I have always been fascinated by London’s place in the wider country. One aspect of this has been London as a destination for journeys over the centuries, which in the past has been driven by London’s role as a centre of royal, political, judicial, religious and commercial power. One such journey was in the 13th century, when the body of Queen Eleanor of Castile was brought from the place of her death near Lincoln, for burial in Westminster Abbey.

This was a long journey, and where the procession with Eleanor’s body stopped for the night, a cross would later be built to commemorate the journey, the Queen and provide a focal point for prayers for the Queen.

I have long wanted to follow the route, to find the remaining crosses, and the sites where they are missing, so this summer, we traveled the route, starting at Harby, the location of Eleanor’s death, through to Westminster Abbey.

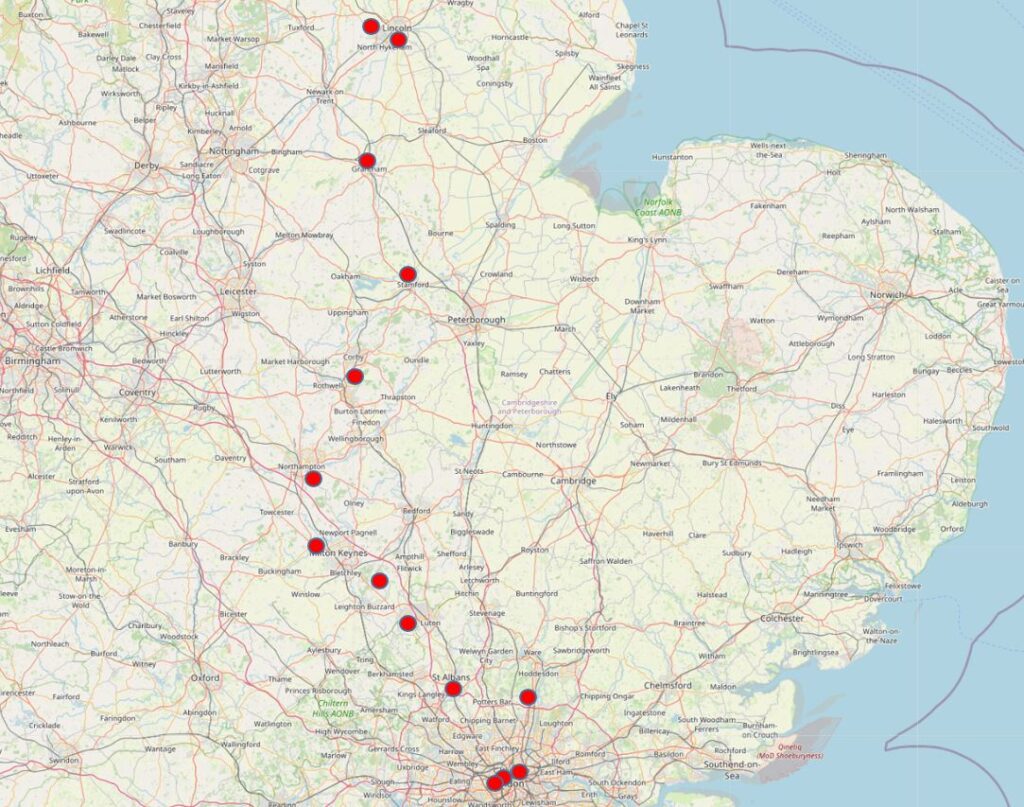

Starting today, and with some additional posts during the coming week, join me on a trip across the country, from a small village in Nottinghamshire to a tomb in St Edward the Confessor’s chapel at Westminster Abbey, with the stopping points identified in the following map (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

The first red dot is at Harby, Nottinghamshire, then Lincoln, Grantham, Stamford, Geddington, Hardingstone, Stony Stratford, Woburn, Dunstable, St. Albans, Waltham and then into Central London at Cheapside, Charing Cross and finally Westminster Abbey.

Today’s post covers the first two red dots, Harby and Lincoln.

