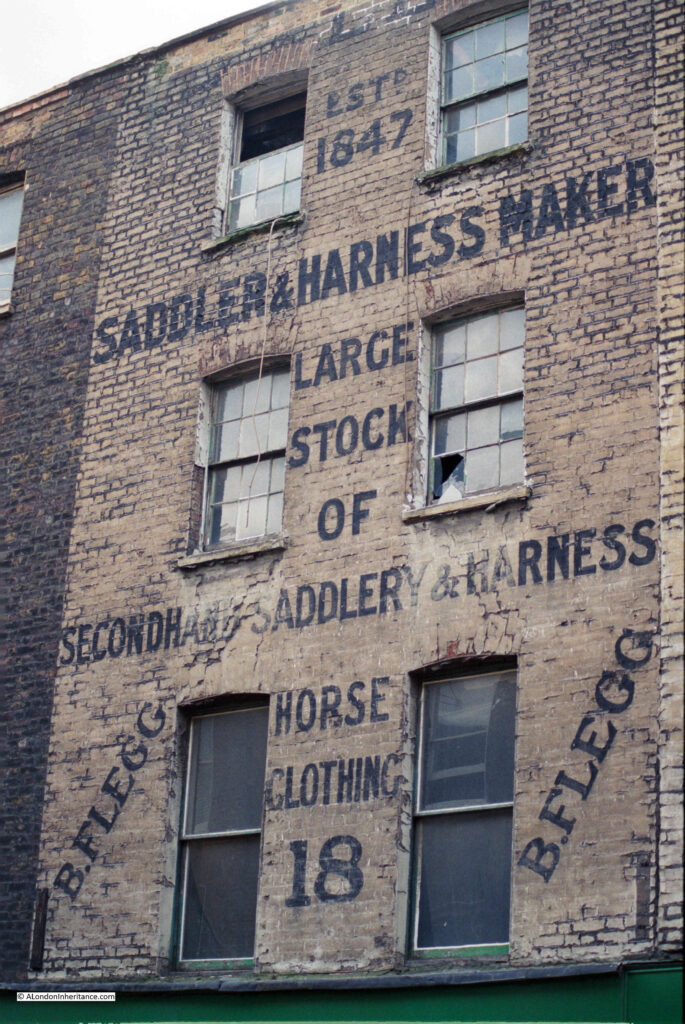

The following photo shows a brick terrace house, advertising a saddler and harness maker, but in a rather poor condition. We are in Monmouth Street in Seven Dials and the photo was taken by my father in 1984.

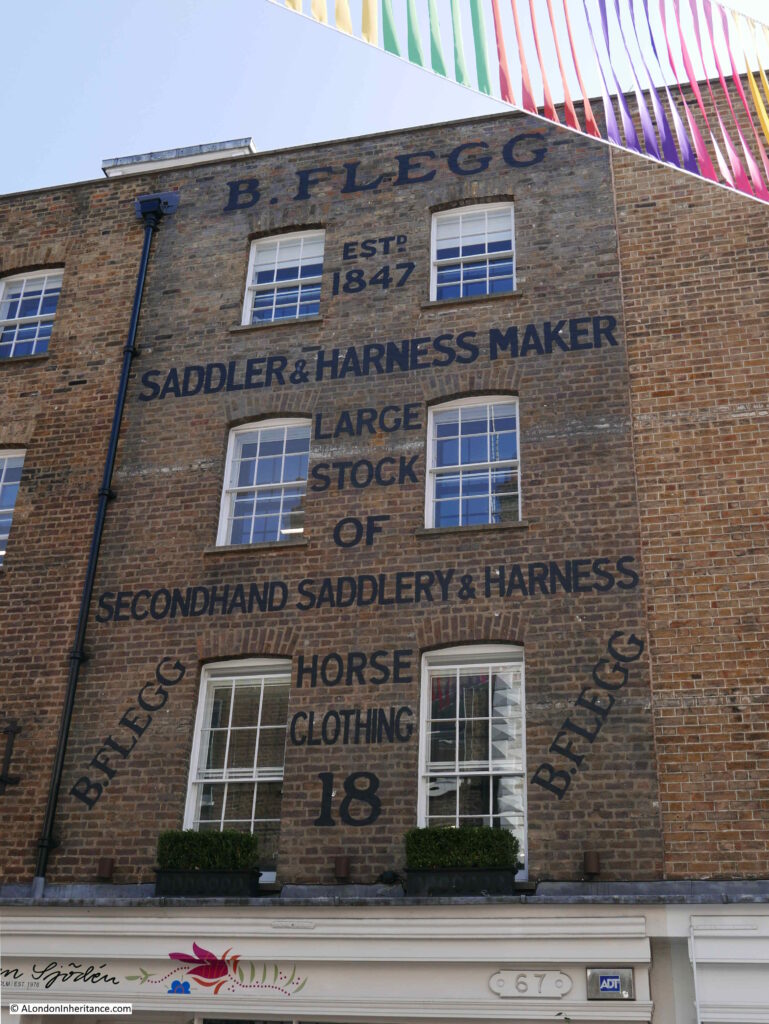

Thirty six years later and the building is in a far better condition, with the advertising signage restored.

I was going to try and be clever and title the post “Seven things about Seven Dials”, but as I dug into the history of the area there are far more than just seven things of interest.

The sign is advertising the business of B. Flegg, a Saddler and Harness Maker, established in 1847.

B. Flegg was a William Flegg and the building in Monmouth Street was not his only premises. I suspect this may have been his central London sales room, where he would sell everything needed for the thousands of horses that kept London moving in the 19th century.

