Turn south from Holborn, or east from Kingsway, away from these busy streets, and through some side streets you will find Lincoln’s Inn Fields:

Lincoln’s Inn Fields is a wonderful open space, and was looking good during my visit on a sunny spring day. Immediately to the west of Lincoln’s Inn, after which the space takes its name, it has been an open space for a considerable time.

View looking to the east with the buildings of Lincoln’s Inn on the eastern border:

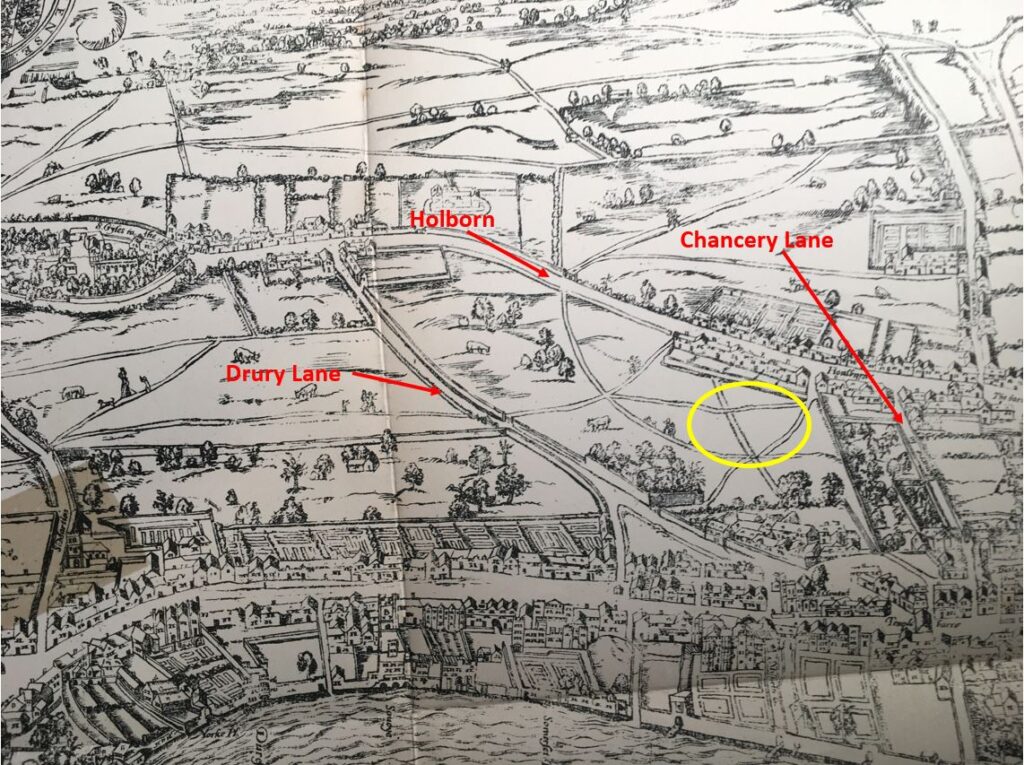

In the 1561 Agas map of London, the area now occupied by Lincoln’s Inn Fields was still open space. Although it is very difficult to be precise about the location on the Agas map, due to the accuracy of the map, perspective and scale, it is possible to roughly locate the position by comparing with other streets, which I have marked in the following extract with the yellow oval showing the very rough location of what would become Lincoln’s Inn Fields:

The map shows footpaths across the fields, limited building to the north along Holborn, and the building and gardens that then lined the length of the Strand.

The fields were named Cup Field and Purse Field and at the time of the Agas map, they were pasture lands owned by the Crown.

Lincoln’s Inn were concerned about the growth of the city around their buildings and objected to any building on the two fields. In the 1630s, the fields were sold to William Newton of Bedfordshire. He managed to reach an agreement to start the building of houses with Lincoln’s Inn and also secured a royal licence to develop the land.

