If you walk out of London Bridge Station into Tooley Street, walk west up towards London Bridge, you will see a memorial to a fireman who died during what was described as the Great Fire at London Bridge in 1861 (also known as the Great Fire in Tooley Street), when a considerable number of the warehouses between Tooley Street and the River Thames were destroyed, alongside millions of pounds worth of goods.

Chances are that you will miss the memorial, installed on the first floor corner, along the side of a building facing on to Tooley Street. Although the lane alongside the building is now gated, it is called Cottons Lane, a name relevant to the warehouses destroyed in the fire.

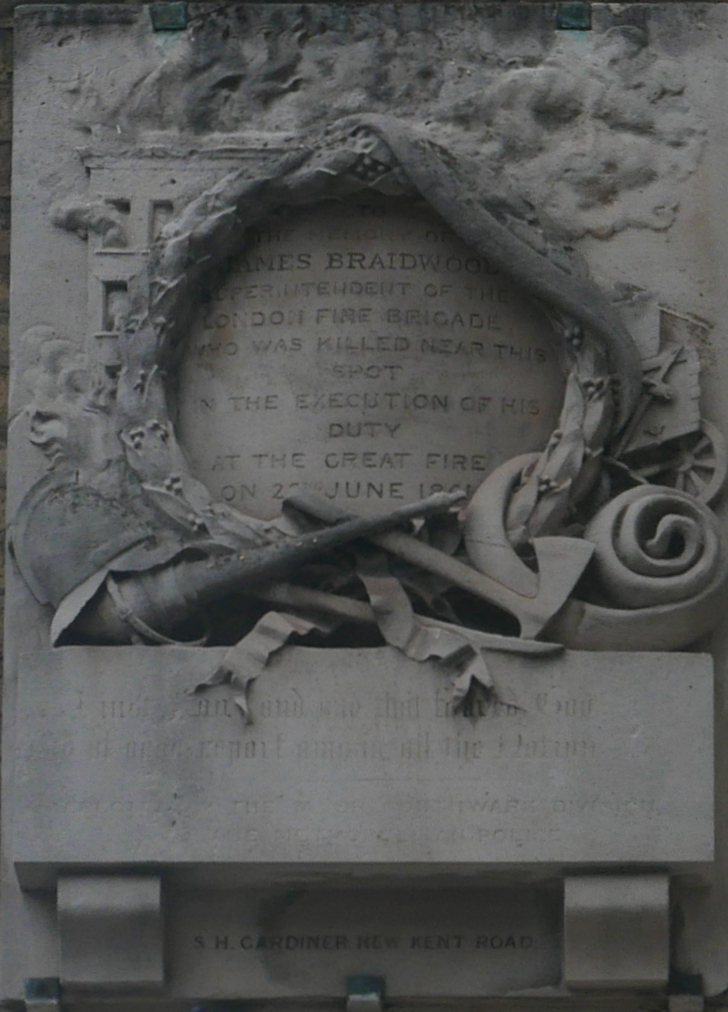

Although the words on the memorial are difficult to read, it really does deserve a closer look. It records the death of James Braidwood, Superintendent of the London Fire Brigade who “was killed near this spot on the execution of his duty at the great fire”. These details are in the centre of the memorial, surrounded by a wreath.

Around the wreath are some details of the fire brigades profession, along with an image of the Great Fire at London Bridge.

At bottom left is a fireman’s helmet, sitting on the end of a nozzle through which jets of water were directed. To the right is an axe, followed by a water hose. Above this is the wheel of a fire engine.

At top left is a burning warehouse, with flames and smoke covering the top of the monument.

The fire that the memorial records, broke out on Saturday 22nd of June 1861. It would burn for days, destroy many warehouses and cause millions of pounds worth of damage and loss.

The following newspaper report provides a good indication of the scale of the fire:

“DREADFUL CONFLAGRATION IN LONDON. UPWARDS OF TWO MILLIONS’ LOSS – The metropolis on Saturday evening was visited by one of the most terrific conflagrations that has probably occurred since the great fire of London. Certainly for the amount of property destroyed, nothing like it has been experienced during the last half century.

