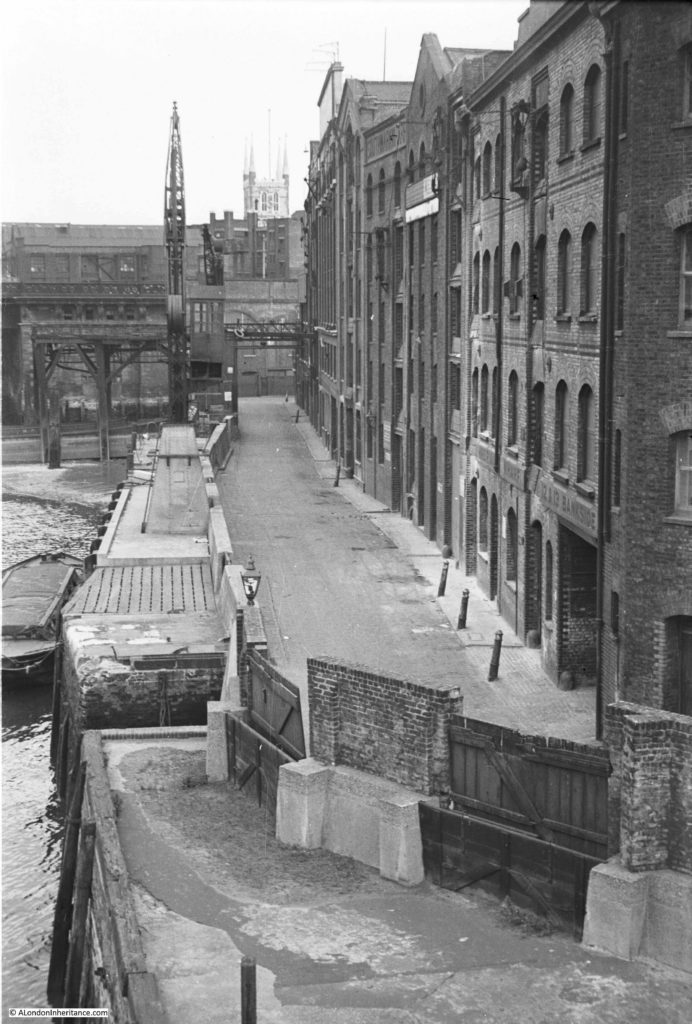

Last week I was at Southwark Cathedral. This week I have walked from the Cathedral to Southwark Bridge to look along Bankside back towards the Cathedral. This was my father’s view in 1953:

I could not take a photo from the same position for reasons which I will explain shortly, so I took the following photo from Southwark Bridge showing this part of Bankside as it is now:

This short stretch of Bankside is completely different from 1953. A straight length of river wall and walkway now lines the river between Southwark Bridge and the railway bridge into Cannon Street station. The warehouses have been replaced by two office buildings and the cranes and infrastructure along the river have long since disappeared.

The changes since 1953 also include where the Bankside walkway is located and the alignment of the river wall.

I could not take a photo in the same position as my father as I would be looking from the bridge straight into the FT building on the right. The river wall has been pushed further into the river and the edge of the buildings now cover the original Bankside roadway. In my father’s photo it was possible to look straight along Bankside and see the tower of Southwark Cathedral from the bridge. Today, this is not possible as the two new buildings obscure the view having been built over the original road (also Southwark Cathedral is hard to see due to the taller buildings directly behind).

The river wall has been straightened and pushed into the river. Look at the 1953 photo and at the far end is the railway bridge. To the left of the crane you can see the brick pier of the bridge extending into the river. Today, the edge of this brick pier is now aligned with the edge of the river wall and Bankside walkway.

The following extract from the 1895 Ordnance Survey map shows this stretch of Bankside which I suspect had not change that much in the almost 60 years between the map and my father;s photo. It shows Bankside lined with warehouses, wharves and cranes along the river’s edge.

There are a couple of features that interested me in my father’s photo. In the lower part of the photo is a solitary lamp mounted on the wall along the river and to the right is a large entrance on the ground floor of the building. What was this single lamp doing in this position?

