Continuing my journey through the Netherlands of 1952, I have now reached Rotterdam.

The bombing of Rotterdam in May 1940 provided a warning of what would fall on London later the same year.

The invasion of the Netherlands started on the 10th of May 1940 with advance drops of parachute forces on key locations such as the Hague and the major city and port of Rotterdam.

The Dutch army within Rotterdam defended the city more aggressively than expected and by the 13th May the invading forces had made very limited progress.

On the 14th May 1940, the city of Rotterdam was heavily bombed. Indiscriminate bombing by 90 Heinkel bombers caused significant damage to the city which was made even worse by the fires that followed the initial attack. A strong wind caused the fires to extend to areas of the city that had not been directly bombed.

The attack killed between 800 and 900 people, over 25,000 houses were destroyed and 638 acres of the city left devastated.

Soon after the 14th May raid, Rotterdam capitulated, and the majority of the Netherlands surrendered on the 15th May with the whole of the Netherlands being occupied on the 17th May. The threat of similar levels of devastation on other Dutch cities was the primary reason for the rapid capitulation.

Occupation until the end of the war in 1945 prevented any significant reconstruction. After the end of the war, reconstruction commenced with a focus on the dock facilities which were back operating as one of the most efficient global ports by 1950.

When my father arrived in Rotterdam from Tilbury in 1952, much of the city centre was still in ruins, and some of his photos are similar to the photos he had taken of the worst hit areas of London.

He also found one of the great modernist designs of the Dutch architect, Willem Marinus Dudok, which although severely damaged in the 1940 raid was not finally demolished until 1960. The people of Rotterdam would also suffer badly during the occupation, and reminders of these events could (and indeed still are) be found across the city.

I had hoped to visit the city during the time we were in the Netherlands, but ran out of time due to other visits, so there are no before and after photos in this post. We had been many times when we lived in the Netherlands, but as I had not scanned these negatives, I was not aware of these 1952 photos.

In the case of Rotterdam, before and after photos would also be somewhat irrelevant as the city is so very different. Post war, and ongoing construction has resulted in a city centre that, with a few exceptions, is so very different to the city prior to the 14th May 1940.

So if you had taken the Batavier II from Tilbury to Rotterdam in 1952, stepped ashore and headed to the city centre, this is what you would have found:

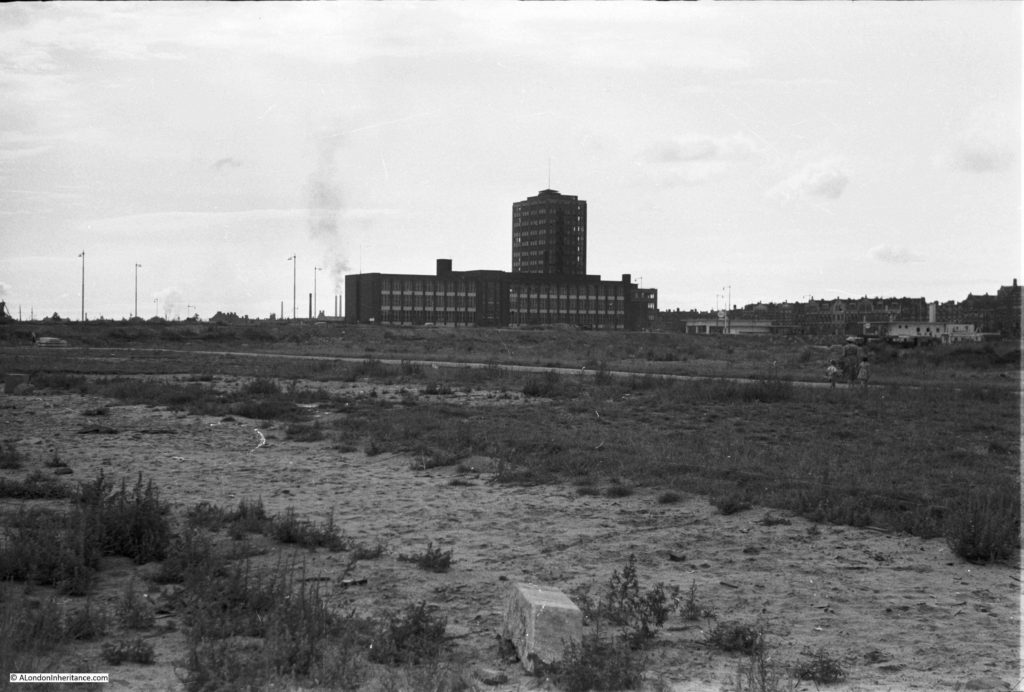

Although these photos were taken 12 years after the invasion of the Netherlands and 7 years after the end of the war, much of the city centre was still empty.

