Firstly, an apology. This post in nothing to do with London, however on the 75th anniversary of D-day, I wanted to write a post that brings together my interests in history, books and maps to commemorate such an important event, and the sacrifice of so many in what was one of the defining days of World War 2.

In 1946 the British Field-Marshal Montgomery published his personal account of the campaign to liberate Europe, from the landings at Normandy on D-day to the eventual defeat of Germany. The book is a detailed account of the operations, the battles, the logistics of the campaign to open and fight a second front from the west.

Reading the book, the logistics of D-day are staggering. The volume of men and equipment that had to be landed, the secrecy to ensure the landing sites were a surprise to the defenders, the bravery that ensured a bridgehead had been established by the end of D-day, and the challenges of then extending that bridgehead and fighting from Normandy to Germany.

Normandy to the Baltic consists of 222 pages of text, but what makes this book rather special are the two pockets to the front and rear of the book which contain a total of 47 coloured maps and 3 diagrams. The maps detail the campaign from D-day through to the closure of the war.

The front of the book’s dust wrapper – lovely bold colours and very evocative of the time.

The book was published when paper for publishing was still in short supply, and the book notes that “this book is produced in complete conformity with the authorised economy standards“.

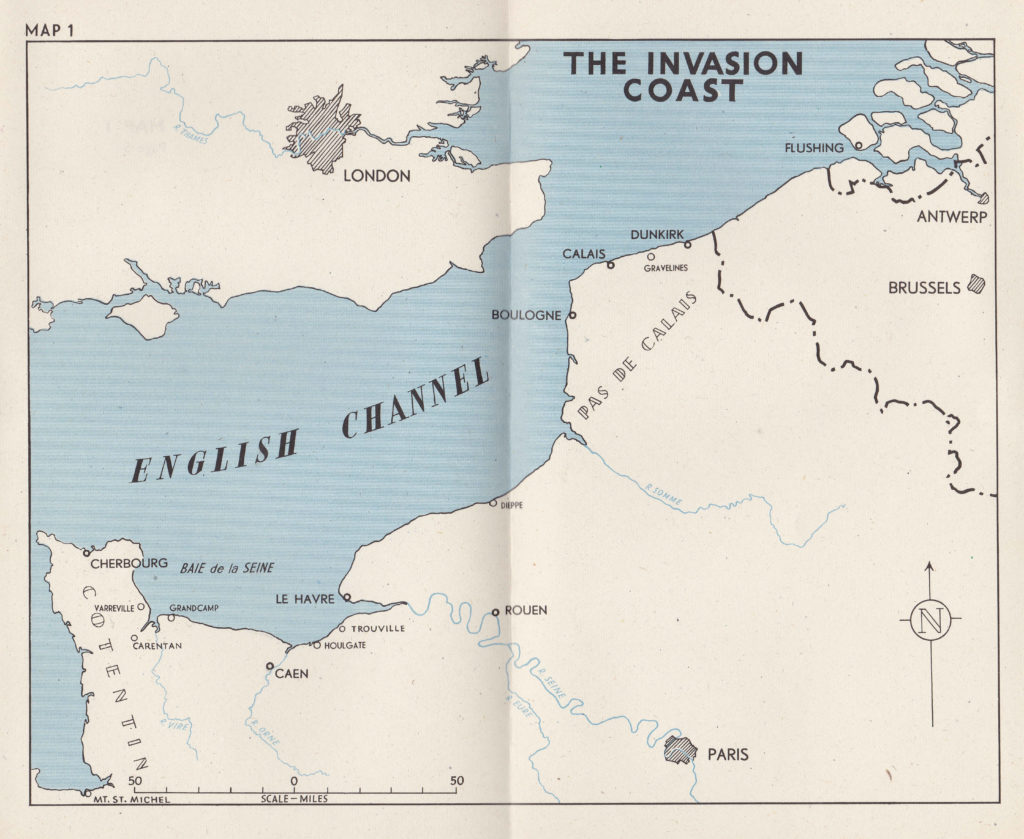

The first map highlights the invasion coast – the area from Dunkirk in the north to Cherbourg in the west that was considered as possible landing sites for the invasion. Dunkirk, Calais and Boulogne were the obvious locations as these were only a short distance across the channel and would therefore make the crossing easier, however this was a very heavily defended stretch of coast.

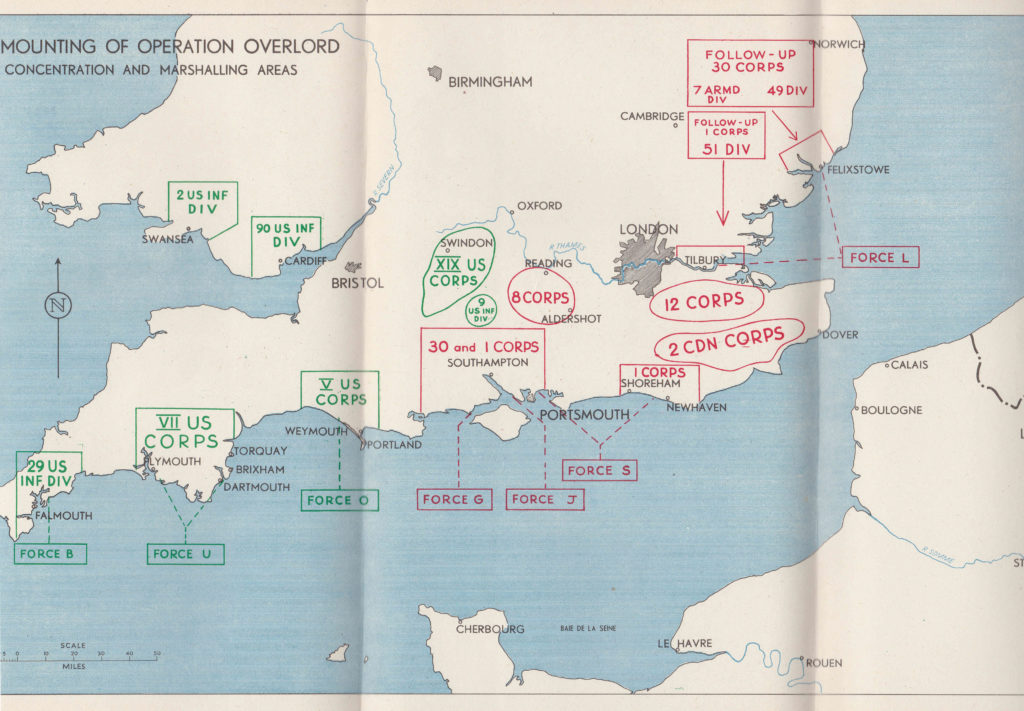

The logistics of managing such a large invasion force are remarkable. The army groups and all their equipment were marshaled across the south of the country, stretching from Wales through to East Anglia, and to the west of Cornwall. The following map shows the areas occupied by individual Corps and Divisions. They all had to be then transported to coastal embarkation points for transport across the channel on D-day and during the following weeks.

