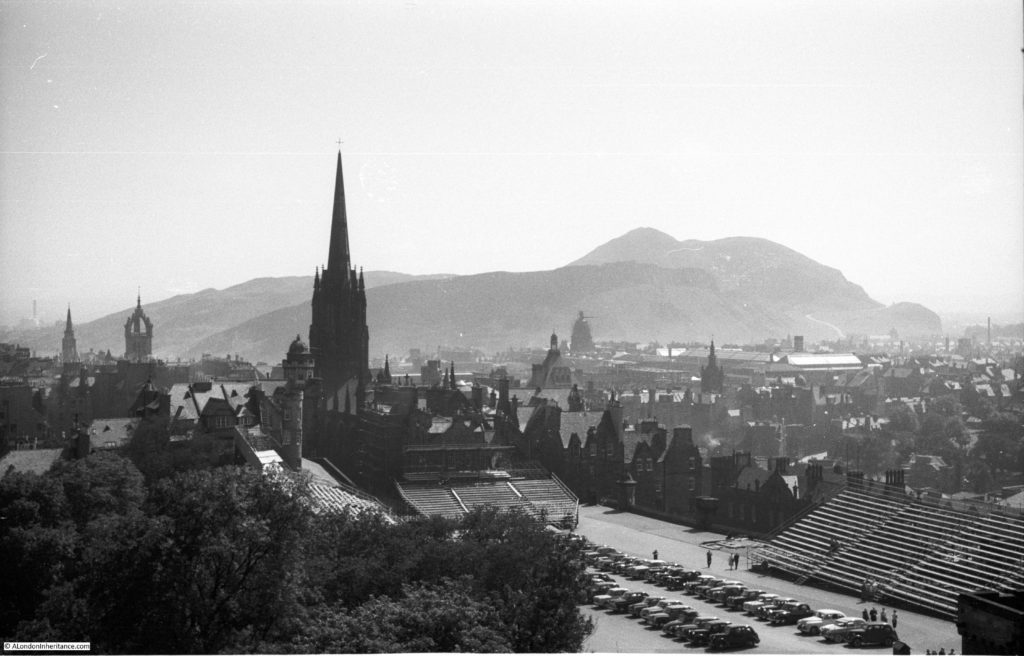

Edinburgh Castle also provides some superb views across Edinburgh to the Firth of Forth and it is here that I start with the following photos. I could not get to the exact location where my father had taken these photos in 1953. I could see the location, a small walkway around the top of one of the rooms adjacent to the Lang Stairs, but it is now closed off. Frustrating but understandable given the number of visitors to the castle today,

I will work my way from the view to the north-west, moving gradually over to the east.

To the left of the above photo is the Solders Dog Cemetery where the pets of solders and regimental mascots are buried. In my photo below the outer wall can just be seen to the left of the photo.

The castle is, as you would expect, much the same as 63 years ago with only minor changes. The main difference is the number of visitors to the castle with 1.568 million visitors in 2015 (to put this into perspective, in London St. Paul’s Cathedral had 1.609 and Westminster Abbey with 1.664 million visitors so Edinburgh Castle is almost as busy as these two main London hubs for visitors).

