London changes at such a rate that it seems every time you walk down a street, there is new building work underway. I was recently walking down Charing Cross Road towards Trafalgar Square and saw scaffolding and sheeting around this building – Seven St Martin’s Place.

Seven St Martin’s Place is between the church of St Martin in the Fields and William IV Street and faces the Edith Cavell Memorial.

There is nothing very special about the building. It is a late 1950s office block with retail space along the ground floor. The company I worked for in the early 1980s had a couple of floors in the building.

What the building does have is a rather good location. Opposite the National Gallery, less than a minute’s walk from Trafalgar Square, at the southern end of Charing Cross Road and close to the Strand – a prime west London location.

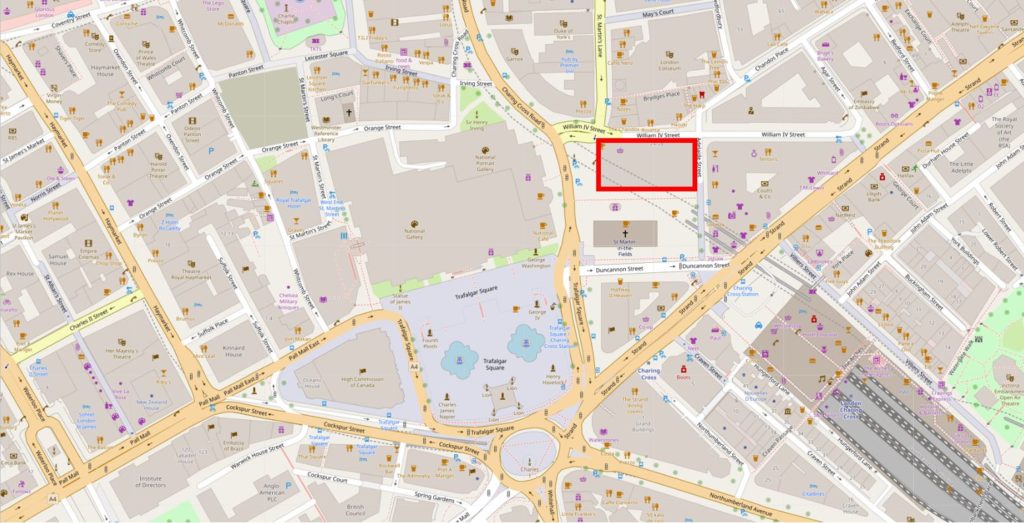

The location of the building is shown by the red rectangle in the following map extract (© OpenStreetMap contributors) .

The reason for the building work at Seven St Martin’s Place is that the building is being converted to a hotel.

The City of Westminster planning decision approves a change of use for the first to fourth floors from offices to hotel accommodation along with extensions at the fifth floor roof level to create a new rooftop restaurant and bar with external terrace,

The existing ground floor retail units will be reconfigured and new retail space created, both at ground and basement levels.

The hotel will consist of 136 bedrooms and be operated by the Butterfly Hotel Group, a Hong Kong based hotel company.

The redevelopment of Seven St Martin’s Place mirrors so much other development across London, where almost any property that becomes available, or can be purchased, is converted to either apartments or hotels. Not in itself a bad thing, providing that residential apartments are affordable, which is rare, or that the diversity of use found across London streets is not restricted.

The planning decision states that whilst “Policy S20 of the City Plan July 2016” resists the loss of offices to residential use, there is no policy that resists the loss of office space to hotel use. Apparently because it is also another use that generates employment, so providing the proposal meets regulations such as noise control, light, appearance, access etc. there is no reason to turn down the application, although an additional Policy S23 does state that existing hotels must be protected and that there are no adverse effects on residential amenity.

I suspect that with the demand for hotel rooms in London, very few applications are turned down.

Building name above the original entrance to the building:

The conversion of Seven St Martin’s Place did get me wondering about how many hotels there are in London and the level of growth as there does seem to be new hotels opening all the time, and at what point is saturation reached?

There are a number of reports available, and a report by London & Partners (the Mayor of London’s official promotional agency) titled “London Hotel Development Monitor – The Investment Hotspot” provides an overview.

The function of the agency is to promote London and the report is very much focused on promoting the city as a tourist destination and the opportunities for hotel development that tourism brings.

