“To the Right Honourable Slingsby Bethell, Lord-Mayor. The Right Worshipful the Court of Aldermen and Sheriffs, and the Worshipful the Court of Common-Council of the City of London.

The Proprietors of this voluminous and useful work, undertaken with a pure intention to preserve those monuments of antiquity, which convey a just idea of the wisdom, good governance, loyalty, religion, industry, hospitality and charity of your predecessors in the Magistracy of this City, and to perpetuate down to the latest posterity the present flourishing and prosperous State of this Metropolis, to which is arrived by your Zeal for the Public Good, steady attachment to the true Interest of your fellow Citizens, and unwearied Application in the Support of Trade, National Credit, and Works of Charity; and by Duty and Gratitude, as well as Affection, induced to make this Public Acknowledgment of the many Obligations they owe for your kind Assistance which has enabled them to finish so extensive and chargeable a Plan, and to seek your Patronage and future Recommendation”.

So reads the dedication at the start of William Maitland’s “History and Survey of London From Its Foundation to the Present Time”.

The History and Survey was first published in 1739, with an expanded version in two volumes in 1756. Maitland was a Scottish merchant and antiquary, born around 1693 and died in 1757. He was a Fellow of the Royal Society, but not too much appears to be known about his life.

An obituary after his death in 1757 reads “At Montrose, in an advanced age, William Maitland Esq. F.R.S. author of the histories of London and Edinburgh, and one of the history and antiquities of Scotland, lately published. He was born at Brechin, and had lately returned home to spend the remainder of his days with his relations; who, it is said, have got by his death above £10,000”.

As well as Scotland, he appears to have lived in London for some years, including when he was working on the History and Survey of London.

I cannot find any reference as to how he created the work, however he references previous historians of London, and if his work on Scotland offers a comparison, he would send out letters to vicars, societies, organizations, etc. asking for their respective history and details, which he would compile.

The History and Survey of London provides a very readable history of the city, and a wealth of information about so many aspects of the city in the first half of the 18th century.

I was able to get hold of a copy of Maitland’s History and Survey of London some years ago. Two large volumes comprising 1392 pages of text and tables and numerous drawings and maps, so for today’s post, let me take you through one of the volumes of the History and Survey of London and explore London in the early 18th century through a fraction of the information Maitland offers.

The page photos are directly from the book. Due to the age of the book, the tight binding and condition of the pages, I have not straightened or flattened them out, so some of the photos may look a bit distorted.

Click on any of the pages for a larger view.

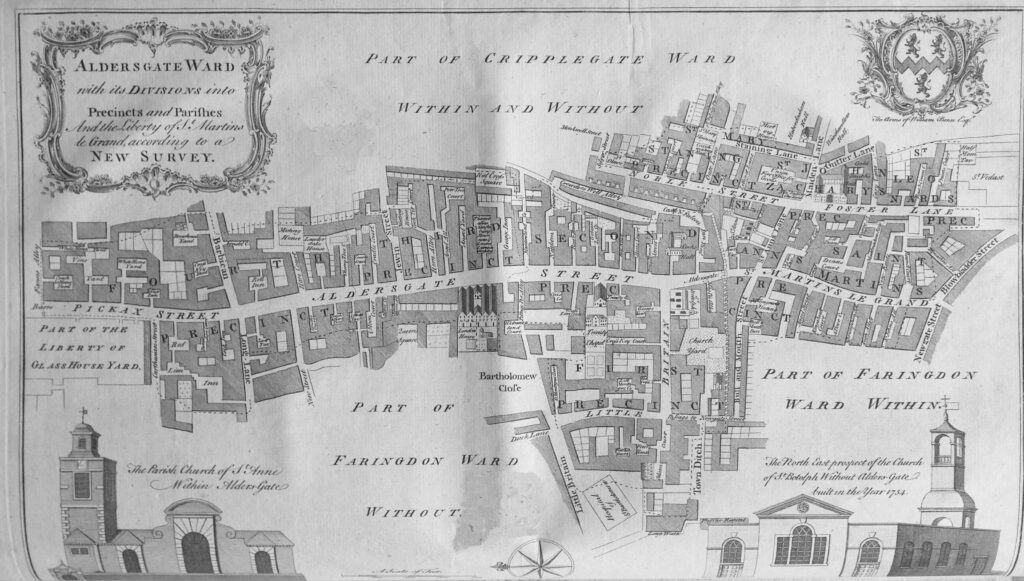

The first Ward map is of Aldersgate Ward, which “takes its name from that north gate of the City, and consists of Diverse Streets and Lanes, lying as well within the Gate and Wall, as without”.

The map shows Aldersgate Street as the central street with the “diverse streets and lanes” of the ward radiating out either side.

Interesting that north of the junction with Long Lane and Barbican (now Beech Street), Aldersgate Street was called Pickax Street.

To the right of the map is the wonderfully named Blowbladder Street, and just above is Foster Lane, the home of the Goldsmiths Hall:

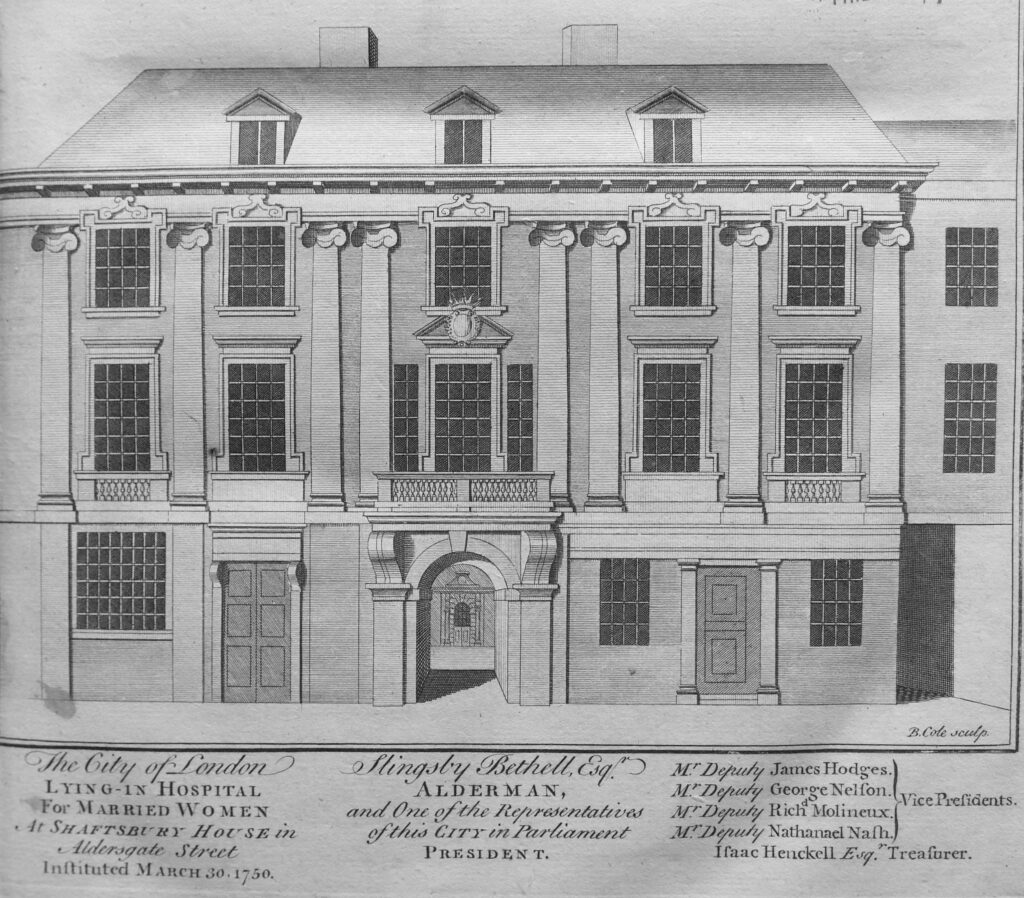

Also in Aldersgate Street was the City of London, Lying-In Hospital for Married Women, which had been “instituted on March 30th 1750”.

The description of the hospital provides a clear view of the attitudes of the time, and who was deserving of charity. The name of the hospital indicates that it was only for Married Women, and the text further includes terms such as “the industrious poor” and that it had been set-up for the “Wives of Poor Tradesmen or others labouring under the Terrors, Pains and Hazards of Childbirth”.

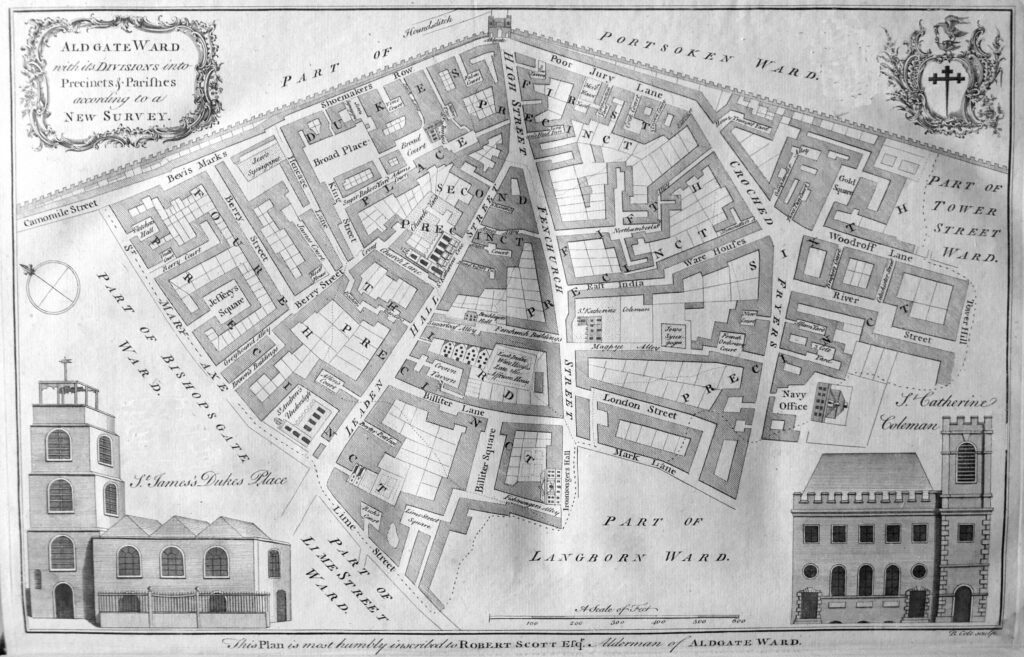

We next come to Aldgate Ward, which “takes its name from the East gate of the City, called Aldgate, or anciently Ealdgate”.

The map includes the Ironmongers Hall, the Bricklayers Hall, the synagogues off Beavis Marks and in Magpye Alley, and to the south centre of the map, the East India Warehouse.

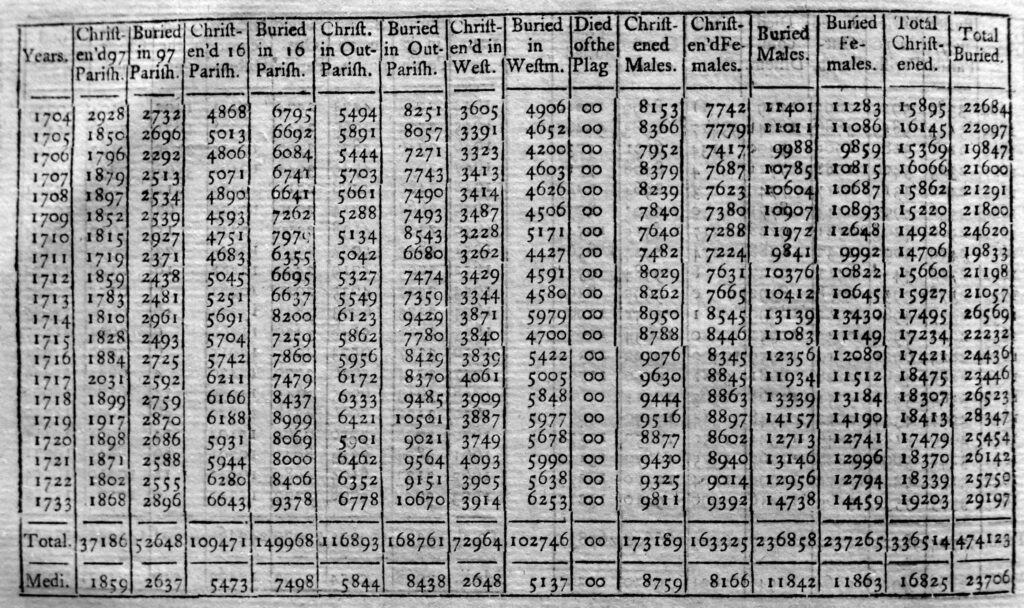

Within the dense text of the books, there are numerous tables providing statistics of life in London in the first half of the 18th century. The table below shows the number of people buried between 1704 and 1733, including where they were buried, split by male / female and those who had been christened.

