I have just added three new walk dates, links for details and booking are here:

The South Bank – Marsh, Industry, Culture and the Festival of Britain on Saturday 8th November – 1 ticket remaining

The Lost Streets of the Barbican on Sunday 9th of November – Sold Out

Possibly two more dates coming, but that will be it until late spring / early summer next year.

There are loads of small things across London that tell a larger story of the history of an area, a building, and of how the city continues to change.

For today’s post, I am going to visit three of these, that each show a different aspect of the city. History, change, and how sometimes one can find a survivor from a very different past.

At the end of the post, as it is the first Sunday of the month, I have another section on the resources available for discovering the history of London, and for this month I am looking at Charles Booth’s Inquiry into Life and Labour in London, but first a trip out to Battersea:

The Remains of a Battersea Gas Holder

I was in Battersea recently, and within all the recent new developments, there is a short length of ironwork, that looks as if it was once part of a gasholder:

This can be found where Palmer Road meets Prince of Wales Drive, a couple of minutes west of the Battersea Dogs and Cats Home.

Although this area has been considerably redeveloped, with many new apartment blocks occupying the space between Prince of Wales Drive, and the railway lines that run either side, this area was once heavily industrialised and was home to a collection of gasholders that provided storage space for gas being piped to the surrounding population.

On the wall leading off to the right are a number of plaques and artwork, including the following:

The above plaque was once mounted up on the side of one of the gasholders and bears the name of Robert Morton, a gasholder engineer who was responsible for many of the gas holders that once occupied the space. The year 1882 is the year of the gasholder’s completion.