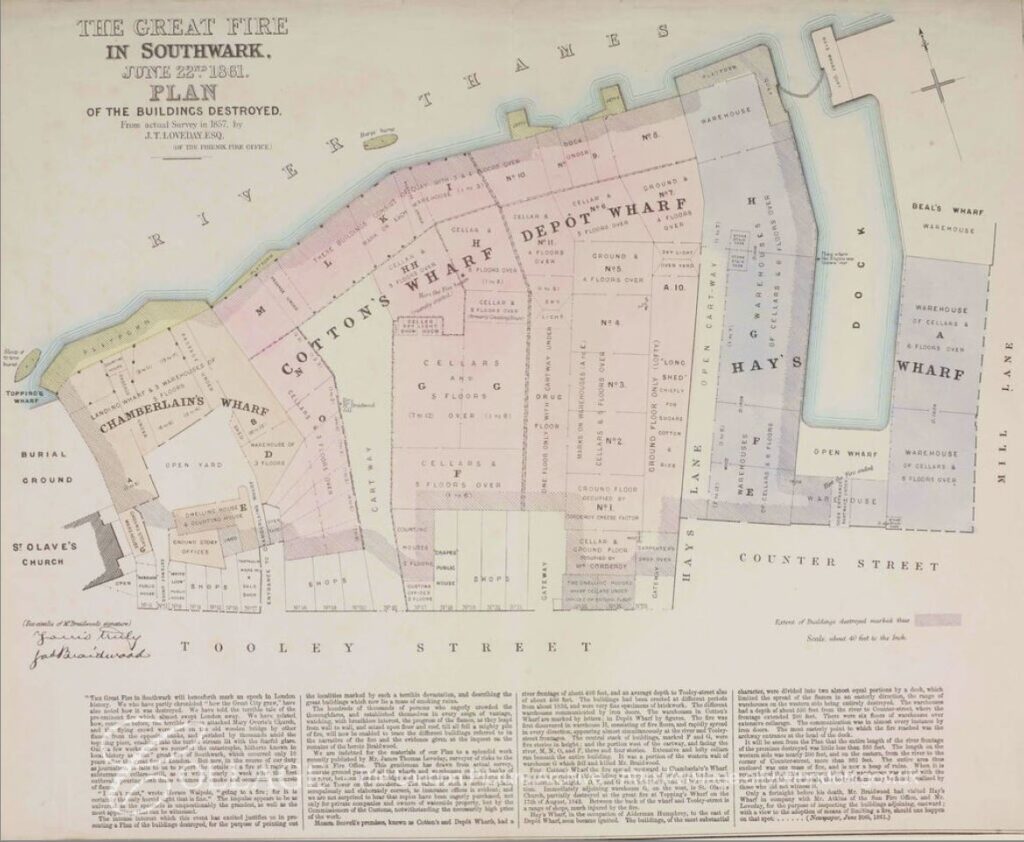

The scene of the catastrophe was on the water side portion of Tooley-street, nearest London bridge, a locality which has been singularly unfortunate during the last 25 years, some of the largest fires having occurred here. The outbreak took place in the extensive range of premises known as Cotton’s Wharf and the bonded warehouses belonging to Messrs. Scovell.

They had an extensive river frontage, and the whole place on the land side extending to Tooley-street was covered with eight or nine warehouses six stories in height, some of which had formerly been used as ordnance stores, and the whole occupying, as we were informed, about three acres.

These buildings were filled with valuable merchandise of every description. There were some thousands of chests of tea and bales of silk stored in the upper floors, while in the lower was an immense stock of Russian tallow and tar, oils, bales of cotton, hops and grain. Every portion of the establishment might be said to have been loaded with goods, and of the whole of this property, not a vestige remains but the bare walls and an immense chasm of fire, which at dusk on Sunday evening still lighted up the Pool and the east end of the City.

To be added to this very serious loss is the destruction of the whole of the western range of Alderman Humphrey’s warehouses flanking the new dock, known as Hay’s Wharf, the burning of four warehouses comprising Chamberlain’s Wharf, adjacent to St Olave’s Church, besides many other buildings in Tooley-street”.

Smaller fires were a frequent hazard in the warehouses lining the Thames. The article extract above lists some of the goods stored in the warehouses. All very inflammable, and it had been a hot summer with little rain, so the buildings and their contents were dry and ready to burn.

