During recent years the news has been coming thick and fast. Covid, Ukraine, political turmoil in this country with three Prime Ministers in a single year, inflation and the resulting cost of living crisis. Can 2023 be any better?

Based on the experience of recent years, it would be rather foolish to try and predict what will happen during the coming year, so I thought that for the first post of 2023, I would go back 300 years and look at what would happen in London during 1723. What was life like for Londoners, what could we have expected to see on the streets, what were the key events?

Using newspapers published during 1723, I have compiled a month by month review of events in the city. We will find books with titles such as “The Fifteen Plagues of Coffee and Tea“, we will discover the “Atterbury Plot”, meet “a notorious Strumpet and Procuress about Town” and also “Swangy Peggy“, look at trade in the Port of London, disease, illnesses and medical treatment, crime and punishment, how you could be imprisoned for the wrong words, and the strange sights to be seen across the city’s streets.

King George I was the monarch, Robert Walpole was the Whig Prime Minister. The artist Sir Joshua Reynolds was born in 1723, as was the Scottish economist Adam Smith who would go on to write The Wealth of Nations.

Apart from actions against Pirates in the Caribbean, the country does not seem to have been at war.

The starting point for a review of 1723 – a London year, will be:

January 1723

On January the 1st “was preached the Anniversary Sermon to the Societies for Reformation of Manners at the Church of St. Mary-le-Bow, by the Right Reverend the Lord Bishop of Gloucester; at which were present, the Lord Mayor, Sir Francis Forbes, Alderman, and also the Bishops of Sarum, Litchfield and Coventry, Carlisle, Peterborough and Bristol, with upwards of twenty of his Majesty’s Justices of the Peace for the County of Middlesex and Liberty of Westminster, and a considerable number of Reverend Clergy.”

Executions were a theme of the year. They were frequent, with Tyburn being one of the main sites, as described here: “Edmund Neal and William Pincher, who were condemned last Sessions for Robbing on the Highway, were executed at Tyburn.”

Such was the number of executions, that when there was a sessions period with no convictions it was considered news: “Tis remarkable that since the last Sessions, no Person has been committed to Newgate for the Highway, or any other Capital Crime, except a Woman for the Murder of her Bastard Child.”

One person sentenced to execution even had bets placed on whether the sentence would be carried out. We will come across this person a number of times during the year: “Several considerable wagers are again laid concerning Mr. Layer, some affirming that he will have a farther Respite, others, that sentence will be executed in him the 19th instant.”

The zoo at the Tower of London claimed a victim in January: “An Apprentice to Mr. Ushall, a Taylor in Bridges Street, Covent Garden, lies ill of some wounds he received from one of the Lyons in the Tower.”

Caroline of Ansbach was the Princess of Wales as she was married to the King’s son, the future George II. They lived in Leicester House, which was on the northern edge of what is now Leicester Square, which was mentioned in this report: “Her Royal Highness the Princess of Wales expecting to be brought to Bed about the latter end of this Month or the Beginning of the next, all the Servants appointed to attend her Royal Highness at that juncture, are taken into Leicester House.”

The Princess of Wales gave birth to a daughter, Mary, who would go on to marry Frederick II, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel. The marriage would not be a good one due to the abuse Mary suffered from Frederick. They would separate and Mary would continue to live in Germany, then Denmark.

1723 was not a good year to be heard criticising the King: “This Day, Mr. Ogden was tryed at Hicks Hall for Cursing the King, which was plainly proved, but some of the Evidence deposed that he had been very much in Drink, and that he was esteemed a Person very well affected to His Majesty, and often drank his Health. The Jury, after a short delay, brought him in guilty.”

In an article a week later it was recorded that Mr. Ogden has been “fined £50 and 3 months imprisonment”.

February 1723

Another example of why it was not a good idea to say anything bad about the King and Queen, or mention the “Pretender” (James Francis Edward Stuart, the Old Pretender, who claimed the throne for the Stuart line): “This Day, Mr. Cotton, was try’d at the King’s Bench for saying. ‘The Picture of the Pretender’s Wife, was the Picture of the Queen of England’; the Evidence against him was Mr. Pears, one of the King’s Messengers. The Jury brought in not Guilty.”

February 1723 saw the founding of one of the companies that would supply water to the growing city: “His Majesty has been please to order Letters Patents to be passed under the Great Seal of Great Britain, for incorporating the Governor and Company of Chelsea Water Works, pursuant to an Act of Parliament passed last Sessions, for supplying the City and Liberty of Westminster and Parts adjacent, with Water. And the said Undertakers are preparing Machines, and beginning to erect the said Works with all Diligence and Speed.”

A strange sight in one of London’s parks: “On Tuesday last a Soldier belonging to the Third regiment of Guards, was whipped in St. James’s Park and received 300 Lashes for acting as Assistant to a Bailiff, having his Regimental Clothes on. And on Friday he underwent the same Punishment again, and was afterwards drummed out of the Regiment.”

