For just over a week, the blog has had a fault connecting with the subscriptions package, so although I wrote a new post last Sunday, it appeared on the blog, but did not get e-mailed out. The connection has been rather unstable for the last few days, but now looks better, so I hope the problem is fixed. To test, here is a post with the strange story of when Willesden was the centre of oil exploration in London.

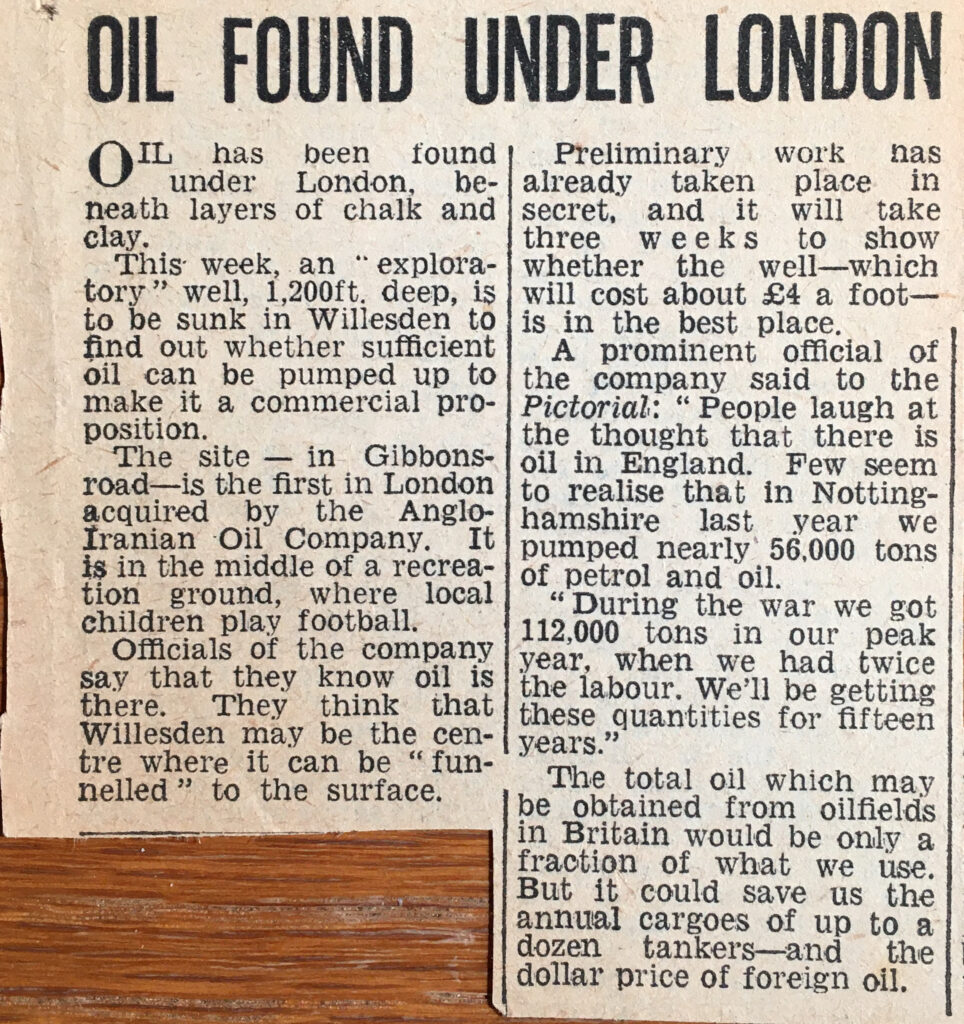

I have mentioned before one of my fascinations with old books is that you never know what previous owners may have added between the pages. I was looking through a copy of Haunted England by Christina Hole (1941 – A Survey of English Ghost-Lore), and between the pages were a couple of clippings from newspapers about an oil well that was drilled in Willesden in 1947:

After the war, the country was desperate for foreign currency, and was trying to export as much as possible, as well as to limit any imports that would have to be paid for in a foreign currency, such as dollars.

One of the major dollar imports was oil and as the article mentions, any source of oil that would enable a reduction in imports would have been highly important to the economy.

The fact that there were traces of oil deep below the streets of Willesden had been known for a number of years. In 1911 a laundry business in Willesden had been drilling a borehole as a water source, but instead found traces of oil. This resulted in a search for oil by drilling the borehole much deeper to see if there might be commercial quantities available, as reported in the Pall Mall Gazette:

“Is oil present in paying quantities in Great Britain? Is this country to be to some slight extent independent of its coal measures?