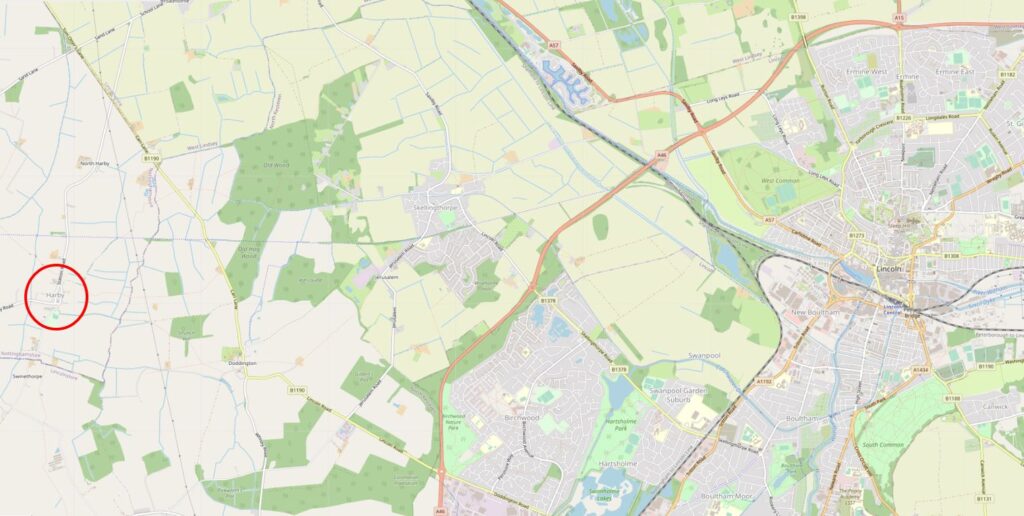

Harby is a very small village, which although being very close to Lincoln, is on the edge of the county of Nottinghamshire. Harby is ringed on the left of the following map, showing a small village in a very rural location. Lincoln is the city on the right:

Arriving at the village of Harby, and the name sign at the entrance to the village includes a plaque to Queen Eleanor:

So who was Queen Eleanor of Castile, and how did she end up in the small village of Harby?

Eleanor of Castile was a remarkable woman.

Born in 1241 in Burgos, Spain, Eleanor was the daughter of Ferdinand III of Castile and Joan, Countess of Ponthieu.

Ferdinand III was responsible for the considerable expansion of Castile as he took back much of the south of what is now Spain that had been taken by the Almohad Caliphate, who had originally come from north Africa where they ruled extensive lands.

Ferdinand III took back the area then known as Al-Andalus, and the current name Andalusia is derived from the earlier Arabic name.

During Eleanor’s early life, her father Ferdinand was away for considerable periods of time, however he was responsible for ensuring his children’s education, and unusually for a royal daughter of the time, Eleanor was highly educated.

When not on military campaigns, Ferdinand and Joan would travel across Castile and Andalusia, and their children would often come with them along with the royal court. It is from her upbringing that Eleanor probably saw the role of a Queen as being expected to accompany the King and royal court on their travels, and she did travel with Edward I on his campaigns and journeys across his British kingdom, and abroad.

Ferdinand III died in Seville in 1252, and Eleanor’s half-brother, Alfonso X took over the Castilian crown.

As was standard in medieval royal families, children were often seen as important in establishing relationships through marriage with other royal families, with the settling and prevention of disputes, and to bring key European areas of land under the control of a royal family looking to expand their power.

This is what Eleanor would have been brought up to expect, and what did indeed end up happening, although unlike many royal marriages, Eleanor’s appeared to have been a very happy one, with Edward and Eleanor being devoted to each other.

The marriage that Alfonso arranged for Eleanor was based on rival claims for the Duchy of Gascony, part of Aquitaine in southern France, which was part of the Angevin Empire and ruled over by English kings through the House of Plantagenet. Europe at the time was a complex web of kingdoms and families, most of which also were part of a complex web of family relationships.

The marriage arranged by Alfonso X of Castile and Henry III of England resulted in the marriage of thirteen year old Eleanor with Henry’s son Edward, then aged fifteen and put together a relationship between the two royal families that would avoid a potential Castellan attack on Gascony.

They were married in the Abbey of Santa María la Real de Las Huelgas in the city of Burgos, after which they spent a year in Gascony, with Eleanor then travelling to England, followed soon after by Edward. One wonders what a fourteen year old must have felt travelling to a new country, on her own, and without any supporting family members, although she must have had some members of Edward’s court with her.

