As well as London, my father took lots of photos around the country during the late 1940s / early 1950s whilst youth hosteling with friends from National Service. Long term readers of the blog will know that I am also visiting the locations of these photos with occasional trips out of London, and for this week’s post I am returning to the City of Ely in Cambridgeshire, to visit Ely Cathedral, and a historic house.

This was last August, but it seems a very long time ago now.

My father’s photos were taken on the 23rd July 1952, my photos 67 years later on the 12th August 2019.

Ely is a fascinating city, both from a historical aspect, but also the location of the city. Built on the highest point (around 20 metres) where an area of Kimmeridge Clay provides elevation above the surrounding Fens, which through their marshy and waterlogged landscape, turned Ely almost into an island.

The marsh has been drained, however the magnificent Ely Cathedral still rises over the surrounding landscape, giving the building the name of the Ship of the Fens.

Approaching the cathedral from the west provides a view of the magnificent west tower, standing 215 feet tall. The lower two thirds of the tower date from the 12th century, with the upper section being added in the 14th century. The view in 1952:

The same view today:

In the foreground in both photos is a cannon. This is a Russian cannon captured during the Crimean war and was presented to Ely in 1860 by Queen Victoria to mark the creation of the Ely Volunteer Rifles.

The walls of an old building can just be seen to the right of the above photos. This is the Old Bishop’s Palace building:

1952 above and 2019 below. I suspect that is the same tree to the left of the photo showing 67 years growth.

The Old Bishop’s Palace dates from 1486 when it was built by John Alcock. It was the home of the Bishop’s of Ely from 1486 to 1941, when it was taken over by the British Red Cross. The building is now part of King’s Ely public school.

Ely has seen its fair share or religious persecution over the centuries. During the reign of the Catholic Queen Mary I, her attempts to reverse the English reformation and restore the Catholic church resulted in two Protestant martyrs being burnt to death on the green outside the cathedral and Old Bishops Palace.

William Wolsey and Robert Pygot were both from the local town of Wisbech. Wolsey was accused of not attending Mass and also of possessing and reading a smuggled New Testament in English. Pygot was accused of not attending church. They were both burnt at the stake on the 16th October 1555.

Wolsey was almost looking forward to his fate. Foxe’s Book of Martyrs records that in the days preceding his execution “that being wonderful sore tormented in the prison with the toothache, he feared nothing more than that he should depart before the day of execution (which he called his glad day) were come.”

During their execution, copies of the English New Testament were also burnt, and Foxe records that “With that cometh one to the fire with a great sheet knit full of books to burn, like as they had been New Testaments. ‘Oh,’ said Wolsey, ‘give me one of them;’ and Pygot desired another; both of them clapping them close to their breasts, saying Psalm cvi., desiring all the people to say Amen; and so received the fire most thankfully.”

Elizabeth I followed Queen Mary and the country returned on the reformation path of Protestantism. It was now the turn of Catholics to be prosecuted and between 1577 and 1597 the Old Bishops Palace was used as a prison for “Catholic Recusants” – those who remained loyal to the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church. Thirty two recusants were held in the Palace buildings between the years 1588 and 1597 during the reign of Elizabeth I.

Fortunately Ely is a far more peaceful place today.

The street that runs in front of the main entrance to the cathedral has the unusual name of “The Gallery”. I will visit the cathedral later, but to find the location of more of my father’s photos, I turned right along The Gallery, and walked alongside the buildings that are currently the home of the Bishop of Ely.

This was the view looking back towards the cathedral in 1952:

The same view in 2019:

Further back along The Gallery, and here to the right we can see the external structure of the Octagon, one of the magnificent internal features of Ely Cathedral.

The same view in 2019:

Along the cathedral side of the street, The Gallery has the Bishop’s residence, the external wall of a walled garden, and at the end of The Gallery is the gatehouse shown in the photo below. At the end of The Gallery, the street joins Back Hill which then descends to the River Great Ouse. The downwards slope of the street away from the cathedral down towards the river helps demonstrate that the cathedral was built on higher ground in a low lying region.

The Gatehouse today:

The Gatehouse leads into Cherry Hill Park, an open space which includes Ely Castle Mound, the site of a long demolished castle. The park also provides a walkway down to the river, with superb views of the southern facing side of the cathedral.

