Walk around the City of London today, and the majority of working buildings are those in use as office space. Today, there is very little, if any, small manufacturing industry in the City, although once the streets would have been full of small businesses, manufacturing a wide range of products.

This was not “dirty” industry, this was relegated to the south of the river, to the north, and particularly, to east London.

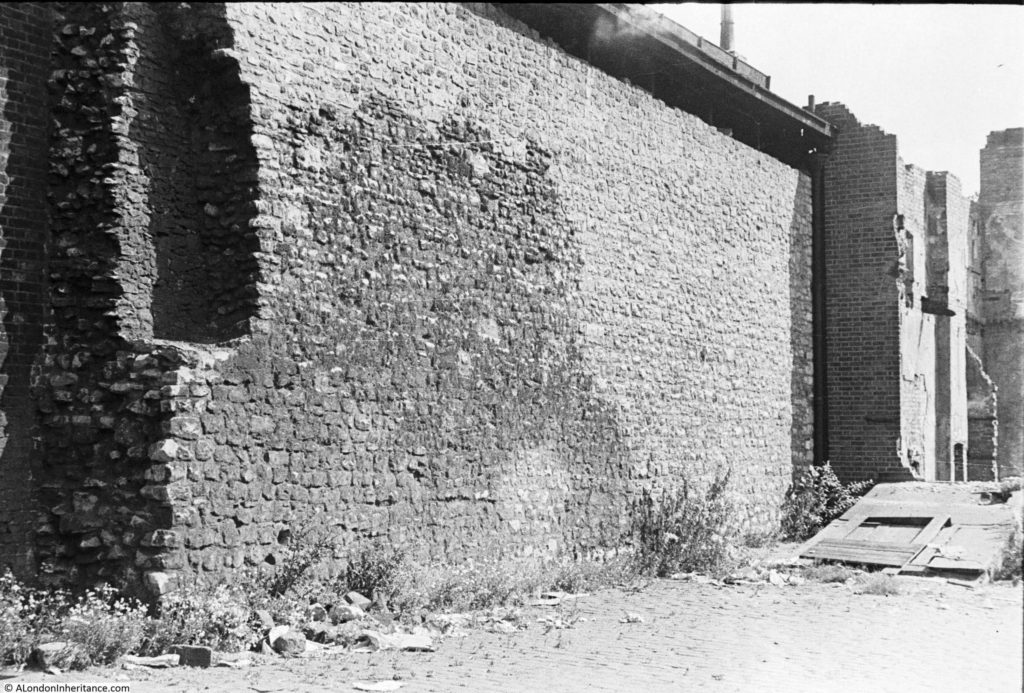

Despite the multiple phases of rebuilding in the City since the last war, there is one place where we can still see the ruins of the buildings that once supported multiple small manufacturing business, buildings that followed the alignment, and had their foundations built on the original Roman city wall, and where extensive Roman remains were found after wartime destruction – all in Noble Street:

Walk to the western end of Gresham Street, and the last street on the right, next to the church of St. Anne and St. Agnes is Noble Street. On the western side of the street, just past the church, are the ruins of a bombed building, as seen in the above photo.

A quick look behind the building reveals the old surrounds of the church, now almost impossible to access:

The ruined walls still retain a small part of the interior decoration:

Next to the above building, we can look north along Noble Street. A narrow City street, today with new office blocks along the eastern side, with the remains of more late 18th to early 20th century buildings along the west:

Which we can see by looking over the wall in the above photo, down into the gardens and brick walls:

The whole area within the above photo is a Scheduled Ancient Monument. The Historic England listing states that the area includes “buried remains of part of London Wall, the Roman and medieval defences of London, and part of the west side of Cripplegate fort. Remains of property walls of the late 18th-20th centuries built using the London Wall as their foundations are also included”.

