On the South Bank, where York Road meets the large junction with Westminster Bridge Road, and just south of Waterloo Station, there is a building that today stands out among the surrounding new hotels. This is the General Lying-In Hospital, an institution founded in 1765 by Dr John Leake.

The building we see today was constructed in 1830, after the death of Dr John Leake, however it is here because he was instrumental in founding the first dedicated maternity hospital, which originally was a very short distance away on Westminster Bridge Road.

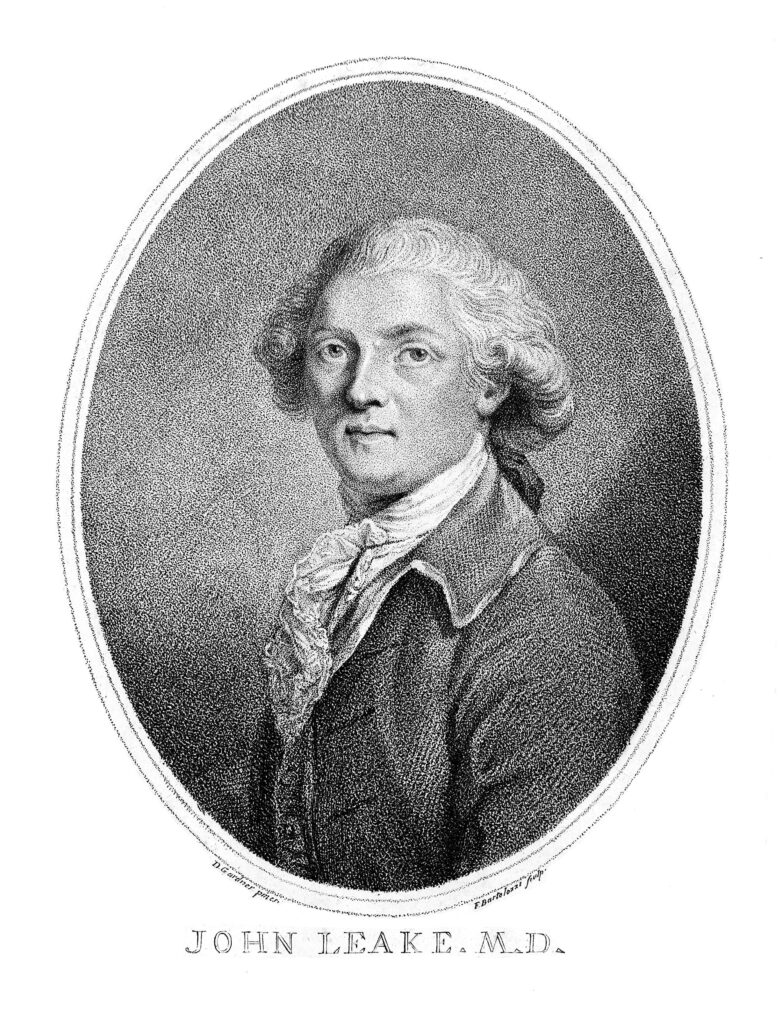

John Leake was born on the 8th June 1729 at Ainstable in Cumberland. There is not that much written evidence of his early life, however he went to Bishop Auckland Grammar School, and became a Doctor of Medicine at Rheims at the age of thirty four, and was admitted to the College of Physicians three year later.

In the mid 18th century, the requirements for entry to the medical profession were rather basic. The ideal candidate was a “cultured and highly educated gentleman”, who only needed an adequate knowledge of medicine. One could become a Doctor via an apprenticeship, and a physician would need only one year’s training in medicine, although up to 1812, the College of Physicians required only six months hospital practice.

There is no record as to how Dr John Leake became interested in child birth, but on Wednesday the 7th of August 1765, he was calling together a meeting of the sponsors of the new hospital at Appleby’s Tavern in Parliament Street.

The new hospital was to be called the Westminster New Lying-In Hospital, and at the meeting Leake reported that sufficient funds had been received to purchase a plot of land for the new hospital, on Westminster Bridge Road, probably today under the railway bridge leading into Waterloo Station.

