Although today there is very little of it to see, water has shaped much of London. The alignment of streets, property boundaries, rise and fall of the land have all been shaped by water. Whilst these are all subtle indicators of the historic presence of water there are still a number of more visible signs that hint at an areas history, and one of these is on a building on the western side of King’s Cross Road.

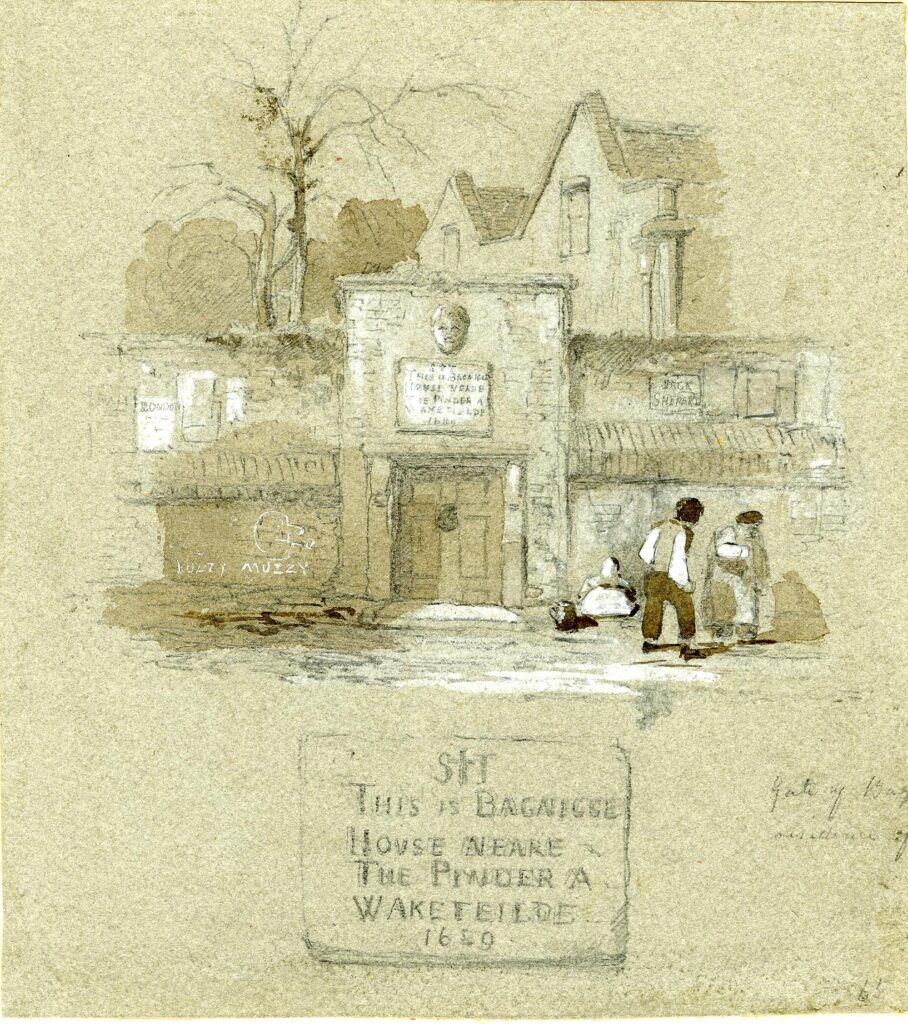

The sign reads “This is Bagnigge House Neare the Pinder A Wakefeilde 1680”.

The Pinder of Wakefield was a pub that dated back to the early 16th century in Gray’s Inn Road. A pub with the same name was on the same site until 1986, when the building was purchased by the “The Grand Order of Water Rats” charity, renamed the Water Rats, and is now a performance venue.

Bagnigge House and the Wells that were found in the gardens of the house are the subject of today’s post.