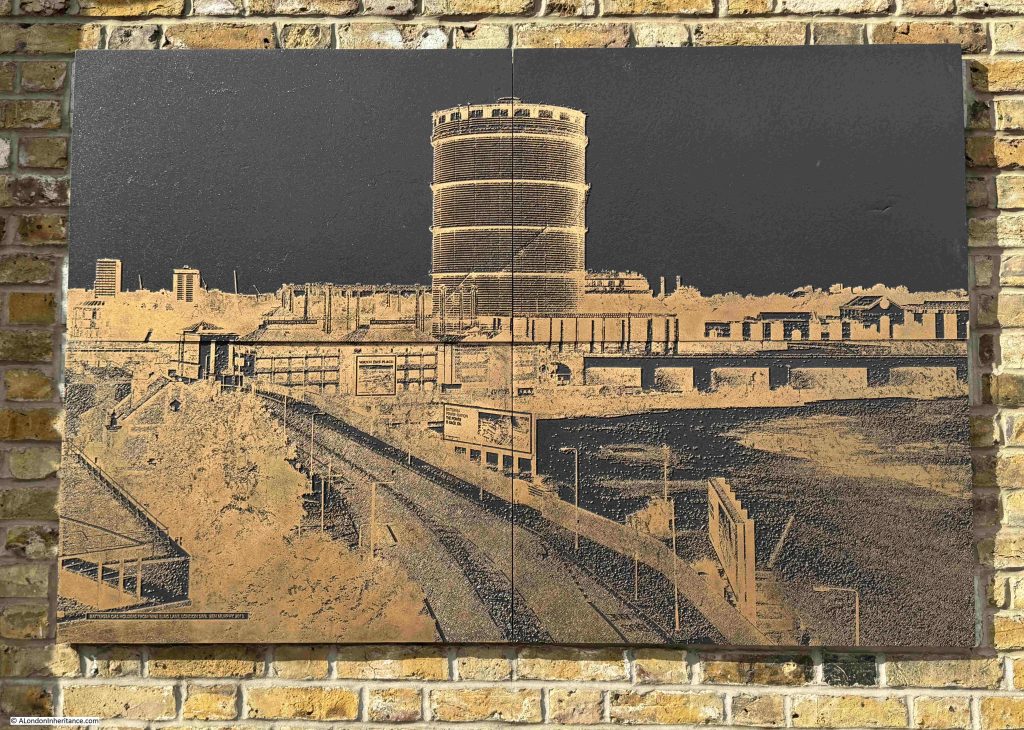

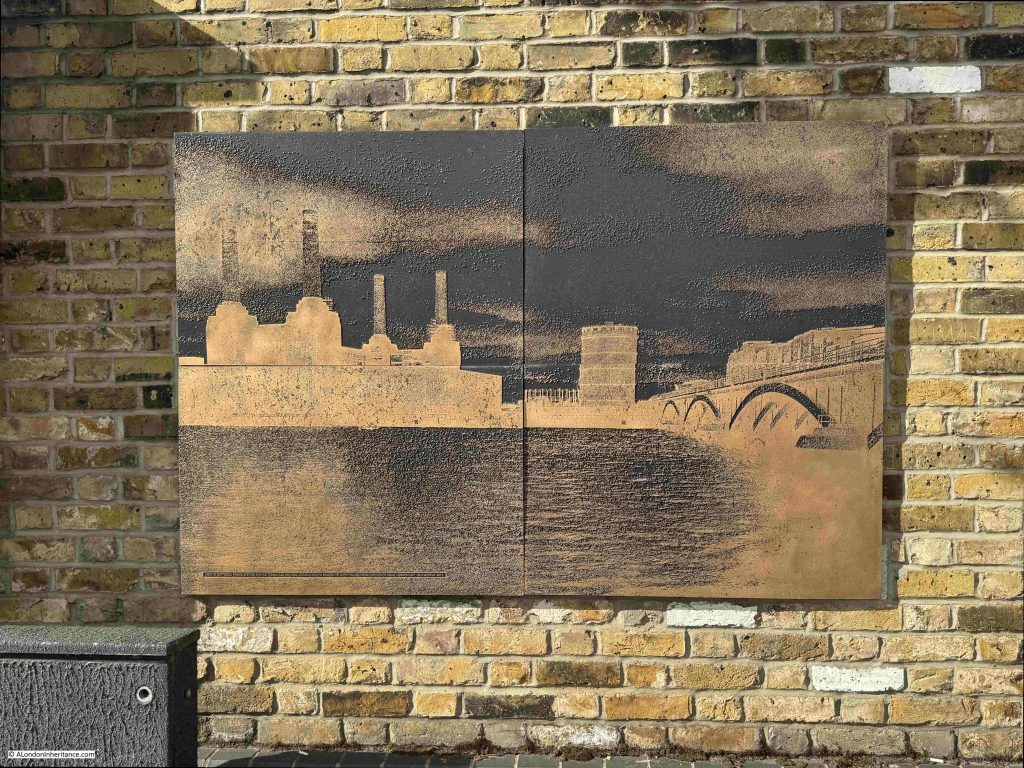

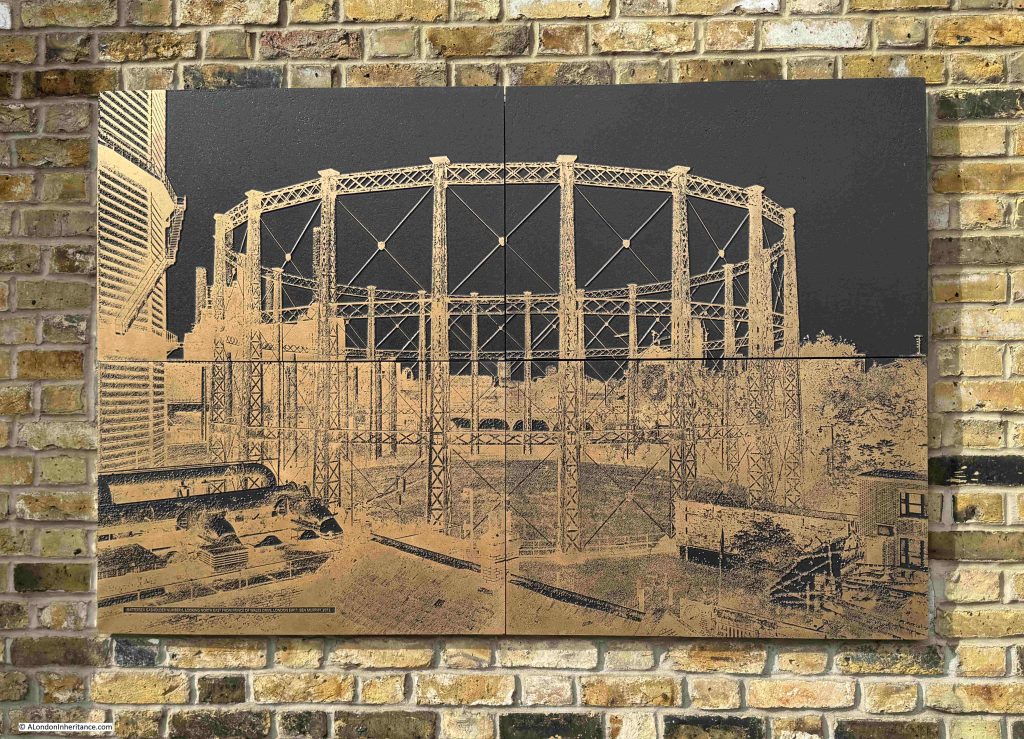

There are also a number of images where a photograph appears to have been etched onto a stone panel.

The photographs are by Ben Murphy who was commissioned by National Grid to photograph UK gasholders, including the demolition of Battersea’s gasholders:

The gasholder in the above image is the “blue” gasholder that was the stand out feature, alongside Battersea power station.

I believe it was the last gasholder to be constructed at Battersea, having been completed in 1932 and was a 295 foot high, water tight holder.

My father took the following photo of Battersea Power Station, with the holder to the rear in the early 1950s:

