St Giles has always been a distinctive area. Not in the West End, not part of the expensive streets of Bloomsbury to the north, ignored by those shopping on Oxford Street and bypassed by New Oxford Street and Charing Cross Road. My memories of St Giles from the late 1970s and 1980s are that it always had a slightly edgy atmosphere when visiting in the evening, drinking in the local pubs and the late night bars and music venues.

I had been intending to write a post about St Giles as an area, however working away this last week and the sheer breadth and depth of the history of St Giles swiftly stopped this attempt, so for today’s post I will focus on the church of St Giles in the Fields, a church that has been central to the history of the area for hundreds of years, located to the west of the parish, at the junction of St Giles High Street, Denmark Street and Earnshaw Street.

I visited last June, a gorgeous summer day in London, which seems a long time ago whilst writing this on a grey January day.

The view on leaving Tottenham Court Road Underground Station immediately shows how the area is changing. The space between New Oxford Street, Charing Cross Road and Denmark Street is a major building site. The original site of Foyles disappeared a few years ago.

I walk down Charing Cross Road, along Denmark Street to find St Giles in the Fields:

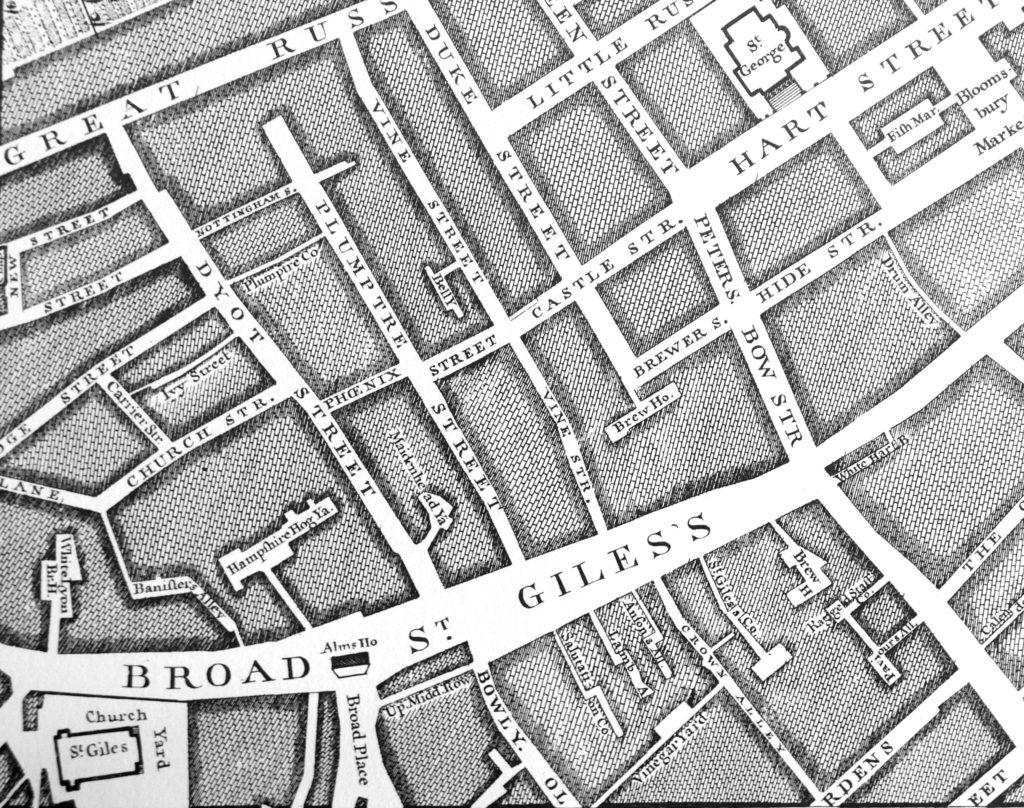

St Giles in the Fields was on the main route that led from Holborn up along what became Oxford Street to Tyburn. The following extract from John Rocque’s 1746 map shows St Giles in the Fields in the lower left corner (unfortunately the corner of the page in my copy of the map, so does not show the area around the church).