Dr John Leake:

The new hospital was to be for “the Relief of those Child-bearing Women who are the wives of poor Industrious Tradesmen or distressed House-keepers, and who either from unavoidable Misfortunes of the Expenses of maintaining large Families are reduced to real Want. Also for the Reception and Immediate Relief of indigent Soldiers and Sailors Wives, the former in particular being very numerous in and about the City of Westminster”.

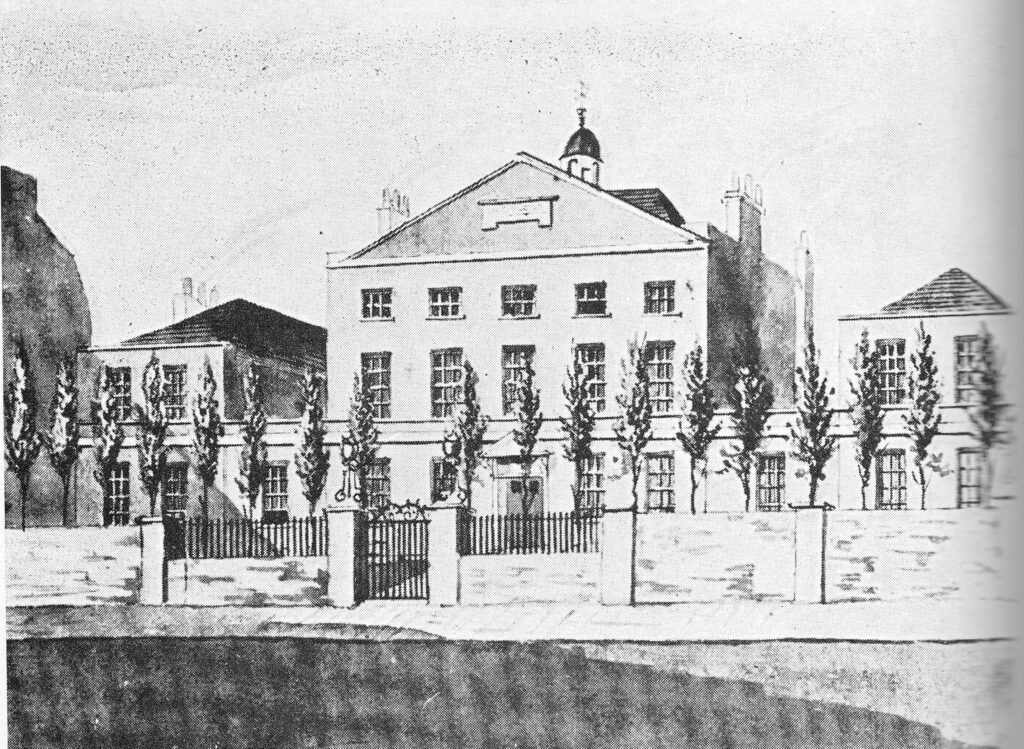

The first stone of the new hospital was laid on the 15th August 1765 during a Governors visit to the building site. A view of the hospital when complete:

The location of the original hospital is shown in the following extract from Smith’s New Plan of London from 1816:

In 1766, there were problems with cash flow and raising sufficient funds to complete the hospital. As well as subscriptions from individuals, events were planned, including a benefit play. The play appears to have taken place at Covent Garden on Boxing Day, 1766, when £114 was raised. There had also been an earlier benefit play at Drury Lane Theatre.

Dr John Leake must have been very busy during the 1760s. As well as the challenge of funding and building the new hospital, he was also a practicing doctor as well as training and lecturing. An advert in the papers of 1767 provides a view of how his lectures were carried out:

“On Monday the 5th October next, at seven in the Evening, will begin, A Course of Lectures on the THEORY and PRACTICE of MIDWIFERY, and the Diseases of Women and Children, in which the true principles of that Science will be distinctly laid down and the several Operations clearly demonstrated, by an artificial representation of each difficult Labour, upon Machines of a new Construction, exactly resembling Women and Children.

By John Leake M.D. Member of the Royal College of Physicians, London and Physician Man-Midwife to the Westminster New Lying-In Hospital. Where the Students for their more expeditious and effectual Improvement, will be admitted to attend as Pupils.”