I took the following photo in 2015, not long before the gasholder was demolished:

One of Ben Murphy’s photos shows a similar image:

Another plaque from the old gasholders, the cross of St. George:

Another of Ben Murphy’s photos:

Another plaque from the gasholders with the cross of St. George, Robert Morton and the slightly earlier date than the previous plaque of 1876:

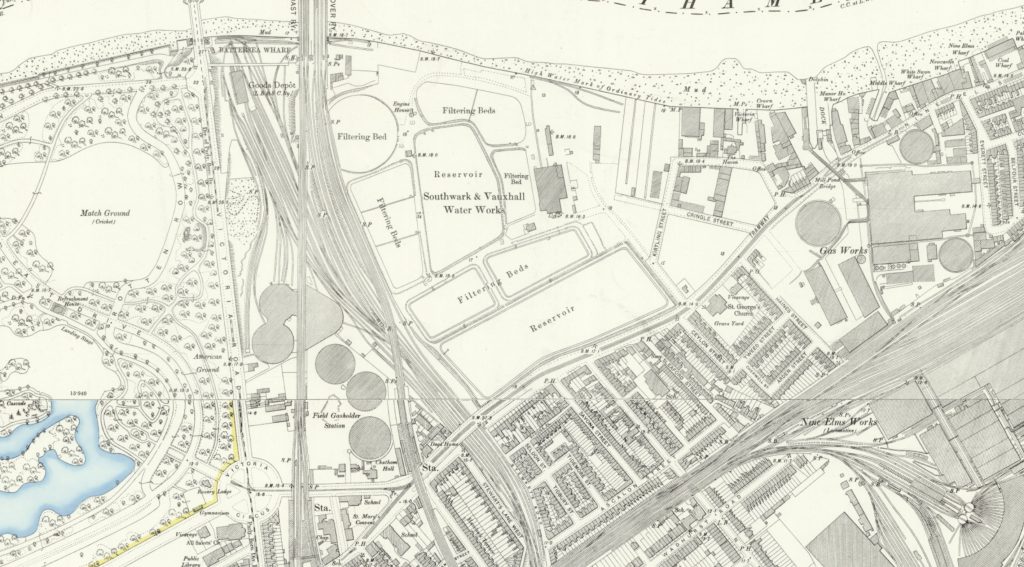

The gasholders were originally part of the London Gas Light Company, and the company built the holders starting in 1871 as an extension to their existing holders and gas production plant at Nine Elms.

They ended up as being part of National Grid’s gas distribution network by the time they were decommissioned and demolished.