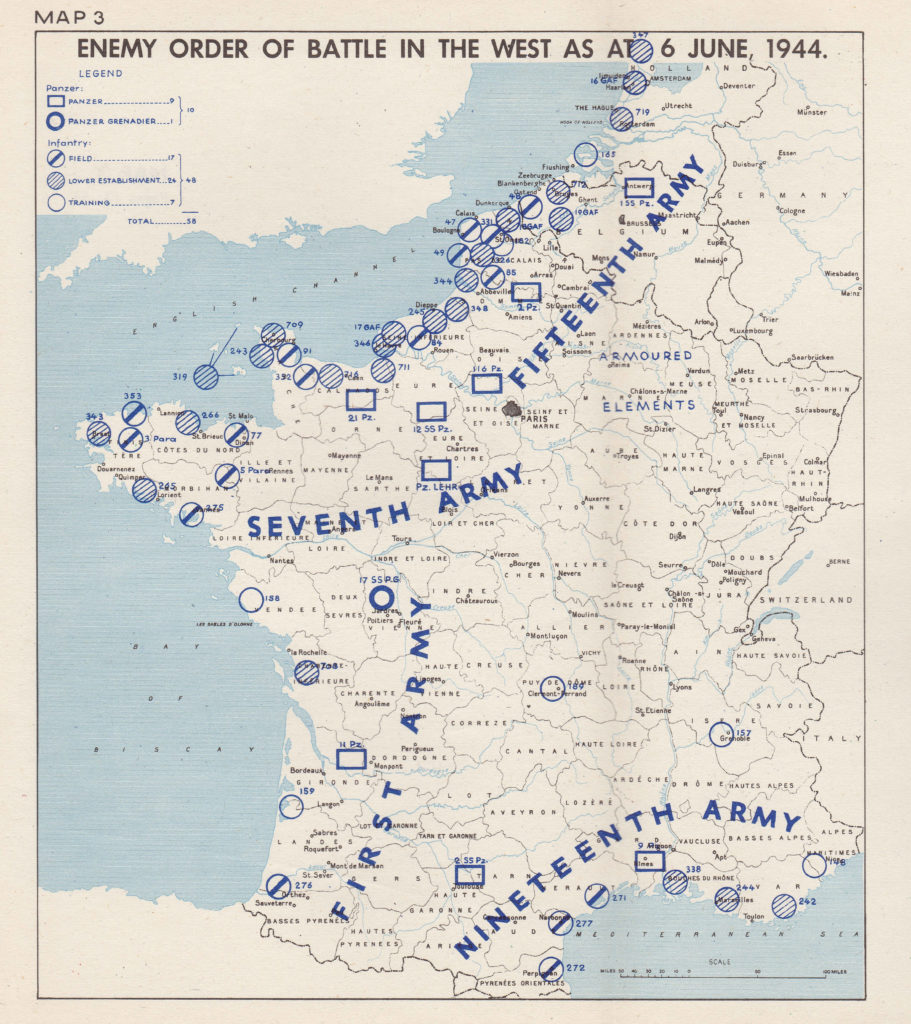

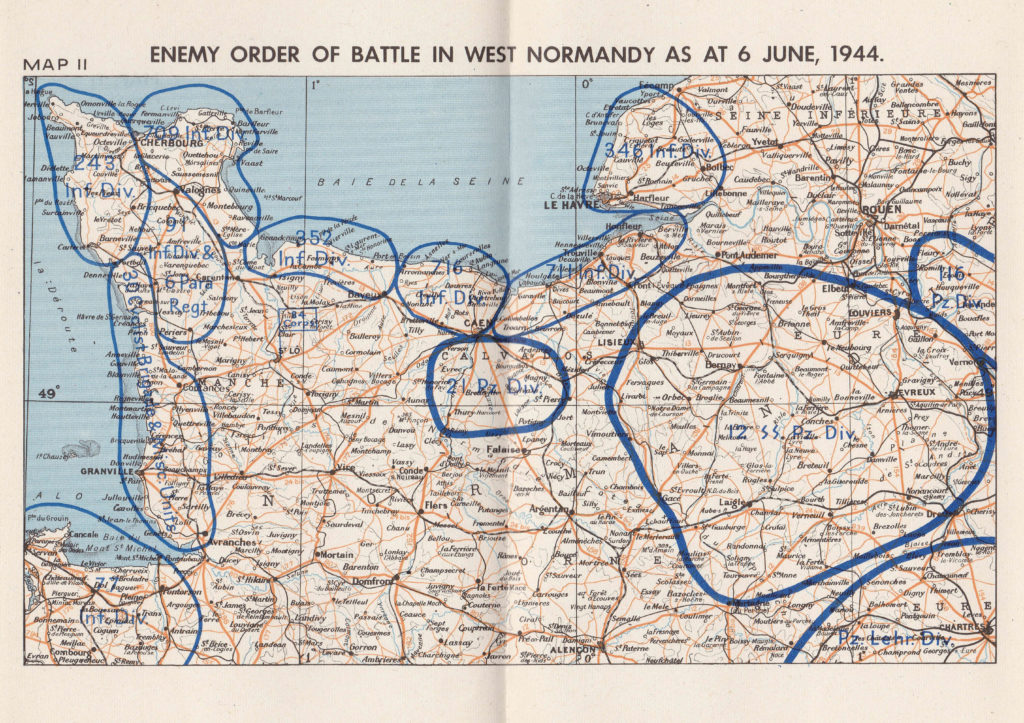

This map of German forces in France and Belgium shows the heavy concentration of forces along the French and Belgium coast where the distance across the channel was shortest.

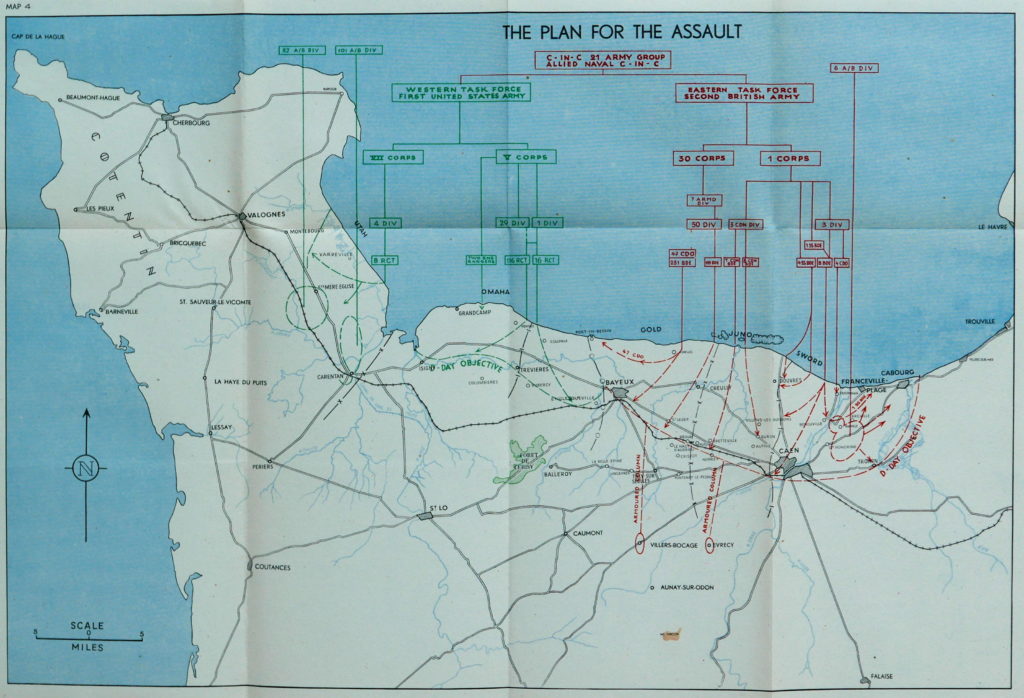

To avoid the heavy concentration of forces across the shortest stretch of channel, the plan for the assault was to land in Normandy, which would involve a lengthy sea crossing, but hopefully maintain an element of surprise and allow the Allied forces to establish a bridgehead before the defending forces could be reinforced.

