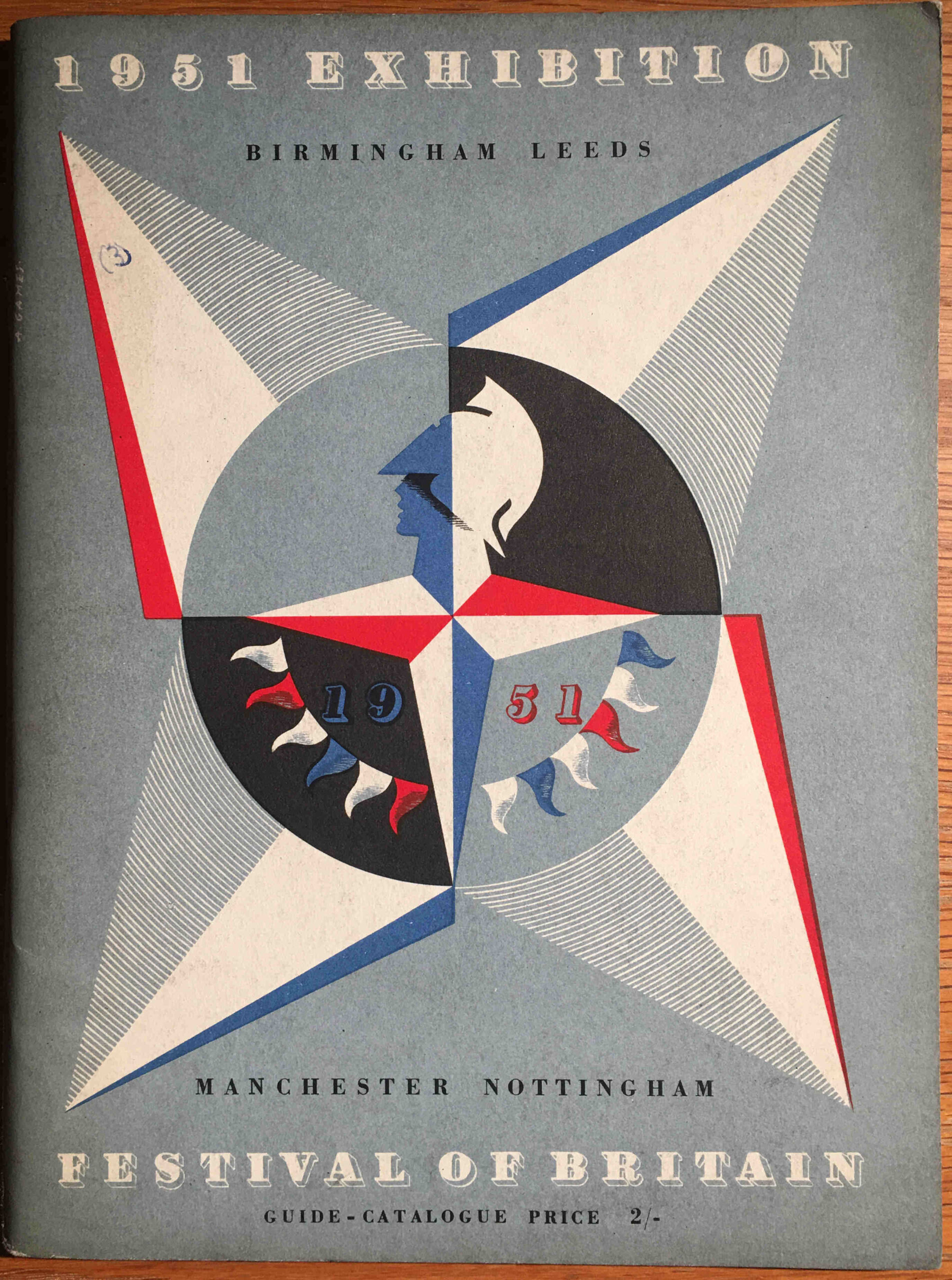

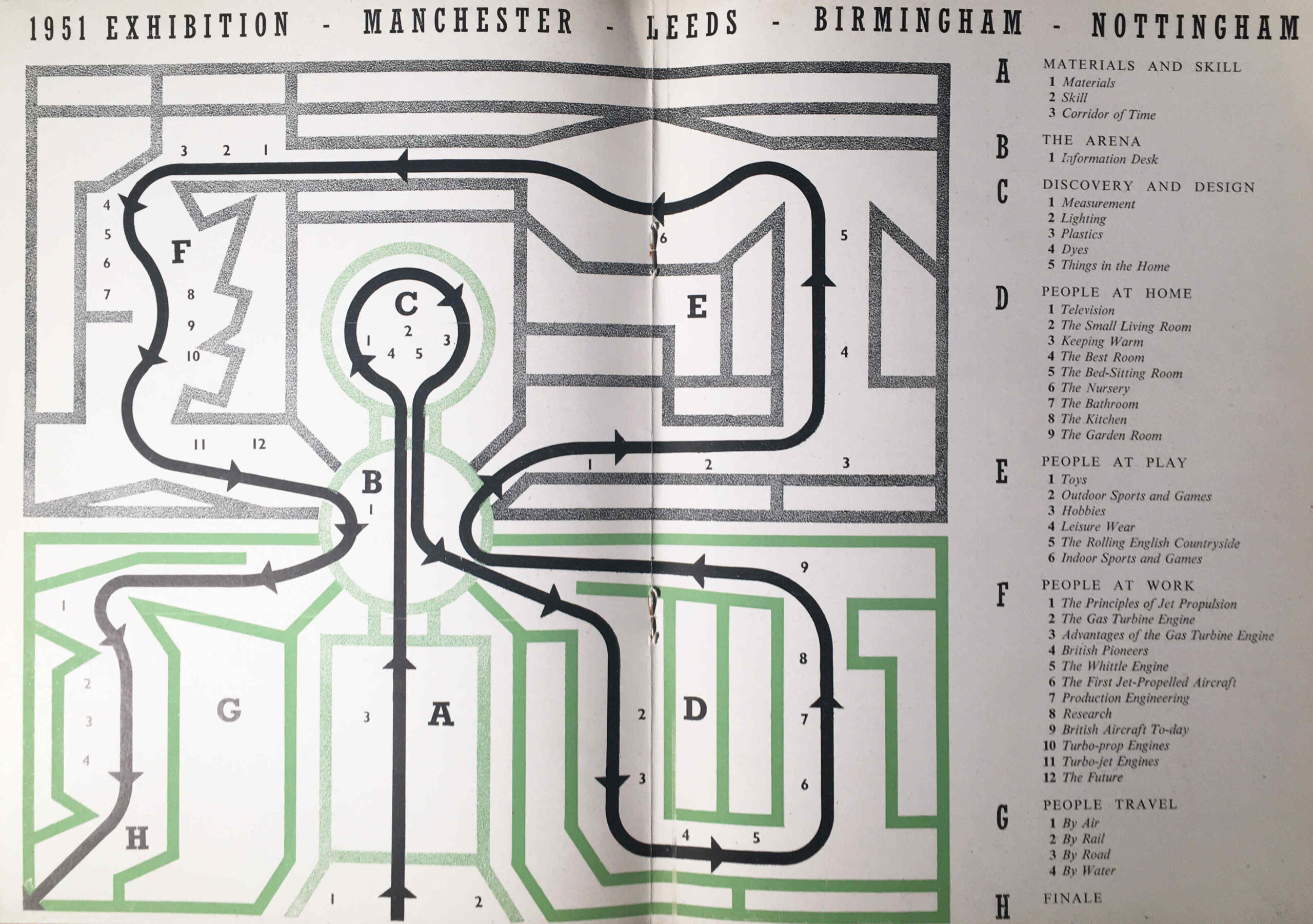

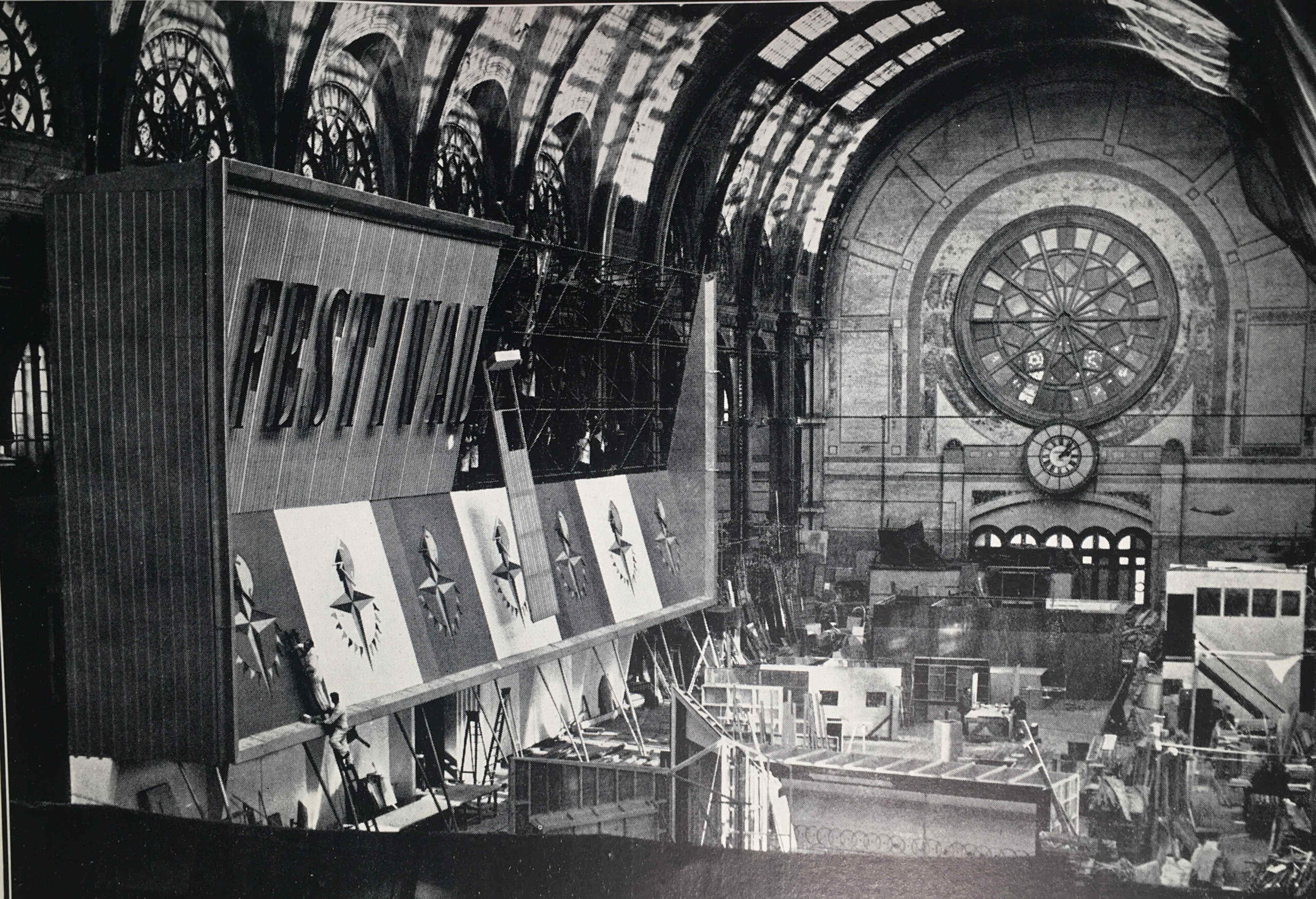

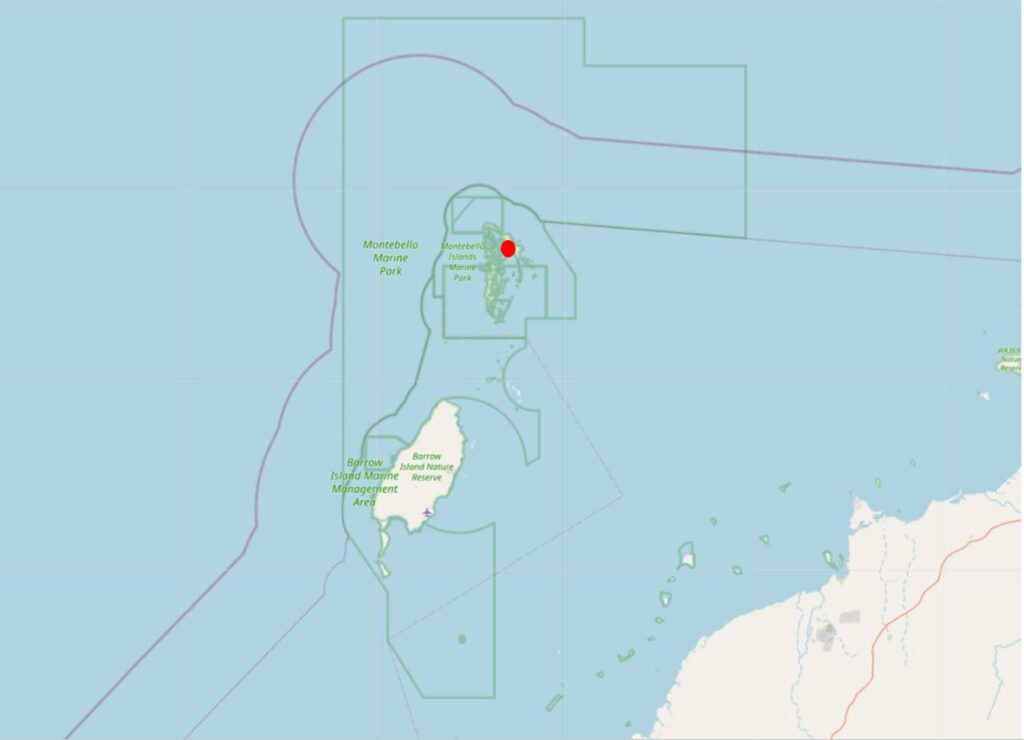

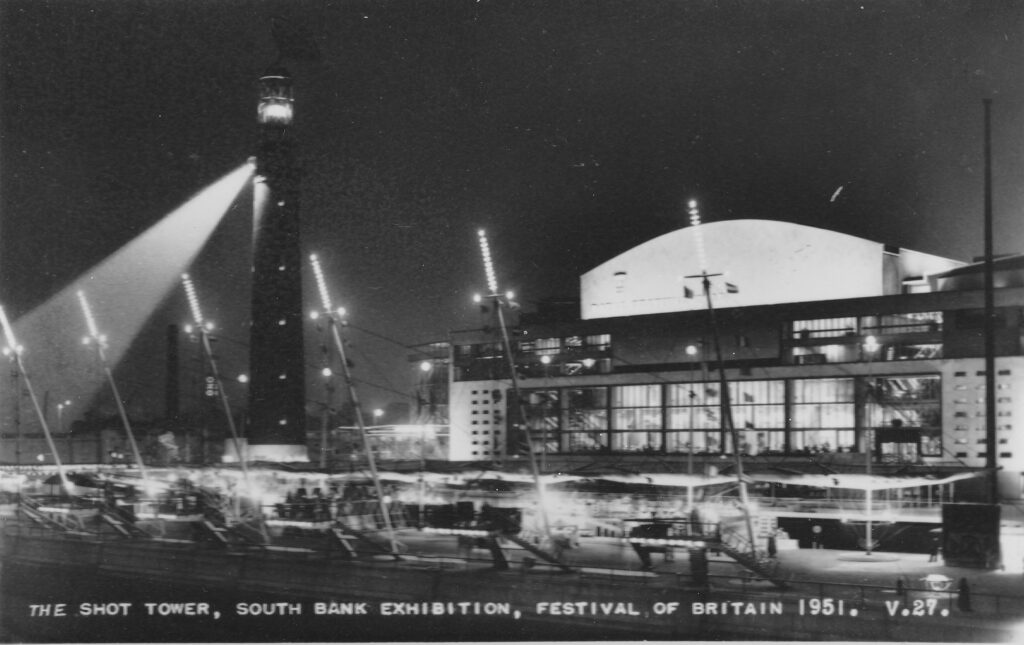