The wide street labelled “Broad St Giles’s” connected Holborn on the right with Oxford Street on the left. The significance of the street as a main route was relegated with the construction of New Oxford Street which cut across the streets between St Giles and Great Russell Street to the north. The construction of New Oxford Street was planned as a continuation of Oxford Street and to help with traffic congestion along St Giles. The area north of St Giles consisted of densely packed buildings, courts and alleys and was known as one of London’s notorious Rookeries.

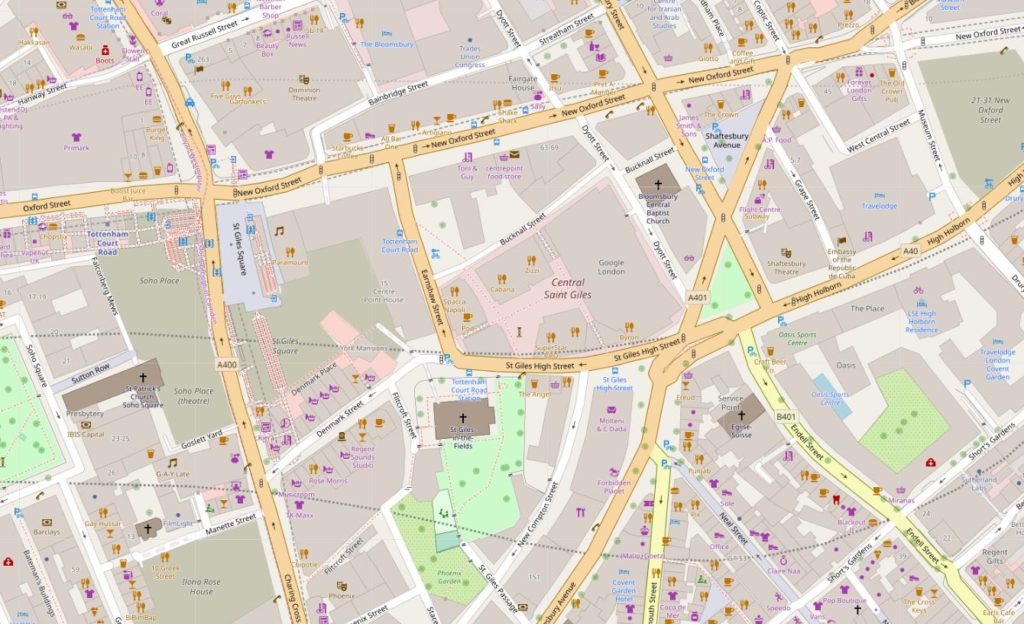

The following map of the area today shows St Giles in the Fields in the lower centre of the map, with Denmark Street continuing to the left towards Charing Cross Road and Earnshaw Street continuing up to New Oxford Street.

It was late morning when I arrived and stalls in the churchyard facing St Giles High Street were setting up ready to provide food and drink to workers and visitors.

The origins of the church date back to the founding of a leper hospital in 1101 by Queen Matilda, when the site of the church was the hospital chapel. With the dissolution in the 16th century, the chapel became the parish church for the small village that had grown up around the original hospital.

St Giles grew into an affluent area and contributions from many of the parish’s wealthy residents allowed the chapel to be replaced by a new church in the 17th century. Edward Walford in Old and New London describes this church as being a “red brick structure, commissioned by Laud, whilst Bishop of London in 1623”.