The following image from an early fourteenth-century manuscript shows Edward and Eleanor, Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edward_I_and_Eleanor.jpg Attribution: Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

I will cover more about Eleanor’s life as queen in the coming posts, but for now I will jump forward to the time of her death.

Prior to her death she had been in Gascony, and it seems she may have contracted a form of malaria whilst there. Following her return to England, along with Edward, she started a tour of the north with the intention of visiting many of the properties that Eleanor owned.

She was heading towards Lincoln, but became too unwell to continue travelling, and stopped at the house of Richard de Weston in the village of Harby, and it was here that she died on the 28th of November 1290.

Although an Eleanor Cross was not erected in Harby, as the place of her death, the village seemed the appropriate place to start if I was to follow her route back to Westminster Abbey.

Harby is a small village in the flat, agricultural lands to the west of Lincoln. Although very close to Lincoln, it is in the county of Nottinghamshire, not far from the border.

in the 2011 census, the village had a population of 336, and the village dates back to at least 1086, when Harby was mentioned in the Doomsday book. The Primary School in Harby is named after Queen Eleanor.

Very little has happened in Harby. Apart from the death of Eleanor of Castile, and more recently, the crash of an RAF Meteor jet into the centre of the village, killing the pilot, one person on the ground, injuring a number of others, and destroying some houses.

The site of the house of Richard de Weston is close to Harby church. The current church is not that old, having been built between 1874 and 1877. It has a rather impressive side tower and spire for a relatively small village church.

Eleanor of Castile features prominently at the base of the tower:

The arms on the left are the three lions of the Royal Arms of England. It is interesting that the origins are these arms date back to the Plantagenet’s, a royal family who had their origins in Anjou, France.

The arms on either side of the statue are those of Eleanor of Castile (the arms of Leon and Castile). To the right are the arms of Ponthieu (Eleanor’s mother was Joan, Countess of Ponthieu and Eleanor became Countess of Ponthieu in her own right in 1279 following her mother’s death). We will see these arms many times on the journey to London.

Path and lamppost in Harby churchyard heading to the rear of the church:

The moated house of Richard de Weston where Eleanor of Castile died is just to the west of Harby church, and the following view is to the west from the edge of the churchyard. An outline of the site is apparently still visible, believed to be the area surrounded by the small trees / bushes:

In the hours following Eleanor’s death, Edward must have been at a complete loss. She had died at the age of 49, and should have expected a longer life despite the early mortality of the age. Her mother was still alive and Edward was probably expecting to spend more years with his wife. They had been married for 36 years.

Edward finally agreed to leave Harby, and a procession headed towards Lincoln, where the start of Eleanor’s last journey to London would begin, so Lincoln was my next stop.

The procession headed to St Katherine’s Priory which was to the south of Lincoln, just outside the City walls.

The priory was part of the Gilbertine Order, founded in the 12th century by a local Lincolnshire saint, St. Gilbert. On the arrival of the body of Eleanor, the monks had the task of removing many of the internal organs and then embalming the body of Eleanor, ready for the long journey to London. Her heart was placed in a box, and remaining internal organs in another box.

Eleanor’s coffin was then carried in procession up the steep hills through the centre of Lincoln that lead to Lincoln Cathedral.

We had stayed in Lincoln overnight, and getting up early had the benefit of walking the quiet streets of Lincoln up to the cathedral, before the shops and cafes opened, and lots of other people followed the same route.

The route from lower Lincoln up to the cathedral is via the High Street, the Strait, and then along the appropriately named Steep Hill.

Glimpses of the cathedral in the distance:

Eleanor’s body was taken along these streets twice. Firstly from priory to the cathedral, then leaving the cathedral on the start of the journey to London.

Remarkably there is a house still standing that would have seen Eleanor’s body pass by. This is Jews House on the Strait:

Jews House is believed to have been built between 1150 and 1160, so was already over 100 years old by the time of Eleanor’s death. Lincoln had a thriving Jewish community in the 11th and 12th centuries, and as Christians were not allowed to be moneylenders, Jews were known, and resented for holding this occupation.