In 1723, convicts could be sentenced for transportation, and whilst Australia is normally assumed to be the destination, convicts could also be transported to the Americas, as this report demonstrates: “Yesterday Morning 40 Felons, convict were put on board a close Lighter at Black Fryers Stairs from Newgate, in order to be transported to Maryland.”

Sir Christopher Wren died in February 1723. Coverage of his death in newspapers at the time was rather brief: “Yesterday about Noon dy’d Sir Christopher Wren, aged about 92; he was formerly Surveyor General of the King’s Works; he built St. Paul’s Church, and all the Rest of the Churches since the great Conflagration.”

Newspaper’s in 1723 published lists of new books that had just been published, under the heading of “This Day is Published”. The list for one week in February 1723 has some rather strange titles and subjects:

The London Bawd, and the Character of a Common Whore; with her subtle and various intrigues to delude innocent youth into Hellish Snares. Written by one that hath been a Sufferer, and now makes this Publick for the Benefit of Youth that go up to London, or distant from their Friends, by way of Advice. Printed for the good of the Publick, and Sold by Booksellers of London and Westminster and by the Printers. Price Bound 8d.

The Ladies Golden Key: or a Companion for Men of Sense. Written by a Person of Quality. Price 3d.

The Parson and his Maid, a Tale. To which is added, Venus enraged, a Poem. Price two pence.

The Country’s Misfortune: Or the Cuckoldy Yeoman. With several delightful Poems to put away melancholy Thoughts of honest Men. Price Three Pence.

The Fifteen Plagues of Coffee and Tea, with a Female’s Satyr on Thin Bread and Butter. Written by a young Gentlewoman, who brought the Green Sickness upon her by Drinking those dull Liquors. Price Two Pence.”

Scientific and technical advances were being made, and put on display in London: “There is a new invention of a strange kind of Machine for Ploughing of Ground. The Work is performed by one Man, and without Horses; it is rekoned an extraordinary Piece of Ingenuity, and a great Number of Artists and Persons of Quality have been to see it. It is now at the Golden Ball at Hyde Park Corner.”

March 1723

To start the month of March, a report on one of the many strange sights to be seen in London in 1723 – “Last Monday Morning, one Brittain, a Widow in Milford Lane, was married to a Brewer’s servant at the Church of St. Clement Danes, who being advised, went to the Church Door without any other Apparel on besides her bare Smock, to the great Surprise and Sport of a numerous Crowd of Spectators. It seems, by this means, she thinks herself exempted from paying any debts contracted by her former Husband. At the Church Door her intended Spouse took her in his Arms, and carrying her to an Apothecary’s House over against the said Church, new clothed her completely; after which the Nuptials were solemnized.”

There was a rather public spirited Will, where: “One Mr. Rice, a Solicitor of Furnival’s Inn, who latterly died, has bequeathed £500 toward paying the National Debts. He owes it but a Mite; but he does it to set a good example”.