Looking at the 1895 map, the large entrance to the building on the right is the entrance to Horseshoe Alley. Covered over by the building, but opening out to an exposed alley as it heads in land. Opposite Horseshoe Alley at the water’s edge is what appears to be an opening in the river wall down to the river which can also be seen in the photo above to the left of the lamp.

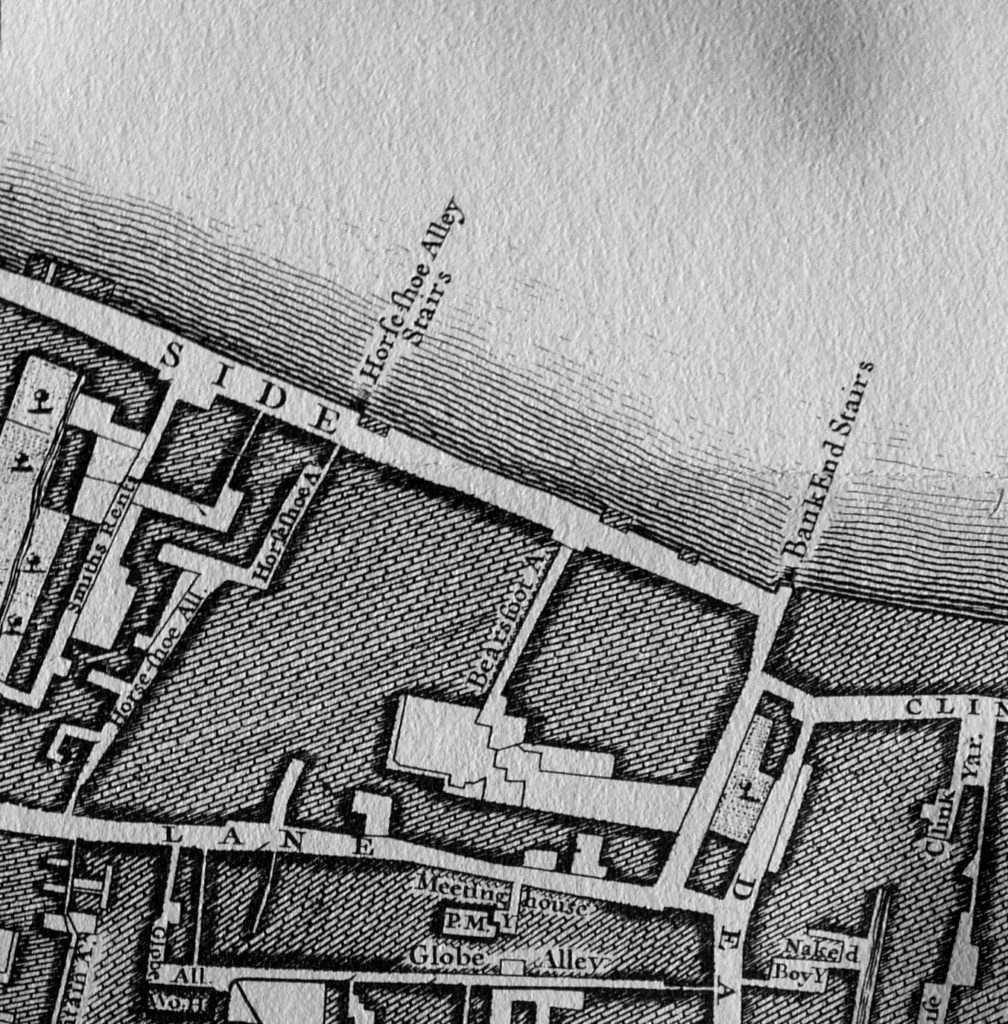

I then checked my copy of John Rocque’s, map from 1746. In the extract below, Horseshoe Alley is there, but also, leading down to the river is Horseshoe Alley Stairs.

So perhaps this single lamp was there to mark the position of the stairs and to guide those walking up and down what would have been rather dangerous and slippery steps down to the river.

Another feature that both of the above maps confirm is where Bankside ended at the appropriately named Bank End. It is at the edge of Bank End that the bridge carrying the railway across to Cannon Street station now runs. The Rocque map confirms that Bankside terminated here well before the railway bridge was built.

The approach road to Southwark Bridge runs over the street marked Smiths Rents on the left in the 1746 map.