The title “Physician Man-Midwife” for John Leake came into force on the 2nd June 1767 when he was unanimously elected to the position, as the first medical appointment for the new hospital.

Whilst the earlier statement about who would be admitted to the hospital implies quite an open policy, it did require an introduction from a subscriber and a standard letter had been prepared where a subscriber would request a named person to be admitted as a patient and was “an Object worthy of Charity”.

Governors would have to approve an introduction, and as in the mid 18th century anti-natal care was almost non-existent, Governors would only admit a patient in their last month of pregnancy.

Between the 20th April 1767 and 20th April 1769, the hospital had delivered 218 babies, three of which had been still born. The hospital had an infant death rate of 90 per 1,000 births, and a maternal mortality of 4.7 per 1,000 births. Very much higher than today, but believed to be considerably better than giving birth outside of such an institution.

The hospital would only allow women entry in the last month of their pregnancy. This resulted in over ten percent of women who had been approved to give birth in the hospital, not attending as they had delivered at home, prior to the last month. There is no record of the results of such home births.

An ongoing problem for the hospital came from the Parish in which the hospital was located. At the time, the Parish would become responsible for children where the mothers could not support them, and on the 6th December 1769, Lambeth Parish made a complaint to the hospital about ten children born in the hospital who had become chargeable to the parish.

It even appears that some mothers were claiming their babies had been born in the hospital to get the support from the parish, as the parish were checking names with the hospital to confirm they had been a patient.

Dr John Leake died in 1792, and newspapers on the 16th August carried a rather simple notice of his death: “Yesterday died, in Parliament Street, Dr John Leake, Physician to the Westminster Lying-In Hospital, of which he was the founder, and the author of several useful publications”.

It was a rather underwhelming tribute given his achievements, the main one being instrumental in setting up the hospital.

After John Leake’s death, there were a number of months when the hospital went through an unsettled period. People competed for positions within the Governors and for medical appointments in the hospital, and new management started to change some of the hospital’s processes, however by mid 1793, the hospital had settled down into a new phase of running without the key founder.

A critical issue for the hospital for the following few decades seems to have been having sufficient funds to maintain operations, with regular appeals for donations and subscribers.

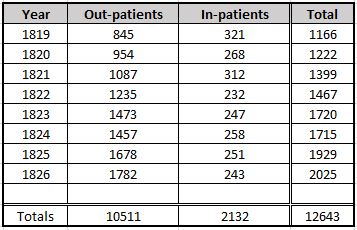

A report at the start of 1827 provides an indication of the number of patients both within the hospital, and being seen as out-patients:

By the early 1820s, there was a need to find a new location for the hospital. The existing site had a complex set of leases with different owners, which each had to be renewed at different times. The old building was also becoming unsuitable given advances in midwifery and maintaining hygiene within a hospital environment.

After some searching, a site was found, that would become the site of the hospital we see today. To help with funding, more subscribers were needed, and the search for subscribers sheds some light on how they were involved with the selection of patients “That is future Subscribers of Twenty Guineas at one payment be allowed to recommend yearly two in-patients and two out-patients and one for advice”. Ten guinea subscribers could only recommend one patient for each of the categories.

The move to the new hospital seems to have taken place in 1828, however the hospital has the date 1830 on the far right of the façade in the photo below. This seems to be when the Common Seal was affixed to the lease for the land which had been given by the Archbishop of Canterbury. By this time, Westminster had also been dropped from the name of the hospital and it became simply the General Lying-In Hospital.

Care during pregnancy during the first half of the 19th century was almost non-existent. Recognition of complications during pregnancy was very limited unless such complications were catastrophic. Standards of hygiene were poor in many of the Lying-In Hospitals. Many of the approaches to complications were horrendous and carried out without anesthetic. The mortality rate for Caesarian section was dreadful. Of the fifty-two operations carried out in 1838, only thirteen women survived.