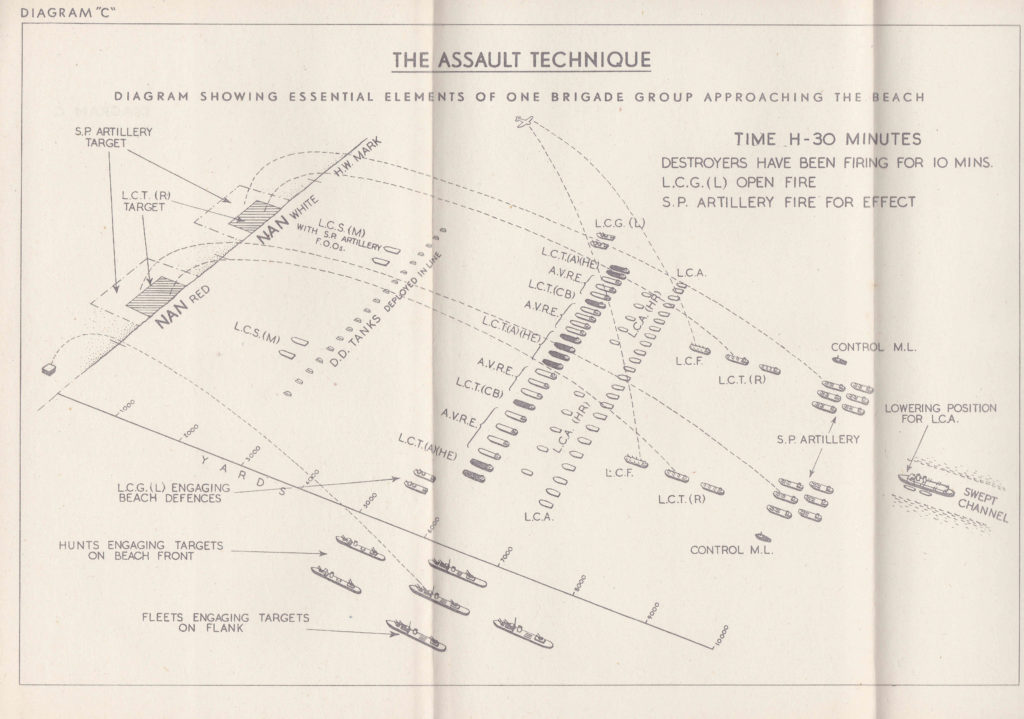

The organisation was incredible. The following diagram shows the assault technique and covers the various different types of specialised craft that had to be moved from the south coast of England to Normandy, arranged in the right order and to perform their role at the right time.

Although in reality, conditions such as the weather on the morning of D-day meant that the assault was not as precisely choreographed as the above diagram suggests. Landing craft often did not arrive at the right place, and in some instances, troops left landing craft when still in deep water, and many drowned as they were loaded with heavy equipment.

At the front were Landing Craft Support (LCS), craft that provided fire support to troops as they landed on the beaches. Behind them was a line of D.D. Tanks, or Duplex Drive amphibious tanks. These would be launched some distance from the shore and would make their way under their own power and flotation to the beach.

Behind then was a line of Landing Craft Tank (LCT), landing craft that carried tanks and other mechanised equipment for transport to the shore. Further back was a line of Landing Craft Assault (LCA), landing craft that carried the assault troops. As well at the LCTs, this line included Armoured Vehicle Royal Engineers (AVRE), landing craft carrying specialised equipment such as tanks fitted with flails to clear a path through mines, bridging equipment etc.

The assault was supported by Landing Craft Gun (LCG) artillery ships and destroyers tasked with bombarding the enemy positions before the landing, and providing supporting fire once the assault troops had landed.

Landing Craft Flak (LCF) were anti-aircraft variations of the landing craft, fitted out with anti-aircraft guns to defend against enemy aircraft.

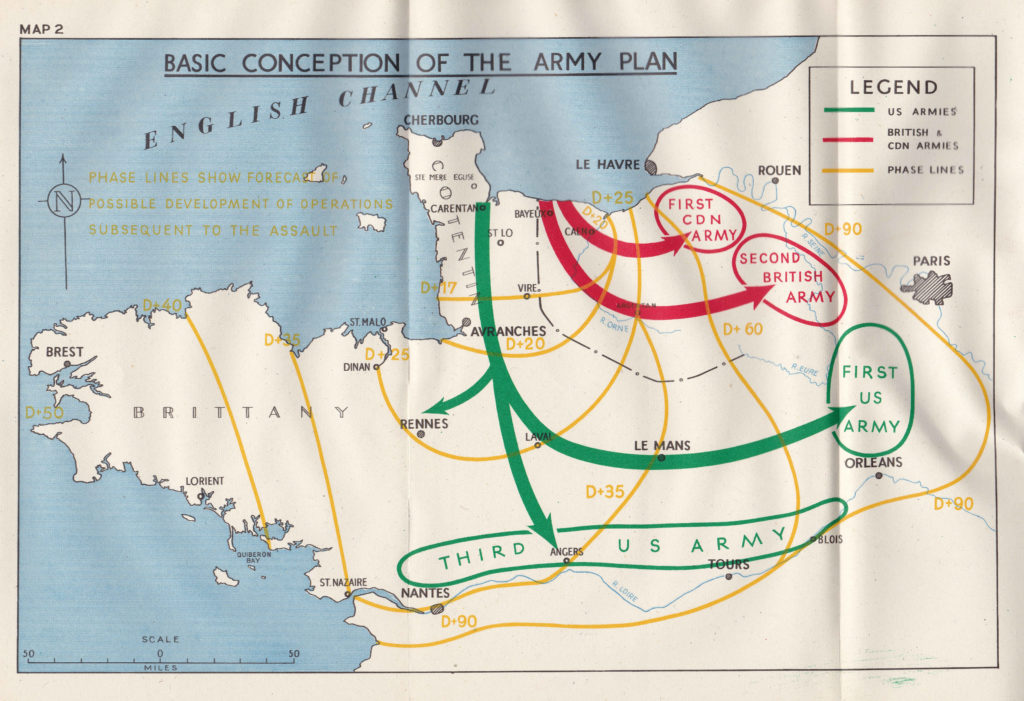

After landing and establishing a bridgehead, the plan was to quickly strike in land, with the US Third Army moving south and the US First Army, British Second Army and Canadian First Army moving east and north towards northern France, Belgium and Paris.

The distribution of German forces on the 6th June 1944, showing how every section of the coast was defended, with reinforcements inland.

Bombing on and after D-day aimed to frustrate the move of German reinforcements to the front by destroying railways, bridges and attacking columns of transport.

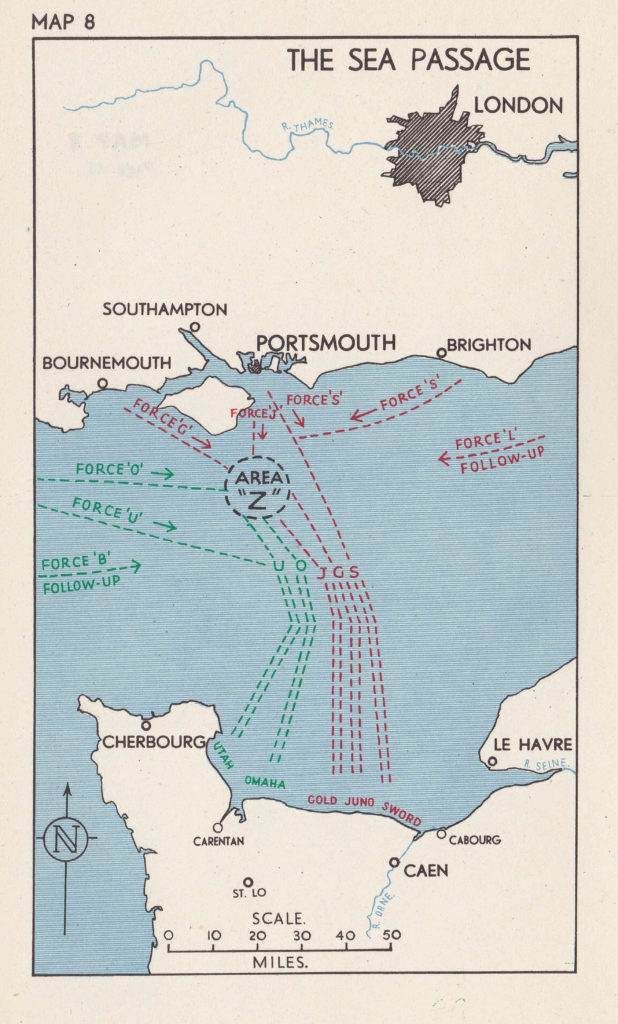

The following map again highlights the challenge of attacking Normandy. A lengthy sea crossing and the coordination of forces from across the south coast, including follow-up forces from Cornwall , the Thames estuary and Felixstowe.

