Clink Street in Southwark is close to Southwark Cathedral and Borough Market, and the street is part of the busy walk along the south of the river. Converted warehouses line the river side of Clink Street, but on one part of the southern side of the street, a remarkable survivor, the Great Hall of Winchester Palace can be seen; the Southwark residence of the Bishops of Winchester.

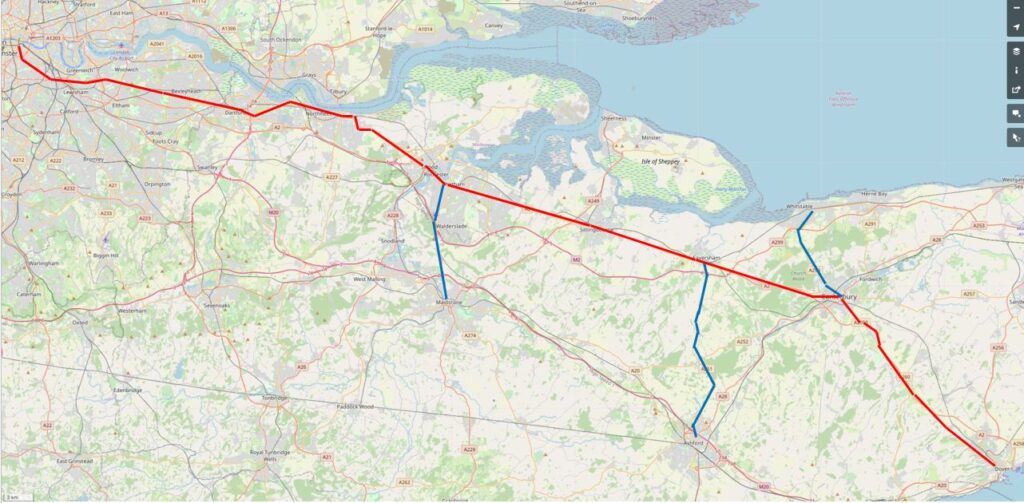

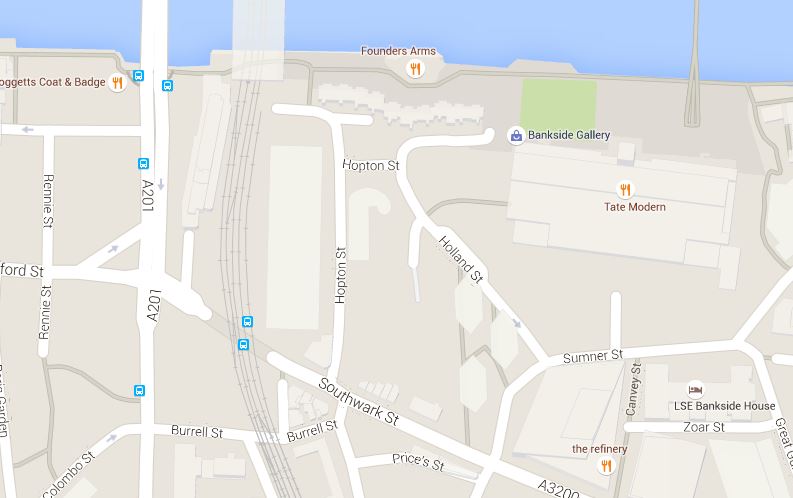

The following map extract shows the location – the green rectangle towards the middle, top of the map is the part of the palace that can be seen alongside Clink Street (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

The first evidence of a palace for the Bishops of Winchester dates back to the 12th century, with an eastern boundary wall, and some building of stone construction.

The 13th century saw the expansion of the palace estate with some major construction work. This work included a number of two storey blocks, a hall, chapel and courtyard. Work also included improvements to the wharf along the River Thames.

The 13th century also included the surfaced road that would become Clink Street, with the name Clink Street being in use by the start of the 17th century.

One of the earliest references to Winchester House (as it was also known) comes from the life of St. Thomas à Becket by William FitzStephen, who wrote that Archbishop Thomas received hospitality at the house of the Bishops of Winchester before making his final journey to Canterbury where he would meet his death.

The Bishops needed a London residence, not just for their religious duties. At the time there was not that much separation between religion and government, and the Bishops of Winchester also frequently held some of the great Offices of State.

The Palace was also frequently used for entertaining, and hosted events for the rich and powerful of the land. For example, in 1424 the wedding feast of James, King of Scotland, and Joan, daughter of the Earl of Somerset was held at the palace.

The palace appears to have been in possesion of the Bishops of Winchester through to the mid 17th century, when it was turned into a prison for Royalists during the Civil War. In 1649 it was sold for £4,380 to a Thomas Walker of Camberwell, but after the restoration of the monarchy, the palace estate was returned to the Bishops of Winchester.