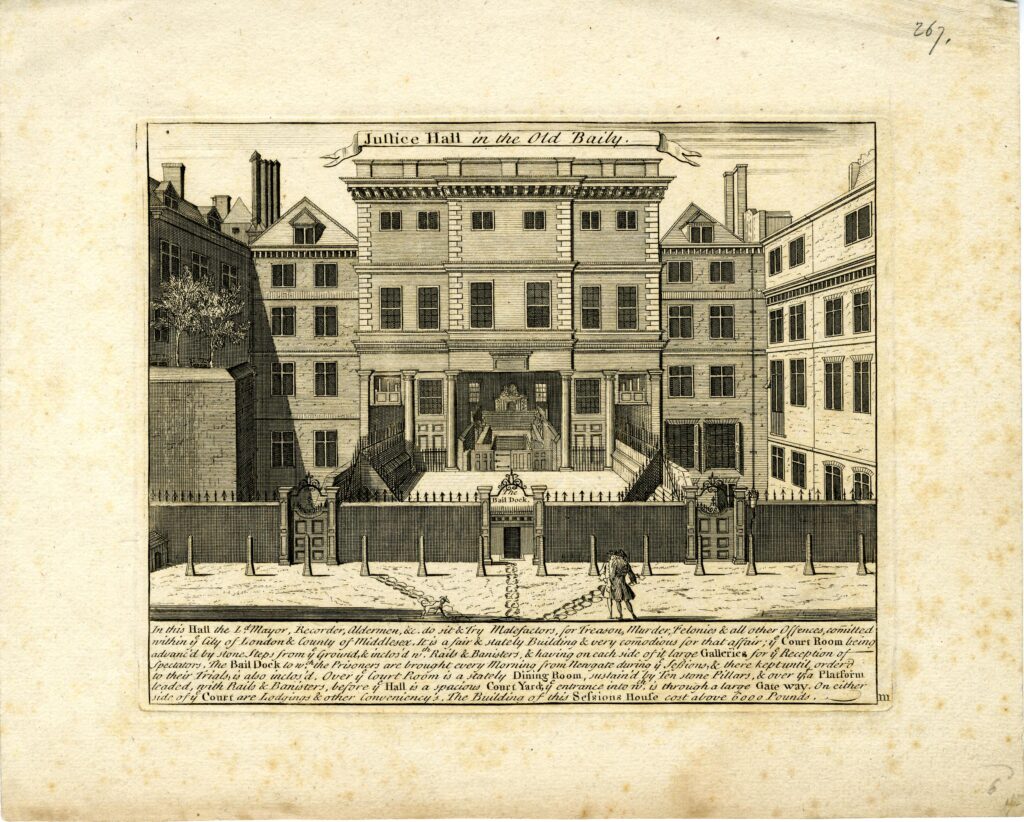

There was also another example of the horrific sentences handed out: “Last Saturday Night, the Session ended at the Old Baily, when the three following Malefactors received sentence of Death, viz. William Sommerfield and Willim Bourk for the Highway, and one Frost for stealing a Horse from the Post Boy belonging to the Post Master of Sevenoak. Two were burnt in the Hand, viz one for Manslaughter, and one for Felony, and several others were ordered for Transportation.”

The Justice Hall in the Old Baily as it would have appeared in 1723 (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

In the first months of 1723, there had been many newspaper reports regarding a Mr. Christopher Layer and Francis Atterbury, the Bishop of Rochester. Both men were being held in the Tower of London following a plot in 1722 which aimed to restore the House of Stuart with “the Old Pretender” James Francis Edward Stuart, who was exiled in Rome as King.

The plot appears to have been the main political story of 1723.

The plot was exposed and Layer and the Bishop of Rochester were both held in the Tower and questioned as to their involvement and coconspirators. The plot was named the Atterbury Plot after the Bishop of Rochester, however although he seems to have played the leading role in the plot, it was Layer who suffered more.

“Layer, at his Examination before the Lords of the Council, confessed that being in Discourse with Lord Orrery, that Lord Orrery said that nothing would relieve the Nation, but a Restoration; and that he would be glad he could contribute to bring it about; that it must be done by Foreign Forces.

Lord Orrery told him, the Regent might be brought to wink at anything, but was too perfidious, that he was not to be trusted, and that the French had made a Tool of the Pretender.

Layer confirmed to the Committee upon his Examination in the Tower, that Lord Orrery declared himself constantly of Opinion, that nothing could be done to any Purpose in the Pretender’s Favour, without Foreign Forces.

The Council took under Consideration a Report, and revealed a destructive and horrid Conspiracy had been formed and carried on by Persons of Figure and Distinction, and their Agents in Conjunction with Traitors abroad, for Invading the Kingdom, with Foreign Forces and raising a Rebellion at Home; for seizing the Tower and the City of London; for laying violent Hands on his Sacred Majesty and the Prince in order to subvert our happy Establishment, by placing a Popish Pretender upon the Throne.”

The report states that in his examination, Layer tried to prevaricate and suppress the truth and conceal the conspiracy, however the examination of those involved in the Atterbury Plot did find other possible conspirators, including one John Plunket, and Parliament had the following rather ominous vote: “It was ordered in a Division, 289 against 130, that a Bill be brought in to inflict certain Pains and Penalties on the said John Plunket.“

We will find out what happened to Christopher Layer in a couple of months time.

April 1723

Given that the sentence of highway robbery was usually death, there is a surprising number of these crimes reported, for example “Last night between 8 and 9 a-Clock, a Hackney Coach returning to Town from Maidenhead, having a gentleman and two gentlewomen in it, was set upon a little beyond Tyburn by two Highwaymen, who robbed them of a considerable Sum of Money, two Gold Watches, and one Silver Watch.”

As well as highway robbery, in 1723 London was a very dangerous place where fatal accidents were a common occurrence, such as this tragic example “A sad Accident happened in Gray’s Inn Lane, where a Cart passing along, was stopped by some Gentlemen, who endeavoured to kiss a Woman that was in it with a Child; but in the Struggle, the Woman’s Arm was broke, and the Child falling from the Cart was run over and killed.”

In April 1723 there was an interesting example of fire fighting techniques in use at the time: “On Monday Morning, early, a Chimney at Leicester House was observed to be on Fire, and the Wind being very high, the Flames spread and threatened farther Mischief; so that the Prince got out of Bed, and ordered some of the Soldiers on Guard to be admitted in, to fire their Pieces up the Chimney; which they did accordingly, and within ten or a dozen Discharges, removed all Apprehensions of Danger, and his Highness gave them five Guineas.”