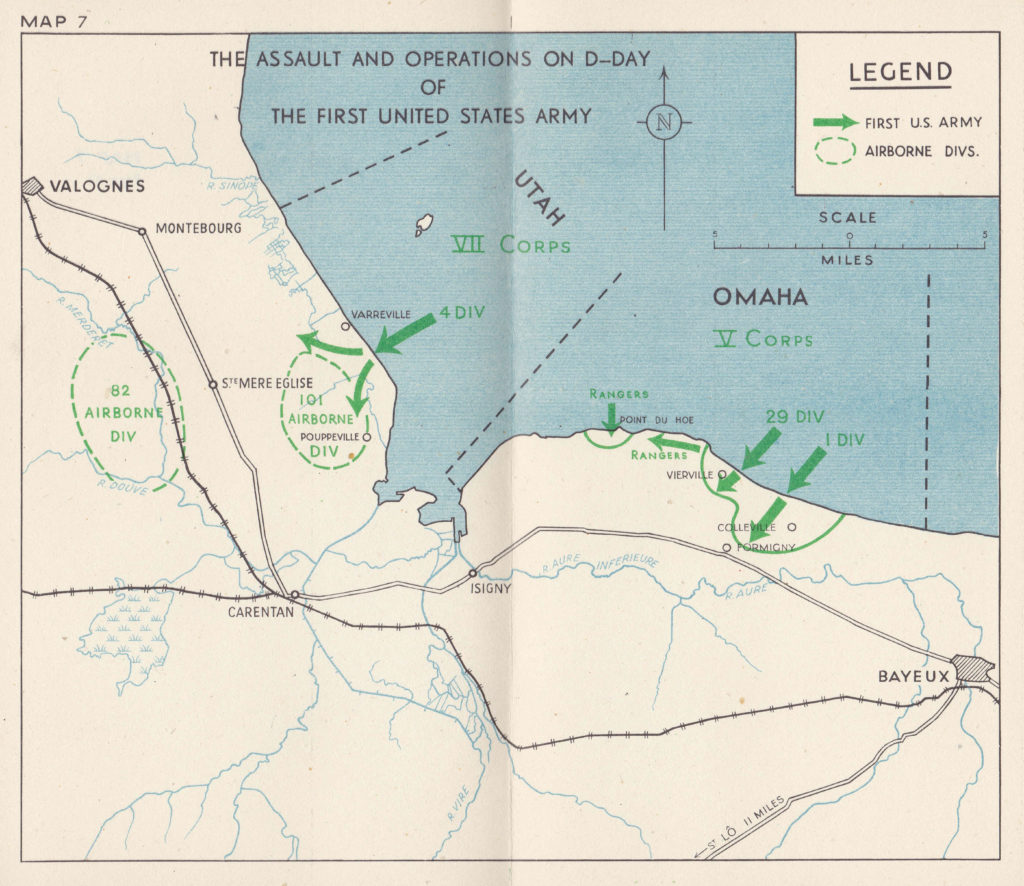

The US assault on the 6th June included airborne drops of parachute forces in the early hours. They suffered heavy casualties during the landing on the town of Sainte-Mère-Église as many buildings across the town had been set on fire which illuminated the descending paratroops.

By the end of the 6th June 1944, a bridgehead had been established and the push inland had started. 156,000 troops had landed on the first day, and an estimated 4,400 had died.

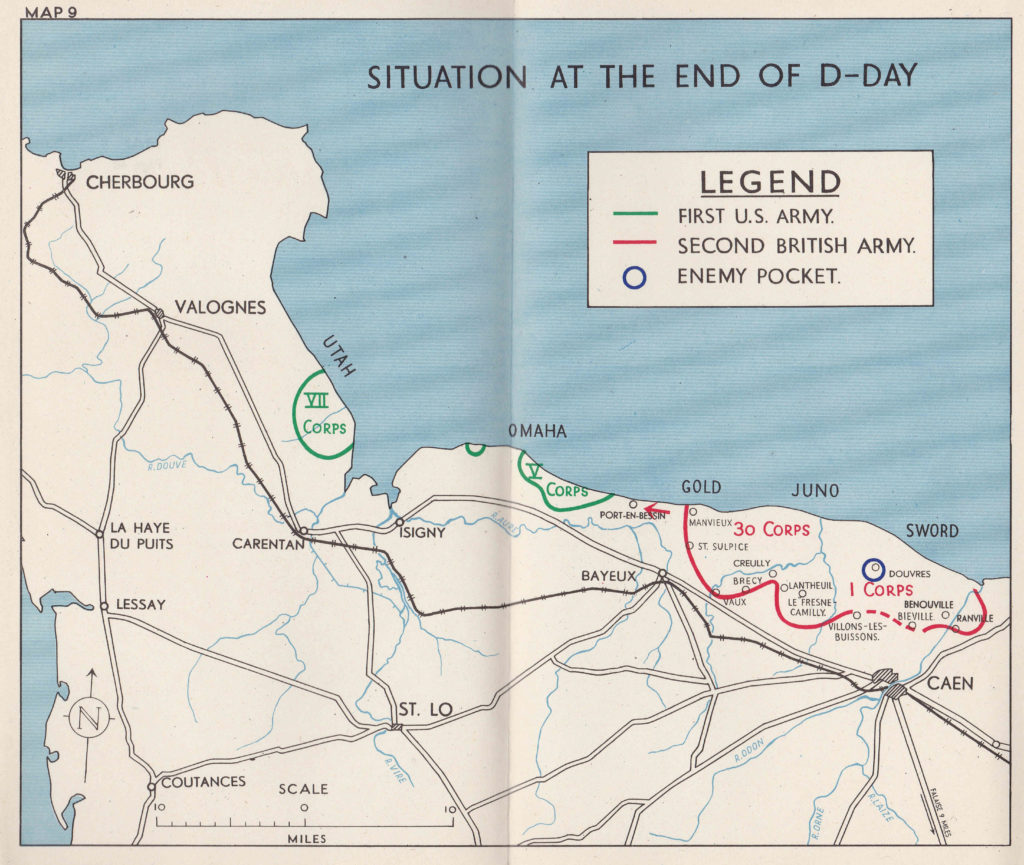

The following map shows the situation at the end of D-day.

In the book, Montgomery described the situation at the end of the 6th June as follows:

“As a result of our D-Day operations we had gained a foothold on the Continent of Europe.

