There are a few places in London where I can stand in exactly the same position as my father and the view is almost identical. In Winchester Walk, approaching Southwark Cathedral, the subject of this week’s post, is one of these locations.

My father took the following photo of the Cathedral in 1953 from Winchester Walk.

My 2017 photo from the same location:

I managed to get the alignment between these two photos almost exactly the same. The differences between the two are mainly cosmetic and if I had been there early in the morning with no people around and converted to black and white the photos would have been almost identical, amazing considering they are 64 years apart. The roof and air vents on the Borough Market building on the right are identical as is the roof line of the buildings on the left including the railing around the top of the wall at the base of the roof.

When I take photos at places where the view and surroundings are almost identical, knowing who was standing at this exact same place decades ago, it does bring home how quickly time passes and that we are all just very temporary occupants of these streets.

One of the differences between the two photos is the cleanliness of the buildings. It is perhaps difficult to appreciate how clean the buildings of London are today when compared to those of the city when the burning of coal in homes and factories was common across the city, and from the steam trains passing on the railway viaducts adjacent to the market and Cathedral.

Southwark Cathedral is in the background and Borough Market on the right – Borough Market being the reason why there are so many people around this area.

There has been a church on the site of Southwark Cathedral for many centuries, and the location close to the southern end of London Bridge, a river crossing point since Roman times, perhaps explains the importance of this location.

The first church on the site was possibly built around the 7th century, allegedly by a ferryman who used his wealth to fund the construction of the church. Edward Walford in Old and New London includes a story which also refers to a ferryman, but attributes the building of the church to his daughter, Mary Audrey. Old and New London records that this story came from Stow, who chronicled it as the report of the last prior, Bishop Linsted. Walford does then go on to state that this story has been much discredited.

I suspect we will never know who was responsible for the original church, however it was rebuilt in the 9th Century by the Bishop of Winchester and then in 1106 the church was re-founded by two Norman Knights, William Pont de l’Arche and William Dauncey as a priory for Augustine Canons. The church was dedicated to St. Mary and then later to St. Mary Overie. Walford in Old and New London suggests that Overie is a corruption of the surname of Mary Audrey, however I suspect this is part of the discredited story. The official explanation is that Overie means “over the river”.

In 1424 the church held its only royal wedding when James I of Scotland married Jane Beaufort, the daughter of the Earl of Somerset.

During the reformation, the priory was closed and the church taken by Henry VIII, when it became a parish church, dedicated to St. Saviour.

The church was purchased by the parishioners in 1614 and in 1689 the new tower was completed which is the tower we see today.

In the following centuries the church went through periods of decay and repair. The tower was in jeopardy on a number of occasions , Walford reports that once was due to vibration damage resulting from the ringing of the bells. The south-eastern pinnacle was struck by lightning and fell on the roof of the south transept. The wooden roof of the nave was demolished, followed by the original nave.

The church became Southwark Cathedral in 1905 to recognise the importance of the church and the considerable growth in population south of the river. The full title of the church retains the original dedications as the Collegiate Church of St. Saviour and St Mary Overie.

The following map extract from the late 17th century shows the church with the tower looking as it does today. To the left of the church is a small open area into which leads into Stony Street. This is the street from which the 1953 and 2017 photos were taken, however at some point it has changed its name to Winchester Walk. Borough Market now occupies the area south of the Cathedral on what was once Angel Court and the wonderfully named Foul Lane.

The current name Winchester Walk retains a link the area has had with the Bishops of Winchester. Winchester House or Palace once occupied a large area west of the Cathedral which included a hall of which the circular window can still be seen when walking from the Cathedral into Clink Street.