By the standards of today, the sights to be seen in London 300 years ago were often just bizarre and awful, such as this example from Hyde Park: “Yesterday, pursuant to his Sentence, the Deserter who was condemned by a late Court Martial, was shot in Hyde Park. He was conducted from the Parade to the Place of Execution by his whole Regiment (the Second of the Guards) with the Earl of Albermarle at the Head of them, and was at once made an End of, twelve Soldiers firing upon him together.”

Rumours of trouble on the international stage has always caused problems for the London Stock Exchange, and in April 1723 there was an example, when: “Last Thursday there was a Letter from Malaga, with pretended Advices that the Marquis de Lede was marching along the Coasts with some Spanish Troops as though they had formed a Design against Gibraltar. This Stockjobbing News had the Effect that the public Stocks fell considerably.”

May 1723

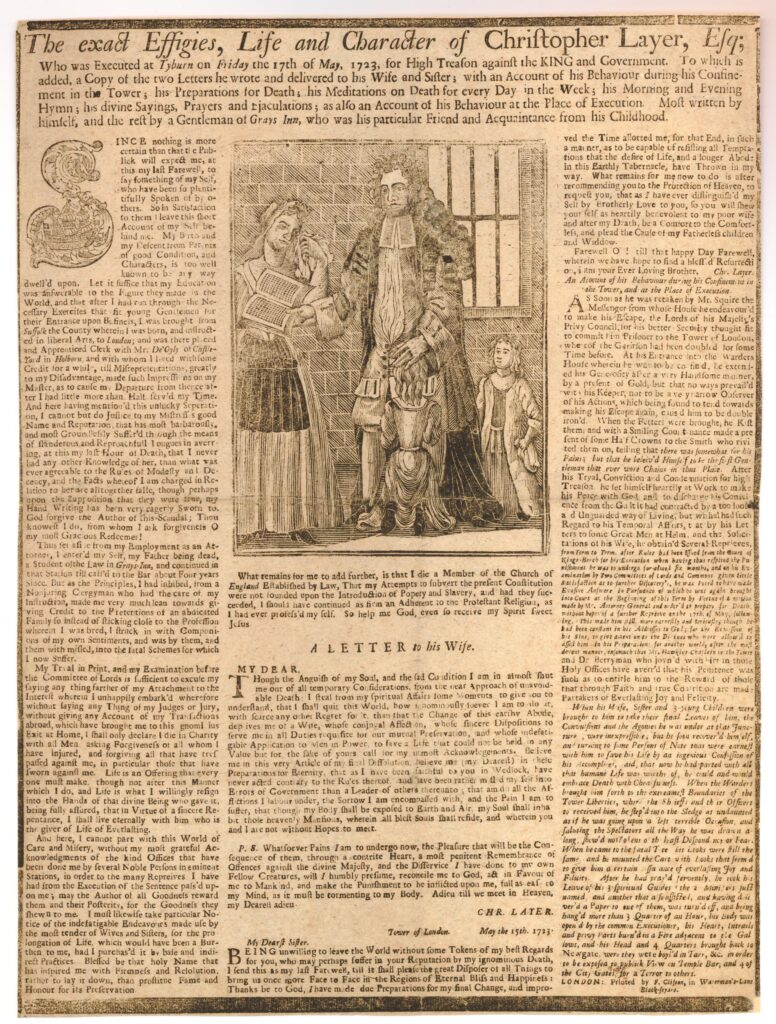

In May 1723, we find out what happened to Christopher Layer:

“Yesterday, about one a Clock, Christopher Layer was executed at Tyburn, pursuant to his sentence for High-treason. The Sheriffs having demanded him of the proper Officer of the Tower, he was delivered up accordingly; his Fetters being knocked off, he was carryed under a Guard of Warders and Soldiers through the little Guard-room, over the Draw-bridge to the wharf, from whence he walked to Iron Gate, near St Katherine’s, in the County of Middlesex, where he was received by the Sheriffs Officers, and carryed upon a Sledge drawn by 5 horses, to the place of Execution, where he was attended by the Rev. Mr. Hawkins and the Rev. Mr. Berryman, who assisted him in his Devotions.

The populace on this occasion was very numerous, many Scaffolds were erected in the Way, for the Advantage of the Spectators, some of which were broke down, by which Accident many were bruised. At the Place of Execution, he behaved himself with great Composure of Mind, and seemed very unshaken, frequently affecting a Smile, nor did he appear shock’d even in the Article of Death. He had in the Cart with him some Gentleman who were his friends, to one of whom he gave a paper, and another to the Under-Sheriff.

Silence being made among the People, in Expectation of his making some Speech to the Company, he in some measure disappointed them, only saying that he had left behind him in Writing, the true Principles of his Religion, that Religion in which he died and that he hoped no Body would publish any Thing injurious to his Fame, and Reputation after he was dead, and that the good people of England might expect, but expect in vain, to see happy and flourishing Days in Great-Britain, till the fortunate Hour was come, that they saw a certain Person was brought over into the Nation amongst us.