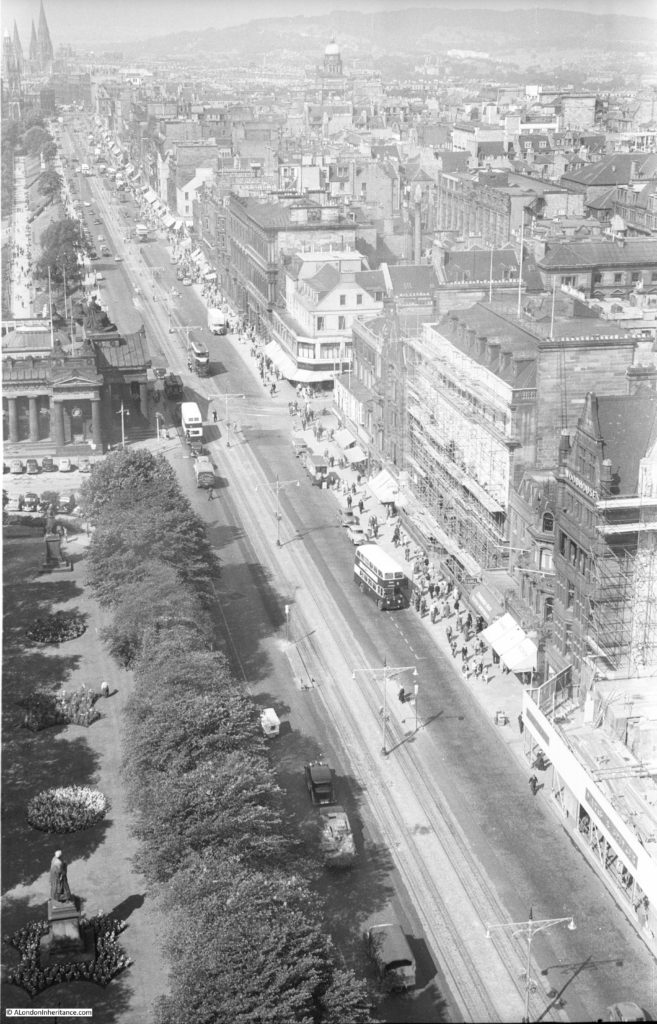

Starting to move to the east and the “New Town” of Edinburgh is starting to come into view with the Firth of Forth in the distance. The New Town was built between the mid 18th and 19th centuries as a result of the growing population of the city and the lack of space in the original Old Town. Princes Street is the wide street running left to right.

Standing along the edge of the castle and looking out across the city, it is remarkable how the views are much the same. Parkland separates Castle Rock from the rest of the city, Princes Street still provides a wide roadway, the New Town and the later suburbs of Edinburgh stretch away towards Muirhouse, Trinity, Newhaven and Leith.

The height of the buildings have not really changed and unlike London there are no glass and steel towers.

Still moving east and the road running north from Princes Street is Frederick Street.

The 1828 tower of the church of St. Stephen’s Stockbridge can be seen in the centre left of the above photo and more towards the upper left in my photo below.

The church is built from Craigleith stone. Craigleith was a quarry a couple of miles outside of Edinburgh that produced high quality stone. A connection with London is that although Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square is of granite, the statue of Nelson on the top is carved from three blocks of Craigleith sandstone.

Further to the east. In the photos above and below the Melville Monument in St. Andrew’s Square can be seen at the right of both photos. The 1st Viscount Melville, or Henry Dundas was a Scottish Advocate (lawyer / solicitor) who dominated Scottish politics in the later years of the 18th century and first decade of the 19th century.