There is another historic building in Ely which my father photographed in 1952. Oliver Cromwell, who led Parliament’s forces to victory during the Civil War and led the country as Lord Protector during the period of the Commonwealth, lived in Ely between 1636 and 1646.

This was Oliver Cromwell’s house in 1952:

The same house in 2019:

Cromwell inherited the house along with a number of other properties in Ely from his uncle. He was firstly the MP for Huntingdon, then from 1640 the MP for Cambridge, and raising troops to defend Cambridge was one of his first actions at the start of the civil War, including a number of soldiers from Ely.

The building today has a Tourist Information Office and also has a Civil War Exhibition. The building also hosts Murder Mystery evenings and an Escape Room – all the commercial things that historic buildings without large numbers of visitors need to do to survive.

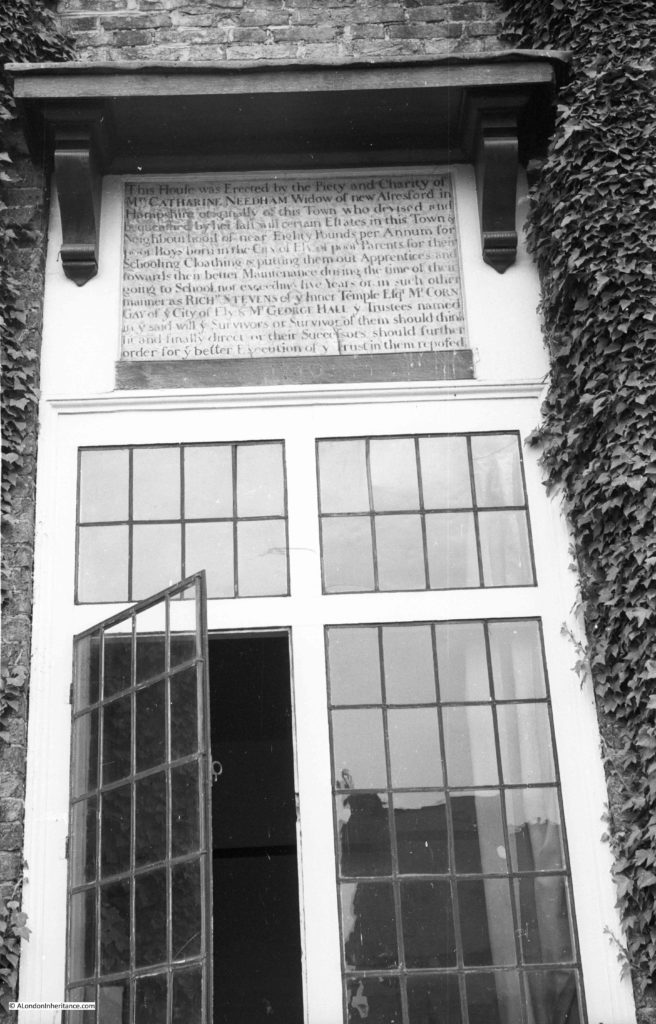

I could not find the location of the following photo:

We walked around all the buildings that look as if they would have such a window, but could not find the location. I suspect it is within the King’s Ely school.

The inscription tells that the house was erected by the piety and charity of Mrs Catherine Needham, Widow of New Alresford in Hampshire, but originally of Ely. She left certain estates in the town and neighbourhood of nearly eighty pounds per annum, to be used for poor boys born in the City of Ely of poor parents. For their school clothing and putting them out as apprentices.

Having had a walk around the town, the next stop was to visit the inside of Ely cathedral.

Ely Cathedral occupies a site with a long religious history – from a time when the area occupied by the town was surrounded by marsh and water.

Originally, a monastery founded by Etheldreda, an Anglo-Saxon queen in 673, was built on the site of Ely Cathedral. The site was probably the location of an earlier religious building.

Etheldreda reached Ely after fleeing from her husband, the King of Northumberland. The Isle of Ely was part of her wedding dowry.

The monastery was a mixed community of both monks and nuns.

Etheldreda would be viewed as one of the more important English saints, compared with St Cuthbert, and Thomas Becket. Bede portrayed her as an English version of the Virgin Mary.

