In August 1953, my father was cycling / youth hosteling around Somerset, as part of his post National Service trips with friends around the country. One of the places visited was the City of Wells in Somerset, and this is his photo of Wells Cathedral:

Seventy years later, and the view is the same:

Apart from the loss of a couple of chimneys to the right of the Cathedral, the view has not changed, not really surprising given the age of the building and its significance. The only feature that will confirm the top photo dates from 1953 are the clothes worn by the people at the very bottom of the photo.

There are a couple of minor changes and restorations to the façade. For example, in 1953, some of the niches at the top of the central part of the façade were empty. Today, there is a statue and carved objects in these niches:

Wells is a smallish town in Somerset, not that far to the north of Glastonbury. The town’s status as a City dates back to the medieval period and the importance of the Cathedral. This was formally recognised in 1974 when Queen Elizabeth II confirmed city status on Wells.

Evidence of a Roman settlement at Wells illustrates the long history of the place, and the name provides a clue as to why people would want to settle here, and why the city has such a significant Cathedral.

Wells takes its name from wells that can still be found, wells that seem to provide an almost continuous flow of large amounts of water, and water makes it presence known across the city, including along the High Street and the Market Place where channels of water flow between the road and the pavement:

The Market Place today is today mainly lined with shops and cafes targeting visitors, however there were a large number of locals in the cafes during our visit. The Market Place, with the towers of the Cathedral in the background, does look like the dream location for a tourism advert, but it has not always been so peaceful.

After the Monmouth Rebellion, in 1685, Judge Jeffreys held what were known as the Bloody Assizes in the Market Place and condemned 94 people to death for supporting the Monmouth rebellion. Judge Jeffreys would later be found hiding in Wapping, where he was recognised by someone who had the misfortune to come up before him. See this post for the story.

Even if you have not been to Wells, you may find some of the places in the city familiar. Wells was the location for many of the exterior scenes of the film Hot Fuzz by Edgar Wright (who grew up in Wells) and Simon Pegg.

The Cathedral was digitally removed from the film, but many other locations are recognisable, including the pub, the Crown at Wells (or Sandford as the town was named in the film):

View looking back along the Market Place, close to the entrance to the Cathedral. The board in front of the bin advertises both a Heritage Walk and a Hot Fuzz Location Walk:

There may have been some form of religious establishment on the site of the Cathedral before the first known church to be built close to the current site when around the year 705, Ine, the Saxon King of Wessex built a Minster.

The first documented reference to the Minister dates from 766 when the Minster was recorded as being near the “Great Spring of Wells”, highlighting that the wells have always been a focal point for having both the church and a settlement here.

Wells prospered due to its surrounding agricultural land, the wells, and the growing importance of the church, and in the year 909, Wells became the centre of a new Somerset diocese.

Wells has long had a religious relationship with Bath, and in 1088, King William Rufus granted the estates to Bishop John of Tours, who relocated to Bath, and the church at Wells ceased to be a Cathedral.

Wells was still an important church, and in 1175, construction of the new church commenced. Work on the church continued for the next few centuries, resulting in the magnificent building we see today.

Whilst the front of the church, seen in my father’s and my photos, is really impressive, in the Medieval period it would have been even more so, as it was brightly painted, and some small remaining traces of paint have been found in niches among the statues.

The interior of the Cathedral would also have been brightly painted, however over the years it was painted over, whitewashed, and any remaining traces of paint were lost in the 1840s when the building was vigorously cleaned.

Of the statues on the front of the church, three hundred of what were around 400 of the original medieval statues survive.

The interior of the Cathedral is magnificent, and at the end of the nave there is a scissor shaped structure:

The scissor arches were built between 1338 and 1348 to provide additional support to a high tower and spire that had been built above the Cathedral in 1313.

The weight of the tower caused large cracks to appear in the tower structure, and the scissor arches were the innovative solution to provide additional support.