1290, the same year as Eleanor’s death, was the year that the Jews were expelled from England, as Edward I had issued the Edict of Expulsion on the 18th of July 1290 requiring all Jews to be expelled from the country by All Saints Day (1st November).

This was the culmination of years of anti-Semitic attacks and persecution by both the population and the state.

Houses owned by the Jews were seized by the Crown at the time of expulsion, so Edward I may have been the owner of Jews House at the time of Eleanor’s death.

Continuing up Steep Hill, with Well Lane (and water pump) to the right:

Almost at the top:

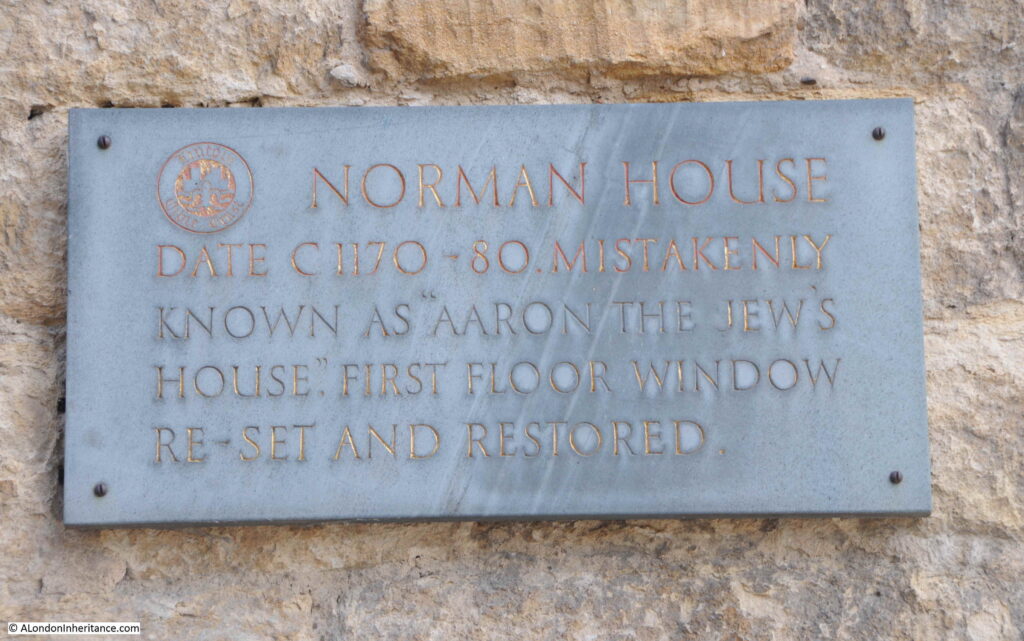

There are two 12th century buildings on the streets leading up to Lincoln Cathedral. The first is Jews House, and the second is Norman House:

This house would also have seen Eleanor’s body pass. as it was built between 1170 and 1180, however the plaque on the wall to the right reveals some confusion between the two 12th century houses:

The plaque explains that Norman House is mistakenly known as “Aaron the Jew’s House”, and this confusion appears to extend to English Heritage, who have a photo of the building, but with the following text (see this link):

“This is probably the best known Norman house in England. It had a first-floor hall with shops below. It was built in 1170-80. It is particularly important as an example of 12th century domestic architecture. The house is also known as The Jew’s house. 900 years ago the Jews were able to work as money lenders and Christians were not. This led to discrimination and persecution. A period known as the Jewish Expulsion in 1290 resulted in violence against and murder of Jewish people including the female owner of the Jews House who was executed.”

Wikipedia’s entry on Aaron the Jew also states that Norman House “is sometimes associated with Aaron of Lincoln”.

I am going with the plaque on the house, as the other house I photographed earlier does have the name Jew’s House on a large name sign on the wall.

Further along the street is a much later house with another plaque:

The plaque records that the soldier and author T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) lived in the house in 1925. It is now Browns Restaurant and Pie Shop.

At the top of Steep Hill, and at the highest point in Lincoln is an open space, and at either side of this space are the two symbols of medieval power. The cathedral:

And Lincoln Castle:

Lincoln Castle was my first destination. An Eleanor cross had been built by Richard of Stowe in the vicinity of St Katherine’s Priory, however it had been destroyed during the dissolution of the monasteries in the mid 16th century. The land and buildings of the priory were taken by the crown, and the site would later become the location of a Wesleyan chapel and then a parish church. The church closed in the 1970s and the building is now used as an events space.