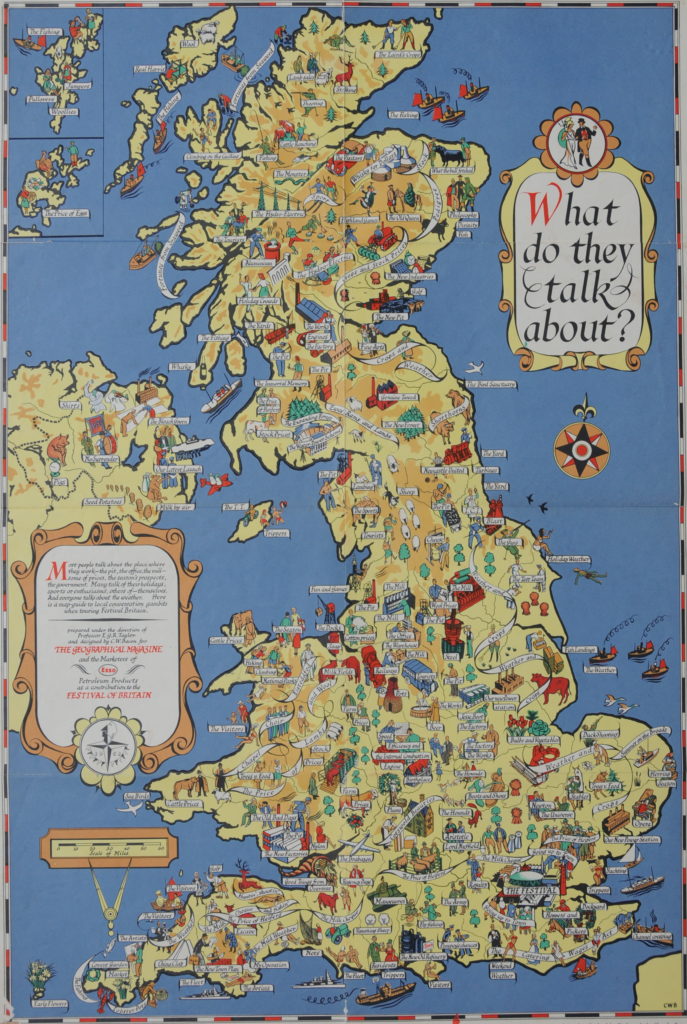

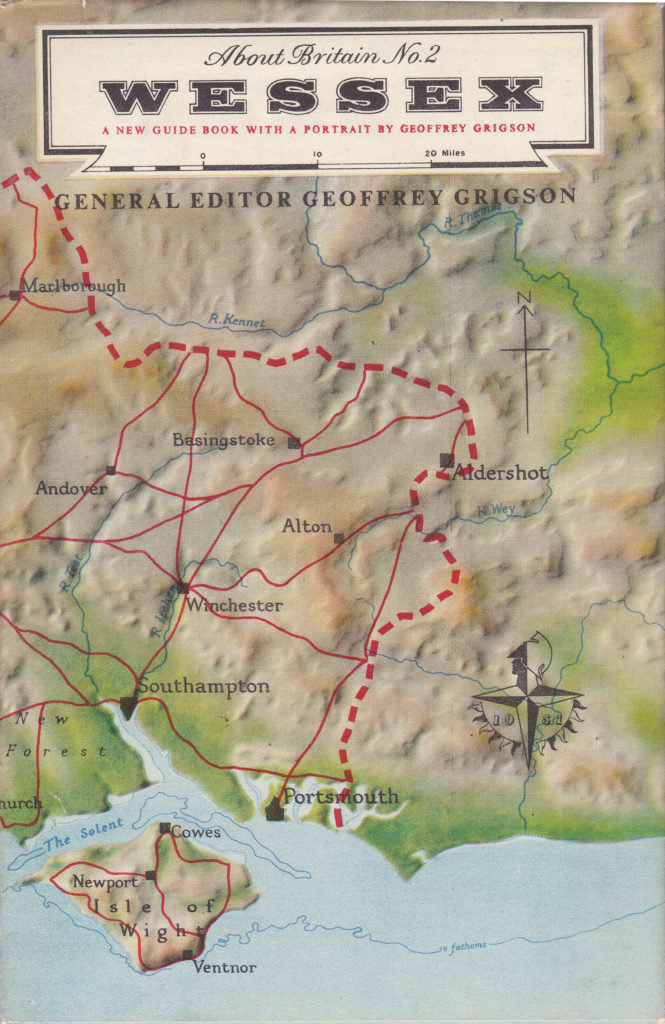

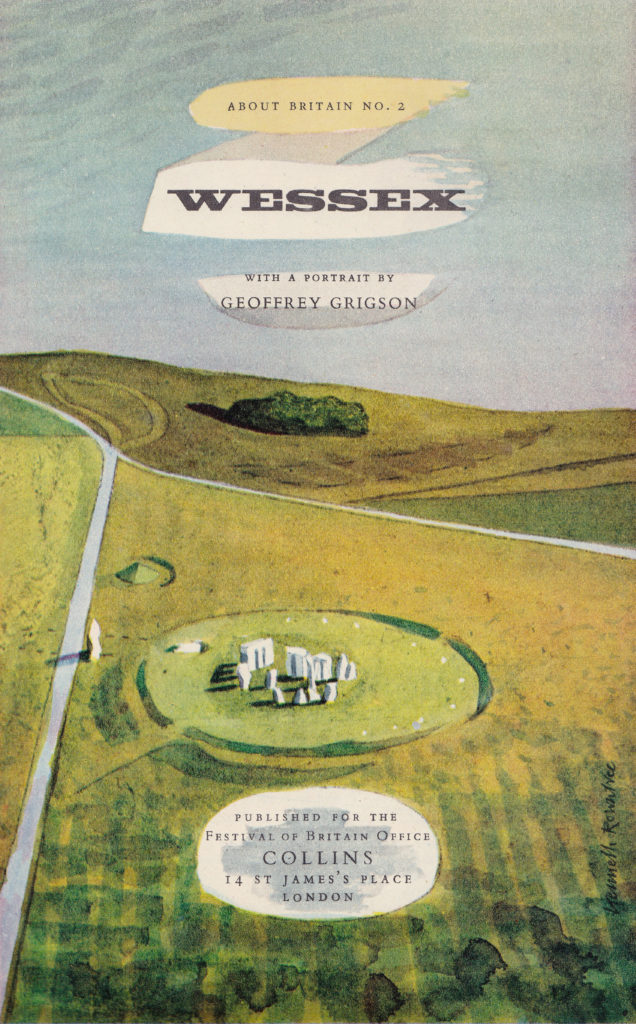

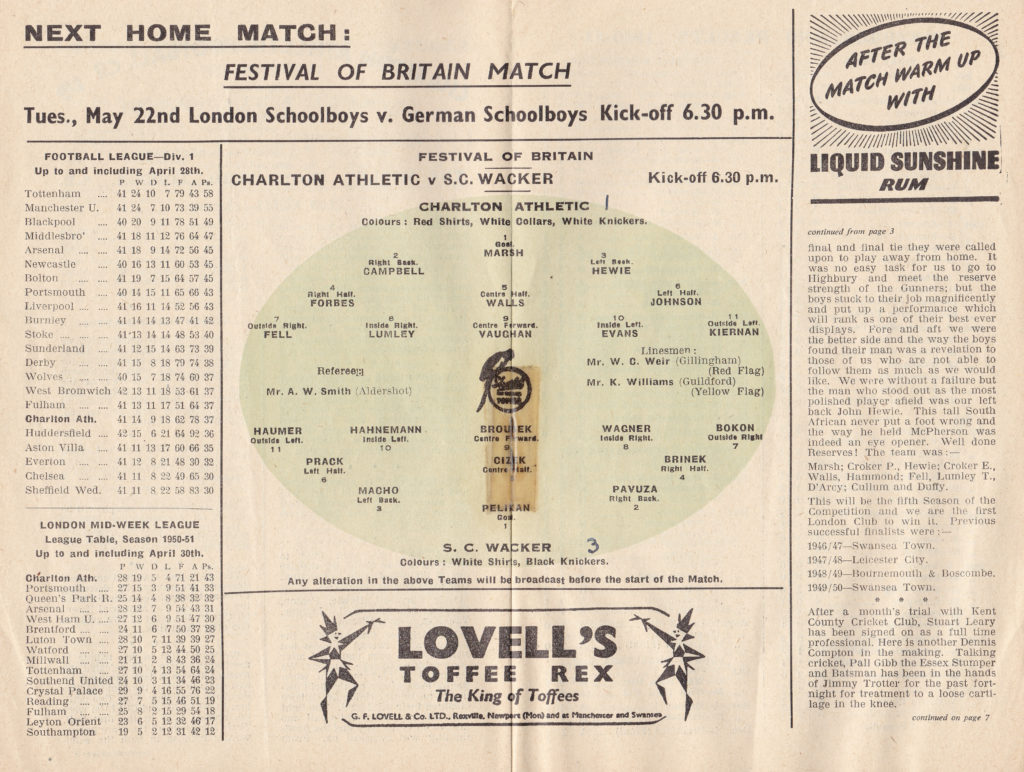

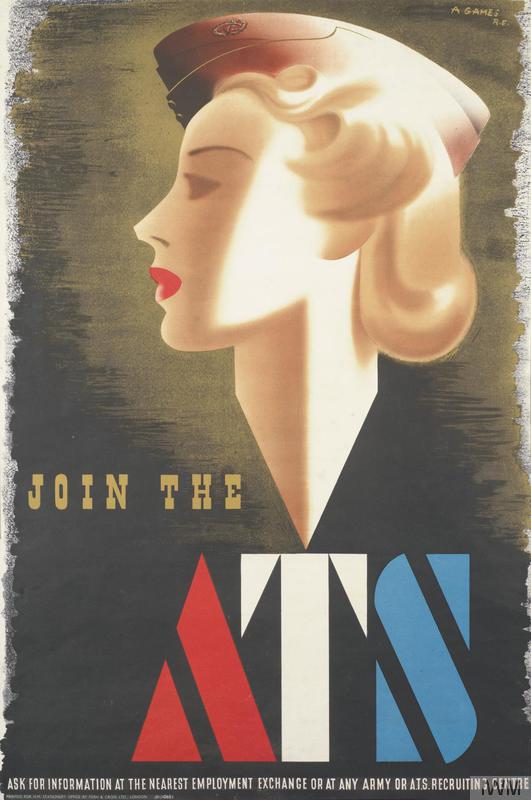

