In 1953, soon after it started operation, my father took the photo below of Bankside Power Station. The photo suffers from a problem I often have when taking a photo of the southern bank of the river from the north on a clear day as the sun is in the south and puts the power station into silhouette.

In the photo, Bankside Power Station also looks only half built, which indeed it was. There is a smaller building on the left with two rows of chimneys receding from the river’s edge. This is the original power station on the site.

Roughly the same view today. The Millennium Bridge now crosses the river in front of the old Bankside Power Station building.

A view from further along the river showing the full size of the former Bankside Power Station building.

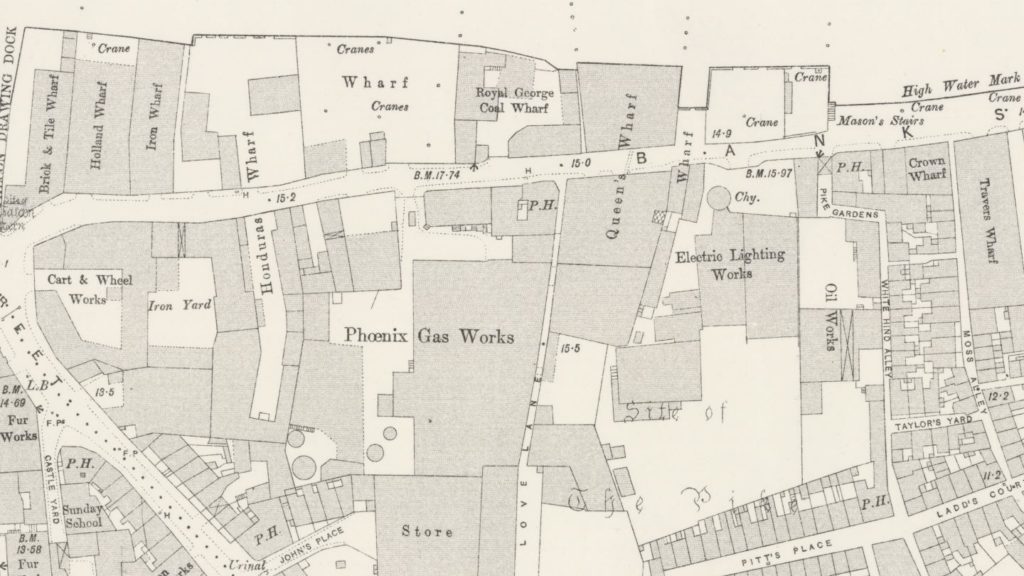

This area of Bankside has produced energy for many years before the current Bankside Power Station was built. The following extract from the 1892 Ordnance Survey map shows towards the right of the map an Electric Lighting Works and on the left the Phoenix Gas Works. Both of these industries were located adjacent to the river as they both used coal to generate either electricity or gas.

The original power station was built by the City of London Electric Lighting Company in 1891 and over the years underwent a number of extensions and upgrades to form the building with the two rows of chimneys as seen in may father’s photo.

Each chimney was connected to an individual boiler and a separate building contained the generator that was driven by the steam from the boilers to produce electricity for distribution in the local area and by cables across the river to the City. Electricity generation was originally a local activity with no national grid to distribute across the country. There were power stations located across London, including the Regent’s Park Central Station where my grandfather was superintendent.

The design of the original power station and the equipment used was highly polluting with so many chimneys pouring smoke, ash and grit onto Bankside.

Planning during the war identified the need for a significant number of new power stations across the country with post war consumption of electricity expected to surge. London would be one of the areas where the old, polluting power stations urgently needed to be replaced with cleaner power stations with higher generation capacity.