William Flegg’s main location seems to have been on the Old Kent Road in south London where he occupied numbers 585, 586 and 592. Adverts in the South London Chronicle stated that he had “Stable utensils of every description. Whips and all kinds of horse clothing always on hand. A waggonette to let, to hold four or six persons”.

It could be that saddler and harness maker was a family trade and that the family were from south London. As well as William Flegg there was an H. Flegg, also a saddler and harness maker, who had premises at 7 Deptford Bridge, but had to move to 2 Church Street, Deptford in 1880 due to rebuilding of the bridge over the Deptford Creek.

Flegg is not that common a name so I suspect that H. and William Flegg were related.

The final references to the name Flegg as a saddler are in 1905, when a George Flegg, aged 40 and a saddler of 654 Woolwich Road, Charlton was found drunk in Woolwich Road and fined two shilling and six pence, or three days if he did not pay the fine.

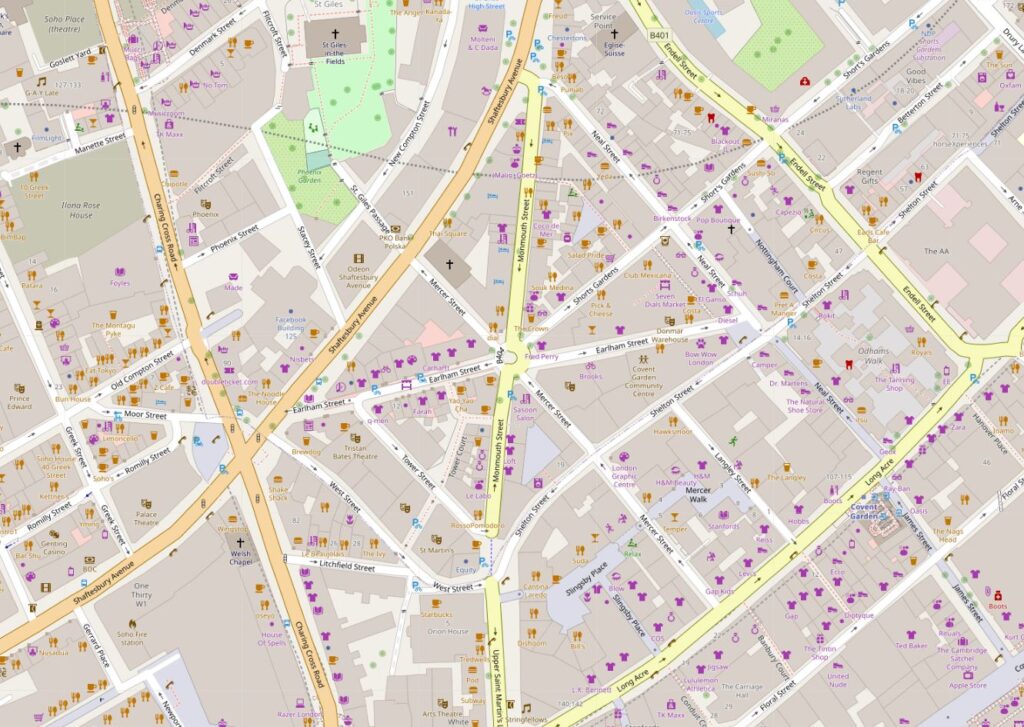

Monmouth Street is the street leading off to the south from the central Seven Dials junction, just to the east of Charing Cross Road and south of Shaftesbury Avenue. The seven streets radiating out from the central junction form a distinctive pattern on the map (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