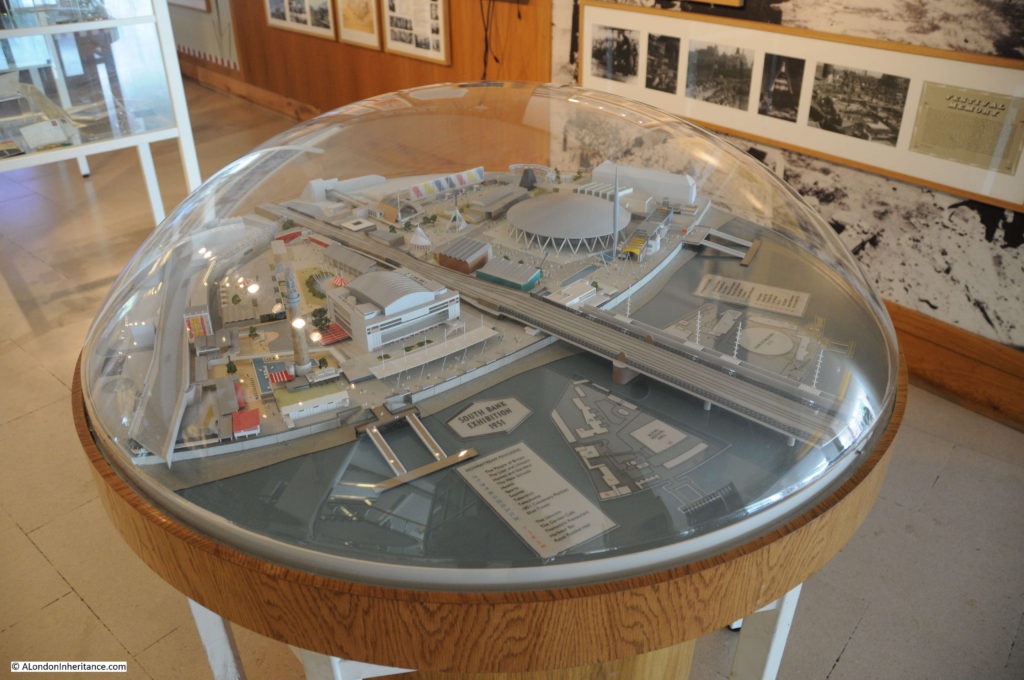

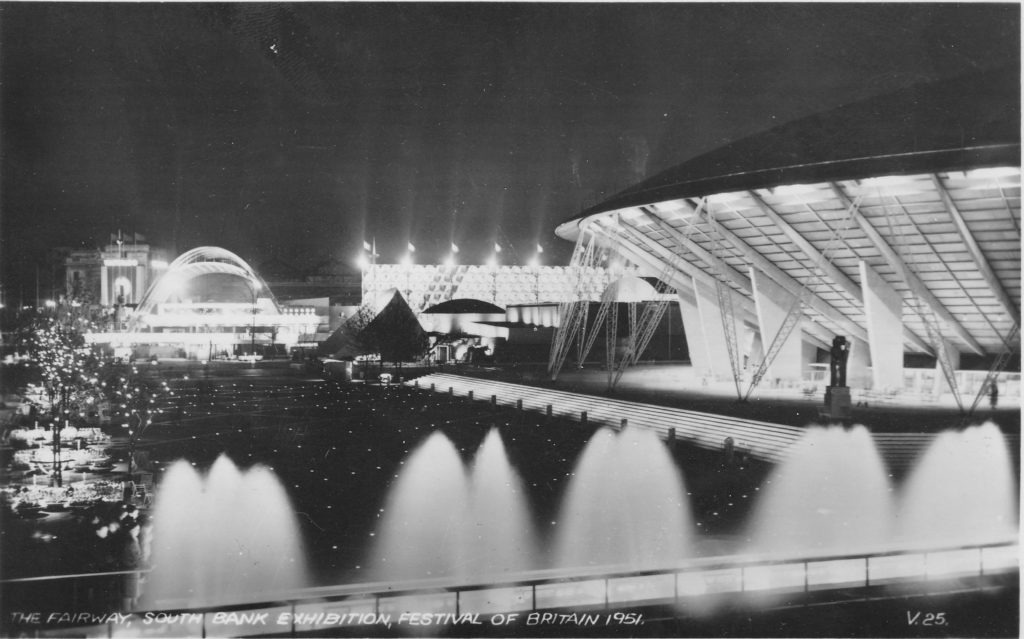

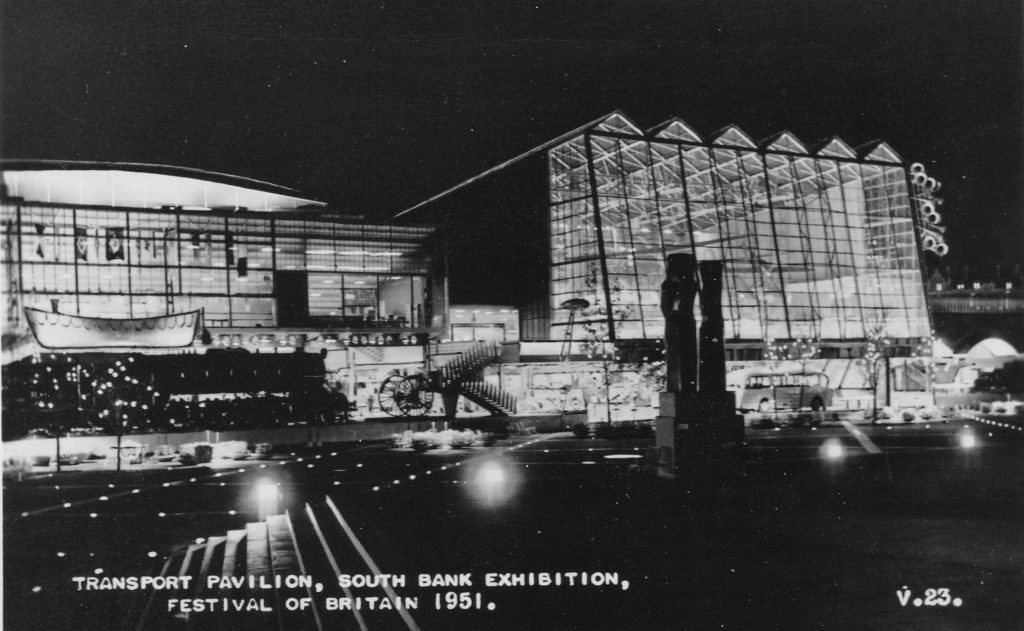

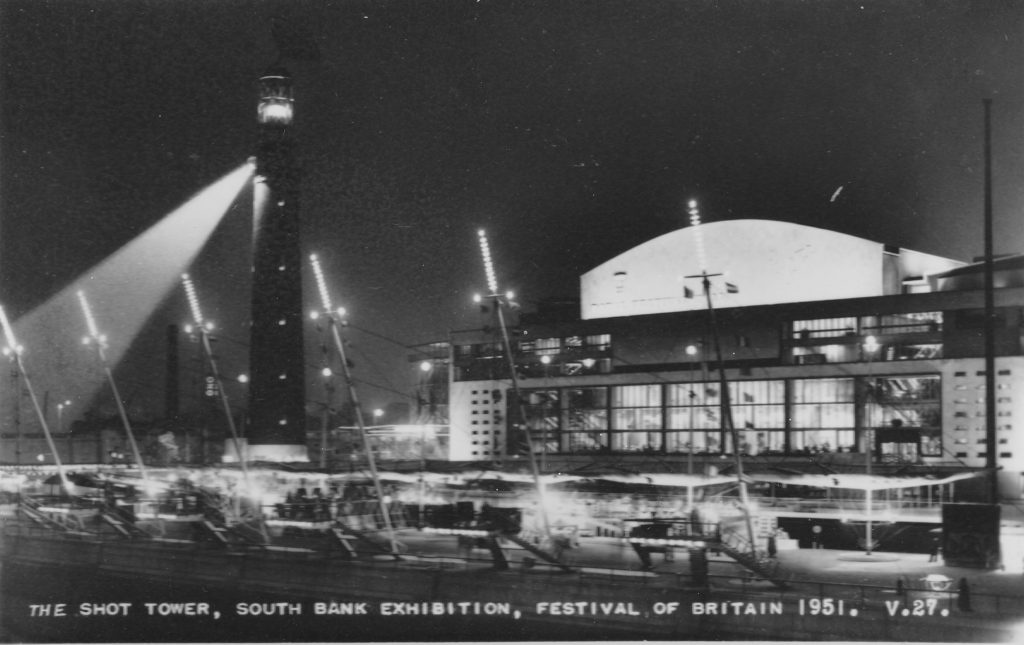

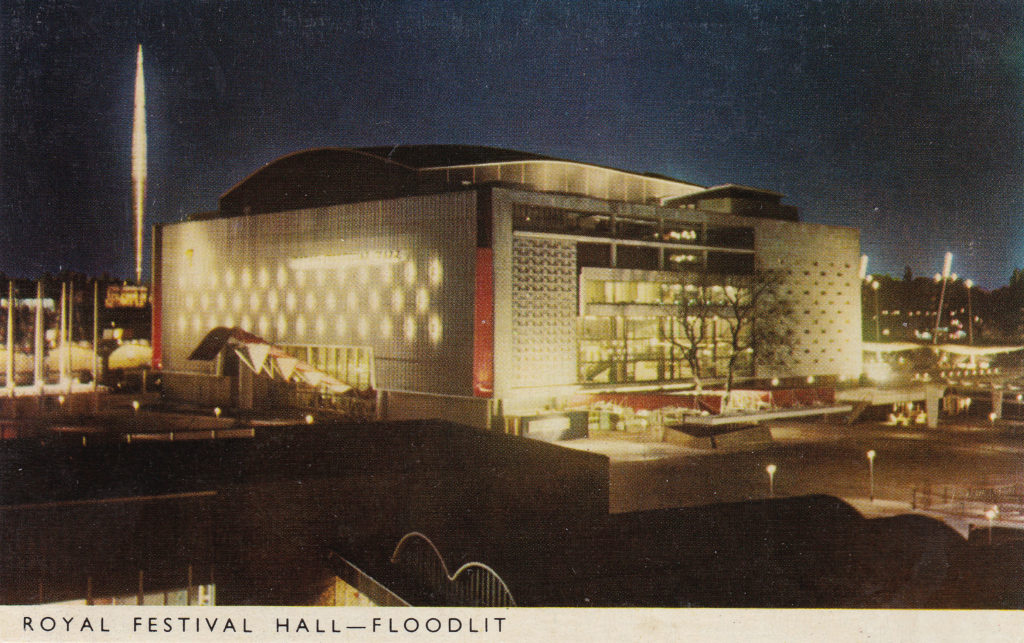

