I find it fascinating the random bits of information you discover when researching London’s history. Last year I had taken some photos of the cluster of memorials in the centre of Waterloo Place, just north of Pall Mall. They perhaps give the impression of a cluster erected at the same time, commemorating aspects of the Crimean War, however they are from different centuries, parts were very controversial at the time, and in 1915 newspaper reports of an addition to the cluster reported that it included “The First Public Statue of a Woman in London” – other than those of Royalty, such as Queen Ann or Victoria.

It is an interesting statement from 1915. Firstly that even with the Victorian love of statues, there had not been a statue of a woman (apart from the many statues of Queen Victoria), and secondly, that it was an event that newspapers recorded, perhaps an early indication of changing attitudes, however reports were just a statement of fact and there was no further discussion.

Statues often seem to generate polarising views, the latest example being the sculpture by artist Maggi Hambling for Mary Wollstonecraft at Newington Green which was unveiled last year, and those in Waterloo Place were equally controversial at the time. They also signify events and people who were considered important at the time, and views change over time.

The following photo shows the cluster of statues in Waterloo Place, viewed from across Pall Mall, from the southern section of Waterloo Place.

The cluster is facing to the south east, so the best view is after walking up the steps from The Mall and through the lower part of Waterloo Place. Regent Street St James’s is directly behind the group, leading up from the north western side of Waterloo Place towards Piccadilly.

A closer view of the cluster of statues on their island location:

Although the cluster of statues may give the appearance that there were part of a single installation, there were fifty four years between the central monument (1861) and the two statues at the front of the cluster (1915).

The “First Public Statue of a Woman in London” is one of the statues installed in 1915, and I will come to these later in the post.

The central monument is the Guards’ Memorial and was erected in 1861 as a memorial to the 2,162 soldiers of the Brigade of Guards who had lost their lives in the Crimean War. It was the work of the sculptor John Bell, who was also responsible for the 1856 marble Crimean memorial in Woolwich and the “America” group on the base of the Albert memorial.

The current location of the memorial was the third option, after sites in Hyde Park and St James’s Park had been considered.

At the top of the monument is the figure of Honour, standing with outstretched arms.

Below the figure of Honour are three soldiers dressed in full marching uniform representing the Grenadier, Coldstream and Fusilier Guards.

The figures were cast at the Elkington and Co. foundry in Birmingham and they were made from guns taken from Sebastopol in the Crimea. The old guns were broken up at Woolwich, then sent to Birmingham.

One hundred tons of granite was used for the pedestal and surrounds of the monument. The granite came from the Cheesewring quarries in Cornwall.

The Illustrated London News on the 13th April 1861 was very scathing about the new monument:

“The Guards’ memorial as it now stands before us, must be confessed to be an eyesore, and an obstruction of the public view of one of the most agreeable outlooks which our crowded thoroughfares afforded; and suggests the absolute necessity of some provision being made in this ‘testimonial’ age to prevent our streets and squares being blocked up in all directions with unsightly effigies to departed worth, however honourable the sentiments which may lead to their construction.

As a work of art this memorial is almost beneath criticism. It may be said of it with perfect truth that it is unique; nothing like it has ever been seen – nothing else like it, we trust, ever will be seen. It is neither sculpturesque nor architectural, nor jointly both. A heavy, irregular structure of granite is the principal object, filling up a considerable area in the roadway.

Independently of the hideousness of the granite pile, the arrangement of the figures outrages all accepted rules of artistic treatment, That of ‘Honour’ is the only one which can be seen from all sides, but from her attitude it is obvious that it is only intended to be viewed from the front; its character and vocation being problematical from all other parts, sometimes suggesting the idea to the irreverent multitude of a street acrobat throwing his four rings. The guardsmen can be seen only from the front – not the front facing the public thoroughfare, but that facing the vacant space between the Athenaeum and United Service Clubs, where nobody goes, except on purpose”.