We had achieved surprise, the troops had fought magnificently, and our losses had been much lower than had ever seemed possible. We had breached the Atlantic Wall along the whole Neptune frontage, and all assaulting divisions were ashore. In spite of the bad weather the sea passage across the Channel had been successfully accomplished, and following this the Allied Naval Forces had given valuable support by fire from warships and craft; the Allied Air Forces had laid the foundation of success by winning the air battle before the invasion was launched, and by applying their whole collective striking power, with magnificent results, to assist the landings.

In spite of the enemy’s intentions to defeat us on the beaches, we found no surprises awaiting us in Normandy. Our measures designed to overcome the defences proved successful. But not all the D-day objectives had been achieved and, in particular, the situation on Omaha beach was far from secure; in fact we had only hung on there as a result of the dogged fighting of the American infantry and its associated naval forces. Gaps remained between Second British Army and V United States Corps and also between V and VII United States Corps; in all the beachhead areas pockets of enemy resistance remained and a very considerable amount of mopping up remained to be done. In particular, a strong and dangerous enemy salient remained with its apex at Douvres.

It was early to appreciate the exact shape of the German reaction to our landings. The only armoured intervention on D-Day was by 21 Panzer Division astride the Orne, north of Caen. Air reconnaissance, however showed that columns of the 12 SS Division were moving west.

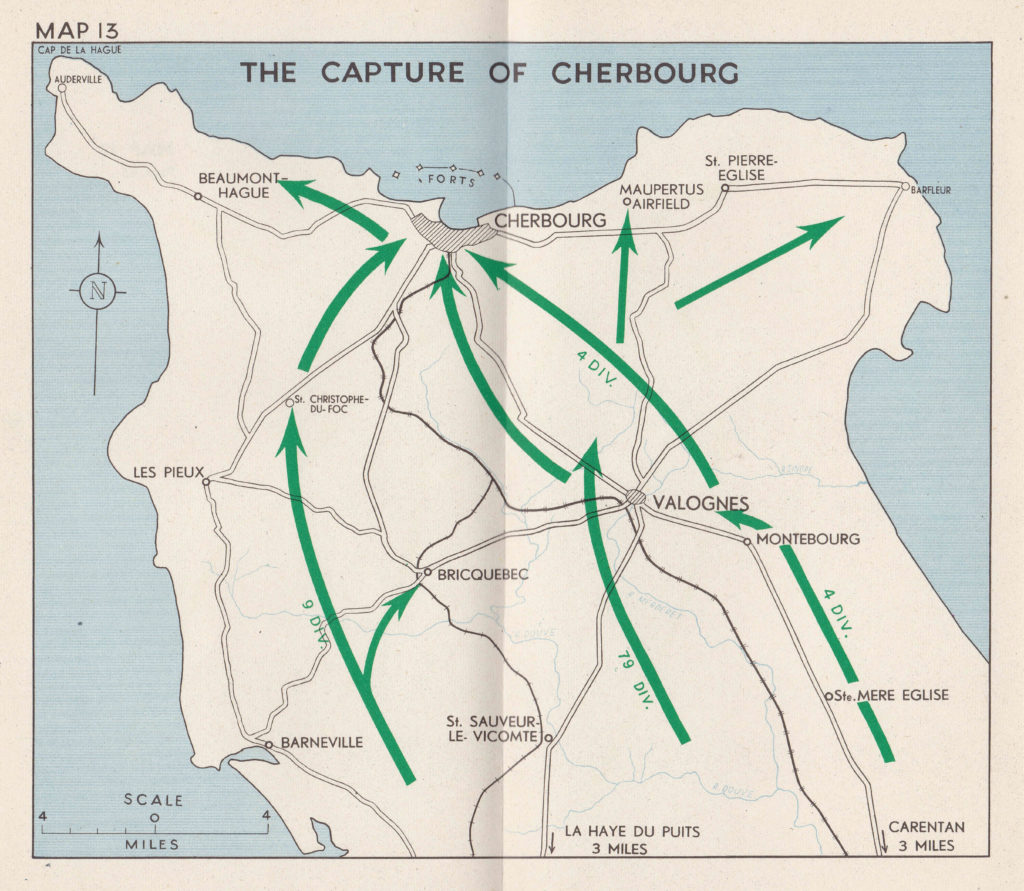

To sum up, the results of D-Day were extremely encouraging, although the weather remained a great anxiety. I ordered the armies to proceed with the plan; First United States Army was to complete the capture of its D-day objectives, secure Carentan and Isigny so as to link up its beachheads, and then thrust across the base of the peninsula to isolate Cherbourg as prelude to its reduction, Second British Army was to continue the battle for Caen, develop the bridgehead southwards across the Bayeux-Caen road and link up with the V United States Corps at Port-en-Bessin.”

Montgomery’s comments on the fighting at Omaha beach demonstrate how parts of the invasion were a close run thing.

That the bridgeheads had been achieved by the end of the 6th June was down to the considerable bravery of those involved in the assault, and the logistical achievement of transporting thousands of troops and tons equipment.

The 6th of June was just the start of a long campaign that would take British, American and Canadian armies all the way into Germany.

The breakout from the bridgehead would still take some weeks.

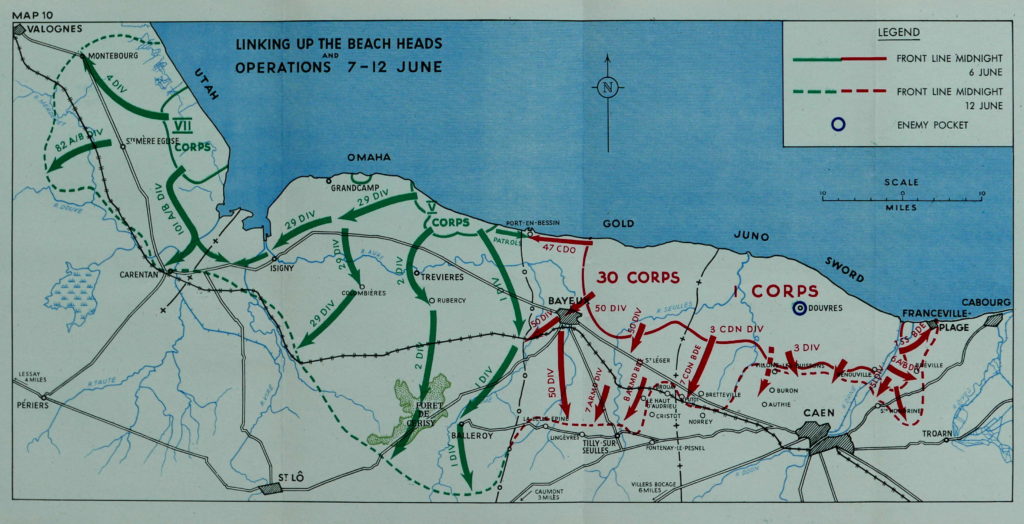

The following map shows the situation during the week following D-day with the start of the push inland from the beaches.

The advance after D-day was slow going. The nature of the countryside (wooded, hollow lanes, hedging lining the lanes) and growing enemy reinforcements meant that after establishing the landing, the push inland would be very challenging with considerably more killed and injured than during the initial landings.