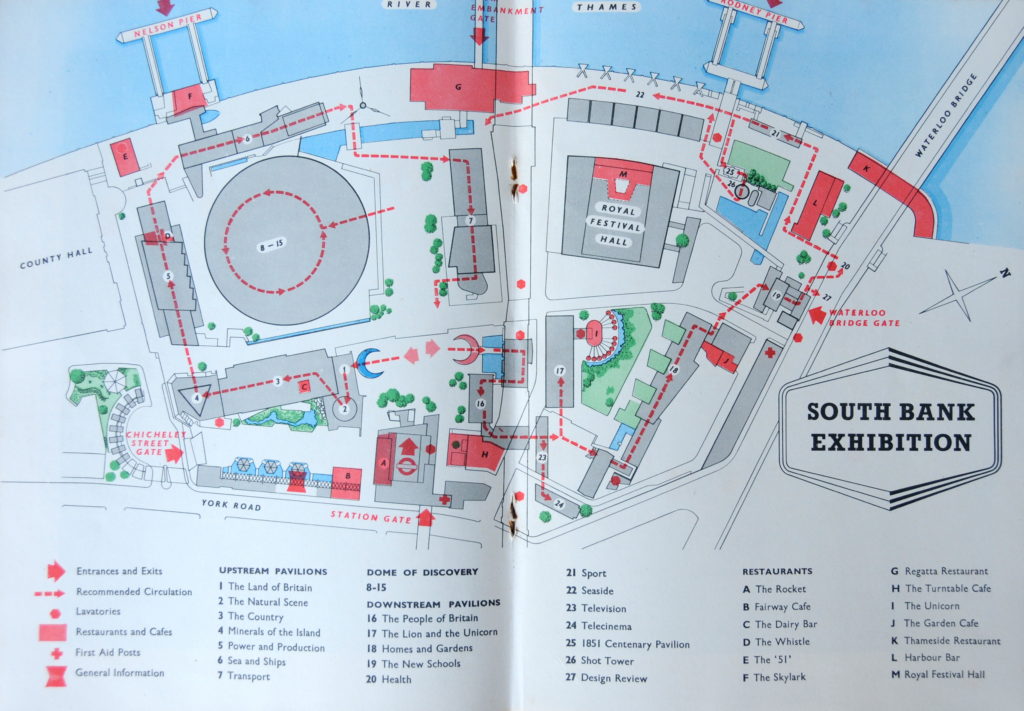

A mix of subjects for this week’s post, the first comes from my fascination with all things Festival of Britain, and where we can see aspects of the festival to this day.