Afterwards his Head was severed from his body, and sent to Newgate to be prepared in order to be fixed up this day at Temple-Bar, but his quarters were delivered to his Friends, who put them in a Hearse, and brought them round about Kinsington to Mr. Purdy’s, an undertaker in Stanhope-street, Clare-Market, who had them sewed together, in order to be interred in Cambridgeshire. His whole Deportment, both in his Passage and at the Place of Execution, was manly and intrepid.”

A broadsheet from 1723 showing Christopher Layer and recording his life and character (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

June 1723

In June 1723 “The Anniversary of the happy Restoration of King Charles II, and the Royal Family, was celebrated here with the usual Solemnity.”

In 1711 an Act of Parliament established the “Commission for Building Fify New Churches”. This was a response to the growing population of London, and how London was expanding to areas where there were no, or very few, churches to serve the population. The Commission never achieved the total number of fifty, but in 1723 progress was being made on a couple of the churches: “The Commissioners for Building the Fifty New Churches, met on Monday last at their Office in Palace Yard, and agreed to the Proposals from Plumbers, Joyners, &c. for finishing two more of them, viz. that of St. Mary Woolnoth in Lombard Street, and that in Hanover Square. And we hear that the £20,000 in the Treasury raised for building the said Churches is to be applied to finish these two, and the two others at Deptford and in the Strand”.

St. Mary Woolnoth was not really a new church, rather a rebuilding of an existing church. The church in Hanover Square is St. George’s. The church in Deptford is St. Paul’s and in the Strand is St. Mary-le-Strand.

Coffee seems to have been a popular drink in London in 1723, however: “Tis remarkable, that there is much more Coffee sold here in Town than the Quantity fairly imported.”

Also, in London in June 1723: “We hear that an Information has been given against one Larchin, a notorious Strumpet and Procuress about Town, for decoying several Servant Maids from their Masters, in order to become Prostitutes.”

Although Christopher Lavery was executed for treason for his part in the Atterbury Plot, Francis Atterbury, the Bishop of Rochester was given a more lenient sentence as he was banished from the country, and in June: “There’s Advice that on Friday morning last, the late Bishop of Rochester landed at Calais, and will set out in a few days to the Austrian Netherlands. The Opinion of some People is so hard against the Gentleman, as to think when he is in Foreign parts, will change his Religion, although he mentions in his speech before the Lords, that he had wrote and preached, from his infancy in Defence of Martin Luther, and declares with the strongest Asseveration, that he will burn at the Stake, rather than depart from any one material Point of Protestant Religion, as professed in the Church of England.”

On June 15th, the Bishop of Rochester’s possessions were sold, raising almost £5,000, which appears to have be retained by the State.