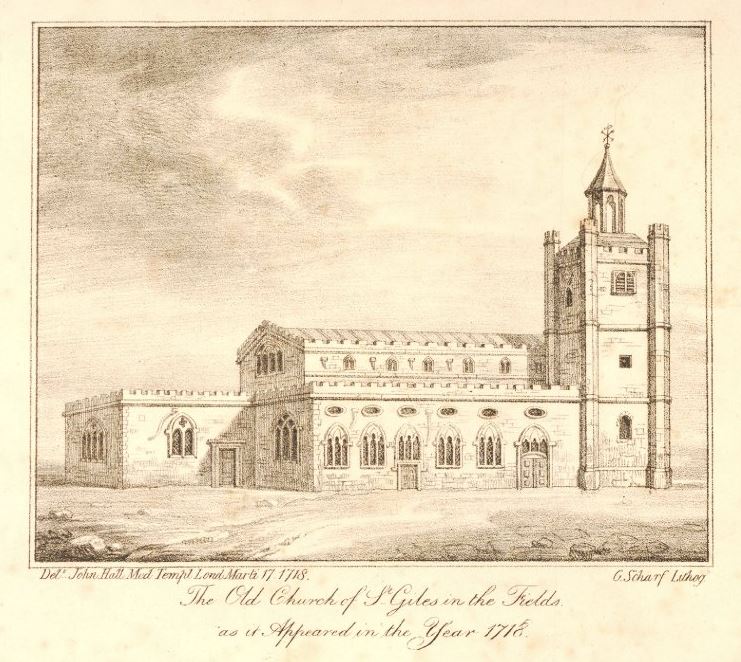

The church of St Giles in the Fields as it appeared in 1718:

This 17th century church was in a very poor state 100 years later, and was demolished to make way for the present church which was built between 1730 and 1734. Edward Walford describes the new church as “a large and stately edifice, built entirety of Portland stone, and is vaulted beneath. The steeple, which rises to a height of about 160 feet, consists of a rustic pedestal, supporting a range of Doric pilasters; whilst above the clock is an octangular tower, with three-quarter Ionic columns, supporting a balustrade with vases, on which stands the spire., which is also octangular and belted. The interior of the church is bold and effective, the roof is supported by rows of Ionic pillars of Portland stone, and the semicircular-headed windows are mostly filled with coloured glass”.

St Giles in the Fields faces to the west and the main entrance to the church is off Flitcroft Street, a narrow street that leads down from Denmark Street.

The following photo is from the entrance to the church looking down Flitcroft Street, a view that still retains the mix of architectural styles and narrow streets that once typified the majority of streets in St Giles.

The brick building between Flitcroft Street and the corner of the churchyard has an interesting history. The tall green doors on the side of the building facing the street may provide a clue, as does the name of the building on the brick apex:

As the wording states, the building was Elms Lesters Painting Rooms & Stores and was used for painting the scenic backdrops used in West End theatres, hence the tall green doors to allow these backdrops to be removed from the building for transport to the theatre.

The main entrance to the church and the associated gateway is from Flitcroft Street which, given the narrowness of the street and St Giles High Street running along the northern boundary of the church, could be considered a strange location.

