Manchester Square is the subject of this week’s post. Georgian architecture, a Marchioness who had intimate meetings with the Prince Regent and an original lane that once ran through fields and now runs through the streets of Georgian London.

Manchester Square is a short distance north of Oxford Street and a perfect example of how in London you can walk in a matter of minutes from streets crowded with people and traffic to a peaceful place that is full of history and wonderful architecture.

Manchester Square still has the much of the original Georgian and Regency period houses from when the square was built, along with an original London town house that occupies one full side of the square. In the centre of the square is a garden which looked fantastic when I visited on a sunny spring day.

Construction of Manchester Square was part of the Georgian expansion of London. The land formed part of the Portman Estate (as it still does) and a lease on a plot of land was granted to George Montagu, fourth Duke of Manchester who commenced construction in 1776 of a house on the north side of the square.

Other builders purchased leases on the other three sides of the square, the central gardens were laid out, and Manchester Square came into existence, named after the Duke, as was his house, which on completion in 1788 became Manchester House.

Soon after the completion of his house, the Duke died. The house was then purchased by the Spanish Government as their London embassy, a role it occupied until 1797 when the second Marquis of Hertford purchased the lease and renamed the house as Hertford House (and this is where the Marchioness of Hertford became a rather scandalous London figure – more later in this post).

The second Marquis died on 1822 and the house passed to the third Marquis, then in 1842 to the fourth Marquis of Hertford who was a collector of art, furniture, china etc. scouring the auction rooms of Europe to put together a very large collection that was stored in his houses in London and Paris. The fourth Marquis of Hertford died in 1870. He was unmarried and with no children, left his entire collection to his friend Sir Richard Wallace (who was also a collector). Wallace made a number of changes and extensions to the house to form the building that we see today.

The combined collection became known as the Wallace Collection, and on the death of Sir Richard Wallace, the collection was bequeathed to the nation, and it is this collection which is now housed in Hertford House

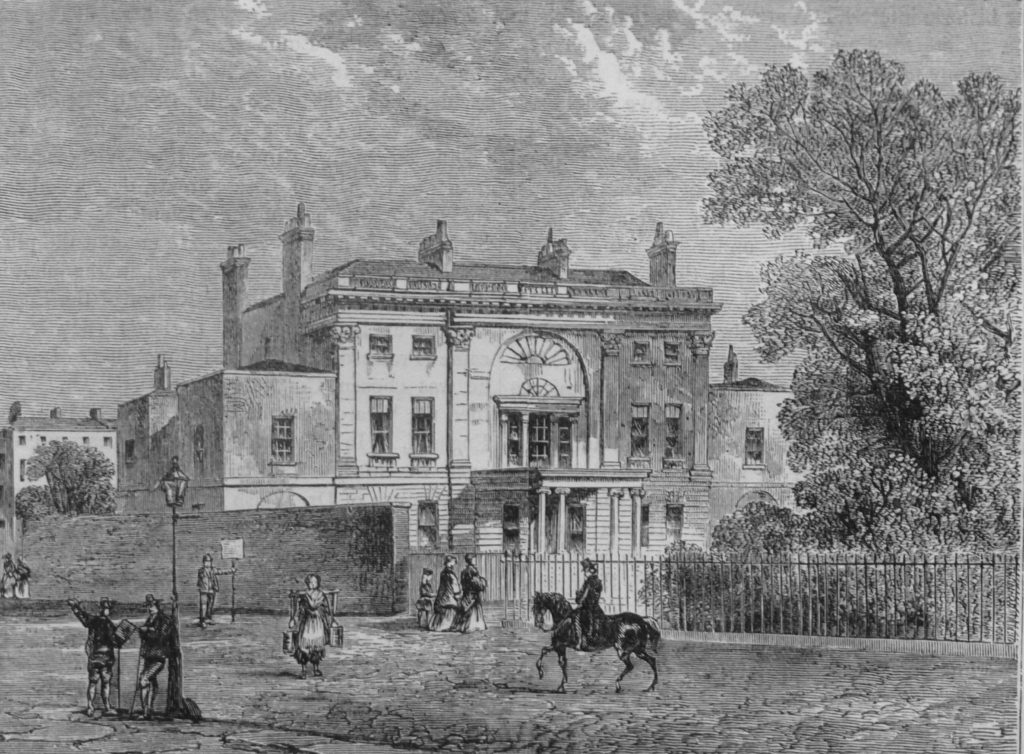

Hertford House, home of the Wallace Collection in Manchester Square:

Manchester House soon after completion and before it became Hertford House:

Standing in Manchester Square it is hard to believe that you are only a couple of minutes from Oxford Street. The central gardens are an oasis of green, spring blossom is blowing across the street and the few people around are either heading to the Wallace Collection, or using the street as a local parking place for Oxford Street.

The original plan for Manchester Square was for a church to be built in the central square, however this did not get built and the gardens were laid out between 1776 and 1788.

The second Marquis of Hertford who purchased Manchester House and renamed it Hertford House was a good friend of the Prince of Wales (who would later become George IV) and the Prince of Wales was a regular visitor to Hertford House, however it was his interest in the Marchioness, Lady Hertford that appears to have been his main reason for making the journey to Manchester Sqaure. It was written at the time that “The Prince does not pass a day without visiting Lady Hertford, indeed so notorious did these calls on ‘the lovely Marchesa’ become that a scurrilous print inserted in its columns the following advertisement: Lost, between Pall Mall and Manchester Square, his Royal Highness the Prince Regent”.

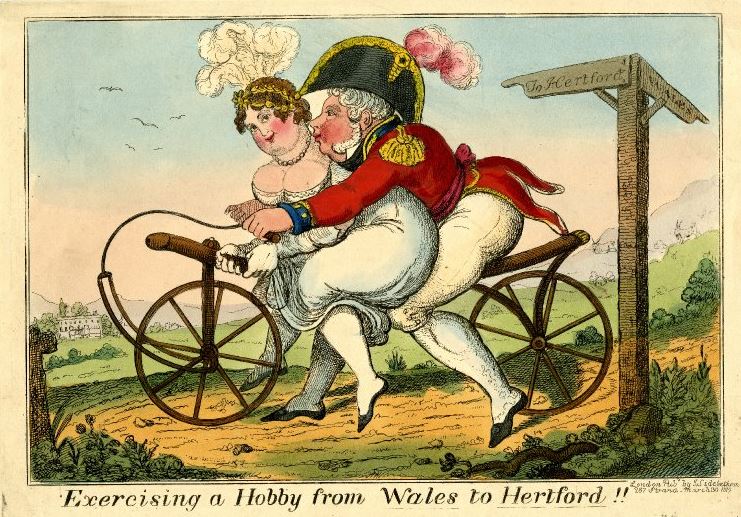

The relationship between the Prince of Wales and Lady Hertford was also the subject of a number of satirical cartoons. The following cartoon from 1819 shows Lady Hertford and the Prince Regent, the Prince of Wales on one of the new velocipedes. The signpost on the left is pointing to Wales and Hertford.

©Trustees of the British Museum

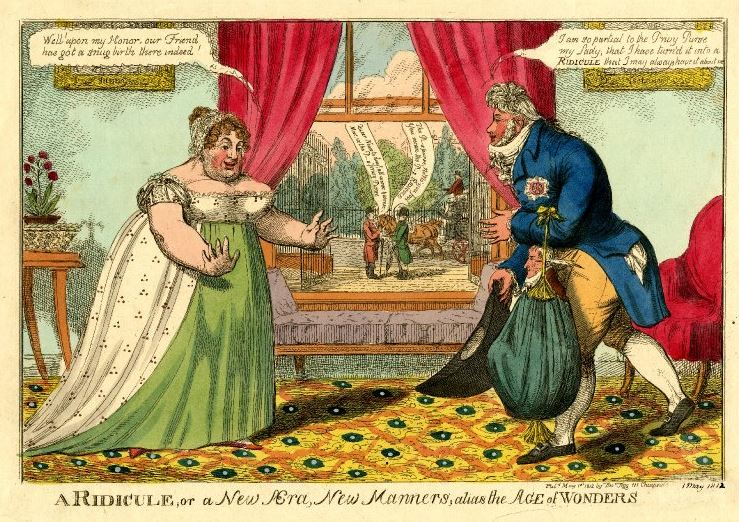

The following carton shows a room in Hertford House with Manchester Square seen through the windows. The Prince Regent on the right is walking towards Lady Hertford. The Prince is holding the Privy Purse and the small character inside the purse is John McMahon who at the time was the keeper of the Privy Purse and the official private secretary to the Prince.