Dating from around 1390, the Cathedral has what is believed to be the second oldest working clock in the world. The mechanism was replaced in the 19th century, however the dial is the original from the 14th century. The original mechanism is now on display in the Science Museum.

Above the clock face there is a turret, where every quarter hour, jousting knights appear and circle the turret. The same figure of the jousting knight has been knocked down for over 600 years.

To the right of the clock, and high up on the wall, is a figure, dressed in Stuart costume, that strikes the bell at every quarter:

Steps leading up to the Chapter House:

At the top of the stairs is the entrance to the Chapter House, which has a remarkable roof, consisting of thirty two ribs or tiercerons (which give the name of tierceron vault to the structure), which spring from the central pillar:

The Chapter House was completed in 1306, and provided a place for the governing body of the Cathedral (called the Chapter), to meet.

Above each of the seats around the edge of the room are brass plaques which name the “Prebend” which was the farm or estate from where the income came to fund the “Prebendaries” who were the priests who were part of the Chapter.

The Chapter House did have stained glass, however it is believed that these were smashed by Cromwell’s soldiers during the English Civil War.

Interior of the Chapter House:

Wells Cathedral organ:

Seating for the choir, with covered seats at the rear for Cathedral officials:

Wooden door within the Cathedral:

I could not find a date for the door, however the decoration is impressive. The decorative ironwork gives the impression of plants growing across the door:

Many of the floors within the Cathedral would have once been covered with colourful floor tiles, however today, only the following small patch of medieval floor tiles remain:

The Lady Chapel:

The Lady Chapel was ransacked during the English Civil War, when many of the Puritan soldiers thought that the decoration and stained glass of the Lady Chapel was still adhering to the Catholic faith.

In the Cathedral gardens:

There are a number of wells and springs surrounding the Cathedral, and in the following photo I am looking down into one of these in the Cathedral gardens. The sound of running water rises from the darkness of the entrance:

The Bishop’s Palace was the next place in Wells to find the location of one of my father’s photos.

This is the entrance to the Bishop’s Palace, across a moat that surrounds much of the palace:

This is my father’s photo from 1953 showing the moat, a couple of swans and part of the surrounding wall / gatehouse, in which there is an open window:

The open window is the point of interest, as zooming in on this, it is just possible to see a bell mounted on the wall, and a rope hanging down to just above the level of the water:

The bell is still there today, although in a slightly different position, and the rope had been taken inside the window.

There is a tradition with the swans at wells, which is believed to date back to the 1850s, when a Bishop’s daughter taught the swans to ring the bell for food.

The swans still ring the bell for food, however to stop them doing it at random times throughout the day, the rope hanging from the bell is tucked into the window, until the time for feeding.

Once through the gatehouse, we can see the Bishop’s Palace. The Chapel in the centre, and the walls of the ruined Great Hall on the right:

And what must be one of the most tourist friendly scenes – croquet on the lawn of the Bishop’s Palace, with Wells Cathedral in the background:

Inside the Chapel of the Bishop’s Palace. The Chapel was built between 1275 and 1292 for Bishop Burnell who was Lord Chancellor for Edward I. The Chapel has been used by the Bishop of Bath and Wells for many centuries.

Interior of the Bishop’s Palace:

In the gardens of the Bishop’s Palace, between the palace and the cathedral, we find the main evidence of the wells and springs that gave the city its name and led to the original religious establishment.

The wells and the streams running from the wells have been enclosed, with large gardens around the main wells. Originally, water would have risen from the ground here, and flowed away through a number of streams and marshy land.

There are five large springs that rise through the artificial pond seen in the photos above and below. Four of these springs rise through the sand and gravel at the bottom of the pond. The fifth source of water is at the far end of the pond in the above photo, and is water that is piped from wells beneath the lawns close to the cathedral.

In the photo below is the spring that was once called the Bottomless Well, due to the assumed depth of the well. It has been partly filled and lined with gravel, to prevent the flow of water from undercutting the stone walls of the pond.