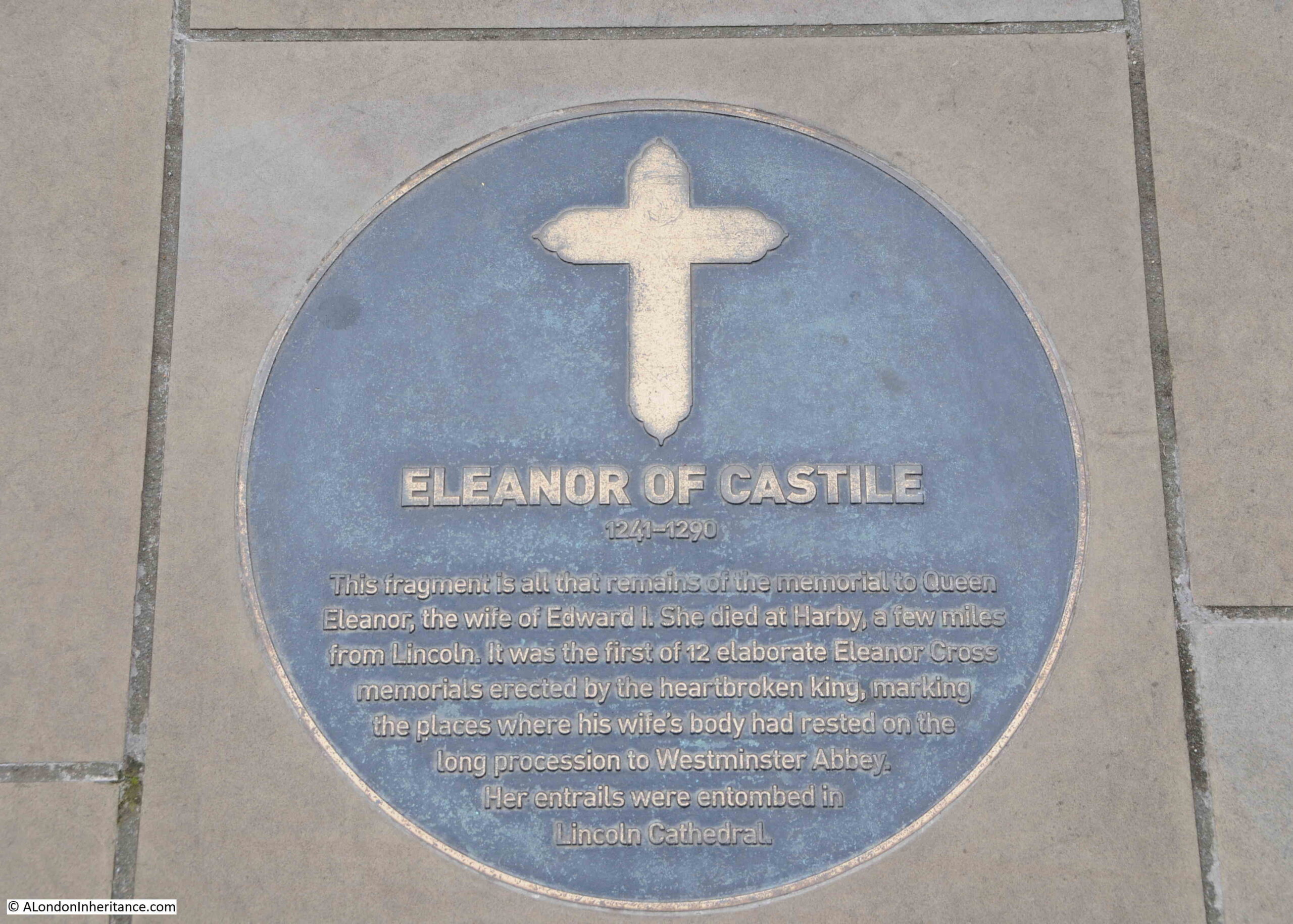

Although what was the first Eleanor cross on the route to London had been destroyed in the 16th century, a small part has survived and can be seen in the grounds of Lincoln castle, and finding this was my aim in visiting the castle.