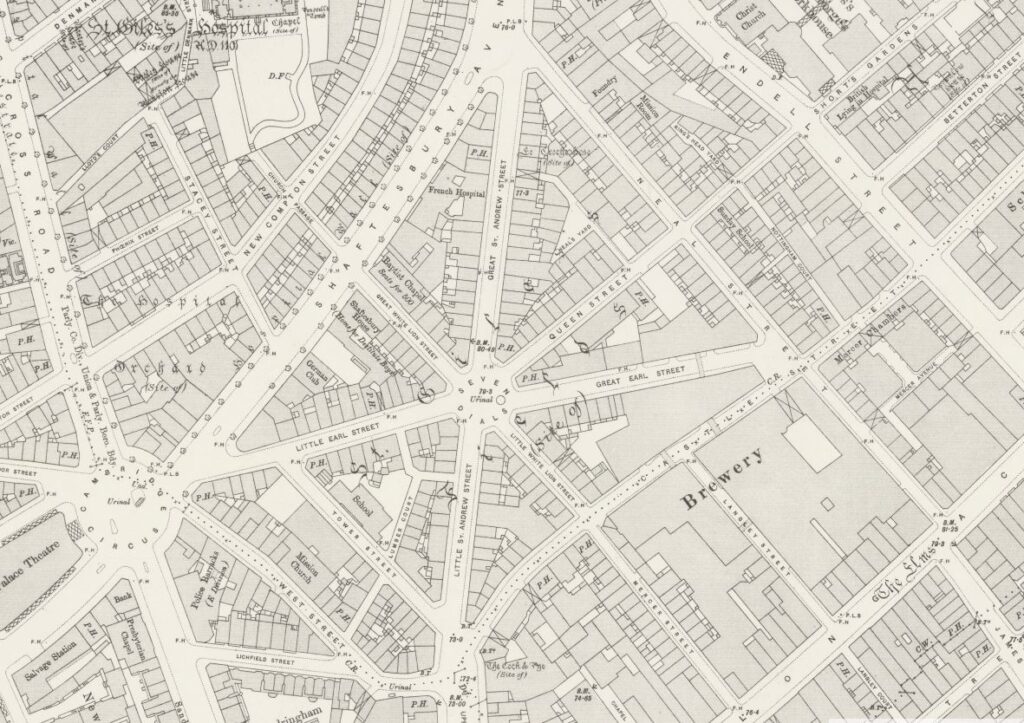

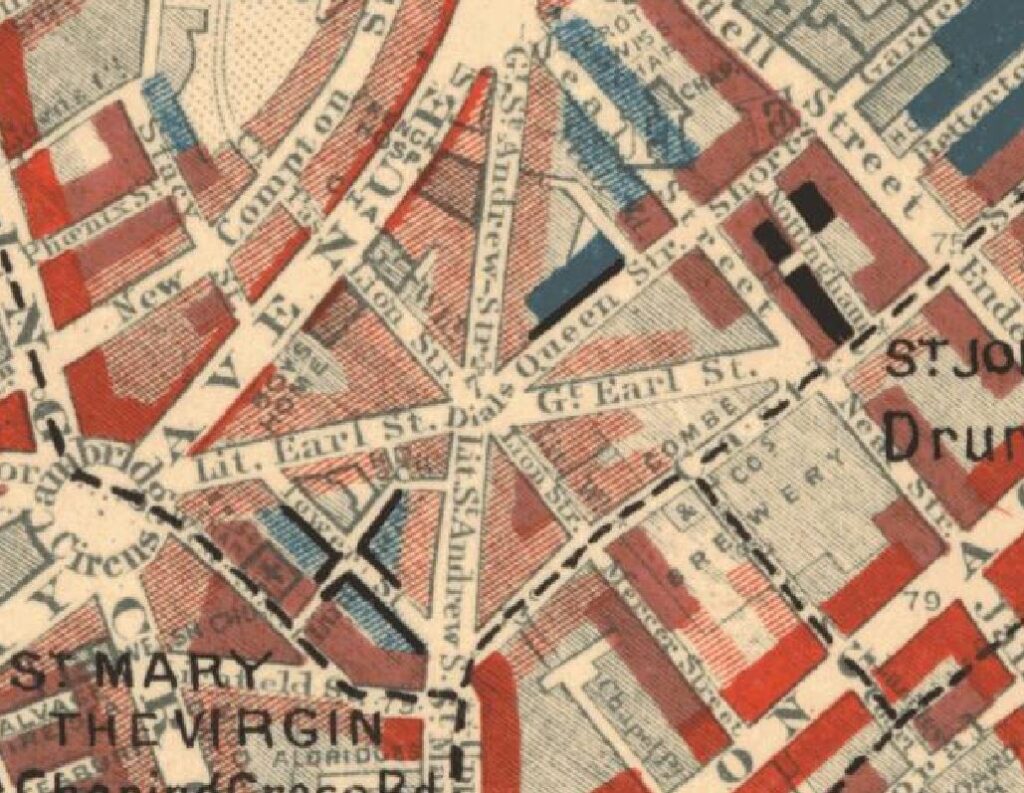

The layout of the streets around Seven Dials has not changed for a very long time. The 1895 Ordnance Survey map shows the same distinctive layout (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’):

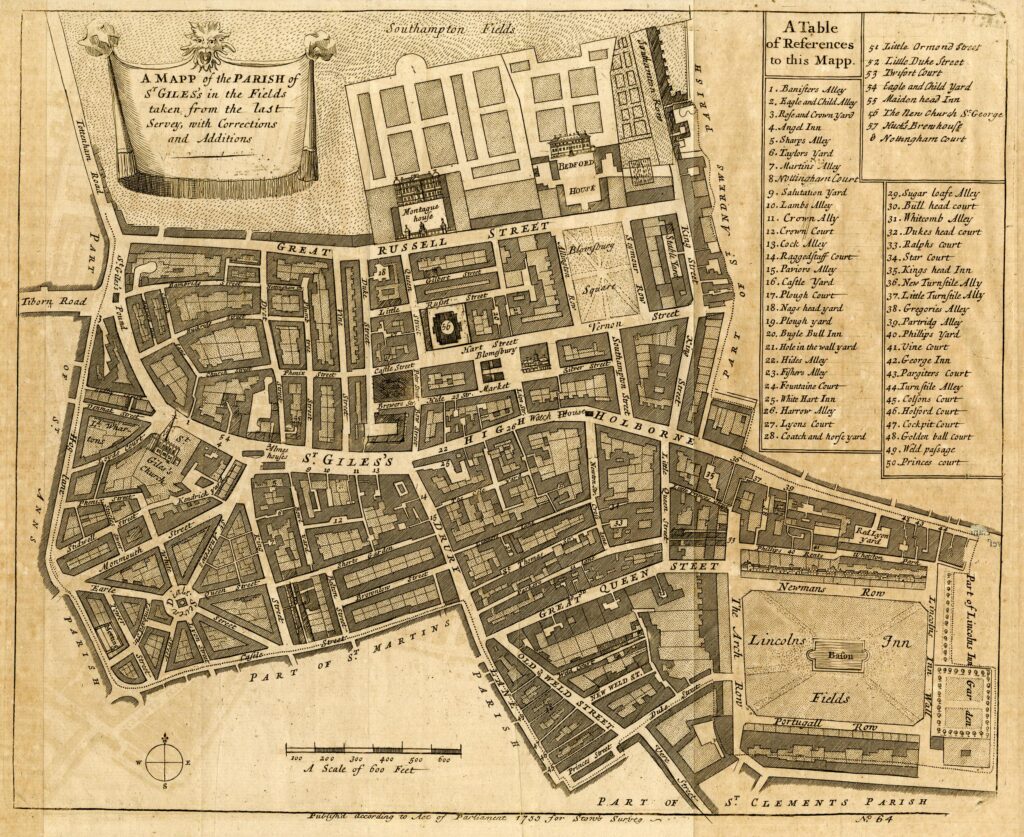

Going back to a 1755 map of the Parish of St Giles’s in the Fields, and the same distinctive layout is in the lower left corner:

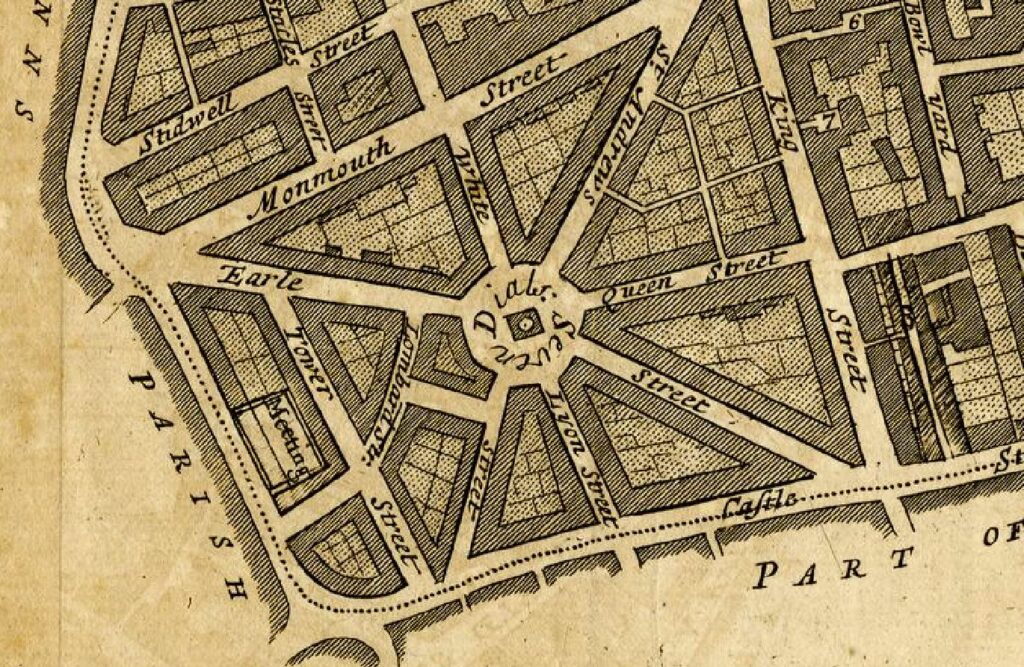

Detail of Seven Dials from the above map:

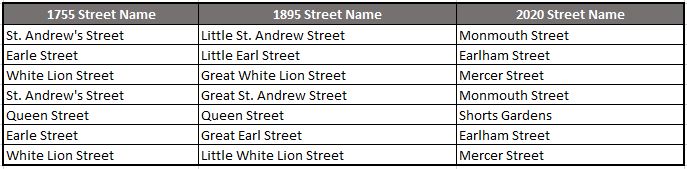

Comparison of the maps tells us a number of things about Seven Dials. Firstly the streets radiating out from the central junction have changed names over the years:

In 1755 the street name stayed the same as the street crossed the central junction, however by 1895 the names had been changed slightly to give each branch a distinctive name, so St. Andrew’s Street became Little and Great St. Andrew Street.

By 2020, the 1755 approach of extending the same street name across the junction had been put back in place, and a new set of names given.

When William Flegg was in Monmouth Street, he would have known the street as Little St. Andrew Street.

The maps also tell us something about the pillar in the centre of the junction. The 1755 map shows the pillar, however by 1895 the pillar had gone, and there was a Urinal in the junction. By 2020 the pillar was back in place.

I will come on to this later, however for now, lets take a walk along the southern section of Monmouth Street.

The terrace of houses with William Flegg’s premises in the centre:

Looking up Monmouth Street from the southern end of the street:

Buildings along the western side of Monmouth Street:

The rather magnificent Two Brewers pub, Monmouth Street:

The streets around Seven Dials are now full of clothing and jewelry shops, restaurants and cafes. Mainly small, one off shops rather than the large chain shops that can be found across much of London.

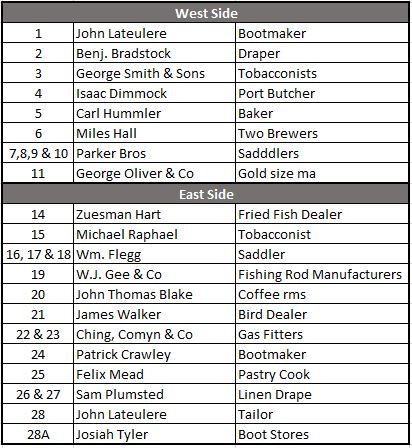

We can also walk through the street in 1895 and look at the businesses that occupied the houses by using the 1895 Post Office Directory.

We can see William Flegg occupying numbers 16, 17 and 18, so not just the single house with the sign on the wall. The numbers are different to today’s numbering as this was when this branch of Monmouth Street was Little St. Andrew Street.