The level of destruction was such that the decision was taken to clear the city centre rather than rebuild the ruins that remained. This resulted in a clearer demarcation between the buildings to remain and the area for rebuilding than could be seen in London.

An initial plan for the reconstruction of Rotterdam included retaining much of the original street plan, however a later plan approved in 1946 called for a more significant change, moving the city away from a complex, narrow street plan to larger and more open streets, open spaces and large building plots. The devastation to such a large area of the central city had also resulted in the focus of the city moving away from the original centre and this change was also incorporated in the new development plan.

Some of the new construction under way:

The following photo shows the Laurenskerk church which was very badly damaged, but in the early stages of reconstruction in 1952.

The above photo includes an indication of how much the city has changed. On the right hand edge of the photo can be seen a railway viaduct. During reconstruction, the opportunity was taken to replace the above ground viaduct with an underground tunnel. As well as removing what could be considered an eyesore in the centre of the city, it also made available more space and removed the dividing effect that a large viaduct can have on different communities within a city.

A similar approach for London was included in the 1943, London County Council, County of London Plan, and also in the 1946 report to the Minister of War Transport, where many of the above ground railways through the city were proposed to move to underground tunnels. The money and will to carry out these proposals were not readily available so London’s railway routes are much as they were pre-war.

More rebuilding:

To the right of the above photo can be seen part of the building shown in the following photo, A large building but I have not been able to trace the building which may have been a survivor from before the war.

My father’s photos show just how large an area had been devastated by the initial bombing and the fires that would follow:

One building that whilst badly damaged, was not demolished was the De Bijenkorf department store building:

My father took several photos of this wonderful building from different angles so it must have been of significant interest to him.

De Bijenkorf was (and still is) a Dutch department store company and after building new stores in the Hague and Amsterdam, issued a tender in 1928 for the design of a new department store in Rotterdam.

The design by the Dutch architect Willem Marinus Dudok was selected.

Dudok was the city architect for the city of Hilversum, but was also responsible for a wide range of designs across the Netherlands.

His design for the Rotterdam department store was revolutionary. It created the largest department store in Europe when the Rotterdam De Bijenkorf opened on the 16th October 1930.

The design used significant amounts of glass to maximise natural lighting with a central atrium which also let in light to the centre of the building.

On one corner of the building was a tall minaret, topped by a diamond shaped lantern.

At night, the diamond lantern acted as a beacon across the city, and the whole department store was brilliantly lit with the glass windows showing off the illuminated interior and ground floor shop windows.

The shape of the building was similar to an ocean going liner, suddenly moored in the centre of Rotterdam, bringing together goods from around the world for purchase by those wealthy enough to shop in the store.

The rear of the building was significantly damaged during the May 1940 bombing. Over half of the building had to be demolished with the rest of the building patched up as best as possible, given the wartime conditions.

The store had only lasted 10 years.

The following photo shows the rear of the building in 1952. It had originally extended much further back.

The following postcard provides a view of the size of the De Bijenkorf department store soon after completion.

The photo shows the long glass windows running along the length of the side wall. There is a restaurant on the terrace at the top of the front of the building. The minaret and lantern were the tallest structure in the area surrounding the store. The photo also shows the original street plan and density of building. As can be seen in my father’s photos, all these buildings will be destroyed in the bombing, subsequent fires and demolition.

Part of a rear view of the department store. It would have originally extended all the way back to where my father took this photo.

After the war, the remaining part of the original De Bijenkorf store was too small. Technology had also changed, so interior lighting could be provided without large amounts of external glass which was expensive to maintain and keep clean. Post war department stores needed to have large areas of flexible internal space. Side walls could be solid, with bright internal electric lighting and only ground floor shop windows needed glass to show off their displays of goods to be purchased in the store.

A new store was commissioned, this time by an American architect, and Dudok’s building was demolished in 1960.

One of my father’s photos showing one of the new, much wider streets close to the De Bijenkorf store.

The website of Frans Blok has recreations of what Dudok’s building would look like in the Rotterdam of today, as well as a fascinating video showing Rotterdam in the 1920s, the construction of the building and the interior of the De Bijenkorf store.

As a view of what was to come with the redevelopment of Rotterdam, the HBU tower block in the following photo is one of the early high rise buildings of Rotterdam’s post war development. The building still survives.