After her death, she was buried in the monastery, and her body was believed to be incorruptible.

In the 10th century, Ethelwold, the Bishop of Winchester converted Ely into a Benedictine Monastery, and the Isle of Ely was defined by King Edgar as a Liberty and therefore free of royal interference.

The next name from history to pass through Ely was Hereward the Wake, an Anglo Saxon noblemen and one of the rebels against the Norman Conquest who assembled in Ely in 1071. William the Conqueror sent a force which surrounded Ely. There are various legends as to how Ely was taken, that the Norman’s built a causeway over the marshy land, that they bribed a monk to show them a safe route into the town or that the majority of the would be rebels negotiated. However Ely was taken, Hereward the Wake apparently disappeared into the marshes, and again become a figure of legend, possibly being pardoned by William, hiding in Scotland or being ambushed and killed by Norman knights.

Building of a new Norman cathedral that would replace the Anglo-Saxon monastery could now commence, and this was started in 1082 by Simeon who was the brother of the Bishop of Winchester. Work on the new cathedral was slow and gradual, with the style changing over the years as new Bishop’s took over and new design approaches were tried.

Bishop Ridel was appointed in 1169 and completed work on the Gothic west front. The church had a Norman central tower, however in the early 14th century this would collapse leading to one of the most beautiful features of the cathedral we see today, being constructed in its place.

This was the central Octagon which required far more substantial foundations than those that supported the Norman tower, so parts of the central church were demolished to create a large space for the Octagon supporting structure to be built, and foundations were dug down to a depth of 3m. At the very top of the Octagon is a magnificent lantern.

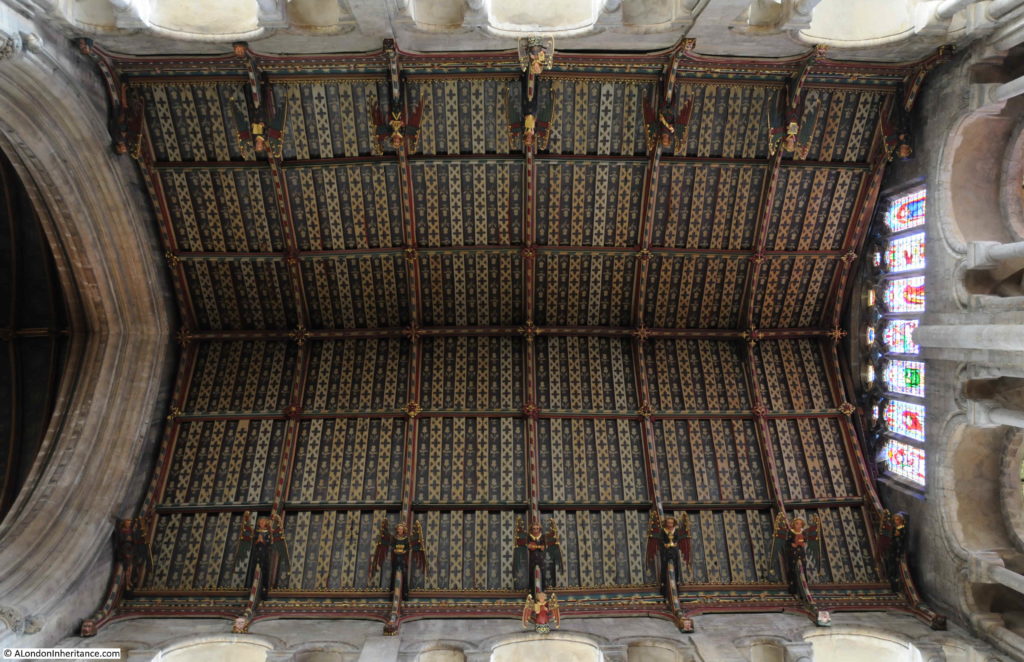

The view of the nave after entering Ely Cathedral:

The painted roof was part of the Victorian restorations of the cathedral, and is the work of two artists, Henry Styleman Le Strange and Thomas Gambier Parry, who painted the final six of the panels – you can see the change of style halfway along the roof.

Underneath the Octagon – a magnificent example of medieval architecture and construction.

Occupying the space of the collapsed central Norman Tower, the pillars were moved further out to enlarge the central space, and were built on much firmer foundations.