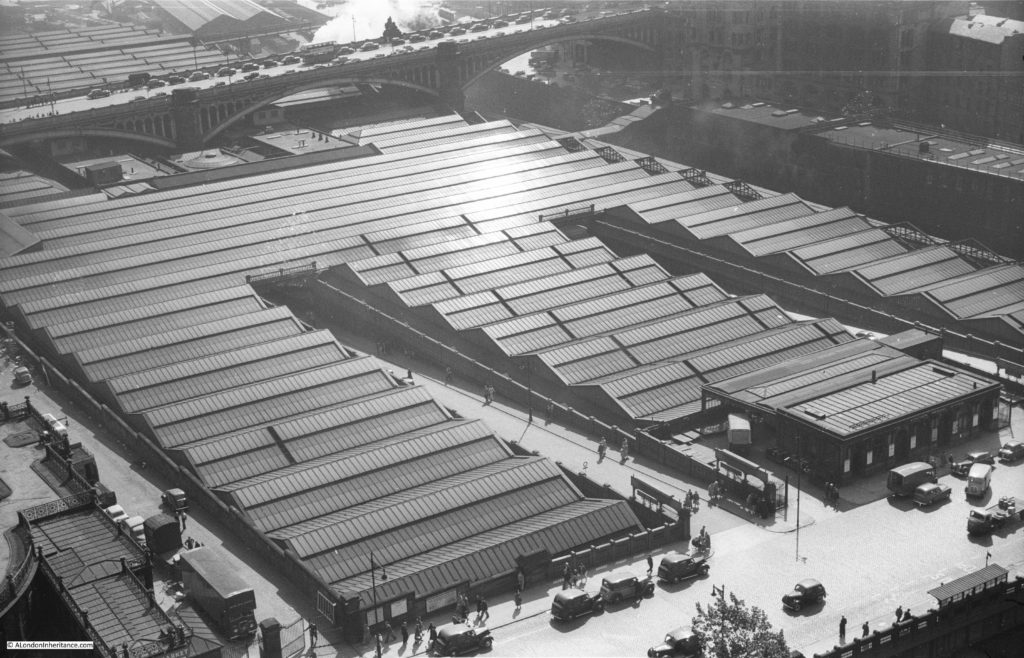

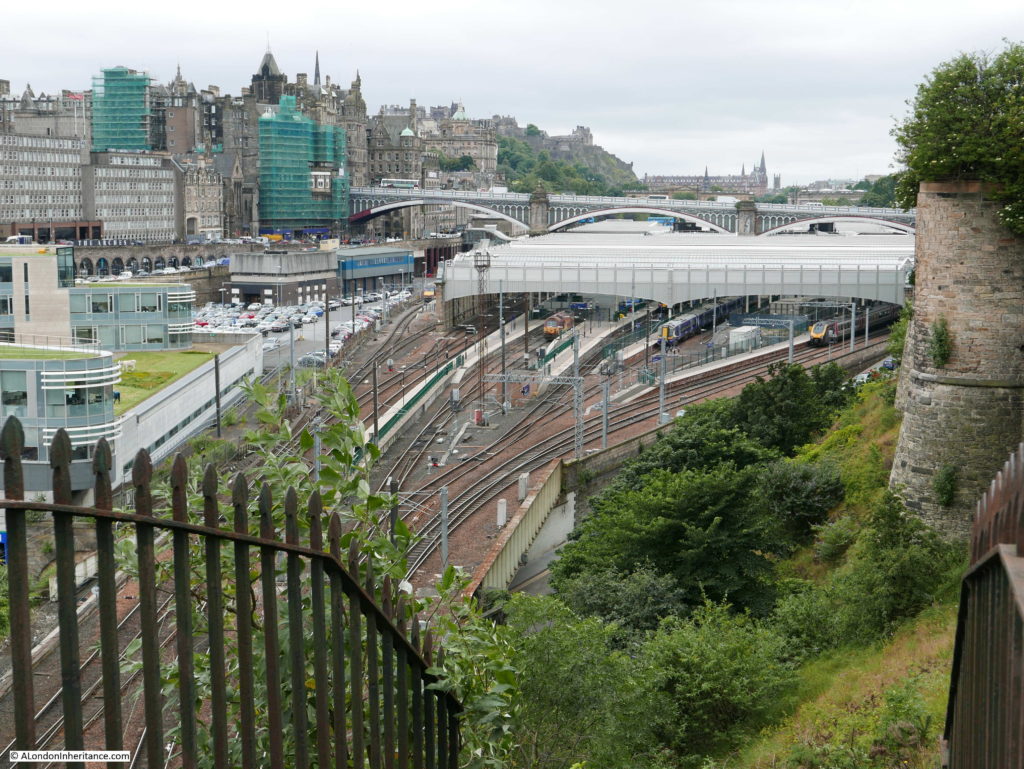

Moving further towards the east, the entrance tunnels to Edinburgh Waverley Station can be seen with the station on the right. The Scottish National Gallery is above the tunnels with the Scott Monument behind the Gallery.

Edinburgh Waverley Station is in the centre of the above and below photos with Calton Hill in the background with the tower of the Nelson Monument and the columns of the Scottish National Monument just behind. Waverley Station was built in the natural valley between the old and new towns. Originally opened in 1846 and rebuilt between 1892 and 1902 when the station became substantially the station we see today.