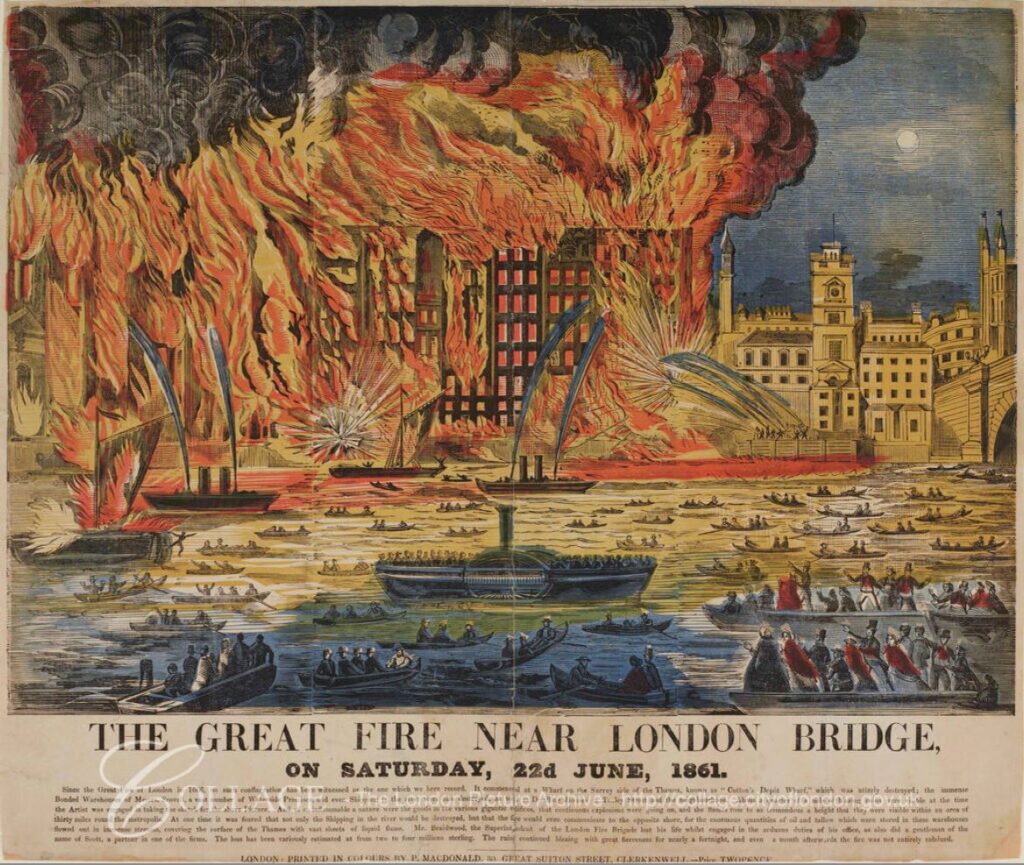

The following print from the time gives an impression of the scale and ferocity of the fire. The southern tip of London Bridge can just be seen on the right edge of the print.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: p5354642

As well as the size of the fire, the print shows some of the fire fighting methods of the time. On the river are two steam powered fire boats. This method of firefighting was essential in London due to the number and size of the warehouses hard up against the river. It was frequently only possible to fight a fire from the river. One issue facing the fire boats at the London Bridge fire when they arrived was a very low tide. This prevented them getting close to the warehouses and drawing sufficient water. It was only when the tide came in that the height of water in the river was sufficient for the fire boats to be effective.