As would be expected, the number of deaths changes year to year, however there is a gradually increasing trend in the total number of deaths per year which probably reflects the growing population of the city, rather than an increased rate of deaths for a given population count.

There are a wealth of statistics in the book, all begging to be entered into an Excel spreadsheet followed by a bit of graphing – perhaps one day.

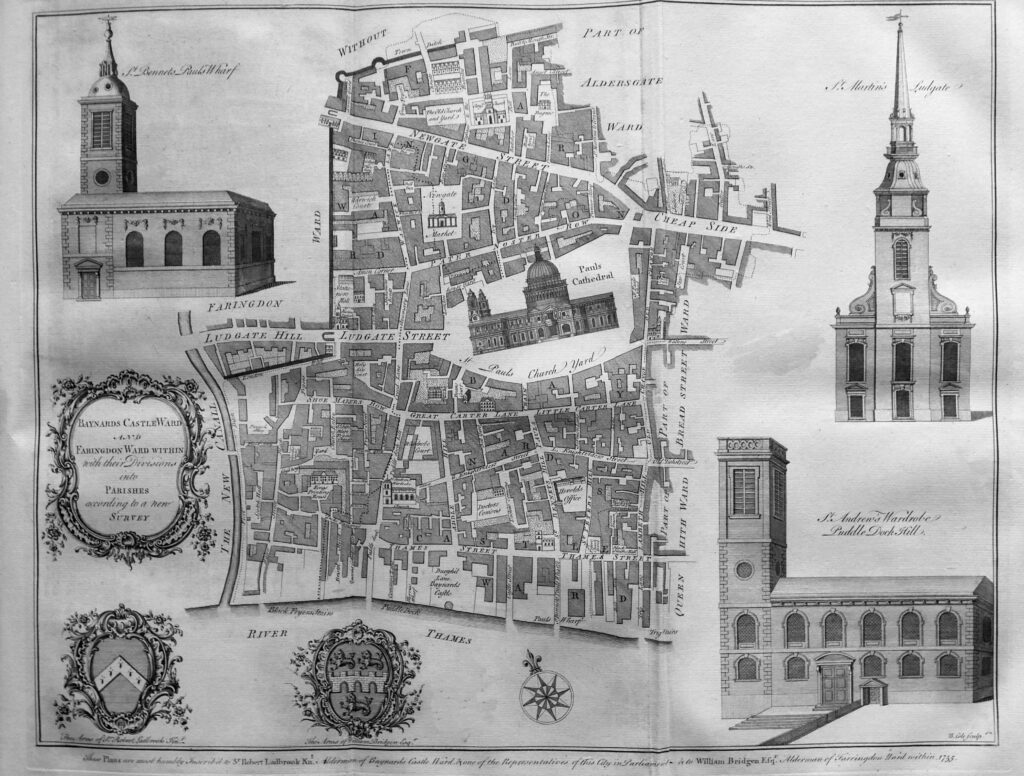

Next up is Baynards Castle Ward and Farringdon Ward Within.

The map shows the location of Barnards Castle on the river to the south of the map. Farringdon Ward is Within, as it is within the old City walls as shown by the thick line to the left of the streets, along with the Fleet River, or the New Canal.

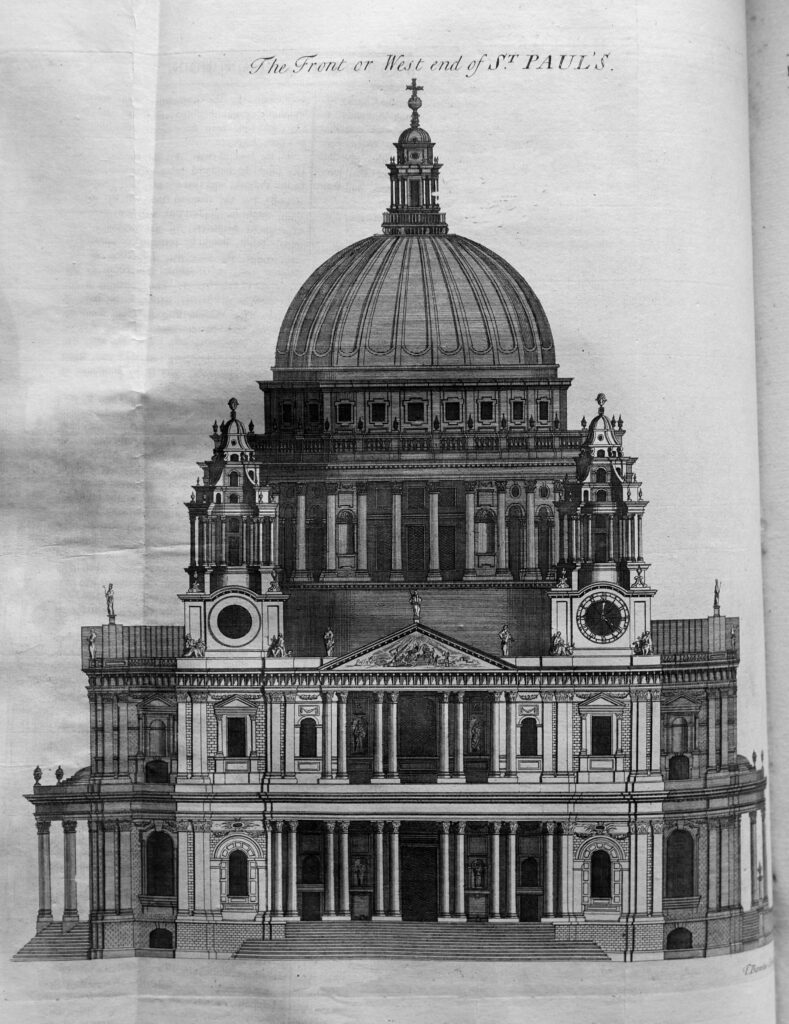

At the centre of the map is St Paul’s Cathedral, at the end of Ludgate Street (note that the present day street was divided into Ludgate Hill and Street at the location of the city gate). The book includes a print showing the west end of St Paul’s, facing onto Ludgate Street:

Very few drawings seem to get the dome of the cathedral right, and the above drawing seems to have a slightly flattened dome.

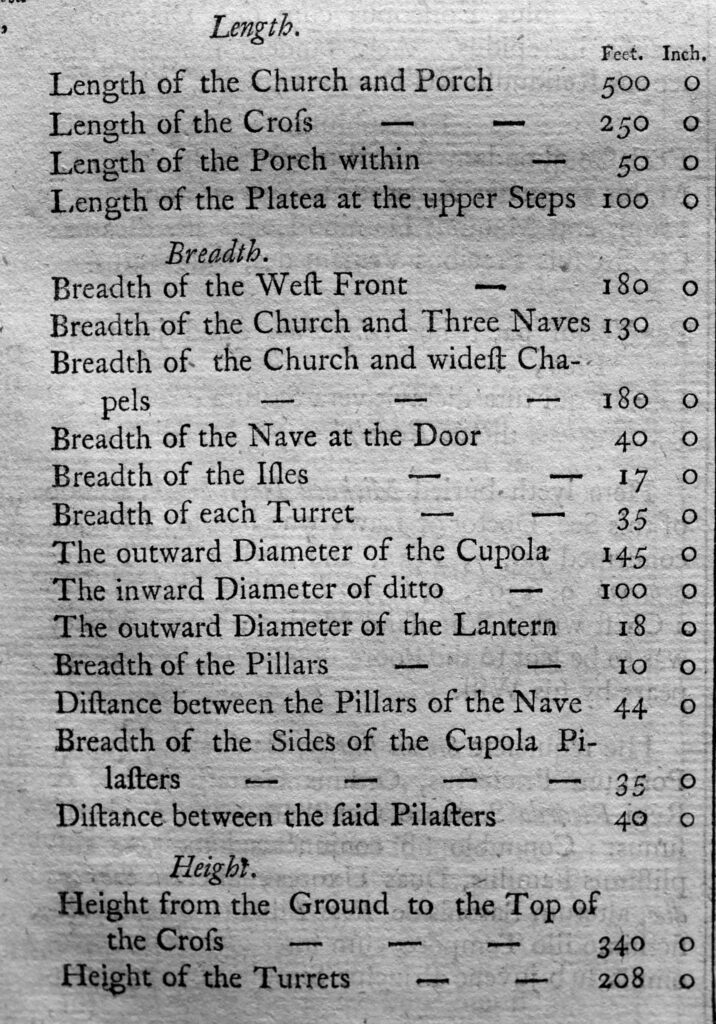

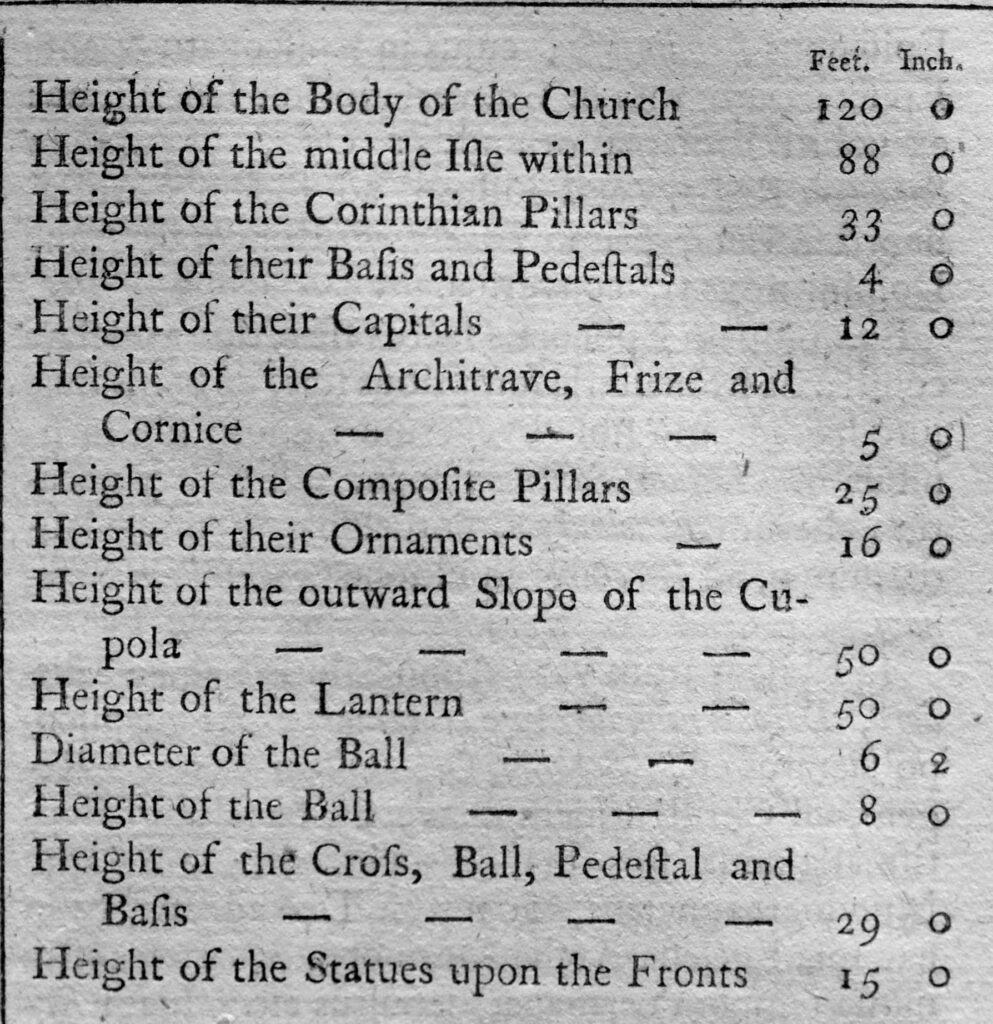

The book includes the dimensions of the cathedral, which was still relatively new at the time the book was published:

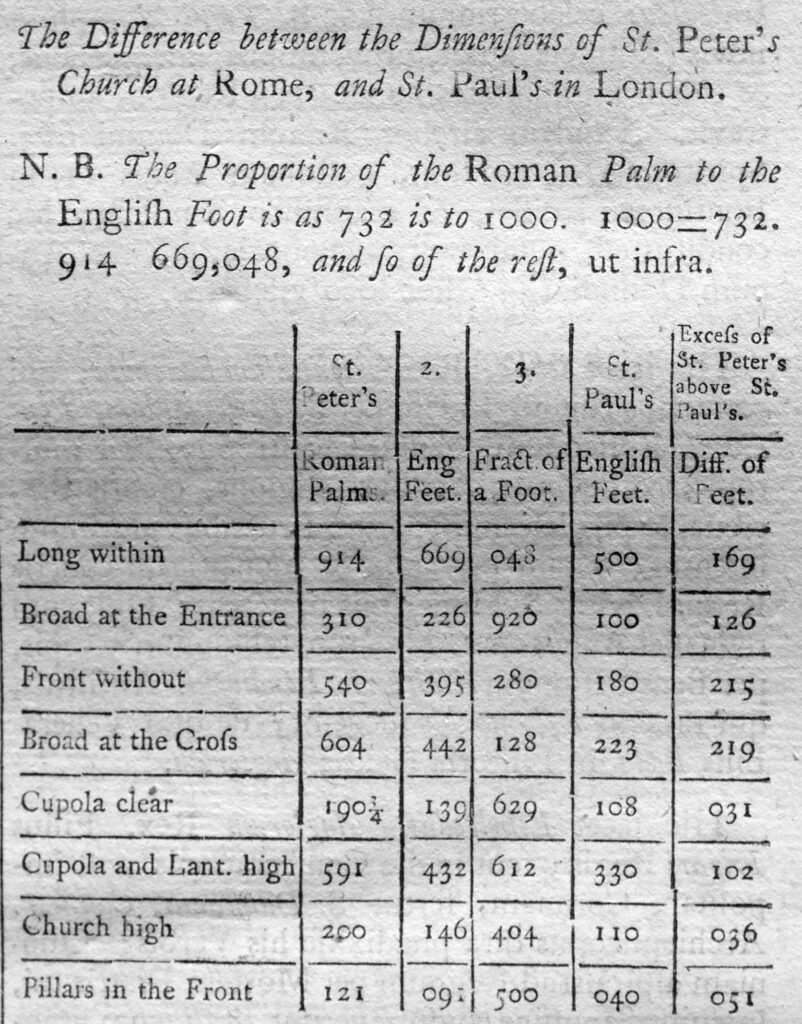

As well as the dimensions of the cathedral, there is a comparison with St Peter’s Church in Rome, where St Peter’s was apparently still measured in Roman Palm, so the table includes a conversion from Roman Palm to English Feet. The table shows that in all measurements, St Peter’s is larger than St Paul’s.

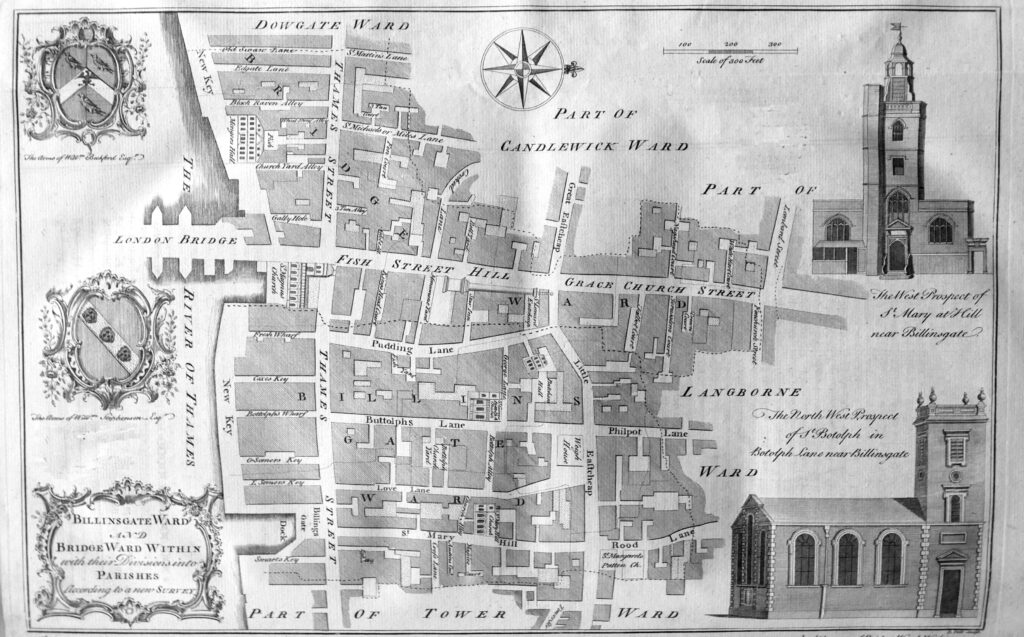

We next come to Billingsgate Ward and Bridge Ward Within.

The map shows Thames Street running the length of the ward, with the street being described as “a place of very considerable trade on account of its convenient situation near the water, the Custom House, Billingsgate and several Wharfs and Keys for the lading and unlading of Merchants Goods, and is very well built for that purpose”.

The map shows the original location of London Bridge, when Fish Street Hill and Grace Church Street were the main streets leading down from the centre of the City to the river crossing.

The text lists twenty one Keys, Wharfs and Docks that line the river between Dowgate and Tower Wards showing just how busy was this short stretch of the river.

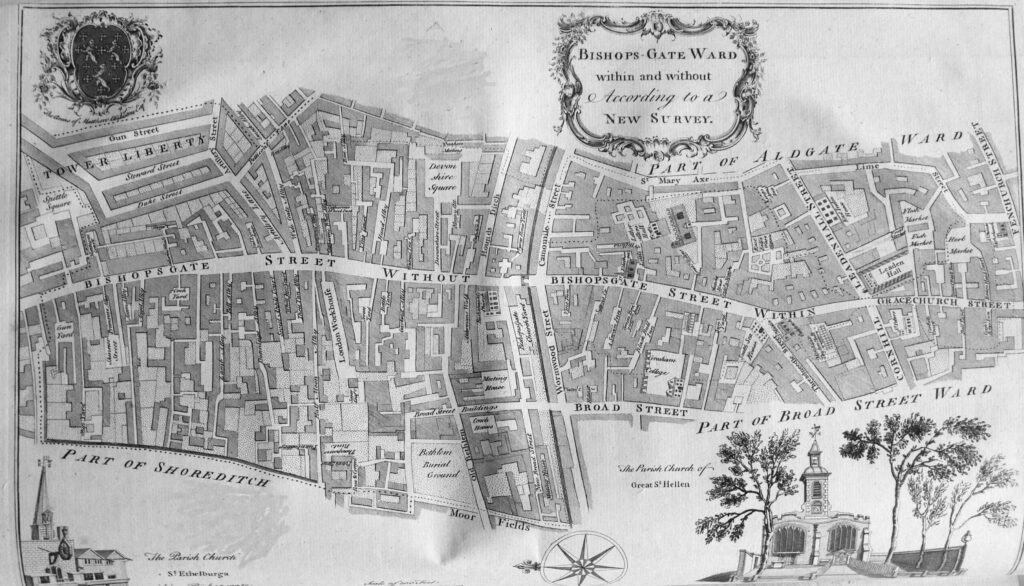

Next up is Bishops Gate Ward Within and Without, showing that the ward covered the area both within and without the old city walls.

Bishops Gate Ward was another ward that took its name from one of the City gates.

The text for each ward describes the streets and buildings of the ward, as well as administrative details covering how the ward was run. For example, for Bishops Gate Ward “There are to watch at Bishopsgate, and the several stands in the Ward, every Night, a Constable, the Beadle, and eighty watchmen, both within and without”.

The ward also had “An Alderman, two deputies, one without the Gate, another within, six Common-Council men, seven Constables, seven Scavengers, thirteen for the Wardmote Inquest, and a Beadle. it is taxed at thirteen Pounds”.

Many of these adminstrative arrangements had not changed for many centuries.

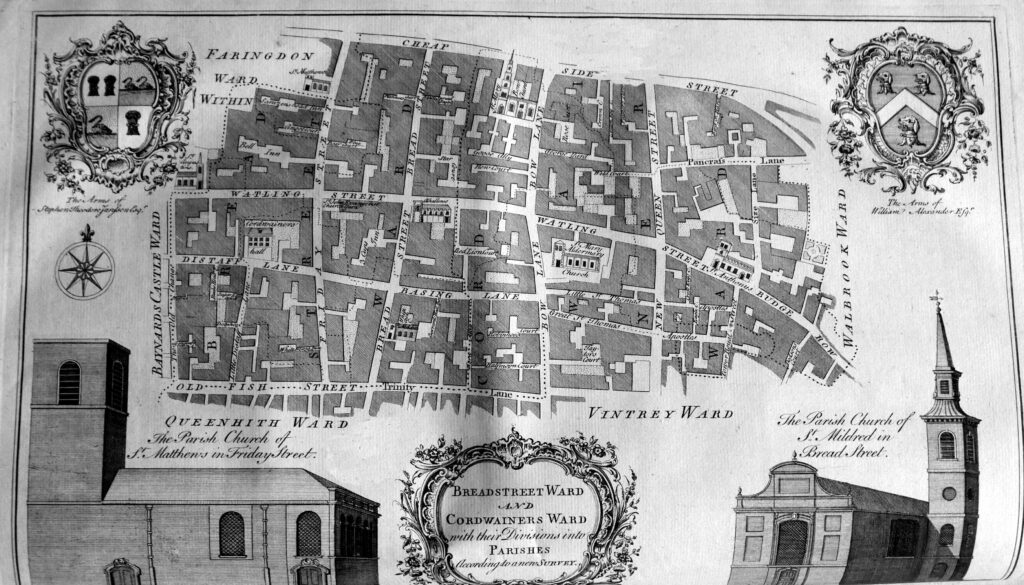

Bread Street Ward and Cordwainers Ward were two relatively small wards in the centre of the City:

Bread Street Ward “takes its name from the principal street therein, called Bread Street, which, in old Time, was the Bread-market”,

Cordwainers Ward takes its name from “the occupation of the principal inhabitants, who were Cordwainers, or Shoemakers, Curriers and other Workers of Leather”.