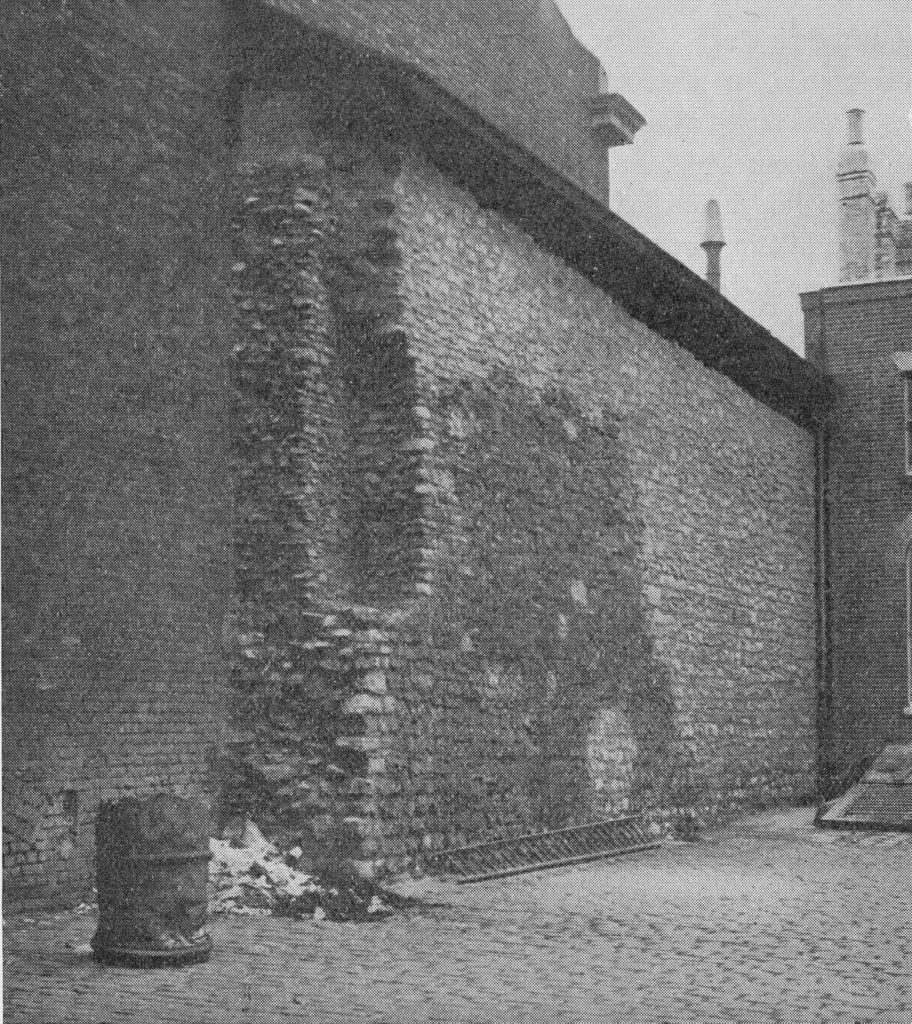

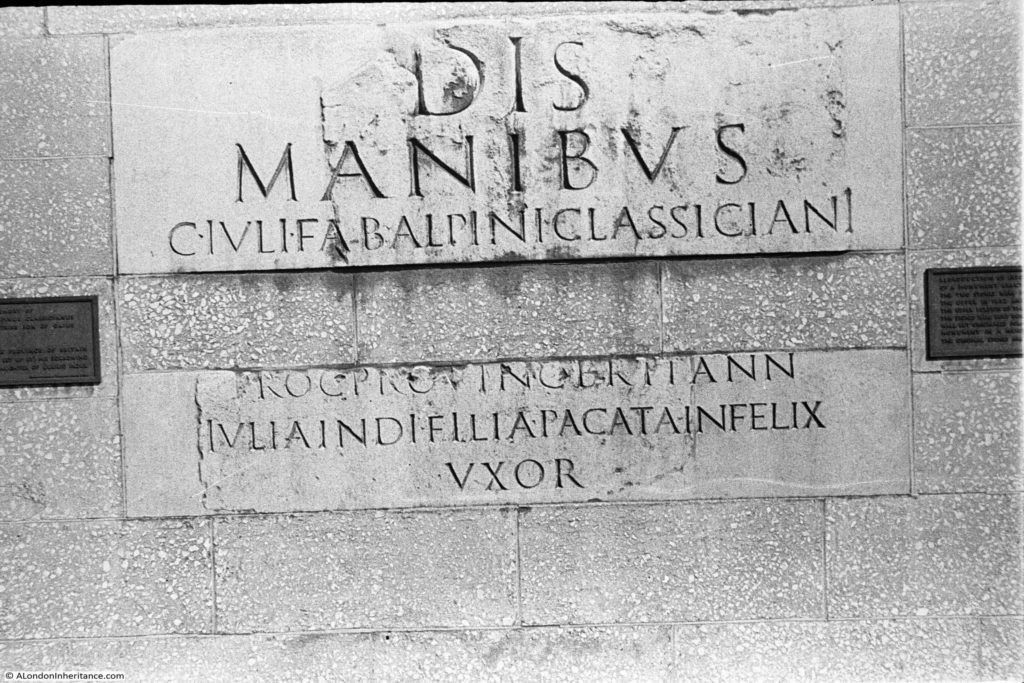

To understand more about the remains here, I turned to my go-to book about post war excavations across the City – The Excavation of Roman and Mediaeval London by Professor W.F. Grimes. There is a good amount of details about Noble Street in the book, which he sums up as “This consists of the double Roman wall, still carrying in one place at its northern end a mediaeval fragment; an internal-turret of the fort; and the south-west angle, with its turret, the junction of the Aldersgate length of the city wall and the surrounding portion of Bastion 15. Final consolidation of these remains awaits completion of redevelopment schemes in the area.”

The mention of a fort in the above extract from the book refers to one of the earliest substantial Roman features in the City of London, a fort built at the north west corner of the City over what would become Cripplegate.

The Roman wall under the remains of the bombed buildings in Noble Street formed part of the western wall of this fort, dating from between AD 120 and 150, and later strengthened by building a new interior wall up against the original external wall, when the fort was incorporated within the late 2nd century City wall.

At the southern end of the Noble Street is a key feature which helped to confirm this, along with the changes in direction of the wall.

Grimes excavations found below the basement of number 34 Noble Street, the foundations of a “small sub-rectangular turret, built against the inner face of the wall on the crest of the curve. Taken in conjunction with the rest, it was immediately recognisable as the quite typical corner turret of a Roman fort”.

The curve refers to the way Grimes found the wall unexpectedly curve eastwards below the cellar of number 33, but on digging down in number 34, this was found to be the wall of the turret, and within number 34, the turret was found to be on the corner, where the wall then turned westwards to run to Aldersgate.

Looking down today, we can see part of the remains of this rectangular turret:

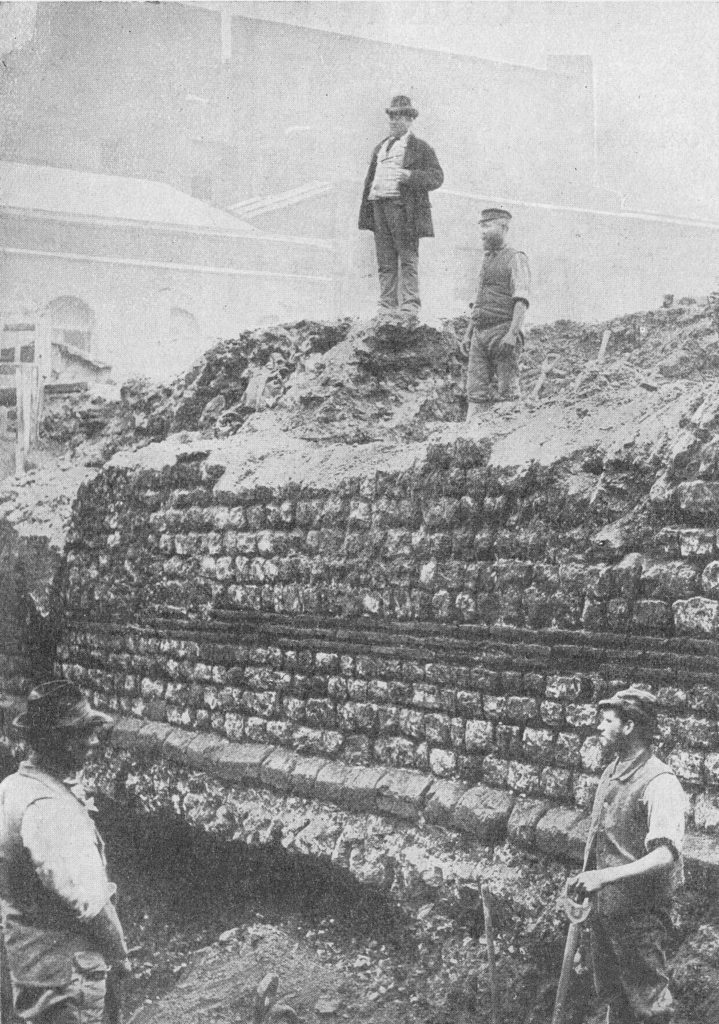

Grimes book includes a couple of photos of the excavations along Noble Street. The caption to the first reads “Noble Street, the junction of the fort wall (A) and the City wall (B) with the culvert through the later overlying the fort ditch. The fort wall can be seen approaching the modern wall in the background, is broken by a modern concrete foundation”:

Also in the book is the following photo, which was taken from a height looking down into the remains at the southern corner of Noble Street. The caption to the photo reads: “the south-west corner turret of the Roman fort, with, to right, the double wall curving towards it from the north and Roman city wall going westwards from it”:

Most of these remains have been covered up today, but are still below the surface – hence the status of a Scheduled Ancient Monument, and there are only small parts, such as the south west corner, where some of these remains can be seen.

The street is probably of a very considerable age, as it runs along the front of buildings constructed up against the wall, however the name is not (in London terms) that old. Henry Harben, in a Dictionary of London (1918) provides the following “First mention: On a tradesman’s token, 1659. Perhaps in early times Foster Lane extended further north than at present and included the present Noble Street. It may have been renamed ‘Noble’ Street after an owner or builder”.

As usual, with features many centuries old, much is speculation. The comment about Foster Lane does make sense, as Foster Lane and Noble Street were once a continuous street, before the construction of Gresham Street which cut across the two and made a clear separation.

