For this week’s post I am in Cloth Fair, a street just off West Smithfield with a name that goes back to the early days of the Bartholomew Fair held here when the fair was a centre for cloth merchants from across the country.

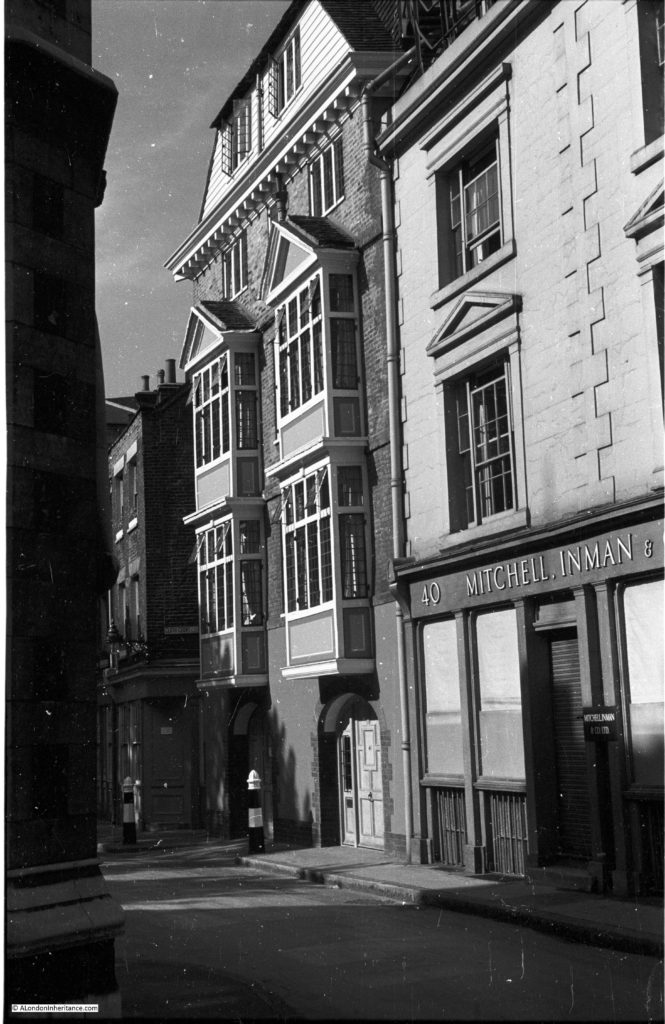

The street name and buildings indicate that when walking down this street we are following in the footsteps of those who have walked Cloth Fair for centuries, but all is not quiet what it seems along the street as I will show later in the post, but for now, it was tracking down the location of one of my father’s photos that took me to Cloth Fair, and to these buildings which he photographed in 1951:

The focus of my father’s photo was the taller of the buildings with the bay windows. These are numbers 41 and 42 Cloth Fair, the oldest residential buildings within the current boundaries of the City of London.

Construction of these buildings started at the end of the 16th century with completion early in the 17th, at a time when the area was within the walled compound of St. Bartholomew’s. They survived the Great Fire of London, and as my father’s photo confirms, they also survived the blitz.

The building on the right, number 40 was occupied by Mitchell, Inman & Co. a wholesale firm in the cloth trade, so even when my father took the photo in 1951 there was still a business specialising in the product after which the street was named. Mitchell, Inman & Co. produced a wide range of cloth based products, and in the London Evening Standard in 1866 they were advertising as “The cheapest house in London for Billiard, Bagatelle, and Card Table cloths.”

My father’s photo was taken from up against the church where, typically for photographing London today, there was building work underway, so my photo is from further along Cloth Fair, but shows the buildings are much the same today.

Ian Nairn described the houses as wonderful – “Wonderful not as a specimen of rustic late-seventeenth century architecture, not even as a very pretty building (which it is), but as an embodiment of the old London spirit. Chunky, cantankerous, breaking out all over in oriels and roof lights, unconcerned with academies, fashions or anything else other than shapes to live in. There was a lot of this in London after the fire; this is now almost the only example left.”

The buildings were almost lost early in the 20th century when they were classified as dangerous structures. The architects Paul Paget and John Seely bought the buildings in 1930 and carried out a very sympathetic restoration. They continued living and working together in number 41 and their success enabled them to purchase and restore many other buildings in Cloth Fair.