There is an interesting story in the South London Press on the 4th March 1882 about Horseshoe Alley that shows how much flooding there was along this area of Bankside and the precautions put in place (or sometimes not) in an article titled: “The Floods in Southwark. How ‘Not To Do It’ “

The article reports on an inquiry by the St. Saviour’s Board of Works into flooding along Bankside:

“The chairman said that the board had been in communication with the Metropolitan Board of Works prior to the overflow with reference to the work to be carried out; and he apprehended that it was in consequence of that not being done that the flood took place.

Mr Stafford asks: But did we not delegate one of our officers to attend to the question of floods specially, in order that the flood-gates may be closed at the proper time?

The surveyor (Mr Greenstreet) said that was the case. The board had appointed the clerk of the works to look after the barriers. With reference to the flood on Sunday week, he (the surveyor) was himself at Christchurch at 1 o’clock in the day. The clerk of the work’s unfortunately had only two men with him, though on such occasions he generally had four. All the dam-boards that were in use were at once put up so as to prevent the overflow of the water; but he found that at one important point-viz., Horseshoe-alley, the barricade had been removed. The water could not, therefore be prevented from coming in there, and it came up with such rapidity – more rapid, in fact, than on any previous occasion of which he had experience – that it washed away all the clay at Bank End. he found that nearly half of the dam-boards along Bankside were in an incomplete state, but some were now in proper order. The fact that the water overflowed was a pure accident that could not be prevented.

Mr Stafford asked the surveyor, with reference to the board at Horseshoe-alley, whether, prior to the flood he was aware it was not in position.

The surveyor replied in the negative. He only noticed its absence on the Sunday when the flood occurred, and it then struck him that the board must have been stolen.

Mr. Evans mentioned that on the Sunday in question he happened to be passing over Southwark Bridge when the water was coming up, and he immediately repaired to Bankside. He met the inspector and along with that officer they did what they could to prevent an inundation. Three men were employed to put up the barricades, and they had since complained to him (Mr. Evans) that they only received half a crown each for their work. As regarded Horseshoe-alley, he found that there were no boards there, and he took it upon himself to advise the inspector of nuisances to do what he could.

Mr Hale asked the surveyor how long it was since he had ordered the removal of the boards at Horseshoe-alley. The Surveyor replied that he had not ordered their removal and that it was impossible to say where the boards went. It is pretty well a month since it went.”

I suspect the surveyor may have lost his job as a decision on his future was postponed for a later meeting.

The flooding referred to happened on Sunday 19th February 1882. There were frequent floods along the Thames, however the river level for this flood was one of the highest and impacted a far wider area. There were reports of high tides and floods along the East Coast, but the greatest damage was done along the Thames.

The high tide on the morning of the 19th rose to above its normal height but did not give any cause for alarm, however it was the afternoon tide that went higher. By 2:30 pm the Trinity high-water mark at London Bridge had been reached. The tide continued to rise for another 30 minutes so that by 3pm it was now 2 ft higher than the Trinity mark.

Whilst some of the dams did hold, much of the Bankside and Blackfriars Bridge area flooded and there were bad floods in Lambeth. There was a heavy rush of water through Blackfriars Bridge Wharf with 2 foot of water flooding the surrounding streets. Men, women and children were reported to be “seen rushing about in all directions to find means of keeping out of the muddy water.”

The areas worse affected were Rotherhithe, Southwark and Lambeth on the south side of the river, and High Street, Wapping on the northern side. At St. Katherine’s Dock, the water level was recorded as being only 5 inches below the highest level ever recorded on the Thames which had occurred only a year earlier on the 18th January 1881.

The article mentions the Trinity high-water mark. I found the following on the river wall underneath Southwark Bridge on the north bank of the Thames. I believe it is one of the Trinity high-water marks:

Looking back at my father’s 1953 photo it is easy now to understand the structures along the left side of the street. Heavy concrete walls, with the access points secured by heavy wooden panels slotted into the edges of the concrete walls to form a watertight seal.