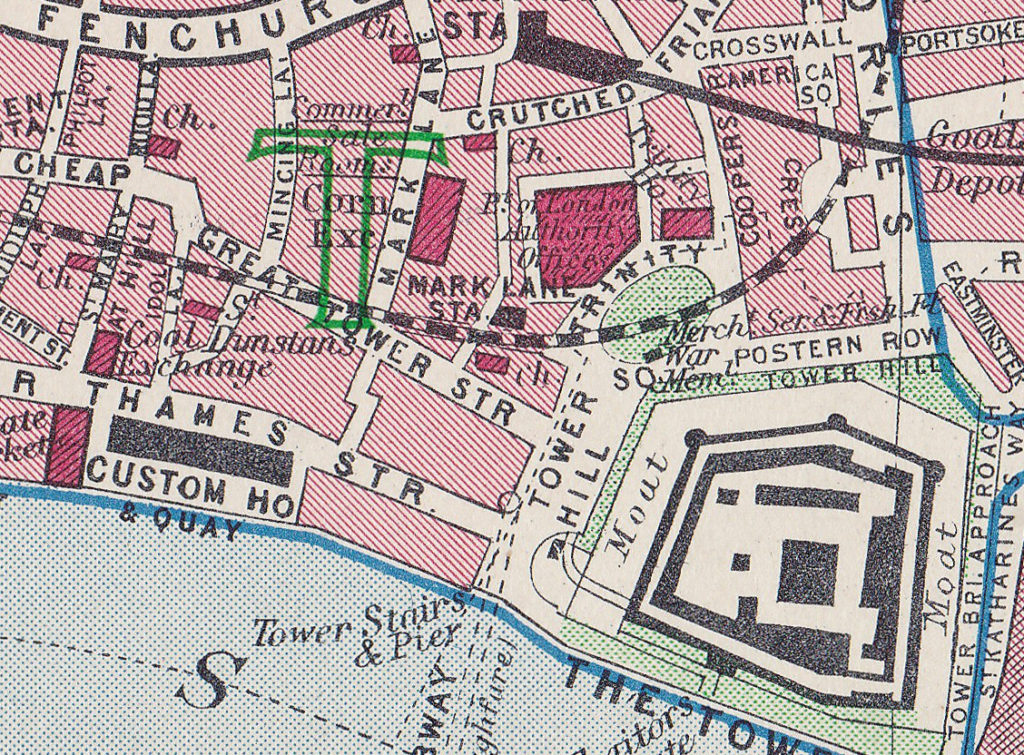

William Morgan’s map of 1682 shows Noble Street as a continuation of Foster Lane in the south. Note that in 1682, the City wall is still a substantial feature to include in a map. The way the wall runs south, then turns to the west, as confirmed by Grimes, can clearly be seen. Also, in 1682, there is still an Aldersgate. This is not the original gate, but a 1618 rebuild of the earlier medieval gate. Aldersgate would not be demolished, and the street cleared until 1761:

There are a few numbered references along Noble Street. These are:

- 420 – Lillypot Lane

- 421 – Oat Lane

- 422 – Scriveners Hall

- 423 – Fitz Court

The entrance to Scriveners Hall, or as it was by the time of the print (1854) Coachmakers Hall:

Image: © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

The following extract from an Aldersgate Ward map from William Maitland’s Survey of London (1755) again shows Noble Street and Foster Lane:

The 1914 revision of the OS map shows Noble Street much as it must have been prior to wartime bombing, with the buildings shown along the western side of the street, which today can still be seen as ruins.

I have marked a number of key features on the map (Map ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“:

Fascinating that at the start of the 20th century, the alignment of the Roman fort and city wall can still be seen.

The wall continued north across Falcon Square, between Castle Street and Monkwell Street, where Grimes found more Roman and Medieval features, including the bastion shown on the map, and a second, hidden bastion. I wrote about this stretch of the wall in the post at this link.

Moving to the early 1950s, and we can see the considerable extent of wartime damage, with no buildings, and only a couple of ruins, shown along both sides of Noble Street. Much of this damage was caused by bombing during the night of the 29th December, 1940, when fires raged through the area surrounding and to the north of St. Paul’s Cathedral (Map ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“:

The remains of the buildings along the western edge of Noble Street were not even considered worthy of marking as ruins in the OS map:

There is a parish boundary marker on the rear wall of the above photo. The marker states that the boundary of the parish of St, Botolph, Aldersgate, extends 20 feet southward of this wall. I have always wondered where the plaque was originally located, as it is currently on the internal side of an east / west facing wall:

Many of the ruins are of quite substantial structures:

The title of the post referred to Noble Street and the ruins of London’s industry, and we can get a very comprehensive picture of this industry and commerce by looking at some of the old street directories of London, and the 1910 Post Office directory provides a listing from a time when all the ruins we see today, were in use, starting at the south east corner of the street:

In the above listing, we can see that at numbers 2 and 3 was the Post Office Tavern. In 1848 this was known as the Post Office Hotel, as in the Morning Advertiser on the 6th December, 1848 there was an advert for: “The Post-Office Hotel, Noble Street, Cheapside. The Valuable Lease And Goodwill. Mr. Daniel Cronin is instructed by the Assignees of Mr. Jasper Taylor, a Bankrupt, to Sell by Auction, at Garraway’s on Tuesday December 27th at 12, with possession of the above very excellent property, eligibly situate in the immediate vicinity of the busiest part of London, and constructed for the conduct of a first rate trade ion all its branches; held for an unexpired term of 34 years from Christmas 1848, at the low rent of £100 per annum”.

The directory starts from the south eastern side of the street, at the junction with Gresham Street. These directories usually list the street junctions, making is easy to work out the numbering and locations of businesses listed, and the directory does include those along the eastern edge – Lilypot Lane, Oat Lane and Fitchett’s Court, however the map does not state where Falcon Square to the north is reached, and the numbers start along the western side.

Fortunately, the details in W.F. Grimes account of excavations helps.

He wrote that the turret at the very south of the open space we see today, was found under number 34, with number 33 next to the north, so using the listing, we can see that in 1910, number 34 was occupied by:

- Alex Strauss & Co – Millinery, ornaments

- Hemken & MacGeagh – Manufacturers agents

- Glasser & Co – Ladies belt manufacturers

I wonder if they ever realised they were working on top of a key junction of the old Roman fort / wall and a Roman turret?

