Although by far the majority of my father’s photos are of London, he took his camera with him where ever he went, and in the late 1940s and early 1950s, along with some friends, he cycled across the UK, staying in Youth Hostels and taking photos along the way. I have already featured a number of these locations.

In 1952 he also traveled out to the Netherlands, cycling to a number of cities, both typical tourist destinations and also places that had featured significantly in the war. (I will use the Netherlands as the full name of the country, probably better known as Holland, although this is really only the name of the western province of the country).

Coincidences are strange. My father always wanted to return to the Netherlands and in 1989 my job transferred to the country, so along with my wife and daughter I moved out to live in the Hague for the next five years. It was a wonderful experience, and during this time my parents came to visit several times and we took them to visit the places my father had been to almost forty year earlier.

I knew that he had taken photos, but these photos had not been printed so it has been only in the last few years that I have scanned and seen the photos he took during his post war visit – I had not seen any of these when we lived in the country.

We recently decided to spend a week in the Netherlands this summer to visit the places where we use to live, and as my aim with this blog is to trace the locations of my father’s photos it was a perfect opportunity to track these down as well, now that they have been scanned, rather than hidden in negative boxes.

So, with apologies that this is not London, for the next few weeks I would like to take you on a journey across the Netherlands. Not just tracking down the locations of my father’s photos, but also to discover much about the history of the country, how a suburb of the Hague will forever have a tragic link with west London, how the Dutch commemorate the sacrifices of British and Polish forces, when the war came to Nijmegen, Arnhem and Oosterbeek, and how the bombing of Rotterdam during the German invasion of the country gave an indication of the destruction that would soon visit London.

On the way there are some fascinating individual stories, street photography, some wonderful architecture and architects, and for me, given the state of the world today, some very important lessons that should not be forgotten.

But before leaving, there was some important documentation to check. My father had just bought a new Leica camera from R.G. Lewis in High Holborn and the photographic press at the time was reporting on a number of confiscations of “expensive miniatures” by customs on return to the country. Leica cameras in the post war years could be purchased in Germany for much less than you would pay in the UK so documentary proof was needed that a camera had been purchased in the country. R.G. Lewis were able to provide assurance that the receipt provided sufficient documentation:

With the right documentation to avoid any customs problems on return to the UK, it was time to get going.

From Tilbury to Rotterdam

To start, we need to get from London to the Netherlands. At the time, the easiest method was to take the train out to Tilbury, then catch the Batavier Line ship, Batavier II from Tilbury to the port of Rotterdam.

This is the route that my father took, when, along with two friends, they took their bikes with them from London. They traveled light, each with a bike and a saddlebag containing everything they needed for the trip.

The following photo from Britain from Above shows the passenger terminal building at Tilbury with the station platforms behind the terminal building. The much larger RMS Strathaird is docked rather than the smaller Batavier II.

I would have loved to have seen some photos of the Tilbury terminal, the ship and the outbound voyage, however one of the limitations in the days of film cameras was the cost of film and the amount that could carried, so there are only a few photos.

The first is of the Red Sands fort in the Thames estuary. Built during the war as an anti-aircraft gun emplacement to defend London from aircraft approaching up the Thames, when my father took the following photo of the fort, it was still in use.

In 2015 I was on the paddle steamer Waverley on a trip from central London out to the forts and took the following photo with the Shivering Sands fort and the Red sands fort in the distance.

There are also a couple of grainy and distant photos of the Thames river bank as the Batavier II headed out into the north sea, but the first detailed photos are the arrival at the port of Rotterdam. This one from the bow of the Batavier II:

The Batavier Line was a Dutch shipping line established in 1830 by the Netherlands Steamship Company, when a regular service was operated from the Port of London to Rotterdam. In 1895 the Batavier Line was sold to Wm. H. Müller and Co, and the Batavier name was retained and a number of new ships were ordered including the Batavier II (a replacement of a ship with the same name). The ship was delivered in 1921.

The Batavier II was the only ship of the Bataview Line that survived the war. Of the immediate pre-war Batavier ships, the Batavier V was seized by the invading German forces, but sunk by the Royal Navy in 1941. The Batavier III had also been seized and sunk off Norway in 1942 after hitting a mine whilst being used as a German troop carrier.