The Illustrated London News article continues in a similar vein for several more paragraphs – they really did not like the new monument. These views were common across many other newspaper reviews of the Guards’ Memorial, for example, from the Illustrated Times on the 4th May 1861:

“Our monuments are unfortunate. In the vacant space between the Athenaeum and the United Service Clubs in Waterloo-place, stands the ‘Guards’ memorial’ and it may be doubted whether anything more incongruous in design can be discovered in the metropolitan streets. The principal figure – if the figure of ‘Honour’ which surmounts the pedestal may be called the principal when the others consist of three massy Guards in their great coats and bearskins – although it may be well proportioned, stands at an attitude at once ungraceful and dubious, while the wreaths which adorn the hands and wrists are held out as though they were a species of circular dumb-bell of considerable weight, and requiring some muscular exertion to extend at the requisite angle.

It is painfully evident, too, that the whole monument is only intended to be seen directly from the front – a fatal mistake in street sculpture, and one which utterly disfigures one thoroughfare for the sake of another,

With respect to the pedestal, it is like nothing in the world, and the palpable ill-combination of sculpture and building (not architecture) has an effect absolutely painful”.

Criticism of the monument was not just limited to the sculpture, plinth and setting, but also how the inscriptions were written. From The Atlas on the 24th November 1860:

“Unfortunately, as though to convince the world how necessary are competitive examinations, the military committee have drawn up inscriptions, in which the laws and maxims of the English language are violated and by which a great scandal has been proclaimed against the heroes of the Crimea. ‘To those who fell by their companions.’ In aiming at the epigrammatic, the author has descended in nebulas infernas. Would it have been too much trouble to have added ‘by the side of’, and thus saved the honour of those to the memory of whose glorious achievements this monument forms a cruel though unintentional charge?”

There were even questions in the House of Commons regarding the text on the memorial:

“Mr JAMES asked the First Commissioner of Works what was the meaning of the figures inscribed on the Guards’ memorial in Pall-mall, which seemed to mix together the masculine and neuter gender.

Mr COWPER sad the inscriptions were temporary, and could be removed. Perhaps the remarks of the hon. gentleman would be useful to the gentleman who had charge of that monument”.

Those responsible for all aspects of the Guards’ memorial must have been thoroughly depressed after reading all the newspaper reviews which seem to have been highly critical of all aspects of the new memorial – design, architecture, construction, location and inscriptions.

Many of the criticisms regarding the location of the monument were about the direction that the main figures of the monument were facing. The longer approach to Waterloo Place is along Regent Street St James from Piccadilly, and this approach road offers a view down to the location of the monument, however it is the rear of the monument we see from this approach.

The following photo is a view of the rear of the monument. Colours look a bit weird as the sun behind the monument caused the detail to be too dark so some extreme processing was needed.

The plaque on the rear of the monument states “To the memory of 2162 Officers, Non-Com Officers and Privates of the Brigade of Guards who fell during the war with Russia in 1854, 5, 6. Erected by their comrades”.

The side panels on the monument are shields recording the names of battles at Alma, Inkerman and Sebastopol.

Plaque recording how the monument was funded (which strangely states that it was erected in 1867 despite all newspaper reports of the Guards’ memorial being in 1861):

This is the view from alongside the monument, looking up along Regent Street St James towards Piccadilly, and illustrates why those writing when the monument was completed in 1861 claimed that it was facing the wrong way as when travelling down this street, you would see the rear of the monument.

Base of lamp post, installed at the same time as the Guards’ memorial.

