If you take a walk around London, you cannot miss the numbers of building sites and cranes that seem to be transforming the city on a daily basis.

The majority of new buildings are typically carbon copies of buildings that could be in any world city. Built of the same materials and providing occupation space for a transient work force or absentee owners.

I love buildings that have a reason to be where they are, they have a history to tell. They are not competing for height or shape and they could not be anywhere else apart from London.

A few months ago I featured one such building, the Faraday Building in Queen Victoria Street and this week I want to highlight a second building that can be so easily missed, and dismissed as another office block of pre-war construction, but look a bit closer and it has a fascinating history to tell.

I was walking along Millbank, alongside a building I have walked past many times and which I have never really stood back and studied, but this time I happened to look up at the roof line. It probably helped being winter as the trees were bare.

I found myself staring at another man who spends his time looking down at Millbank:

He is such an unusual figure. Not the usual candidate for a London statue who usually tend to be royalty, military leaders, those who played a key role in the history of the country or development of London. This character is anonymous, but is clearly a working man, shirt sleeves rolled up, strong and very industrial.

This is the old Imperial Chemical Industries head office building, Imperial Chemicals House at 9 Millbank, as seen below from the end of Lambeth Bridge. If you glanced at the build it would be very easy to miss the detail, however the building provides a lesson in industrial history and the history of chemistry.

The building was designed by Sir Frank Baines FRIBA and was constructed between 1929 and 1931. He was also employed by the Office of Works at the same time as his work on Imperial Chemicals House. This caused a stir in parliament as this was significant private work and there was concern that this would impact his work for the Office of Works. Sir Frank could not end his obligations to the construction on Millbank so he retired from service in the Office of Works.

The man in my first photo is one of a series of statues along the building at the base of the doric columns. He is the first statue coming from the direction of Parliament Square, at the far right of the above photo.

Further along we find the following statue. Note the incredible detail on these statues.

These statues are by Charles Sargeant Jagger, a British sculptor and they represent the industries of Chemistry, Agriculture, Marine Transport and Construction.

Charles Sargeant Jagger lived between 1885 and 1934 and after active service in the First World War was responsible for a number of well-known war memorials. His war memorial work in London includes the Great Western Railways war memorial at Paddington Station and the Royal Artillery memorial at Hyde Park Corner.

He was well-known for the rugged and realistic style of his work, which clearly comes across in the statues on the ICI building.

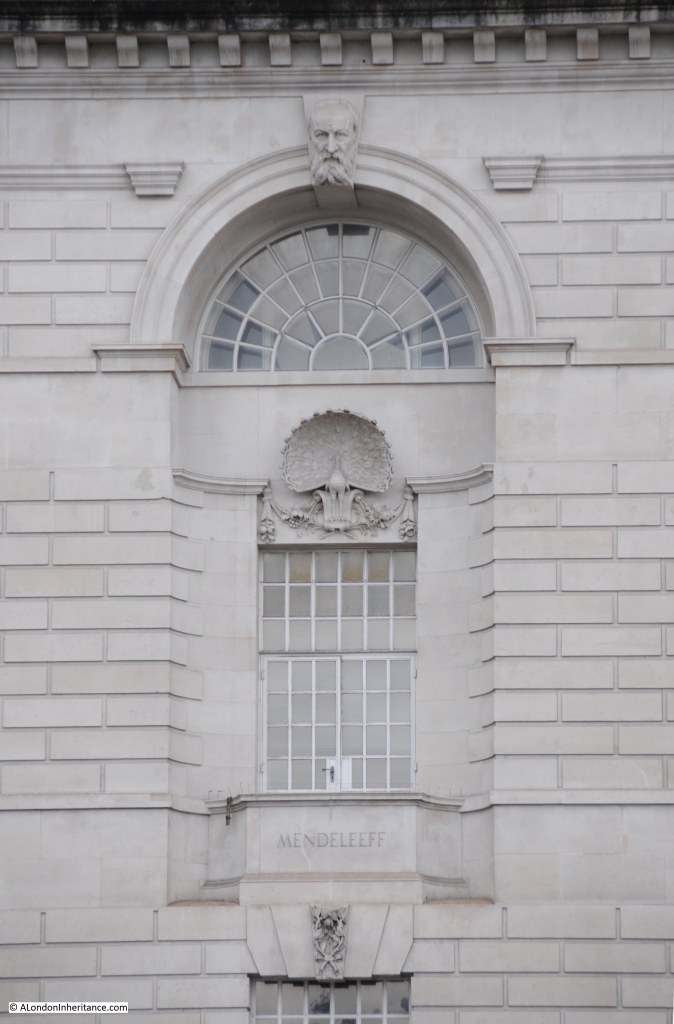

Now look below the 5th floor balustrade and there are a series of large windows, each with a carving of a head on the key stone at the top of the window with a name on the balcony below. This provides us with a lesson in both industrial history and chemistry.

Imperial Chemical Industries, or ICI was once one of Britain’s largest industrial companies. ICI employed tens of thousands of people, had a global reach and was active across all the major areas of chemical manufacturing along with an extensive pharmaceutical business, however like so much of British industry, ICI lost its way towards the end of the 20th century, sold off the pharmaceutical business (now AstraZeneca) and ended up being purchased in 2008 by the Dutch chemicals manufacturing business AkzoNobel.