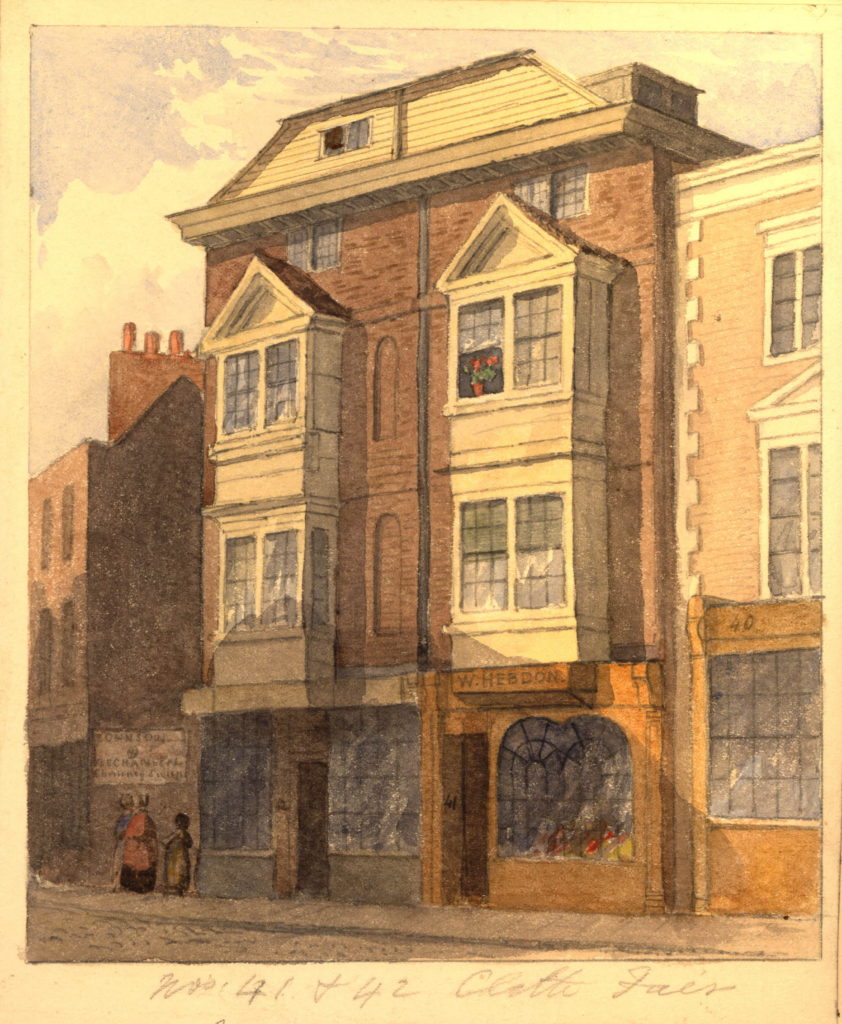

The following print shows 41 and 42 Cloth Fair in 1851 with shops occupying the ground floor of the building:

By 1930, 41 and 42 Cloth Fair had already survived other major changes in Cloth Fair. Up until the start of the 20th century Cloth Fair and the surrounding area included numerous crowded alleys with very unsanitary conditions. The Corporation of London Sanitary Committee condemned many of the buildings in 1914 and their demolition was completed soon after.

The state of Cloth Fair was frequently mentioned in newspapers. Cloth Fair and the Hand and Shears pub were part of the opening and administration of the Bartholomew Fair and the opening of the 1829 fair is recorded in the London Courier and Evening Gazette with “the usual formalities as they are ostentatiously styled, do not go beyond some such ceremony as that of the Lord Mayor and Sheriffs standing in a filthy lane, called Cloth Fair, whilst a Marshalman or Herald miserably reads a proclamation, enjoining such as frequent the fair to abstain from all proprieties.”