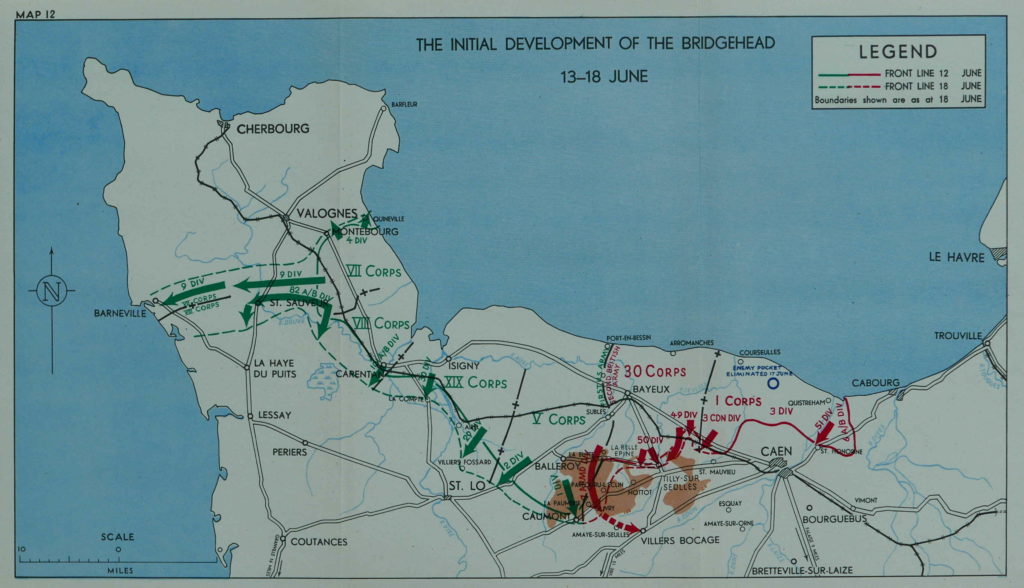

The initial development of the bridgehead during the second week after D-day:

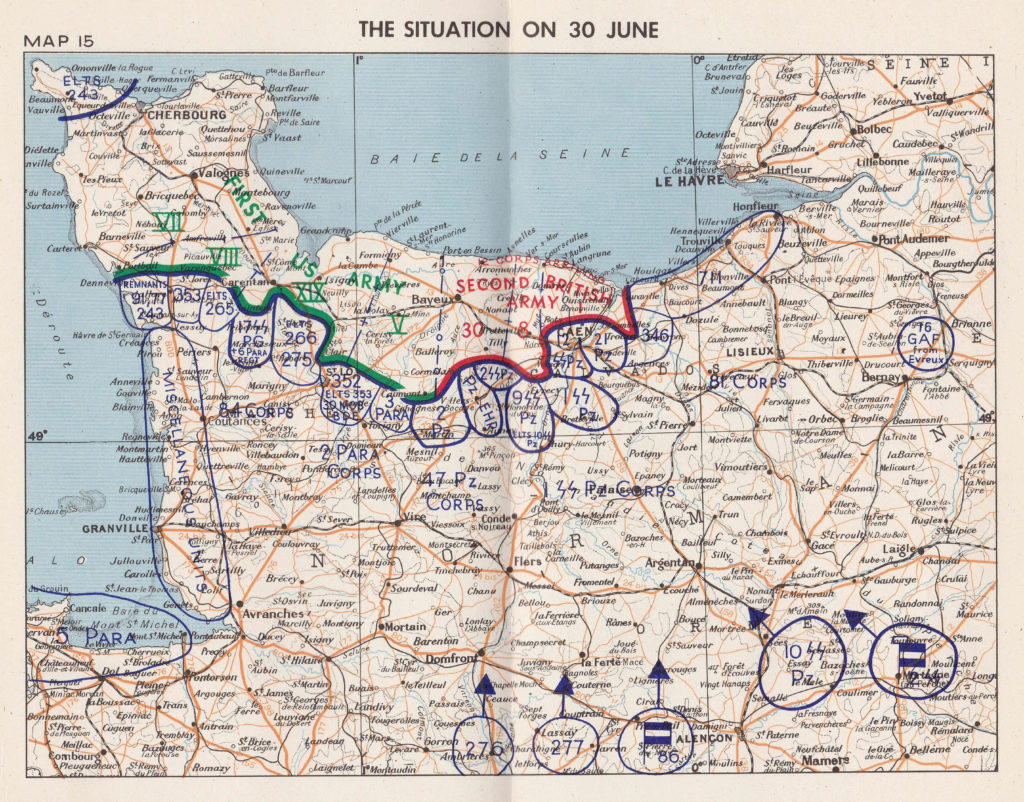

By the end of June, the Allied forces had made limited progress and were now up against an enemy force that was more coordinated than on D-day and with further arriving reinforcements. The following map shows the situation at the end of June, just over three weeks after D-day.

But progress was being made – the push up the peninsula by the American forces to capture Cherbourg:

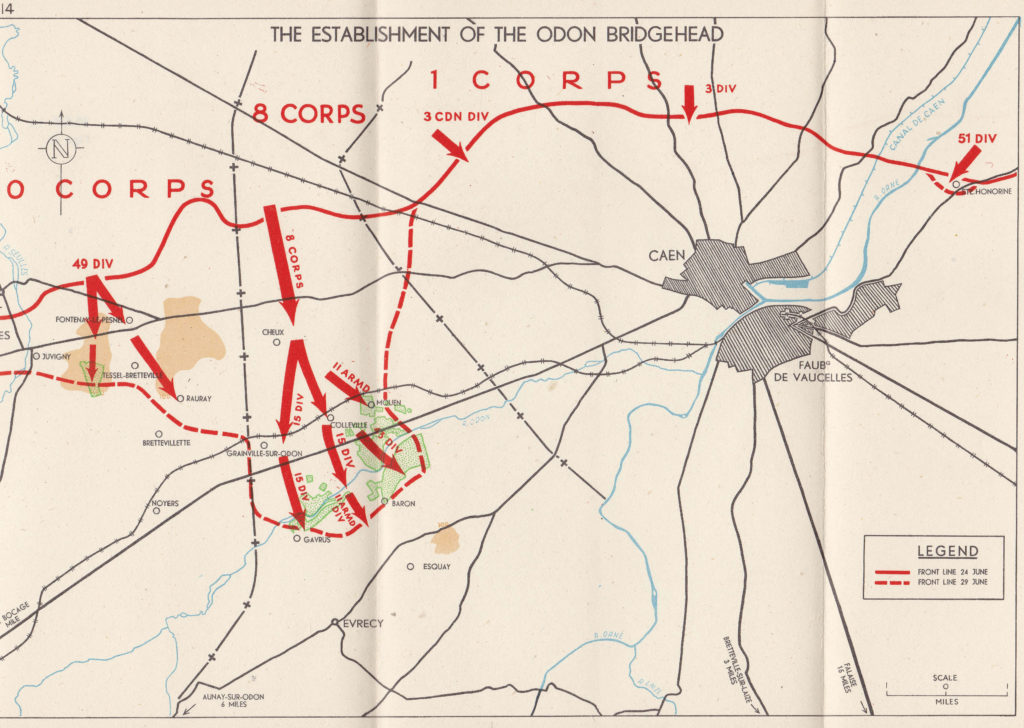

The British and Canadian forces start to push inland and to move towards the city of Caen:

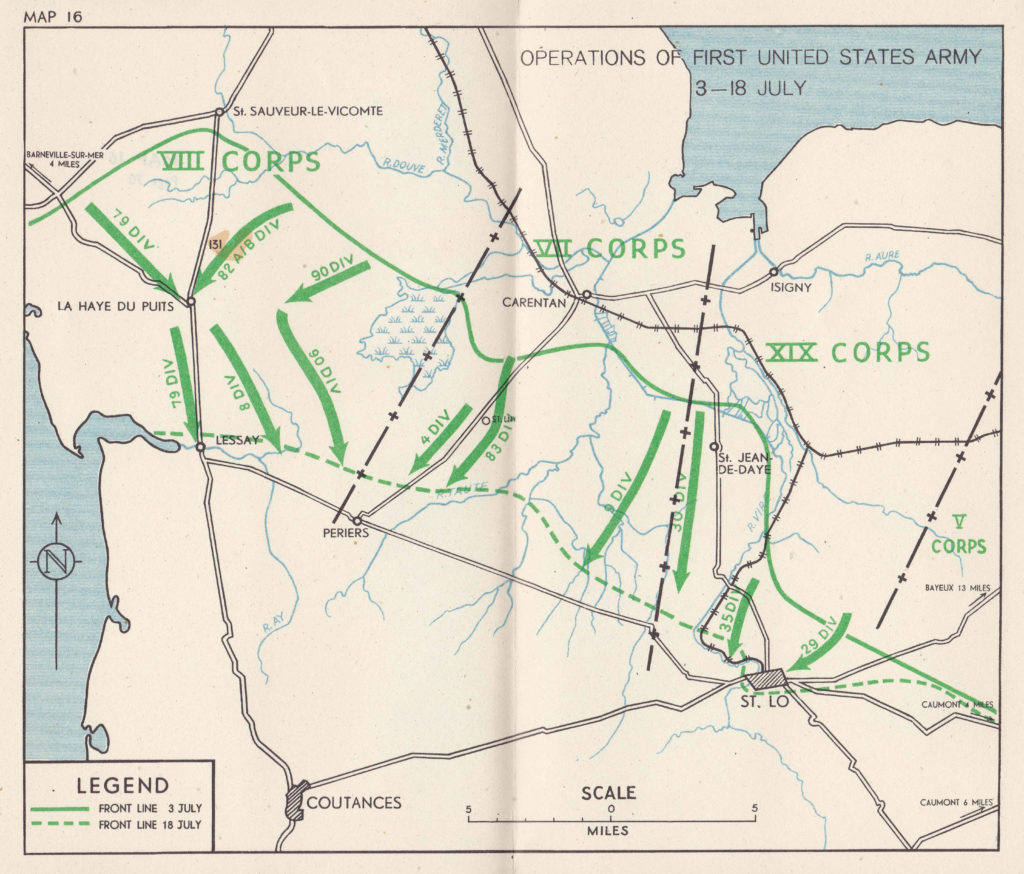

The US Army operations during the two weeks after D-day:

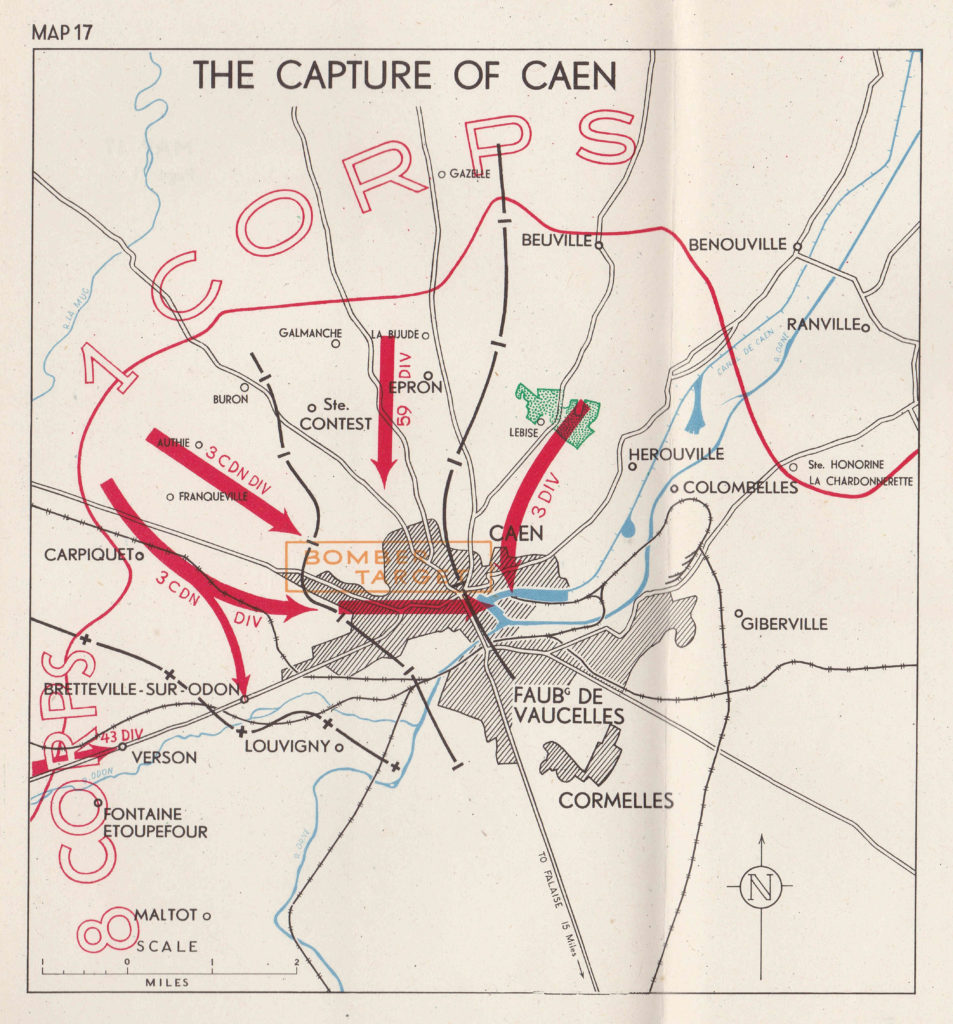

The capture of Caen:

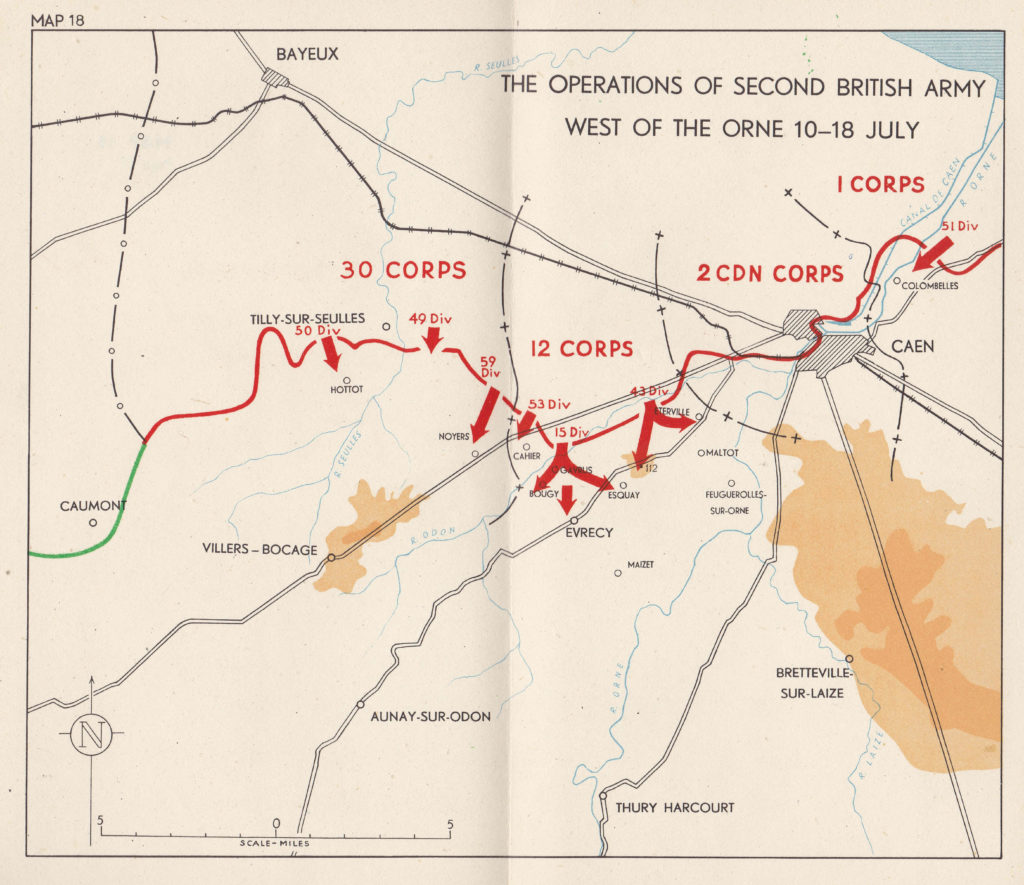

Operations of the Second British and Canadian Armies in July:

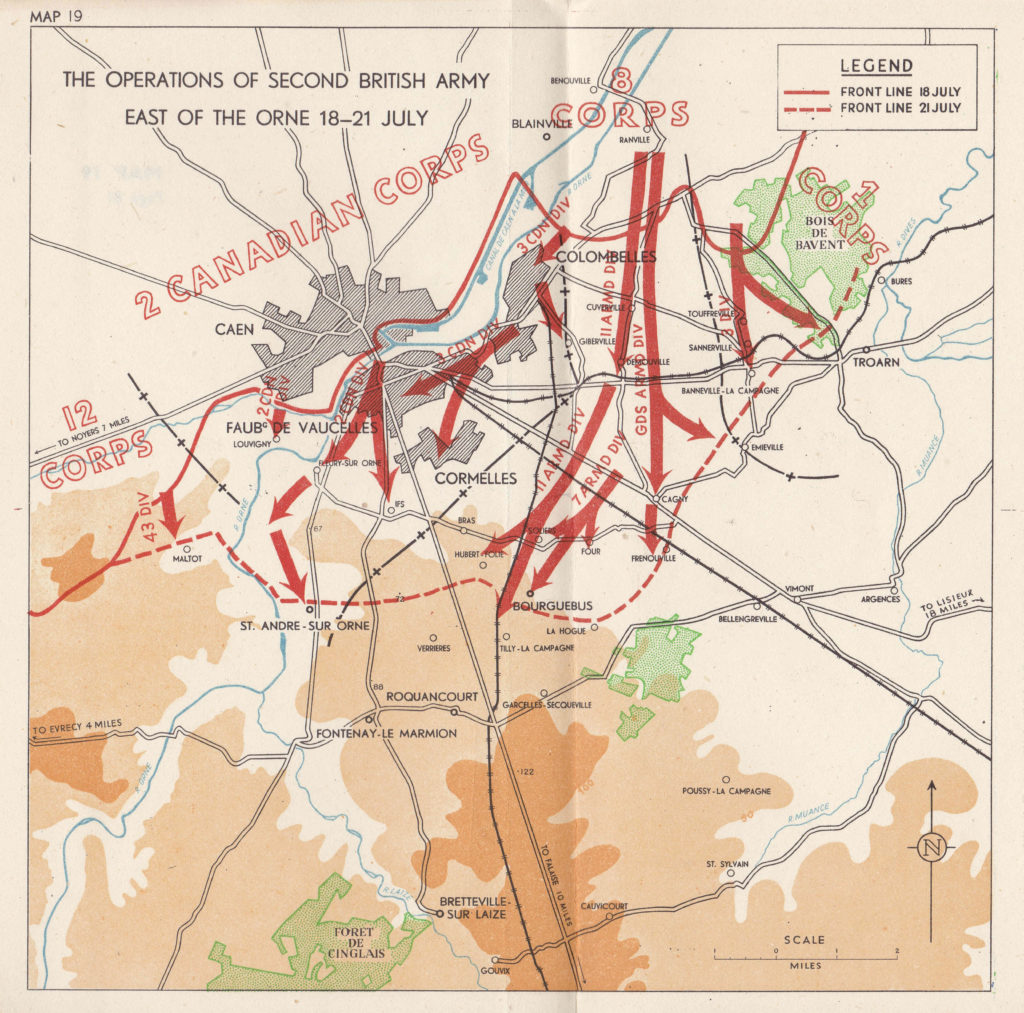

Moving south after the capture of Caen in the third week of July:

When the break out happened from the initial bridgehead, it was rapid and resulted in a breakdown in enemy resistance which resulted in the liberation of Paris when the German forces in the city surrendered on the 25th August 1944.

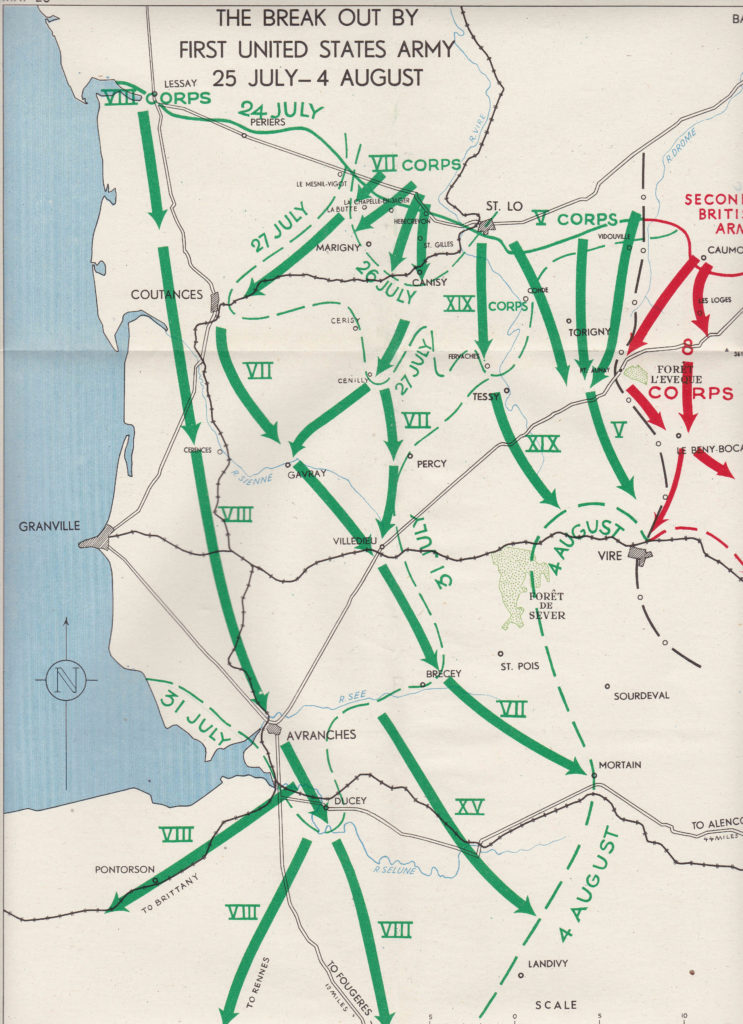

The following map shows the break out by the First United States Army between the 25th July and 4th August.

After the August breakout, progress would then be relatively rapid, however the overstretched supply lines and regrouping of German forces would cause delays and set backs, for example with the failure of Operation Market Garden in September 1944 to reach Arnhem, cross the Rhine and turn into Germany.

Montgomery’s book is a fascinating account of the campaign, which started on the 6th June 1944, and would end on VE Day, the 8th May 1945. The rest of the maps in the book follow the course of the campaign between these two dates.

That D-day was a success was down to a phenomenal achievement in logistics and planning, long before the days of instant communications, computers and spreadsheets, allied with the incredible bravery and sacrifice of those who took part.