As we continue looking further east, the original old town of Edinburgh comes into view with the tall tower of the original Victoria Hall, built to house the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland between 1842 and 1845. The building was never consecrated as a church. It is now a centre for the Edinburgh International Festival as well as providing space to hire throughout the year – a strange history for a building that appears on the skyline to be the central church for the city. The main church for the old town of Edinburgh are the towers further back with first the tower of St. Giles Cathedral. The tower behind this is the Tron Kirk. Although no longer a functioning church (mainly now market and retail space), the Tron Kirk has a long history with the original foundations being laid in the 1640s.

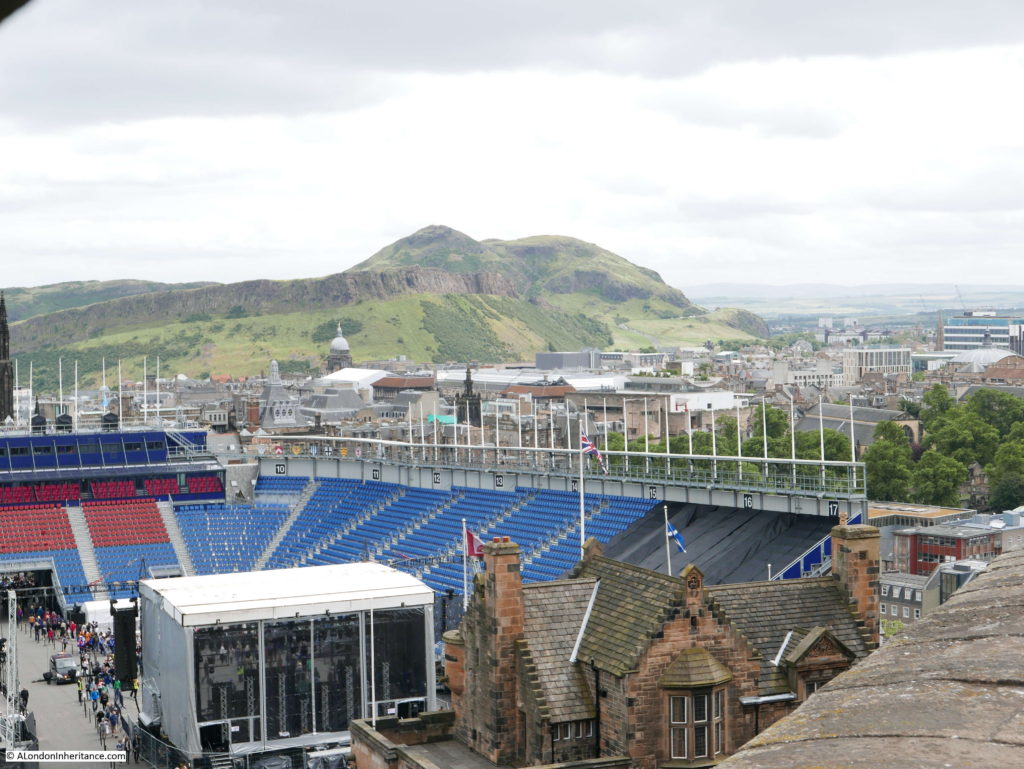

As the photos above and below have been moving to the east, the entrance to the castle has come into view and in both the 1953 and 2016 photos the seating and preparations for the Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo can be seen.

The first tattoo was in 1950, so just a few years before my father took the above photos. Although the basic concept is the same, the Tattoo is now a much more sophisticated presentation and the seating is also on a much more grander scale, able to seat an annual audience of 220,000 for three weeks in August. The Tattoo is consistently sold out and apparently in the history of the Tattoo not a single show has been cancelled which is quite an achievement given Scottish weather and the high, exposed position of the Tattoo.

In the above photo, the queue to buy tickets for the castle is in the lower centre – the castle is a highly successful attraction for the City of Edinburgh.