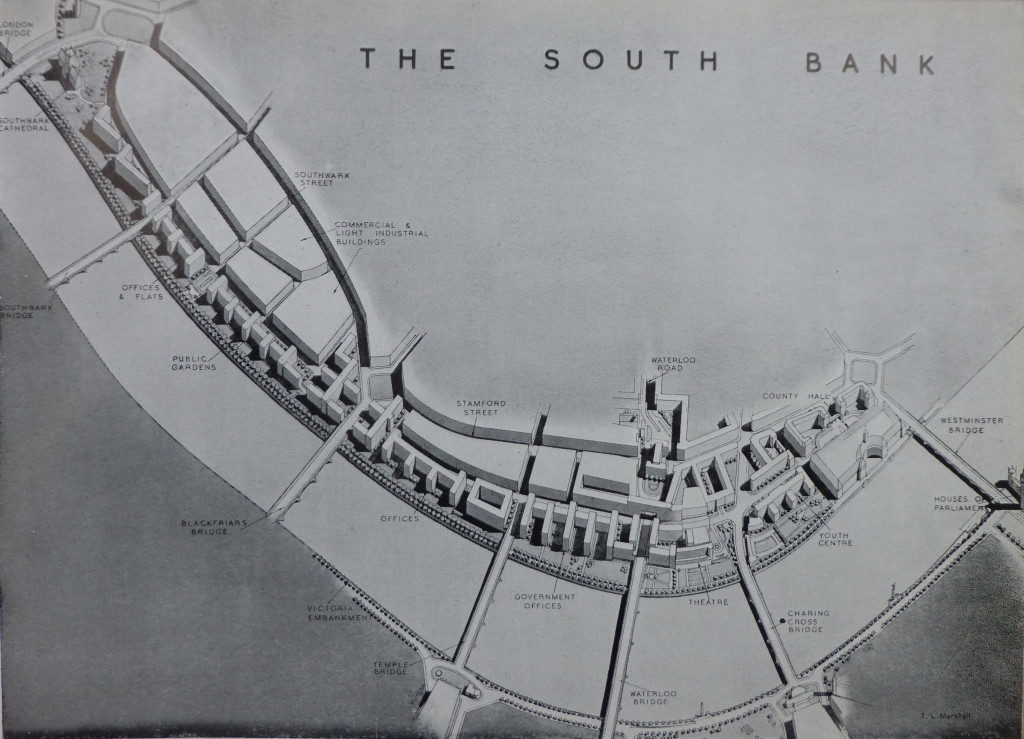

The 1943 County of London Plan proposed the redevelopment of the south bank of the river to remove heavy industry and line the river with offices, flats and public gardens with commercial and light industrial buildings to the rear. Heavy industry such as power stations were to be relocated out of central London to places such as Poplar, Rotherhithe and east along the river. The following extract from the 1943 plans shows the proposals for the south bank:

As always happens with long-term, strategic plans, events take over and problems such as power shortages during the very cold winter of 1947 forced different decisions to be made and the go ahead was given in 1947 for a new power station to be built at Bankside. In giving this approval there was one major change. Originally it was planned for the power station to continue using coal, however the level of pollution in the area, the space needed for coal storage and the need to diversify power production away from one signal source Influenced the Government to change plans for the new Bankside Power Station to switch from coal to oil. As well as being slightly less polluting, oil had the advantage that it could be stored in large underground tanks, thereby removing the need for large fuel storage areas above ground.

Although oil was slightly less polluting, the new Bankside Power Station would continue to have an impact on the local area and on the river. Flue gases were washed by water taken from the river. These waters would then be returned to the river with a higher particle content and acidic level.

When the go ahead was given for the new power station, as well as concerns about locating such an industry in central London, there were also complaints that the new building would dwarf St. Paul’s Cathedral. Sir Giles Gilbert Scott changed the design from dual chimneys to a single chimney and ensured that the overall height of the chimney was lower than the dome of the cathedral. This was helped with the land on which the cathedral is built being higher than the river side location of the power station, however the reduced height of the chimney did contribute to ongoing local pollution problems.

Construction of the first half of Bankside Power Station took place between 1947 and 1953. This saw the completion of the western half of the building and the central chimney with first power being generated in 1953, and this is the status of Bankside Power Station that my father photographed in the photo at the start of this post.

He had also walked around the area a number of years earlier when construction first started. He took the following two photos showing the demolition of the buildings that had been on the site, and the start of construction of the new power station.

In this first photo, he is standing in front of what would become the wall of the building facing to the river, at the western edge. Five chimneys on the rear of the original power station can be seen, and on the far left of the photo are the lower levels of the new chimney.

I took the following photo further away from the power station than my father’s photo above. If I was much closer it would just be looking directly into the building, however it does give a view of the same scene as it is today with the base of the chimney on the left of both photos. In the above photo it is the central core of the chimney which is seen, the brick outer structure is yet to be added.

The second photo is looking directly across the construction site towards the south.

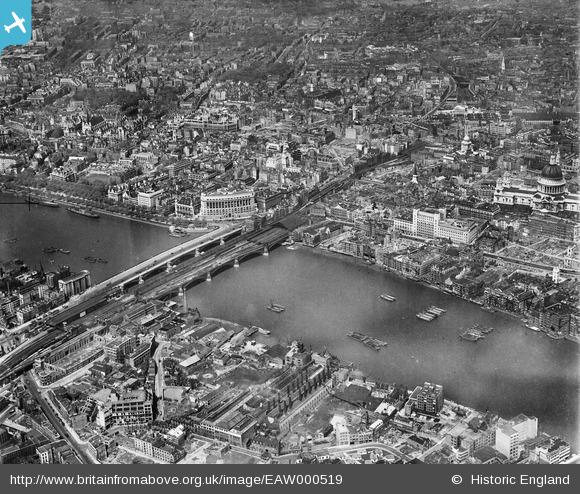

The Britain from Above website has a number of photos taken by Aerofilms which show the Bankside site under development. The first photo is from 1946 and shows the site prior to development of the new power station. The site can be located by the double row of black chimneys of the original power station which is located in the middle of the lower part of the photo.