The Prince is saying to Lady Hertford: “I am so partial to the Privy Purse my Lady; that I have turn’d it into a Ridicule that I may have it always about me.” and she replies: “Well! upon my Honor, our Friend has got a snug birth there indeed.”

The two men talking in the square seen through the window are talking about the bad news of the day being that McMahon is now the keeper of the Privy Purse (and will do exactly what the Prince requires) and the Prince is therefore holding the Privy Purse up to ridicule.

©Trustees of the British Museum

The Marchioness, Lady Hertford was considered one of the reigning beauties of the day. The Irish poet, Thomas Moore, initially a good friend of the Prince wrote of Lady Hertford:

“Or who will repair unto Manchester Square,

And see if the lovely Marchesa be there?

And bid her to come, with her hair darkly flowing,

All gentle and juvenile, crispy and gay,

In the manner of Ackerman’s dresses for May.”

Portrait of Isabella Anne Ingram Shepherd, 2nd Marchioness of Hertford by Sir Joshua Reynolds:

©Trustees of the British Museum

When Manchester Square was built, London was expanding rapidly to the west and north. The area to the north of Oxford Street was being turned from fields to wide, formal streets and squares. To see what the area was like immediately before Manchester Square was built, I turned to John Rocque’s map of 1746, just 30 years before construction started on Manchester Square.

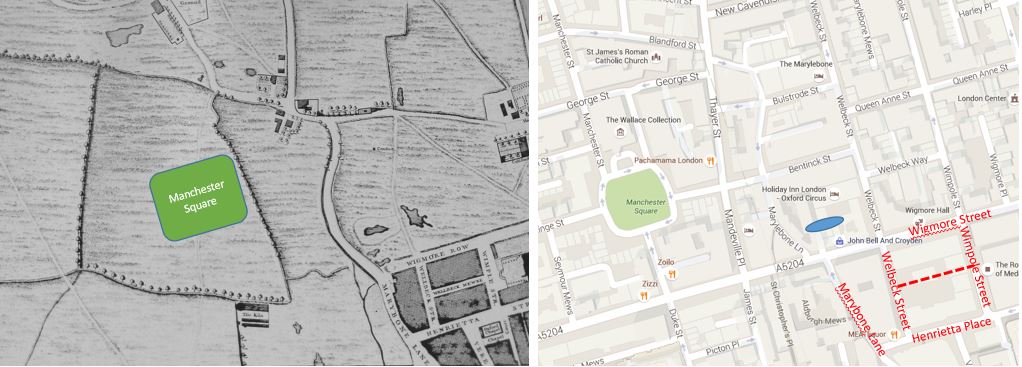

The following map shows the area on which Manchester Square would be built.

I wanted to see if I could place Manchester Square in Rocque’s map and whilst doing so, found what I believe to be an original street remaining from when the area was all fields.

See the two maps below. On the left is Roqcue’s map of the area and on the right a Google map of the same area. If you look to the lower right of both maps, the 1746 extent of building can be seen.

I have shown the modern street names in red on the Google map. In the 270 years since Roqcue’s map there have been some subtle changes in street names:

Wigmore Row in 1746 is now Wigmore Street

Wellbeck Street is now Welbeck Street (it has lost an ‘l’)

Wimple Street is now Wimpole Street

Henrietta Street is now Henrietta Place

The dotted line in the Google map is the location of Wimple Mewse which has disappeared since the Rocque map.