The features where the water rises up through the ground at the bottom of the pond are known locally as “pots”, and after periods of heavy rain, the surface can be seen to bubble with the flow of the rising water.

The waters that rise through the ground in Wells originate across the southern side of the Mendip Hills, to the north and east of Wells.

A story of farmers in a hamlet to the east of Wells throwing waste chaff from their corn threshing, into a swallet hole, where a stream sinks into limestone, with the chaff reappearing at the springs in Wells was one of the first demonstrations of where the water was coming from, a distance of three miles.

Later tracing activities would identify eight or nine underground streams that were feeding the springs, with the time taken to travel underground dependent on the amount of rain that had fallen.

An experiment with one of the more remote swallets demonstrated that water would normally take 24 hours to reach Wells, however at times of drought it could take up to a week or more.

When dye has been used to trace the flow of water, the concentration of dye is the same at any of the springs in Wells, from any of the sources of water. This proves that the water from the remote swallets, where streams disappear below the surface, is carried to Wells along a single underground river, where it then rises to form a number of springs.

As the underground river rises in height, it breaks through the surface at different places to form the “pots” where it rises up from the limestone, through marl and finally through the gravel just below the surface.

The average daily output of the springs is about 4 million gallons. This can fluctuate between 40 million gallons after periods of high rainfall and flood, down to 1 million gallons during a drought.

Water is drawn of from the pond through an underground tunnel and a separate sluice, that both feed water into the moat around the Bishops Palace.

Some of the water from the springs is used to feed the streams running along the gutters of the High Street, as seen in one of the photos earlier in the post.

Whilst the springs and water from the springs rose in the land owned by the Bishop, in 1451, Bishop Beckington built a well house and laid lead pipes from the well house into the Market Place to provide water for the inhabitants of Wells.

The 15th century well house in the foreground of the following photo, surrounded by plants:

Part of the moat surrounding the Bishops Palace, with the cathedral in the background:

The above scene creates the impression of a smooth and calm flow of water, however there have been times when the level of rainfall has created some very dramatic conditions at Wells, such as this description of the springs from 1937, when “a torrent bursting up and even heaping sand above its level, making in gardens gaping holes out of which water gushes, at times leaping into the air, overflowing lawns and, with impetuous torrent, doing its best to sap ancient foundations”.

The closest part of the cathedral to the ponds and springs is the Lady Chapel, and there has been concern over the years that the amount of water in the springs after periods of high rainfall, could damage the buildings and undermine the structure.

Pipes take water from the springs closet to the cathedral away to the ponds, but at times in the past, water has been seen to erupt through the lawns.

On a sunny and warn late spring day, the gardens are glorious and the constant presence of water provides a connection with the geology below the ground and the water flowing in from the surrounding countryside.