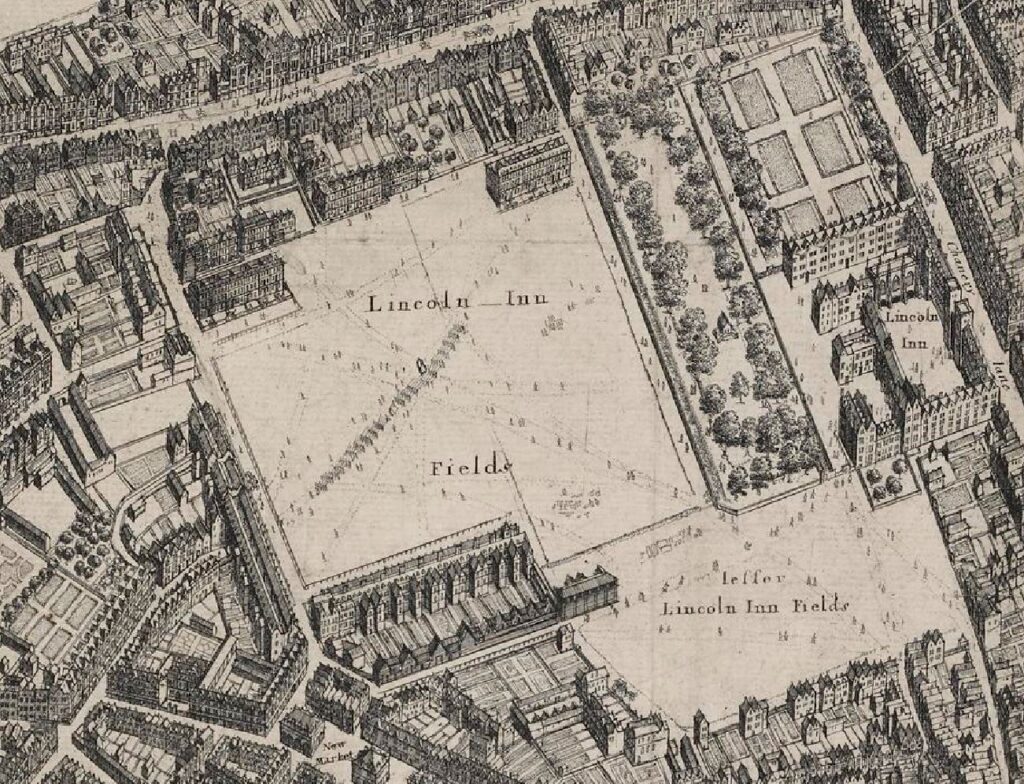

These agreements included leaving the area that is now Lincoln’s Inn Fields as an open space, to the west of Lincoln’s Inn, and by 1660, Lincoln’s Inn Fields was in existence as an open space, and was surrounded by buildings on three sides:

The map shows that on the north and south sides of the Fields, the streets had not been fully completed with housing lining just part of the boundary.

The map also shows that in 1660 there was an area of open space at the south east corner called Little Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

The west side of the space had started to be developed in 1638, and development of the north and south sides started in 1657 when Sir William Cowper, James Cowper and Robert Henley purchased Cup Field. This was just three years before the date of the above map, which explains the partial development of the north and south sides of the fields.

The new owners also had the open space leveled, grassed over, trees planted, and gravel walks laid out. Again, the outline of these can be seen in the 1660 map, and the design was apparently the work of Inigo Jones.

Although the intention must have been to create a pleasant open space for the owners of the new houses along the edge of the fields, in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Lincoln’s Inn Fields did suffer from crime and much anti-social behaviour.

For example, from the Kentish Weekly Post on the 23rd of February 1732: “At night, one Mr. Henshaw, of Gray’s Inn, returning home over Lincoln’s Inn Fields, was attacked by two Street Robbers, who took from him 3 Guineas and a Half, 4 Shillings in Silver, and a Gold Headed Cane; a Light appearing at a Distance, they made off and he had the Fortune to save his Gold Watch.”

The comment about the light appearing at a distance shows just how dark places such as Lincoln’s Inn Fields must have been, without the level of street and general lighting we have now. There would have been no lights across the field, and any lights from the surrounding houses would have been very dim.

Whilst these crimes must have had a terrible impact on the victim, the sentences on those who carried out the crime were often very severe, as indicated by this report from 1733: “George Richardson, John Smithson and Laurence Grace, who were executed at Tyburn on Saturday last, for robbing a Gentleman in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, of his Hat, Wig, and Half a Guineas.”

The same newspaper report also stated that in the same sessions at the Old Bailey which had condemned the three from Lincoln’s Inn Fields, Francis Corcher received the death sentence for robbing an Agate Snuff-Box set in Gold, and of a separate robbery of a Gold Watch and 5 shillings in Hyde Park.

The fields were known as “the head-quarters of beggars by day and of robbers at night”, and there were “idle gangs of vagrants” who went by the names of the “Mumpers and Rufflers”.

A number of those convicted of theft were executed in Lincoln’s Inn Fields in the 17th century.

To try and address the level of crime in the fields, in 1734 the residents applied to Parliament for an Act which would allow them to raise a rate on the residents surrounding the fields, and this would be used to enclose the square, provide keys for the residents only, pay for watchman and a “scavenger” who would ensure the fields and surrounding streets were kept clean.

The railings were put up around the square in 1735.