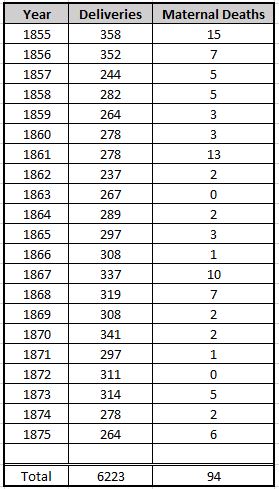

The General Lying-In Hospital published numbers of deliveries and maternal deaths for the years 1855 to 1875, as shown in the following table:

The figures recorded by the hospital do not state whether a delivery was a single child, or whether a delivery covered twins where these were born.

Assuming each delivery is a single child per mother, then the average death rate of mothers was fifteen per thousand. For comparison, I checked the World Bank statistics for Great Britain, and today the mortality figure is seven per 100,000 live births. A phenomenal improvement since the first half of the 19th century.

Many of the problems with child birth in the first half of the nineteenth century were not just through medical complications, but were caused by the level of poverty that was effecting so many of London residents at the time. Malnutrition and rickets resulted in a disproportionate size of fetal head and that of the pelvis. This resulted in many cases of difficult delivery.

The rates of child mortality were also high, and whilst the working population was most effected due to poor diet, housing conditions, poverty etc. child death also affected all levels of society and could influence history.

When King William IV died in 1837, he had no legitimate heirs. His wife, Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen had suffered the death of five children. Three, including twin boys were stillborn and two died within six months of birth. Perhaps because of these deaths, Queen Adelaide was a sponsor of the General Lying-In Hospital, contributing £10 per annum to the charity.

As William therefore had no legitimate heirs, the crown would pass to Victoria, who would reign from 1837 to 1901 and stamp her name on two thirds of the 19th century, a significant period of the industrial revolution, and when the basics of the modern world were formed.

Above the main entrance to the hospital is an inscription – “Licensed for the public reception of pregnant women pursuant to an Act of Parliament passed in the thirteenth year of the reign of King George the Third”.

This act, passed in 1773, long before the new hospital building was constructed, attempted to address the problem with local parishes objecting to taking on the expense of illegitimate babies, by making the Governors of such hospitals apply for a licence to continue. The hospital could therefore claim that it was operating legally under an Act of Parliament.

The issue of unmarried mothers had long been troubling for the hospital and in 1774 the Governors decided to exclude unmarried mothers from the hospital, however to moderate this decision, the Governors retained the ability to admit unmarried mothers at their discretion.

The second half of the 19th century did see considerable improvement in the practice of midwifery, hygiene, and general medical practice, and at the start of the 20th century we can get a remarkable glimpse into the life of the hospital.

When researching this post, I found a series of photographs of staff at the hospital in 1908, held by the Wellcome Collection. Fortunately these can be used under a Creative Commons licence.

General Lying In Hospital, York Road, Lambeth: nurse sitting with baby in incubator. Photograph, 1908.. Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)

The nurse in the above photo is shown in a second photo in a far more relaxed pose, holding one of the babies in her care. It is a wonderful photo from 1908:

General Lying In Hospital, York Road, Lambeth: nurse sitting holding baby. Photograph, 1908.. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

The General Lying-In Hospital had run training sessions, which included work at the hospital, since Dr John Leake had originally founded the hospital and the following photo from 1908 shows the Labour Ward Nursing Staff and Pupil Midwives:

General Lying In Hospital, York Road, Lambeth: labour ward staff and students. Photograph, 1908.. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

A larger group of hospital staff:

General Lying In Hospital, York Road, Lambeth: hospital staff. Photograph, 1908.. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

As well as the hospital staff in the above photo, look at the central window in the rear of the photo, and there are a couple of faces looking at what is happening on their neighbouring building:

A smaller group photo:

General Lying In Hospital, York Road, Lambeth: group of nurses. Photograph, 1908.. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

In a similiar way to the faces in the window in the earlier photo, look to the right edge of the above photo and there is someone sneaking a look at what is going on.

Weighing a baby:

General Lying In Hospital, York Road, Lambeth: nurses weighing a baby. Photograph, 1908.. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

Another smaller group photo, this time of the senior staff of the hospital. The woman on the right of the photo is the same nurse / midwife as in the first two photos.