The directory has a few abbreviations of which I have not yet found the meaning such as the “size ma” for George Oliver at number 11 and “rms” for John Thomas Blake at number 20.

This was a street of small manufacturers and traders, trading in everything from bread and meat to birds and fishing rods.

At the top of the southern branch of Monmouth Street is the Seven Dials junction, where the seven streets come together:

The streets running around the central Seven Dials junction were built during the later part of the 17th and early 18th centuries. Thomas Neale obtained the lease for the land in 1693. Prior to this, the area was already built-up, but with Cock and Pye Fields occupying the space where part of Earlham and Monmouth Streets now run.

In the following extract from William Morgan’s 1682 map of the city of London, I have marked the location of the central Seven Dials junction with a red circle.

There is only a single street that remains to this day. White Lion Street can be seen running through the red circle. This would stay White Lion Street when the central junction and seven streets where completed. Today White Lion Street is Mercer Street.

Note also that the street that would become Shaftesbury Avenue was Monmoth Street in 1682.

The central feature of the junction of the seven streets in Thomas Neale ‘s plans was a pillar.

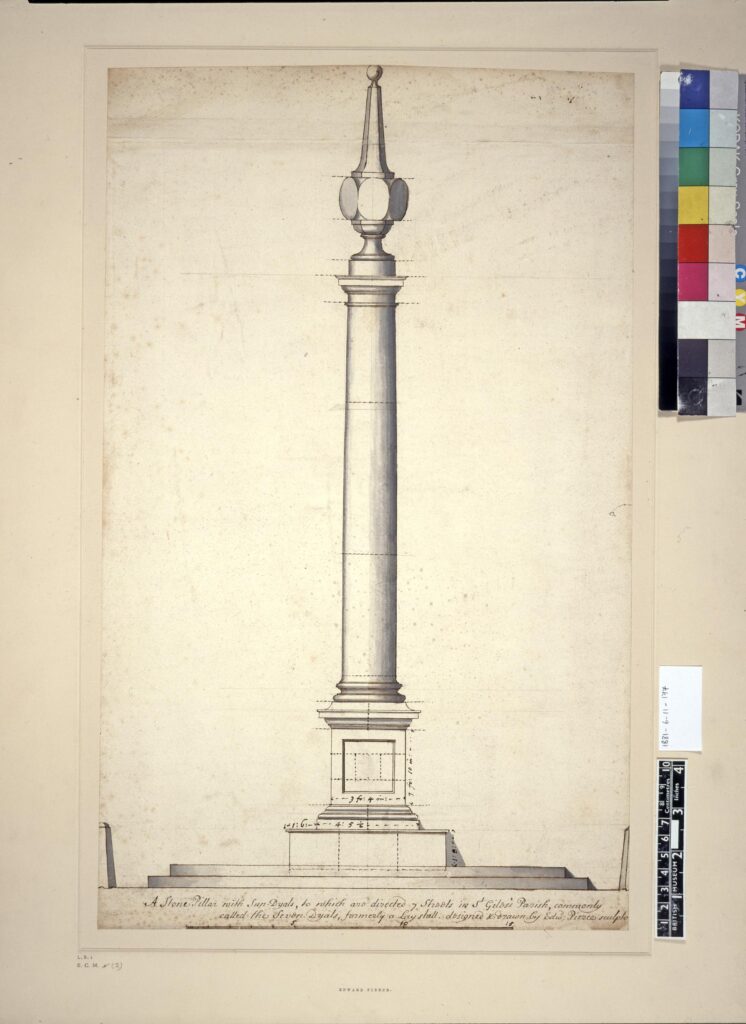

The British Museum has a copy of the original drawing of the pillar designed by Edward Pierce (©Trustees of the British Museum):

The text at the bottom of the drawing states “A Stone Pillar with Sun Dyals to which are directed 7 streets in St Giles’s Parish commonly called the Seven Dyals, formerly a Laystall”.

The word Laystall can refer to a place where rubbish or dung is deposited. It can also refer to a place where cattle are kept. This might be related to the location of the sun dial being at the entrance to Cock and Pye Fields in the 1682 Morgan map.

The 1895 Ordnanace Survey map shows the central junction without the pillar. It had been removed over 100 years earlier as it had become the focal point for so called undesirables and in 1773 the Paving Commissioners ordered the removal to prevent this nuisance.

The pillar eventually turned up in Weybridge, where the pillar, without sun dials, can be seen today at the junction of Monument Hill and Monument Green.

By the 1980s, the majority of Seven Dials was derelict, and there were plans for the demolition of the majority of buildings in the area. Restoration plans were proposed by the Seven Dials Monument Charity and fortunately this approach was supported, otherwise we would see a very different Seven Dials today.

There were efforts to bring the original pillar back from Weybridge, however the local council refused.

Architect A.D.Mason designed a new pillar based on the original design by Edward Pierce, which included making measurements of the original pillar in Weybridge. The new pillar and sun dials were unveiled on the 29th of June, 1989.

The new pillar would become the focal point for the restoration work of the streets surrounding the pillar, and the work has been a considerable success with the area packed with people in more normal times.

Looking down the southern branch of Monmouth Street from the central junction:

The Crown pub facing the central junction, between the northern branch of Monmouth Street and Short’s Gardens.