That is an interesting question which, often mooted before, is prompted again by the recent announcements that oil had been discovered in a well-boring at the White Heather Laundry, Willesden. In the days when ‘booms’ are only too readily created, the owners of the Willesden property showed commendable reticence in refraining from making public their discovery until the news leaked out through a channel which has not yet been discovered.

It must be remembered that the oil obtained at Willesden so far only amounts to a very small quantity, and the question whether it is there in commercial quantity is not likely to be settled for some time; the boring was started in January, 1911, and the first indication of oil was obtained at a depth of 1,200ft on September 6th. The depth of the boring is now 1,735ft. The people concerned are now definitely ‘going for oil’ and the success or failure of their experiment will be watched with absorbing interest”.

There were further positive news reports including:

“One of the directors of the laundry (which was founded about ten years ago by four young men from Cambridge) said: ‘We have had several members of City companies up here already, including representatives of the Standard Oil Company. We had found a splendid quality of water at a depth of 1,000ft, but the quantity is short of our requirements, and that is the chief reason why we are going deeper. We prefer to test the real value of the oil discovery before making any sort of deal”.

The borehole found very salty water at a depth of 1600ft, which was assumed to be water from an old sea formation.

Water was rising to the top of the borehole, and variable amounts of gas would also bubble up through the water.

The 1911 borehole did find traces of oil deep below Willesden, but not sufficient quantities to be economically viable, so the “four young men from Cambridge” did not make their fortune from oil.

Another attempt at finding oil was the 1947 borehole in the article at the start of the post. It may well be that the need to restrict imports encouraged another attempt at finding oil after the failure of the 1911 borehole.

The 1947 borehole was drilled by the D’Arcy Exploration Co. Ltd, a subsidiary of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. This was the oil company that was formerly known as the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, which was the first oil company to extract oil in Iran. The company would later become British Petroleum (BP), so this new exploration in Willesden was being undertaken by a company with some serious oil exploration heritage.

The cost for drilling the borehole and examining the results came to a total budget of £10,000, a considerable sum for such a speculative undertaking.

Expectations were high, and the planned borehole made the national press with the Daily Mirror reporting that there was a strong possibility of oil being found, and that “One of the officials on the site yesterday said ‘I think the prospects are good’ “.

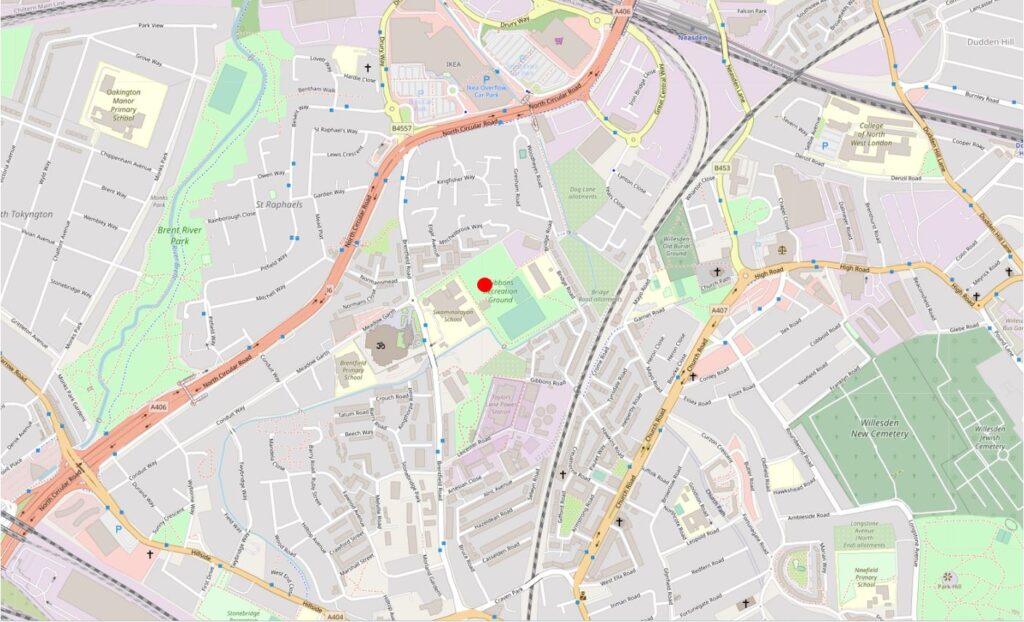

Work on the borehole commenced in November 1947, with even the serious Illustrated London News stating that “North London could become another Kirkuk” (the city in Iraq that was producing 4 million tons of oil a year before the war). The borehole was being drilled in the Gibbons Road Recreation Ground, an area of open space we can still find today. In the following map extract, a red circle marks the approximate location of the borehole (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

