You may be wondering why a blog about London is featuring a post on Glastonbury. Long time readers will be aware that as well as London, my father also took many photos around the country, starting with a post National Service series of bike rides with friends. Starting from London, these journeys crossed much of the country, and one stop was in Glastonbury, to climb, and take some photographs of, Glastonbury Tor.

And as with the London photos, I am trying to work my way around the locations of these photos, although it is a much slower process. The above photo is of Glastonbury Tor and was taken on the 16th of August 1953, as are all the black & white photos in this post.

We visited Glastonbury on a sunny autumn day in 2022, and this was the first glimpse of Glastonbury Tor from a distance:

Walking through the town of Glastonbury towards the Tor:

The walk from the centre of Glastonbury took us along Chilkwell Street to Wellhouse Lane (wells are a feature of the legends of Glastonbury), where the south-western footpath to the top of the Tor starts. The Tor is managed by the National Trust who have created a path up the Tor to direct walkers and prevent erosion on the surrounding land.

The path continues to the very top of the Tor, with steps or a flat path, depending on how steep the ascent.

I thought it would be easy to recognise where I needed to take the “now” photos to compare with my father’s, however in many ways, the appearance of the Tor’s landscape is very different. In 1953 there was no path to the top of the Tor. It appears to have been grassland, grazed by cows, and I suspect there were very few walkers to the top of the Tor compared with today.

The above photo is my very rough comparison photo to the photo below. Very different cameras and lens used for the two photos result in a different perspective, however the shape of the ground can be compared. The construction of the path may have included flattening of the land around the path to create a smoother ascent.

At the top of the Tor is the tower of St Michael’s Church, the only part that remains of a church and monastic buildings that were on the top of the Tor. The tower dates from the 14th century, but with many later modifications and repairs.

The above photo is a 2022 comparison with the following 1953 photo:

In the above 1953 photo, the top of the Tor has a much more natural appearance. No footpath, although the grass leading up to the tower does look flattened. Cows are on the grass, and the tower is surrounded by railings, preventing access. This may have been down to the condition of the tower in 1953. Today the tower is open and you can walk through.

Glastonbury Tor is a remarkable geological feature. Rising around 520 feet above the surrounding landscape, the Tor dominates the area.

The low lying surrounding landscape, the Somerset Levels, is composed of layers of marl (a mixture of clay and lime), limestone and clays. Midford Sandstone forms the highest ground in the area, including that of the Tor. The surrounding landscape was originally much higher, however erosion over very many thousands of years has reduced the land to the height we see today.

The Tor is believed to have resisted much of this erosion due to a higher level of iron content in the sandstone, which produced a harder material, better able to resist erosion from wind and water.

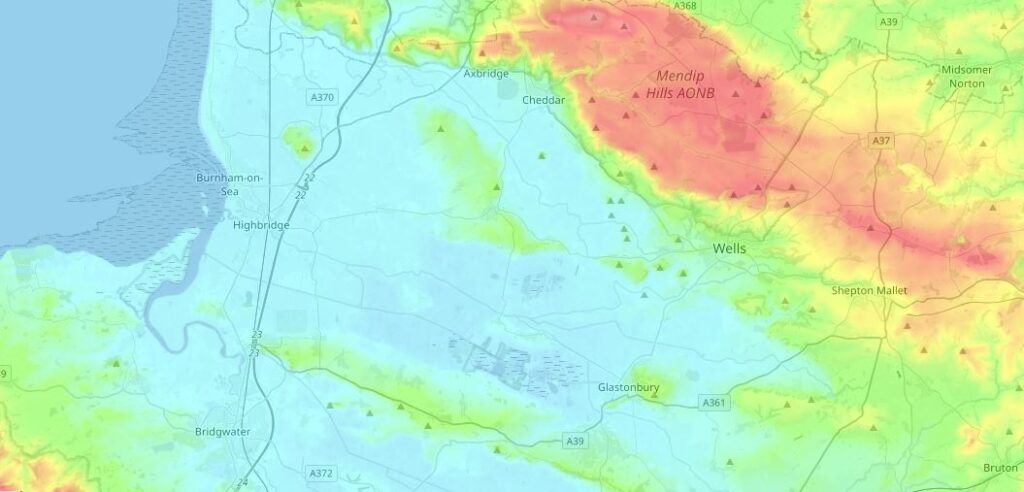

The following map (from the excellent topographic-map.com) shows land height as different colours, with blue as the lowest height, up through green, orange, red and pink as the highest. The Tor can be seen in red in the centre of the map, showing Glastonbury as an island in much lower land:

Taking a much wider view of the area, Glastonbury is the area of green to the lower right of centre of the map. The Bristol Channel is the dark blue to the left of the map, and the lighter blue between Glastonbury and the Bristol Channel shows that parts of Glastonbury and the Tor were once an island in an area of low lying water and marsh, before much of this was drained.