The extent of the building in 1746 is along Marybone Lane, this is now Marylebone Lane. I have marked the name in red in the Google map, however where it gets really interesting is if you follow Marylebone Lane north across Wigmore Street you will see that it curves to the left, following roughly the same curved path as Marybone Lane in 1746.

Marylebone Lane today is different to the majority of other streets in the area. It is a much narrower street and is not a formal straight street as are nearly all the others in the area. Also, look just above Wigmore Row in the 1746 map and Marybone Lane curves to the left to avoid a pond in the field, I have marked the rough position of this pond on the Google map by the blue oval.

I suspect that Marylebone Lane today follows the same alignment as Marybone Lane when it originally ran through open fields and the curved route of today avoids a long lost pond that is now under the Holiday Inn Hotel between Welbeck Street and Marylebone Lane.

I have marked my estimate of where Manchester Square would later be built on the 1746 Roque map, in the middle of a rather large field.

If I am right, it is remarkable that with the considerable 18th and 19th century development of this area, and the laying out of wide streets in straight lines, it is still possible to walk down a street that once ran through open fields and is probably many hundreds of years old.

After that diversion, let’s return to Manchester Square to admire the architecture.

Many of the buildings surrounding the square have the wrought iron balconies of the late Georgian / Regency period.

And as you might expect, there are plenty of Blue Plaques to be found. This one for Alfred Lord Milner, who started as a journalist, then was a civil servant before becoming High Commissioner for South Africa and Governor of the Cape Colony during times of considerable tension which led to the 2nd Boer War. On return to London he was chairman of the Rio Tinto mining company, a Director of the Joint Stock Bank and continued to have a number of roles in the Government, continuing to travel widely.

The south west corner of Manchester Square.

Below is the south east corner of Manchester Square. The windows in these buildings clearly show the impact of the 1774 Buildings Act which took the 1709 requirement for the windows to be recessed by 4 inches and added the requirement for the sash box to be hidden behind the brickwork. The main reasons for these changes were to prevent the spread of fires and the risk of the sash window falling out, but was also driven by the fashion of an austere and simple window design.

Blue plaque to Sir Julius Benedict, a German composer and conductor who spent the majority of his life in London.

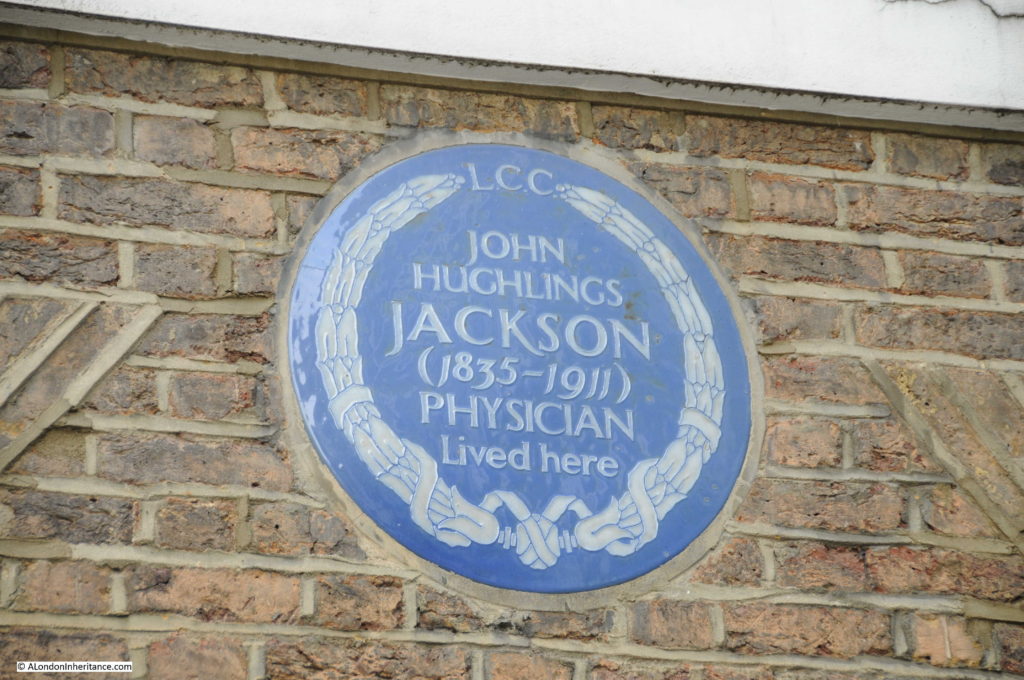

And in the same corner of the square a blue plaque to John Hughlings Jackson, a prominent neurologist, whose work on epilepsy resulted in an improved ability to diagnose and understand the condition.