The next stop is the Scott Monument on Princes Street.

Sir Walter Scott was a highly successful Edinburgh based novelist. His books included Rob Roy and Ivanhoe and his series of “Waverley” novels gave him considerable fame. He also discovered the Scottish Crown Jewels after they had been lost in Edinburgh Castle where they had been stored away in a box which had been unopened for many years.

The Scott Monument has a series of viewing galleries and provides superb views of the castle, Princes Street and Waverley Station. A few facts about the monument:

- the foundation stone was laid in 1840

- the monument was completed 4 years later in the Autumn of 1844

- the total cost of the monument was £16,154, 7s, 11d

- the height to the very top of the monument is 200 feet, 6 inches (or 61.1m)

A competition was held for the design of the monument and George Meikle Kemp, a carpenter and draughtsman won the competition with his Gothic style for the monument, beating several leading architects. Kemp supervised much of the building of the monument, but drowned in March 1844, shortly before completion and it fell to his brother-in-law Thomas Bonnar to complete the Scott Monument.

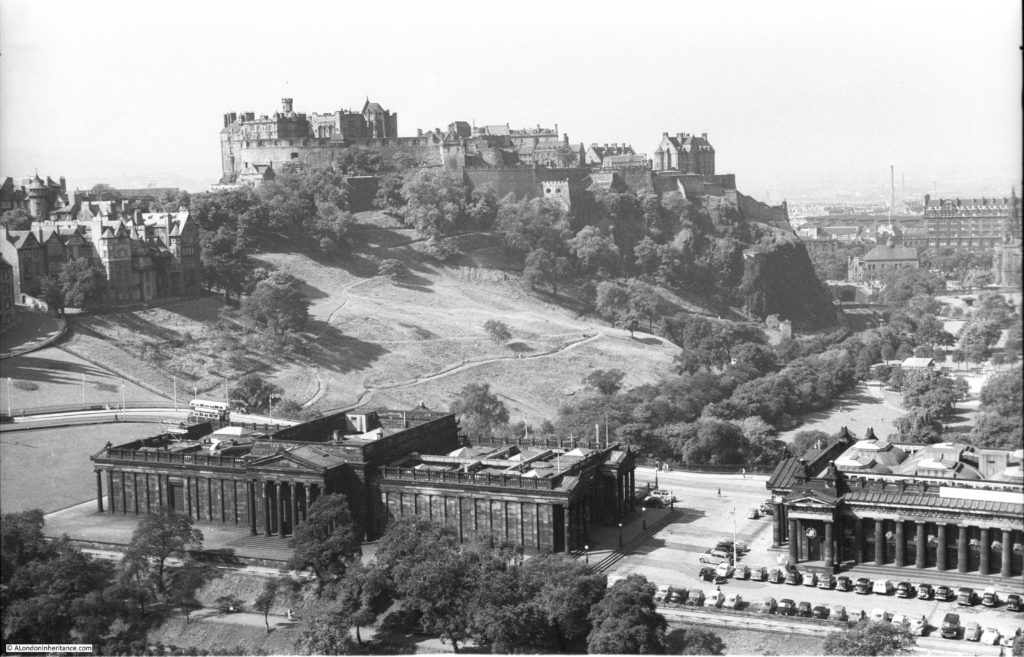

Climbing the monument provides some superb views.