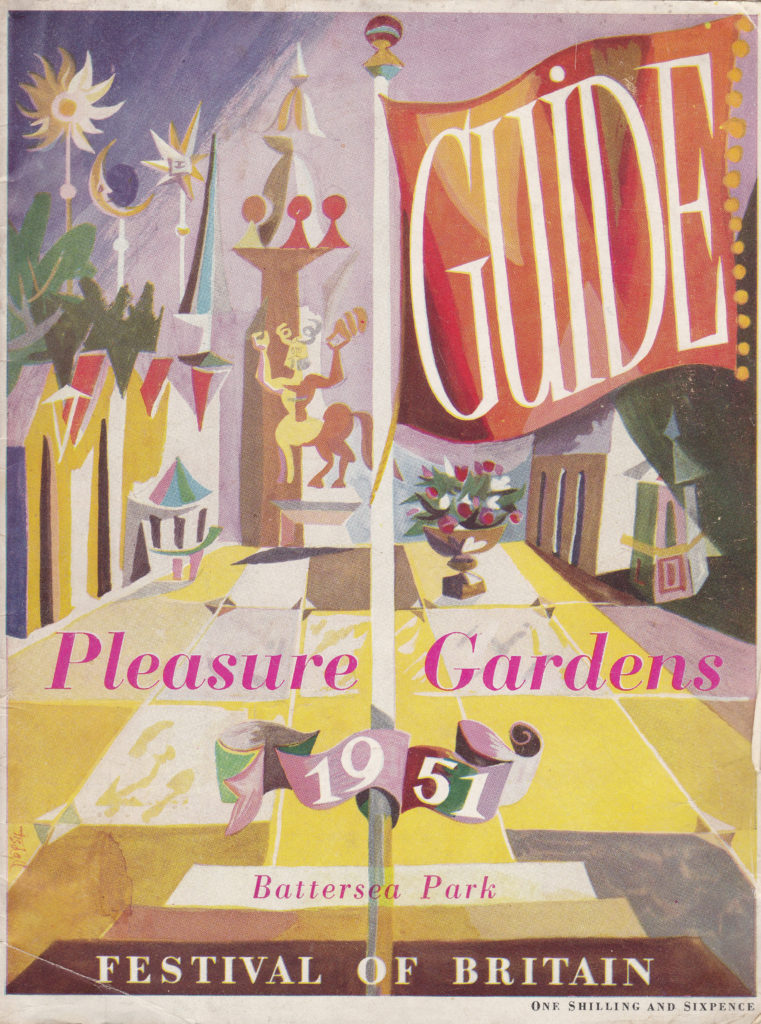

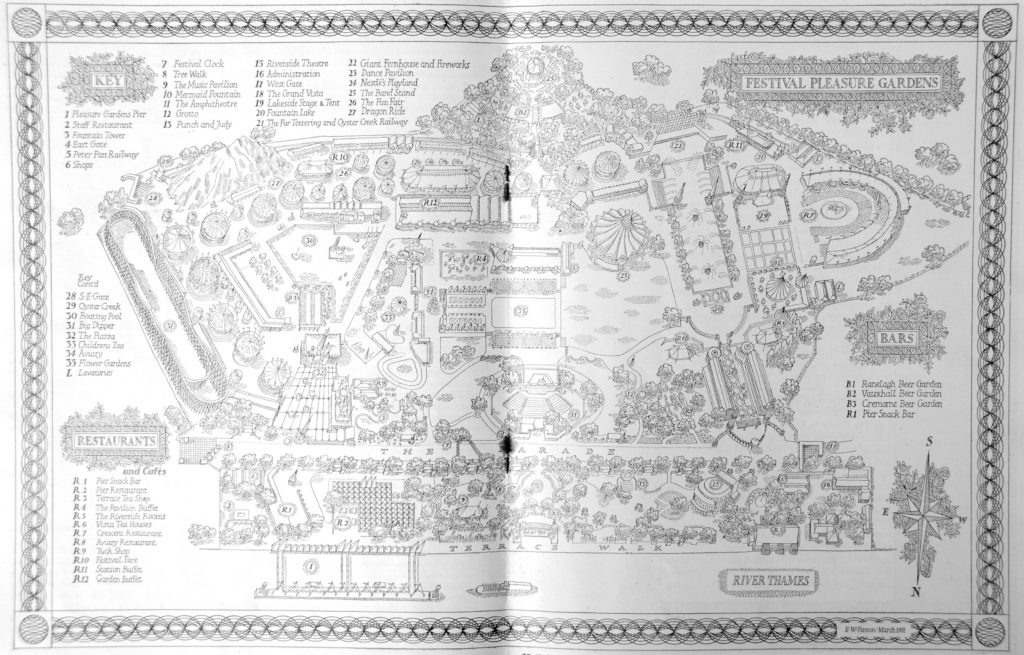

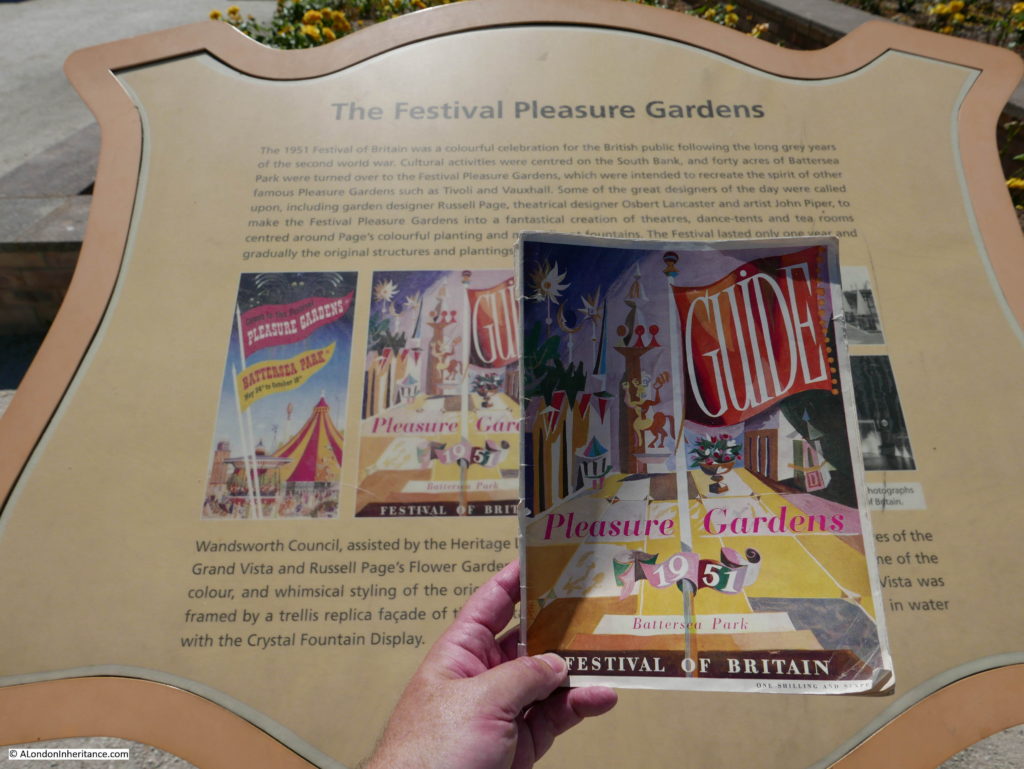

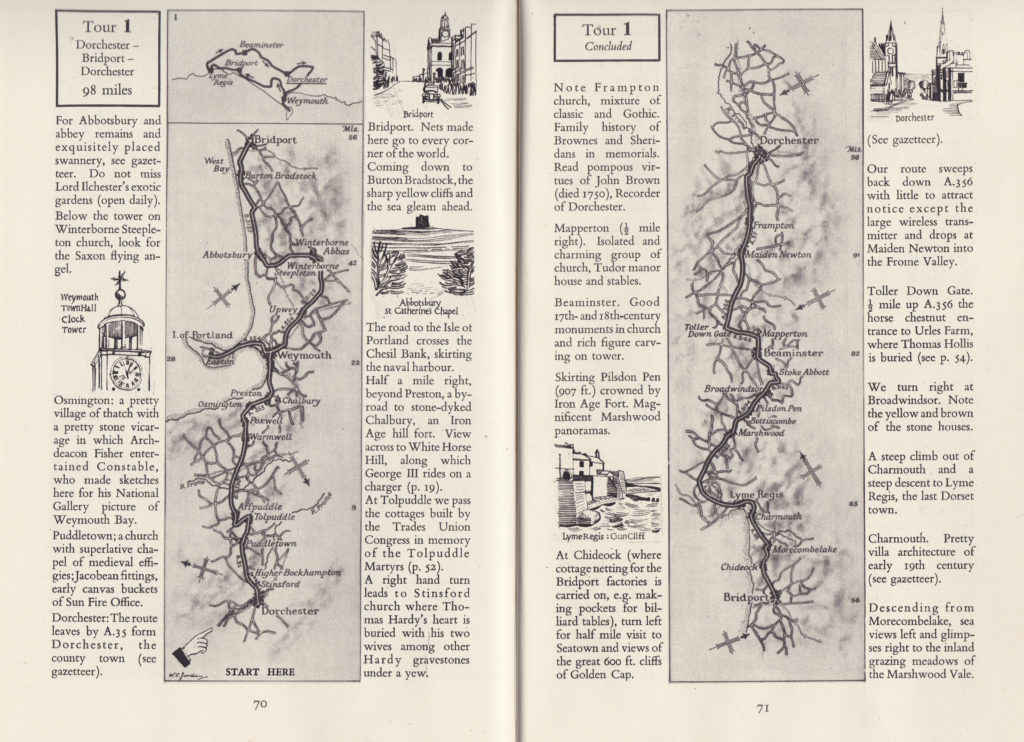

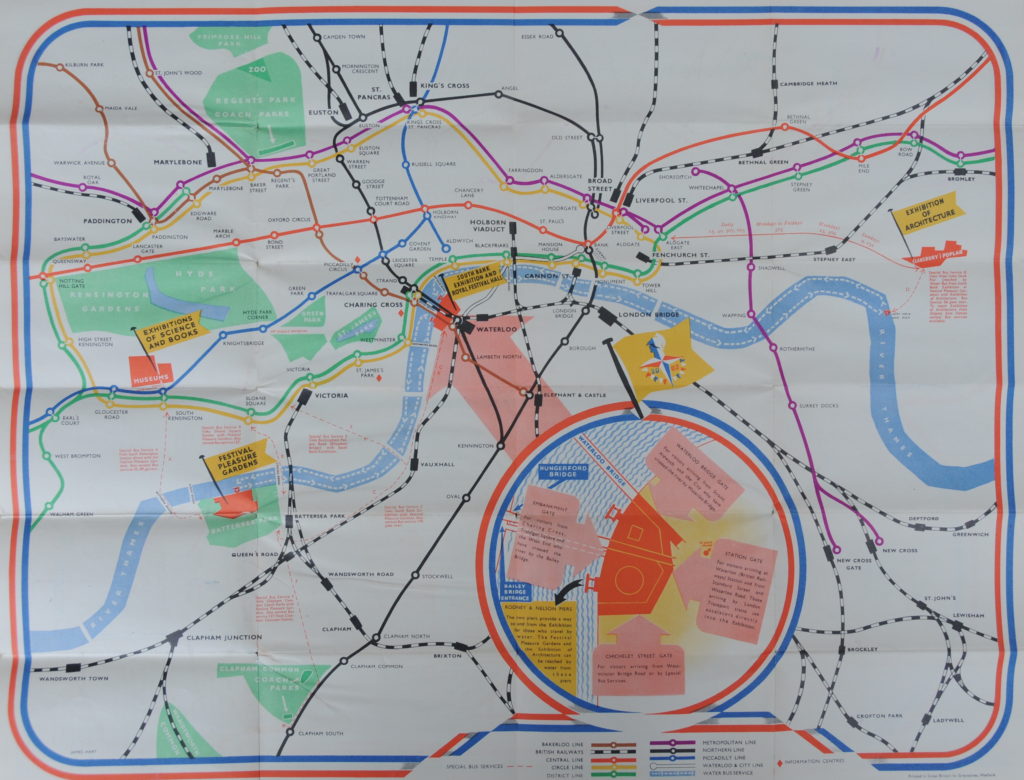