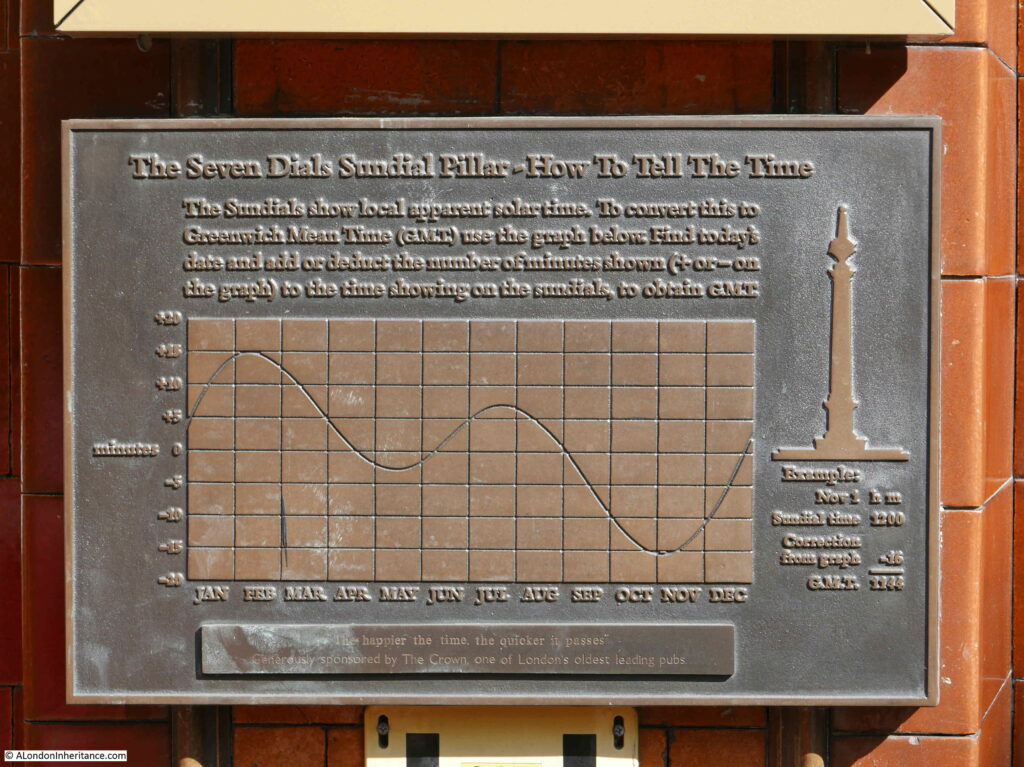

A plaque on the pub shows how the solar time shown by the pillar can be converted to Greenwich Mean Time:

The new central pillar:

The Cambridge Theatre (opened on the 4th September 1930), between Earlham and Mercer Streets:

The Crown pub, then Short’s Gardens, then Earlham Street:

During the first decades of the 1700s, the new area of Seven Dials quickly become a reference point for news reports and a sample of reports between the years 1723 and 1749 tells us much about life in these brand new streets:

21st March 1723: There is just finished by Mr John Noble, living near Seven Dials, an Organ, which by using bellows only, without the help of an Organist, sounds several Tunes to Perfection.

6th February 1725: One Murphy, a Centinel in the 2nd Regiment of Guards, was on Saturday last seized near the Seven Dials, on Suspicion of being concerned in the robbing of the Chester Mail. One of the Chester Bags (out of which letters were stolen) having been found near a hedge, was brought to the General Post-Office yesterday morning.

1st November 1729: Late last night one Welch, who buys and sells old Cloths, was set upon by two Street-Robbers at the Corner of St Andrew’s-Street, near the Seven Dials, who took from him in Cloths and Money to the value of seven pounds and upwards.

There was a pillory at the Seven Dials in the early decades of the 18th century, and the risks of being sentenced to the Pillory can be seen from the following newspaper report:

22nd June 1732: Last night, the Coroner’s Inquest upon the body of John Waller, who stood in the Pillory at the Seven Dials in the Parish of St. Giles’s in the Fields last Tuesday, and brought in the Verdict wilful murder with unlawful weapons.

Later in 1732, the person who had killed John Waller was included in a list of those sentenced to death, but the report does not provide any background as to why he was murdered:

14th September 1732: Richard Griffith, for being concerned in the Death of Waller who was killed in the Pillory at Seven Dials.

24th November 1733: Last Saturday Mr Rambert, a Coal Merchant in Tower Street, near the Seven Dials, received an Incendiary Letter threatening to set his House on Fire, and kill him, if he did not leave twelve Guinieas in a certain place mentioned in the letter, which was written in French. That night Mr Rambert left twelve Half-pence in the Place, and at about One in the morning, some Neighbours who watched to see the consequence, observed four fellows pass by, when one of them took up the half pence and walked off with the imaginary prize. We hear nothing however of their being pursued.

Strangely, 16 years later, there is a report of someone being arrested for writing incendiary letters:

24th November 1749: On Saturday night, one Franks, a shoemaker, was taken at a house near Seven Dials, on the Oaths of his Accomplices, for writing Incendiary Letters to several persons, in order to extort Money thereby.

People living in the streets leading off from the Seven Dials pillar could be very wealthy:

15th October 1741: On Saturday last died at his House in Earl-street, near the Seven Dials, Mr. Philips, a Distiller, said to have died worth 30,000 pounds, and on Thursday Morning his Corpse was carried out of Town, in order to be interred near his deceased relations, about three miles from Nottingham.

29th November 1744: The same day, Hannah Moses, otherwise Samuel, the Widow of one of the three Jews who were hanged about three sessions ago, was committed by the same Gentleman to New-prison, and her accomplice, Benjamin David Woolf, to Newgate, for stealing out of the shop of Mr John Barber, a Silversmith, at the Seven Dials, an Ingot of Silver.