The dark red feature to the north are the Mendip Hills, and to lower left, the red in the corner indicates the Quantock Hills. The whole of the light blue area in the above map once suffered frequent floods from the sea, and much was very marshy land, which has now mainly been drained leaving high quality agricultural land.

The views from the top of the Tor are superb. In the following photo the cathedral city of Wells, roughly five miles north of the Tor can be seen, with the cathedral standing out to the right. The tall feature in the background is a radio and TV transmitting mast on the higher land of the Mendips.

Wonderful views surround the Tor in all directions:

Looking south:

A circular plaque provides directions and distances to features in the distance:

The town of Glastonbury at the base of the Tor:

Compared to the quiet scenes in my father’s photos, on our visit there was a steady stream of walkers to the top of the Tor.

The history of the Tor is complex. There have been some Roman tiles found on the Tor, but no firm evidence of any occupation. There may have been a fortified structure on the top of the Tor around the year 500, and it is between the years 450 and 540 that the legends of King Arthur associate him with Glastonbury. whether he was a real person or an idea of the continuation of Romano-British culture after the Romans have left.

There appears to have been a small monastic settlement on the top of the Tor around the tenth century. Excavations on the Tor have found the top of a Celtic cross. The style of the cross is similar to others from around the 10th and early 11th centuries, and the standing cross may have been a feature at the top of the Tor.

The monastic community appears to have grown in size, and during the 12th and 13th centuries, a substantial community was established at the top of the Tor with a church occupying the highest point.

The original church was destroyed by an earthquake in 1275. Despite the substantial appearance of the church today, there are many fissures in the limestone below which somewhat weakens the foundations of buildings on the Tor. Excavations have found that previous builders have attempted to use old building material to plug these fissures.

The church was rebuilt at the end of the 13th century, and the present tower was added around the year 1360.

The niches on the tower for statues were added in the 15th century. Most of these have disappeared, however on the right is a statue of St Dunstan, and on the left is the lower part of a statue of St Michael.

There are a couple of reliefs on the tower, above the entrance arch. The relief on the left is that of an angel watching over the weighing of a soul, the relief on the right shows St Brigit milking a cow.

The following photo is looking through the entrance to the church within the tower. The view at the far end of the tower would have been into the nave of the church:

Walking through the tower and a look up reveals that the tower is open to the elements:

The church on the Tor was taken by the Crown during the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII in 1539.

The Tor played a gruesome part in the dissolution. Richard Whiting, who was aged around 80 was the Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey, which was the last remaining of the Somerset monasteries during the dissolution.

On the 19th of September 1539, the royal commissioners arrived at Glastonbury without warning with the intention of finding treasure held by the Abbey and evidence against the Abbot for concealment of treasure.

The royal commissioners ransacked the Abbey and the Abbot’s rooms and papers. They spent time searching for treasure and eventually found a significant amount which was taken by the Crown.

Richard Whiting was taken to the Tower of London for interrogation, then sent back to Wells where a show trial took place and he, along with two others from the Abbey community, were found guilty.

On the of 15th November 1539, Richard Whiting, along with two of the Abbey’s monks, John Thorne, the Abbey Treasurer and Roger James, the Sacrist who had also both been found guilty, were taken on a hurdle through the streets of Glastonbury and dragged to the top of the Tor, where they suffered the barbaric execution of being hanged, disemboweled, beheaded and quartered.

Whiting’s head was stuck on a spike in front of the now closed Abbey.

Following the dissolution, the church on the Tor fell into gradual decay. Stones being removed for other building work, and left to the wind and rain blowing across the Somerset Levels.