The surviving part of the Lincoln Eleanor cross, which has the folds of Eleanor’s dress visible:

A plaque on the ground confirms that this is part of the cross, and also confirms that her entrails, which were removed at St Katherine’s Priory, were entombed in Lincoln Cathedral:

The cathedral would be my next stop, however time for a look around the magnificent Lincoln Castle.

The castle dates back to 1068, when the Normans constructed a motte and bailey castle (earthen mound topped with wooden defensive walls). This would soon be replaced by a larger stone built castle.

This was an important location, on high ground, commanding the town of Lincoln, and with impressive views over the surrounding countryside. It was meant to be a statement that the Normans were now in charge, and to also act as a base from which to subdue the rebellious northern parts of the country.

The castle has been involved in many military actions during the medieval period, and came under siege a number of times. The last was during the English Civil War, when in 1644 the occupying Royalist force was under siege from Parliamentary forces, who eventually captured the castle.

The castle occupies a large space. Much of the central space is now open and covered in grass. There are a fine set of walls around the perimeter with a walkway along the top. There are a number of interesting artifacts scattered around.

One of these artifacts has a London connection.

The heathland to the south of Lincoln was considered a treacherous and dangerous place to be after dark, in the days before decent roads and street lighting.

In 1751 Sir Francis Dashwood commisioned what was a land based lighthouse to be built to provide some reassurance to travellers. Standing 92 feet tall, the lighthouse had a lantern at the top, which would be lit after dark.

The lantern was destroyed by a storm in 1808, and was replaced by a statue of King George III. The bust was made by the Coade stone company, run by Eleanor Coade, who was based in London.

As far as I know, Coade stone was only made in London, with the main factory being on the Southbank, just to the west of the Royal Festival Hall.

The lighthouse was reduced in size by about 40 feet during the early years of the Second World War. The flat land of Lincolnshire was the site for a number of RAF bases, and the height of the lighthouse was considered a risk to aircraft.

The bust of King George III was saved, and this Coade stone bust, probably made on the Southbank of the Thames in London, is now on display in Lincoln Castle:

Within Lincoln castle is a brick built, Victorian Prison. The view of the front of the prison:

And the more austere rear view of the prison:

The prison was in use between 1848 and 1878, and you could have been imprisioned here for all manner of crimes, from the most trivial all the way up to murder. The prison housed men, women and children and employed a seperation system which the Victorians believed would prevent prisoners becoming corrupted and further criminalised by contact with fellow prisoners.

The most remarkable example of this system which we can see today is in the chapel. Each seat for a prisoner was screened from the prisoners who would have sat either side, and from prisoners in the seats above and below. The system ensured that prisoners could attend a service with other prisoners, but without coming into contact with any of them.

Visiting the prison chapel, you can stand in the pulpit and survey the prisoners in their individual place:

It was rather weird walking into the chapel. You enter from the door at the top of the steps in the above photo, then walk down the steps. You can just see the tops of the heads of the prisoners – for one unsettling moment you are not sure whether or not they are real.

The walk along the top of the walls provides good views over the surrounding town and countryside, including across to the cathedral:

And down into the centre of the castle with the prison on the left and the Lincoln Crown Court building in the centre of the view:

View along the walls:

Courts have been held in the castle ever since it was first built. A castle was the seat of Royal power and was therefore the place where Royal justice would be dispensed.

The current building was completed in 1823 to a design by Sir Robert Smirke. Remarkably, this building in the centre of a castle is still a Crown Court. There have been a number of attempts to move the court out of the castle grounds, however the latest attempt was abandoned in 2020 when Her Majesty’s Courts Service claimed that a moved to new premises would not offer value for money, or any benefits to the public or court users.

Lincoln Crown Court, providing some hundreds of years of continuity of use within the castle grounds:

The Observatory Tower offers fine views over the surrounding countryside:

Including views down into the centre of Lincoln, which is why the Normans originally built the castle on this high point.