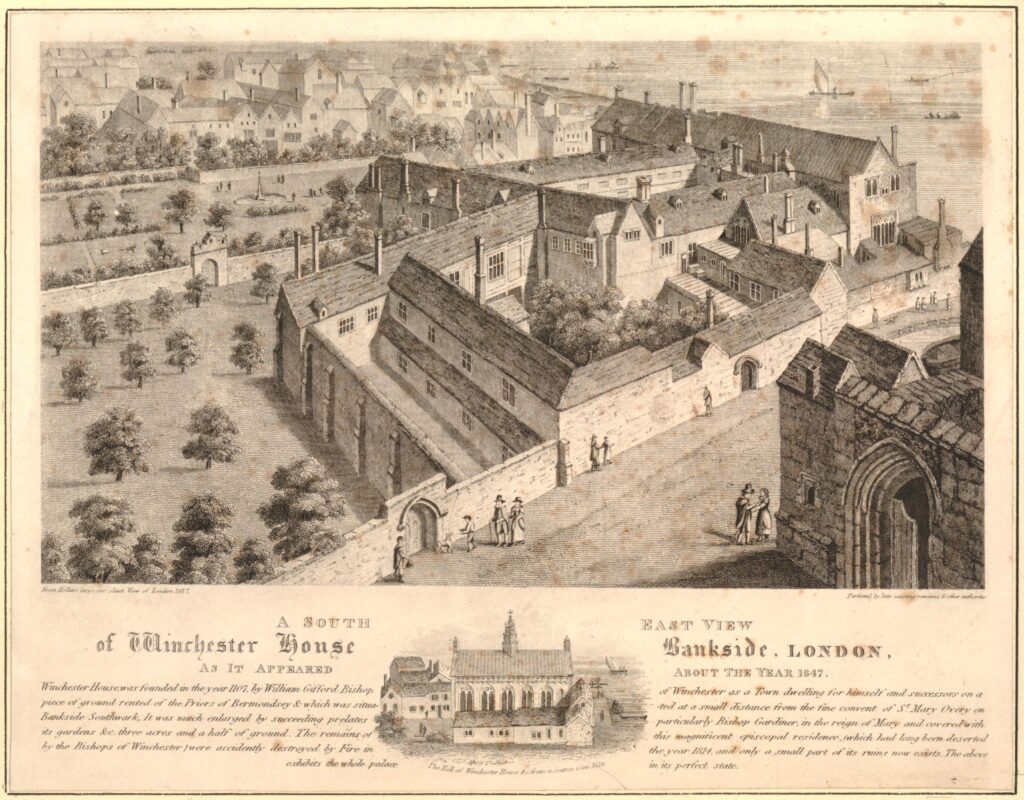

It was during the 1640s that a parliamentary survey of the palace was carried out, and around 1647 the artist Wenceslaus Hollar completed a drawing of the Palace, or Winchester House, the words Palace and House are frequently used in reference to the Bishops of Winchester residence (Prints in this post are ©Trustees of the British Museum):

Hollar’s drawing shows an extensive range of buildings alongside the river. The Great Hall is to the right, with the rest of the buildings housing accommodation blocks, storage, kitchens, a chapel and stables. There were also extensive grounds to the palace.

The text below the above print provides some detail about Winchester House: “Winchester House founded in the year 1107 by William Gifford Bishop of Winchester as a Town dwelling for himself and successors on a piece of ground rented of the Priors of Bermondsey and which was situated at a small distance from the fine convent of St Mary Overy on Bankside Southwark. It was much enlarged by Succeeding prelates particularly Bishop Gardiner, in the reign of Mary and covered with its gardens &c. three acres and a half of ground”.

The small drawing at the bottom of the print shows the Great Hall, and it is the remains of this building that we can see alongside Clink Street today.

Although the palace was restored to the Bishops of Winchester on the restoration of Charles II, it was not really used again as their London residence. They now also had a property in Chelsea, provided to them by a 1661 Act of Parliament. Perhaps the location of their palace was not as pleasant for the bishops due to the growing population, the location of industry, entertainments and markets that were not allowed in the City of London, displaced to the south side of the river, and around the bishops palace.

The buildings of the palace were now let out to a large number of tenants and sub-tenants.

The bishops cannot have been too morally fussy in previous centuries, as the local area of Southwark and Bankside had a history of prostitution long before the Bishops left their palace in the 17th century, and they had a role in the governance, and profited from the brothels or “stews” that were found in the area. These had been banned in the City of London, so their south bank location, close to London Bridge was an ideal place to relocate.

The bishops let out buildings to be used as brothels and were also responsible for managing the “Ordinances Touching the Government of the Stewholders in Southwark under the Direction of the Bishop of Winchester” set out in the 15th century.

These ordinances dictate 36 specific rules and the fines associated with breaking these rules, for example:

- Number 6: Owners of a stew (stewholder) could not lend a sex worker more then 6s 8d (this was done to prevent a stewholder from having too much control over a sex worker)

- Number 9: a sex worker who paid the rent of 14d must be allowed to come and go at will. The owner of the stew must not interfere

- Number 15: a fine of 40s if a stewholder’s wife solicited at a stew

Perhaps the most serious was for any sex worker who established a relationship with their procurer or what we would now call a pimp. For this they would be fined, they would also suffer a dunking on the cucking stool, possible imprisonment, and would also be banished from the borough.

Stewholders were also banned from selling food, drink and fuel from their premises.

The Bishops of Winchester profited from the rents from the buildings occupied by the stews and from the fines generated by any transgression of the rules. They were also expected to ensure the rules were adhered to, and manage law and order in the area.

The association of the Southwark stews with the Bishops of Winchester was such that the sex-workers in the stews became known as Winchester Birds or Winchester Geese.

The Bishops of Winchester probably made a considerable sum from the rents and fines, and it would be interesting to know if as supposedly religious men, they had a moral conflict with making money from women involved in sex work.

If they did feel any moral responsibility, it did not extend to the treatment of these women after death who were buried in unhallowed burial grounds, many at the nearby Cross Bones burial ground, today on the corner of Redcross Way and Union Street.

The Southwark stews were closed in 1546 when Henry VIII banned them.