Blocked up windows on the side of one of the buildings in Manchester Square, possibly to reduce the amount of Window Tax paid by the occupiers. The windows are blocked on the side street from the square so the main frontage of the building onto Manchester Square has the full complement of windows. The owner would not want the view of his house facing to the square to be any different from his neighbours and savings would be made where parts of the house were less visible.

A different architectural style on the north east corner of Manchester Square:

One of the streets leading off Manchester Square (to the right of Hertford House) is Spanish Place – the name recalling the Spanish connection of Hertford House when it was home to the Spanish Embassy.

Some of the original houses in Spanish Place. As with many of the houses in the main square, they have the Georgian form of windows as well as the fanlight, arched window above the door:

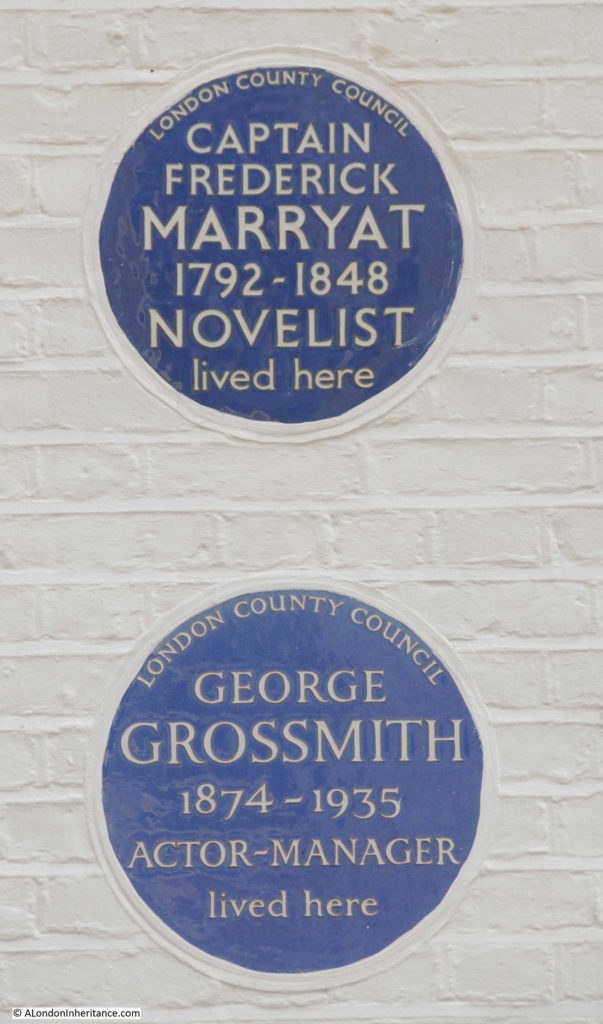

With yet more blue plaques. This time to Captain Frederick Marryat, a Royal Naval officer and author and also to George Grossmith, who was a theatre director, actor and playwright.

Manchester Square and the surrounding area is fascinating. This area grew considerably during the Georgian period as London expanded rapidly to the west and north of Oxford Street and there are many fine streets and squares to be found, and Marylebone Lane looks to be a survivor from the time when this area was all fields.

The legacy of the 4th Marquis of Hertford and Sir Richard Wallace with the Wallace Collection housed in Hertford House is well worth a visit and whilst walking the rooms of Hertford House you are also walking the site of the Prince Regent, the Prince of Wales many visits to meet with the Marchioness, Lady Hertford.