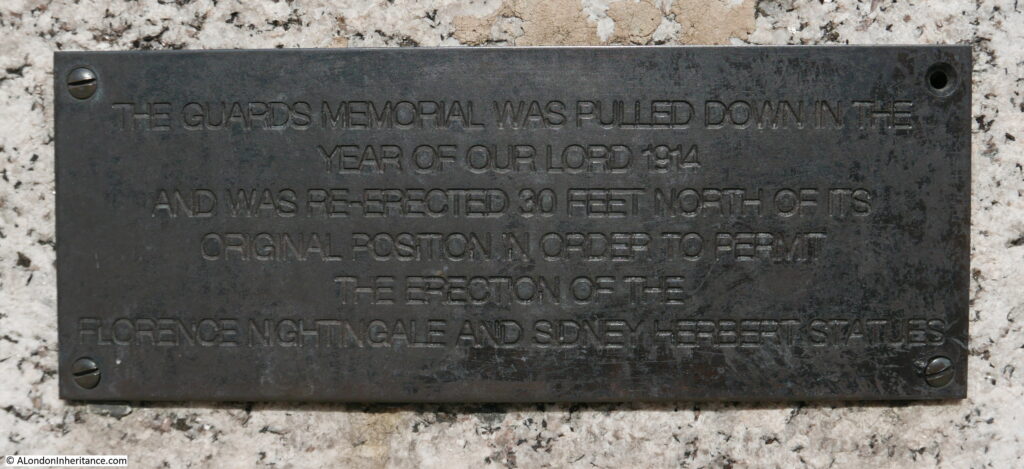

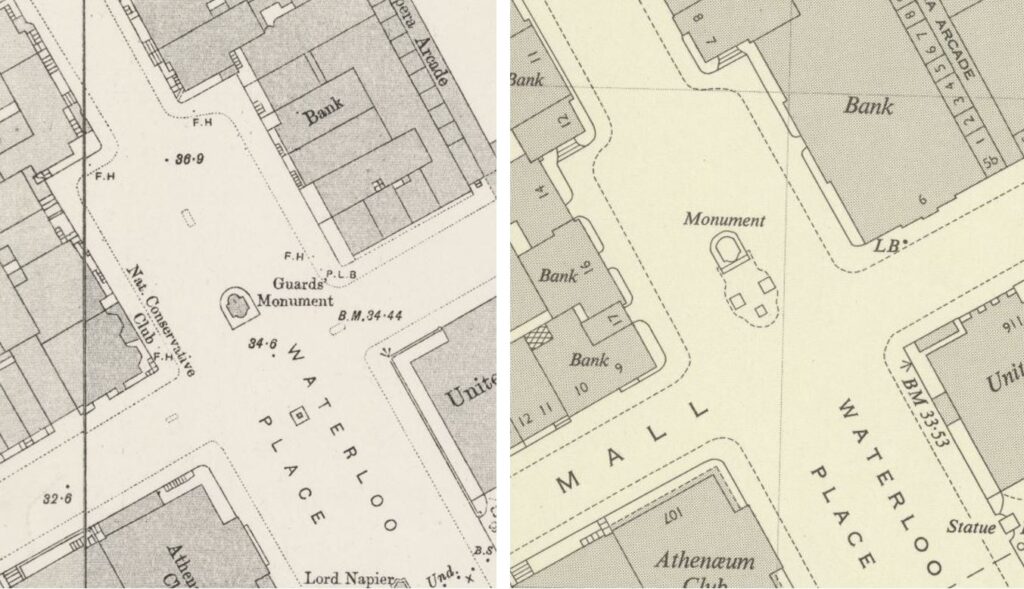

After unveiling in 1861, the Guards’ memorial stood in Waterloo Place alongside Pall Mall, exactly as designed by John Bell, however changes were to come and in 1914, the Guards’ memorial was pulled down and re-erected 30 feet north of its original position, to allow the installation of two new statues.

The change in position can be clearly seen in these before and after Ordnance Survey maps (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’).

Which means that we can finally come to one of the two new statues that was described in the newspapers of 1915 as the “First Public Statue of a Woman in London” – the statue of Florence Nightingale:

Florence Nightingale came to public prominence with her work in the Crimea and at the military hospital at Scutari. The conditions for wounded soldiers taken to military hospitals were appalling and more died of disease than on the battlefield.

Her work, along with the rest of her team of nurses in the Crimea would greatly improve conditions for wounded soldiers, and she is credited with turning nursing into a profession, and following her return from the Crimea published “Notes on Nursing” in 1859, and was instrumental in promoting the training of nurses and the better design of hospitals for the rest of her life.

The proposal for a statue of Florence Nightingale was made at a public meeting in the Mansion House in March 1911. At the same meeting it was also proposed to create a fund that would give annuities to trained nurses who had been unable to provide for old age or infirmity. A total of £4,000 was provided for the creation of a Trained Nurses Fund and six nurses were immediately identified as needing help.

The funds were mainly raised by many small donations from nurses, soldiers and sailors.

The panel on the front of the pedestal shows Florence Nightingale standing at the doorway to a hospital as wounded soldiers arrive.