In the following map extract from the 1894 revision of the OS map, the gas holders can be seen to the lower left of centre as a collection of circles amongst the railway lines. To the right side of the map, three circles and the works of the London Gas Light Company can be seen at Nine Elms. It was here that gas was made from coal, which had been brought along the Thames and unloaded at the Dolphin which can be seen on the foreshore of the river. In the centre are the reservoirs and filter beds of the Southwark & Vauxhall Water Works. It was on the site of the water works that Battersea Power Station would be built:

(Map ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland)

It was an area that had been supplying either water, gas or electricity to the area for many years.

The Britain from Above archive has the following 1934 photo showing the first half of the power station complete and operational, with the gas holders to lower left:

I cannot tell or find out which of the gasholders the iron structure is from. It is not in its original place, as the current location is too far south, and if a gasholder was on the site, it would have covered Prince of Wales Drive, which is in the same place today as it has always been.

Meanwhile, development of the land around Battersea Power Station continues. The following is the view along Electric Boulevard from Battersea Park Road. The space on the right behind the hoardings will not be empty for long:

National Grid commissioned the following video of the demolition of the gas holders:

There only appears to be a single gas holder in the video that matches the ironwork on display today.

Sad to see these remnants from an earlier industrial past demolished.

Church of Notre Dame de France

The Roman Catholic Church of Notre Dame de France is in Leicester Place, which leads north from the north eastern corner of Leicester Square.

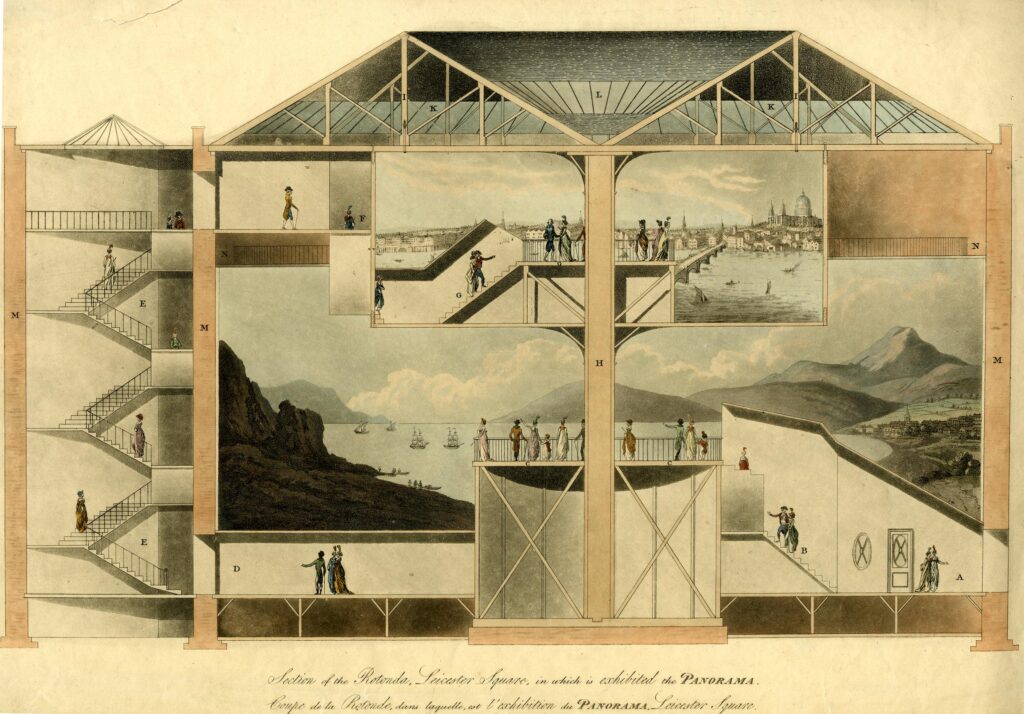

I have long wanted to visit the church as the shape of the interior of the church follows the shape of a building that was on the site and which provided a panorama of views of places and events across the world, to entertain and educate the people of London.

The site started as the home of Leicester House, which had been demolished around 1792.