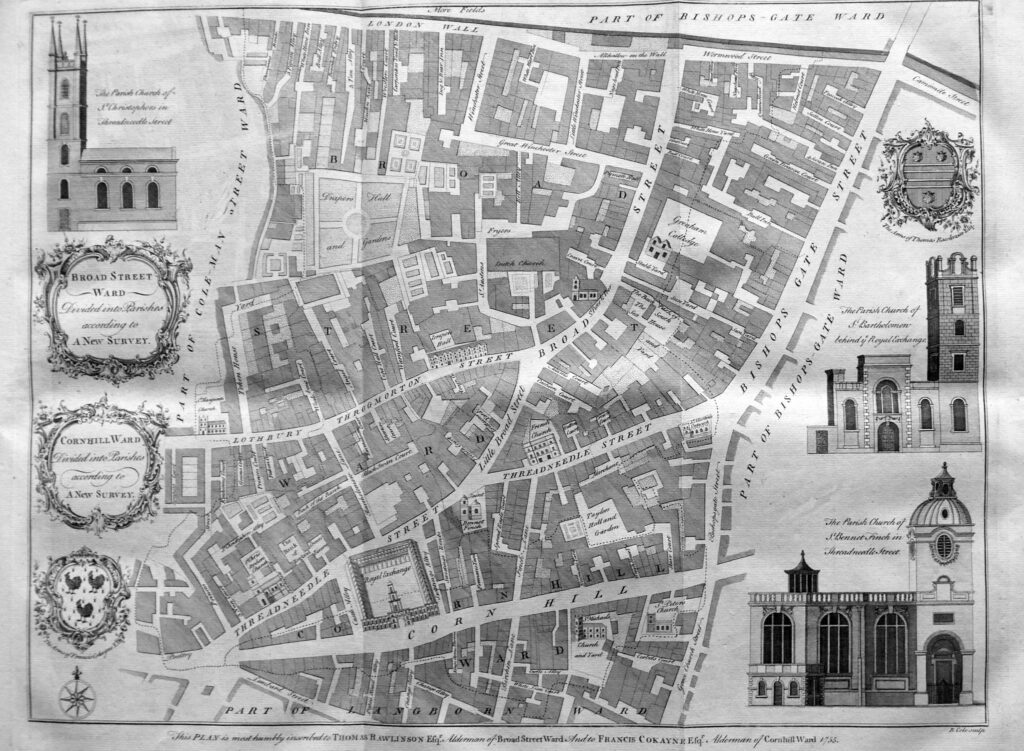

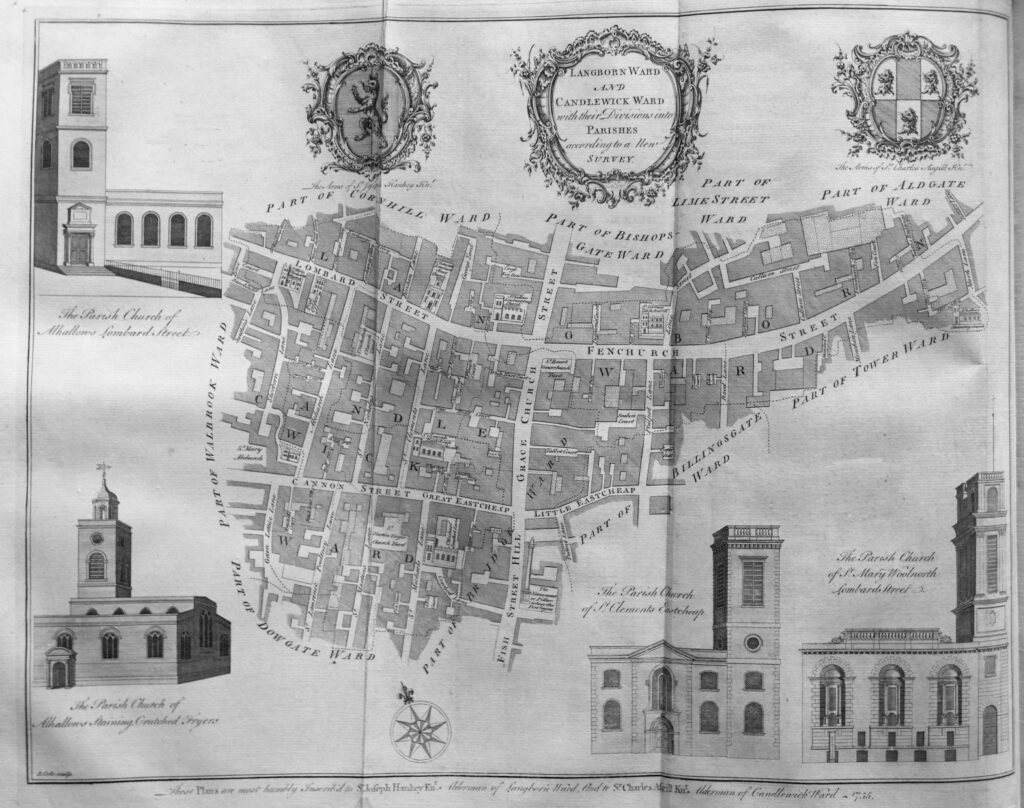

A large fold out map covers Broad Street and Cornhill Wards:

The text gives the source of the Broad Street name as being a reference to the street before the Great Fire as “there being few before the Fire of London of such a Breadth within the Walls” Cornhill Ward derives its name from Cornhill Street which took its name from the corn market which was “kept there in ancient times”.

In the lower part of the map, above Corn Hill we can see the Royal Exchange, and to the upper left of the Royal Exchange is the Bank of England, then a relatively small building. To the left of the Bank is St Christopher’s Church. This old church would be demolished in 1781 to make way for the extension of the Bank of England along Threadneedle Street as the bank expands to take up the large site it occupies today.

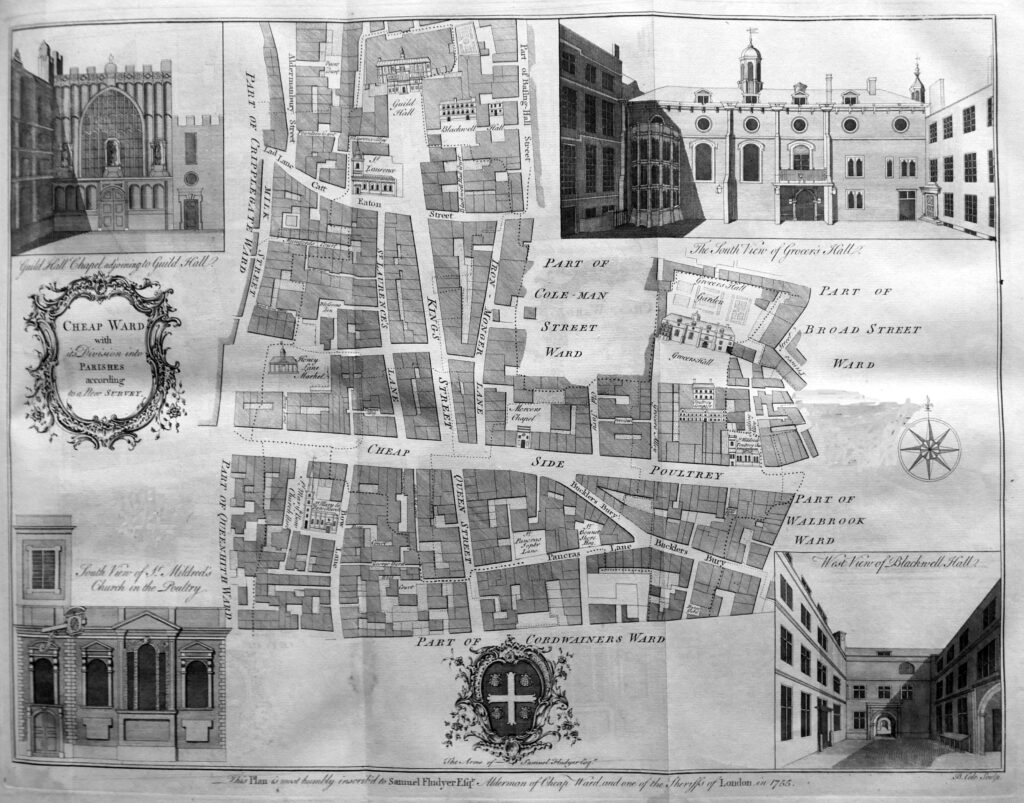

The map of Cheap Ward, includes in the corners, four of the important buildings within the ward – the Guildhall Chapel, the Grocers Hall, the Blackwell Hall and the church of St Mildred in the Poultry.

The text explains that the name Cheap comes from the Saxon word Chepe, meaning a market which was held in this area of the City. Markets and shops selling provisions have long occupied this area of the City, and on the left boundary of the ward, just above Cheap is shown Honey Lane Market. This market is described “as well served every Week, on Mondays, Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays, with provisions. The Place being taken up by this Market is spacious, being in length, from East to West 193 feet, and from North to South, 97 feet. In the middle is a large and square Market-house standing on pillars with rooms over it, and a Bell Tower in the middle. There are in the Market 135 standing stalls for Butchers, with Racks to shelter them from the injury of the weather, and also several stalls for Fruiterers”.

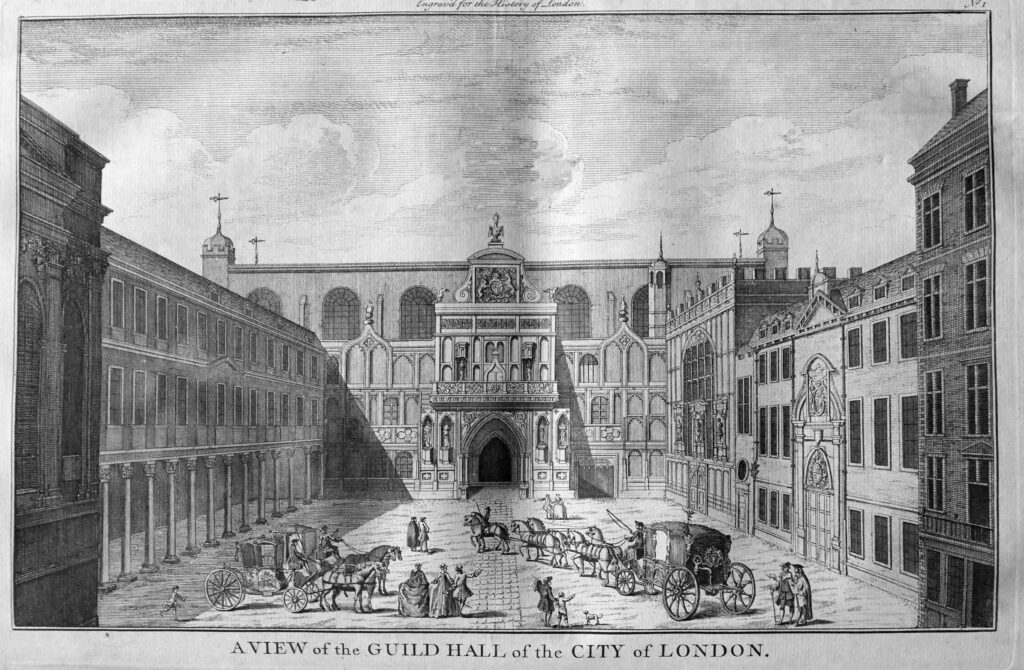

Running vertically along the map is Queen Street, then King’s Street, which run up to the Guild Hall. The book includes a print of the Guild Hall as it appeared in the middle of the 18th century:

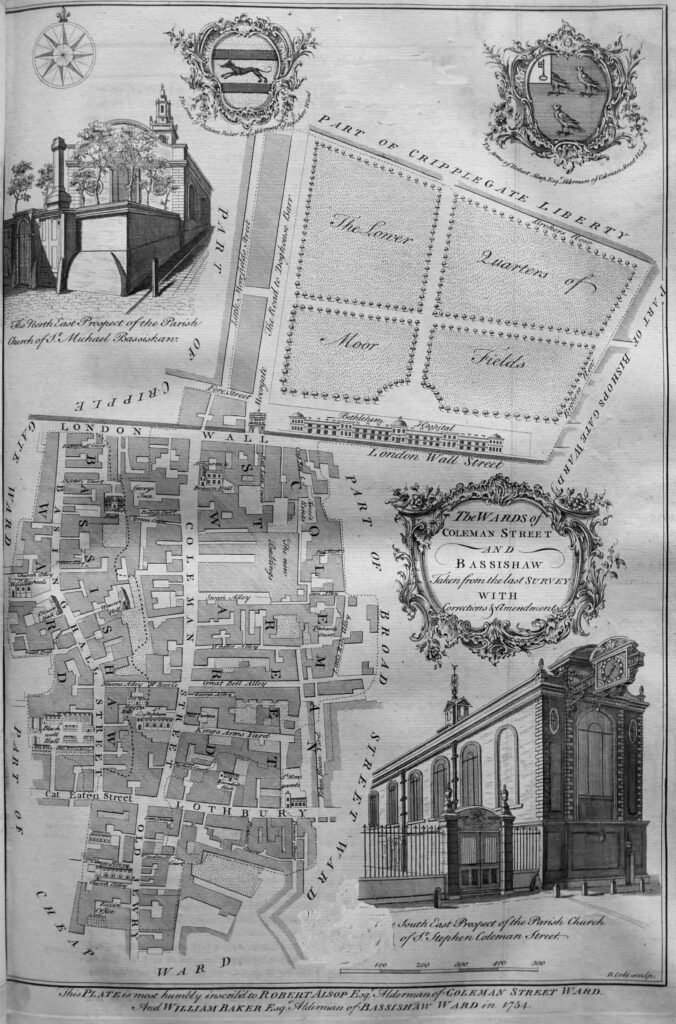

The next map covers Coleman Street and Bassishaw Wards:

The map shows the streets of Coleman Street Ward to the south of London Wall, and on the other side of the wall we see “The lower quarters of Moor Fields” and the Bethlehem Hospital.

The Moor gate leads into Fore Street and also to the intriguingly named “Road to Doghouse Barr”.