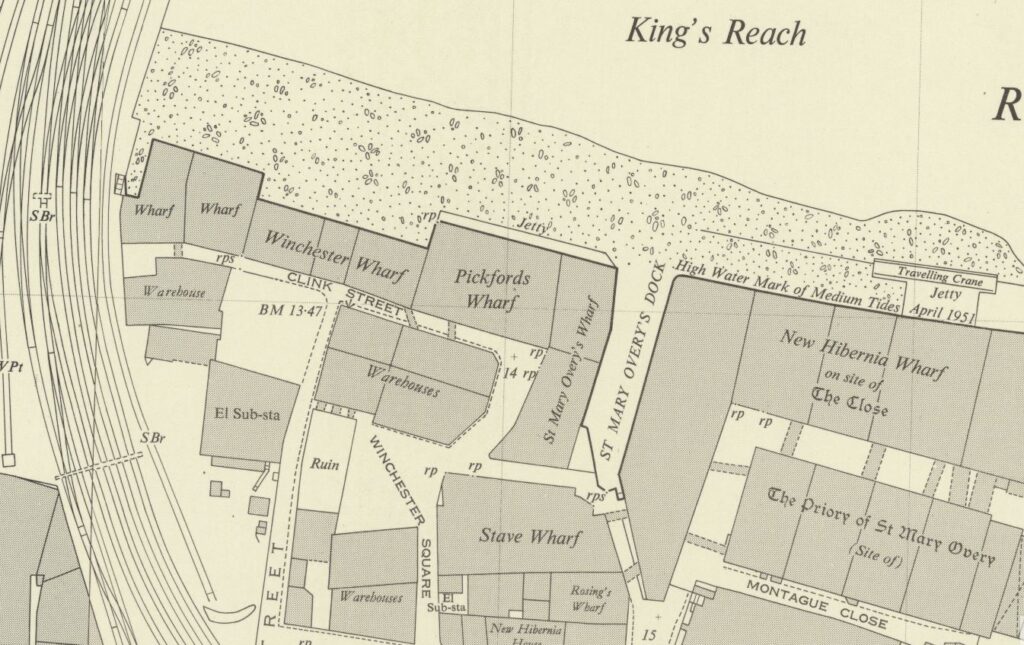

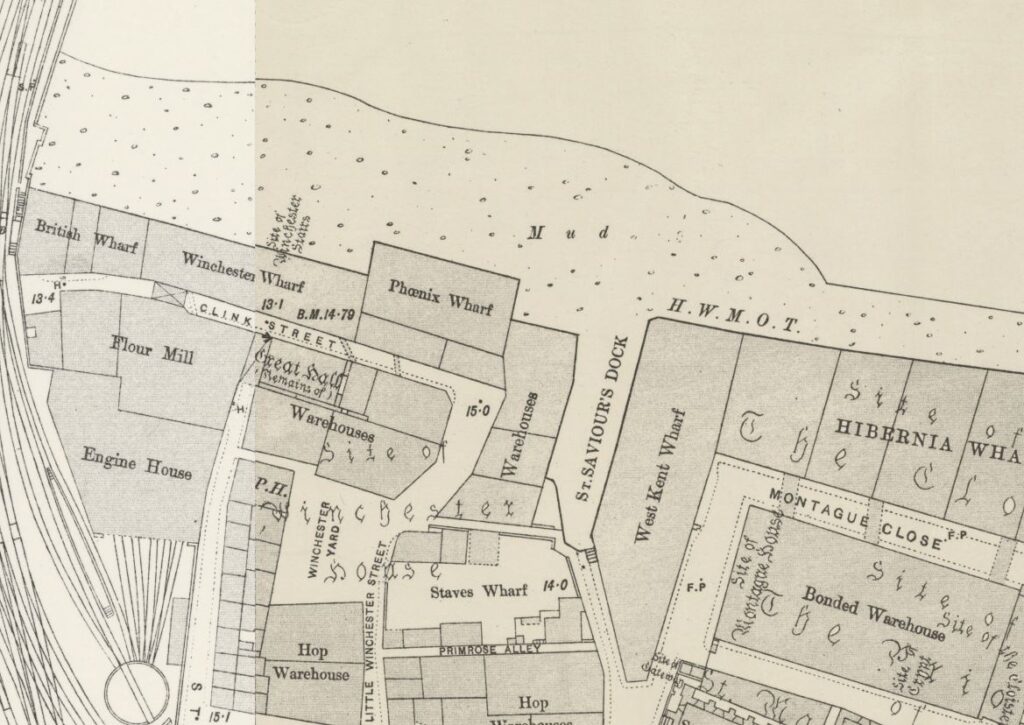

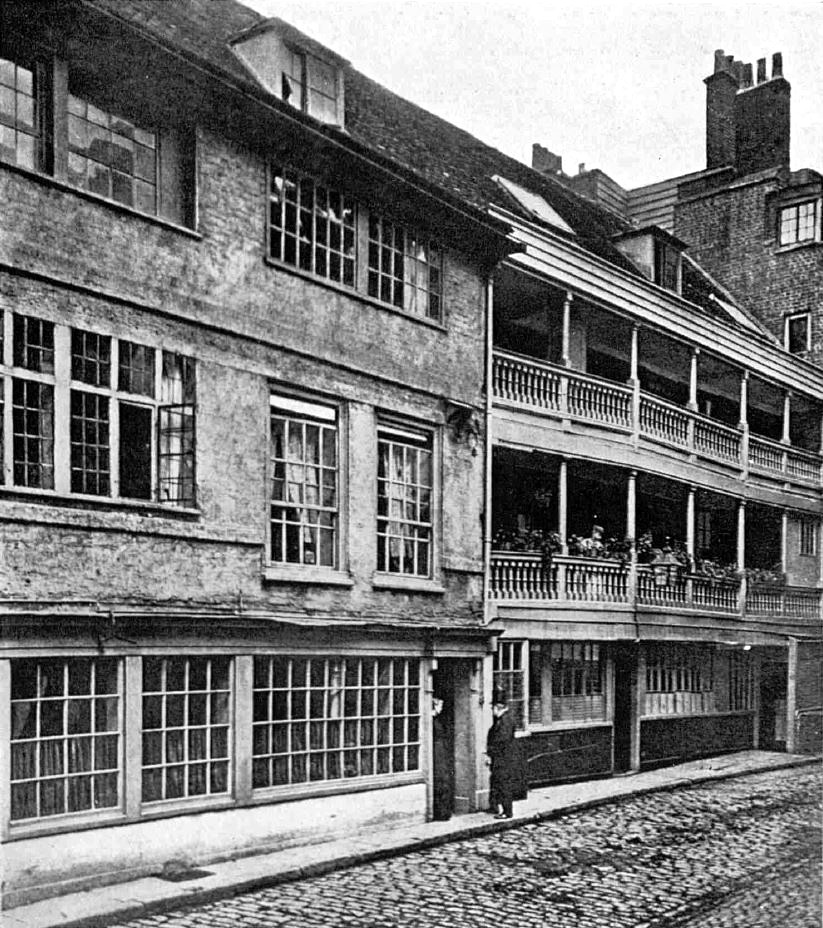

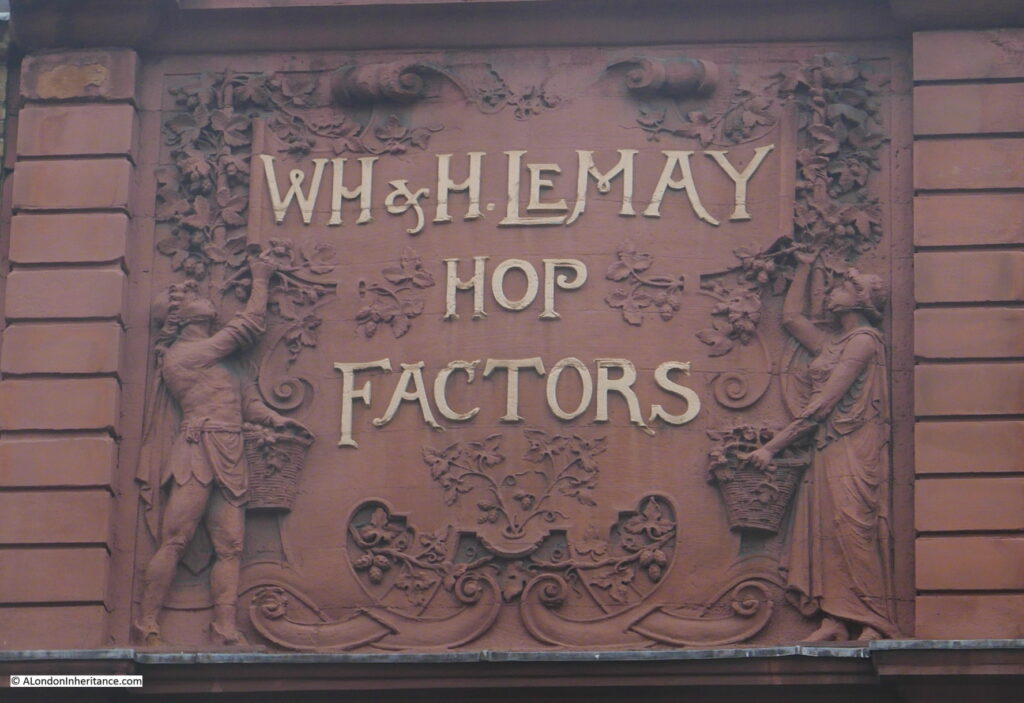

During the late 17th and 18th centuries, the land occupied by Winchester Palace was further broken up and sold. Warehouses and docks now occupied the area as trade along the river expanded, and walls that remained from some of the old palace buildings were included in the new structures that grew up along the river and Clink Street.