The house in King’s Cross Road with the Bagnigge House sign:

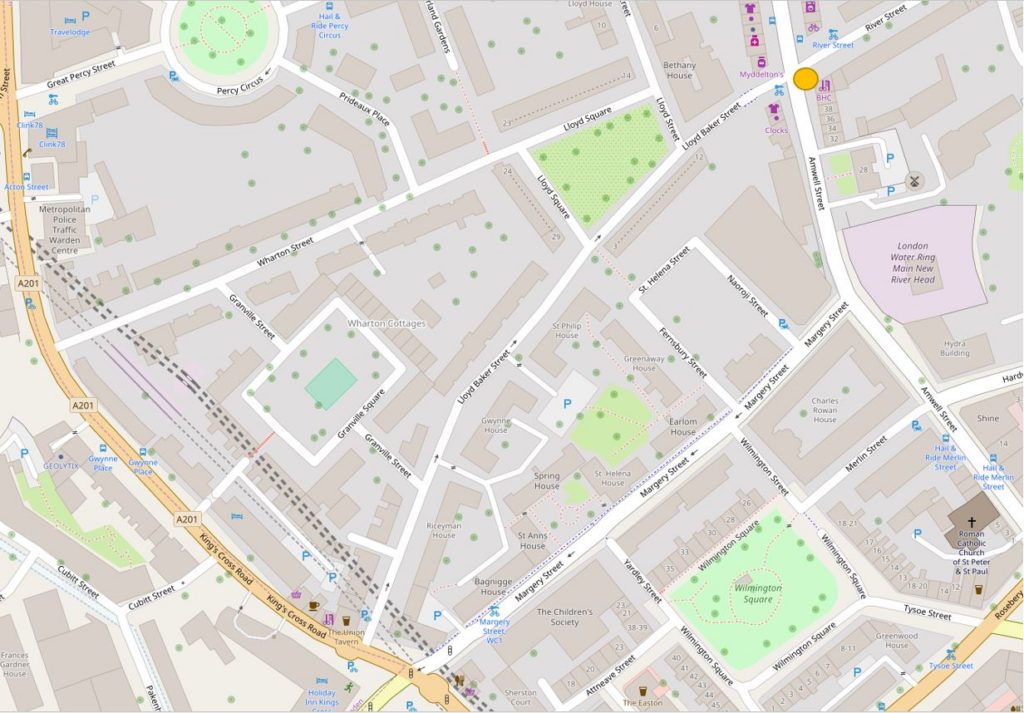

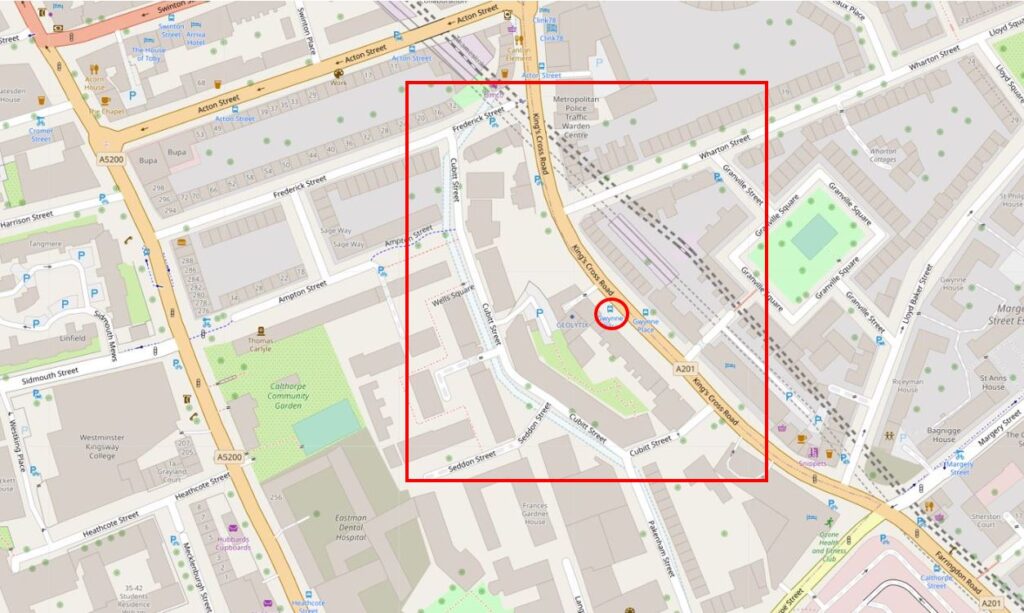

The location of the Bagnigge House stone, along King’s Cross Road is shown by the red circle in the following map (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

The red rectangle highlights the area covered in the post.

If you look to the left side of the red box, you will see Cubitt Street, a street which unlike the rest of the streets in the area, does not follow a straight line and is curved around an area of land between Cubitt Street and King’s Cross Road.

To the left of Cubitt Street, the map shows the light blue line of the old River Fleet. I have double checked with my go to reference for London’s old rivers; “The Lost Rivers of London” by Nicholas Barton and Stephen Myers, and the routing of the Fleet shown in the above map is roughly right.