The tower did survive, but has needed repair both to the structure and foundations due to ongoing erosion. By 1985, the foundations of the tower had been exposed by several feet, and hardcore and concrete was used to build up the area around the foundations.

The following photo from the Britain from Above website is dated 1946 and shows the railings around the church as in my father’s photo:

In the above photo, terraces can be seen running around the Tor. The origin and purpose of these terraces has never been fully explained. They could be due to natural dropping of the land, or possibly man-made terraces or strip-lynchets, which were created to support medieval agriculture by providing terraces of reasonably horizontal land on which to grow crops.

This may have been of importance to a growing monastic community, when much of the surrounding Somerset Levels were still marshy and had not be drained sufficiently to support farming.

There are also myths that the terraces were some sort of processional route to the top of the Tor, however there is no firm evidence to support this, and it is just one of the many myths associated with Glastonbury.

The top of the Tor is frequently the scene of numbers of people at solstice events, for example welcoming the longest day of the year, and the Tor features in many theories about earth powers and magic, for example with the Ley Line theory popularised by Alfred Watkins in his 1924 book “The Old Straight Track” where he wrote about his theories of prehistoric lines in the landscape that marked out long routes across the land, marked by key features such as standing stones, churches and landscape features.

One long Ley Line bisects the tower on the Tor and is named the St. Michael’s ley-line after the number of features along the route with a connection to St Michael.

There is no scientific prove regarding Ley Lines, and whilst Watkins saw them more a marking out of routes for travel, from the 1960s onwards they have taken on a more spiritual meaning as a route of earth powers.

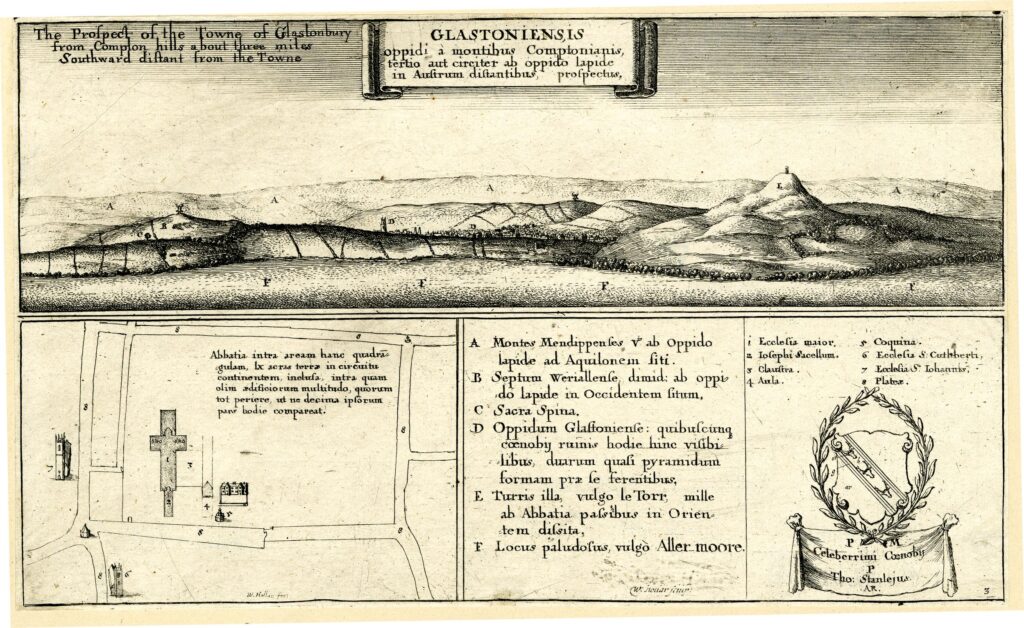

The tower at the top of the Tor adds to this sense of difference to the Tor and to Glastonbury, and has long been a feature worth recording, for example it is seen in the following print of the view towards Glastonbury dating from 1655 (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

Water adds to the sense that Glastonbury is a special place. Wells and springs have long featured around the base of the Tor, and the most well know Well is Chalice Well, which can be found a short distance from the Tor.

Chalice Well is spring that comes from deep underground and flows at a remarkably consistent rate of 25,000 gallons per day at a temperature of 11 degrees Centigrade. The well is also known by the name of Blood Well due to the red tinge to the water from its high iron content.