19th May 1749: A few days since a Sailor went into a Chandler’s Shop in Earl-street, near the Seven Dials, to ask for a Lodging; but the man telling him there was none to let, he asked for a Halfpenny-worth of Tobacco, which as the Shop-keeper was serving, he drew his Hanger, cut him down behind the Counter, and made off; and yesterday the unfortunate man died of the wounds he received.

25th August 1749: Two Sawyers belonging to Mr Neale’s Yard in King’s-Street, Seven Dials, quarreled and fought, and one of them, by a fall, fractured his skull and died immediately, and the other being carried before a Magistrate, was by him committed o New-prison, Clerkenwell.

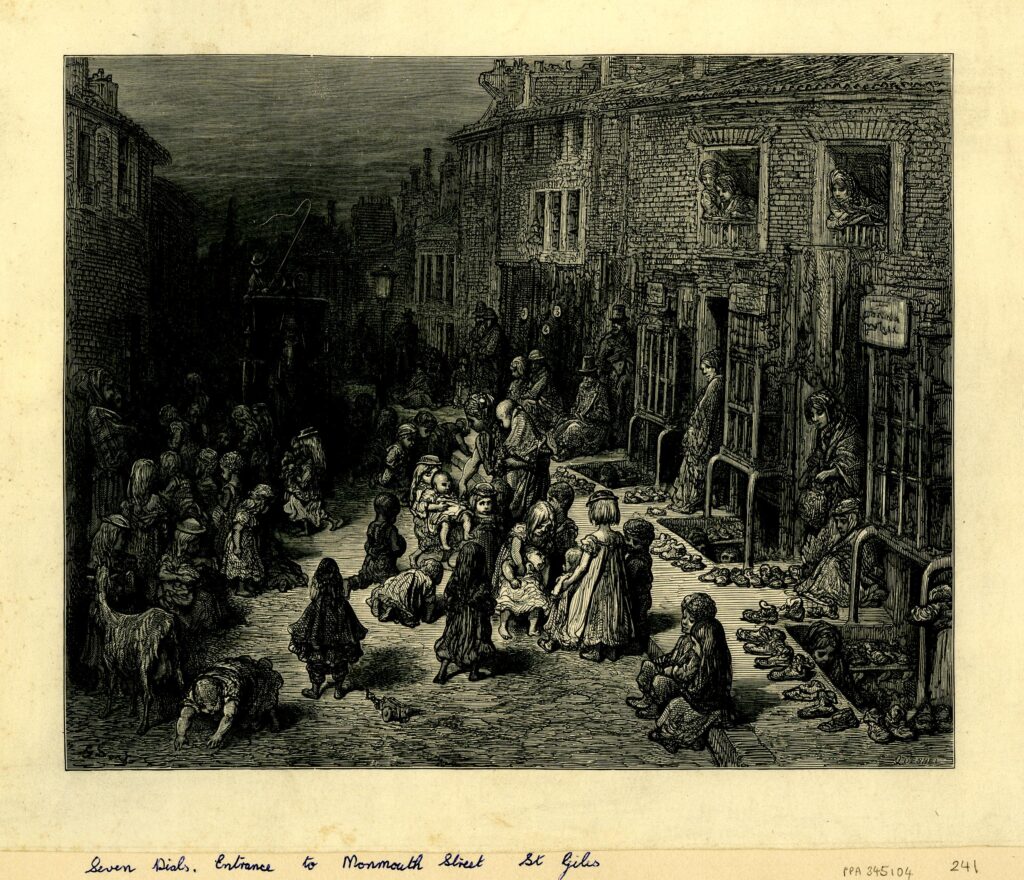

By the late 19th century, many of the streets around Seven Dials were crowded, with many poor occupants. Gustave Dore drew the entrance to Monmouth Street from Seven Dials. People crowd the street, shops and basements with shoes for sale line the side of the street and children play in street, blocking the path of a carriage (©Trustees of the British Museum).