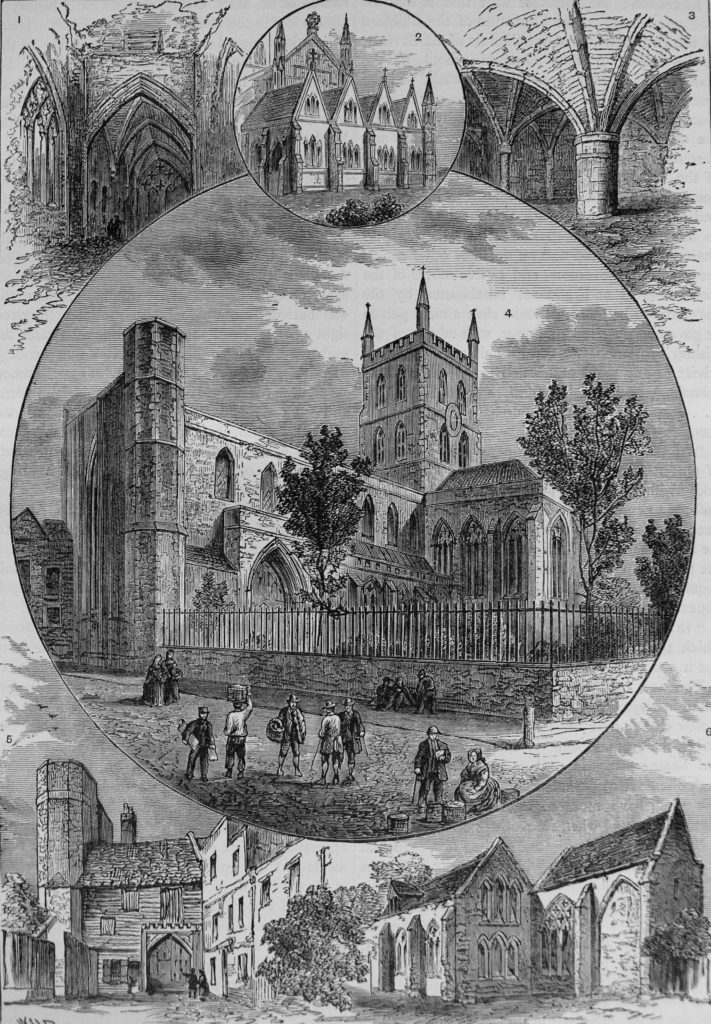

Apart from the bridges that form the borders to this stretch of Bankside, there is only a single building that remains from the time when my father took the 1953 photo and the 1895 map.

Although not visible in the 1953 photo, if you look at the 1895 Ordnance Survey map, there is a Public House marked on the corner at Bank End. The pub is still there and is now called The Anchor:

For part of the 19th Century the pub was called the Blue Anchor. In the 1953 photo there was only the relatively narrow street between the pub and the river, however today, with the straightening of the river wall out to the end of the brick pier of the bridge, there is a large open area in front of the pub – perfect for a beer on a nice day or evening.

The area on the left of the above photo is Bank End, as confirmed by the name on the side of the pub, so if you stand here, this is where Bankside ends.

Today, apart from the pub, this stretch of Bankside is rather bland and Horseshoe Alley and Stairs disappeared during the reconstruction which resulted in the river wall, walkway and buildings we see today. Stand here during a high Thames tide and it is easy to appreciate the challenges of protecting the land when all that was available to prevent an inundation were wooden boards .

I wonder what happened to the surveyor and if he had any role in the disappearance of the Horseshoe Alley dam-boards.

From Bankside To The Proud City

On a completely different subject, I recently found a copy of the film “The Proud City” on YouTube. The film tells the story of the planning for the post war reconstruction of London by Patrick Abercrombie and JH Forshaw. The film includes many views of London, along with Abercrombie and Forshaw explaining the background to the plan, along with some wonderful large scale posters of the maps that would be in the printed report along with models of areas to be redeveloped. The following screen shots from the film show some examples.

I wonder what happened to these large wall maps. I would love to have them on my wall. I featured a number of them in my post on the 1943 plan for post war reconstruction here.

I wonder what happened to these large wall maps. I would love to have them on my wall. I featured a number of them in my post on the 1943 plan for post war reconstruction here.

The film is very much of its time, but is 25 minutes well spent to see some fascinating film of London and to understand the thinking behind the Abercrombie and Forshaw plan.

The Proud City can be found here.