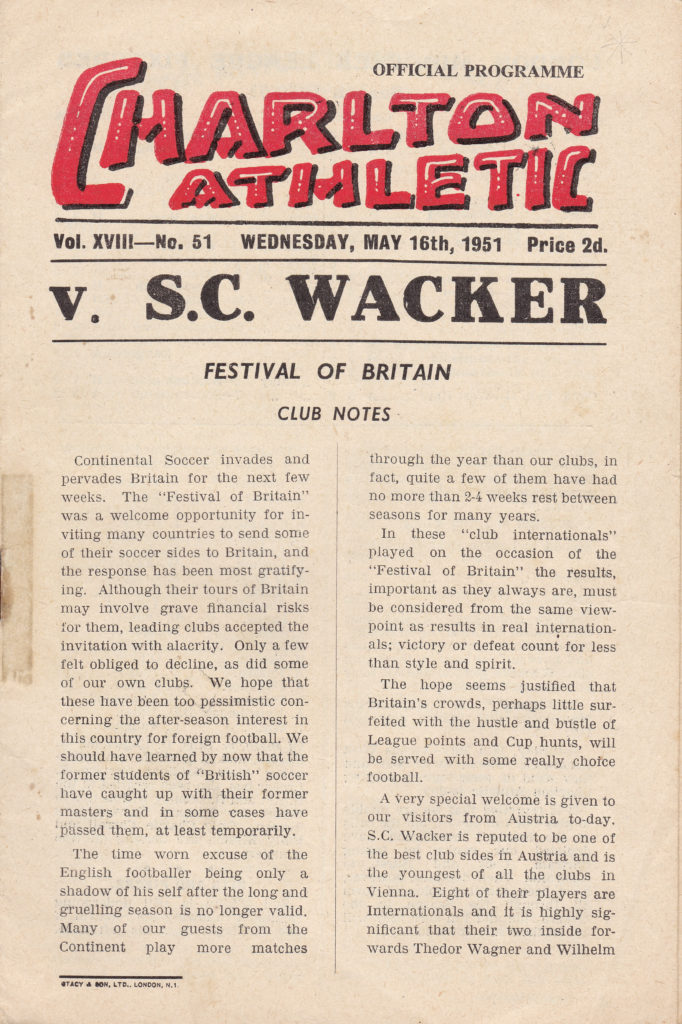

Part of the Festival of Britain in 1951 was the Festival Pleasure Gardens at Battersea. I wrote a post about the pleasure gardens which can be found by clicking here.