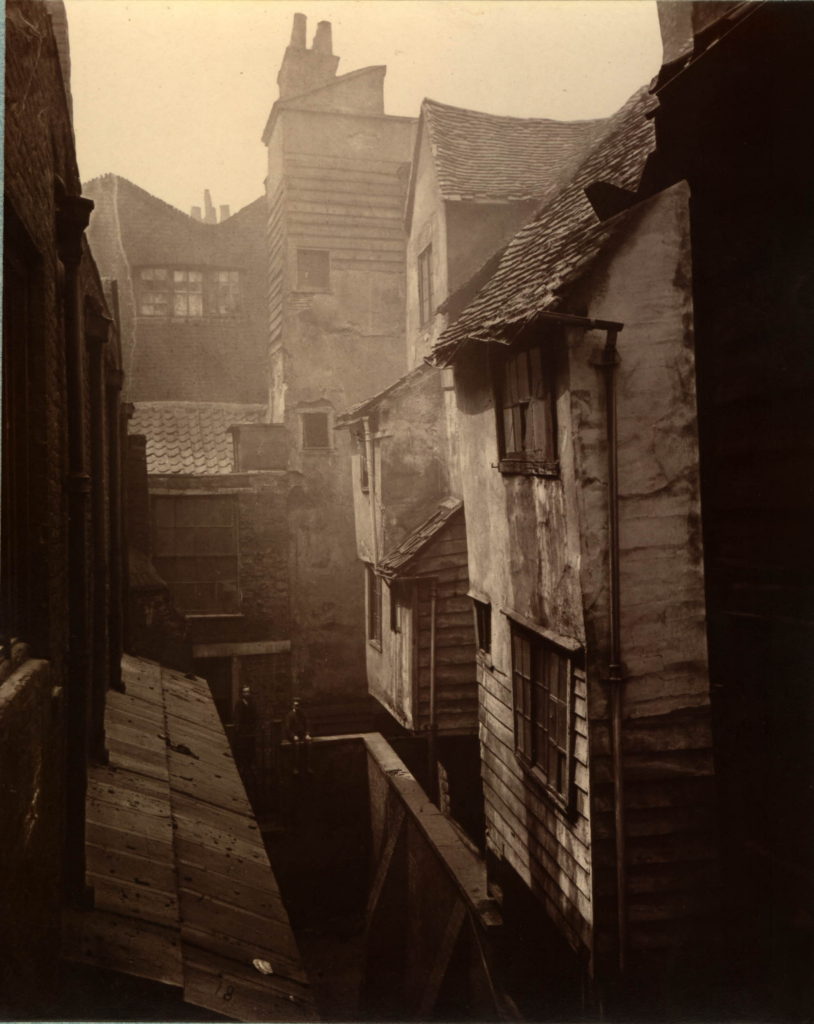

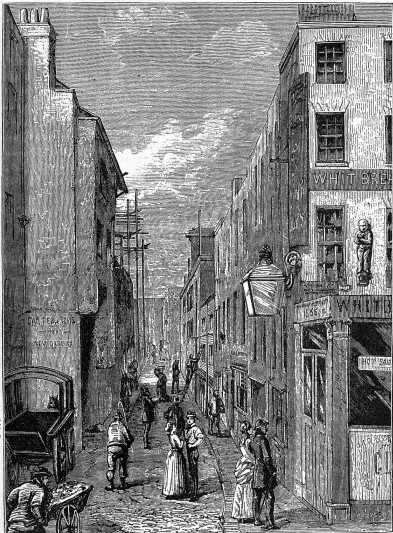

The British Museum has some photos of the alleys around Cloth Fair taken in 1877 by A. Bool for the Society for Photographing Relics of Old London. These photos (©Trustees of the British Museum) show ancient buildings crowded around narrow alleys.

The following photo shows not only the narrow alleys around Cloth Fair, but also how Cloth Fair has changed over the years. The photo shows a narrow alley. A small child is at the end of the alley and on the left are houses leaning over the alley to get a small bit of additional space for the upper floor.

Look to the right of the photo and there is a substantial stone building.

I found the above photos after I had walked along Cloth Fair, so I could not get a photo in the same position, however after looking again at my photos it was clear where the above photo was taken.

On the right in the above photo there are three arches at ground level. Above this, there is a roof, leading back to a higher stone wall with windows and drain pipes. Towards the end of the alley, the building on the right is higher still, with an angled roof.

Now look at the photo below and it is clear that the building on the right in the above photo is the side wall of the St. Bartholomew the Great.

The original photo was taken roughly were the furthest bollard is now located, looking towards the nearest bollard, which is roughly where the child was standing. Two of the three arches can be clearly seen, as can the roof above, the windows and drain pipes. Getting closer to the camera, the building rises a level with an angled roof, as in the original photo.

The houses on the left of the original photo were where the “Keep Clear” signs are on the road today. This alley was not Cloth Fair, but ran parallel to the church where Cloth Fair should have been, so how did this work?

Turning to the 1895 Ordinance Survey map provided the answer:

Cloth Fair can be seen running left to right across the map. Below Cloth Fair is St. Bartholomew the Great.

Look just above the church, and between the church and Cloth Fair, running half way along Cloth Fair is another row of houses with a narrow alley between the church and Cloth Fair. This is the alley in the photo.

The alley and houses have clearly disappeared since 1895, however that cannot be the full story otherwise there would be a much larger space today, where the alley, houses and Cloth Fair were located.