The report states that:

- In July 2018 there were 140,000 hotel rooms in London

- An additional 11,600 rooms were expected to be built by 2020

- Room occupancy is significantly high. In 2018, 79.6% of rooms were occupied, slightly behind Dublin (82%), but higher than Dubai (76.4%), Paris (77.1%), Berlin (74.7%) and Rome (70.1%)

An earlier report stated that the City of Westminster had the most hotels, with 433, with Kensington and Chelsea being second at 189. The City of London had 68 hotels.

The report highlights the impact of the 2012 Olympics on the number of hotel rooms opened across London:

- 2012: 8,133 new hotel rooms

- 2013: 1,833 new hotel rooms

- 2014: 5.442 new hotel rooms

- 2015: 3,117 new hotel rooms

The money involved is significant with the report claiming hotel investment in 2015 was £3.9 billion.

This level of growth and investment is expected to continue. A working paper “Projections of demand and supply for visitor accommodation in London to 2050” (Greater London Authority – April 2017) provides a projection of visitor numbers to London over the coming decades, with International visitor growth expected to be:

- 2015 – 18.581 million

- 2020 – 19.992 million

- 2025 – 21.215 million

- 2030 – 22.439 million

- 2036 – 23.907 million

- 2041 – 25.130 million

- 2050 – 27.332 million

Domestic visitors to London, staying overnight will also be growing significantly in the same period;

- 2015 – 12.938 million

- 2020 – 13.964 million

- 2025 – 15.451 million

- 2030 – 16.938 million

- 2036 – 18.598 million

- 2041 – 19.928 million

- 2050 – 22.413 million

Projections are notoriously difficult to get right, but I suspect it is safe to assume that the number of hotels required in London will continue to grow significantly, and there will be many more redevelopments of existing buildings over the coming decades.

The closed Post Office on the ground floor of Seven St Martin’s Place – will this type of business ever return to the retail space of redeveloped buildings, with probably increased rents? The planning decision does confirm that space will be available for the Post Office should the company choose to return.

The growth in hotels across London has been considerable, but to understand the impact on local communities, pricing pressure on the cost of housing, apartments and flats, costs for renting, we must also look at the growth of Airbnb in London, which has been dramatic over the last few years.

The Inside Airbnb site has some fascinating detail on the number and type of accommodation listed, cost, occupancy etc. The overview for London at the time of writing this post shows that for London there are:

- A total of 77, 096 listings, of which;

- 42,758 are entire homes or apartments

- 33,594 are private rooms

- 744 are shared rooms

The supporting data is downloadable. I was creating a graphic showing the number of Airbnb’s for each London borough, but ran out of time (I will add when complete), but for now, along with the new hotel being built, there are 9,411 Airbnb listings in Westminster.

The relative ease and low cost of global travel is driving the rise in tourism, and therefore the demand for accommodation in cities across the world. Other cities such as Venice and Barcelona are taking steps to control tourism, and the growth in Airbnb. These cities also have to manage the rise in tourists arriving by cruise ship – an issue which currently has minimal impact on London, apart from the occasional cruise ship moored by HMS Belfast or at Greenwich. Whilst these methods of travel do not require accommodation in the city, they do drive a high number of visitors who spend little in the host city.

Amsterdam is another city trying to manage ever increasing visitor numbers with a number of steps being taken including the Netherlands Tourist Board no longer actively promoting the country as a tourist destination.

The demand for land and buildings for hotel development is one of the many drivers behind the price of property across London.

In 2010, Seven St Martin’s Place was sold for £41 million and four years later in 2014 it was sold again, with the prospect of change of use to a hotel, for £65 million – a profit of £24 million in four years.