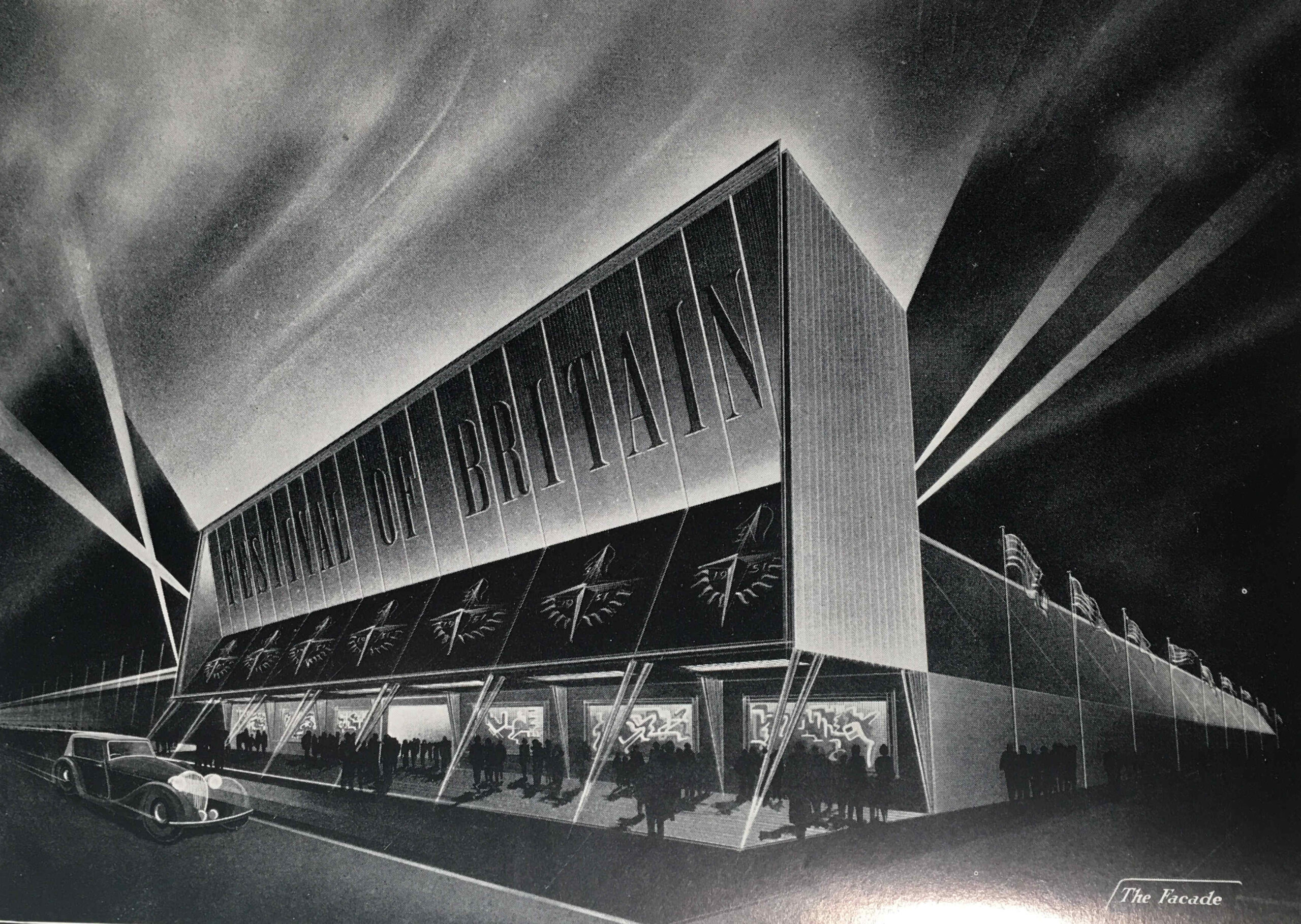

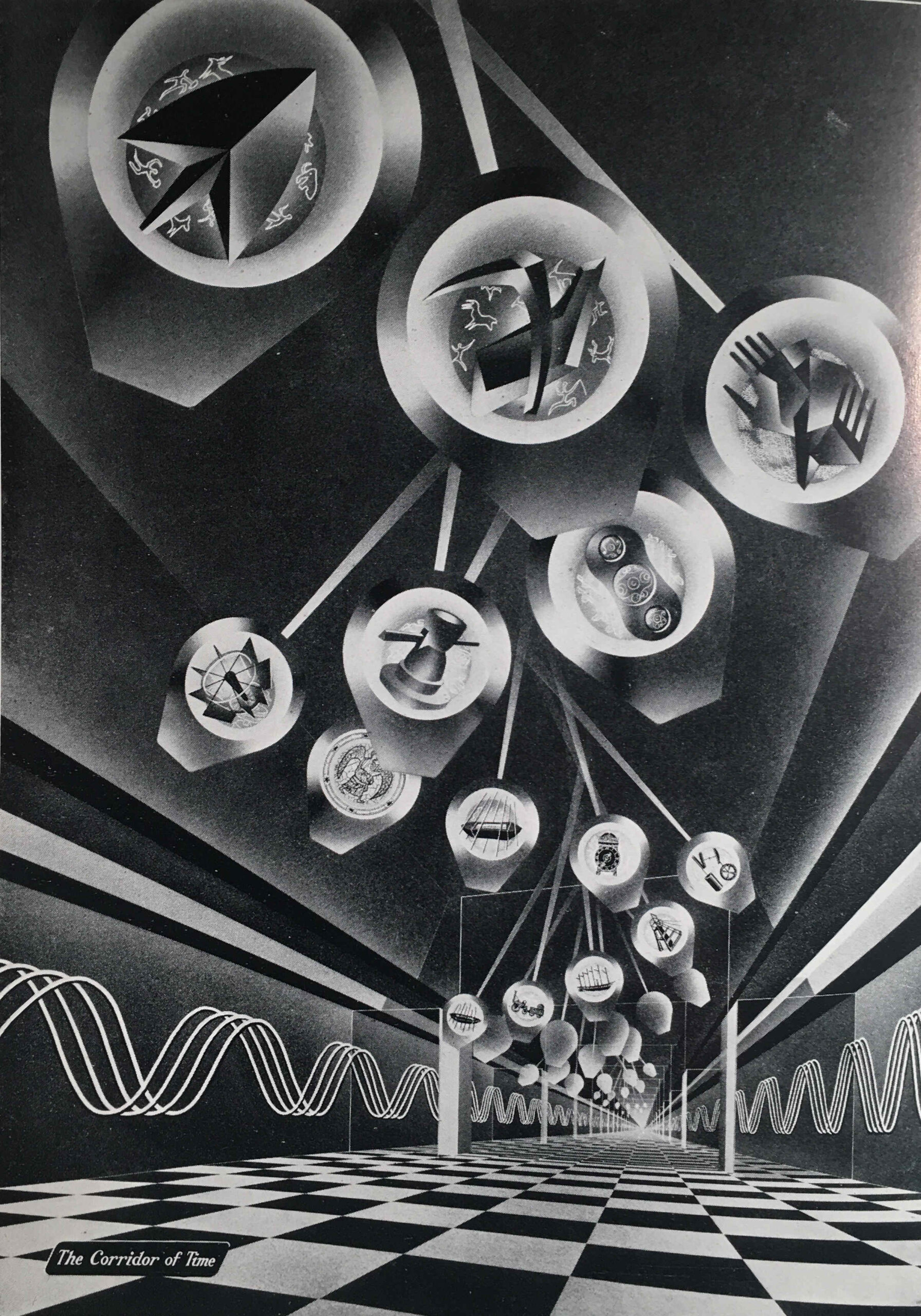

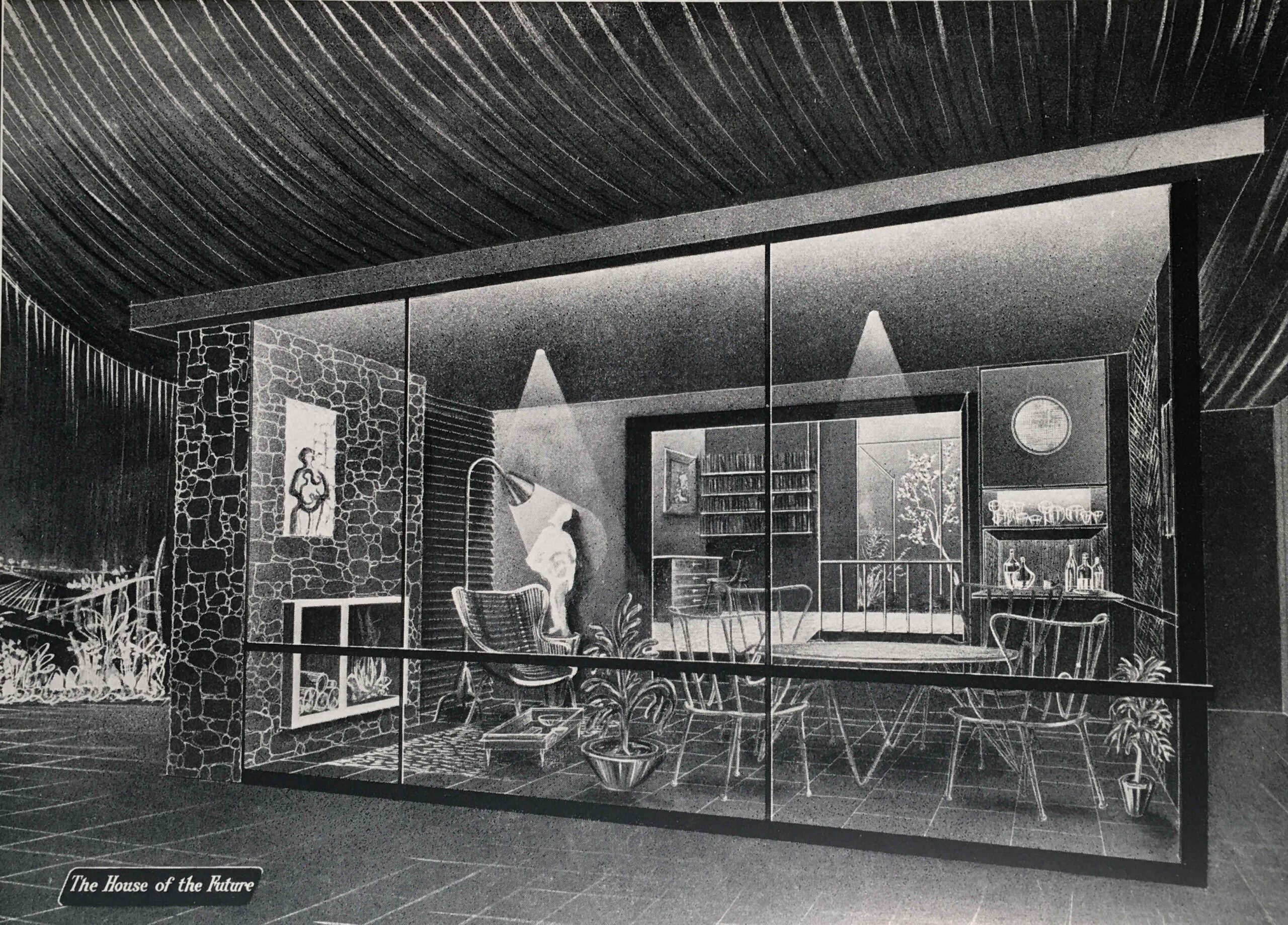