A large rotunda was built on the site between 1793 and 1794 and which opened as a panorama. This continued to be the building’s use, and by the middle of the 19th century, it was occupied by Burford’s Panorama, and the following from the Illustrated London News on the 7th of June, 1851 gives an idea of the panoramas available:

“BURFORD’S HOLY CITY of JERUSALEM and FALLS of NIAGARA – Now open at BURFORD’S PANORAMA ROYAL. Leicester Square. the above astounding and interesting views, admission 1s to both views, in order to meet the present unprecedented season. The views of the LAKES of KILLARNEY and of LUCERNE are also now open. Admission, 1s to each circle, or 2s 6d to the three circles. Schools half price. Open from 10 till dusk.”

To see how the church and Burford’s panorama are linked, I recently had the opportunity to visit the church when it was open, and no service in progress.

This is the building and entrance to the church in Leicester Place:

The main entrance with a carving of Our Lady of Mercy by Professor Saupique of Paris:

On either side of the entrance, there are carved pillars. These show scenes in the life of the Virgin and are by pupils of Professor Saupique:

Professor Saupique was Georges Saupique, a French sculptor who was born in Paris on the on 17th of May 1889. The second pillar:

The front of the church facing onto Leicester Place dates from a 1955 rebuild of the church.

Through the entrance, and this is the foyer that leads to the interior of the church:

And through the doors in the above photo, we can see the circular layout of the interior of the church:

The interior is also a 1955 rebuild of the original church, but seems to follow the same circular plan as the first French church on the site, a building which made use of the building constructed as a panorama, and used by Burford’s panorama in the mid 19th century.

A cross section of the rotunda, with the internal panorama displays is shown in the following print (© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.):

The following link to Google maps shows an aerial view of the church, where the round body of the church can be seen, on the same footprint as the rotunda:

https://www.google.com/maps/search/leicester+square/@51.5114146,-0.1300492,49m/data=!3m1!1e3

The domed roof to the church:

On the 25th of March 1865, Father Charles Faure purchased the building that housed Burford’s Panorama. and the French architect, Louis Auguste Boileau transformed the building into a new church within an iron structure.

The new church opened in 1868 as Notre Dame de France, a French speaking church in London, to serve the large French population based in and around Soho,

The church suffered bomb damage in the Second World War, it had some temporary repairs, but was rebuilt between 1953 and 1955 to a design by Professor Hector Corfiato, a graduate of the École des Beaux Arts de Paris, and this is the church we see today.

A side view of the interior of the church:

There are a number of works of art within the church. Behind the altar is a large tapestry, designed by the Benedictine monk Dom Robert de Chaumac on the theme of Paradise on Earth:

The Lady Chapel is on the northern edge of the circular church. There are three murals in the Lady Chapel, on the rear wall and the two side walls. These show the Annunciation to the left, on the rear wall is the crucifixion, and to the right is the Assumption.

The murals date from 1959 and are by the French artist Jean Cocteau:

The church itself and the internal and external decoration are fascinating, and it is still a very active church for a French congregation.

What makes it unique though from a historical and architectural perspective, is that it follows the same footprint as a rotunda built at the end of the 18th century, which has resulted in the circular form of the main body of the church we see today.

All Hallows Staining and 50 Fenchurch

I have written before about the church of All Hallows Staining, based on the photo my father took of the church in 1948:

Only the tower remains, and the tower is currently part of the construction site on which 50 Fenchurch Street is being built.

All Hallows Staining was featured across online, printed and broadcast media last week, as the tower is now suspended in the sky, on stilts, as the ground beneath the church has been dug out as part of the large below ground open space which is part of the new building.

The BBC have a video of the tower on their website at the following link:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/videos/cr70e8ez0k8o

It is quite a remarkable site, so last week I visited the site to try and get a photo.

The construction site is large, and is surrounded with a large green painted hoarding which prevents any view of the site. There are a couple of gated entrances, but asking if I could get a photo met with the inevitable reply of not possible.

I did manage to get a couple of photos. The following is looking through the gap between a gate and the hoarding – the large hole in the ground continues under the church tower:

The second photo was taken through the main entrance. I asked if I could just walk over to the concrete edge to take a photo,. but no luck.

In both photos you cannot see below the church tower, which would be the key image of the tower suspended above a large hole in the ground.