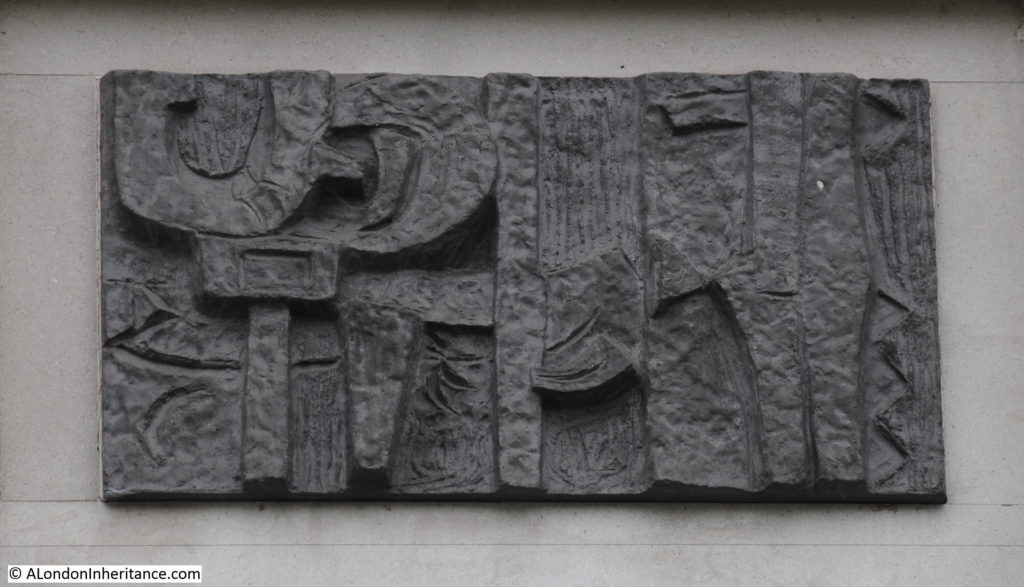

The facade of the building is relatively bland, however there is some interesting decoration on the side of the building facing the Edith Cavell monument. There are two vertical sets of, I am not sure what – artwork, carvings – one panel between each window, creating vertical columns of panels spaced between windows. See the photo at the top of the post for the location of these panels.

Close-up photos of these panels reveal some intriguing designs:

I have no idea as to the origin of these panels, or what they are intended to represent.

The building is not listed, and strangely the planning decision document which details the conditions of planning approval does not make any mention of these panels.

The drawings in the planning document appear to include these panels, so hopefully they will remain.

I have really tried to make out what these panels mean, but cannot find any reference, or looking at them, see any recognisable form or pattern.

I did wonder if put together they would make a map. I have written about the building at 111 Strand, where a map of the area has been carved into the Portland Stone across the 1st to 5th floor of the building.

To see if they made a map, or if there was any other meaning when the panels are combined, I put them together in the same order as they appear on the building:

It does look as if the panels are meant to be combined. There are features that run from one panel to the adjacent. There looks to be a boarder around combined panels. On the far right of the panels, there are vertical wavy lines running down all four panels – could this be the River Thames?

Despite looking at these panels for ages, rotating the photos, trying different combinations, I cannot see any meaning – perhaps there is none. If anyone knows what they mean and who created them, I would be really interested to know.

Although the focus of this week’s post was on the building, and what another hotel conversion means for London, I wanted to have a quick look at the history of the site.

The area demands a full post, so this is a brief look. The 1895 Ordnance Survey Map shows the area as it was around 125 years ago:

Credit: ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’

The street plan is much the same as today, but the block of land that is now occupied by Seven St Martin’s Place was St Martin’s Mews. The Vicarage remains to this day

What is interesting is that the location now occupied by the monument to Edith Cavell, also had a statue in 1895, however it must have been different as the Edith Cavell monument was unveiled in 1920.

On July 18th 1902 a rather impressive statue to General Gordon, mounted on a camel was unveiled in the same position:

But this was seven years after the Ordnance Survey map – I could not find any reference to an earlier statue, but my research time was limited.

The London Metropolitan Archives Collage collection, as usual provided some views of the site prior to the construction of the building we see today.

This is the view of the building that occupied the site, note the entrance to the Mews. The photo is dated 1930 and I suspect are the same buildings that are shown on the 1895 Ordnance Survey map.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_523_A7058

In the above photo, the darker section on the right of the block is the vicarage. This part of the block remains to this day and it is the lighter section on the left that was demolished to be replaced by Seven St Martin’s Place.

The following photo is a 1958 view of the building. As the 1895 map indicates, it was a collection of different buildings with a central mews.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_523_58_2190

As the above photo is dated 1958, it was either demolished soon after, or the references to the current building on the site being a late 1950s office block are wrong, and it is perhaps early 1960s.