The new statues were unveiled with very little ceremony. On a chilly February morning in 1915, two workmen put a ladder up against the statue to pull of the covers:

Newspaper reports of the Florence Nightingale statue were much more appreciative than those of the original Guards’ memorial. A typical syndicated newspaper report from the 24th February 1915 read:

“A NATION’S GRATITUDE – BRITAIN PAYS HONOUR TO FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE. Without ceremony the statue raised to the memory of Florence Nightingale will today be privately unveiled. The event is of special interest at a time when the sailors and soldiers, fighting for the country’s very existence, are reaping the fruit of the great work set on foot by Florence Nightingale. The statue has been erected in Waterloo Place, London, by the side of Foley’s statue of Sidney Herbert, with the Crimean Guards’ memorial a few yards in the rear, the whole forming an interesting and imposing group.

It was the suggestion of Lord Knutsford that Florence Nightingale’s statue should be placed alongside that of the man through whose instrumentality she undertook her great Crimean mission and by whom she was supported, and that two figures prominently associated with the Crimean War should be brought into close proximity to the Guards’ memorial”

There were however some negative comments about the low-key way in which the statue was revealed. A typical letter is from a Mary E. Pendered in the paper “Common Cause” (a weekly paper that supported the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies):

“MADAM – I was truly astonished to see your acquiescence in the insult to Florence Nightingale, for it was surely an insult to that great woman to let her statue be unveiled at 7.30 a.m. by a workman; and not only to her, but to all the nursing profession which she founded, if not to womanhood in general. There could have been no better time to raise as demonstration of the national homage to one who served her country so splendidly than the present, when our nurses are so valiantly doing their duty at the front, and are acknowledged by all the world as a valuable part of the army’s organisation. It is amazing and it is enraging to find that such an opportunity as this should have been missed”.

Inspecting the new statues in April 1915, a couple of months after they were unveiled:

The second statue unveiled early the same morning in February 1915 was the one on the right in the above photo, a statue of Sidney Herbert:

Sidney Herbert, or 1st Baron Herbert of Lea was the Secretary of State for War during the Crimean War.

He had known Florence Nightingale when along with his wife Elizabeth, they had met in 1848 whilst travelling in Italy. Elizabeth Herbert was one of the governors of the Establishment for Gentlewomen During Illness where Florence Nightingale had her first professional nursing job.

Following growing public anger at the conditions of military hospitals in the Crimea, Sidney Herbert commissioned Florence Nightingale to go out to the Crimea and lead nursing efforts.

Herbert’s statue was originally installed in front of the War Office in Pall Mall, however following the demolition of the building, it was relocated to stand adjacent to that of Florence Nightingale within the overall Crimea memorial cluster.

The plaque on the plinth of Sidney Herbert’s statue again shows an image of Florence Nightingale standing in the door of a hospital watching over wounded soldiers.

The claim that this was the first public statue of a woman in London was made in numerous newspaper reports in 1915 (apart from Royalty), the reports were not syndicated (an early version of cut and paste the same report into different newspapers), so many different papers made the same statement in their own words.

After this post was published, I received a comment from Joanna Moncrieff of Westminster Walks that the first was actually a statue to Sarah Siddons at Paddington Green, and that her statue was unveiled in 1897, which would put it 18 years earlier than Florence Nightingales statue.

No idea why the 1915 papers made the claim regarding Florence Nightingale’s statue. Perhaps they were unaware of the Siddons statue, or perhaps they considered Paddington Green as outside central London, the City to Westminster area.

One hundred and three years later, it is still unfortunately a headline when a similar event occurs and in 2018 a statue of suffragist leader Millicent Fawcett was unveiled as the first statue of a woman in Parliament Square.

I photographed the statue with the continuous flow of people wanting to see and photograph the statue soon after unveiling.

In a link between Florence Nightingale and Millicent Fawcett, the statue of Florence Nightingale was a focal point for the suffragist movement. In May 1915, the suffragist newspaper Votes for Women included the following article:

“Wednesday in this week being the anniversary of Florence Nightingale’s birthday, an interesting little ceremony, arranged by the Women’s Freedom League, will take place that afternoon after we go to press. Some ten or twelve Suffrage Societies are sending representatives, including Mrs Ayton Gould from the United Suffragists, to lay wreaths on the newly-unveiled Florence Nightingale statue in Waterloo Place.