Before the streets and buildings of London had extended this far north, this was an area of fields and agriculture. The River Fleet ran through the fields, the area was low lying and rather wet, especially after heavy rains when the Fleet would have flooded.

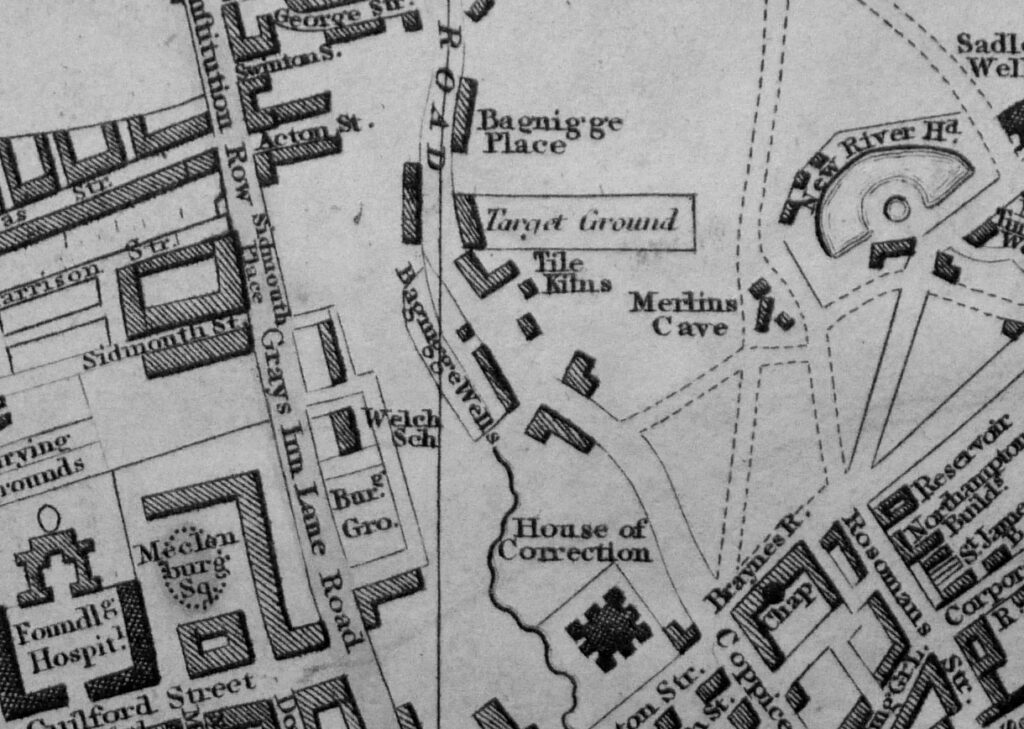

Rocque’s map of 1746 provides a view of the area in the middle of the 18th century. Fields cover the majority of the area, but in the upper centre of the map there are buildings and formal gardens bounded by the River Fleet and a street named Black Mary’s Hole.

The street to the left labelled “Road to Hampstead and Highgate” is today, Grays Inn Road.

Black Mary’s Hole is now King’s Cross Road. There are various interpretations of the name, but the majority of sources refer to a black woman called Mary, who sold water in the vicinity from a well or fountain.

As well as the Fleet, the Rocque map extract also shows the irregular shape of a number of ponds, confirming that this was an area where there was plenty of water.

By 1816, streets and buildings had started to reach the area, and the following extract from the 1816 edition of Smith’s New Plan of London shows the area between the Fleet and King’s Cross Road (in the centre of the map) now labelled Bagnigge Wells.

To the right of the map is New River Head and on the edge of the map, Sadler’s Wells, further illustrating how water has shaped the area.

Turning off King’s Cross Road into the side streets, and we can get a view of the drop in height down to King’s Cross Road and the rise in height on the opposite side. An indication of the river valley of the Fleet.

The following view is looking down Great Percy Street from Percy Circus, with the rise of Acton Street across the junction. The River Fleet would have run from right to left along the lowest part of the view.

The area of land shown in the Roque map between the Fleet and Black Mary’s Hole appears to have been enclosed at some point in the second half of the 17th century. The land was to the east of a field called Action Field that occupied the area west to what is now Gray’s Inn Road. The name of the field is preserved in the present day Acton Street.