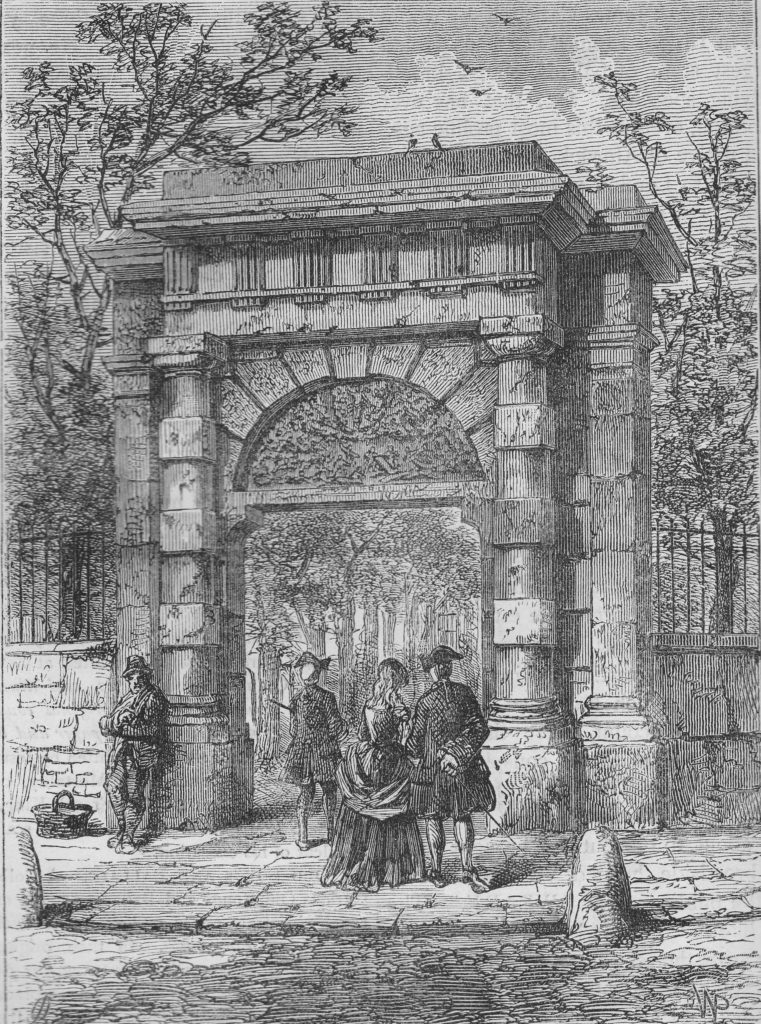

Edward Walford again helps with understanding why the gateway is here “The gate at the entrance of the churchyard which dates from the days of Charles II, is much admired. It is adorned with a bas-relief of the Day of Judgement. It formerly stood on the north side of the churchyard, but in 1865, being unsafe, it was taken down and carefully re-erected opposite the western entrance, where it will command a prominent position towards the new street that is destined sooner or later to be opened from Tottenham Court Road to St Martin’s Lane”.

The bas-relief can still be seen on the arch above the entrance on the side of the gate facing the street. The reference to the new street was to one of the many plans in the 19th century for new streets to be constructed across London to create major through routes, rather than the mix of large streets separated by large blocks of much smaller streets and alleys. The new street referenced by Walford was not built, otherwise Flitcroft Street would look very different today.

Old and New London included a print of the gate in its original position:

Edward Walford’s 19th century description of the church is still relevant today:

There are many monuments within the church, but one of the most interesting is up against the side of the church, with a detailed and well preserved figure of a recumbent woman with an inscription on the stone at the rear of the figure.

The monument is in memory of Lady Frances Kniveton. She was one of the five daughters of Sir Robert Dudley and his wife Lady Alice. Sir Robert Dudley is an interesting character, however his later treatment of Lady Alice demonstrates that the title of “Right Honourable” is not always appropriate. The illegitimate son of Sir Robert Dudley, the 1st Earl of Leicester, he was an explorer, in the days when the majority of exploration seemed to involve capturing Spanish ships.

He tried to prove that he was the legitimate son of the 1st Earl of Leicester, however the majority of evidence that he produced was not convincing and a judgement handed down in 1605 refused to accept that he was the legitimate son.

Soon after he left the country, heading to Italy with his first cousin once removed, Elizabeth Southwell. They settled in Florence, converted to Catholicism, married and Dudley went on to have 13 children with Elizabeth, in addition to the 5 he left in England with Alice.

Lady Alice was made a Duchess in her own right by Charles 1st. She lived in St Giles and contributed significantly to the church.

The text at the bottom of the inscription explains why the monument was saved from the original church and installed in the 18th century church. Old and New London explains: “This monument was preserved when the church was rebuilt, as a piece of parochial gratitude to one whose benefactions to the parish in which she resided had been both frequent and liberal. Among other matters, she had contributed very largely to the interior decoration of the church, but had the mortification of seeing her gifts condemned as Popish, cast out of the sacred ediface, and sold by order of the hypocritical Puritans.”

There are two pulpits in the church, the traditional church pulpit:

Along with a pulpit that came from the West Street Chapel, John Wesley’s first Methodist chapel in London’s West End (West Street is between Shaftesbury Avenue and Upper St. Martin’ Lane).

The inscription on the front of the pulpit informs that John and Charles Wesley preached regularly from the pulpit between 1743 and 1791.

There is a rather magnificent model of the church, within the church:

The model was made by Henry Flitcroft, the architect of the church, to demonstrate to parishioners and those funding the construction of the new church, what his design would like like when completed.

The architect’s name also explains the origin of the name of the small street to the west of the church where the main entrance is found – Flitcroft Street.