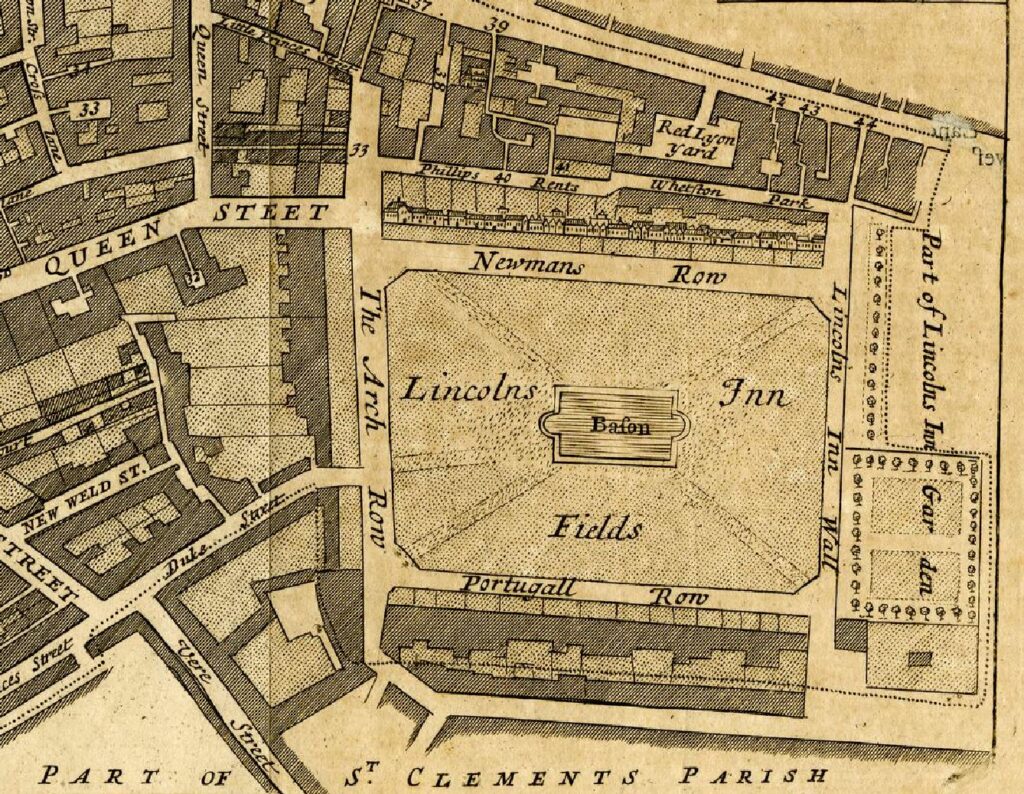

By 1755, development of the north and south sides had been completed, joining the houses along the west of the fields. To the east of the fields, the land was part of Lincoln’s Inn, and the “Little Lincoln’s Inn Fields” shown in the 1660 map had been built over, as shown in the following parish map:

Today, the streets surrounding the central space also go by the name of Lincoln’s Inn Fields, however back in 1766 they had individual names: Newmans Row, The Arch Row, Portugal Row and Lincoln’s Inn Wall.

Newmans Row remains as a short street from the north east corner of the fields up to the alley that leads to High Holborn.

Lincoln’s Inn Wall describes the wall to the east of the street, separating off Lincoln’s Inn.

The Arch Row and Portugal Row also have interesting stories to tell about their naming, but I will leave these to a future post, as I run out of time within the constraints of a weekly post.

The following map shows the area today, with Holborn to the north, Kingsway to the west and Lincoln’s Inn to the east (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

Walking from the south, into Lincoln’s Inn Fields, and there is a shelter in the centre of the space:

In the middle of the shelter, there is a plaque on the floor, recording that “Near this spot was beheaded William Lord Russell a lover of Constitutional Liberty 21 July AD 1683”:

Surprising that such an execution took place in Lincoln’s Inn fields, however I have read that in central London, you are never further than around 500 yards from a place of execution. It would be interesting to test this out.

Who was William Lord Russell and why was he executed?