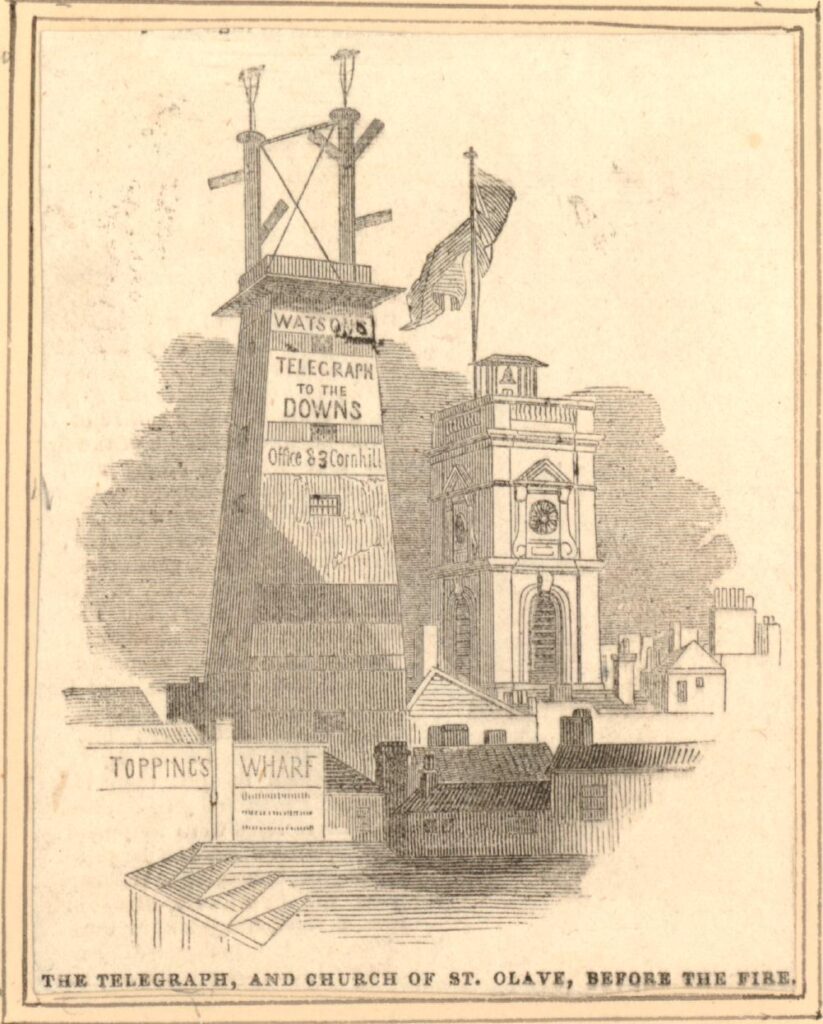

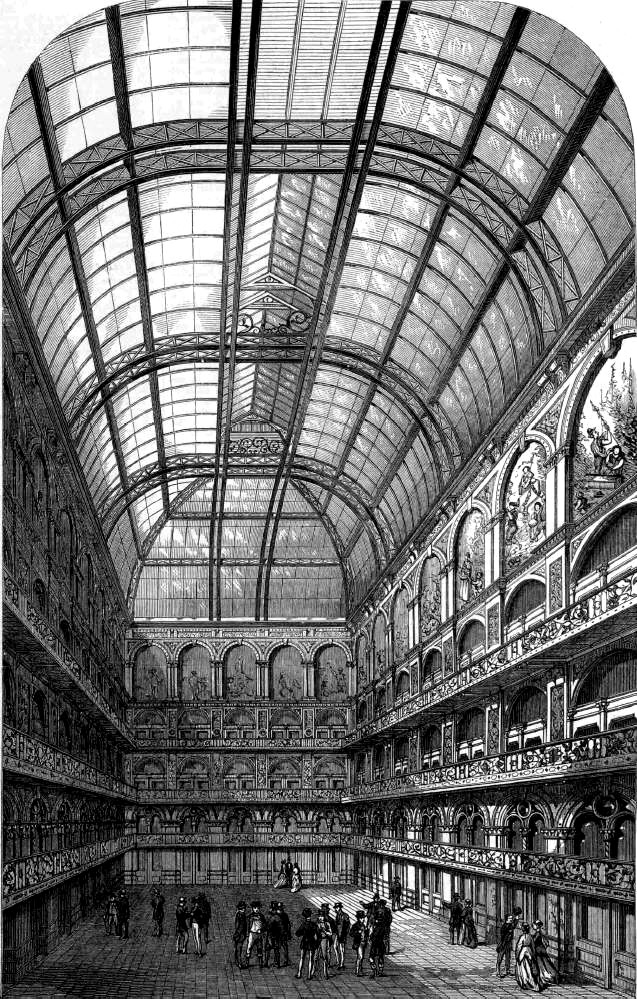

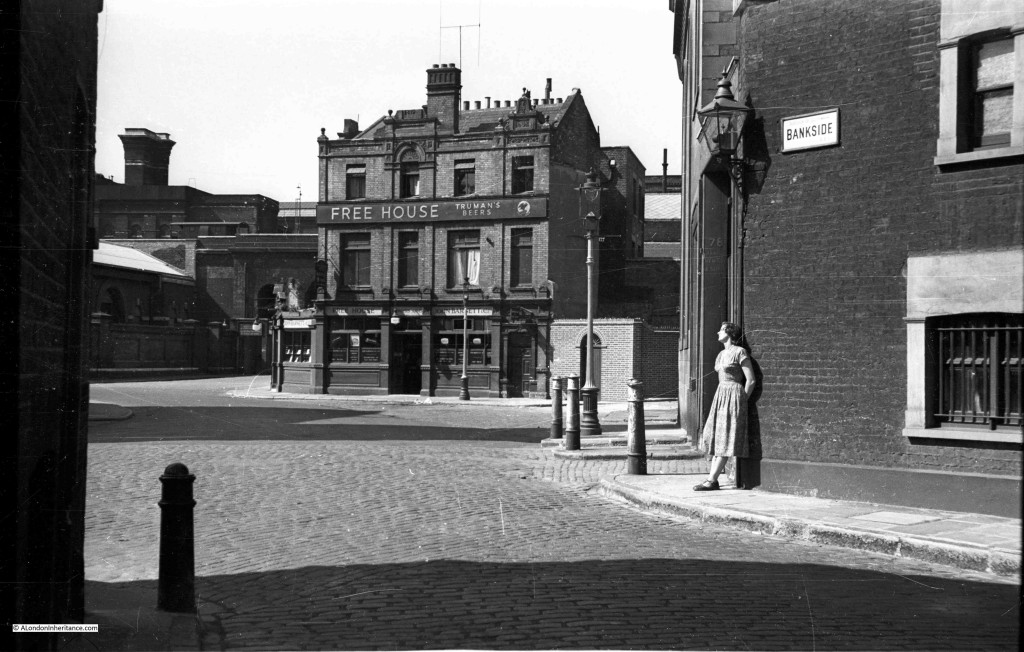

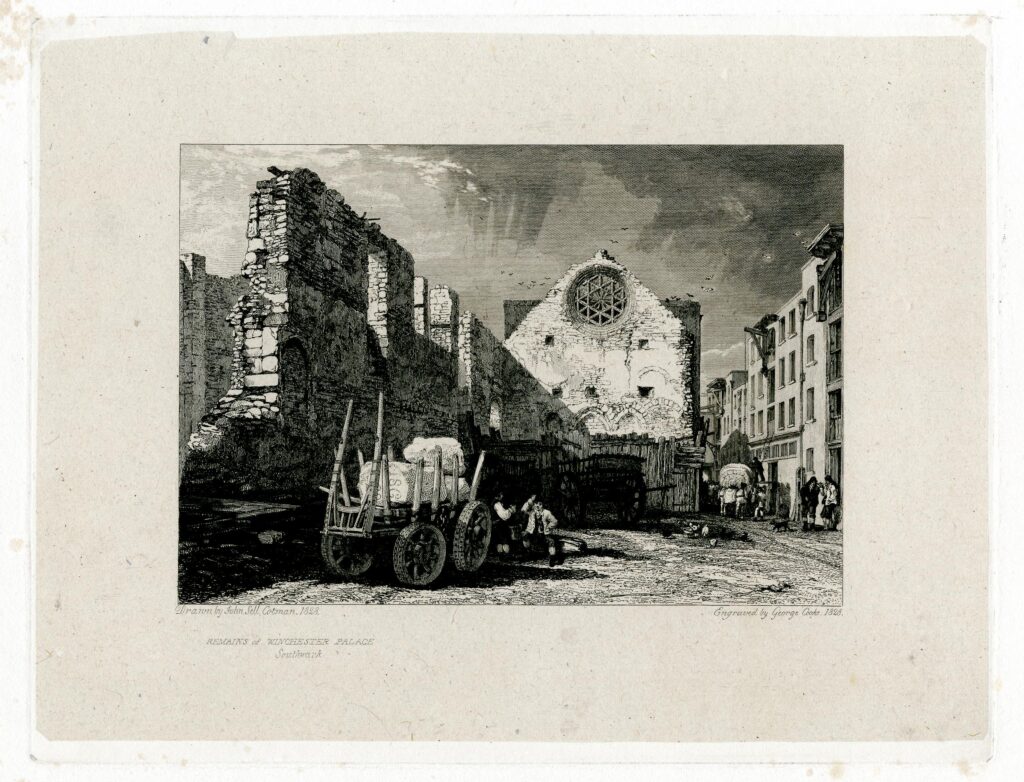

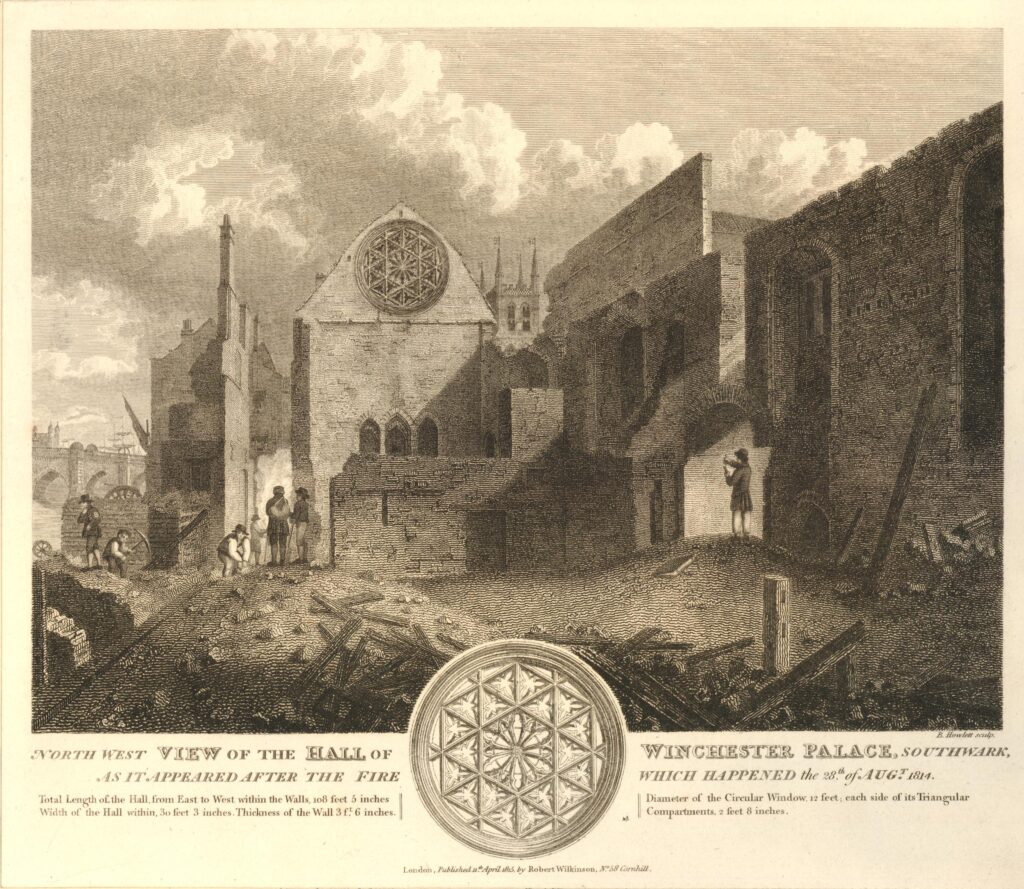

As was common in the 19th century, in 1814 a large fire destroyed a number of buildings in Clink Street, but whilst the fire appears to have destroyed later building, it did reveal part of the old Great Hall of Winchester Palace, and the following print from 1828 shows the remains of the Great Hall exposed after the fire, looking very much the same as they appear today.

The following photo shows again the west wall of the Great Hall and Clink Street alongside. The three openings that look to be windows were doors from the first floor of the Great Hall to the kitchens on the other side. The space below was occupied by an undercroft or cellar.

A small part of the southern wall of the Great Hall remains, up against the west wall. A ground floor door below with a first floor doorway above:

In the years after the 1814 fire, warehouse space along this part of river was in short supply, so it would not be long until a new warehouse was constructed over the site of the Great Hall, however, the approach of minimising costs by including any existing stone or brick structures into a new build continued, and the west wall and rose window of the Great Hall were included in the new warehouses.