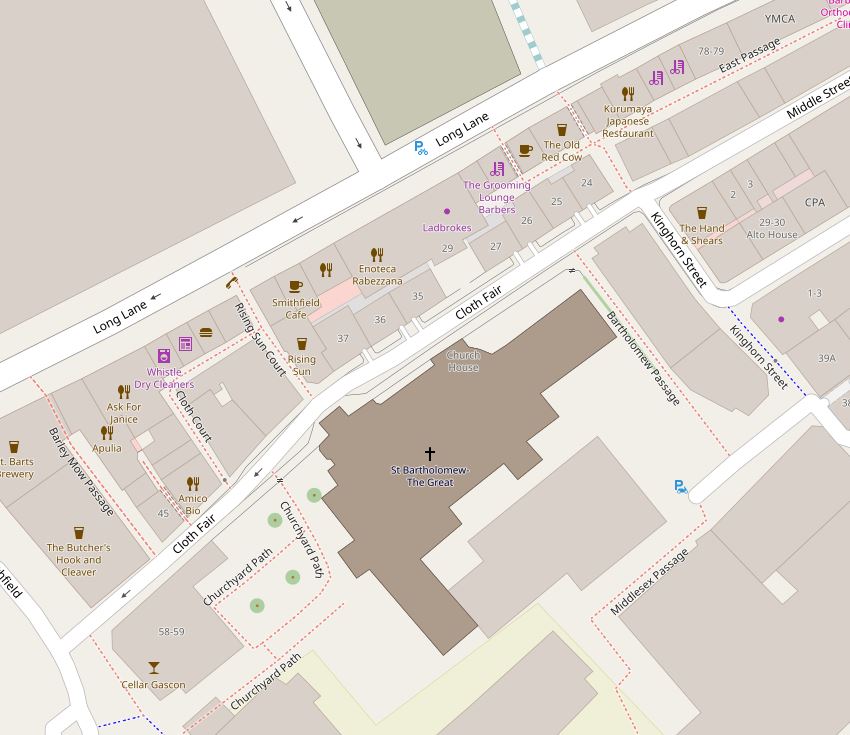

The extract from the map of the area today has the answer:

The angle of the route of Cloth Fair as it runs past the church to the right has been changed. In the 1895 map, the junction with Middle Street is slightly offset, today Cloth Fair runs straight into Middle Street. Cloth Fair today is also running parallel to the church.

The British Museum collection also has the following photo, which I believe is taken in the same alley, but this time looking in the opposite direction as to the photo above, now with the church of St. Bartholomew on the left of the photo. This is looking towards the where the alley exits onto Cloth Fair in the 1895 OS map.

In the photo below, the alley in the above two 1877 photos ran along the footpath on the left, and the majority of the road was occupied by the houses in the photo. The original Cloth Fair ran along the footpath and partly under the buildings on the right. In the above photo there is a building projecting out at the end of the low roof leading up from the bottom left of the photo. This is the entrance porch seen in the photo below with the black and white patterned roof.

So even along streets as old as Cloth Fair, we can never be sure we are actually walking along the route of the original street. Along this stretch of the street today we are walking along the old alley and where the houses once stood.

There are many other lovely buildings along Cloth Fair. This is the Rising Sun pub at Number 38. A pub has been at this location for a number of centuries. I can find newspaper reports mentioning the pub going back to the start of the 19th century, and the pub is (although not the same building), much older.

Cloth Fair would have been risky place to be in during the Bartholomew Fair. The are numerous reports of crimes in the area, many violent and plenty of thefts, including the following from the Rising Sun:

“On Monday se’nnight, some thieves during the busy period of the evening, it being at the time of Bartholomew Fair, broke into the upper apartments of Mr William Sawyer, of the Rising Sun, Cloth Fair, and carried off all the wearing apparel, some sheets, and two watches, &c., to the value in the whole of £60 with which they decamped, and have not yet been discovered”.

This is number 43 Cloth Fair, also on Cloth Court,

The building was home to Sir John Betjeman from 1954 for 20 years. He moved into the building after meeting Paul Paget and John Seely and seeing their restoration work in Cloth Fair. The building is now owned by the Landmark Trust.

Although Cloth Fair has lost many of the alleys that lined and led off from the main street, there are still a few that remain to give a limited sense of what the area was once like.

The buildings that line Cloth Fair are fascinating, as is the history of the street and association with the Bartholomew Fair, however after finding the photos of the alleys and the alley that once ran along the edge of the church, it was being able to place the alley, and the realisation that streets I thought were original have slightly changed their route over the years that was really pleasing.

It is these little details that make walking London’s streets so interesting.