View looking towards the entrance of the church:

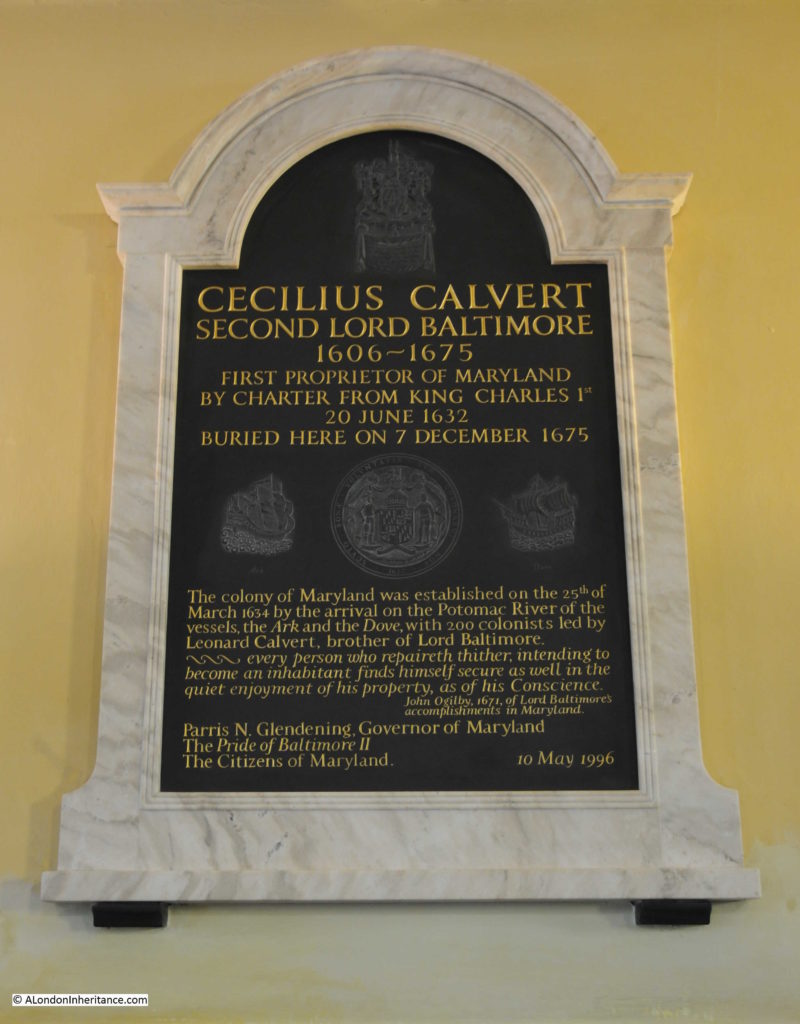

There are numerous monuments around the church. Members of the East India Company, solicitors from Lincolns Inn Fields, and one of the latest, dating from 1996 is to Cecilius Calvert, the first proprietor of Maryland:

Cecil Calvert was the Second Lord Baltimore (hence the name of the city in Maryland). He had been to the Americas once in 1628 with his father to the newly established colony in Newfoundland, however the colony failed and Cecil returned to England with his father.

The charter for Maryland was granted by Charles 1st to Cecil, however he would never visit his colony. It was overseen by his brother Leonard and later by his son Charles.

The above monument dates from 1996, the following is from 1677:

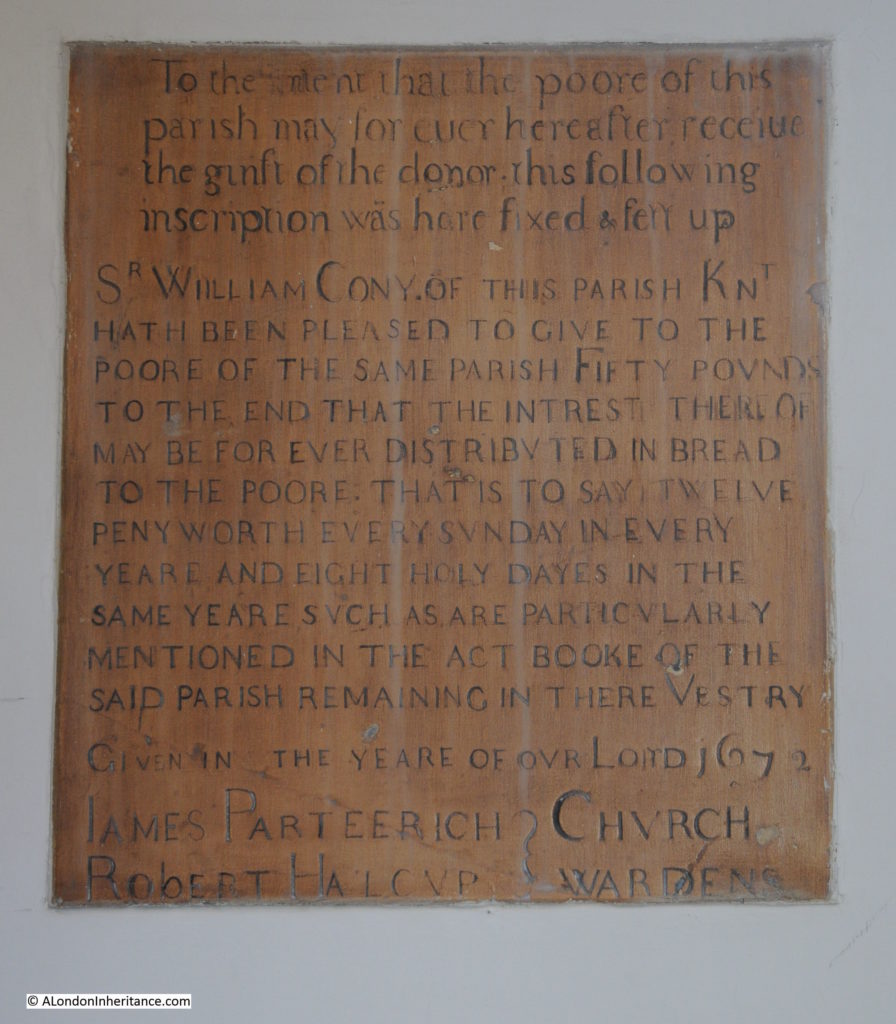

This records the donation of £50 to the church wardens of St Giles in the Fields by Robert Bertie with the intention that the interest from the £50 would be used to buy bread for the poor of the parish “for ever” commencing on the 1st January 1677.

Robert Bertie was the son of another Robert Bertie, the Earl of Lindsey who was Lord Great Chamberlain at the time of the English Civil War. Robert Bertie was a Royalist supporter and General in Chief of the Royalist forces at the Battle of Edgehill. He disagreed on the military tactics for the battle with the much younger and inexperienced Prince Rupert who led the cavalry forces. Charles 1st eventually supported Prince Rupert’s strategy, Robert Bertie resigned his position and went to fight with his own supporters. he was badly wounded and died soon after the battle.