Only the Batavier II survived the war to reenter service on the Tilbury to Rotterdam route which survived until 1958 when Batavier ended their passenger services.

The following postcard shows the Batavier II. On the reverse of the card is written “Batavier Line, London to Rotterdam”. The above photo was taken from the front of the boat, just by the railings which can be seen in the postcard.

The port of Rotterdam is one of Europe’s largest ports, as it was when these photos were taken with industries related to shipping lining the river for a considerable distance.

There are no passenger services from London to Rotterdam today, however the alternative would be a train journey from Liverpool Street to Harwich and then the ferry service from Harwich to the Hook of Holland.

I am not sure where the ship docked in Rotterdam. It was not at the Hook of Holland as this terminal is located at the entrance to the port. My father’s photos show that the ship traveled further into central Rotterdam.

When we travelled to the Netherlands this year we did not take the ferry, instead we travelled on the EuroTunnel shuttle service from Folkestone to Calais, then a drive up through France and Belgium, to arrive in Holland.

I suspect my father visited Rotterdam first, and this city will be the subject of one of the coming posts, For this Sunday’s post, it is a brief visit to:

The Hague

Amsterdam is the capital of the Netherlands whilst the Hague is the administrative centre. The city where the States General of the Netherlands (the country’s parliament) is located, along with the Supreme Court and the International Court of Justice.

As with the country as a whole, the Hague has a complex history. The origins of the city date back to the early 13th century, when Floris IV, the Count of Holland established a base in the area,

The city and what was to become the Netherlands has been through a series of occupations, consolidation and separation. The Spanish occupied the city during the eighty years war, the country was a client state of the First French Empire at the start of the 19th century, the country was combined with Belgium with separation only achieved in 1830, and the country was occupied by Germany during the second world war. As with the rest of the Netherlands, the Hague suffered terribly during the last war.

The country has also had a long trading history, at times in competition and also at war with England.

Whilst in the Hague, my father took some photos of the Binnenhof, the meeting place of the States General (the equivalent of London’s Palace of Westminster) and the official residence of the Prime Minister of the Netherlands.

Considering the function of the Binnenhof, access is open and the visitor is free to walk around. Whilst there are armed police around the site, there are no searches or restrictions to exploring the open areas and taking photos.

The main entrance into the Binnenhof complex:

Once inside and standing in the central courtyard, I found the location of the first of my father’s photos:

As probably to be expected of the seat of Government, there has been hardly any change. The main physical change is that the fountain in the above photo has been moved slightly to the left, so just outside of the photo of the same scene today.

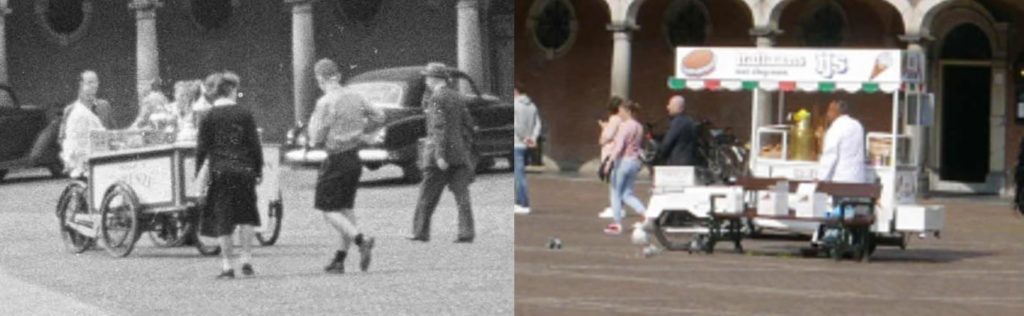

I always find the small details fascinating in comparing the original photos with the scene today. Despite being almost 70 years apart, there is a mobile ice cream seller in almost exactly the same place:

One side of the courtyard is taken up by the Ridderzaal, or Knight’s Hall.

The origins of the Ridderzaal date back to the 13th century when Floris V built his first manorial hall within the area of land first developed by his grandfather. The Ridderzaal has been used for a multitude of purposes over the centuries, and today hosts the annual opening of the Dutch Parliament by King Willem-Alexander.

The Ridderzaal today, again with hardly a change:

I am not sure of the significance of the clothes that this group were wearing.