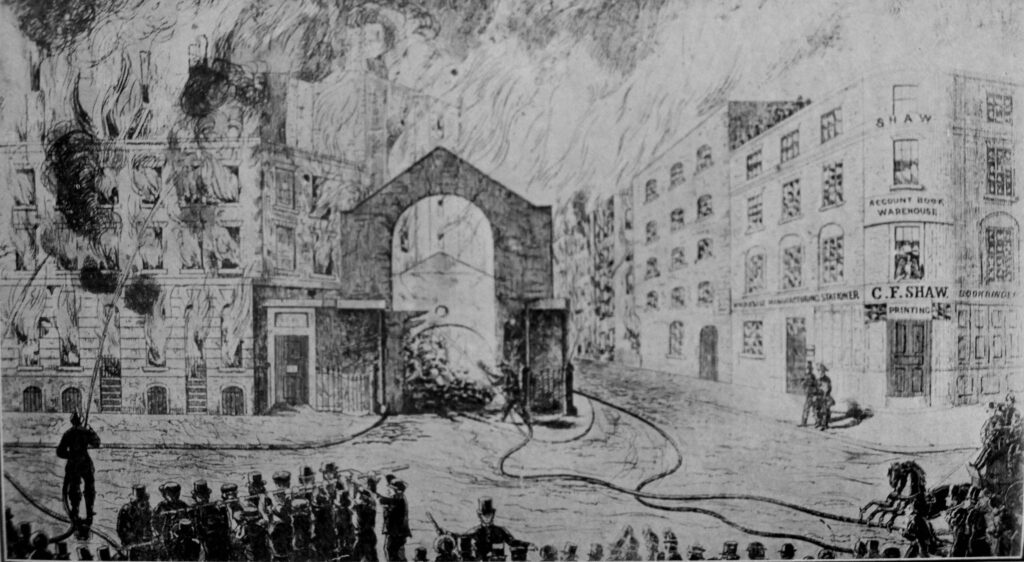

To the right of the fire, a cluster of firefighters can be seen in front of the large building at the end of London Bridge. They are directing their hoses on the western edge of the fire.

The river is full of boats carrying spectators, and I suspect the watermen of the river found it very profitable to give people a close up view of the fire, although this could be dangerous. Look at the larger boat on the left edge of the print. A fire has started on the boat, and a figure is seen jumping into the river from the boat.

Fires were almost entertainment events for Londoners, who lined London Bridge and filled the many boats on the river at all hours of the day and night. The following newspaper extract illustrates how the fire spread and the onlookers responses:

“While Chamberlain’s Wharf was in full blaze it was feared by many that St Olave’s Church and Topping’s Wharf would follow, but fortunately, a vacant piece of ground interposed, which no doubt saved both. On the other hand, Hay’s Wharf, it became evident, had caught fire in the roof, through which clouds of smoke and sharp spires of flame were darting. The iron shutters for a long time kept in the fire here, except at intervals when it forced its way upwards; it must have been at least an hour after the top floor was blazing before the fire descended to the floor below. After that the other floors followed. When Hay’s Wharf was included the river sweep of the conflagration must have been 300 yards, with a deep foreground of blazing oil and tallow. The higher the tide rose the wider became the sheet of flame, as cask after cask of tallow melted and rolled, liquidwise, into the Thames.

As the tide rose attention became fixed upon the dock at the end of Hay’s Wharf, for the spectators were anxious upon two points – first, they wished to see if there was a possibility of escape of the two vessels lying there, close to the walls of the fire proof, but fire filled buildings; and secondly, they feared that the fire would leap the narrow chasm of the dock and seize on Beal’s Wharf, and then, as must have happened, burn down a great extent of wharfage property beyond. After midnight, when the water had risen sufficiently high, the screw steamer was towed out amid the cheers of the onlookers, and ten minutes later two tugs drew out an American barque, just as the iron shutters of the building fell out of the side next to the dock, and the conflagration shot forth its fiery tongues”.

The following print of the fire shows the masts of one of the ships that were rescued from the fire. They can be seen on the left of the print, with the flames of the burning warehouses getting dangerously close.

The following plan shows the buildings destroyed in the fire:

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: p5354659

The fire as viewed from Tooley Street:

There were a number of casualties during the fire. Five men who were in a boat collecting tallow floating on the river were either burnt to death or drowned when their boat caught fire. A number of men working in the area of the warehouses fell into the river and drowned.

Those suffering burns were taken to St Thomas’s Hospital, which also included a man who had his neck broken when the chain from a fire boat was caught around his neck.

Many of the boats on the river were collecting goods that had fallen out of the warehouses which they then sold for profit. Papers also reported that numerous mudlarks were out on the river foreshore using old sacks, saucepans, baskets, anything they could use to hold the goods from the warehouses being washed up on the shore.

The fire also brought out the worst in human behavior with groups of pickpockets making their way among the crowds watching the fire. Twenty four pickpockets were caught and taken to Mansion House for immediate judgement.

The memorial in Tooley Street records the name of the most high profile casualty – Mr James Braidwood of the London Fire Brigade.