More post was development, very different to the pre-war city:

New shopping developments:

Another view of the post war HBU building:

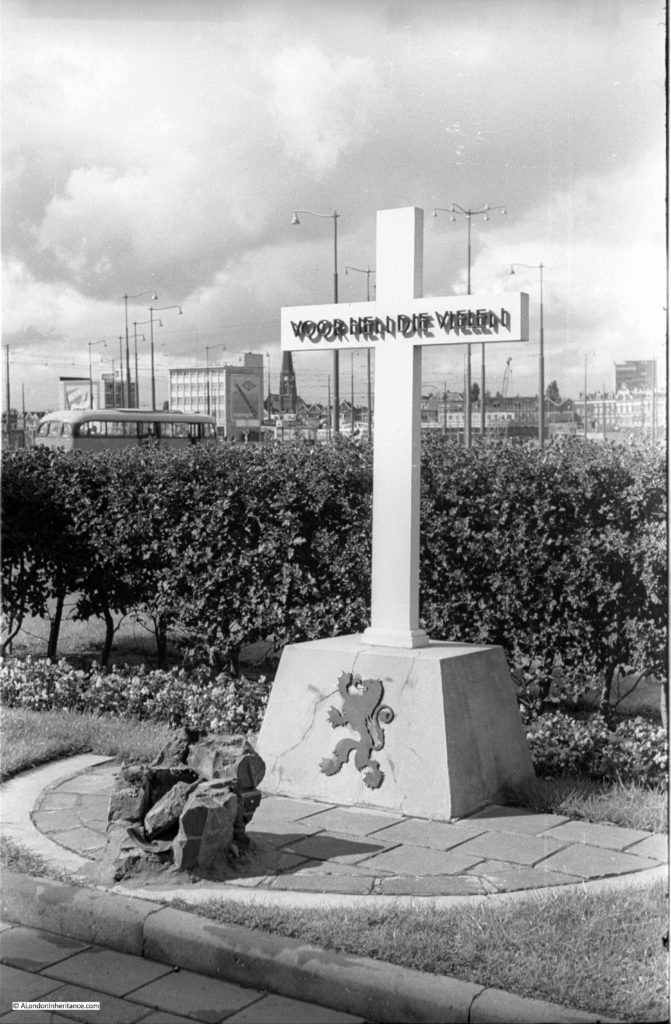

The Dutch population suffered terribly during the occupation. Not just the day to day loss of freedom, but random selection for execution was also a risk to the population.

When trying to escape arrest, you would run the risk of being shot. After an attack by the Dutch Resistance the occupying forces would randomly select groups of people for execution – always a larger number than had been killed in the resistance attack. A revenge for the resistance activity as well as an attempt to deter such attacks.

After the war, memorials were erected at the places where shootings and executions had taken place. They carried the words “Voor hen die vielen” – “For those who fell”.

These memorials are at the places where executions of between 10 and 40 randomly selected men were executed in reprisal for resistance attacks.

These memorials can still be found across the city and are a strong reminder of the brutality inflicted at random on the civilian population during the years of occupation.

The following photo is on the Rotterdam negative strips, however I have no idea where it was taken, or what the photo represents. What appears to be a submarine – I assume it is real rather than some form of reproduction.

Perhaps not what you would expect to find in a large city such as Rotterdam, however in 1952 my father took the following photo of a windmill that had survived the 1940 bombing.

The windmill dated from 1711 and having survived the war was destroyed in a fire in 1954. It was not reconstructed, and the area (the Oostplein) is now a large open road junction with a small grassed area in the centre.

My final photo from 1952 is the following, which I also included in last Sunday’s post on Amsterdam. The photo was on the same negative strip as some of the Amsterdam photos, however I could not find the location, but assumed it to be in Amsterdam.

I am very grateful to Henk Laloli who commented on the post that “The last picture with the escalator is probably in Rotterdam: the entry for cyclists and pedestrians to the Maas (river) tunnel. A lovely old wooden escalator and beautiful 1930s decorations.”

So hopefully I now have the right city for this photo of the tunnel entrance with the wonderful decoration.

Rotterdam today continues to be Europe’s largest port and the city plays host to many Dutch and international businesses, occupying the glass and steel towers that continue to grow across the city. The function of Rotterdam is the same as the pre-war city, but the architecture now is very different.

For my next post on the Netherlands, I am heading to the city of Nijmegen, to start exploring the impact of Operation Market Garden.