July 1723

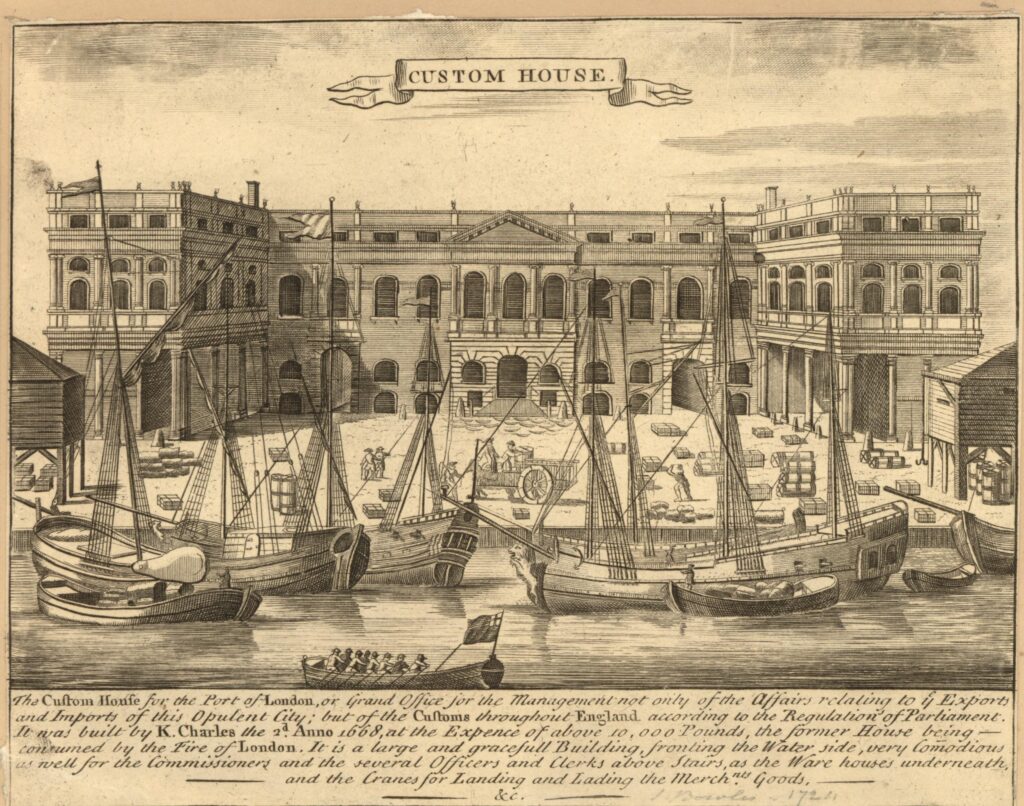

Newspapers carried reports of the goods that were imported and exported through the London Docks. For the period of the 13th to the 25th of July, 56 ships arrived in the Port of London carry goods and the following tables lists the goods imported, and from where:

Interesting that the majority of London trade appears to have been with Europe, with Holland being a major source of imports into the country. I assume the ports to the west of the country such as Bristol and Liverpool dealt with trade to and from the Americas and the rest of the world.

I had intended to run through all these and list what many of these goods were, as some of the names are not obvious, however I ran out of time. Perhaps a subject for a future post to look at early 18th century imports and exports through the Port of London.

The Custom House in the City would have played a key part in ensuring the appropriate customs were paid on imported goods (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

August 1723

The “South Sea Bubble” was an event that took place in 1720 when the share price of the South Sea Company rocketed to very high levels before collapsing. This caused severe problems within London’s financial markets and caused a number of bankruptcies among the owners of shares in the company. An investigation into the collapse found that there was widespread fraud, and that many of the Directors of the company were involved in fraud. The Directors were sacked, and received heavy financial penalties, and in August 1723 it was reported that: “The several Appraisers employed by the Trustees of the Forfeited Estates of the late South-Sea-Directors, are now paid off; and we are assured that some of their Bills amounted to Five Hundred Pound each.”

However the South Sea Company was still trading, and would continue to do so for many years, as also in August 1723: “The South Sea Company’s Warehouses are at present full of our Woollen Manufacturers, to be sent on board their Assiento Ship, now fitting out at Blackwall.”

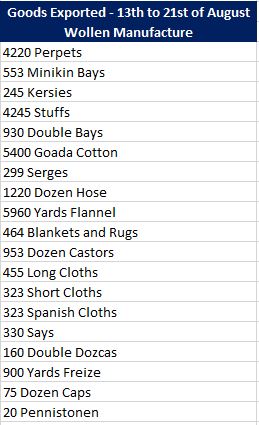

The mention of the South Sea Company’s warehouses being full of woollen products was not a one-off as woollen products were a considerable export from London. Tables in the papers of imports and exports also included a special table dedicated to woolen products, and between the 13th and 21st of August 1723, the following were exported from London:

Whilst some of these products have recognizable names, I have no idea what many of them are, for example a Perpet or a Minikin Bay in the first two lines of exports. What is clear though is that a considerable volume of woollen products were being exported through the London docks in 1723.

The statue of Charles I, which still stands in Trafalgar Square, was, in August 1723: “The Pedestal on which stands the statue of King Charles the First on Horseback at Charing Cross is repairing and beautifying at the Expense of the Government, and will be defended for the future by a Wall, breast high, with Iron Rails upon it.”

Fallout from the Atterbury Plot was causing concern within the City of London due to the impact it had on the freedom of the individual with the suspension of Habeas Corpus and the ability of the Government to imprison the individual at will: “The detestable Conspiracy which occasions the present Suspension, having been discovered and signified to the City of London, about Five months since, and diverse imprisoned for a considerable time past, we cannot conceive it to be highly unreasonable to suppose that the danger of this plot, in the hands of a Faithful and Diligent Ministry, will continue for a Year or more yet to come; and that in to high a degree, as to require suspension of the Liberty of the Subject (for so we take it to be) during all that Time.

His Majesty having not visited his Dominions Abroad these two last years, will very probably leave the Kingdon the next Spring to that End, in which case, this Great Power of Suspecting and Imprisoning the Subject at Will, and detaining them in Prison till the 24tgh of October 1723; and for as much longer time, till they can after that take the benefit of Habeas Corpus (if they can still do it at all).

September 1723

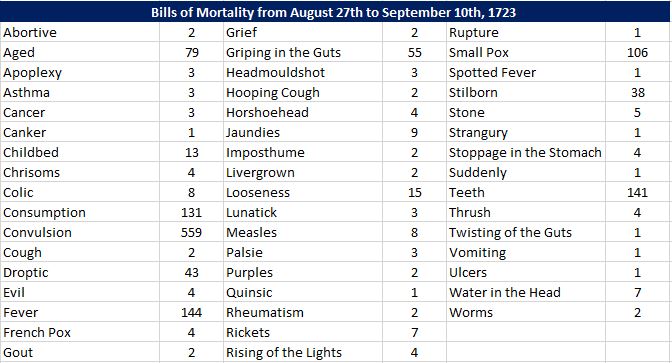

London in 1723 was an unhealthy city. A considerable range of disease and illness stalked the densely populated streets, and death rates were high. The churchyards and crypts of the city’s churches were not pleasant places as they were frequently overcrowded with burials

Medical care was rudimentary at best, even for the wealthy, and for the poor was almost non-existent.