Owing to the somewhat incomprehensible opposition of the authorities to any demonstration in memory of a woman whose name should be revered in every British family just now (which led to the secret unveiling of her statue by a workman at 6 a.m. on a wet winter’s morning), no speeches or procession will be allowed.

But perhaps this silent tribute to her memory will not be out of keeping with what we know of this great woman’s hatred of publicity; and the speeches will be made afterwards in the Essex Hall at 8 p.m. where a meeting will be held, also under the auspices of the W.F.L, who are to be congratulated on having arranged this commemoration as so appropriate a moment in our history”.

If you are ever in Waterloo Place, take a look at the Crimea memorial complex, and consider the difficulties in designing a monument and getting the location right, along with the sacrifices of those who died in the Crimean War.

Also appreciate that after Sarah Siddons, you are looking at what should have been reported in the papers of 1915 as the “Second Public Statue of a Woman in London” – unless you know any others?

Interesting stuff – thanks. It is a usually peaceful spot amid all the nearby traffic that I have visited often, yet was unaware that the Florence Nightingale statue was a first. With luck, I look forward to walking through the area once again in the summer months.

Having last night told those on my virtual tour around Paddington that the statue to Sarah Siddons on Paddington Green was the first statue to a woman who wasn’t a royal I got a bit of a shock when I saw your headline! It does seem odd that all the papers claimed that the Florence Nightingale statue was the first as Sarah Siddons’ statue was unveiled on 14th June 1897 and reported in the press too.

Separately thank you for including the wonderful newspaper reviews. I love them!

Joanna, I did wonder if it was really the first however the same statement was made in several newspapers, in different ways (so not a syndicated article). I will update the post. Thanks for letting me know.

Absolutely fascinating. Thank you so much!

It’s an eye-opener to read how critical and mocking the papers were about the Guards monument. I suppose public war memorials on that scale were themselves a novelty at the time. Hard to imagine someone mocking a war memorial in quite such a snide way now? The dignified statues of young guardsmen would have brought comfort to the bereaved at the time (and the “Honour” figure is no different from corresponding Roman images).

Wonderful to see the workmen uncovering the Florence Nightingale statue, and then to read the reactions. Thank you for all the work you’ve done finding all this out…really enthralling.

Another Victorian female statue ( royal, sort of) was Boudicca/ Boadicea.

I would never argue with the expert but I do believe the state of Boudicca near Westminster Bridge was erected in 1902 – what a woman!!

Statues represent both the subject & their times and the values of the times in which they were erected.

A statue of Boudicca erected closer to the time of her demise might have reflected the fact that she had most of the City of London burned & the survivors crucified – depending of course on who was putting it up.

Great read very absorbing.

You’ve provided such a remarkable context regarding the specific times in which these statues were erected, the varying meanings with which they were invested by different groups, and how they were received both then and subsequently.

Great investigation, and a fascinating portrait of the politics and culture(s) of our city as they are manifested in these examples of the built environment in which we live, both as individuals and as a community.

Thanks again!

I’m curious about the initials on the base of the 1861 lamp post. They look rather like an S and three Cs, intertwined with a large F. What do they stand for? Are they the initials of a gas company that erected the lamp posts (bearing in mind that 1861 was before electric street lighting)? Are they the initials of the local parish or vestry? Or what?

There appears to be a little more to the story of Sarah Siddons’ statue.

https://londonist.com/london/history/sarah-siddons-statue-paddington-restored

If you are looking for a statue of a named historical non-royal woman, so queens regnant or consort and nymphs or other fictional or allegorical figures are out, then I think Siddons is the first in London.

Boudicca (with her daughters) in Westminster was installed in 1902. She is a real person but arguably royal.

Which I think means the second is the memorial to Margaret MacDonald in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, unveiled in 1914, which includes a depiction of the woman herself in a protective pose, with her arms outstretched around some children. As it happens, a decade and a half later, her husband became the first Labour prime minister.

So Nightingale by Pall Mall would be the third.

More here: https://lilymaynard.com/the-mary-wollstonecraft-statue-everything-thats-wrong-with-modern-feminism/