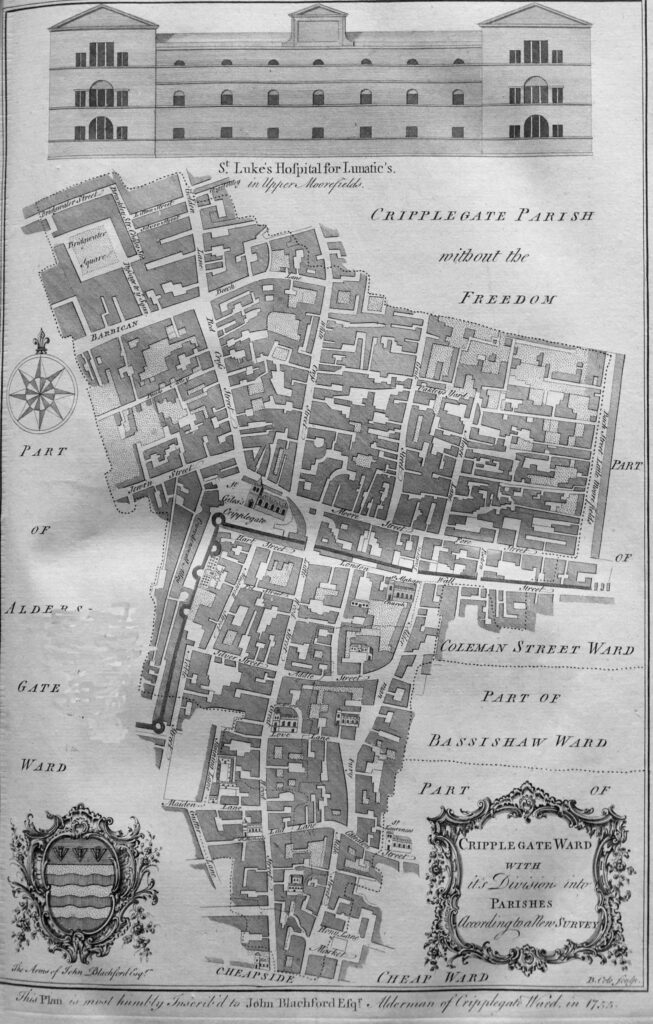

To the left of the above map is Cripplegate Ward, and it is to Cripplegate Ward and Cripplegate Parish without the Freedom that we come to next:

The map shows the ward within the well defined old City wall, with the street London Wall following its original alignment before post war reconstruction diverted the street south and removed the relationship between street and wall.

The bastions we can still see today are along the west of the ward, and outside the ward to the north is the church of St Giles Cripplegate and with further north, the streets that today are buried under the Barbican and Golden Lane estates.

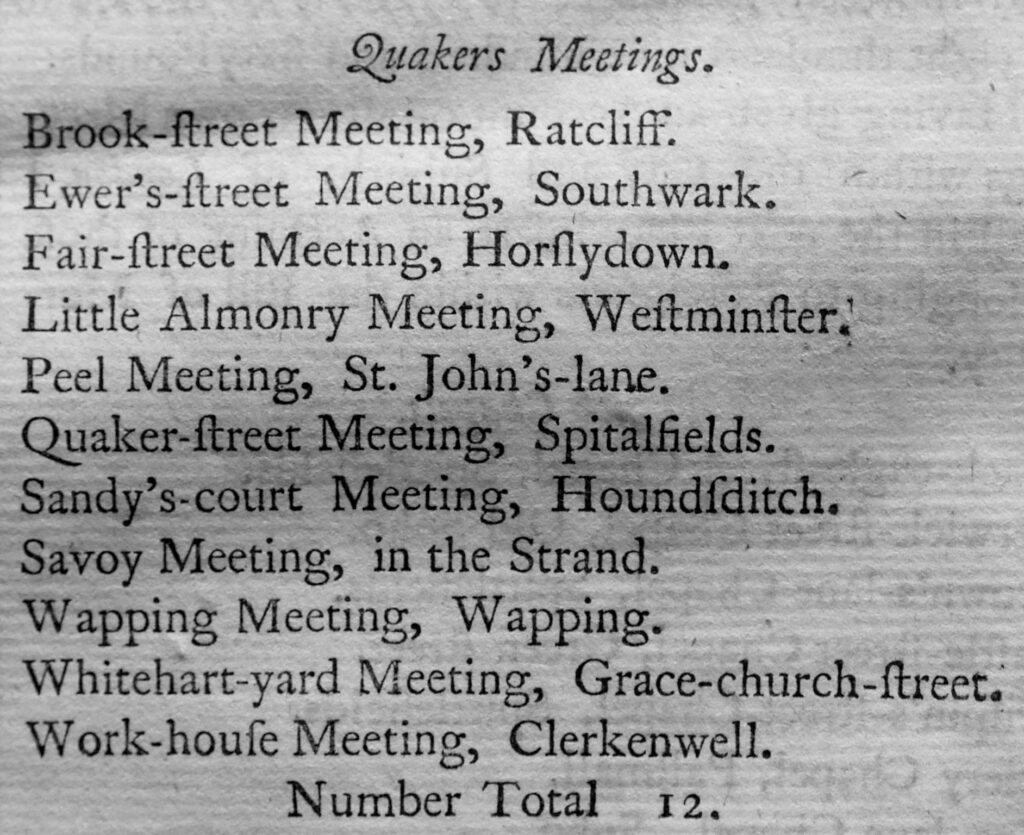

Churches are a feature of all the ward maps, and the book include long lists of all the religious establishments in London in the middle of the 18th century. The shortest list is that covering the location of Quaker meeting places, there being a total number of 12 within London at the time.

The maps also show the main Halls of the most important Guilds and Company’s of the City, the Barbers Hall is shown up against the wall to the left of the Cripplegate map. The text of the book provides details of all the Guilds, Company’s and Fellowships of the City and their order of precedence. There are a number of interesting institutions lower down in the order of precedence.

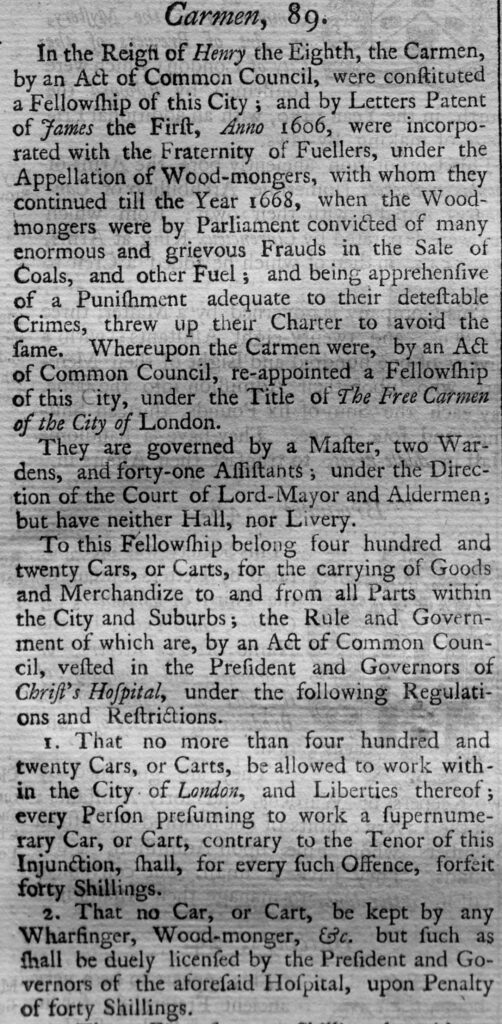

In last week’s post on St John’s Lane, the role of Carman was listed as the profession of a number of those living in the street. In the book, and at number 89, is the Fellowship of Carmen, constituted as a Fellowship of the City in the reign of Henry VIII.

The text includes all the rules and regulations for each company, and one of the key roles was in regulating how many could practice the trade for which the company was responsible. This effectively established a monopoly for each trade and restricted competition by limiting the number within each trade.

For the Carmen, no more than four hundred and twenty Cars or Carts would “be allowed to work within the City of London, and the Liberties thereof”, with a forty shilling fine for exceeding this limit.

There were some very small Companies, including at number 82, the Longbow String Makers:

The Longbow String Makers were a “Company by prescription, and not by Charter; therefore may be deemed an adulterine Guild”.

An adulterine Guild was a set of traders or a profession that acted as a Guild, but without a Charter, and had to pay an annual fine for the privilege of acting as a Guild.

And in at number 91 were the Watermen (sounds more like a music chart). This profession has featured many times in my posts on the Thames and the River Stairs.

The Watermen were charged with overseeing the watermen’s trade between Gravesend and Windsor, and that those who worked as watermen followed a strict set of rules.

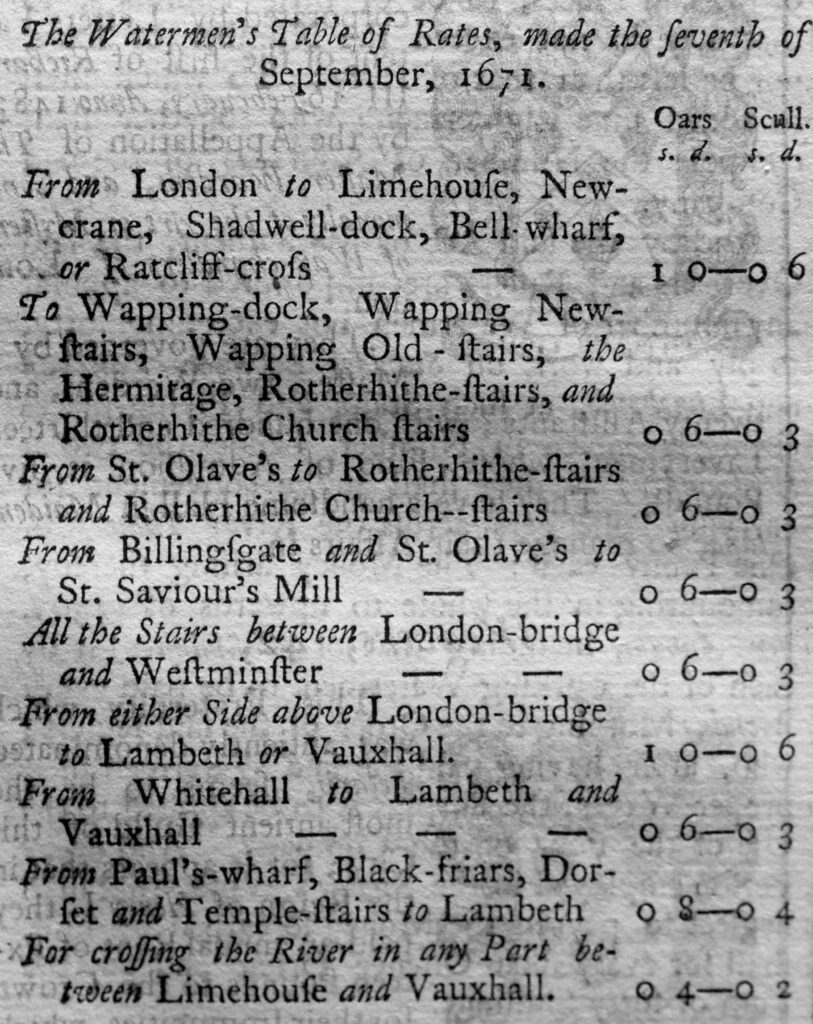

One of the rules was a Table of Rates, listing what a Waterman could charge between specific places on the river. This was important for customers as when you wanted a Waterman to transport you along the river, you would have wanted the assurance of knowing the cost, and that any of the Watermen trading at a specific boarding point should be charging the same rate.