The hoarding around the site obscures any view of the construction site. It is a real shame that construction companies hide their work as these are remarkable examples of construction and engineering.

Another site which will soon see a large tower rise over Fenchurch Street in the coming years.

Resources – Charles Booth’s Inquiry into Life and Labour in London

There is often a tendency to look back at the past, and imagine it was a more socially better world, where front doors could be left unlocked, everyone knew their neighbours, there was less “red tape” governing business and trade, not so much violent crime etc, however even a brief reading of newspapers of the 19th century will show the casual attitude to accidental death, the level of crime, and how many in the city were reduced to a state of poverty and destitution, and being a child on the streets, particularly for a girl, could result in a short life of crime, poverty and worse.

The 19th century was a time when London expanded considerably, and became a major, if not the major, trading and industrial city in the world.

Whilst so much Victorian effort and entrepreneurship was applied to trade, industry and the business of making money, there were also many who wanted to understand and improve the life of the poor. Who wanted to understand the social conditions of the city, what could be done to help, what laws needed to be brought in or changed, how initiatives such as a state pension could help etc.

One of these was Charles Booth. Born in Liverpool in 1840, and a successful businessman, his name would forever be associated with the survey of London that he and his wife Mary Macaulay carried out from 1889, to the last volume being published in 1903 of the “Inquiry into Life and Labour in London”.

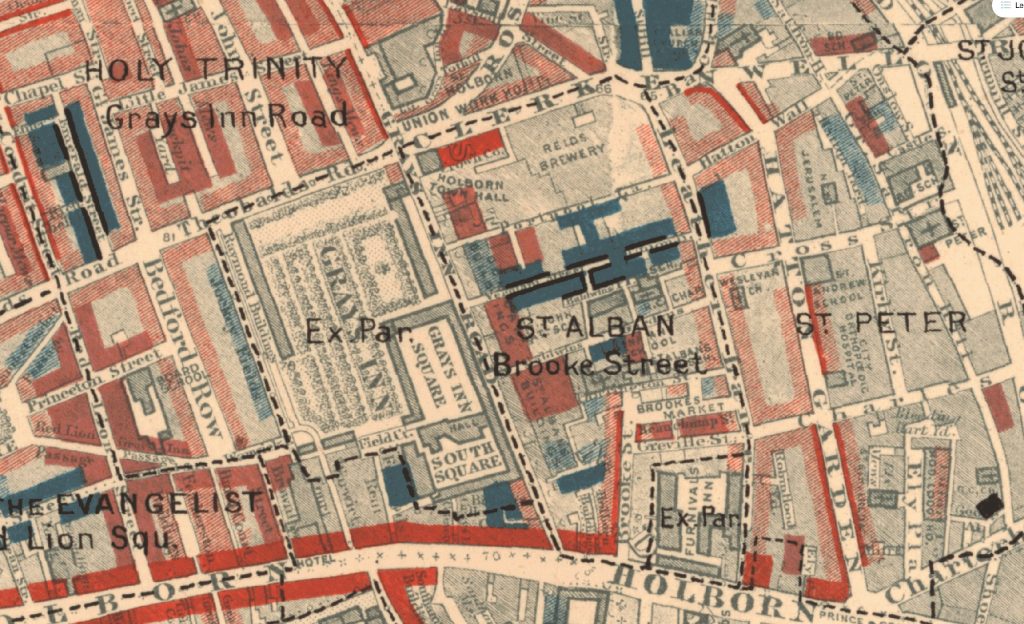

The inquiry focused on three broad themes – poverty, industry and religious influences, and the results of the survey were summarised with a series of colour coded maps, and the publication of the many notebooks that covered the information collected by those engaged in the inquiry.

I will not go into greater detail, as the purpose of this section is to point you to where there are resources to help with researching London, and the London School of Economics and Political Science (the LSE), have done a fantastic job by putting the maps and notebooks online, along with a background to the survey and a biography of Charles Booth.

The home page of the LSE’s website devoted to Charles Booth can be found here: https://booth.lse.ac.uk/

The following is a sample from one of the maps. The streets were colour coded, with darker colours indicating increasing rates of poverty and criminality and colours up through red to pink indicating increasing levels of prosperity:

As usual, the maps and notebooks need to be read with an awareness of the prejudices and opinions of the time, but having said that, they do provide a really good insight into Londoners lives at the end of the 19th century, an insight that was both broad and deep.