ICI was founded in 1926 by the merger of four chemical companies, Nobel Explosives, United Alkali Company, British Dyestuffs Corporation and Brunner, Mond and Company, and it is to this last company that we find our first name:

Ludwig Mond was born in Germany in 1839 and was active in a range of chemicals businesses, forming his own company, Brunner Mond, along with the industrialist John Brunner to manufacture soda at a factory at Northwich. He also developed a process for the production of pure nickel, building a factory in south Wales to develop this side of the business.

His son was Alfred Mond, the subject of the next window:

Alfred became the managing director of Brunner Mond and it was Alfred who was instrumental in the formation of ICI and became the first chairman of the new company.

The sculptor for the heads along the top of these windows was William Bateman Fagan, a Londoner born in Bermondsey in 1881.

The next key figure in the formation of ICI was Harry McGowan:

Harry McGowan started work as an office boy at the age of 15 at the Nobel Explosives Company (founded in 1870 by the chemist Alfred Nobel, who was to use part of his estate to establish the Nobel Prize).

McGowan worked he way to the top of Nobel Explosives to become Chairman and Managing Director when Nobel was one of the four companies to merge to form ICI.

He became the second Chairman and Managing Director of ICI after Alfred Mond.

Now we come to the scientists who discovered the processes and the key elements that were the foundations of ICI’s business.

The first is Liebig, or Justus von Liebig to give him his full name, a German chemist who lived from 1803 to 1873. Liebig’s work in the field of organic chemistry and the application of chemistry to agriculture were significant. It was Liebig who discovered that the element Nitrogen was a critical nutrient for plants, and therefore a key component in the production of agricultural fertilisers.

Apart from the ICI building, Liebig has another prominent connection with London. His work in agriculture and foods resulted in his development of a process for the manufacture of beef extracts. To commercialise this process he founded the Liebig Extract of Meat Company which went on to produce Oxo, and in London built a factory where the Oxo Tower stands to this day on the southbank of the Thames.

Next we come to Joseph Priestley, an English theologian and scientist (or more correctly for the time a natural philosopher) who lived from 1733 to 1804. It was Priestley who discovered Oxygen, however his insistence in continuing to support an earlier theory that attempted to explain how fires burnt in air by the release of material called phlogiston and that fires stopped burning when the air around them could not absorb any more phlogiston, left him somewhat isolated.

Priestly also had controversial religious views for the time, being a religious Dissenter and along with Theophilus Lindsey founded Unitarianism with the first Unitarian service being held in the Essex Street Chapel, located just off the Strand. A fascinating man at a key moment in history at the early stages of the industrial revolution.

Next is the Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite and the founder of Nobel Industries Limited, one of the four companies that merged to form ICI.

Nobel’s lasting legacy is the Nobel prize for which he donated the majority of his estate having been concerned how history would remember him as the inventor of explosives.

Lavoisier was a French chemist born in 1743 and was executed in 1794 by guillotine during the French revolution, a victim of the anti-intellectual atmosphere of the revolution and of anyone connected with authority prior to the revolution.

Fortunately his work survived and he was key in understanding the processes of combustion and proving that water was not an element, but made from Oxygen and Hydrogen. His work help to disprove the phlogiston theory which Priestly was desperately trying to support.

Finally we come to Mendeleeff or Dmitri Mendeleev, the Russian chemist who lived from 1834 to 1907. His work on the composition of petroleum was key in understanding how oil and petroleum could be used as a feedstock for the chemicals industry, processes on which so much of ICI’s business would depend.

He was also the inventor of the Periodic Table of Elements, the table that classified the ordering of elements according to their key properties. The table not only helped understand elements but also provided a structure to classify future discoveries and to identify where unknown elements must exist to populate the gaps in the table.

ICI’s initials are ornately carved on many plaques across the building:

One of the side doors to the building, again with the ICI initials and the start of construction date of 1928:

The main entrance on Millbank. Whilst the carved heads may not be very obvious, the main entrance provides a very dramatic entry to he building. It is again the work of William Bateman Fagan. On the door, the carved panels show the development of science and technology. The panels on the left show stone age technologies and show the construction of a basic tented home starting with building the frame onwards to completion. The final panel includes the completed tent with Stonehenge being seen in the background. The panels on the right hand door show contrasting modern industrial scenes. Just inside the door can be seen Britannia along with a busy shipping scene.

Although the name ICI is gradually fading into history, Imperial Chemicals House, or 9 Millbank as it is now more simply known demonstrates a 1920s confidence in science, technology and industry, not so evident in the country 90 years later, and I doubt we will see again this type of building that so proudly displays the heritage of the buildings creation.

Although the name ICI is gradually fading into history, Imperial Chemicals House, or 9 Millbank as it is now more simply known demonstrates a 1920s confidence in science, technology and industry, not so evident in the country 90 years later, and I doubt we will see again this type of building that so proudly displays the heritage of the buildings creation.

So if you walk along Millbank, take some time to discover the work of Charles Sargeant Jagger and William Bateman Fagan.

There are many good books that explore the scientists, chemists and industries highlighted on Imperial Chemicals House.

The Lunar Men by Jenny Uglow documents the chemists, inventors and natural philosophers associated with the Lunar Society between 1730 and 1810 and includes Priestley and Lavoisier.

The Slow Death of British Industry by Nicholas Comfort is an excellent account (although very depressing) of the death of much of British industry between 1952 and 2012 including ICI.