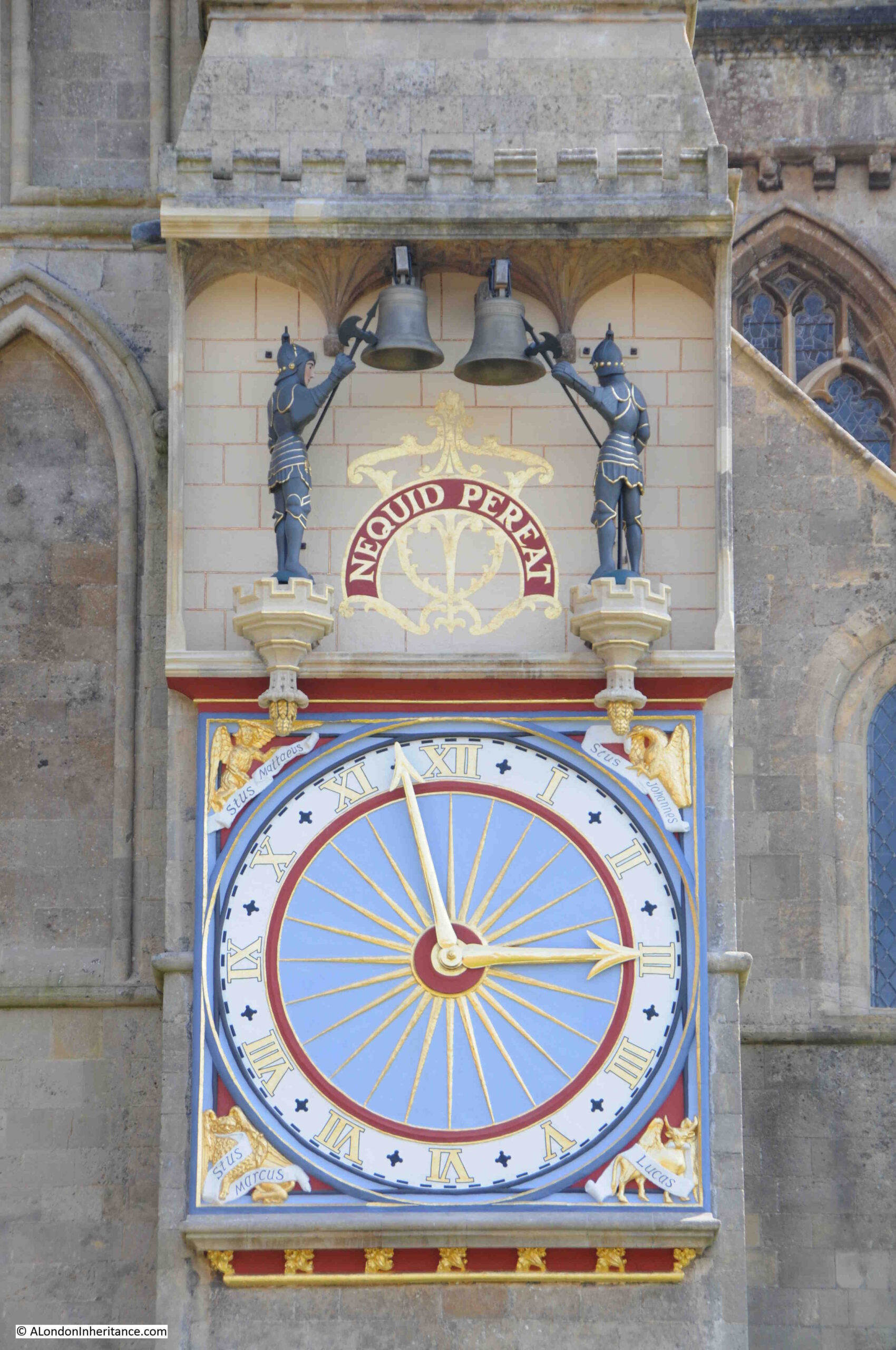

There was one last place that I wanted to visit, and to find it, we walked to the side of the Cathedral, where there is another clock:

The clock on the exterior of the Cathedral is driven by the same mechanism as drives the clock inside the Cathedral. This clock is believed to have been added around the 14th and 15th centuries, but has been restored a number of times since.

Not far from the clock is Vicars Close, dating from 1348, it is believed to be the oldest, mainly original, medieval residential street in Europe:

The houses were originally built to accommodate vicars, however since the 1660s, some of the houses have been leased out to other residents.

At the end of the street (see above photo), is a chapel. The Chapel, as well as a number of the houses are now used by Wells Cathedral School.

All the houses are Grade I listed.

View from the chapel end of the street, looking back to the Cathedral:

Wells is a really fascinating place to visit. I wish my father had taken more photos of the place in 1953, however the cost and limitations of film at the time, as well as how much could be carried on a bike probably limited the number.

What I like about Wells is it reminds us that towns were usually built at a location due to what was there at the time. Wells was built at this site because of the springs / wells that gave the place its name. Wells that are only there due to the unique geology of this part of Somerset.

You may also be interested in my visit to nearby Glastonbury, which can be found here.