The notebooks are also all online, and record the investigators notes and findings. Many of these are hard to read, but they do provide a vivid picture of the city at the time.

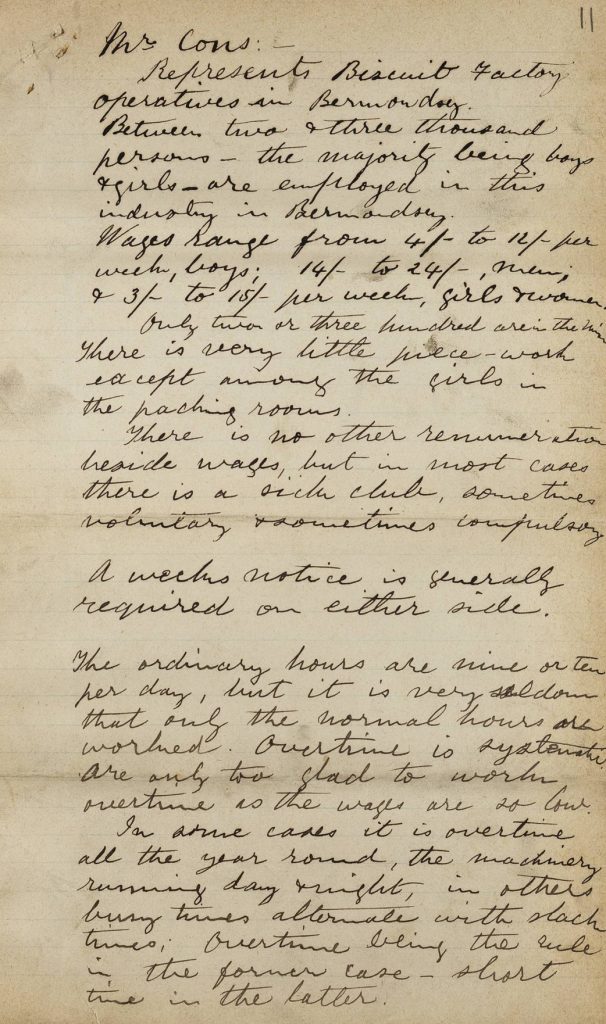

The following is an example (I have provided a transcript below the image):

I cannot decode the name at the top, however they “Represents Biscuit Factory operatives in Bermondsey. Between two and three thousand persons – the majority being boys and girls – are employed in this industry in Bermondsey.

Wages range from 4 shillings to 12 shillings per week, boys; 14 shillings to 24 shillings, men and 3 shilling to 15 shillings per week, girls and women.

Only two of three hundred are in the ….. There is very little piece work except among the girls in the packing rooms.

There is no other renumeration beside wages, but in most cases there is a sick club, sometimes voluntary, sometimes compulsory.

A weeks notice is generally required on either side.

The ordinary hours are nine or ten per day, but it is very seldom that only normal hours are worked. Overtime is ……. are only too glad to work.”

The LSE have done a brilliant job at putting all of the resources online and making Booth’s survey, both the maps and notebooks are fully available – they provide a fascinating and informative insight into London at the end of the 19th century, and again the link is here: https://booth.lse.ac.uk/

Another fascinating post – thanks as ever.

The blue gasholder at Battersea was unusual, if memory serves, for being at a constant height, not rising and falling according to the quantity of gas being held.

In his notes, might Booth have written ‘Only two or three hundred are in the Union’?

That is correct, the type of gas holder here referred to as the “blue gasholder” has an internal piston that moves up and down and nothing of this is visible externally. The post describes it as “water tight”‘ this is not so, it is a waterless gasholder where the gas tight seal is created by grease or tar on the rim if the piston. In the aerial phohotograph that shows the four gas holders (Britain From Above) the 3 gas holders adjacent to the blue gasholder are water seal gas holders where the external structue moves up and down within the ironwork frame depending on the volume of gas within, below ground is a water reservoir which creates the seal.