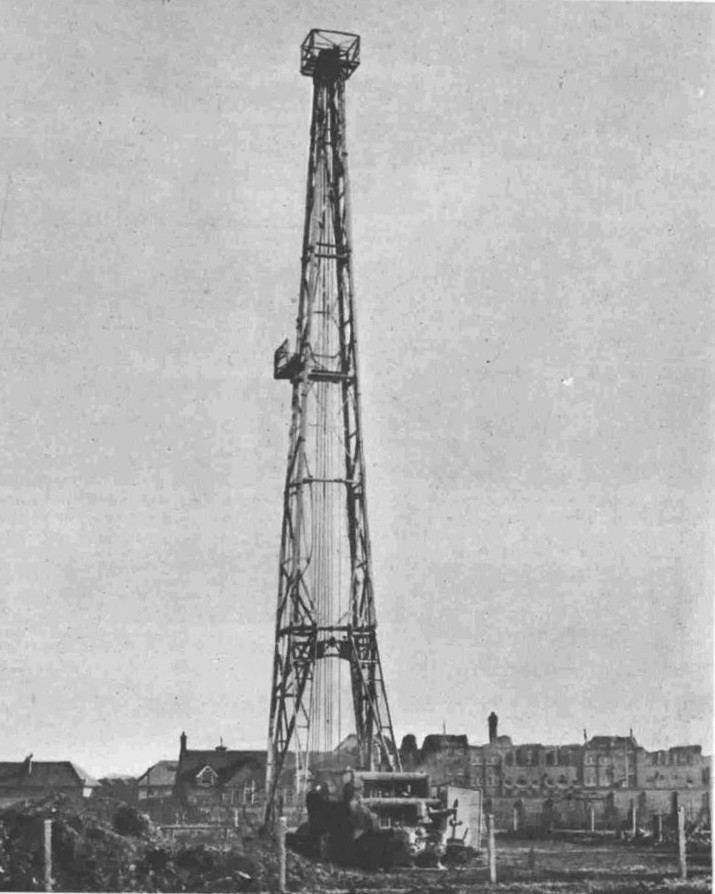

An 87 foot high “jack-knife” derrick was used, powered by a Caterpillar diesel engine. The following photo gives an impression of the derrick in operation:

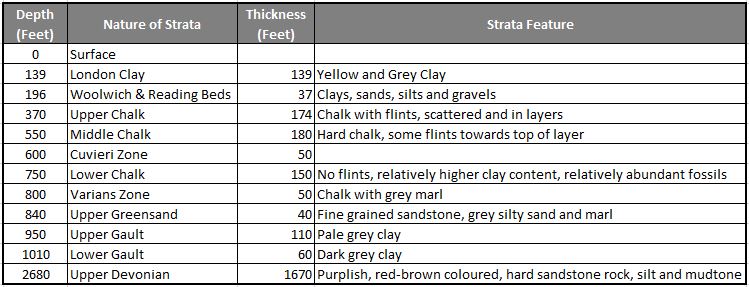

The borehole went down to the remarkable depth of 2,680ft, and the original bore hole logs by the D’Arcy Exploration Company can still be found online. The British Geological Survey has an online portal which maps all the boreholes that have been notified to them, and clicking on each borehole location will identify if the logs are online with a link for access (see link at the end of the post).

It is remarkable how many boreholes there are across London, and it is fascinating to look for patterns in their locations on the British Geological Survey site.

The borehole log for Willesden reveals the following rock strata as the drill headed 2,680ft below the surface of London.

The log pages reveal interesting details of what was found at different levels.

Pyrolised wood was found at about 60 feet (pyrolised refers to the decay of wood in the prescence of heat).

The Cuvieri Zone seems to refer to a zone where a specific type of plankton fossil called Orbulina was found.

A fractured zone with fish remains was found at a depth of 1085 feet.

Although trace amounts of oil were found, it was clear that Willesden would never be an oil producing area, and drilling of the borehole ended in January 1948. The borehole record contains the single word “Abandoned” at the end of the list of strata.

The borehole was capped, and concrete was used to fill the hole from a depth of 1000 feet to the surface – strange to think that this long concrete column now sits below Gibbons Road Recreation Ground – for comparison, roughly the same height as the Shard, and the overall borehole drilled down two and half times the height of the Shard.

Drilling had been met with an air of excitement in newspaper reports at the start of work, however by January 1948, the only reports were a small paragraph stating “Experts have abandoned hope of striking oil at Willesden, but work will continue to obtain general geological information”.