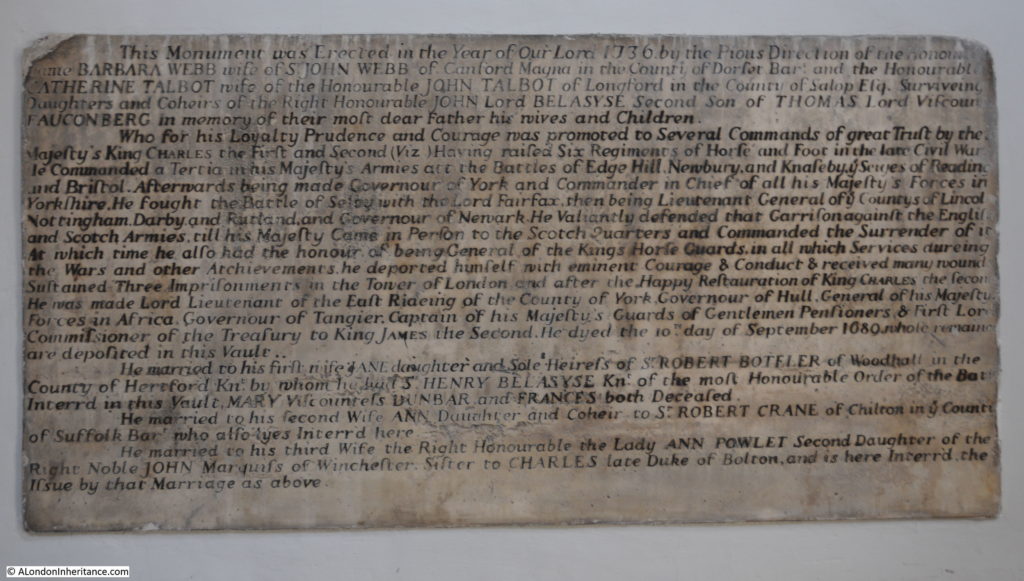

The Civil War and Battle of Edgehill features in another monument. the following erected in 1736 by the family of John Belasyse, 1st Baron Belasyse.

John Belasyse also fought at the Battle of Edgehill, which he survived, along with many of the following battles and sieges of the Civil War. He went underground during the “Commonwealth of England” and following the restoration, Charles II gave Belasyse many senior appointments and positions of power.

An unusual plaque for the interior of a church is the blue plaque for George Odger:

George Odger lived nearby at 18 St Giles High Street. He was a 19th century trade union leader, active in the London Trades Council and later the Trades Union Congress. The blue plaque was installed on the house in the 1950s and moved to the church when the house was demolished in the 1970s.

18th century lead cistern:

Another donation of £50 for the purchase of bread for the poor:

Heading back outside the church, turning left from the main entrance takes you round to the large graveyard to the south of St Giles in the Fields.

View over the graveyard, which as with the majority of city churches, has been cleared of gravestones.

The rear of St Giles in the Fields somewhat obscured by trees.

St Giles in the Fields now looks on an area that will change beyond recognition over the coming years. Change has already started and the arrival of Crossrail at Tottenham Court Road will accelerate that change.

These are some of the new developments around St Giles:

I suspect this relic, just outside the church, from not that many years ago, will not last long in the new St Giles:

Again, a very brief look at the history of one building, only touching on a few points from a very long history.

St Giles has a fascinating history which I will explore further in the future, but walking around the streets today feels very different to when I started going out in London.

Delightful. Thank you. I enjoy your articles very much.

Love this blog.

Particularly liked the explanation of those tall green doors – would never have guessed!

Very interesting, Admin. By the way,did you quench your thirst next door at the Angel pub (another one.)

It has become one of our favourites, when we are in this area.

Many yers ago I worked very near this church and spent many lunch hours sitting in the church yard with my sandwiches. It was a very peaceful area in contrast to the hubbub of only a few yards away.

It is indeed sad to see the church today surrounded by the monstosities that pass for architecture these days (in my opinion).

Thanks for reviving my memories; I look forward to the blog on the surrounding area.

Unless I’m mistaken, that telephone box is a K2, designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott in 1924. Quite rare now…the one near me (behind The Ship on Kennington Road) is Grade II listed. I hope the one in St Giles is similarly protected!

Very well written and interesting.

Those multi-coloured office blocks are in fact Google’s HQ

Another interesting read on a Sunday morning .

Thanks for this, really interesting. I drove through the area recently, and was shocked by the changes being made. It’s hard to imagine the new buildings creating an atmosphere, such as that which has now been lost. Back in the 1980s there was a very good Greek restaurant close by, and a night or two spent in the Angel pub. Happy days…

Not an area I know, but the history you show us recorded inside the church is so true of such parish churches, not only in London. I only wish the epitaphs were signed by their writers, too.

Many thanks.

Thanks, very interesting.

Just around the corner is the Swiss Church in London, in Endle Street.

The Swiss have been around Leicester Square area for hundreds of years

and you can find alot of history on their web site https://swisschurchlondon.org.uk/church-community/history/

Thank you for this excellent piece on St Giles Church. I live directly overlooking the church which, along with the surrounding area never cease to fascinate me. I believe the church and its gardens deserve more appreciation that they generally receive. You rightly comment on the unprecedented level of development surrounding the church, which is heading soon towards its tricentennial.