General Lying In Hospital, York Road, Lambeth: senior staff. Photograph, 1908.. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

Unfortunately there is only one photo that records the name of those in the photo. This is Nurse Woodyer (note the scissors tucked into the belt):

General Lying In Hospital, York Road, Lambeth: nurse Woodyer. Photograph, 1908.. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

By the time of the above photos, the treatment of patients had improved considerably. This included the use of anesthetic. There had been much clerical objection to the use of pain relief during labour – no doubt from those who did not have to suffer such pain, however the use of anesthetic during child birth gained popularity after Queen Victoria used chloroform for births in 1853 and 1857.

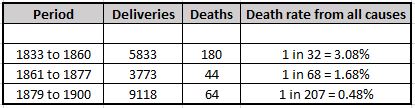

There were still challenges, for example in 1877, the hospital was suffering high mortality rates of 1 in 19. The cause was believed to be overcrowding, dirty linen and poor ventilation. Recommendations to address these problems included moving the toilets outside of the main building, replacing sacking which had been used on the base of bedsteads with iron battens, more space between patients and improved ventilation.

Despite the challenging issues in 1877, the 19th century saw gradual improvements in care, as the following table of the maternal death rate shows;

As had been the practice of the hospital since founding, there was a continual training programme and in 1907, the numbers trained covered 33 Midwives, 83 Maternity Nurses, and in the district for house calls, 16 Maternity Nurses had been trained.

The procedure whereby subscribers could recommend patients had been in force since the opening of the hospital and lasted a remarkably long time. It was only in 1922 that the Governing Committee decide to abolish the use of the procedure, however probably to keep subscribers financial support, they still had a route where they could apply to the Lady Almoner of the hospital if they had a patient they wanted to recommend.

The hospital did try to run an open access approach, however as seems to have been the problem since opening – funds were always tight and additional support was always wanted.

In the early decades of the 20th century, the General Lying-In Hospital had been expanding. There was a Post-Certificate School in Camberwell for advanced training, and the hospital had opened up a unit at St. Albans, and it was the St. Albans operation which grew in use from 1940 when 50 patients a month were being transferred from York Road to St. Albans due to the dangers of bombing.

The end of the General Lying-In Hospital in its charitable form came with the National Health Service Act of 1946, when the hospital became part of the NHS in July 1948. The hospital was no longer dependent on subscribers and charitable donations, and the Board of Governors was disbanded.

The Ministry of Health had arranged for the General Lying-In Hospital to come under the Board of Governors of St Thomas’s Hospital, and an indication of the future loss of independence came in 1949 when the hospital was informed that it would become part of the Obstetric and Gynecological Department of St Thomas’s Hospital.

St Thomas’s was also the site where all new high-tech diagnostic equipment would be housed, so the long term future of the General Lying-In Hospital was starting to look rather limited.

in the mid 1960s there were three local hospital’s with facilities for child birth. Lambeth and St Thomas’s as well as the General Lying-In Hospital. The late 1960s also saw a reduction in the number of births and the number of children born per mother was also decreasing. Changing social attitudes, increased use of contraception and the introduction of the contraceptive pill in 1961, initially for married women, but generally available for all from 1967 resulted in the viability of three hospitals for child birth being questioned.

The end of the General Lying-In Hospital came in 1971 when the hospital closed, and services moved to St Thomas’s.

Today, the building is part of the adjacent Premier Inn, and although there is a Premier Inn sign on the side of the building, there is no plaque or sign commemorating the founder of the hospital – Dr John Leake.

To find Dr John Leake’s name we must walk a short distance from the General Lying-In Hospital.