When a Thomas Hughes purchased the land in 1757, he had the waters from a well that was already in use, tested by a Doctor John Bevis, who reported that the water from the well had chalybeate properties (in the context of water, the name chalybeate means that the water contains iron, see also my post on the Chalybeate Well in Hampstead).

To capitalise on these findings, Thomas Hughes opened the gardens and the well to the public in 1759. This was the period when there were many pleasure gardens opening up around the City. Outside the jurisdiction of the City of London, in places such as along the south bank of the Thames, in Islington, and in Bagnigge Wells.

They provided a pleasant place to visit, away from the smoke, dirt and noise of the City. St. Chad’s Well was another well a short distance away from Bagnigge Wells that had gardens and a pump house where customers could drink the water. I have written about St. Chad’s Well here.

The gardens around the well were attractively laid out, entertainment, food and drink was also provided to customers, both to attract customers to the gardens as well as for profit.

Bagnigge Wells seems to have been a success as some of the land on the opposite side of the River Fleet was purchased to expand the gardens.

A print from 1843 appears to show the stone that is now in King’s Cross Road above the garden entrance (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

The inscription on the stone in my photo at the top of the post has the date 1680. In the print above it could be 1689, so either an error, or a later updating of the inscription over the years has changed the original date on the stone.

The date does pre-date the time when the gardens and well were part of the pleasure gardens so the house referred to must have been one of the earliest houses on the land.

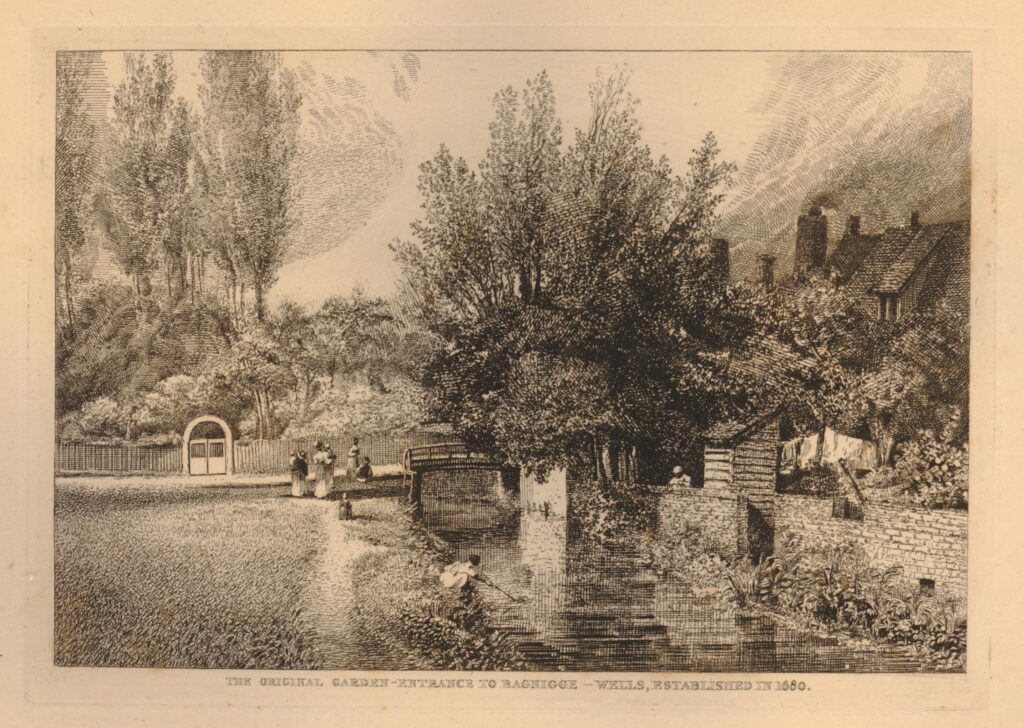

Although the caption to the following print does state “The Original Garden Entrance To Bagnigge Wells, Established in 1680”, the gardens and wells were not a public gardens at that time (© The Trustees of the British Museum).

Presumably, the view is looking north with the garden entrance on the left and Bagnigge House behind the trees on the right.

