The rate of change within London is such that streets can take on a very different appearance within a matter of months, however it is unusual for a public park and old burial ground to disappear, however this has been the fate of St. James Gardens.

St. James Gardens are alongside Euston Station, between Cardington Street and Hampstead Road. They were used as a burial ground for the parish of St. James Piccadilly between 1790 and 1853. In 1887 the majority of the monuments and tombstones were removed and St. James opened as a public garden.

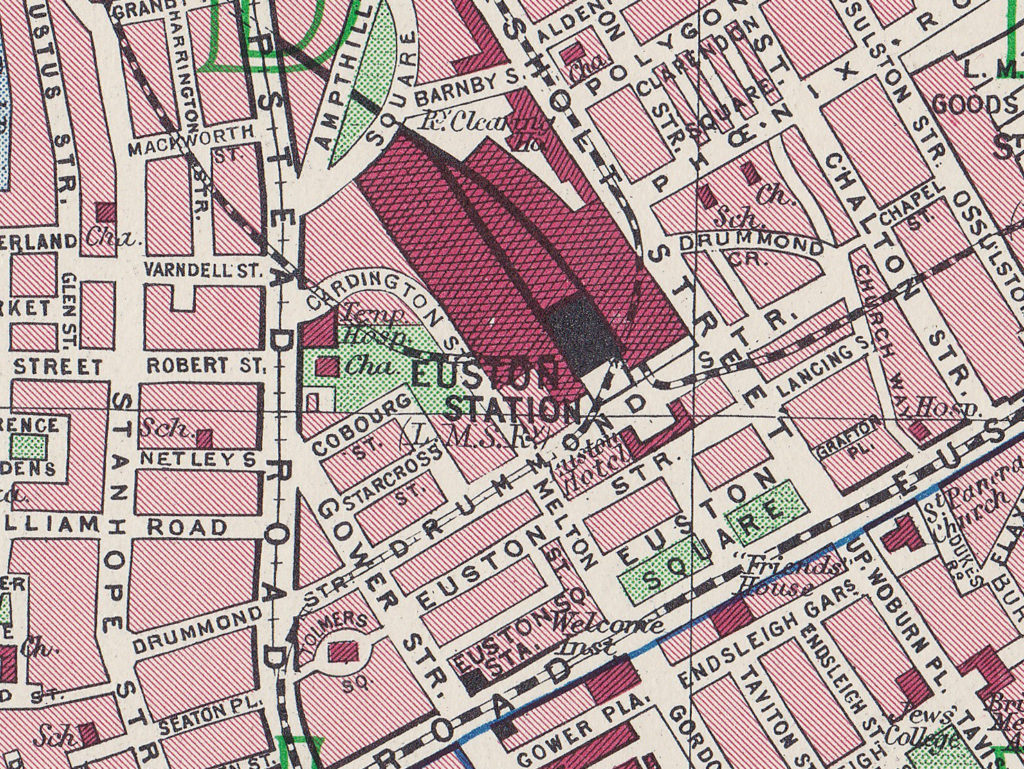

The location of St. James Gardens is the green space to the left of Euston Station in the map extract below from the 1940 Bartholomew’s Atlas of Greater London. I have used this map as the gardens have now disappeared from Google Maps (apart from an unlabelled small green rectangle). The gardens are still visible on Streetview which also has the ability to rollback to historic views of a location, however I believe this is not a feature with the basic map so it is interesting to consider how locations will be recorded long term if we rely on Internet mapping services.