The view of the building from William IV Street today, shrouded in sheeting as part of the building work.

Changes to London are gradual, and normally it is only the historically or culturally significant buildings that get publicity when their use is changed, or they are threatened, but there are also so many changes involving rather ordinary buildings from the last half of the 20th century.

Hotels and expensive residential buildings appear to be the main drivers of development, however there still appears to be an expectation for plenty of office space. The 2017 London Office Policy Review for the Greater London Authority projects that office employment across the greater London area will rise from 1.982 million in 2016 to 2.861 million in 2050, so office space will continue to be required in larger volumes to accommodate this workforce.

So with the 2050 projections for both office space and tourism numbers – London is set for a considerable amount of development over the coming decades, and we will continue to see change whilst walking the streets of London, although I am not sure how much trust I would put in future projections.

The 1958 building was rather attractive…

The challenge of the panels! I’m reminded of a puzzle in the film “Contact” based on a book by Carl Sagan. Definitely worth a watch if you’ve not seen it (stars Jodie Foster) – and you’ll see what I mean about the puzzle. Although I don’t think it will help us here.

Thank you for another informative post. re. the sculptural panels: I wonder if the artist may not have been William (Bill) Mitchell, who enjoyed some popularity in the early 1960s. He seemed to capture the zeitgeist but his work is seldom celebrated or reflected on, possibly because the 60s international style plunged into being passe very quickly. He may still be alive, born in 1925. He worked in mutlimedia and was very fond of casting techniques, and produced textured and scculptured pieces often in panel form for ease of transport and installation. Works can still be seen on the exterior of the UMIST building, Manchester, and I suspect the textured concrete panels lining parts of the adjacent Mancunian Way were by him. There are still murals of his at the CIS building reception and Piccadilly Hotel reception, both Manchester. I only know these as I am Manchester-based but he also worked elsewhere.

I think Maggy could be right – take a look at this https://wharferj.wordpress.com/2011/09/02/william-mitchell-an-unacknowledged-genius/

Lots of shapes seem similar – as I live near Ilkley I am going to pay a visit to the magnificent frontage in Ben Rhydding.

Regarding the images on the office building – I wonder if they could be something to do with reflecting the previous usage? There does seem to be an animal at at trough and some kind of reference to work and vehicles.

I sincerely hope these panels are preserved and I will keep an eye open for them. Thanks for another wonderful Sunday morning read.

Wat happened to the Gordon statue? Is there perhaps a London graveyard for unwanted monuments like some oher cities have?

With help from the online archive of The Times, I can add some information about the statue of General Gordon on a camel. The statue was in its pictured location for only a few months in 1902. From 1904 to 1958 it stood in Khartoum near the near the place where Gordon was killed. It was then moved to Gordon Boys’ School in Woking. The school is now co-educational and has changed its name to Gordon’s School. The statue is still in the school grounds. The school’s website has a couple of paragraphs about the statue – see https://www.gordons.school/page/?title=History+of+Gordon%27s+School&pid=92.

By the way, the Ordnance Survey map which is said to be 1895 is actually 1951. The 1895 map shows no statue.

Listening to radio 4 at 8-50am this morning the very subject was tourism and the problems of overcrowding in Florence causing residents to leave +the impact of the carbon footprint, sobering times I think.

To me the panels are typical of abstract relief and sculpture of the 50s: Hepworth, Nevelson, Moore, Nicholson and many more. It might be called constructivism or non-objective art. When I was an art student at the time I learned we were not to ask what these meant or represented! This relief might be an exception but the instant I saw the first panel I recognised the general style.