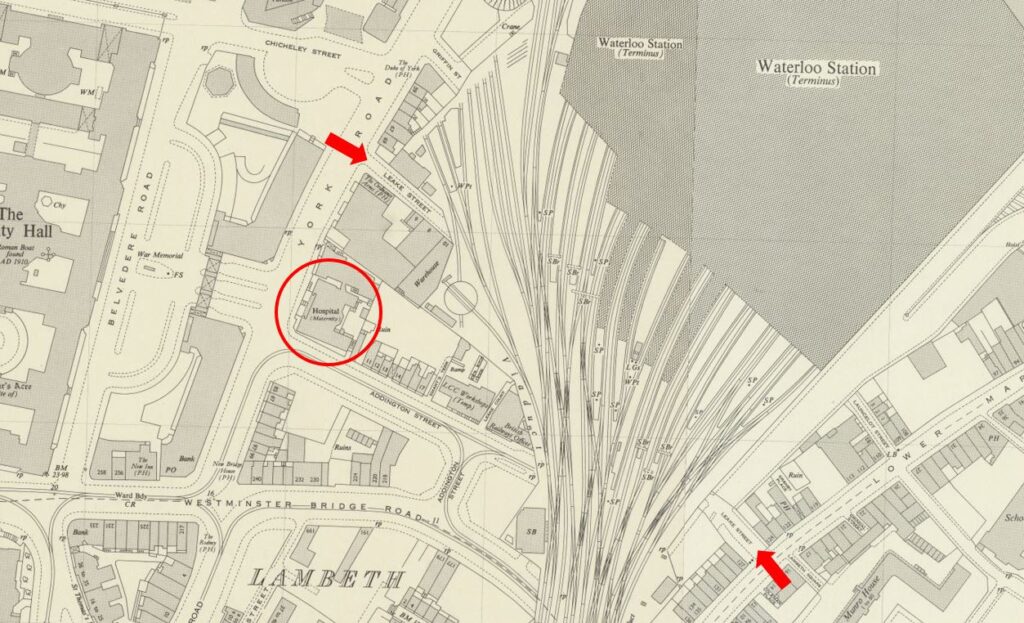

I have circled the location of the hospital in the following extract from the 1895 Ordnance Survey Map (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’.

I have also marked the start and end points of York Street with two red arrows. Part of the street passes under the rail tracks leading into Waterloo Station.

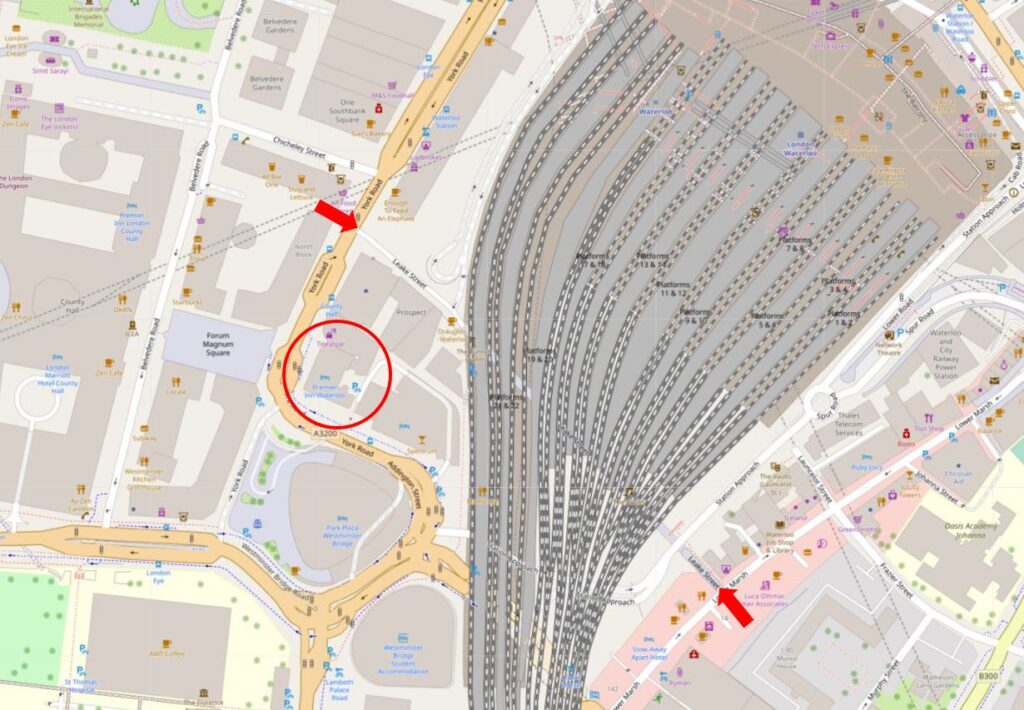

By the time of the 1951 Ordnance Survey Map, the name had changed from York Street to Leake Street, again highlighted by the red arrows in the following map (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’:

The name change was due to early 20th century attempts to reduce the number of duplicate street names across the city, as reported on the 28th September 1920 in the Westminster Gazette: “There are five streets within a radius of 1.5 miles from Piccadilly Circus all named York-street. It has been decided to re-name York-street, Lambeth, Leake-street in honour of Dr John Leake, who was largely instrumental in founding the general lying-in hospital in the street”.