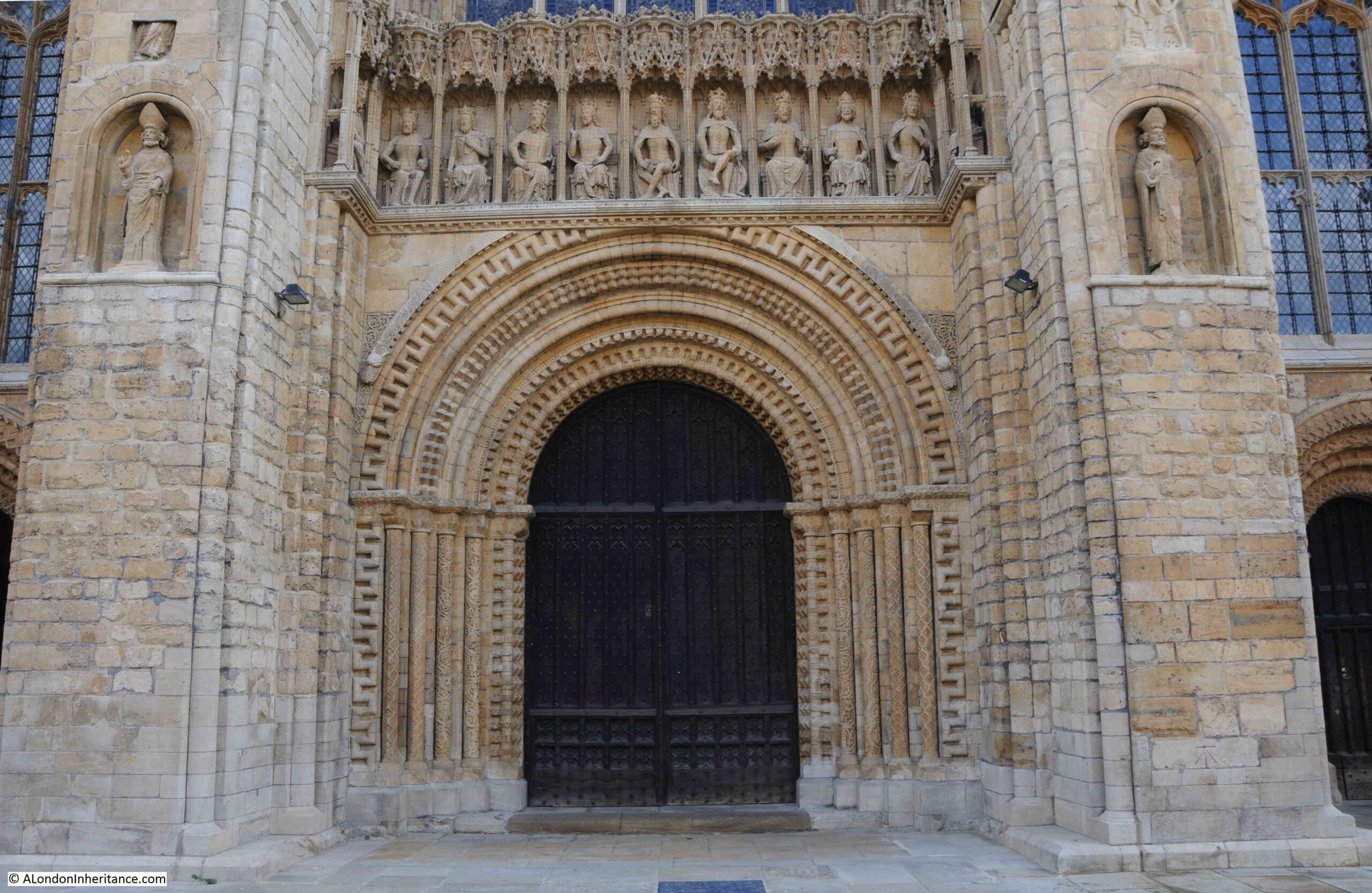

After a visit to the castle, my next stop was the cathedral, to find Eleanor’s tomb:

The above photo is of the western front of the cathedral. Remarkably the two towers once had wooden spires adding considerable height, and from the 14th century, for two hundred years, Lincoln cathedral was the tallest building in the world. The top of the spires were about 10 feet taller than old St Paul’s Cathedral in London.