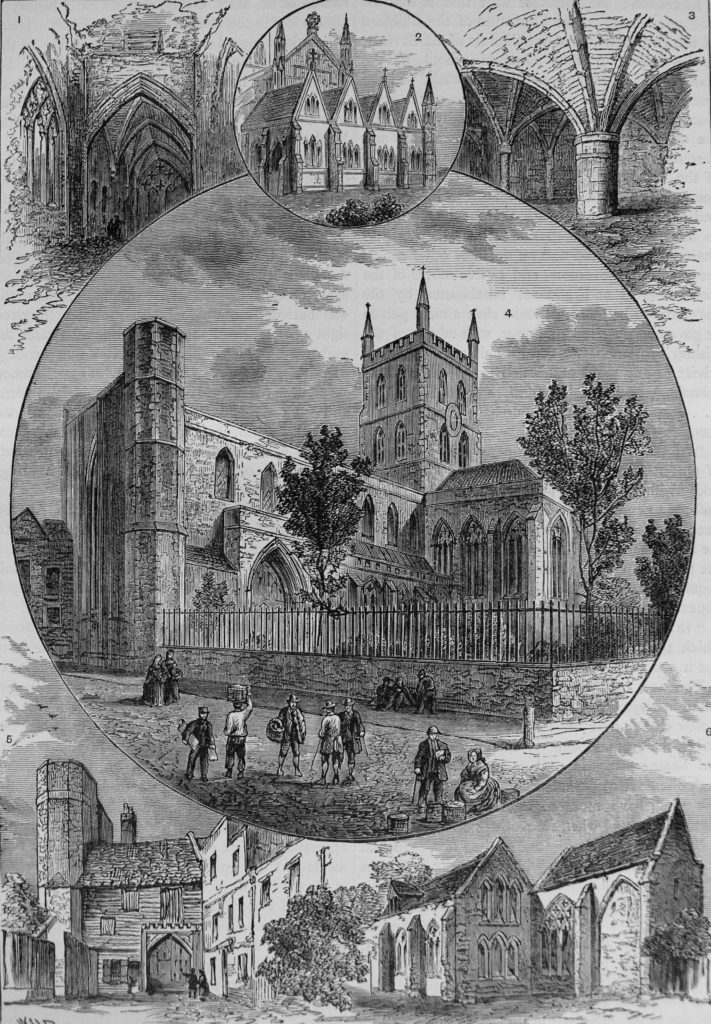

Views of Southwark Cathedral from Old and New London.

The top right drawing shows the part of the Priory of St. Saviour’s, the oldest part of the church and dating from the 13th century. This part of the church is still in existence and I will find this during a walk around the Cathedral.

Wenceslaus Hollar also made a number of drawings of the Cathedral including the following showing the south front of the church. The print was published around 1690, although certainly drawn much earlier as Hollar died in 1677. The church in the distance to the left of the Cathedral is St. Paul’s Cathedral so this could be a pre-1666 print. The spire on the tower of St. Paul’s must have been added by Hollar as it collapsed in 1561.

The future of the church was at risk during the 19th century when the church was still a parish church rather than a cathedral. During the 19th century, railways would cut through the south of London to reach stations along the south of the river such as Waterloo and cross the river to reach stations on the north bank. Walking around Borough Market shows how part of the market is enclosed within railway viaducts, and the impact of these on both the market and the church can really be appreciated from the top of the Shard.

The following photo shows the Cathedral to the lower right with the loop of railway viaduct heading round to the bridge to Cannon Street Station on the north side of the river.

There were proposals to demolish the church during the planning of the railways along the south of the river, fortunately these did not get put into practice, however the proximity of these viaducts clearly demonstrates the impact of the railway in the area around the Cathedral.

The area to the south west of the Cathedral and within the area enclosed by the railway viaducts is now occupied by Borough Market.

If you are there during a weekend, I recommend avoiding the crowds in Borough Market and visit the Cathedral instead. The interior of the church is fascinating and well worth a walk around.

The view on entering the Cathedral, looking down the nave towards the Choir.

The following two photos show some of the medieval roof bosses from the 15th century wooden ceiling, installed following the collapse of the earlier stone ceiling.

At the end of the nave is the Shakespeare memorial. The carved figure of Shakespeare is from 1912. Sir Walter Besant in London, South of the Thames mentions that Shakespeare’s brother Edmund was buried in Southwark Cathedral.

The tomb of Bishop Lancelot Andrewes who died in 1625. Andrewes was one of the translators of the King James version of the Bible.

At the eastern end of the church is the retro choir. This is from the 13th century and is the oldest part of the Cathedral still standing (see the drawing of the retro choir in the drawings from Old and New London above).

There is an open archaeological excavation outside the main church which I will come to later. This shows a 1st Century AD Roman road and has an information panel which shows that the original Watling Street ran along the eastern edge of the church, just outside the windows that run along the left of the photo above. The road cut through the far corner of the church.

The majority of effigies are carved in stone, however Southwark Cathedral has a rather unusual effigy carved in wood which dates from the 13th century.

There is also an effigy of the rather shrunken body of Thomas Cure of Southwark who died on the 24th May 1588.

This superb wooden chest once held all the parish records. Made by German immigrants in the parish, it was given to the church in 1588.

A wonderful model of the church, although a couple of the pinnacles on top of the tower appear to be missing, perhaps recreating the lightning strike that brought down one of the pinnacles onto the roof of the south transept.

During my visit the High Altar Screen was partially hidden behind an artwork. The High Altar Screen dates from 1520, but with later added detail. The screen consists of carvings of saints and those who have been connected with the Cathedral.

Looking down the Nave from the Choir.

The painted ceiling on the base of the tower.

An epitaph to John Trehearne, Gentleman Portar to King James the First.

The epitaph reads:

“Had Kings a power to lend their subjects breath Trehearn thou should’st not be cast down by death. Thy royal master still would keep thee then but length of days are beyond reach of men, nor wealth, nor strength, nor greatmen’s love can ease the wound death’s arrows make. Thou hast these in thy King’s court good place to thee is given. When thou shalt go to ye King’s Court of Heaven.”