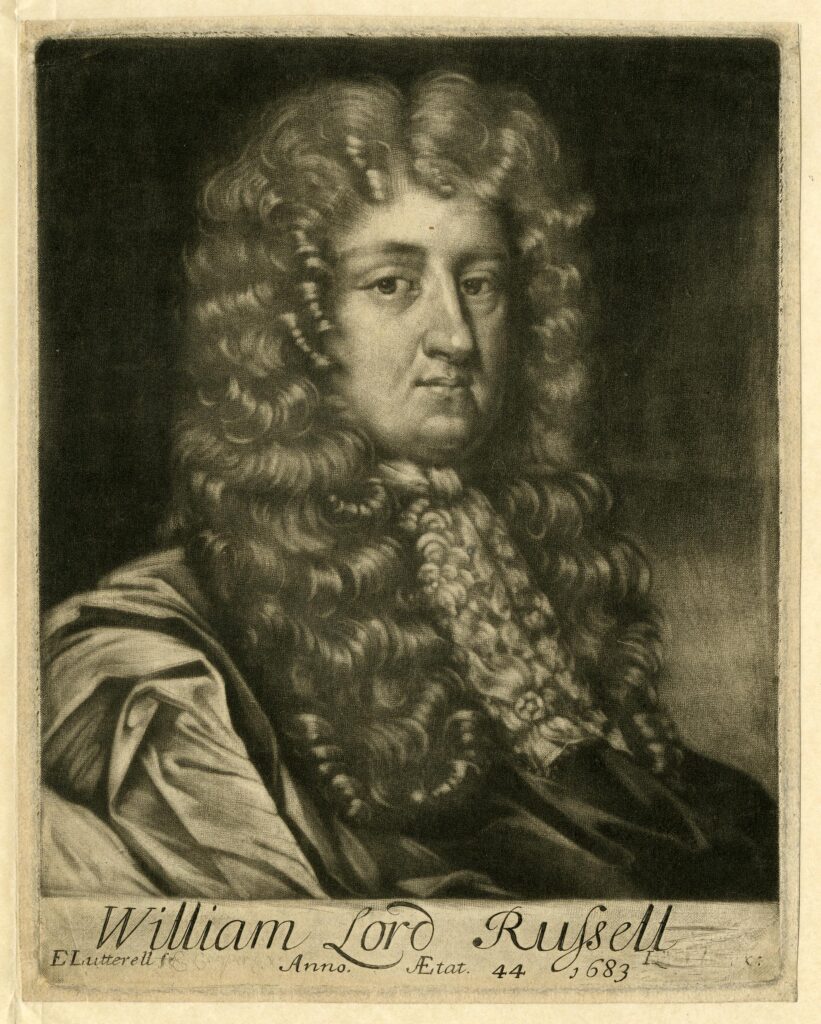

He was born on the 29th of September 1639 as the second son of Sir William Russell, the 5th Earl of Bedford.

He became an MP after standing for the family borough of Tavistock at the general election of 1660. His Parliamentary records state that he was a rather inactive member, only being a member of two committees, one looking at the drainage of the fens, and the other looking at turning the Covent Garden precinct into a parish. He would have had an interest in Covent Garden as his father owned much of the land.

Although he was member for Tavistock, apparently he never visited the town.

William Lord Russell was a Whig – a political party / faction that opposed the principle of absolute monarchy and of Catholic emancipation. Whigs were supporters of the primacy of Parliament.

His work in Parliament did increase, with more activity within various committees and debates, and he also became the member for both Bedfordshire and Hampshire. Even with the election standards of the time, it was rare for a member of Parliament to represent two counties, and he eventually settled for just Bedfordshire.

William Lord Russell (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

It was his views on Catholicism and the Crown that would lead to his death sentence.

Charles II was on the throne, however on his death it was expected that James, the second surviving son of Charles I would become King.

James was a Catholic, and a grouping within the Whigs were strongly opposed that a Catholic could become King, and that as James had a son, it would be the start of a Catholic line of monarchs.

This opposition by the Whigs led to the Rye House plot, which was a plot to murder Charles II and his brother James, Duke of York when they returned from Newmarket to London in March 1683.

The name of the plot comes from the building in which some of the plotters met, and where the King was expected to pass at the time of the attempted assassination. Rye House was near Hoddesdon in Hertfordshire. Following the assassination, an uprising in London was planned.

There was very flimsy evidence as to the seriousness of the plot, who was involved, and whether it would have succeeded. Apparently Charles II returned to London earlier than planned which was the story put about to explain the failure of the plot.

Despite limited evidence and whether or not the plotters would have gone through with their plans, Charles II wanted everyone involved with the plot aggressively caught, tried and punished. This seems to have been due to Charles II determination to destroy Whig opposition in revenge following Whig efforts to exclude his brother James from the line of succession.

William Lord Russell was one of those caught up in the conspiracy. He was put on trial, where he would admit only that he had not given information about one of the conspirators, rather than having been an active participant in the plot.