Childbirth was a dangerous time for women and babies, and the death rate for young children was very high.

The following table is the Bill of Mortality for the period from August 27th to September 10th, 1723 and shows the numbers and causes of death.

Many of the causes of death are recognisable today, however there are many strange causes. I wrote a post examining Bills of Mortality and the meaning of many of these names in this post.

In the same period, there were the following casulties in addition to the above:

- 3 – Drowned in the River Thames at St. Paul at Shadwell

- 2 – Found dead at St. Margaret Westminster

- 1 – Murdered at St. Olave in Southwark

- 1 – Broken Leg

- 6 – Overlaid

In the same period there were 735 Christenings, 1466 Burials, and the increase in burials over the previous period was 29.

October 1723

The military had a significant presence in London during 1723, probably due to the perceived threat of a Jacobite rebellion, and plots such as that by Atterbury, the Bishop of Rochester. It must have been common to see soldiers on the streets, and there are many reports of soldiers getting into fights. There was a large military encampment in Hyde Park, as reported: “Yesterday the Right Honourable Earl Cadogan was present in Hyde Park and saw the Grenadiers perform an exercise of throwing Grenades. the Cavalry there decamp next Monday, but the Infantry are to hut, and the Artillery is to remain with them.”

As well as Hyde Park, temporary quarters were required across the city, and in October the following was issued, which cannot have been very popular: “On Tuesday, a Warrant was sent to the High Constable of the City and Liberty of Westminster, requiring him to order his Petty Constables to make a Return of all the Inn-keepers in the said Liberty, for the Horse Guards to quarter in their Inns.”

London seems to have been a rather tense place to be if you were not seen to be loyal to the King and Government, for example: “A gentleman of the Temple being under Apprehensions of a Visit from some of his Majesty’s Messengers, borrowed a horse of a friend for the day, under pretence of going out one Afternoon to take the Air, but has not thought fit to return since. A Brother of his, who had not to much presence of Mind, is seized with his papers.”

The various plots against the King, whether real or not, the crime of speaking out against the King and similar crimes led to a number of people being imprisoned in the Tower for Treason, and investigations would include their family, so: “We hear that the Lady of Counsellor Leare, now Prisoner for High Treason in the Tower has been seized coming from France, being ignorant of the Fate of her Husband, and having about her several Letters of great Consequence.”, and;

“On Thursday morning last, the Right Honourable Charles Boyle, Earl of Orrery, one of her late Majesty’s Privy Council and Knight of the most ancient Order of the Thistle, being brought to Town in Custody, from his Seat at Brittel in Buckinghamshire, was the same Evening examined before a Committee of Lords at the Council at the Cock Pit, and ordered to be confined in his own house, with a Guard of 30 soldiers; and last Night, being examined again, his Lordship was, between 10 and 11 o’Clock, committed to the Tower, under a Guard of Centinels.”

The Tower of London as it would have appeared in 1723 (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

November 1723

The things you would see across the streets of London in 1723 are so very different to today, and there are plenty of examples in the newspapers of 1723, such as the following from November: “The Company of Surgeons having a Warrant for receiving the Body of one of the Malefactors that were executed on Wednesday last at Tyburn; the Mob happened to be appraised of it, and assembling together in a riotous manner, carried it off, and afterwards begged Money about the Streets, in order to give it, as they pretended, a decent Interment, but when they had finished their Collection, they flung the Body at Night over the Wall into the Savoy Church Yard. Next Day the Officers of the Parish sent to the Surgeons to know if they would have him, intending otherwise to bury him there.” This was one of three executions carried out at Tyburn on the same day.

In the early 18th century, travelers had problems with overcharging when they travelled along the river or the street, with Watermen and Coachmen using a number of tricks to overcharge. There were regulations to prevent this, and in November; “A Hackney Coachman was committed to Newgate by the Commissioners for Licensing Hackney Coaches and Chairs, till such time as he pays the Fine imposed on him for demanding more than his Fare.”

Medical care in 1723 was very basic, and many treatments were still in their infancy. Dropsy was the name given to the condition whereby excess fluid in the soft tissues of the body would cause swellings. The treatment in 1723 would be to “tap” the infected area where a metal tube was inserted into the body in an attempt to drain off the fluid. A process which could take several days, but was not that successful as shown by this report; “Last night died Sir Thomas Palmer, Bart. at his lodgings in Bow Street, Covent Garden, of the Dropsy, after he had been tapped the Day before for the same; he was member of Parliament for Rochester in Kent.”