The river running along the middle of the print must therefore be the River Fleet, which looks rather serene and calm, however it was not always so, and heavy rains around the source of the river in Hampstead could quickly result in the river flooding as the following article from the Derby Mercury on the 9th September 1768 reports:

“And about One o’clock yesterday morning the water came down in such torrents from Hampstead that the road and flat fields about Bagnigge Wells were overflown; the water rose eight feet perpendicular above the usual height of the drain, and was nearly four feet above the foot bridge at that house; the Pleasure-garden, cellars, and Out-houses belonging thereto were overflown, and several of the Pales broke down by the Violence of the stream. Great damage was done to Mr Harrison’s Tile-kiln near the said Wells, where three young men were sleeping in an Out house and were surprised by the Flood, and two of them drowned. The house of Dr. Sharpe, near Bagnigge Wells, was four feet deep in water, and a man and woman behind the House narrowly escaped being drowned.”

The article mentions Mr. Harrison’s Tile-kiln and if you refer back to the extract from Smith’s New Plan of London, you can see the tile-kilns just to the north east of Bagnigge Wells.

The rain was probably caused by the brief, very heavy showers we have also seen in London recently which cause a flash flood. Today, this volume of water falling in north London would now be carried by the same sewer in which the old River Fleet in now buried.

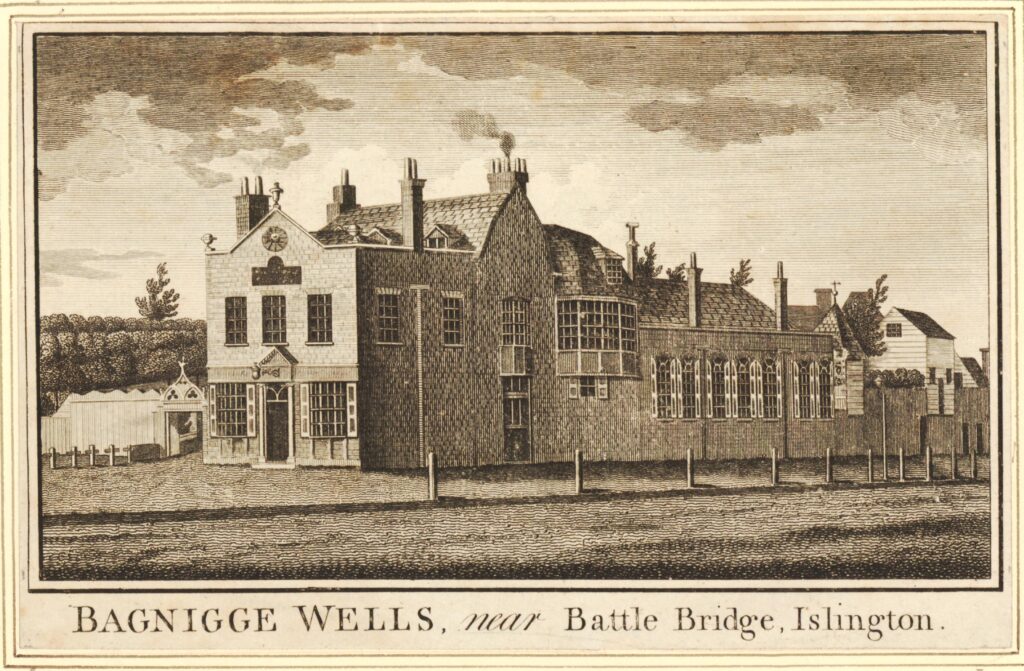

The following print is from 1777, eleven years after the floods in the above article and shows the buildings at Bagnigge Wells, with the entrance to the gardens on the left (© The Trustees of the British Museum).