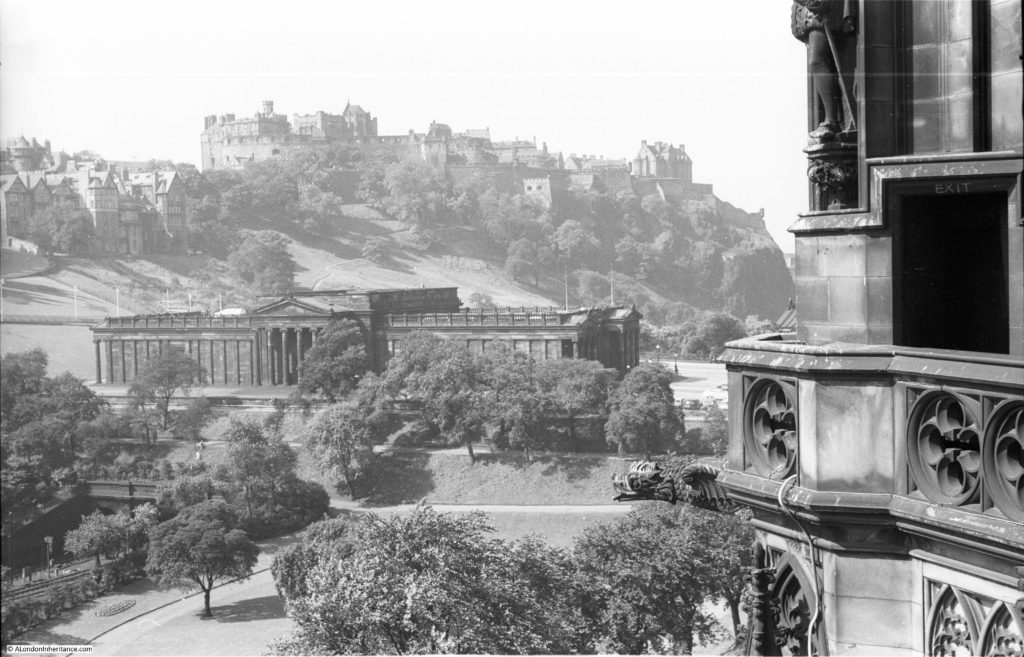

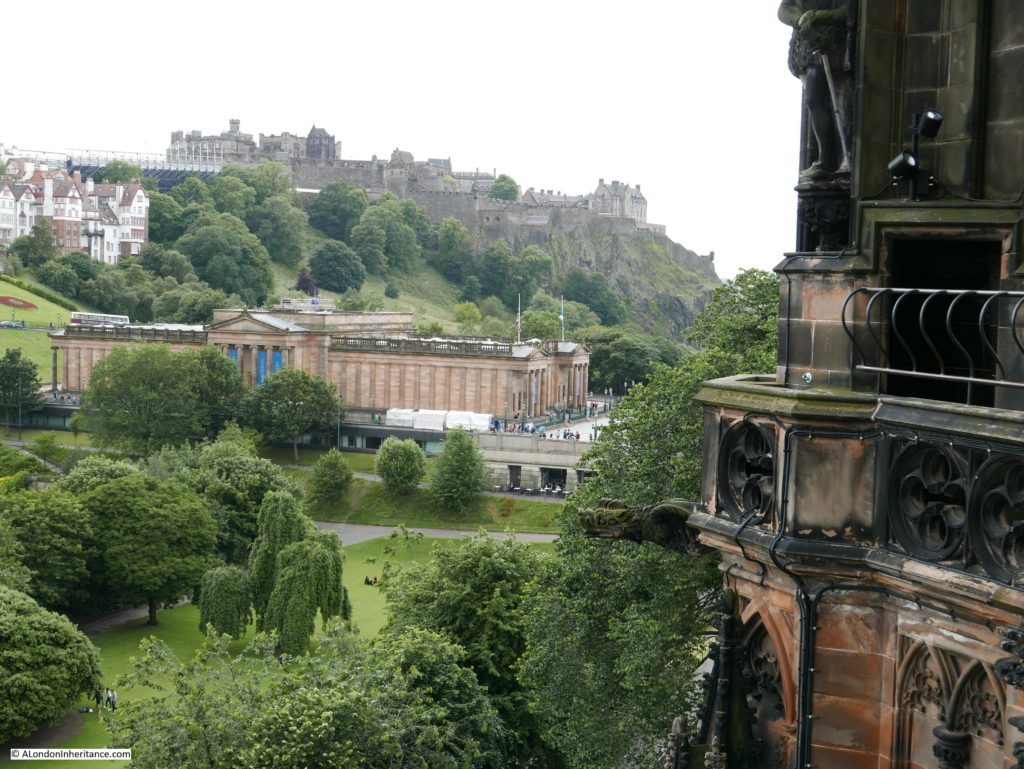

The Scottish National Gallery to the lower left with Edinburgh Castle behind.