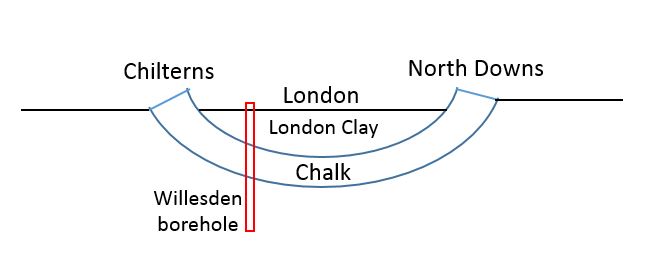

The geology of London is fascinating. In the Willesden borehole, thick layers of chalk were found. These form a sort of bowl underneath the city, curving below the city, rising up to form the Chilterns to the north of the city, and North Downs to the south.

The following graphic shows how the chalk layer dives under the city. The Willesden borehole drilled through London Clay and Chalk layers to the much older rocks below.

London Clay formed as a sediment at the bottom of a sea, formed around 56 to 34 million years ago. The chalk layers are much older and also built up on the bottom of a warm sea in the Cretaceous period over 65 million years ago.

The geology of London goes some way to explaining why there are far more Underground train routes north of the river than to the south. London Clay is a relatively easy substance to tunnel through, and although I have shown it equally spaced in the above graphic, in reality there is far more London Clay to the north of the river than the south.

London Clay is impermeable – water does not easily pass through the clay, chalk is permeable and explains why boreholes such as the 1911 borehole for the Willesden Laundry, were sunk to access water. Rain from outside the area of London Clay would flow through the chalk and water would collect in the layers of chalk under the city.

The British Geological Survey map of boreholes provides so much information on the geology below London. The chalk layer has provided London with water for centuries. The record for a borehole at 1 Bankside, performed in the late 19th century for the Belfast and London Aerated Water Company identified a minumum water flow of 3,000 gallons an hour. Water was found at a depth of 114.5 feet. The purity of the water was measured at 27.1 parts per 100,000 of total solids, or which 12.7 were Chlorine.

A note at the bottom of the borehole record states that the site was visited on the 11th July 1946 and that the borehole had not been filled in, but was boarded over and had not been used for some 30 to 40 years. The note remarked that the borehole probably could not be used anymore due to dirt and rubbish.

St Paul’s Catherdral sits on a hill, however in the distant past water has washed over this area. A 2008 borehole at One New Change identified a 6m thickness of River Deposits below the built layer near the surface. this layer consisted of dry sand and gravel for the first 4.5m, followed by a 1.5m layer of wet sandy gravel.

This may all seem rather remote as we walk the streets of London, however the strata below the surface impacts the location and design of so much of the infrastructure we take for granted.

For example, with the extension of the DLR from the Isle of Dogs to Greenwich and Lewisham a detailed geophysical investigation was undertaken along the route of the tunnel under the Thames. There was concern that a geological fault, (a fracture between two different blocks of rock) could have caused problems for the tunnel. The fault line was found slightly to the east of the tunnel’s proposed route.

The Thames Barrier sits astride the Greenwich Fault, and there are horizontal and vertical shifts of up to 50 meters and 5 metres respectively between the rock strata in the area around the barrier.

Seventy three boreholes were drilled during the planning of the Thames Barrier to check the ground beneath. There was concern that the chalk under the southern half of the site had been damaged during the ice age when frozen conditions could have resulted in the top layers of chalk crumbling into rubble, which would not have created a stable base for construction. Fascinating that we still have to consider the impact of the Ice Age on present day construction.

If you have exhausted the TV schedule, and Netflix, run out of alcohol, and the pubs are still not open, why not spend an evening browsing the British Geological Survey borehole portal. There are hundreds across the city. (The link brings up the UK map, click on the borehole scans at top left, geology transparency at top right to 100%, then zoom in to parts of London where the coloured dots of boreholes appear. Click on one of the dots to bring up information as to whether there is a scan available).

Boreholes for the Jubilee Line Extension, the new Thames Tideway Tunnel, historic boreholes drilled for water, such as the 600ft borehole beneath BBC’s Broadcasting House that was yielding 1,272 gallons of water an hour. Confidential or Restricted boreholes are spread across London. There are no online records for these, and it is intriguing to guess at the reason.

There was a potential attempt at drilling again at the original Willesden site, when London Local Energy applied for a licence to drill and search for oil and gas in 2014. The company believed that whilst small quantities had been found in the earlier boreholes, new fracking technology would allow an economic quantity to be recovered. The application did not make any progress.

Despite the considerable number of boreholes, no commercial oil has ever been found in London, so Willesden, or anywhere else in London will never see an oil bonanza.