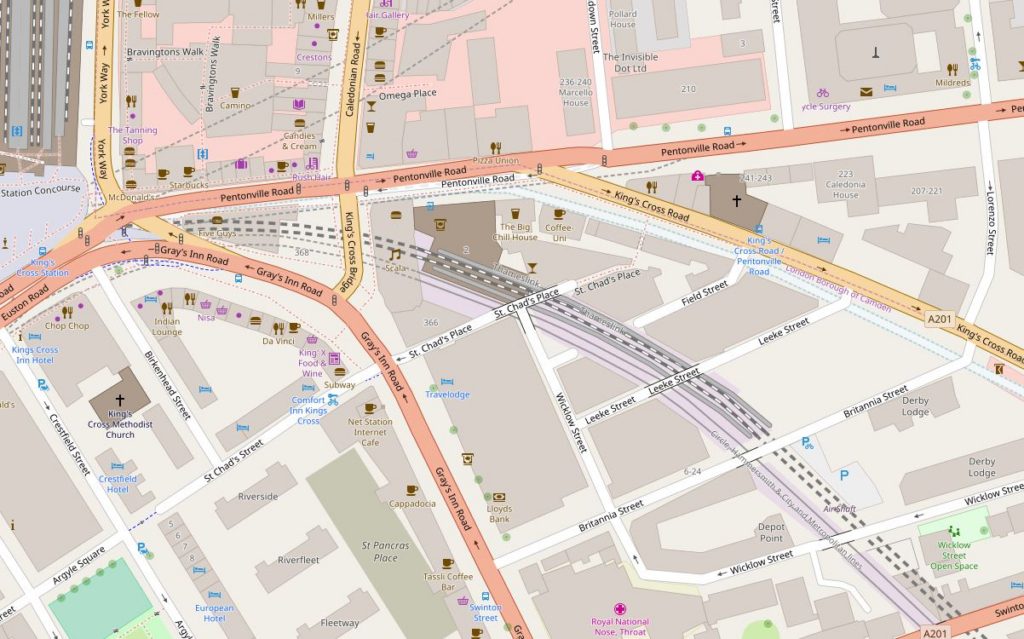

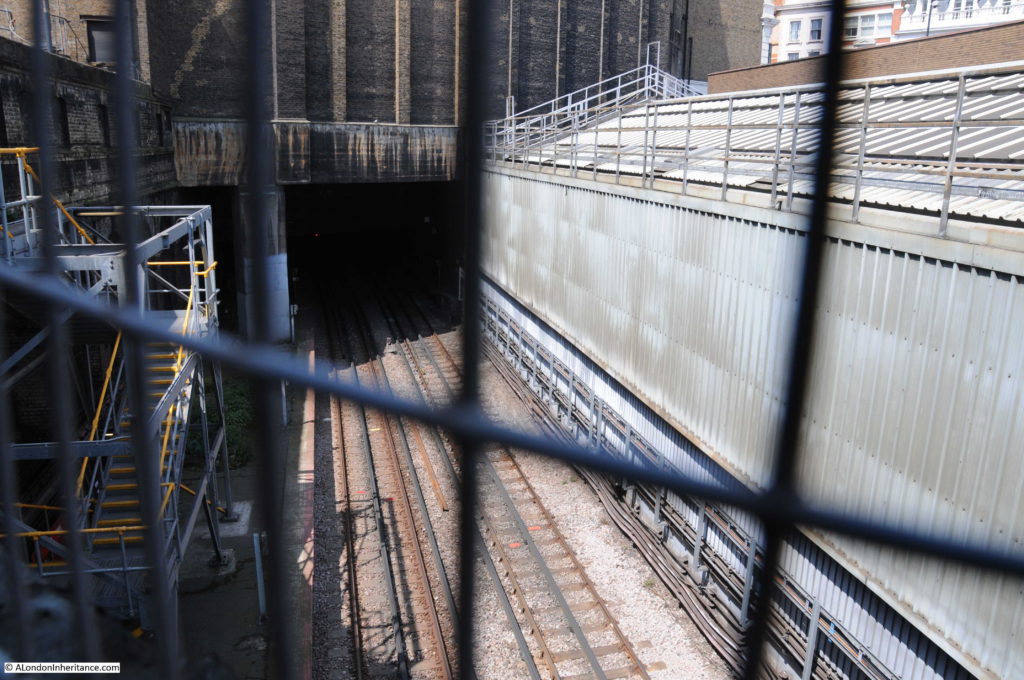

Today, roughly where the River Fleet once ran, is Cubitt Street (originally Arthur Street). This is the street that curves slightly to the west of King’s Cross Road and is where the River Fleet formed the original western boundary to Bagnigge Wells as shown in Rocque’s map of 1746,

The view south along Cubitt Street:

And the view north along Cubitt Street:

In the above view, the River Fleet would have run roughly along the line of the street. Bagngge Wells was originally to the right, and following the commercial success of the gardens, expanded to include the left of the photo, with wooden bridges providing access between the two sections of the gardens.

Seats were arranged along the River Fleet for those who wanted to smoke or drink ale or cider. Tea, cake and hot buttered rolls were served, and concerts were held in the main room of the house. A small temple shaped building was created to house the wells from which water was taken and sold.

London’s pleasure gardens and their visitors were often the subject of satirical prints. The following print from 1781 shows “Mr. Deputy Dumpling and Family enjoying a Summer Afternoon” at the entrance to the gardens at Bagnigge Wells (© The Trustees of the British Museum).