So Dr John Leake finally had his name close to the pioneering hospital that he founded back in 1765. The street can still be found today, although most of the street passes under the tracks of Waterloo Station as shown in the following map, with the red circle showing the location of the old hospital building (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

I went to take a look at the street named after Dr John Leake, and this is where this is a post of two very different halves:

Leake Street

To find Leake Street walk past the hospital, and past the adjacent Premier Inn, then an office block until you find a street heading towards the arches beneath Waterloo Station. Unfortunately there are no street name signs to confirm that this is Leake Street, however this is the current view of the street from York Road:

The first part of the street has a somewhat derelict feel, and this is an indication of what is to come:

The entrance to Leake Street Arches where Leake Street runs underneath Waterloo Station. At least here we can find Leake’s name, although I doubt very much whether many of those who pass this way realise the association of the name and hospital.

Looking down Leake Street Arches:

Almost every available space is covered in graffiti.

This dates back to May 2008 when the artist Banksy, along with 29 other street artists decorated much of the tunnel with graffiti.

Up untill then, Leake Street had been a rather gloomy, disused road. The arches on either side were generally used for storage, including a rather unusual use as an oil company kept core samples retrieved during drilling in a couple of the arches.

The Leake Street Arches are today a bit of an institution, with bars occupying many of the arches that lead off from the main tunnel.

As well as the side walls, the brick roof of the tunnel has been used as a canvas:

A riot of colour:

Graffiti is not static and is continually being refreshed. During my walk through the tunnel a couple of weeks ago, an area of wall had been prepared for a new work, and paint cans were ready on the floor:

New works are not just painted in isolation, they frequently have a film crew ready to record the process.

A glimpse inside one of the side arches that is not in use shows the size of the space and the wonderful brick work that makes up the arches and tunnel that support the station platforms and tracks above:

Almost every surface has been painted:

Graffiti changes regularly and is actively encouraged throughout the tunnels of Leake Street.

Walls, ceiling and occasional parts of the floor are covered in graffiti:

At the far end, there are steps up to Station Approach Road which runs alongside Waterloo Station, or follow the walkway on the left, under Station Approach to get to Lower Marsh. The road curves to the right as shown in the following photo to a fenced off dead end.

Looking back along Leake Street Arches:

Apart from the sign for Leake Street Arches at the entrance to the tunnel, there is no further mention of the name, and no reference as to the source of the name. The web site for the tunnel and arches. Leake Street Arches, makes no reference to the source of the name, focusing instead on the cultural, entertainment, food and drink venues within the tunnel.

I have no idea what Dr John Leake would have thought if he could see the only place on the South Bank where his name can be seen. What would be good is if Premier Inn could add a plague to the building.

As well as the tunnel and arches, I am sure Dr John Leake would be fascinated by how much the care of women during pregnancy and childbirth has developed, how the mortality rate for mothers and babies has reduced to levels perhaps unimaginable during the mid 18th century, and that care is now available to all via the NHS without any need for subscribers recommendations.

As well as old newspapers, I have used a fascinating book to research this post. In 1977 Professor Philip Rhodes published “Dr John Leake’s Hospital”. Just under 400 pages of detailed history of the hospital, Leake, social conditions across London and attitudes to pregnancy and child birth, as well as the development of this specialised area of care.

Professor Philip Rhodes was on the consultant obstetric staff at the General Lying-In Hospital, eventually becoming Dean of the Medical School and Governor of St Thomas’s Hospital.

His book is a fascinating history of an aspect of London life, and an institution where over 150,000 people where born from 1767 to 1971 – all thanks to Dr John Leake.