The Octagon is topped by a central Lantern and is built of wood covered in lead to reduce weight, as a stone lantern would have been too heavy for the pillars to support.

The height of the Octagon is 142 feet, and was the work of Alan of Walsingham. John of Burwell carved the central image of Christ and in total, the Octagon took 18 years to complete.

Close-up view of the lantern:

The space directly underneath the Octagon is occupied by an octagonal altar:

The Octagon and Nave viewed from the Choir:

View towards the north transept and the choir:

Mid fifteenth century hammer beam roof with flying angels of the south transept:

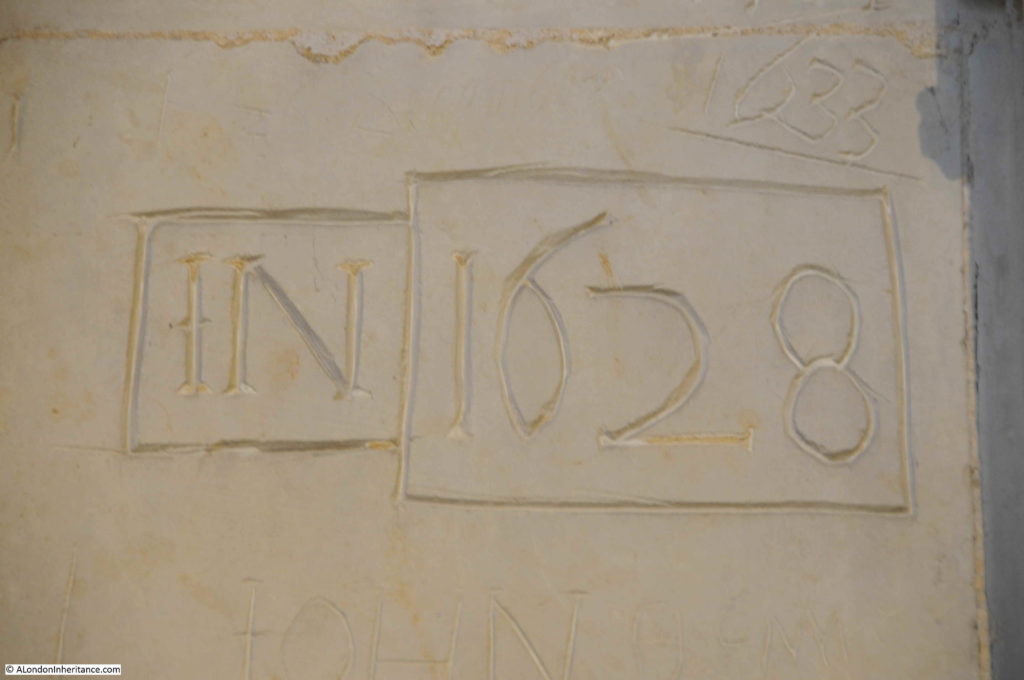

There is a remarkable amount of graffiti across the cathedral. If this happened today we would condemn such an activity, but graffiti from the past is often preserved and studied. Does make you wonder who IN was and what he was doing in Ely Cathedral in 1628 (assuming they are the initials of a person).

The remains of the canopy of a stone tomb. An information panel states that these have been mistaken as part of the Shrine of St Etheldreda. The Shrine was destroyed during the Dissolution of the Monasteries during the reign of King Henry VIII.

A plaque set into the floor marks the spot where the Shrine of St Etherdreda was located:

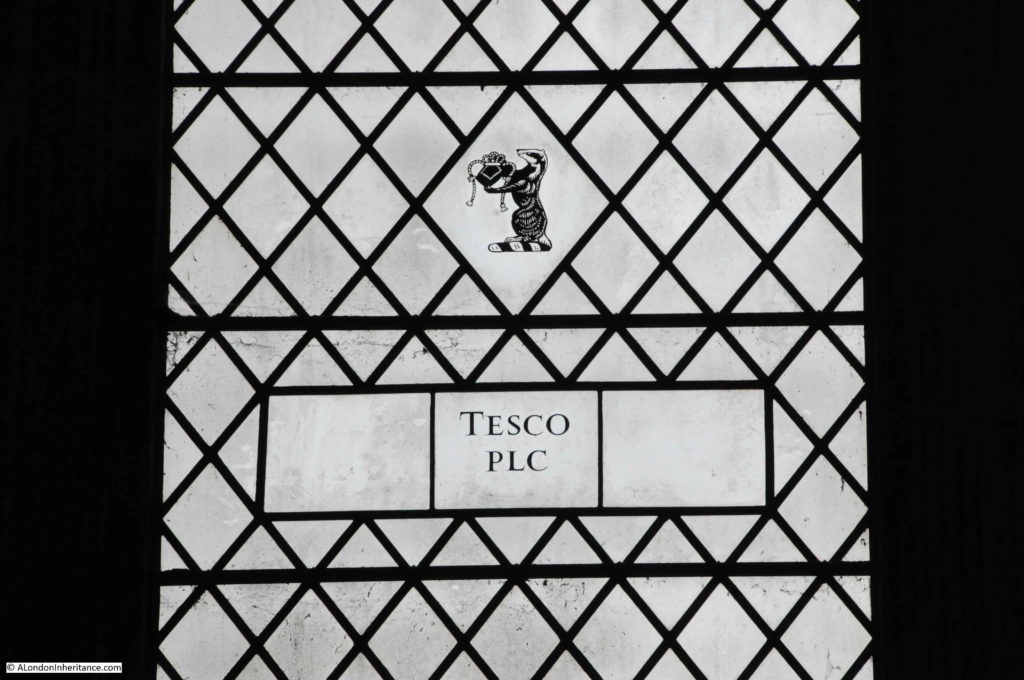

The Lady Chapel includes unusual additions to the windows. The names of companies that have contributed to the cathedral.

There is the base of a wayside Saxon cross in the Cathedral, oldest of all the monuments. It was found in the nearby village of Haddenham and the Latin inscription on the base reads “Give, O God, to Ovin your light and rest”. Ovin was apparently a common Saxon name.

I have only just scratched the surface of the history, architecture and story of this wonderful city. The Cathedral is stunning. As you approach Ely, the cathedral rises up above the surrounding landscape, and must have been even more dominant during the medieval period.

Walking the side streets reveals many more historic buildings. The River Great Ouse has played a part in Ely’s history and the drainage of the surrounding marshland which has transformed Ely from the Isle of Ely, to the city we see today. I doubt Hereward the Wake would recongise the landscape if he could return.