Myths around the well go back to some of the founding myths of Glastonbury when Joseph of Arimathea came to Glastonbury, perhaps with the chalice used at the last supper, or with vials of Christ’s blood, which some stories tell were put into the well.

Walking along Chilkwell Street (believed to be from Chalice Well Street), there are other flows of natural water running into drains:

Although my father had not photographed the site of the Abbey, a visit was essential to understand more about the history and myth of Glastonbury.

The founding story about Glastonbury is that it was followers of Christ who had settled in Glastonbury and built the first church on the site in the first century AD.

A variation of these stories is that Joseph of Arimathea. who was entrusted with the Holy Grail, was passing through the land that would become Glastonbury. he set his staff on the ground whilst he slept, and the staff took root and burst into life and became the tree known as the Glastonbury Thorn.

There is obviously no way to know whether there is even a hint of fact behind these stories, and most of them seem to originate in the medieval period.

There does though appear to have been some form of monastic establishment at Glastonbury in the 7th century, and in that period it must have seemed a special place with the Tor rising high above the surrounding water and marsh covered land. The high ground of the Tor and around Glastonbury rising above the water is also why the name Isle of Avalon has also been used for the area around the Tor.

By the 10th century, Glastonbury was sufficiently important to have been the burial site of two Saxon kings, Edmund 1st and Edgar.

After 1066 , the Abbey came under Norman influence, but it was not until the 12th century, and Abbot Henry of Blois that Glastonbury Abbey became one of the major monastic sites in the country.

I mentioned the dissolution of the Abbey and the fate of the last Abbott, Richard Whiting earlier in the post. After the takeover of the Abbey by the Crown, it was given to the Duke of Somerset.

Stone was removed from the Abbey buildings and used in the construction of other buildings, hardcore for roads around Glastonbury, etc. and the buildings of the Abbey began a long decline into ruin.

The Abbey was originally a very substantial collection of buildings, and the remaining ruins provide a glimpse of the impressive size of the Abbey before the dissolution:

The doorway in the following photo is the north entrance to the 12th century Lady Chapel. The Lady Chapel stands on the site of an earlier timber church that is claimed to have been founded by Joseph of Arimathea.

There are bands of carvings around the doorway, with the outer most band displaying animals and figures in combat. the inner bands show biblical scenes from the Life of the Virgin Mary, which include St Bridget milking a cow (as can also be seen on the tower on the Tor).

View from inside the Lady Chapel looking along the full length of the old Abbey. The upper parts of the view date from mainly the 12th and 13th centuries. Below ground level is the late 15th century St Joseph’s Crypt.

View towards the walls that once stood either side, and supported, the main tower of the Abbey:

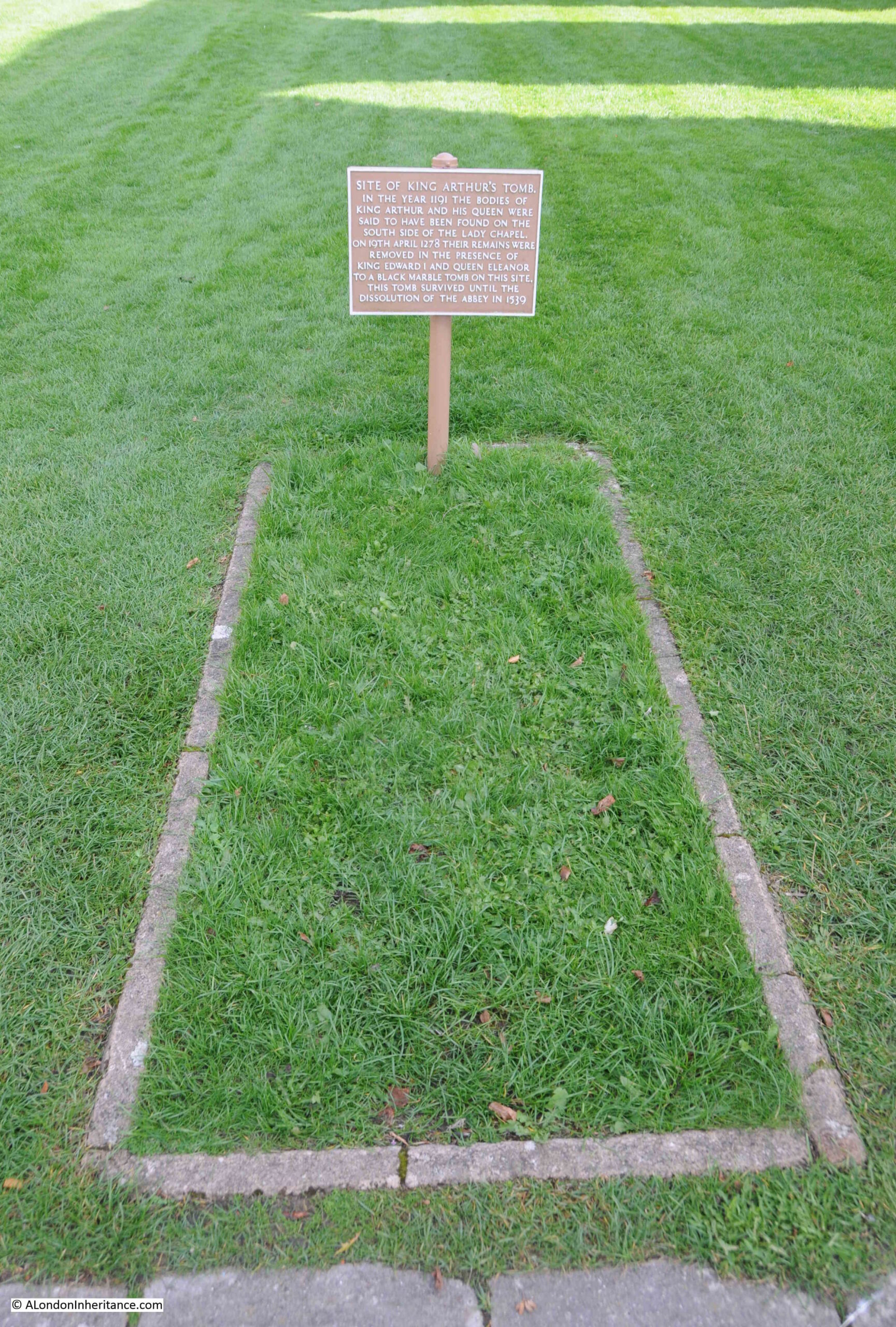

Just inside the two walls in the above photo is the relic of another of Glastonbury’s myths.

In 1184 much of the earlier Abbey was destroyed in a fire. King Henry II supported the rebuild of the Abbey, with the Lady Chapel and much of the church being completed by his death. The rest of the Abbey complex still needed to be rebuilt and royal funding dried up after Henry II’s death, and then the monks of the Abbey miraculously found the bodies of King Arthur and his queen, Guinevere.

Such a find raised the profile and importance of the Abbey, funds became available to complete the rebuild and by the end of the 13th century works were complete and the bodies of Arthur and Guinevere were reburied in a ceremony attended by King Edward I and Queen Eleanor.

Although the black marble tomb and bones were lost in the dissolution and subsequent ruin of the Abbey, the site where the bodies were reburied is marked today:

Whether the bodies were really those of Arthur and Guinevere is impossible to confirm, and it has always raised suspicion that the bodies were found just at the time that the Abbey was in urgent need of funds to complete rebuilding works.

Having the tombs of King Arthur and Guinevere in your Abbey does wonders for the institution’s prestige.

The site where the bodies were found is also marked by a smaller plaque which states that it stands at the “site of the ancient graveyard where in 1191 the monks dug to find the tombs of Arthur and Guinevere”.

King Arthur and Guinevere’s black marble tomb was just in front of the high altar, which is marked out on the grass today. It must have been a really impressive sight.