There was some damage to warehouses in the area during the last war, however this does not appear to include the two warehouses that had been built either side of the west wall. In 1943 a Mr. Sidney Toy, of the Surrey Archaeological Society removed the brickwork on the seperating wall on the 3rd and 4th floor of the warehouses, and found the rose window, still showing blackened markings from the 1814 fire and with parts missing, and used in other parts of the structure.

There have been a number of early excavations of the palace, such as a 1962 excavation on the site where a new warehouse was planned. The major excavation of the site of Winchester Palace took place during 1983 and 1984. These excavations revealed a considerable amount of evidence of the original palace, including parts of the eastern range of the early 13th century building which were found under the current location of the Cafe Nero, on the corner of Palace House.

The following photo shows the other side of the west wall. The majority of the wall has been covered over by a glass frame that appears to be part of the new building to the right. The edge of a Pret coffee shop can be seen to the right.

In the above view we can again see the three doors that led through to the kitchens that would have occupied this space.

The following print from 1815 shows the same side of the wall as in the above photo. The print was a year after the 1814 fire.

Behind the wall we can see the tower of St Mary Overy (today Southwark Cathedral), and on the left is London Bridge. The text at the bottom of the print provides some details as to the size of the Great Hall:

- Total length of the Hall from East to West within the Walls, 108 feet, 5 inches