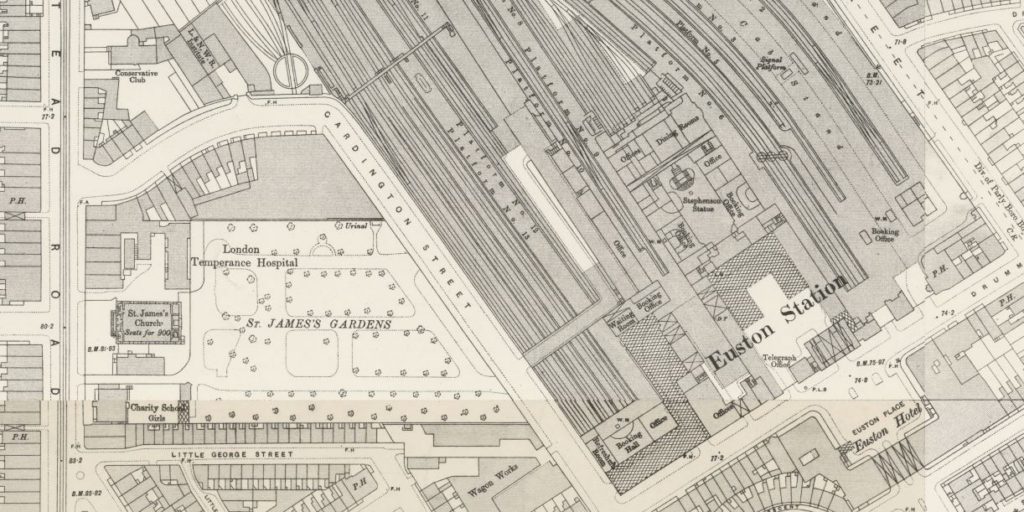

The following extract from the 1895 Ordnance Survey map clearly shows St. James Gardens and also shows how what was once a rectangular burial ground had already been cut through by Cardington Street and the original Euston Station.

The land occupied by St. James Gardens is needed for the expansion of Euston Station to accommodate HS2, so the gardens closed at the end of June to enable preparatory work to be undertaken prior to HS2 construction.

This will primarily involve the exhumation of the bodies buried across the gardens, the removal of the monuments that remain along with the trees that line the gardens.

I have seen various estimates for the number of bodies that are thought to be buried, anything between 30,000 and 60,000 which clearly means no one really knows, however it will be a major task for the exhumation and reburial of such as large number bodies. The first phase of work will be the excavation of archaeological trial trenches so that the scale of the task can be better understood.

A week before the planned closure, I managed to get down to St. James Gardens and photograph a historic space that will soon be lost from the landscape of London for ever.

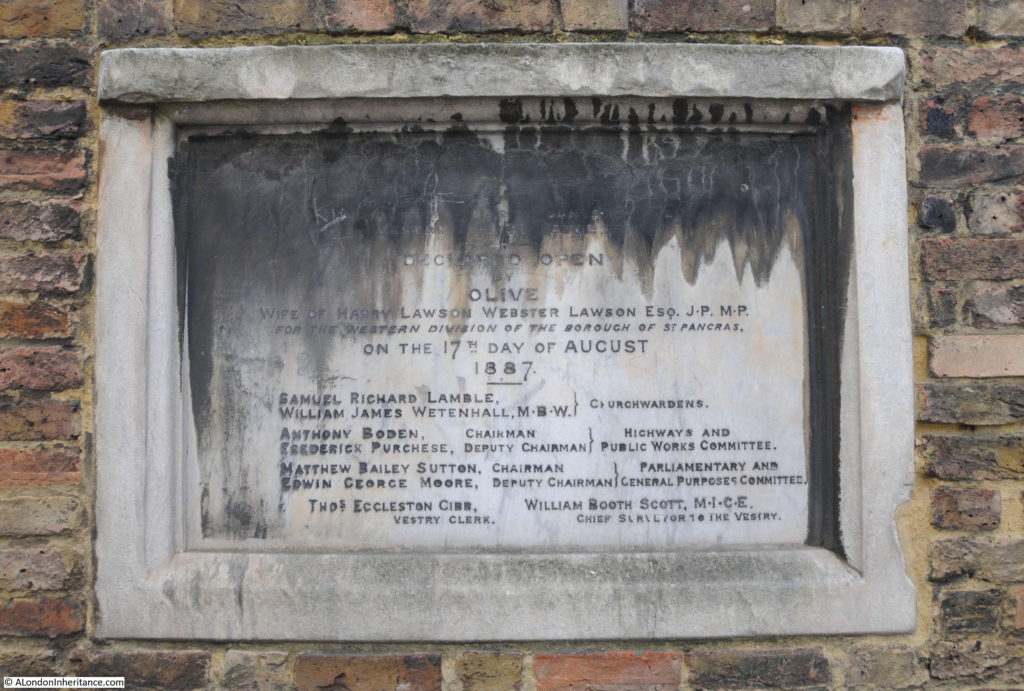

The plaque at the entrance from Hampstead Road recording the opening of the burial ground as public gardens on the 17th August 1887.

The Camden Council welcome sign:

The majority of the original gravestones and monuments were removed when the burial ground was converted into public gardens and only a few now remain. These were already fenced off. The HS2 statement of the archaeological work to be carried out across the garden states that the remaining gravestones and monuments will be recorded, then removed and safely stored. There is no indication of their long term fate.