The building adjacent, on the north of the one with the turret, was number 33, which was occupied by:

- Egisto Landi – Confectioner

- Frederick Rolinson – Lace agent

- Hugh Sleigh & Co – Sewing silk manufacturer

- Richard Chas Burr – Manufacturers agent

- Joseph Johnson – Manufacturers agent

- Victor Wolf – Manufacturers agent

- M. Bloch & Co – Cape merchants

- Albert Edward Hondra – Manufacturers agent

And continuing with the numbers as they head below 33 and 34, we can see the occupants of the ruins that continue north along Noble Street:

There are a number of common factors across the listing, which show how Noble Street was occupied during the first half of the 20th century (and almost certianly for much of the 19th century):

- Many of the buildings were of multiple occupancy. Where we see a name with the title of Manufacturers Agent, we can imagine one person occupying a room, buying and selling the finished products from the street, or buying and selling the raw materials used in many of the manufacturing businesses.

- Almost every building had a manufacturer of some type. These were small manufactures, mostly connected to the clothing trade, for example making gloves, handkerchiefs, hats, needles and pins. There was a “Galloon Manufacturer” at number 31 – a galloon was a heavily decorated woven or braided trim, so a product which would be used as part of a larger item of clothing

- The number of businesses show how busy this relatively small street would have been in the first half of the 20th century. People coming and going to the buildings, raw materials and finished products being moved

- The type of manufacturing shows how this area was so badly damaged by incendiary bombs during the night of the 29th of December 1940. Nearly every building would have been storing inflammable materials, and this type of industry was very common in the streets to the north of Gresham Street, including across what is now the Barbican. A fire would have taken hold, and spread very quickly. Even without bombing, fires were still frequent ( see my post on the Great Fire of Cripplegate ).

The listing concludes with the businesses from the corner of the present day southern end of the ruins, down to the junction with Gresham Street:

Noible Street had been a place of industry and manufacturing for many years before the above 1910 Post Office directory. The British Museum have a collection of trade cards from businesses within the street, and the following are a sample of these, starting with the following dating from around 1800, of Ashworth, Ellis, Wilson & Hawksleys, Silversmiths & Platers from Sheffield; who had their London Warehouse at 28 Noble Street:

Next is the trade card of Joseph May, an engraver who worked at number 4 Noble Street in the 1780s:

George Yardley was a carver and gilder in Noble Street in the mid 18th century:

All of the above three images are: © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Many of the Noble Street manufacturers resorted to some unusual methods to sell their products. For example, in January 1897, J. Scott of the City Umbrella Company at 1 Noble Street ran a competition for Valentines Day offering cash prizes to those who purchased umbrellas.

To qualify they first had to complete the following words by finding the missing letters. These were all examples of articles of daily foods in the late 1890s:

You then had to send your answer, along with an order for an umbrella to stand a chance of winning a first prize of £50, second prize of £25, 4th of £15 and 5th prize of £10. There was also a prize of £50 to the person who ordered the most number of umbrellas.

The individual winnings cannot have been much, as the prize money was divided across all the correct entries, so everyone who got the answers correct, and ordered an umbrella, received a share of the over prize.

Towards the north end of the ruins:

At the northern end of Noble Street, at the junction with London Wall (the area which was Falcon Square, and opposite the location of St. Olave, see this post from a couple of weeks ago) is a stretch of surviving ragstone medieval wall which stands up to 4.5 metres in height:

This medieval wall survives because it was incorporated into the structure of the building which stood on the site.

Looking back along the garden and ruins along the eastern side of Noble Street:

The ruins are silent now, but they do act as a reminder of the trades that once occupied so many streets across the City of London, when industry and manufacturing worked alongside commerce and office work.

Noble Street is also a p[lace which may have nurtured my interest in history, and London history in particular. When we were children, Noble Street was where my father parked when he drove up to London for a weekend walk, and I do remember peering over at the ruins as a child. Noble Street was the starting point for many walks across London.