But again,. the scene is much the same today:

The Binnenhof appears to have escaped any significant damage during the war, although this was not the same for the rest of the Hague. The population suffered considerably during occupation, and the Hague, along with much of western Holland was occupied until the closing months of the war. Supplies were cut and much of the population were close to starving. When I lived in the Hague, work colleagues told stories of the time which included tinned food being floated down the canals from liberated areas into the occupied.

There was also physical destruction to the Hague, not just from the occupation forces, but also from the Allied forces. The suburbs of the Hague were used for V2 rocket launches against Antwerp and London and the RAF tried to address this threat by bombing the facilities used to store the rocket fuel, the rockets and the mobile launch platforms, however one significant bombing raid missed the target resulting in hundreds of deaths among the local population.

In the Binnenhof courtyard is a rather impressive, neo-gothic fountain. Designed by the architect P.J.H Cuypers (who was also responsible for the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam), the fountain was in operation by 1885.

The fountain today. Colour photography brings out the gilding of the fountain. It appears to have been relocated slightly at some point over the last 70 years.

As the home of the Dutch Parliament, the Binnenhof has always had a symbolic importance to the Dutch population and the state. It was therefore used for rallies and ceremonies by the occupying forces not that many years before my father’s 1952 photos. The following photo is of the main courtyard with the fountain visible in the top left.

And in front of the Ridderzaal:

As mentioned earlier, the Dutch population suffered terribly during the war. Arthur Seyss-Inquart was the Reichskommissar of the Netherlands during the war. An Austrian and a fervent Nazi, he aggressively pursued the round up and deportation of Jews within the country. He was found guilty in the Nuremberg Trials and hanged shortly after.

A very different ceremony was held in the Binnenhof courtyard in May 1945 following the liberation of the Netherlands by British and Canadian armed forces.

Directly outside the Binnenhof is the Hofvijver, translated as Court Pond, although the word pond does not seem appropriate for this large expanse of water.

The history of the Hofvijver can be traced back to the first manorial buildings here in the 13th century. It was originally a lake within the sandy landscape of the area (water is never far away in much of the Netherlands).

As part of the development of the Hofvijver, it was bounded by street and pedestrian areas on three sides with the Binnenhof on the fourth side to form a rectangular area of water, which from the sides looks remarkably shallow.

The scene has not really changed for centuries. This painting from the Dutch School, dated 1625 shows a similar view, although the Hofvijver today is not used for any form of boating.

So if it looks much the same over almost 400 years, I would expect the views over the last 70 years to be much the same, and indeed they are:

Apart from the expansion of high rise buildings in the background. The building on the left of both photos is the Mauritshuis, the home to a large collection from the golden age of Dutch art, and home to Vermeer’s “Girl with a Pearl Earring” – well worth a visit.

The small, circular building to the right of the Mauritshuis is known as the “Little Tower” and is the office of the Dutch Prime Minister.

Another view along the Hofvijver:

Although the lake that formed the Hofvijver dates from before the first buildings, the island in the middle is only about 300 years and of unknown original purpose.

A close up view, with the Prime Minister’s office on the left:

At the opposite end of the Hofvijver was a fountain:

And a rather less impressive fountain can still be seen today:

It is interesting to compare transport systems when visiting other cities and whilst the Hague is many times smaller than London, it does have a very impressive public transport system with a combination of buses and trams providing comprehensive coverage of the central city and surrounding suburbs and towns.

Trams navigate the central streets of the Hague and the pedestrian needs to keep a careful lookout for the large number of bikes as well as trams.

I was please to see the number 1 tram. This tram runs from the coastal suburb of Schvenenigen to the town of Delft. It was the tram I caught every day to and from work. The same model of tram is currently in use so these must be over 30 years old.

However very new trams have been introduced on a number of routes.

The public transport system is fast, efficient and reliable. A day card allowing travel on trams and buses across the Hague and the surrounding towns covered by the system costs the equivalent of £6 (and would be less, but given the current very depressed state of the Pound against the Euro),

My father only took a few photos of the Hague, he would take many more in the places he visited next. We left the Hague to Amsterdam as our next destination, but not before a trip to a suburb of the Hague which has a tragic connection with west London and that will be the subject of my next (midweek) post.