View across the gardens:

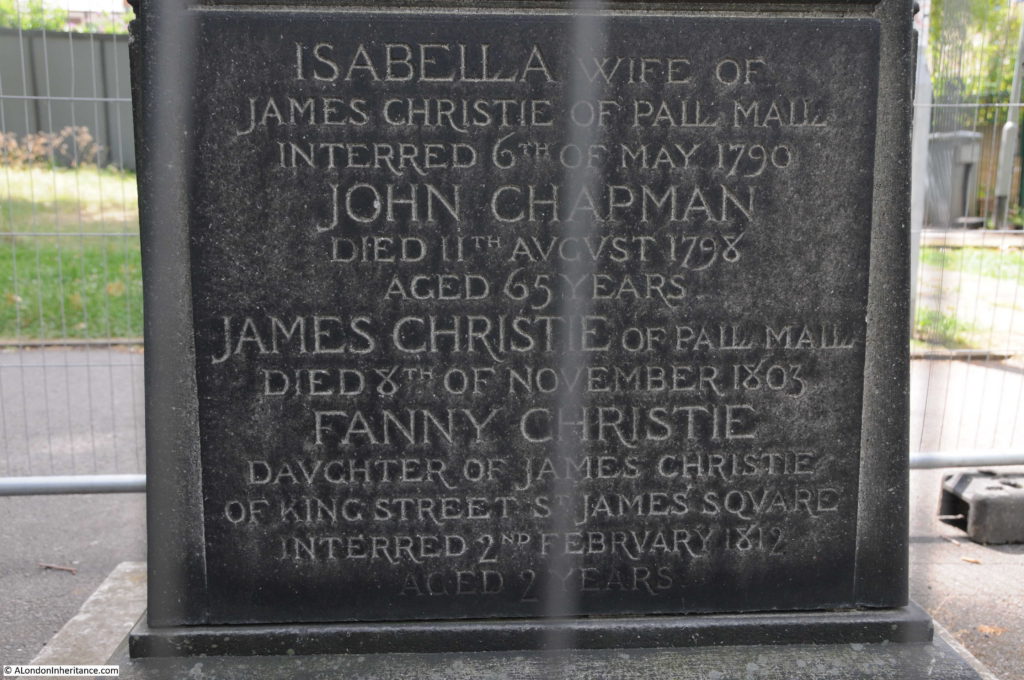

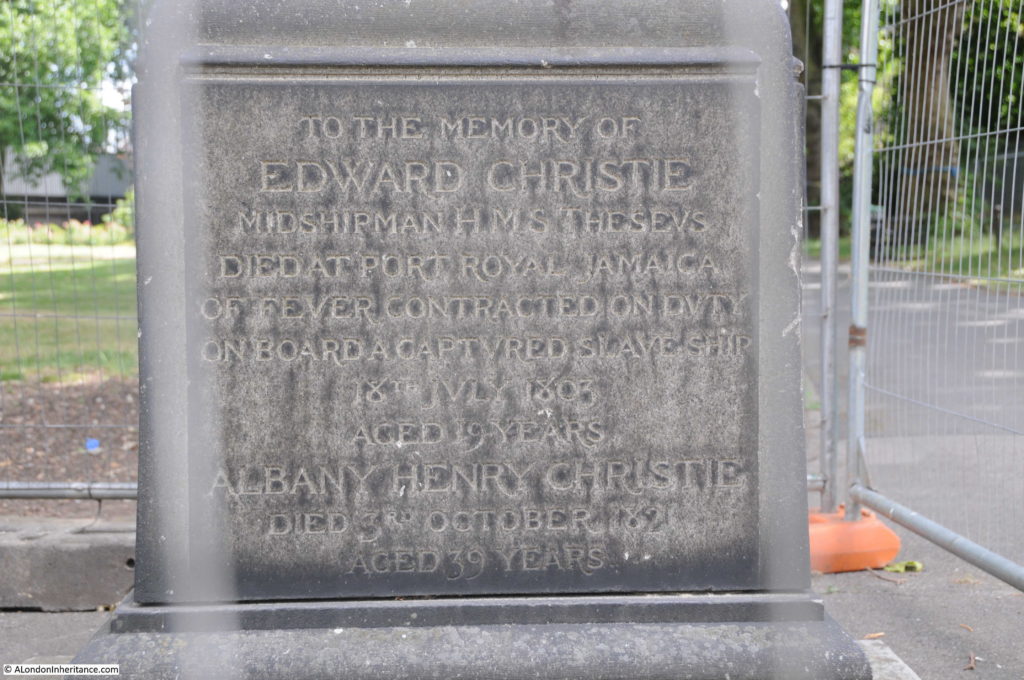

One of the most significant remaining monuments is that to the Christie family:

The memorial is to James Christie (the founder in 1766 of Christie’s auctioneer’s), who was buried in St. James Gardens. The memorial also records his wife and children (although I cannot find out who the John Chapman is, the only one on the memorial without a Christie surname).