A salutary reminder that no matter your wealth or power, there is no escape from death.

Along the northern side of the church is the Harvard Chapel which is named after John Harvard, the benefactor of Harvard University who was baptised in Southwark Cathedral, or St. Saviour’s as it was in 1607.

John Harvard was born in Southwark in 1607. He emigrated to America in 1637 and settled in Charlestown where he became a minister. He was only there for one year, as he died in 1638. He left his library and part of his estate to the college that had been established two years earlier and which would take his name.

The stained glass window in the Harvard Chapel was given to the church by the US Ambassador in 1907.

Also within the Harvard Chapel is a tabernacle designed by Augustus Pugin in 1851, the year before his death in 1852. It was Pugin who was responsible for so much of the design of the Palace of Westminster, including the Elizabeth Tower.

The tomb of John Gower. a poet to King Richard II and Henry IV. His head is resting on three books representing three of his greatest works.

The railway viaduct and market now occupies part of what was the churchyard of the Cathedral. There are some steps in the south-east corner of the churchyard from where the difference between the quiet churchyard of Southwark Cathedral and the crowds of Borough Market can be appreciated.

There were a fair number of visitors to the Cathedral during my visit, however what most people seemed to miss was perhaps one of the most interesting features. Walk back out the entrance to the Cathedral and there is a corridor where the Cathedral Shop is located. At the end of this corridor is the result of some of the archaeological excavations that took place prior to the building of the rooms on the north-side of the Cathedral in 1999.

The excavations show the layered history of the Cathedral, starting with the remains of a Roman road from the 1st Century AD, 12th Century foundations of the Norman Priory, 17th Century Delft Kiln, 18th Century stone pavement and a 19th century lead water pipe.

The remains of a 1st Century Roman road between the walls of the cathedral and the wooden retaining panels.

The information panel explains that the Roman road was a smaller road running diagonally across the church and appears to be running up to the river to meet at the same place where Watling Street met the river.

Lower right are 12th Century remains of the Norman church. In the middle is the 17th Century Delft Kiln and at the top is the lead piping and pavement.

Looking along the excavations with a coffin behind the kiln.

It is good to see these features in situ rather than as isolated exhibits. They show the layered history of London’s past and how London has always been built on earlier versions of the city.

It is also not just the stones of the city that have a layered history. All those who have lived and worked in the city over the centuries are also part of these layers, and it is this that I feel part of (although on a very much shorter time span) when taking photos in the same locations as those from 60 and 70 years ago.

The only time I’ve been to Southwark Cathedral was for a charity do. I was overwhelmed and always meant to return but never have!

Well worth a return visit Sarah if you get a chance. As well as the Cathedral, make sure you see the exhibit of the archaeological dig, very easy to miss.

Lovely. Fascinating post as always!

Thanks Julian (excellent book on Joseph Merceron, fascinating reading)

What a splendidly creative way to preserve the finds made in that archaeological dig ~ layers unpeeled, indeed. No wonder you were moved to philosophize. I do have one mundane question, though, prompted by what’s above ground: Are those chess pieces part of a special installation?

Hi Geraldine – as far as I could tell they were there to play with. If they were part of an art installation it was very difficult to see (although so many of them are !!)

Playthings. That’s even better!

I always relished a visit to the cathedral, back in the day. That skin-&-bone effigy of Thomas Cure freaked me out, as a memento mori should do. But the boss of the devil ingesting Judas always made me grin. And I could never walk through the retro choir without imagining the sounds & smells of the horses when the Parliamentarians used it as a stable.

I do hope you get to Holland Park this year!

Yes, Holland Park is on the list. I found a lovely book titled “Holland House in Kensington” published in 1967 in a second hand bookshop last year – a fascinating place.

That would be the book by Derek Hudson I recommended to you. Glad you found a copy! The photo it includes of bomb-damaged Holland House is inexpressibly sad, given what had been there since 1607.

An interesting read thank you. I was brought here while searching for the history of a book I have owned for some thirty years. It is a small pocket bible, printed in French, that I picked up at a jumble sale as a boy. The book was published in 1855, and has a small label in the back which states: “Watkins Binder, Gravel Lane, Southwark”. Turns out this was a bible book maker, which later moved South to Cowan Street (also now gone) before closing down in 1977. The business grew from timber-clad buildings in Gravel Lane (from a drawing I found on the British Museum website) in the 1850s to a factory producing a million books a year, and employing 400 people.

Thank you for filling in another piece of the puzzle and enabling me to picture where my book came from.

One change I’ve noticed, is that the building on the left which has a shop front, has acquired a passageway in your photo. The ‘Ltd’ sign over the shop is still there albeit painted over. Do you know anything about why the passageway appeared?