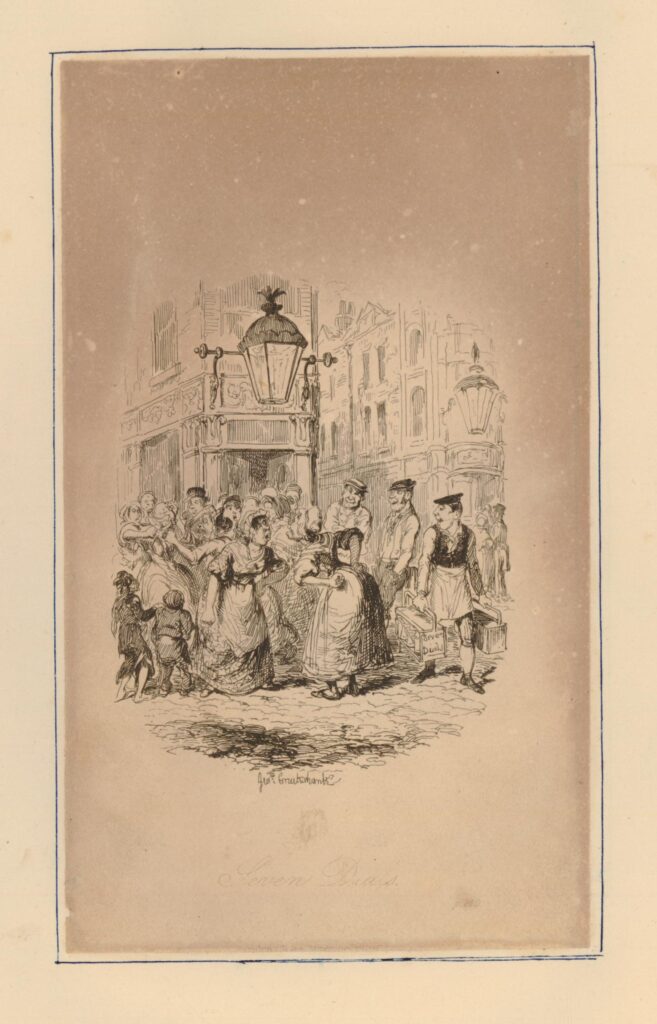

George Cruikshank had earlier produced a drawing around 1836 as an illustration to Charles Dickens’s Sketches by Boz. The drawing shows two women being urged to fight in front of a gin palace in Seven Dials (©Trustees of the British Museum):

Despite the impression created by Gustave Dore, Charles Booth’s poverty map of London, between 1898 and 1899 shows most of the streets around Seven Dials as “Fairly comfortable. Good ordinary earnings”, although the dark blue along Queen Street is classed as “Very poor, casual. Chronic want”.

The following photo from the 1897 publication “The Queen’s London” shows a street leading up to the Seven Dials junction. The photo gives a different impression of the area to that of Gustave Dore’s drawing.

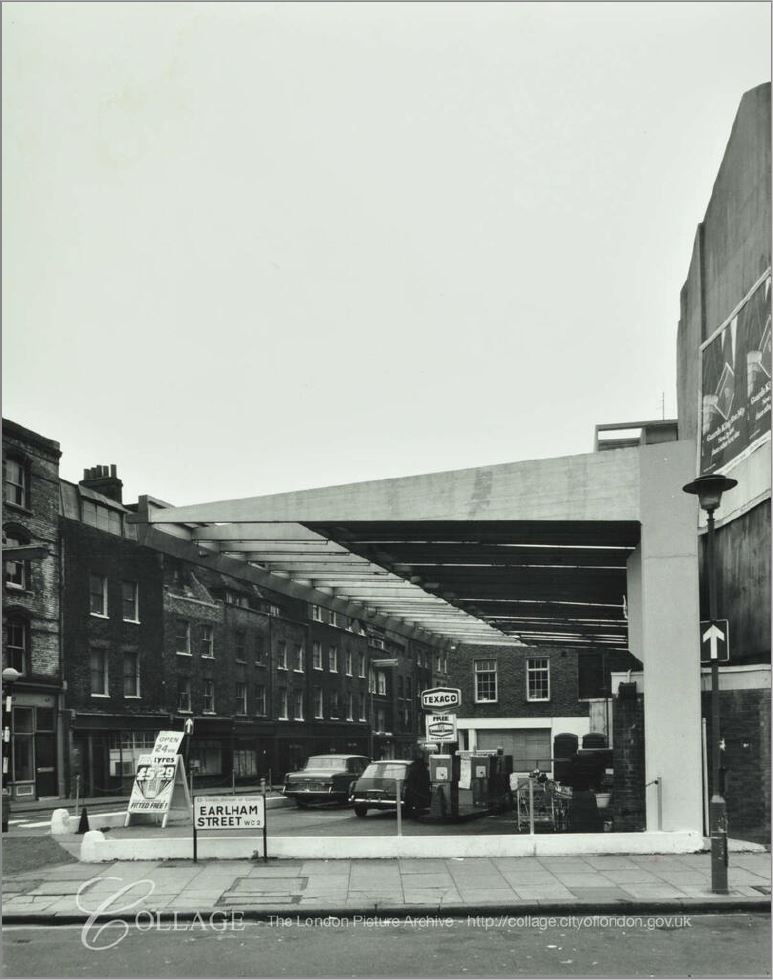

By the 1970s, the area was very much in decline. The streets were all open to traffic, there was no central pillar and cars would pass across the central junction between streets. Some of the space in the streets was used for purposes that seem very strange when looking at the area today.

In 1974, a Texaco petrol station occupied the space between Earlham and Monmouth Streets. This is the space to the right of my earlier photo looking down the southern branch of Monmouth Street from the central junction,

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_152_74_21025

There is much to discover in the streets that lead off from the central junction of Seven Dials. I have only covered the southern branch of Monmouth Street and a general history of area. It would take a very much longer post to cover the whole area.

There are a couple of houses in the southern section of Mercer Street that I want to show. They are a pair of late 17th century terrace houses that date from the original construction of Seven Dials. This is number 27 Mercer Street:

And number 25. Both are Grade II listed.

The view looking up Mercer Street towards the pillar from the junction with Shelton Street:

During the summer and autumn period, many of the streets have been closed, providing more space for pedestrians and the cafes in the area.

Seven Dials is usually very busy. Tourists, visitors to London, those visiting the theatres and restaurants of the West End add to those who live and work in the area.

in the run-up to Christmas, the streets around Seven Dials are crowded, and a couple of years ago I photographed a Saturday evening around Seven Dials. Here are three examples.

Looking up Monmouth Street towards the central junction:

Around the central pillar:

Crowds and the Cambridge Theatre:

Many of the buildings of Seven Dials have been redeveloped, and the original pillar is now to be found in Weybridge, but the general layout is still the same, and some of the original buildings survive.

I suspect that Thomas Neale would be rather pleased that his Seven Dials development is still here 300 years later.