John Christie, who was buried in St. James Gardens in 1803 (Source: Thomas Gainsborough [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

He had four sons, who are recorded on the monument. His eldest son, also James Christie took over the Auction business is recorded as are the other three who, I assume not being the eldest and therefore not inheriting the family business had to make their way in other professions.

Edward Christie is recorded as having been a Midshipman on HMS Theseus when he died at Port Royal, Jamaica of fever whilst on board a captured slave ship on the 18th July 1802, aged 19 years.

Albany Henry Christie is recorded as aged 39 when he died on the 3rd October 1821, but with no information on his profession or location, although I have found references to him being an articled clerk so he may have been in the legal profession.

The monument also records the death of his second son, Captain Charles Christie of the 5th Regiment, Bombay Native Infantry, killed in Persia by the River Aras in an attack made by a body of Russian troops on the 1st November 1812.

Captain Charles Christie had an adventurous life as part of the Bombay Regiment. In 1810, disguised as horse dealers, he was exploring a possible route through what is now Afghanistan and Iran to explore if a route was possible for European armies to invade India.

Christie was also part of an officer corp that entered Persian service following an 1809 treaty with the Shah of Persia. This included training Persian infantry and commanding one of the Persian regiments.

He was also involved in a number of military actions between Persia and Russia, as Russia was trying to take control of the area to the north of modern day Iran.

This involvement with Persia formally ceased in 1812 after an agreement between Great Britain and Russia, however a number of officers, including Christie, remained with the Persian army.

In a battle between the Persian and Russian armies in what is now Iran, Christie was shot in the neck, but refused to surrender and apparently killed six men before he was finally killed by the Russian forces. He was buried where he died close to the village of Aslan Duz which today is on the border between Iran and Azerbaijan on the River Aras.

The monument provides a snapshot of the careers of sons of the business and professional classes in the late 18th century. The eldest son would take on the family business, the route to financial success for the other sons would then often be the Navy, Army or Legal professions, as shown by the Christie family.

Unfortunately for Edward and Charles, their careers did not end with success, but with an early death a long way from home.

If you look back at the 1895 Ordnance Survey map shown above, you will see St. James Church between the burial ground and Hampstead Road. The print below from Old and New London shows the church facing a very rural Hampstead Road:

Edward Walford writing in Old and New London provides some more information on the church and who is buried in the burial ground, a location which does not get a very positive description:

“St. James’s Church, formerly a chapel of ease to the mother church of St. James’s, Piccadilly. It is a large brick building, and has a large, dreary, and ill-kept burial ground attached to it. Here lie George Morland, the painter, who died in 1804; John Hoppner, the portrait-painter, who died in 1810; Admiral Lord Gardner, the hero of Port l’Orient, and the friend of Howe, Bridport and Nelson; and without a memorial, Lord George Gordon, the mad leader of the Anti-Catholic Riots in 1780, who died a prisoner in Newgate in 1793.”

This was published in 1878 and the description of the burial ground as dreary and ill-kept probably explains why it was cleared and turned into public gardens in 1887.

View across St. James Gardens with some of the mature trees that will be lost:

Although the gravestones do not now exist, many of those who have unmarked graves in St. James Gardens played a significant part in late 18th and early 19th century history.

Captain Matthew Flinders, the navigator who led the first circumnavigation of Australia was buried here in 1814.

Lord George Gordon who led the protest from St. George’s Fields to the Houses of Parliament and which evolved into what became known as the Gordon Riots was buried here in 1793.

View over to the location of the London Temperance Hospital, the majority of which has now been demolished.

Walking around the gardens I found that the occasional solitary grave remains:

The mature tress have large, colourful cloths wrapped around their trunks. This was the result of a “yarn bombing” where hand knitted scarves are wrapped around the trunks of trees to draw attention to their fate.

The open space between the park and the Hampstead Road that was occupied by the London Temperance Hospital:

A few more of the remaining monuments and gravestones. The gravestone to lower right is to Catherine Griffiths and Griffith Griffiths along with their daughter Elizabeth and their son Daniel who is recorded as being drowned in the Thames on the 18th June 1852 at the age of 16.

View across the gardens from the edge of the gardens adjacent to Cardington Street:

Cardington Street on the left:

Cardington Street entrance to St. James Gardens with an HS2 poster announcing the closure of the gardens:

View across Cardington Street to the entrance:

St. James Gardens are now closed. Hoarding will hide the archaeological investigations across the site and the eventual removal of the monuments and the remains of those buried. St. James Gardens will eventually disappear beneath the development of Euston for HS2.

I hope that the few remaining memorials are moved to a location where they still have some relevance and with public access. It would be a shame if Captain Charles Christie, buried on the border between Iran and Azerbaijan, looses his remaining tangible connection with London.