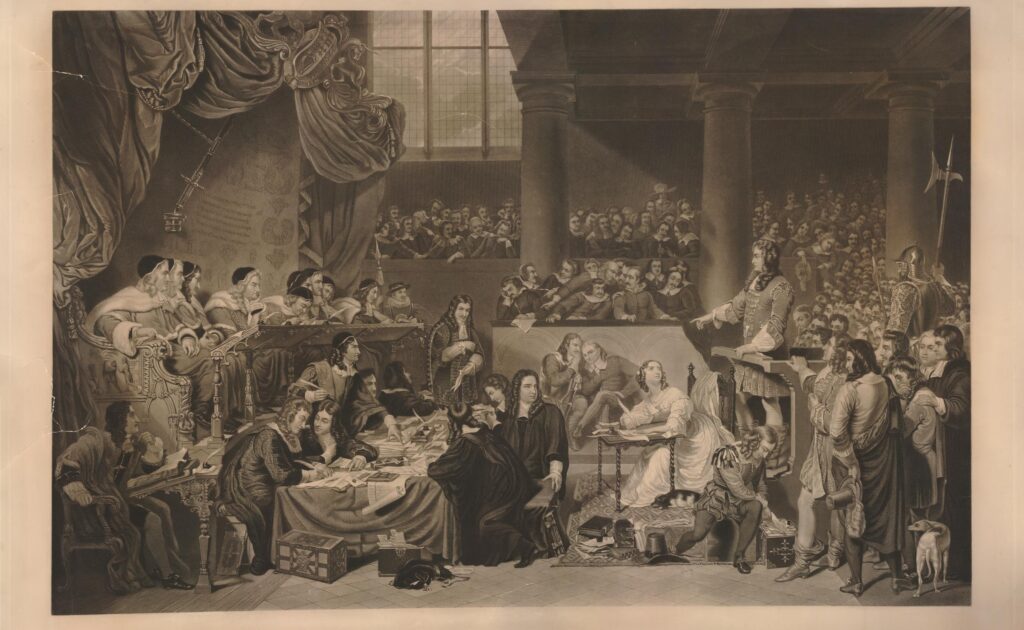

The following print shows the trial of William Lord Russell. He is standing at the witness stand on the right. His wife is at the small table in front of him, taking notes and looking up at her husband (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

Despite his protestations of limited involvement in the plot, and that it does not seemed to have been a well planned activity, he was sentenced to death.

Print from 1796 showing William Lord Russell’s last interview with his family (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

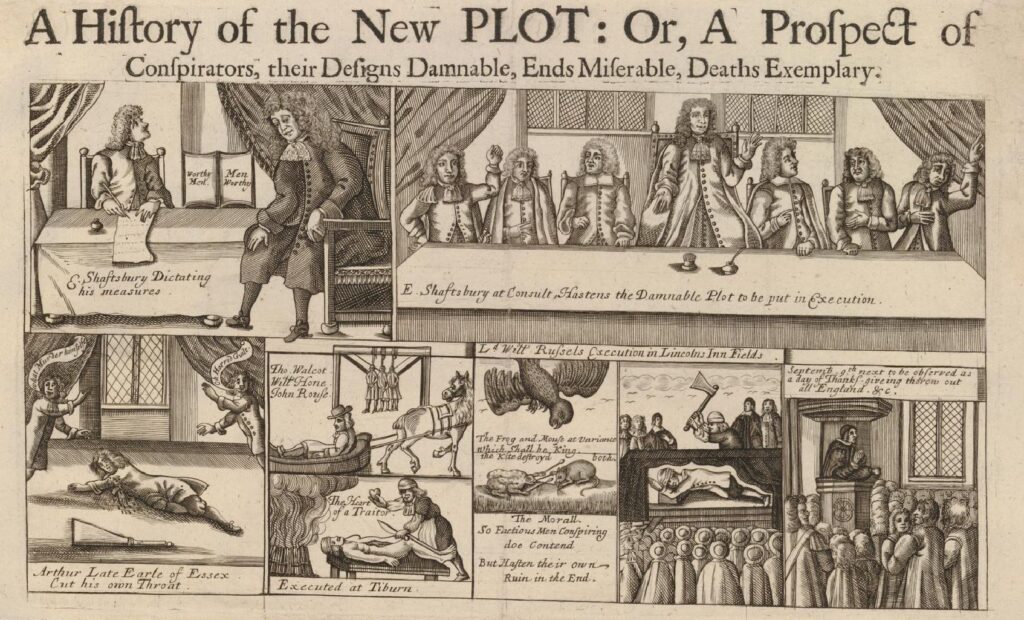

A number of pamphlets were published at the time, about the Rye House Plot, and the fate of the alleged conspirators. One of these graphically shows some of their fates (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

The images at the top show the 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, who was known to be one of the leading conspirators against a Catholic succession if Charles II died, and the spiritual leader of the Rye House plot. When the king had been ill, Shaftesbury had already convened a number of people sympathetic to the cause to discuss what should be done when the King died, and that an uprising should take place to enable Parliament to make the decision on the succession.

Shaftesbury’s attitudes to Charles II and his brother James led to him fleeing the country to the Netherlands at the end of 1682, however the journey had an impact on his health and he died in Amsterdam on the 21st of January 1683.