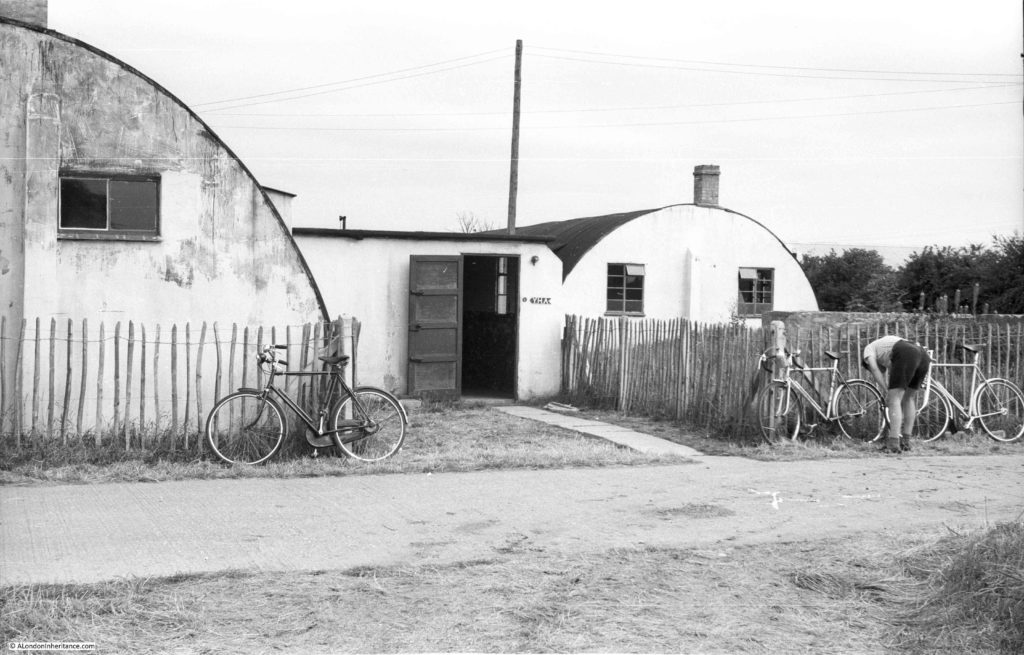

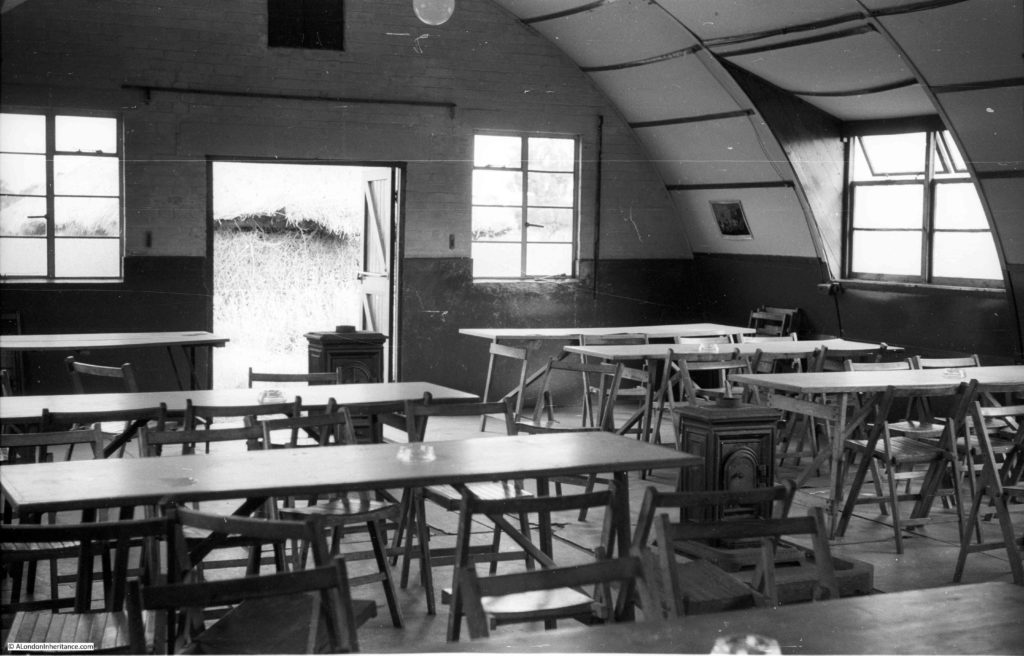

After a long walk around the city, we returned home. After his visit in July 1952, my father headed to Ely Youth Hostel, which I suspect by today’s Youth Hostel standards, was rather basic. A long bike ride from London.

Ely Youth Hostel Dining Room.

Ely is on my list of places to return – which at the moment is getting longer every day.

Lovely photos. Went to Ely a year or so back and disappointed that the Cathedral charges for entry. Part of our heritage. Should be free.

Re Catherine Needham plaque – see https://ely.org.uk/needhams.html

Thanks Mary, we looked around Back Hill but must have missed the building.

The Catherine Needham plaque is on Back Hill: nowadays the building is called the Catherine Needham Art Centre. https://ely.org.uk/needhams.html

Very enjoyable post!

Thanks Judith, frustrating that we could not find the building despite being in the right area

Wonderful. Ely is 5 miles from the village I grew up in. Lovely to see the cathedral and streets again. Thank you for posting this.

Your thought regarding the plaque was correct; it is located within King’s School, and is called the ;Catherine Needham Art Centre’. See: https://ely.org.uk/needhams.html

Thanks Peter, will have to try a return visit to see if we can find the building.

What an incredible building ! Thank you for this – it is now on MY list also.

Hello,

The cyclist outside the Youth Hostel may be the same one as on the left of the photo of the view looking back towards the cathedral in 1952.

David.

Another fascinating stroll around some beautiful architecture. Of course, there is the connection with the Bishop of Ely’s London residence (Ely Place), where there is an RC church dedicated to St Etheldreda, not to mention the historic “Ye Old Mitre” pub. It was once one of the most influential places in London with a palace of vast grounds, something akin to an independent state.