Impressive side walls to the nave of the abbey:

I found a rather strange London connection at Glastonbury Abbey, in the Abbot’s Kitchen, one of the best surviving example of a monastery kitchen:

The view inside the kitchen, which has been set-up to show what a medieval monastery kitchen may have looked like:

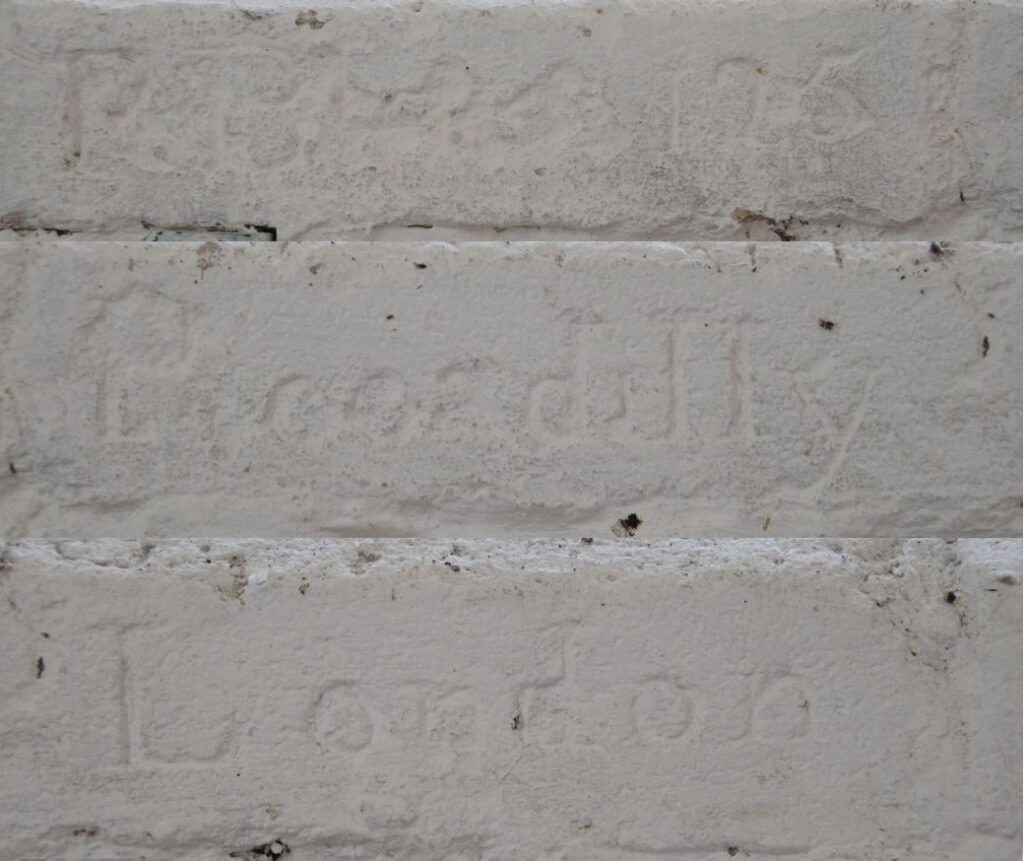

There is a large window to the left of the above photo. At the base of the window a sloping wall runs down to the vertical wall, and along this there are a series of stones which have graffiti across them.

Rather than show the stones in a line as the detail is not that clear at a distance, I photographed each stone and stacked them above each other in the following image, where the top stone was on the left and bottom stone on the right:

The top stone appears to have an incomplete date, possibly from the 18th century. The next two stones have a much clearer inscription of Piccadilly London.

I have no idea why there should be an inscription of Piccadilly London in the Abbots Kitchen in Glastonbury. Whether this was a tourist, or some other connection, it is very strange.

Leaving Glastonbury Abbey, the High Street probably has one of the more unusual range of shops for an English town. Shops selling crystals and stones, bookshops covering every form of mysticism and early religion, standing stones and stone circles, witchcraft and paganism. Shops with names such as the Goddess and Green Man sit opposite an estate agent.

At one end of the High Street there is a Market Cross. A Grade II listed 1846 cross that replaced an earlier 16th century cross that had fallen into disrepair:

The oldest building in the High Street is that of the Glastonbury Tribunal, a 15th century stone town house with an early Tudor façade. The building now houses the Glastonbury Lake Village Museum, which was closed on our visit, only being open at weekends:

Glastonbury is a remarkable town, it is the sort of place where you come away believing some of the myths and legends surrounding the place. Standing at the top of the Tor, imagining how it must have seemed centuries ago, with the Tor standing tall above the surrounding low lying Somerset Levels, covered in water it is easy to see how myths attached to the place.

The Tor is also a magical place to photograph, and for the best photographs of, and from the Tor, can I recommend the work of Michelle Cowbourne, who frequently posts incredible photos on her Twitter account @Glastomichelle and on her website.