At lower left is Arthur, Earl of Essex who committed suicide in the Tower of London by cutting his throat. The two figures are saying that he murdered himself of horrid guilt.

The next panel to the right is showing Thomas Walcott and John Rousee being executed at Tyburn (I cannot tie down the second name to one of those executed at Tyburn). They were sentenced to be hung drawn and quartered, and the lower drawing showing “the heart of a traitor”.

To the right is a drawing showing a mouse and a frog arguing whilst a kite descends on both. The text reads:

“The Frog and Mouse at variance which shall be king. The Kite destroyed both. The Morall. So Factious Men Conspiring do Contend. But Hasten their own Ruin in the End.”

Then there is a drawing of William Lord Russell’s execution at Lincolns Inn Fields, and finally at lower right “September, 9th next to be observed as a day of Thanksgiving throughout all England.”

The drawings show only a small proportion of those executed, imprisoned or exiled in what was a very revengeful approach to sentencing. It took two strokes of the executioners axe to kill William Lord Russell, however perhaps one of the worse examples is that of Elizabeth Gaunt.

Elizabeth and William Gaunt were London Whigs and were active in the dissenting politics of the time. In 1683 she was living in Old Gravel Lane, Wapping.

James Burton was alleged to have been present when the Rye House plot was being discussed. As a result, Burton had been outlawed, and Elizabeth helped him escape to the Netherlands, by providing him with money and a boat from Wapping to Gravesend, from where to took a boat to Amsterdam. You can imagine him sneaking down one of the Thames Stairs in Wapping, late at night, to make his escape.

Burton later returned to the country as part of the Monmouth rebellion. He was captured whilst again trying to escape to the Netherlands, and to avoid a death sentence, he gave evidence that Elizabeth Gaunt had helped him escape following the earlier plot.

Elizabeth Gaunt was tried, and sentenced to death by being burned at the stake at Tyburn. She was burnt to death on the 23rd of October 1685. Such was the vindictiveness against anyone involved, however remotely, in the plot, she was not strangled before being burnt, as was the usual custom.

James Burton was from then on known as someone who would incriminate anyone, even those who helped him, in an attempt to save his own life.

The sentences passed seem to have been to act as a deterrence to would be conspirators, and also to anyone who may help a conspirator.

Elizabeth Gaunt was the last woman to be executed for a political offence (© The Trustees of the British Museum).

Although the Rye House plot failed, the ultimate aim of the conspirators did succeed.

James did become King James II on the death of his brother, Charles II.

James II and his wife, Mary of Modena had a son, confirming fears that the country would have a Catholic line of kings. A group of Protestant Earls, Viscounts and a Bishop invited William of Orange to the country to take the crown. William was married to Mary, the daughter of James II.

This resulted in the Glorious Revolution, where William of Orange and Mary jointly reigned, James II fled to France, the threat of a Catholic succession was removed and England had a Protestant monarch – all the aims of the Rye House conspirators.

And today there is a reminder of the plot with a simple plaque on the floor of the shelter at Lincolns Inn Fields.

Looking along the northern side of the fields – hard to believe that this was the site of a number of executions:

The public were not allowed in the fields after the railings were put up in 1735, however by the middle of the 19th century there was public campaigning to open up the field – this being such a large area of green, open space in a very built-up part of the city.

The London County Council purchased the field in 1894 from the Trust that had been maintaining the fields, and they were opened up to the public. The railings were removed in 1941 due to the need for iron for wartime weapons manufacturing. A real shame as these were over 200 years old.

New railings were installed in the 1990s, and the fields also had a tennis and netball courts and putting green built in the south-western corner. The central shelter was also built, which at times has been used as a bandstand.

A neat row of bins line the path to the shelter:

As befits such a place, there are a couple of 19th century monuments around Lincoln’s Inn Fields, including this drinking fountain, with the following religious message around the upper part of the fountain “The fear of the Lord is a fountain of life”:

Along the north of Lincoln’s Inn Fields is the house and now museum of Sir John Soane:

Sir John Soane, who was the architect of the Bank of England, moved into Lincoln’s Inn Fields in 1794, having rebuilt the house which he had purchased a couple of years earlier.

He eventually acquired numbers 12 to 14, the three houses in the above photo with the same darker grey brick and architectural style, although Soane added the façade to number 13, the central house which he completed, along with a rebuild in 1813.