I can’t remember how I got to your blog, probably trying to find images of the places I lived in the 80s & 90s, but I was in love with your way of sharing history and have delighted myself since…. I went to the map and I can’t find a location/blog post (there is no marker, not sure if you have a post or not) of the Old Vicarage and College for the Students of the St Mary Magdalene Church in Longford St… First time I came to England, the Vicarage was squatted and I ended up living there for a while, the people were evicted but then it was squatted (by mainly same people) again and I came to live there another time, then we travel to get married in South America and it was squatted once again, so once more we lived there….but we soon had grown up and rented a place in South Camden….. then the Vicarage was bought by some Housing Association as it is a Listed Building, they kept at least the exterior as it was, but they turned them into flats… I have some old photos, I think I even got one that does not include any of us, though I doubt any of us would have problems with publication. Your blog is an amazing source of happiness for us here, I am able to share London history with my daughter, would love to see a post about the Vicarage story 🙂 Also, not sure if you have a post about the old Middlesex Hospital in Mortimer St? they had another building in the back of Goodge St, the hospital was sold (great mistake, in my opinion, showing greed of councils) but the Chapel was kept inside the new building the have now … I didn’t find much on the Middlesex in general, I have long and interesting story with the hospital, would love to know a bit more, if you did a post, could you please direct me to it? thanks in advance and thanks for the amazing blog, each post is a jewel!!!!!

Gordon – after a bit of googling it seems the Gordon statue is now in Woking, where it arrived via a detour to Sudan. There’s an interesting potted history here: https://lightwater.wordpress.com/2010/08/16/the-story-of-general-gordons-statue-at-gordons-school/

What intrigues me about the old building is how it was almost symmetrical but not quite, with the vicarage one story taller. I’m wondering if the whole block was built at the same time or whether at one point the vicarage or St Martin’s Mews were added but with the idea that they should match. It’s perhaps surprising that the vicarage lasted when the rest didn’t

A very interesting post, as always. Fascinating what you have done to try to decipher the code in the panels fixed to the block. They do seem to be trying to tell us something. I’ll get my nephews on to it!

I know the area well, having married at the Quaker Meeting House just up the road in St Martin’s Lane…which may be worth a future blog post in its own right. And a friend of mine grew up in the vicarage you refer to, right next the St Martin’s Church.

Your readers may like to be aware that each Wednesday evening, beneath the statue of Edith Cavell, a group of women dressed all in black gather in silent vigil from 6pm to 7pm. They have done so for many years now, in rain, shine, winter, summer, bearing witness to injustices throughout the world, particularly those relating to war, militarism, and other forms of violence. Here’s a link to their work: http://womeninblack.org/vigils-arround-the-world/europa/united-kingdom/london/

A wonderful piece! Not having visited London recently it would be sad to see that the Post Office has left this busy corner. It used to be open 24 hours in the 60s and 70s, a grand place for a lad to purchase new stamps on his way to school. Although when I last visited I was surprised at the scarcity of customers.

The sculptures have been a minor curiosity over the years.

Interesting statistics you provide although I have had a great mistrust of projected and actual numbers since the fifth grade. The caveat I tend to use is check the source!

Thanks again for your writings.

I didn’t know the Post Office had closed there. I remember when it was open 24hours, 7 days a week, although only a small part of it was open after hours. The majority of the counter was closed off, with just the Poste Restante bit open. The basement area, with the public telephones was also closed at night, to stop Trafalgar Square’s resident homeless from setting up for the night. Those people included an old, married couple, affectionately called Mr & Mrs, by my dad who was a manager there for several years.

My dad had many tales to tell about his time there, and was often called to Bow Street magistrates court, to appear as a witness to various crimes that took place in or around, the PO. Pick pocketing was rife, and my dad often gave chase, to apprehend a criminal!

I often visited him at work, and the rest of the staff knew me, which came in handy when needing the loo during the New Year’s Eve celebrations! This was when you could still go in the fountains.

Even after my dad retired, I still visited a lot, as I’d married one of the counter staff! It really became like a second home to me, and I have lots of happy memories of Trafalgar Square PO, and am a little sad that that’s now gone the same way as a lot of the London I remember.

The office space projections surprise me. With more and more workers now working from home, I would have thought it would decrease the need for offices.

The picture of the statue of General Gordon aloft shows his camel to have a horse’s tail as is the case for the similar statue at the Royal Engineers’ HQ, Brompton Barracks near Chatham, where it was unveiled by HRH the Prince of Wales in 1890. One explanation offered for the anomaly is that the sculptor – Edward Onslow Ford – lacked photographs of that end of the animal but another is that the more luxurious substitute avoided offending Victorian modesty.

The two statues have much more in common however since that in St Martin’s Place was a copy of the first while its siting there was intended to be only temporary. Later in 1902, it was sent, eventfully, by sea to Sudan was where it re-erected in Khartoum.