- Width of the Hall within, 30 feet 3 inches

- Thickness of the Wall, 3 ft, 6 inches

- Diameter of the Circular Window, 12 feet

- Each side of the Triangular Compartments (of the window) 2 feet 8 inches

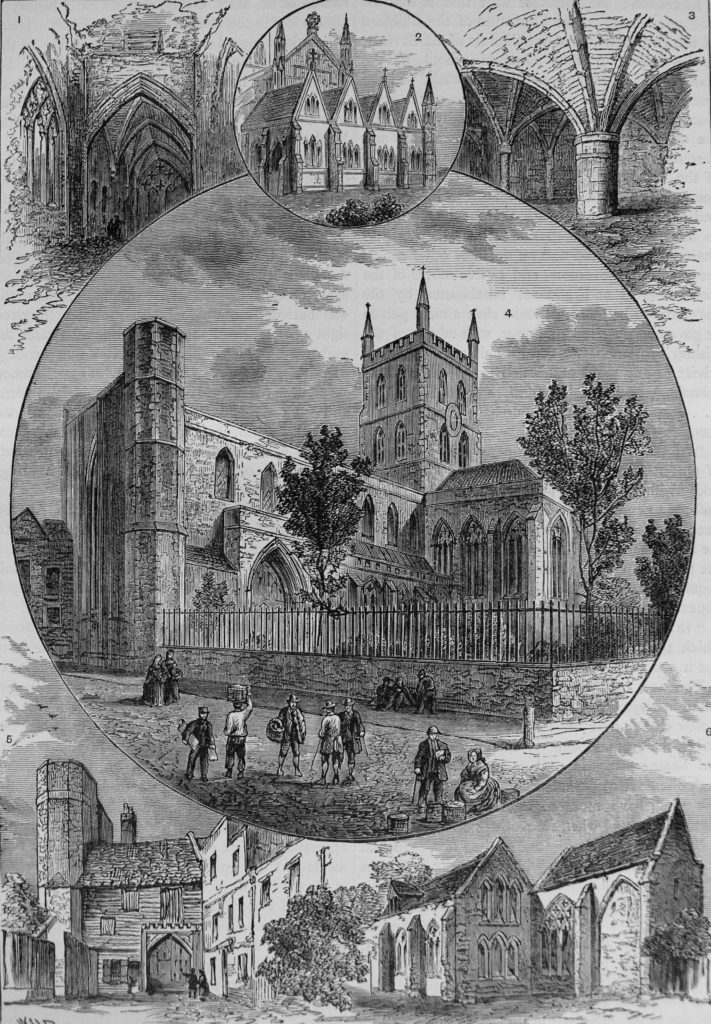

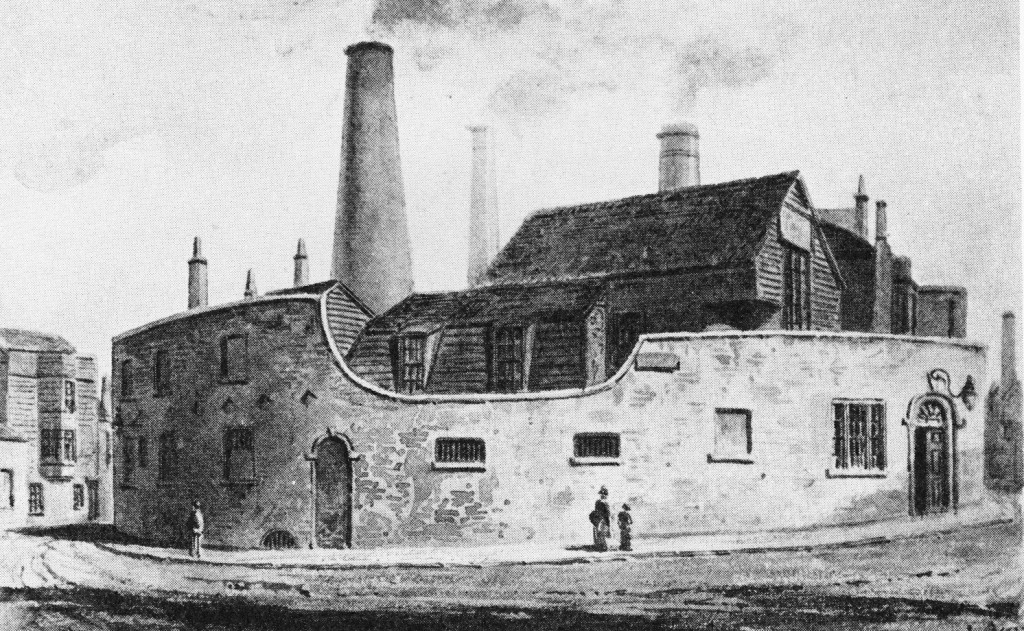

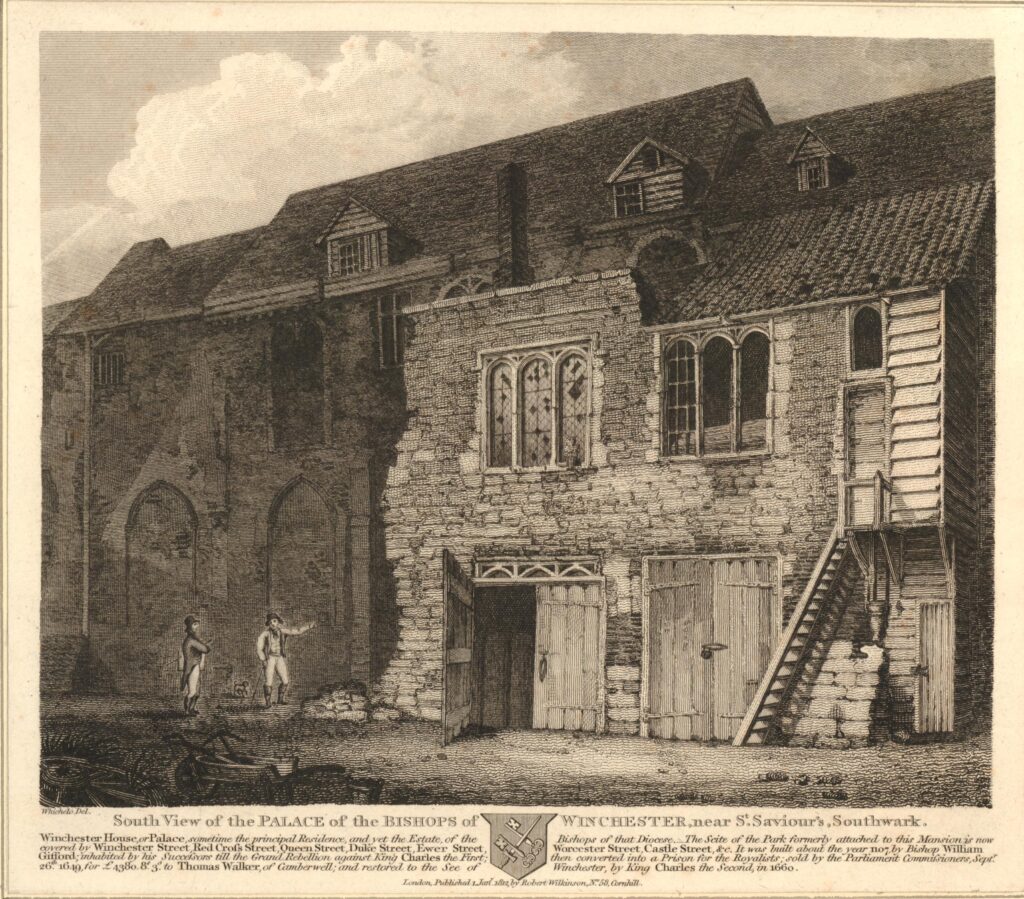

The following print is dated 1812, so before the fire of 1814.

The print shows the south view of the Palace of the Bishops of Winchester. It is not clear whether it is a view of the Great Hall, however it does show the state of the buildings just over 150 years after the Bishops of Winchester had left their palace, and the buildings had been sold and let to multiple new owners and tenants.