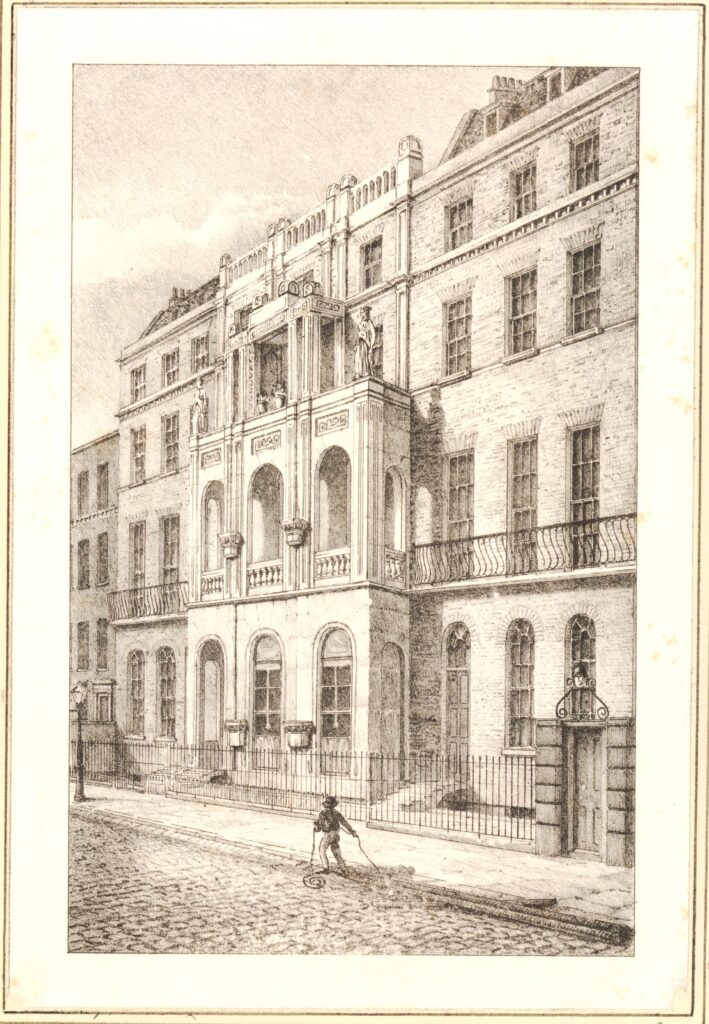

Sir John Soane’s house at it appeared in 1836 (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

Soane was a collector, and during his life he amassed a very large collection of sculpture, furniture, antiquities and paintings.

He died in 1837, and following an Act of Parliament he had obtained in 1833, the house and his collection was held in a trust, and opened to the public as a museum, which continues to this day, with many of the exhibits being as organised by Sir John Soane.

Along the western side is Lincoln’s Inn:

With the gateway into this side of Lincoln’s Inn. Both the above and below buildings are not that old, but I will save these for a future post on Lincoln’s Inn.

Another 19th century drinking fountain at the opposite corner of the fields to the first. This one is in memory of Philip Twells, who was a Barrister at Lincoln’s Inn, as well as being the MP for the City of London.

On the south eastern corner of Lincoln’s Inn Fields is this fine building. Once the home of the Land Registry, it is now part of the London School of Economics:

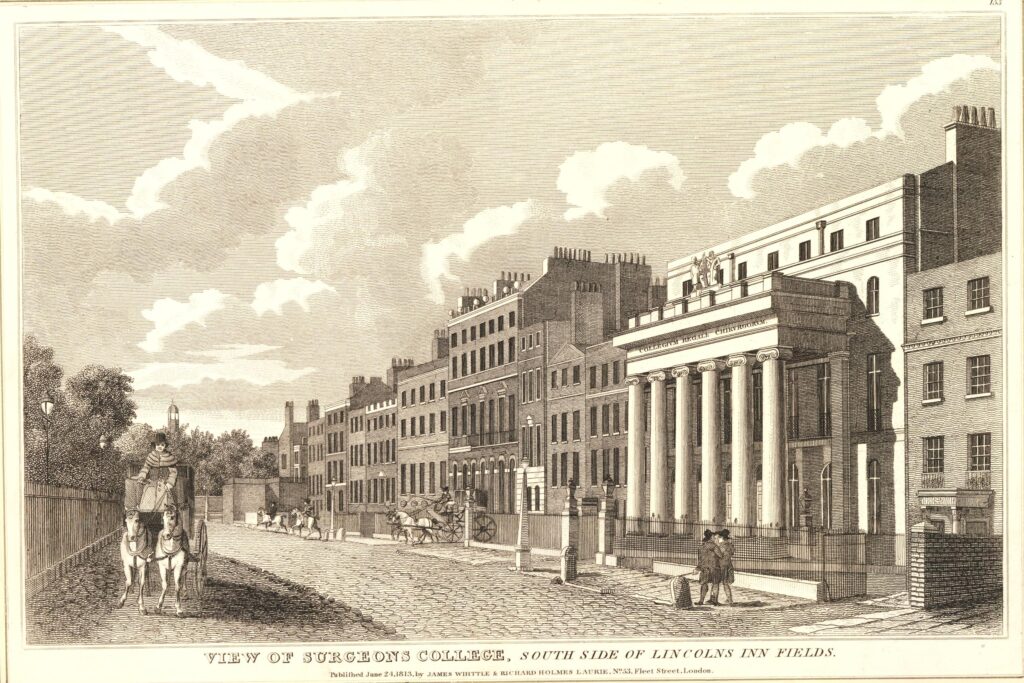

Also along the south side of the fields is the building of the Royal College of Surgeons:

The Royal College of Surgeons received their new Royal Charter in 1800, and built their new home in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. The building was bombed during the last war and was rebuilt, so is not fully an original.

The following print, dated 1813, shows the view along the southern side of Lincoln’s Inn Fields and shows how the post war rebuild of the Royal College of Surgeons building included additional floors at the top of the building (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

The same view today, where the horse and carriage has been replaced by cars, vans and bikes:

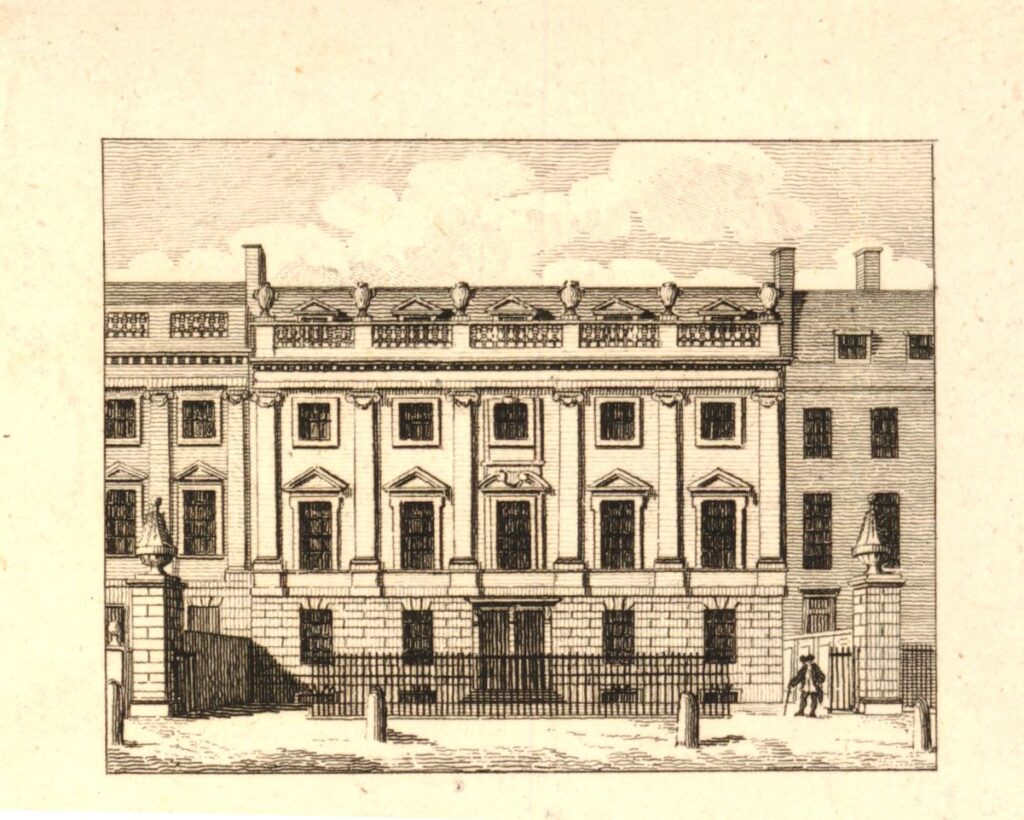

Almost all the buildings of Lincoln’s Inn Fields have been rebuilt since the original construction around the fields. There is one building that dates from the very first period of building, and this is Lindsey House, which was built between 1640 and 1641 (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

Lindsey House looks very much the same today:

Lindsey House has been attributed to Inigo Jones, however there is no firm evidence from the time to confirm this, but the style is typical of Jones’ work.

Whilst the exterior has changed little since construction in the mid 17th century, the interior is very different as in 1752 the house was divided in to two, and this work incolved the loss of much of the interior.

I had planned to cover more about the buildings that line Lincoln’s Inn Fields, however, as usual, I ran out of time. It is a lovely place to be on a sunny spring or summer day, and there is much to discover, including the simple plaque on the floor of the shelter, a plaque which hints at the politics and religious conflicts of the 17th century, and how vindictive the state could be to those who it considered a threat.