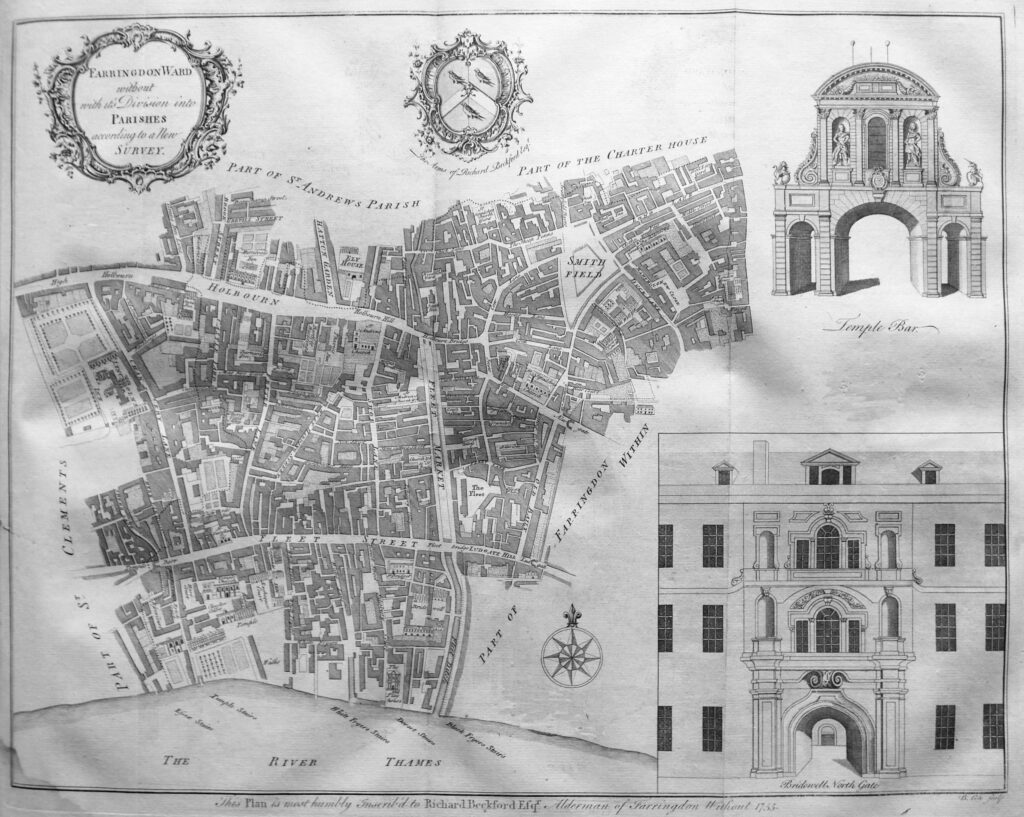

Next comes Farringdon Ward Without:

This is a large ward, and runs up to Temple Bar to the west (an image of which is in the top right corner). We have also moved into legal London with Lincoln’s Inn to upper left. In the centre of the map is the River Fleet, although now the Fleet Ditch below Fleet Street and covered by the Fleet Market between Fleet Street and Holbourn Bridge.

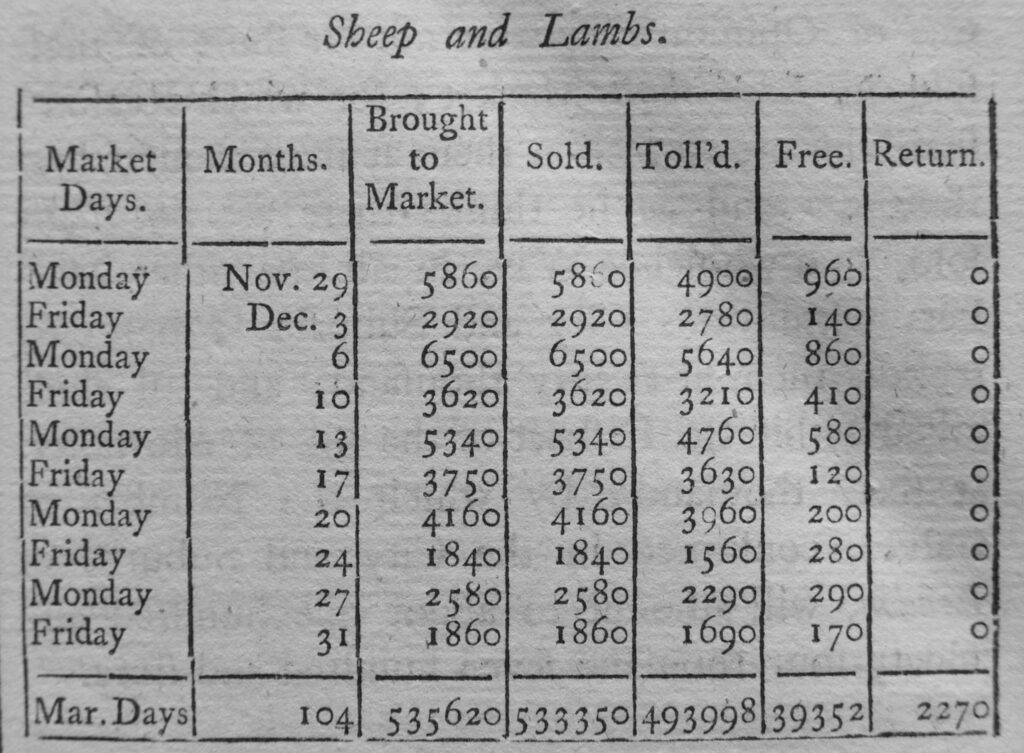

To the upper right of the map is Smithfield, and just to the right of Smithfield are “The Sheep Penns”.

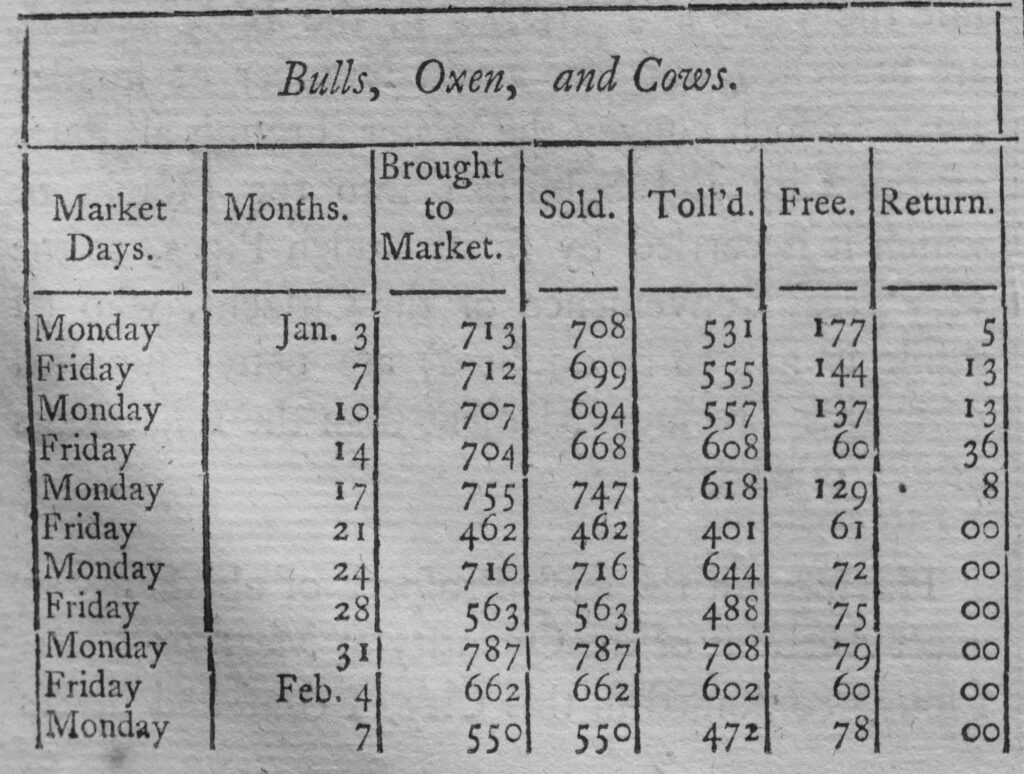

The book includes details from the Smithfield Clerk of the Market’s Account for the Year 1725 which shows the high numbers of animals sold at the market each day.

The tables are too large to include in this post, however a couple of extracts provide a sense of the numbers passing through the market in 1725:

The numbers in the bottom row of the above table show the total number of Sheep and Lambs sold during 104 market days at Smithfield Market in 1725. A considerable number, when you also consider that these animals had been driven from their farm or fields, and had come through the streets north of Smithfield to arrive at the market, which, as the upper table illustrates was also selling Bulls, Oxen and Cows.

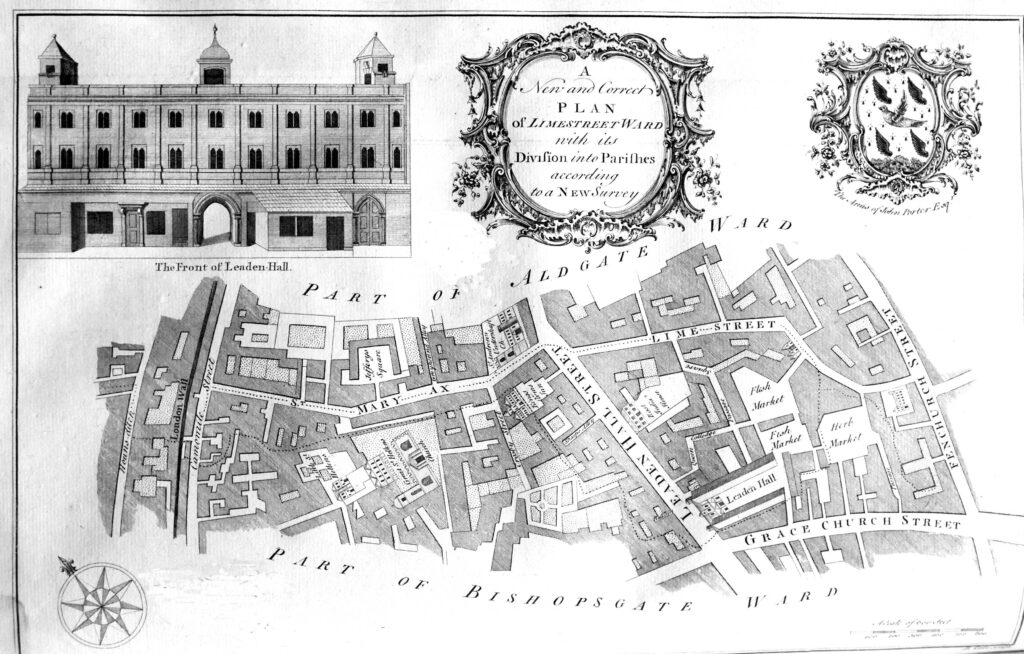

Limestreet Ward was a small ward, taking its name from Lime Street, which referred to “a Place in ancient Times where Lime was either made or sold in Public Market”.

Limestreet Ward is the location of the area now known as Leadenhall Market. The early 18th century version of the market can be seen by the references to Flesh, Fish and Herb Markets to the right of Leaden Hall Street, with the original Leaden Hall being seen to the south of the street.

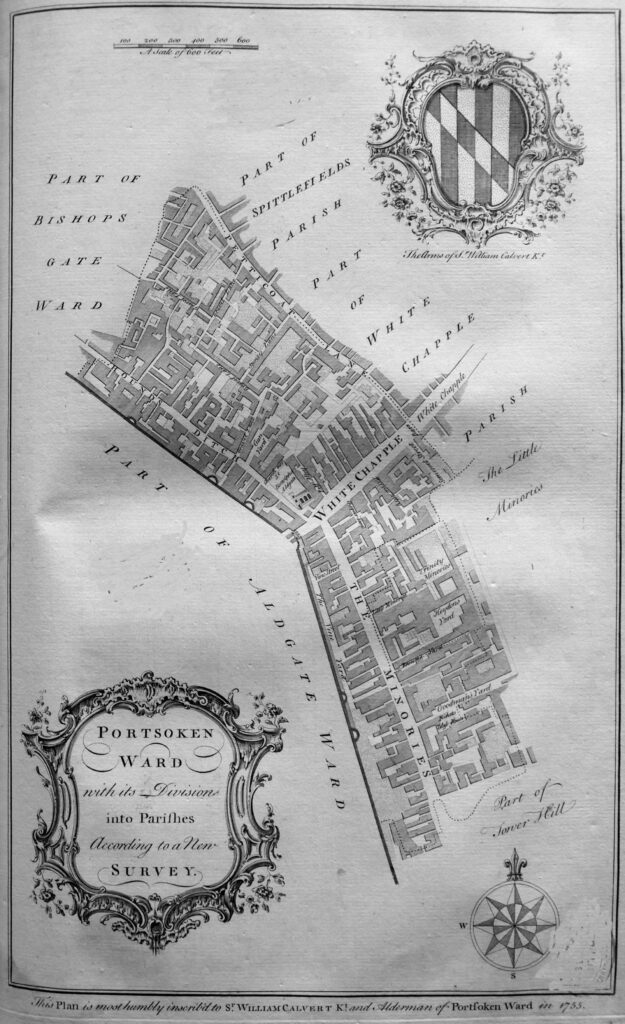

Portsoken Ward was outside the City walls.

A feature of all the ward maps is that at the bottom of the map is a dedication to an alderman of the ward. For Portsoken “this plan is most humbly inscribed to Sr. William Calvert Kt. an Alderman of Portsoken Ward in 1755”.

The description of the ward also mentions Whitechapel as the principle street to the City from the east, which was “a spacious street for entrance into the City Eastward. It is a great thorough-fare, being the Essex Road, and well resorted to, which occasions it to be well inhabited, and accommodated with good inns for the Reception of Travelers, Horses, Coaches and Wagons. Here on the south side of the street is a Hay Market three times a week”.