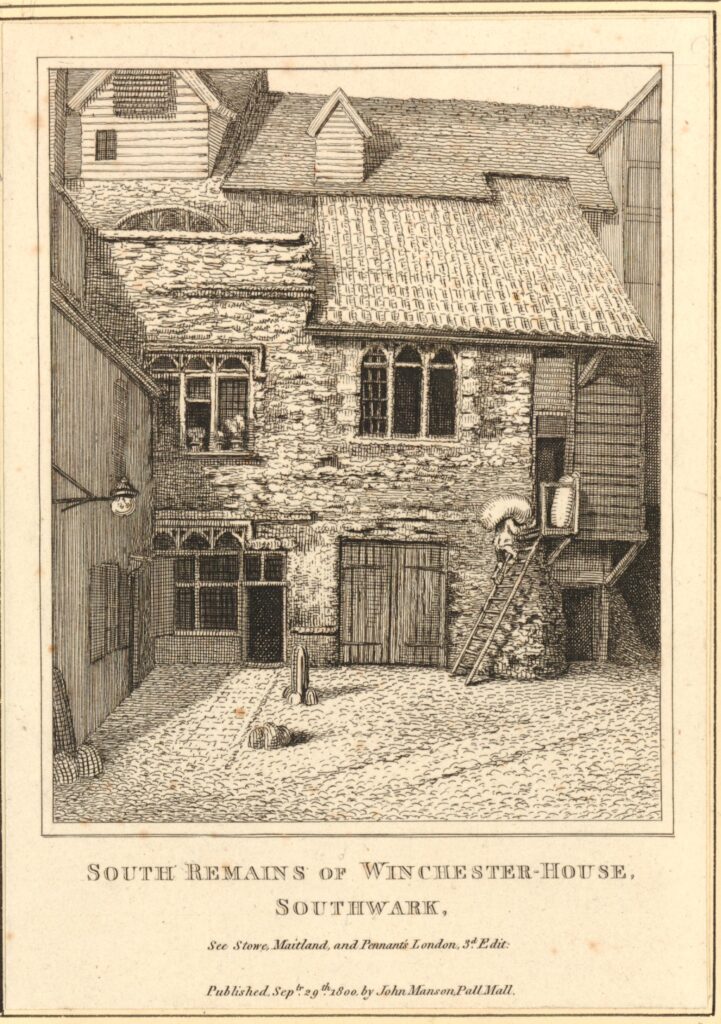

It is interesting to compare the above view, with the following view of the same building on the right of the above print. This print is dated 1800, so just 12 years before the above print.

Given the age of the west wall of the Great Hall, and the amount of rebuilding over the centuries, it is a remarkable survivor from the original Winchester Palace.

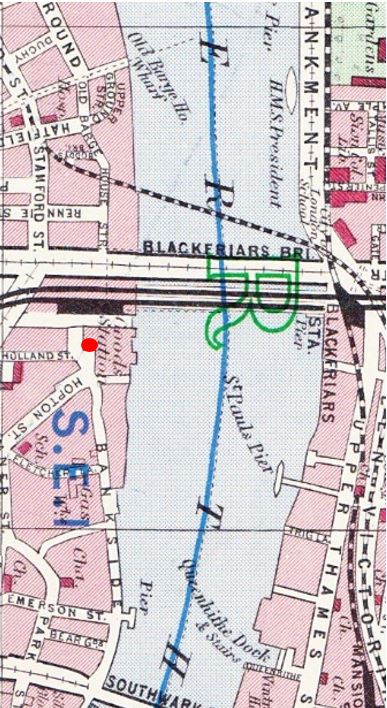

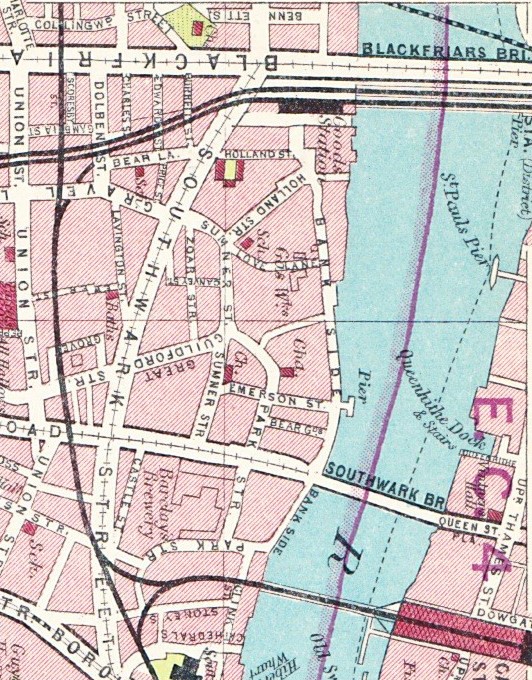

The following map extract is from a map of the Parish of St. Saviours Southwark by Richard Blome (late 17th century but published by John Stow in 1720). Clink Street is in the centre of the map, and the location of the Great Hall is under the word Street.

There is no mention of the palace that was once of considerable importance, so perhaps by the time of the above map, it was just another part of the buildings that lined the streets of the area. The white space in the centre of the block bordered by Clink Street and Stony Street is probably one of the old courtyards of the palace, possibly the space in front of the buildings in the above two prints from 1800 and 1812.

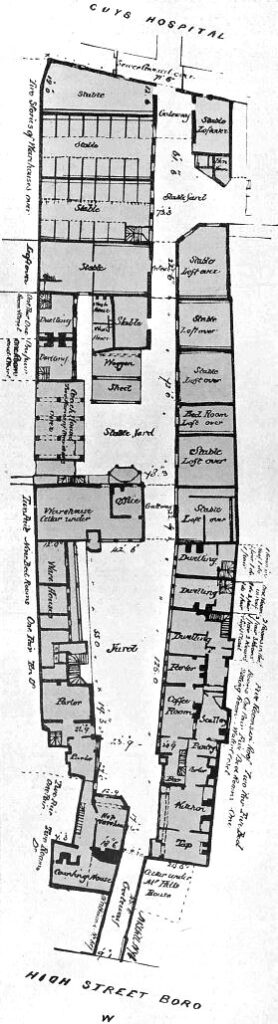

The palace occupied a far larger area than the remains of the Great Hall we see today. The Museum of London Archaeology Service published a richly detailed report in 2006 (Monograph 31) covering the history of the palace and focusing on the excavations of 1984 and 1985 and the finds discovered under the new and redeveloped buildings that occupy so much of this area.

The wall of the Great Hall has survived for so long because it was included in the structure of later buildings. This is how a number of other very old structures have survived in London, for example the Roman and Medieval bastions at Cripplegate and much of the Roman wall.

When we rebuild today, the approach seems to be a complete demolition of the previous building, including all the foundations and basements. It is interesting to consider how much 20th and early 21st century architecture will remain to be discovered in whatever form London takes in the future.

When the weather improves, and we can go out walking, sit outside the Pret with a tea and sandwich, in what was the kitchen of the Great Hall, and imagine the feasts that were prepared here and taken through the doors into the hall.