Braidwood was the Superintendent of the London Fire Brigade and had many years of experience. The following report details the circumstances of his death, whilst he was visiting the individual groups of fire fighters in among the warehouses:

“Mr Braidwood, who had visited the men several times, was engaged in giving them some refreshment, when, all of a sudden, a terrific explosion occurred. In an instant it was seen that the whole frontage of the second warehouse was coming down, falling outwards into the avenue. Mr Henderson, the foreman of the southern district of the brigade, who was standing within a few paces of Mr Braidwood, shouted for all to run. The men dropped their hose branches. Two, with Mr Henderson escaped by the front gateway, and the others ran in the opposite direction on to the wharf where they jumped into the river. Mr Braidwood made an effort to follow Mr Henderson, but was struck down by the upper part of the wall, and buried beneath some tons of brickwork. His death must have been instantaneous. Several of his men rushed to extricate him, hopeless as the task was, but another explosion happening, they were compelled to fly. The sad fate of their chief had a most depressing effect upon all, and, to add to their trouble, the conflagration now assumed a most awful ascendancy”.

James Braidwood played a key part in establishing the London Fire Brigade. Born in Edinburgh in 1800, he was appointed superintendent of the Edinburgh fire brigade at the age of 23, and quickly gained a reputation for increasing the efficiency of the fire service in Edinburgh. In 1830 he published “On Construction of Fire-Engines and Apparatus, the Training of Firemen and the method of proceeding in the Cases of Fire”. In London at the time, the fire service was still run by individual insurance companies. This often resulted in a fire engine arriving at a fire, determining that the building was not insured by their company, and turning around.

Braidwood’s publication gained the attention of London’s insurance companies, and in 1832 he was appointed to the supreme command of the embryonic London Fire Brigade.

He initially had to overcome the prejudices and dislike of innovation from the London firemen, but gained their support and trust when they could see the benefits of the changes he put in place.

London’s fire service was very small for a city of such size and complexity, with numerous warehouses full of combustible goods. For comparison, Braidwood took on a force with 120 firemen, when at the same time, Paris had a force of one thousand trained firemen, and numerous fire appliances.

One of Braidwood’s innovative methods was his approach to fire prevention. He took an active part in advising owners of buildings how to implement precautions against fires.

He was also known for acts of bravery. In a fire in Edinburgh where barrels of gunpowder were stored in a burning building, he went in alone and carried each barrel out after having wrapped the barrels in wet blankets. In London he rescued a child from a burning building, having to walk across a plank to the room where the child was, and return via the same route.

He left a widow and six children. His wife had already suffered a similar bereavement, as a son from a previous marriage had died fighting a fire in Blackfriars Road in 1855.

His funeral took place at Abney Park Cemetery. The funeral procession was almost a mile and a half in length, and as well as the London Fire Brigade, there were members of the City and Metropolitan Police forces, members of the remaining private fire-brigades, along with many prominent persons of mid Victorian London.

The memorial in Tooley Street was installed in March 1862. I suspect it was in a more prominent place than now, as when installed it was on the west wall of a building on Tooley Street. Today it is on the eastern side of the building.

As well as the memorial, a short distance east there is a Braidwood Street, also to commemorate James Braidwood:

The inquest into the death of James Braidwood reached a conclusion of accidental death.

The jury at the inquest heard that he had been in among his fire fighters handing out brandy and encouragement when the wall fell on him, killing him instantly.

The inquest recorded the enormous quantities of goods held in the warehouses, the majority of which were highly inflammable, including a considerable quantity of salt peter, which is the natural mineral form of potassium nitrate. Among its many uses, it is the principal ingredient in gunpowder, and as an oxidizer for fireworks and rockets. Having such an explosive chemical stored in such large quantities in a very busy warehouse complex in the centre of London shows the complete lack of any regulations at the time for the safe storage of such materials.

The area between Tooley Street and the river were still smoldering two weeks after the start of the fire. Over 200 police were employed to stop the public trying to get into the area. The fire brigade were kept busy pulling down dangerous walls and getting access to the burning vaults.

The area was though, quickly rebuilt and by the time of the 1893 Ordnance Survey map, the area is again full of warehouses. Hay’s Wharf was rebuilt, and it is the post 1861 fire version of Hay’s Wharf that we see today. ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’

If you find yourself in Tooley Street, glance up at the memorial to remember the Great Fire at London Bridge and the Superintendent of the London Fire Brigade, Mr James Braidwood.