18th century pleasure gardens were intended to be peaceful places in London’s countryside, away from the noise and dirt of the City. Where people could spend an afternoon or evening, being entertained, or just drinking and eating and seeing and being seen by others at the gardens, however they were not always places of peace.

in May, 1784, Bagnigge Wells was the scene of some violence between two opposing political groupings, as documented in the following newspaper report:

“Yesterday evening the gardens at Bagnigge Wells exhibited a strange scene of riot and confusion. How the affair began is not easy to be determined, but, at the same moment, several hundreds of Stentorian lungs vociferated the cry of ‘Hood and Wray’ and these were answered by the exclamation of ‘Fox for ever’. Intoxicated with liquor and politics those who were for Hood and Wray boxed with the friends of the Coalition and Fox, and many on both sides were knocked down with the canes and sticks of their adversaries. So sudden a disarrangement of the tea-table apparatus was perhaps never before seen and innumerable fragments of china shone on every walk, and served to give issues to the inflamed blood of the fallen and sprawling heroes. Those peace officers were sent for, the tumult was not appeased for near two hours and a half. Three men, who had been active in fomenting the disturbance, were taken into custody and were soon rescued”.

The same newspaper also reported on a “violent fracas” between the same two opposing groups in the Piazzas, Covent Garden.

Wray was Sir Cecil Wray who was a member of Parliament but was highly critical of proposals to raise taxes by a “receipts tax” which he claimed would fall “on the middling ranks of people and very partially and unequally laid”. Wray preferred a land tax, which in his view had always been too low in the country, but was opposed by the land owning classes (some things do not change).

He also presented a petition that had been drawn up by the Quakers calling for the abolition of slavery, which he called “an infamous traffic that disgraced humanity”.

The MP Charles James Fox put forward the East India bill which proposed nationalising the troubled East India Company, and Wray was strongly opposed to such an action.

At the general election Wray and Lord Hood stood against Fox with Wray standing as an Administrative candidate in Fox’s Westminster constituency. It was a violent election period as indicated by the trouble at Bagnigge Wells, however Fox won and Wray then appears to have abandoned any plans to try and get back into Parliament. He was described as being “one of the most upright, one of the most virtuous, one of the most honourable and independent men” in Parliament.

Up until the end of the 18th century, Bagnigge Wells continued to be a fashionable place to visit, however its days were numbered as the buildings and streets of London started to surround the gardens.