I was pleased with this pair of photos as I was able to get the view almost exactly aligned with the photo my father took in 1953. Note in the 2016 photo below that railings have been installed on top of the wall that surrounds the walkway around the monument. The wall is not that high so the railings provide an additional sense of security as you walk around the monument.

Above and below photos of Waverley Station with the North Bridge in the background that links the Old Town with Princes Street and the New Town.

View looking down the length of Princes Street.

And another pair of views along Princes Street.

Leaving the Scott Monument, and in the following two photos is Canongate Kirk. The Kirk is on the Royal Mile, however the following two photos were taken from Regent Road, which runs around the edge of Calton Hill. The photos show the rear of the Kirk and the Kirkyard. The original building was completed in 1690, however the interior has been through many subsequent changes, including the refurbishment needed after a major fire in 1863.

The Kirkyard is the final resting place to many Scots from the 18th and 19th centuries including the Political Economist Adam Smith, the author of the Wealth of Nations.

The same view today. Whilst the buildings around the Kirk have changed, the Kirk and Kirkyard have hardly changed in the 63 years between the two photos.

I cannot place the location of the following photo, however on the strip of negatives it is adjacent to the photos of the Canongate Kirk and is also looking down onto a cluster of buildings, so I suspect it was also taken from Regent Road and must be to either the left or right of the Canongate Kirk, looking down to typical Edinburgh Old Town housing.

As mentioned earlier in this post, the New Town was constructed due to the rising population and the lack of space in the Old Town. In trying to accommodate a growing population, 18th century buildings had risen to seven or eight storeys, some of the earliest “high rise” buildings in Europe. These are the buildings in the background of the photo below. This is the rear of these buildings with the front facing onto the Royal Mile.

The 1953 photo also demonstrates the origin of one of the nicknames for Edinburgh – “Auld Reekie” – meaning Old Smokie as the numerous coal fires of a dense population would send lots of smoke into the air and obscuring the view of parts of the city from a distance.

Also from the same road is the following photo showing the opposite site of Waverley Station with the North Bridge in the background.

No steam trains on these lines now!

Returning to the Canongate Kirk, the following photo is from within the Kirkyard looking up towards the circular Dugald Stewart building on Calton Hill.

I should do more research before visiting as we passed the Canongate Kirk and walked further down the Royal Mile to the large graveyard between Calton Road and Regent Road, thinking this could be where the above photo was taken from – I was wrong, although this graveyard provided a fascinating glimpse of Scottish graveyards.

The majority of graves seem to be from the early to late 19th century. The tower at top right was occupied when the graveyard was in use. A plaque on the side of the tower reads:

“In Loving memory Of John McDonald. Born at this Watch Tower 1.12.1912 died Australia 26.1.1995”

What a place to have been born.

The grave of Andrew Skene. The inscription reads “Misfortune soothed by Wisdom” and records that Andrew Skene was born on the 26th February 1785 and died on the 2nd April 1835. He was an Advocate and Solicitor General for Scotland..

Edinburgh is a fascinating city to walk. It is not just the obvious high spots such as the castle, Scott Monument and Calton Hill, but the streets and alleys where the history of the city is to be found at almost every turn. Old signs still record previous businesses that operated along the side streets.

And the names and faded signs record the importance of the role of Advocate or Solicitor in the development of Scotland as a country which, although part of the United Kingdom, retains a different legal system.

Edinburgh is a fascinating city, wonderful to explore on foot and with a long and complex history. From an architectural perspective, Edinburgh has developed in a different way from London over the last six decades. The skyline is much the same and the city appears to have avoided the high-rise glass and steel developments that are taking over much of London allowing the city to retain a very distinctive feel.

One final post in the next couple of days will look at the Forth Bridge, then back to London for a trip to Wapping High Street.