Sorry that you missed Needham’s Foundation school. It is actually clearly seen from Back Hill. Here’s the view from Google maps as you go down Back Hill towards Station Road – https://www.google.co.uk/maps/@52.3951751,0.262534,3a,75y,105.63h,89.57t/data=!3m6!1e1!3m4!1s9pTVUnE-G_Zua8bcBVJXCA!2e0!7i13312!8i6656?hl=en-GB&authuser=0

Refreshing to see very few or no changes since your father’s visit. A rare occurrence.

Fascinating to see the old Nissen huts repurposed for a Youth Hostel. An uncle and aunt of mine began their post-war married life in one and I remember going to tea with them as a very small child and being quite fascinated by the shape and smallness of the place — rather like a hobbit house though without the charm. I seem to recall a Victoria sponge cake though how my aunt would have baked one in the primitive cooker I’m not sure.

My historian partner and I enjoy all your posts very much, but especially these contrasts between the 1950s and the present. We’re in Vancouver on the Pacific coast of Canada but come ‘home’ to England every year.

Best wishes, Ann Pearson

We stopped in Ely on our way back from a holiday many years ago but arrived too late to visit the Cathedral – now on our bucket list when we eventually return to ‘normal life’.

The graffiti initials IR could be JR, which I think is what has been carved here, as there is no letter J in Latin. As in INRI – Iesus Nazarenus, Rex Iudaeorum- Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews.

So with the date after it could mean in the year of our Lord 1628 or it could be the initials JR of the graffitiist.

Thank you for this information. I visited Ely and the places you mentioned back in 2018. I took the train from London and spent a wonderful day there exploring the Cathedral, Cromwell’s home and the town. It’s a gorgeous cathedral. Thanks for bringing back the memories.

I went to Ely many years ago I will return as soon as possible much enlightened

Thanks

I would never have expected to see a reference to Tesco, in a stained glass window inside a Cathedral.

That has to be worse than any graffiti found over the centuries.

Do they offer Clubcard points on sacremental wafers or something? Abbey Well spring water maybe?

Oliver Cromwell’s house was where I discovered that carrots were originally yellow. They had a display in the kitchen and it intrigued me. Much googling later I’ve discovered we’ve got the Dutch to blame – seems like they bred them to be orange.

I love the fens, always a sense of mystery about them, and Ely rising above. Wicken Fen (national trust) near Ely gives you a sense of what the fens might have been like in the past, with former farmland returned to marsh. I recommend Graham Swift’s great fenland novel “Waterland”, and the radio 4 drama series from a few years back called “On Mardle Fen” (now downloadable from Audible and elsewhere I’m sure), both give a great sense of the place.

It always brightens my day when I see a new post of yours, especially in the current situation, and I’m so glad you’re able to carry on writing these pieces despite not being able to get out there in person. Thank you.

What a miracle of construction work: it’s one of the few buildings that makes me cry, especially the Crossing and Chapter House.

It’s many years since I last visited Ely and this has reminded me to get there again and not to take places like this for granted – just because it is there and can always be visited! Thank you for that.

The Tesco window could be described as tawdry. And that is most apposite as the word ‘tawdry’ is from the activities that took place in the city of Ely several hundred years ago.

From Wikipedia: “The common version of Æthelthryth’s name was St. Audrey, which is the origin of the word tawdry, which derived from the fact that her admirers bought modestly concealing lace goods at an annual fair held in her name in Ely. By the 17th century, this lacework had become seen as old-fashioned, vain, or cheap and of poor quality, at a time when the Puritans of eastern England disdained ornamental dress.”

Is the Tesco window an ironic artwork on that theme? If only!

Thanks for this really interesting post. I live in Australia, and we are currently getting Tony Robinson’s series on cathedrals, so this is very timely for us. I love the way you are able to take photos in the same places as your father. Those buildings look really clean now – hard to know if they have been cleaned up or if the black and white images just make them look darker than they were. Yet another place to put on my list of places to visit, when I come to England next, whenever that may be. Stay safe!

Oliver Cromwell was married in Cripplegate church an area you covered with great skill in a previous blog well done again

David ayres