Small Pox killed a large number of Londoners during the early 18th century, and prevention would have to wait until after 1796 when Edward Jenner discovered how to create and administer a Small Pox Vaccine. Prior to Jenner’s discovery, a method called “variolation” was used, where people who had not had the disease were exposed to material from smallpox sores from those infected. This method had limited success as this report tells: “We are informed, that the eldest son of Mr. A’Court, member of Parliament for Hatchbury, is dead of the inoculated Small Pox; but Miss Rolt, a young Lady of great Fortune, who was also inoculated is happily recovered, though with the utmost Hazard of her Life.”

Londoners were also frequently informed of the strange medical events taking place across the country. These reports probably had some grain of truth, but had been exaggerated many times, so for example, in November 1723, Londoners would read; “They write from Devizes in Wiltshire, that a Tradesman’s Wife of that place, after a Labour of 4 Days, was delivered of a Monster, which has one Body by two Breasts, an Head of an exorbitant size the Eyes distorted, two Teeth, a flat appearance of a Face in the Nape of a Neck four Arms, Hands, Legs and Feet, with 6 fingers and toes on each. But what is most remarkable is, that the side to which the Face pointed, was Male, the other Female; The Male had nails upon the fingers and Toes, which the Female had not.”

Londoners could also look up to the night sky in November 1723, and see “the Comet so much spoken of, was seen plainly on Monday Night last, notwithstanding it was the Opinion of the Persons skilled in Astronomy, it would have disappeared some Time ago.”

But be careful when looking up as you could fall victim to this type of crime; “A Woman of the Town who goes by the Name of Swangy Peggy, was last Tuesday Night committed to the Compter for picking a Gentleman’s Pocket of 50 Guineas.”

December 1723

A consequence of the Port of London being a key part of the city’s commercial activities were the many reports in newspapers covering shipping bound for London, and the frequent loss of a ship, so in December 1723 we find examples such as “The Phoenix, Captain Olding, bound from Petersburg to London was latterly lost near Yarmouth.” and: “The Fyfield, Captain Swinsen, bound from South Carolina to London was drove ashore on Wednesday last near Margate, and lost. The men were all saved, but Captain Swinsen , stepping into the boat, unfortunately fell into the sea, and was drowned.”

There were a number of charitable institutions across the wider London area that took in elderly people, however they usually had strict criteria covering who could benefit, so in December 1723, the Trustees of Sir John Morden’s College in Blackheath were “about to increase the Number of Pensioners on that Foundation: None but decayed Merchants who are 50 year of age, and Communicants in the Church of England are capable of being admitted.”

The Catholic threat to the monarchy was in the background throughout 1723. There was an expectation that Catholics would swear an oath of loyalty to the King and the country, however there were many ways to get around this, as this report explained: “We are informed that divers Papists and others, who had resolutely determined not to take the Oaths, have been personated in several of the Courts, by their Agents, who have Sworn, in the Name of the said Papists, &c recorded, as though they actually complied with the Terms of the late Act of Parliament.”

As today, foreign ambassadors were based in London, where they could interact with the Royal Court, Parliament, the City, Merchants and Financial institutions. Newspapers frequently recorded their activities and visits, and in December: “The Morocco Ambassador went to the Tower, where he was well received by the Officers, and shown the Curiosities and Rarities there, with which his Excellency was well pleased and gratified the inferior Officers that attended him.”

London continued to be a place of almost casual accident and death, such as “On Monday last, several Porters in handling a Hogshead of Tobacco on Shipboard at Wapping, unfortunately let go their Hold, and the Hogshead rolled down the stairs at waterside, into a boat, in which was a little boy, who was dashed to pieces, as was likewise the boat.” These stories are simply reported as fact, without any criticism of the conditions that enabled such an accident to happen, or a call for safety improvements.

Trials of those who supported the Jacobite cause, or who raised any actions against the King continued through the year, including in December, when the trial of the leaders of a riot in Cripplegate in July, came to the Old Bailey: “The evidence for the King deposed that on the evening of the 23rd of July, a great Mob armed with Clubs, Staves and other unlawful weapons, assembled at Cripplegate, and broke the windows of Mr. Jones, an Apothecary, and afterwards attacked the Crown Tavern and Coffee House, demolishing the windows and wounding several Persons who endeavoured to defend themselves at the House. They likewise deposed that though the Proclamation was read three Times, the Mob did not disperse, but continued in a Tumultuous Manner, crying No King George, No Hanover Proclamation, Down with the House.”

And that ends a brief run down of what life in London was like during 1723. A very different city to the one we experience today, although there are some themes which we can recognise, and the names of city locations provide a familiarity across the 300 year gap.

Whatever 2023 brings, I wish you a very Happy New Year.