The next photo is from 1952 and shows the power station nearing completion. The core of the chimney is complete, but it lacks the outer brick facing. The metal framework around the upper part of the chimney is the same structure as shown on the lower part of the chimney in my father’s photo. The original power station can clearly be seen covering the land where the second half of the new Bankside Power Station would later be built.

The next photo is also from 1952 and shows the power station looking from the north. This again shows the original power station to the left of the new Bankside power station.

And the final photo in June 1952, a couple of months after the above photos now shows the main building and chimney almost complete. The photo also shows the structures on the river that allowed oil tankers to dock and unload their cargoes into the underground tanks of the power station.

Both the old and new Bankside Power Stations continued in operation until 1959 when the old power station was finally decommissioned and demolished. The second half of the new power station was built between 1959 and 1963 by when the building we see today was finally in place. In all, around 4.2 million bricks were used on the external walls of the building and chimney.

The oil crisis during the 1970s had a considerable impact on the financial viability of oil fired power stations. The power station was also continuing to pollute the local area and the river. Power stations were also being built out of cities and there were now power stations further down the Thames. The continued operation of Bankside Power Station could no longer be justified and electricity generation finally ended at Bankside in 1981, almost 100 years from the first, small steps in electricity generation on the site.

The building remained unused for a number of years until plans were put in place to transform the building into Tate Modern. A competition was held for a new design which was won by the firm of Herzog & de Meuron. Their design made very few changes to the external structure of the building so the original design of Sir Giles Gilbert Scott is basically the building we see on Bankside today.

Bankside Power Station is a wonderful building. It is from an era when power stations were built as cathedrals of power, Battersea Power Station being another example of the style. The preservation of the external structure of the building and that now through Tate Modern it is fully open is to be appreciated.

Another great article – thanks. I like the map extract, amazing to see how the medieval layout of lanes had survived through to that point in time.

Fascinating – thank you for posting.

I feel partly responsible for saving the Bankside power station as I signed a petition when it was earmarked for demolition back in the 1980s. Amazing that this – and the Oxo Tower – could have been lost to the South Bank! It is interesting to compare this building to the Salvation Army college at Denmark Hill, which is another of Scott”s great contribution’s to London’s skyline.

This brought back some memories but not of Bankside. I used to be fascinated by Lot’s Road in Chelsea. My dad used to park near it when we went to Chelsea games. I was intrigued that the electricity we used might come from there. Later on in my 20s I ended up working in a coal fired power station but not in London – Chadderton power station in Greater Manchester.

What a filthy job! The coal was milled to powder so that it would ignite in mid-air as it was blasted into the furnace. The resulting ash was taken by vacuum away to a precipitation plant where it was loaded into lorries to be taken away to make breeze blocks. Some of the waste used to fall into a sluice. Sounds efficient but things used to go wrong – unblocking the precips was a nightmare. As soon as a blocked pipe was opened the room disappeared in a dense, light-blocking soup of dust (naturally we were wearing breathing gear!). We then worked by feel alone and tapping on each other arms to communicate. If the sluices under the furnaces blocked we had to go in under the furnace (after it had been allowed to cool for 48 hours!) and dig them out. It was claustrophobic and so hot we only spent 10 minutes at a time there with the soles of our boots sticking to the floor as they melted.

So how could pollution not affect the surrounding area? The London power stations must have been spreading it liberally among the local population. At least Chadderton was outside of the main built up areas of Manchester and Oldham.

I did it for 4 months before taking a 20% pay cut to go working as a teacher in a nearby school. The pay cut was irrelevant!

Fascinating. I recall the late 70s/early 80s when you could walk along what is now the South Bank area and be completely by yourself and the power station was looking lost and lonely and everything around it was being bulldozed away. Same with the Oxo building. It was quite eerie. The idea that letting the local area and inhabitants be (more) polluted was better than St Pauls being dwarfed…ah, tempus fugit.A

Another fascinating article,thank you.

Another brilliantly interesting post, thank you!

With reference to Annie’s comments regarding how deserted this stretch once was – I would suggest that the time frame could be extended to the late 1980s. You would have been lucky to have encountered more than twenty people between Shad Thames & Waterloo Bridge.

I certainly have a fondness for the old power station and I think the transformation of the site since the Tate snapped it up has been mostly positive. I do have wider reservations about the development of the South Bank / Bankside area since the arrival of Shakespeare’s Globe. A vibrant and historic district for sure but it’s (over) popularity amongst visitors and tourists has slightly dulled it’s lustre in recent years.

A great set of historical images. I believe the structure on the left of one image described as ‘the lower levels of the new chimney’ is actually the pilot flue-gas washing plant installed in 1947 adjacent to Bankside’s oil-fired boilers. This plant was used to evaluate the effectiveness of various flue-gas washing schemes on high sulphur content fuel oil.