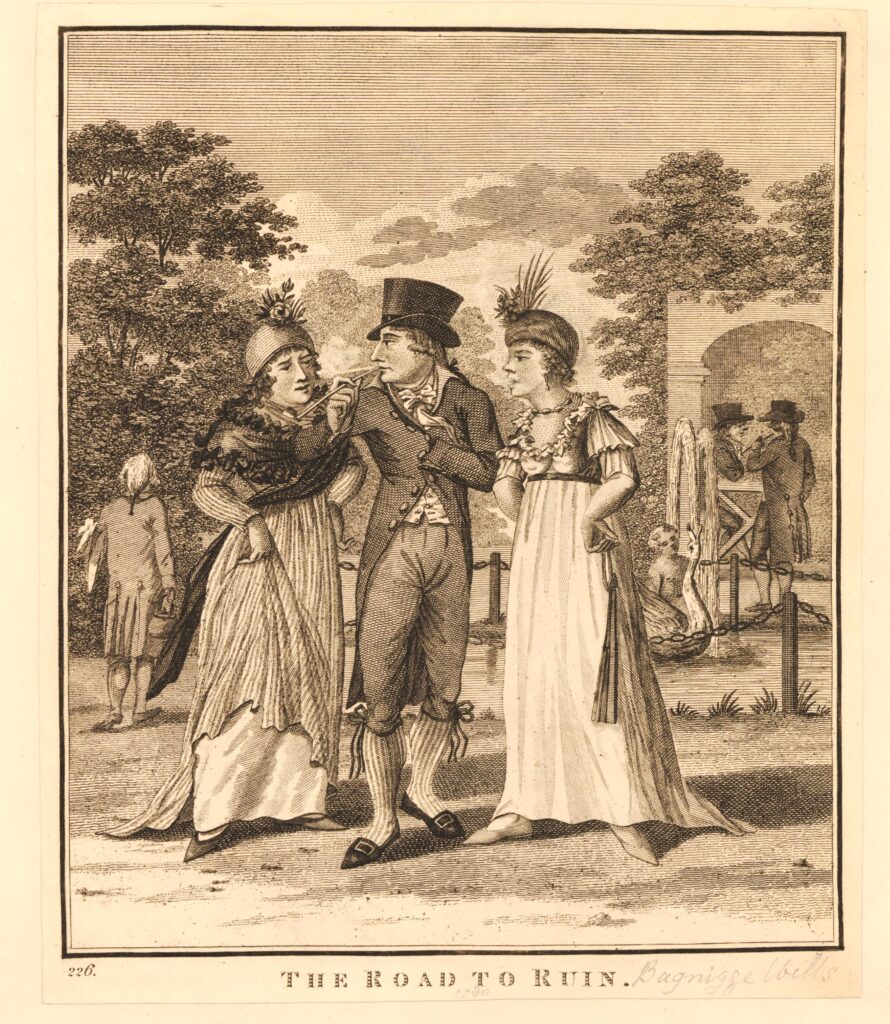

Less desirable and the “lower class of tradesmen” were now to be found in the gardens, and there was petty crime and prostitution, as illustrated by the following print from 1799 titled “The Road To Ruin”, where a young man, possibly an apprentice, in poor fitting clothes, stands between two prostitutes who appear to be berating him (© The Trustees of the British Museum).

In 1813, the manager of the gardens went bankrupt, they reopened somewhat reduced the following year and attempts to rejuvenate the place by building a concert hall in 1831 led to nothing as the customers of the concert hall were described as being of the “disreputable sorts”. The concert hall closed in 1841 and what was left of Bagnigge Wells was built on.

With the River Fleet now buried in a sewer, there are today no signs above the surface of the waters that once made this area an attractive place to visit, away from the noise and dirt of central London.

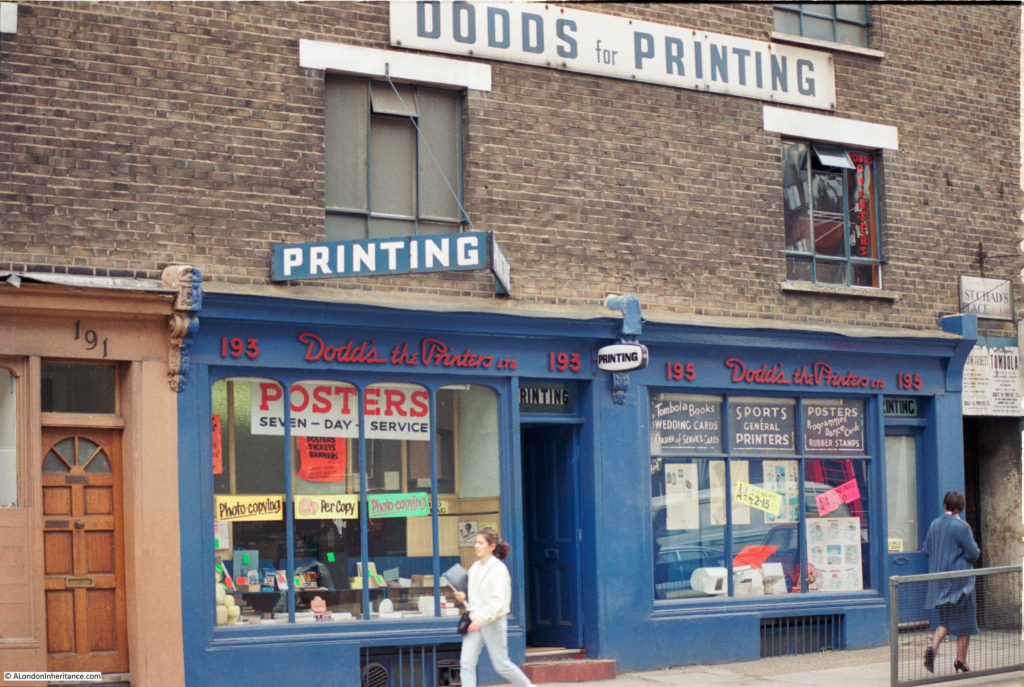

I have photographed the plaque before, however there was a bus stop directly in front which made the plaque rather difficult to photograph. The following photo is from about 18 months ago and shows the bus stop in its original position.

If you refer back to the second photo from the top of this post you can see that the bus stop has now been moved to the right. No idea why this has been done, but it does make the plaque easier to see, which is to the good, as it is the only reminder of Bagnigge House, the Well and Gardens now to be found in the area.