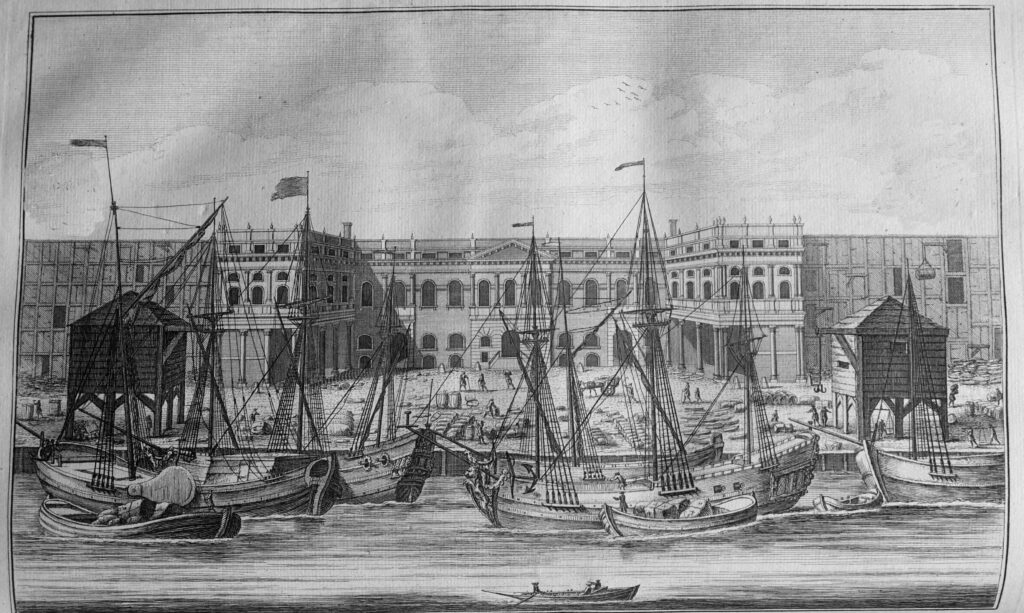

In the mid 18th century, the affluence of the City was growing based on the trade that was brought to the City along the River Thames. The river today is quiet and it is hard to imagine that the river was the hub of London business for so many centuries, and was extremely busy. The following print shows the Customs House on the river:

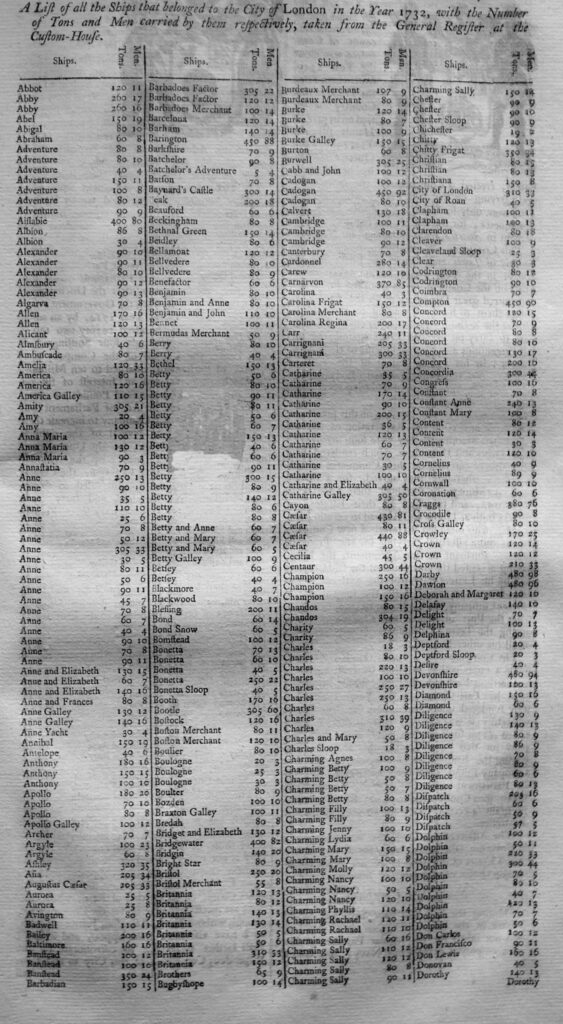

To get an idea of the scale of trade on the river, the book includes several pages of a list of “the ships that belonged to the City of London in the Year 1732”. The following is the first page of the table:

In total, in 1732, there were 1,417 ships, with a total of 178,557 tons, crewed by 21,797 men recorded as belonging to the City of London. It was these ships that transported the trade on which the City grew rich.

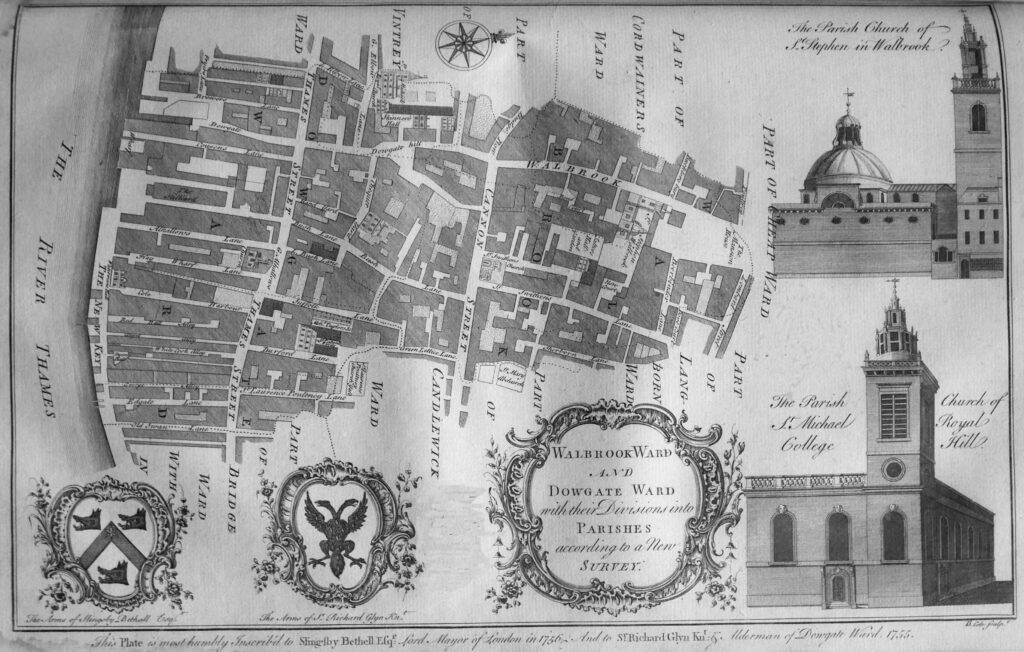

Many of those ships could have unloaded their cargo at one of the wharfs that line the river in the second of the wards in the following map of Walbrook and Dowgate Wards.

In the description of Dowgate Ward, Thames Street is described as “a great thoroughfare for carts to several wharfs, which renders it a place of considerable trade, and to be well inhabited”.

Much of that trade was run by various trading companies headquartered in the City of London. The book details all these companies, one of which was the Russia Company:

And perhaps the most well known of the trading companies – the East India Company:

The description of the East india Company provides an indication of the value of these trading companies and the wealth they created.

In 1698 the East India Company was worth Three Million, Three Hundred Thousand Pounds – a considerable sum of money at the end of the 17th century, and in the early years of the 18th century, was generating a dividend of 10%, falling to 8% for investors.

Another source of funds, part of which contributed to the City, including the costs of rebuilding St Paul’s Cathedral after the Great Fire was the Coal Duty.

A Coal-meters Office was based in Church Alley, St Dunstan’s Hill, and in the office the records of all ships entering the Port of London with coals were recorded:

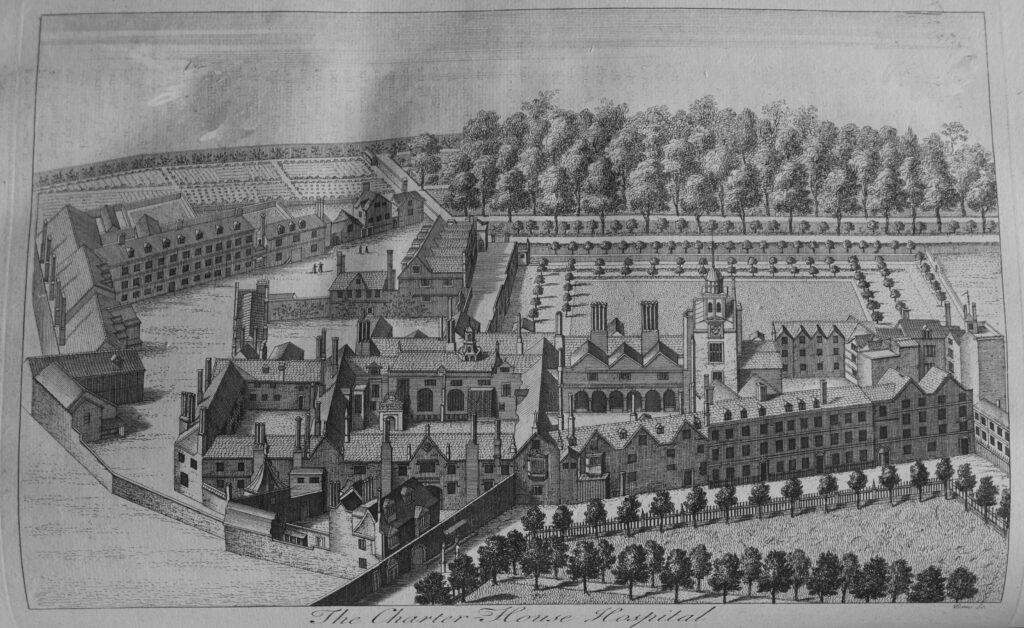

Maitland’s Survey of London included areas on the edge of, or were part of the wider London. the following print is of the Charter House Hospital as it appeared in the early 18th century:

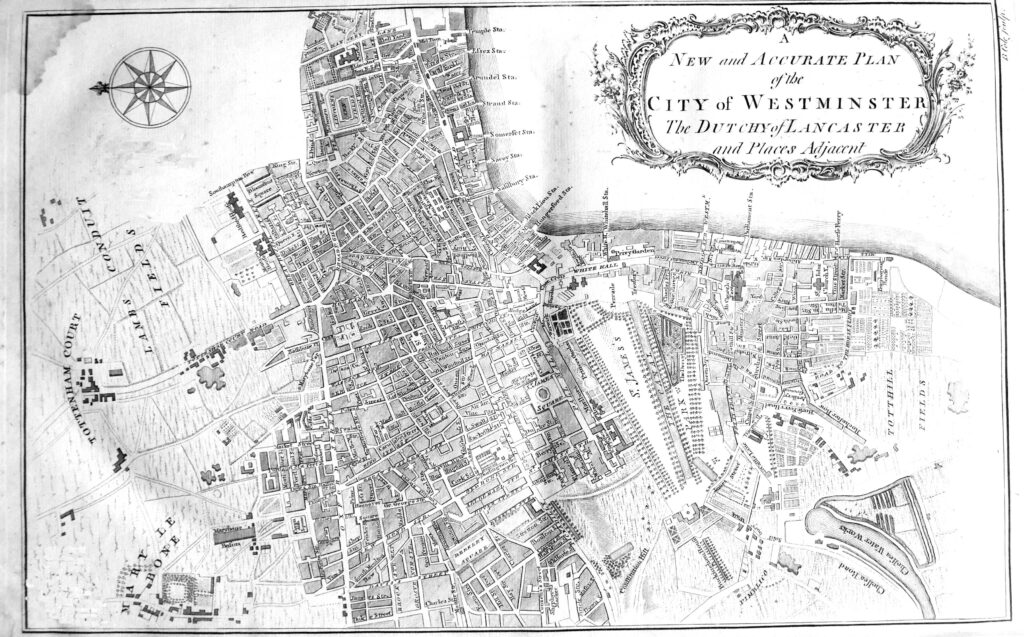

Map showing the City of Westminster and Duchy of Lancaster:

To the left of the map, Tottenham Court Road still ran through fields, Chelsea Water Works are to the right of the map, and along the river are the names of many of the Thames Stairs, all now lost under the 19th century Embankment.