Yes, I concur that it says two or three hundred are in the union.

Also, further down the page it states that overtime is systematic.

If you expand the page it is easier to read.

I’ve got to tell you how much I love your articles.

Thanks for your latest.

I think the missing bits of the Booth transcription might be:

“Only two of three hundred are in the …..[union]

Overtime is [systematic. Are] only too glad to work.”

Keep up your wonderful work.

All Hallows Staining – Oh No!

I hung up my City briefcase in 2011 and got relocated to deepest Essex. Have not gone to The City since and shocked at the transformation after viewing Streetview. Many a happy lunchtime spent browsing the regular sales in the church hall. So sad the City is losing all of its history among the concrete and glass.

Note, your reports for some time now appear in duplicate, one after another in the email link.

I suspect the name at the top of the report into Bermondsey Biscuit manufacture is ‘Mrs Cons’ and the author is Emma Cons (1838–1912), a noted social reformer. Beatrice Webb also worked for the Charles Booth survey.

George Duckworth, Virginia Woolf’s (notorious) half-brother, was Booth’s unpaid secretary, 1892-1902, & is credited with writing 2000 pages of the Notebooks. I’ve had reason to consult the online notebooks for Hammersmith & Marylebone, the two London neighbourhoods where I once lived, & cannot praise the LSE enough for making these irreplaceable resources so easily accessible.

Could the name at the top of the Booth notebook be ‘Mrs Cons’, i.e. Emma Cons, the social reformer.

The French Church is a wonderfull refuge from the now very overcrowded and clamorous West End. Just to go in there and sit in the peace and quiet for a while is such a restorative. Fantastic post all round. Thank you for all the effort you put into these reports.

My grandparents moved to Staples Rents in Rotherhithe about 1898. Booths 1899 report described Staples Rents as ’18 homes narrow children dirty’. Perhaps those children were my uncles!

The French Church I visited a few times when attending French language classes in the early 1960s and also being a member of the Club Charles Peguy nearby in Leicester Square area.

Also call to mind your references to the Festival of Britain on South Bank: the atmosphere was quite magnificent, full of enthusiasm and optimism for the immediate future. The area between Charing Cross and Waterloo stations ie the walk over Hungerford railway bridge was crowded and miserable and was walked as fast as possible to get away from it, but there still remained that worst piece of ground after the bridge ie between the river bank to Waterloo Station which had to be crossed: it was quite depressing indeed. Remember with fond admiration the trams that still ran along the Embankment…I just managed to visit the exhibits of the Festival in early June, my summer being over being called up for national service in first few days of July…Relatively happy memories with much to learn…

Gasholders! I’d forgotten the blue one existed – your photo reminded me that it was one of those landmarks you never consciously think about, as I went across London back in the day. I used to live in King’s X opposite the listed RoMos (to coin a phrase) that were moved to ‘create’ what I believe is now ‘Gasholder Park’. That’s property developer lingo for monstrosity masked by novelty.

Another fascinating blog.

Back in April (2025) I took my 8 year old granddaughter on a sightseeing trip to London. The view from The Garden at 120 (Fenchurch Street) overlooks All Hallows Staining and the construction site that is 50 Fenchurch Street. I managed a couple of photo’s through the glass balustrade, so not brilliant but it gives an indication of the site size in relation to the tower. (Happy to forward if required). At this stage, April, I believe it was still grounded rather than levitating!

Charles Booth’s Inquiry into Life and Labour in London is not only an excellent resource for social history but also family history.

You can get a good view of All Hollows tower – currently on stilts within the building site – looking down from the roof garden at 120 Fenchurch Street

The gasholders and nearby railway arches could be argued to be where flying first started despite the first flight at Farnborough by an American.

As described in the readable book “The Balloon Factory” by Alexander Frater 2008 Londoners used the gas supply to fill their balloons (not hot air balloons) around 1900 plus. The land to the South was still countryside so ideal for a launch next to the gasometer. A factory opened up in one of the railway arches to aid this new hobby. Soon London was built up and it was no longer suitable and ballooning ceased, however experiments in flight started with people building aircraft in their homes, yes really!