After Sudan’s independence in 1956, both Gordon’s statue and that of General Kitchener came back from Khartoum to the UK. The latter went to Chatham and the former to the eponymous Gordon’s School near Woking where, albeit now needing restoration, it has surveyed the games field since 1960.

Much more of the story can be found on the Kent History Forum and Lightwater sites:-

http://www.kenthistoryforum.co.uk/index.php?topic=15509.0

https://lightwater.wordpress.com/2010/08/16/the-story-of-general-gordons-statue-at-gordons-school/#comments

Finally, noting that these welcome Sunday windows sometimes look out beyond London, may I recommend a visit to the Royal Engineers’ HQ and its Museum? The architecture alone is more than worth the detour while there is also that camel…

Nearly three years ago on an early October Friday afternoon, I wandered down Lower Regent Street to the Mall and thence through Trafalgar Square to this location. However, I alighted here to see the stucco terrace on the opposite (south) side of the building you’ve described. It’s the side facing the north side of St. Martin-in-the-Fields. St. Martin-in-the-Fields Church path connects Charing Cross Road to Adelaide Street here.

Ian Nairn describes the facade on p. 71 of “Nairn’s London.” It’s the old St. Martin’s National School and it’s a lovely building, listed no doubt. It was built ~1830 to a design that evokes John Nash. I lingered there, admiring the noble cream-coloured facade, for at least 20 minutes or so. In 1966, Nairn despaired of it’s future (and noted that the original cream colouring of the facade had been changed to a hideous lime green.) Thank goodness it was saved, and the cream colour restored. I have some photos of it I took that afternoon and will be pleased to send them to you if you like, though I’m sure you can find better specimens on the Web.

I was so taken with this facade that it didn’t even occur to me to examine the building attached to it, which you’ve documented here. Those cryptic panels you describe remind me of Henry Moore’s four sculptures in the “Time-Life Screen” suspended above what was the old Time-Life Building in New Bond Street. When I’m in town and walking through Mayfair, I enjoy strolling past and admiring them, and wonder how many passersby actually realize they’re there, suspended 10 metres above the street.

Very many thanks – your research on hotel development is very impressive and deserves wider publication.

Best

David B

Gray’s Inn

The post office mentioned used to be open 24 hours a day. Imagine that!

You know, one of the things that puzzled me when i first got to England, was (and still is) the lack of 24 hours shops, but mainly pharmacies…. in Brazil & Argentina & in Spain (to mention places I lived in and now the issue) there is at least 1 24hours pharmacy per neighborhood… we live in Hampstead, but lived in a few other places in London, when my daughter was born, we lived in between Euston & Kings Cross/St Pancras…. you would have thought there was at least 1 available pharmacy at night….. with Post Offices, it pains me to see so many amazing, big and convenient branches disappear…. so many employees loosing their jobs, some of these people I had known for more than 20 years….. as much as I love the technology access these days, sometimes I wish we could keep old stuff, especially with architecture… oh well….

Yes, I mentioned that in my comment, my dad used to work there at that time.

We lived and worked in SW1 and SW7, 1980-1992. Whenever visiting St Paul’s church, nearby, we would call in at the Grenadier. My missus gleefully justified it, saying “Thirst after righteousness.” There were great characters to be found at the Grenadier back then.

Just in case someone comes to this entry without seeing the update in the post for 4 August, it seems the panels were made by Hubert Dalwood, from aluminium, for the Ionian Bank in the 1960s. (Some of the planning documents submitted to Westminster Council refer to bronze artwork panels, and the diagrams suggest they will be retained.)

The panels were made by my late father Hubert Dalwood and I am delighted that David has chosen this building to write about and following his intervention and great photos of the reliefs I’m now going to contact the building owners and hopefully get my dad’s sculpture some recognition when the hotel opens.

My dad was a very well respected sculptor in the Modern British movement. His work was commissioned all around the country – public sculpture commissions allowed artists like my father to make large scale work – and a living! His work is in the Tate (currently in the WalkThrough British Art section at Tate Britain) and in many public collections here and internationally.

I was very concerned when I saw the sculptures covered up and so grateful to David for alerting me to what’s happening with the building.

Hopefully I’ll have more to report in due course!

Kathy Dalwood