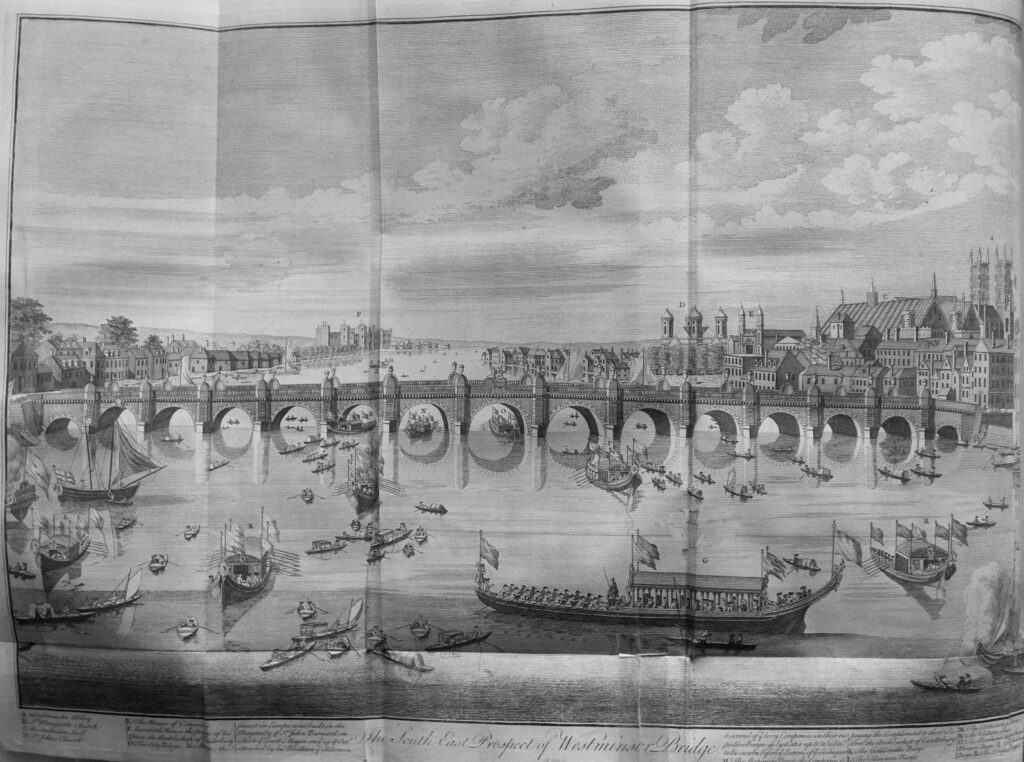

The view of the first Westminster Bridge, with the two towers of Westminster Abbey on the right edge of the print:

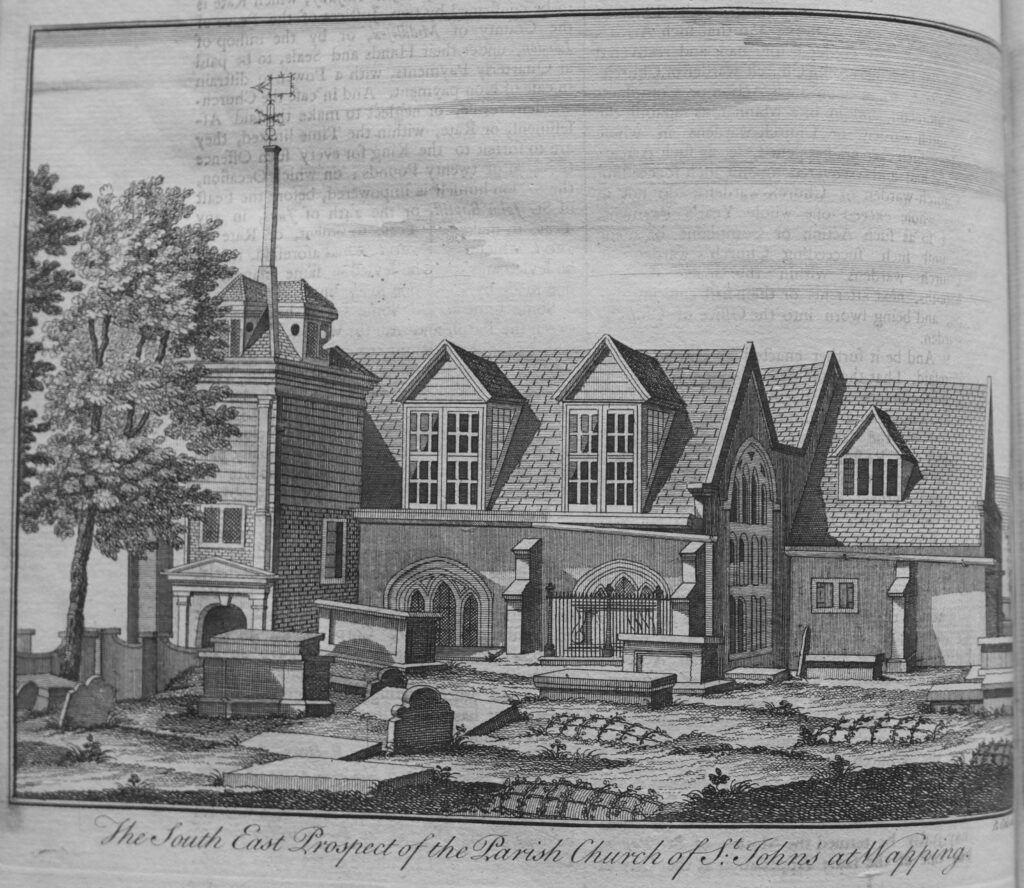

And to the east of the city, the Parish Church of St John’s at Wapping:

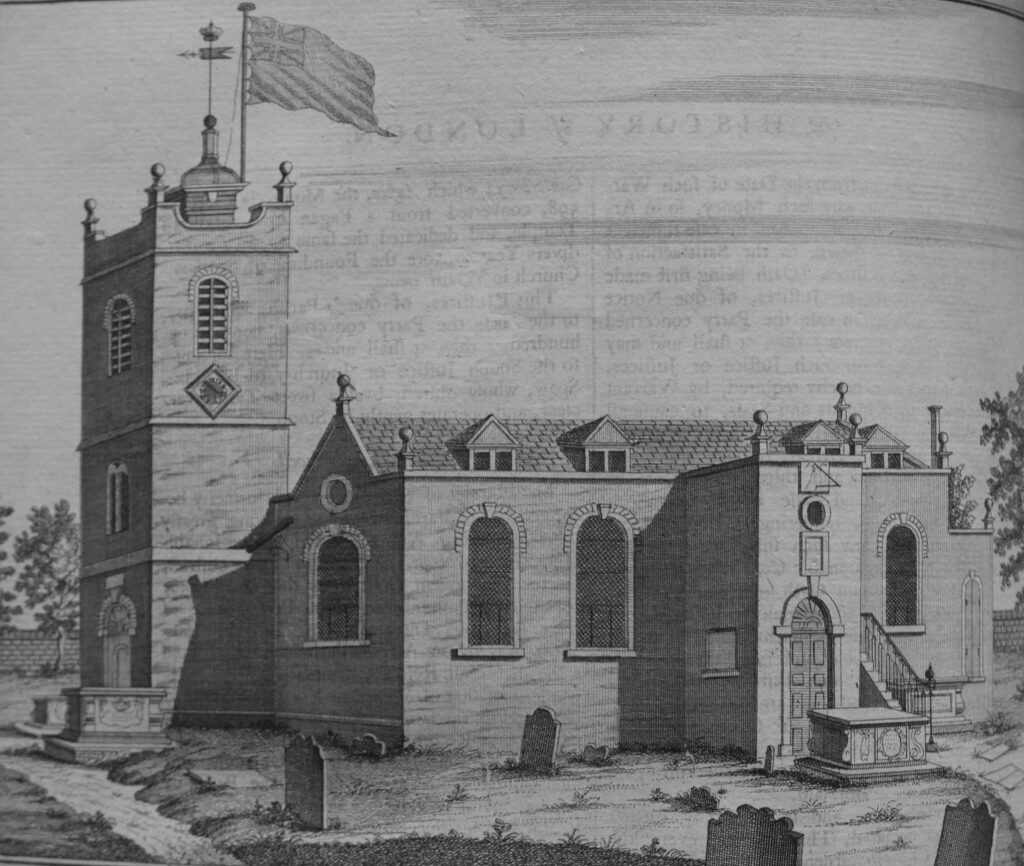

The Parish church of St Paul’s at Shadwell:

William Maitland provides a very readable history and survey of London. The book really brings to life how the city was administered and operated. The wealth of the city and the trade that generated this wealth. All manner of statistics and lists cover those living in the city, key buildings and organisations.

As written in the dedication at the start of the book, it really does describe “to the latest posterity the present flourishing and prosperous State of this Metropolis“

The History and Survey of London is also available online and can be found at here.

Dear Sir, I would like to let you know how much pleasure and joy your weekly posts bring me and to thank you most sincerely for the amazing work you do. I studied at Barr’s hospital, qualifying as a doctor in 1875. I lived in the Barbican , Lauderdale Tower for 9 years. I was married at St Bartholomew the Great in 1975. My first wife died in 2011 and I married my second wife at St John’s Gate.

I have always loved the Cuty and am a Freeman as was my father before me. Thank you so much again.

Fascinating! I was particularly nterested to read about the City of London Lying-in Hospital where my gt gt grandfather was born. The birth registers are held at the London Metropolitan Archives.

Dear William – I found your wonderful blog quite by accident while researching the kidnapping of Dr Sun Yat-sen in 1896 in London. Fascinating – and I love your father’s pictures. I too am a photographer and took some great pains to photograph street scenes in Beijing and Datong in 1986. I find your blog most inspiring and look forward to reading more! Warm regards Patrick Dransfield

If I see something about London I just have to read it. This was great to read and very informative.I have an ancestor that lived in Leadenhall Street, he was a map drawer? His name is Joseph Basire 1700’s.

What a fabulous book. Thank you so much for introducing me to it.

Thank you for a particularly fascinating blog this week. Your selection of data – such as the number of permitted Carmen, or sheep sold at Smithfield – brings to life the realities of mud-18th century London.

*mid-18th century !!

What a fabulous treat with my coffee! And a really fine piece of work, which must have taken you hours. Now I have the link saved in my bookmarks and, frankly, there goes the rest of the day. This blog is the first I turn to every Sunday and I look forward each week to seeing what you have chosen for our delight. Personally, I think you should be made a freeman of the City, and post-haste.

Absolutely fantastic So interesting. You can still recognise the streets and could almost make your way around London if you time travelled! Thank you so much.

A most interesting read. I was particularly interested in the reference to Whitechapel as that is where my earliest known paternal ancestors were living at around the time the book was published.

Another fascinating Blog.

Thanks

The dimensions for St.Pauls show a height of 340ft ground to tip of cross? When did the extra 25ft get added so that schoolchildren could always remember Wren built one foot for every day of the year?

Very interesting

Thank you !

Fascinating historical maps .thanks.

A Lovely visit back to the City of London. It brought back so many memories, enlarging the maps and walking down Memory Lane. Thank you,

fascinating article today. As ever thanks for your site.

A fascinating read, as always, thank you, and I’ve not read it all yet.

Any analysis of that table of Christenings and Burials requires caution. I’ve seen what appear to be two printing errors in two lines.

For the first year (1704), the sum of Christened 97 parish, Christened 16 parish, Christened out parish, Christened in West is 16895. The sum of Christened Males / Females is 15895, matching the Total Christened 15895 at the top right. My guess is that the first figure, 2928, should be 1928 as that is more in line with other figures in that column.

Bottom line (above the Total) should, presumably, be 1723, not 1733.

My late father had several bound issues of The Gentleman’s Magazine from the 18th Century in his library. I must read them sometime.

Fantastic read, many thanks

Thank you for yet another wonderful post. Interesting to see the bit about the Fellowship of Carmen as that was the profession listed for my grandfather on his 1906 marriage license.

A very interesting read, as ever. Keep up the good work.

Being a Carman myself, I was fascinated to see the extract about the Carmen. You may be interested to know that while the Fellowship of Carmen was established in King Henry’s reign, the status of ‘livery’ was not granted until 1848 – the only one granted during the reign of Queen Victoria. Since the extract was published a number of livery companies no longer exist (not least our arch-rivals, the Woodmongers), such that the Carmen now rank as 77th in the order of precedence. However, the Carmen now maintain a very amicable relationship with their successors – the Fuellers.