The author A. F. Kendrick, who wrote a comprehensive description of the architecture and fabric of the cathedral in 1898 did not think much of this view of the cathedral:

“The West Front is massive and imposing, and possesses some features of considerable interest; beyond this, little can be said for it, as it is architecturally somewhat of a sham.“

His view was that the west front was basically a large screen wall, that obscured the view of the rest of the cathedral, and whilst impressive, once you view it as a screen, you realise what the original architects could have achieved. I suspect this is looking at the building with a 19th century view, many hundreds of years after construction.

The origins of Lincoln Cathedral, as with the castle, date back to the Norman Conquest, after which William the Conqueror gave the land to a Benedictine monk by the name of Remegius. He had been a supporter of William during the conquest, and this was his reward, although he then had the task of constructing the cathedral.

Work started in 1071, and twenty years later the cathedral was consecrated.

The cathedral suffered a fire and an earthquake in the 12th century, and then Hugh of Avalon (his birthplace in France) was appointed as Bishop of Lincoln in 1186.

He commenced a rebuilding project in 1192, and it is substantially this cathedral that we see today.

Lincoln cathedral is a magnificent building, but I wanted to see Eleanor’s tomb. Not where her body was laid to rest, rather where her entrails that had been removed at St Katherine’s Priory were buried. The monks at the priory also served in an adjacent hospital, and it is probably because of this that they had the skills needed to prepare and embalm Eleanor’s body.

And it was here that I had a problem with my camera. I dropped it a while ago, and dented the lens. Since then the anti-vibration and focus functions sometimes play up, particuarly in low light, and this happened when I photographed the tomb, resulting in a couple of unusable photos, one of which was Eleanor’s tomb.

A lesson in checking photos after taking, but thankfully I found a good photo on the Geograph site which allows reproduction under a Creative Commons License, so here, thanks to Richard Croft is a photo of Queen Eleanor’s tomb in Lincoln Cathedral:

Queen Eleanor’s tomb cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Richard Croft – geograph.org.uk/p/241010

The tomb is rather impressive given that it contained only some of her organs. As with the church in Harby, the side of the tomb has the Royal arms of England on either side, the arms of Ponthieu and those of Queen Eleanor of Castile in the middle.

Following the interment of her organs, which presumably was accompanied by a religious service, Eleanor’s body was then taken out of the cathedral, and the long journey to London began.

The architecture and scale of Lincoln Cathedral is a fitting place for the first of her tombs.

The exterior of the cathedral is impressive enough, however internally the cathedral is magnificent, with some wonderful carved stone decoration:

The cathedral treasury contains a collection of valuable objects. The majority of these have been assembled over the last few hundred years as many of the cathedral’s valuable artifacts including gold, silver and books were taken by the Crown during the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII. View through the entrance to the treasury:

A number of the objects in the treasury have been found during archeological excavations in the cathedral, including a couple of silver chalice, one of each were recovered from two tombs of 13th century bishops of Lincoln who were buried in the cathedral.

View of the Choir, looking to the west:

The following photo is looking towards the Father Willis Organ which stands proud above the choir screen

The Chapter House at Lincoln Cathedral is one of the earliest of the polygonal chapter-houses in England. Construction was started in 1219, and employed a large central pillar as at the time architectural and building methods had not yet devised a method to support the whole roof from the side walls.

Surrounding the Chapter House are alcoves built into the lower part of the side wall, each one being a seat for use when meetings and other ceremonies were held in the room. One of which was the Parliament of 1301 which met in Lincoln.

Petitions were heard at the Lincoln Parliament for restoration of the city’s liberties which had been taken away in 1290 by Edward I due to issues with corruption and poor management within the city, that had caused a violent response within the city.

The internal roof of the Chapter House, which has been restored since being built in the early 13th century.

There was much more to see in both the Castle, the Cathedral and throughout Lincoln, however we had eleven more places to find where a cross had been erected to commemorate one of the places where the procession carrying Eleanor’s body stopped for the night, on their way to Westminster Abbey.

We left the cathedral and headed back down Steep Hill, following the assumed route of the procession as it left the cathedral back in 1290, although we had an early stop off at a Steep Hill cafe.

I will continue the journey in posts during the coming week, and also learn more about Eleanor of Castile, Edward I and England during the reign of Edward I.