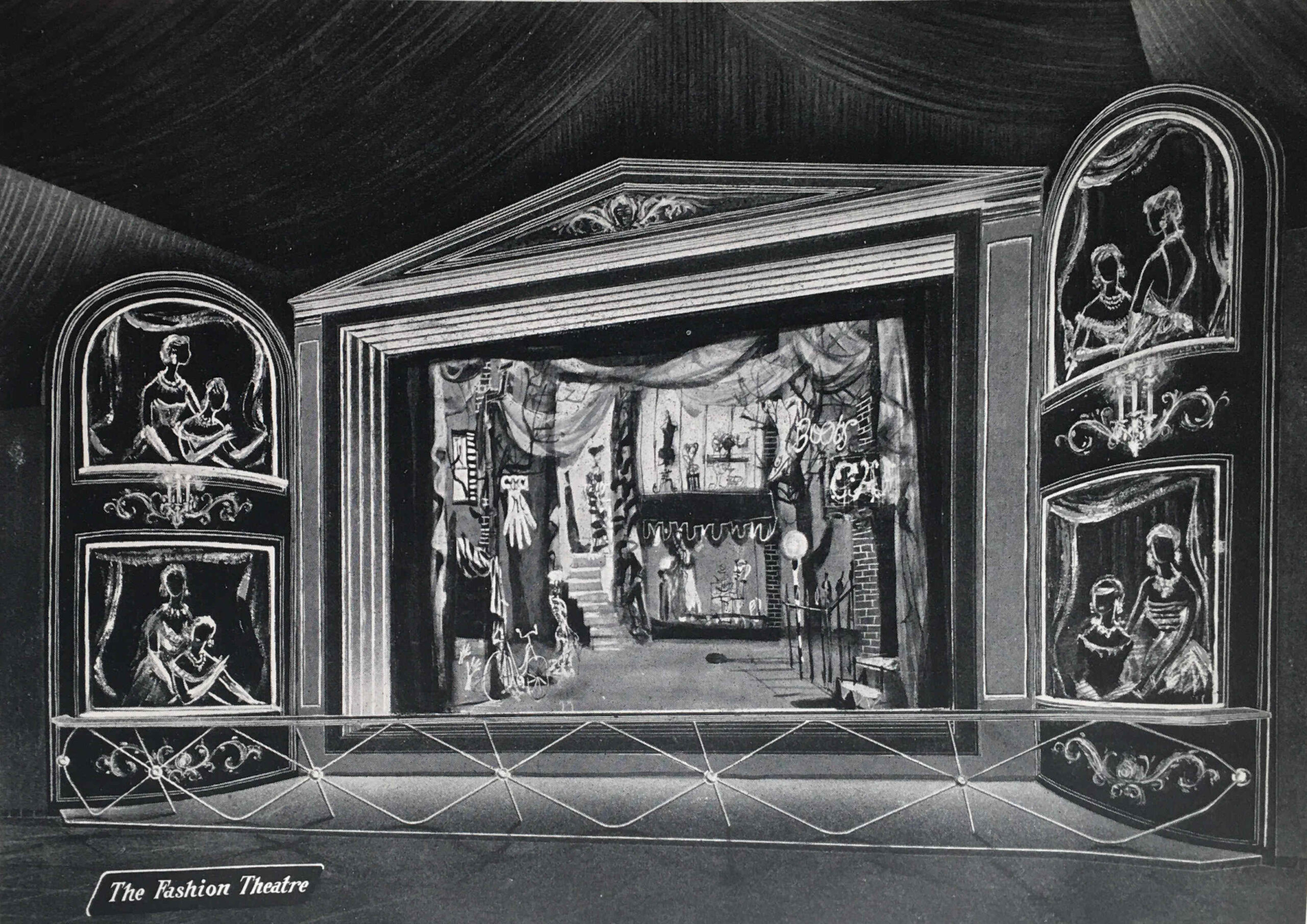

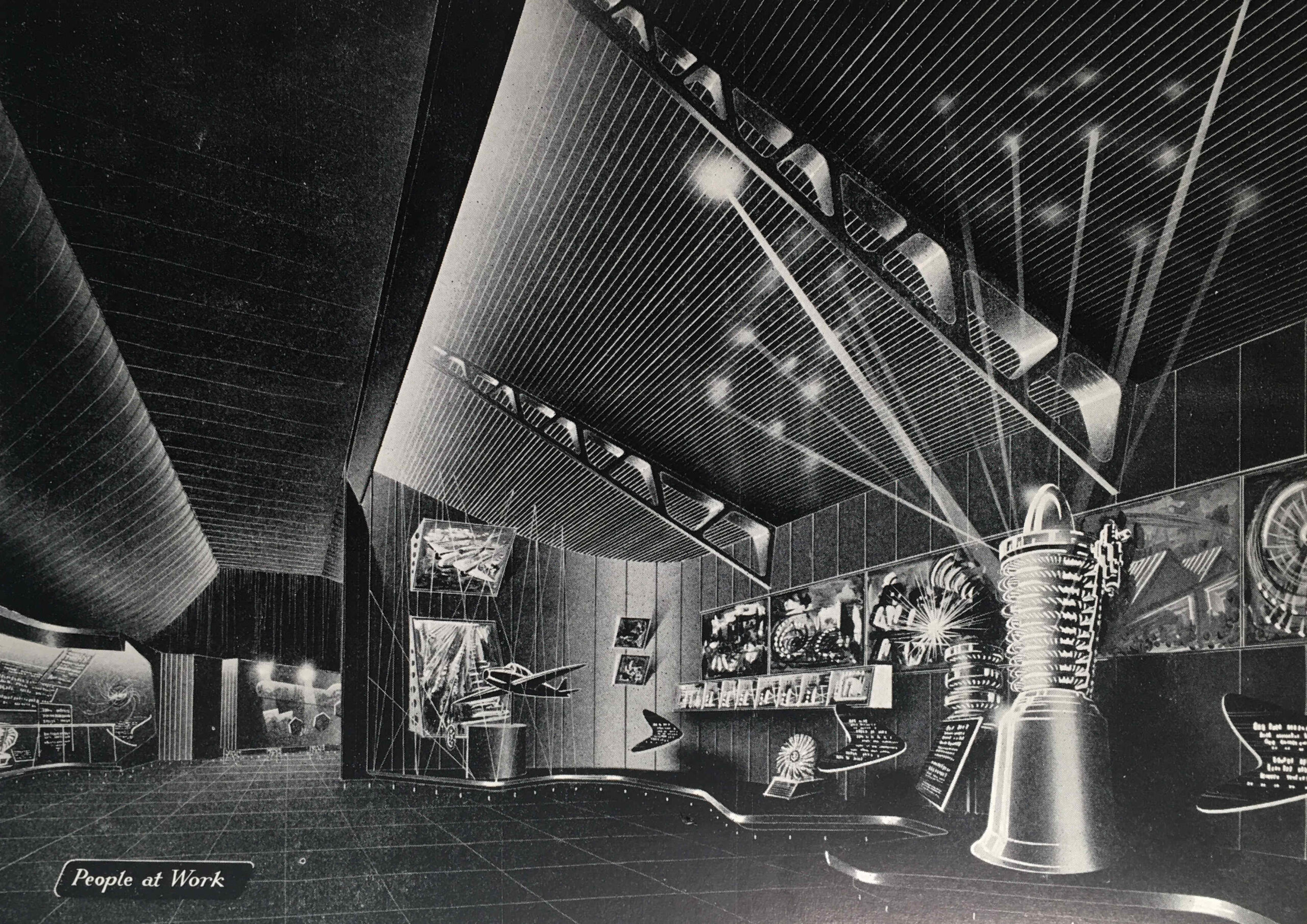

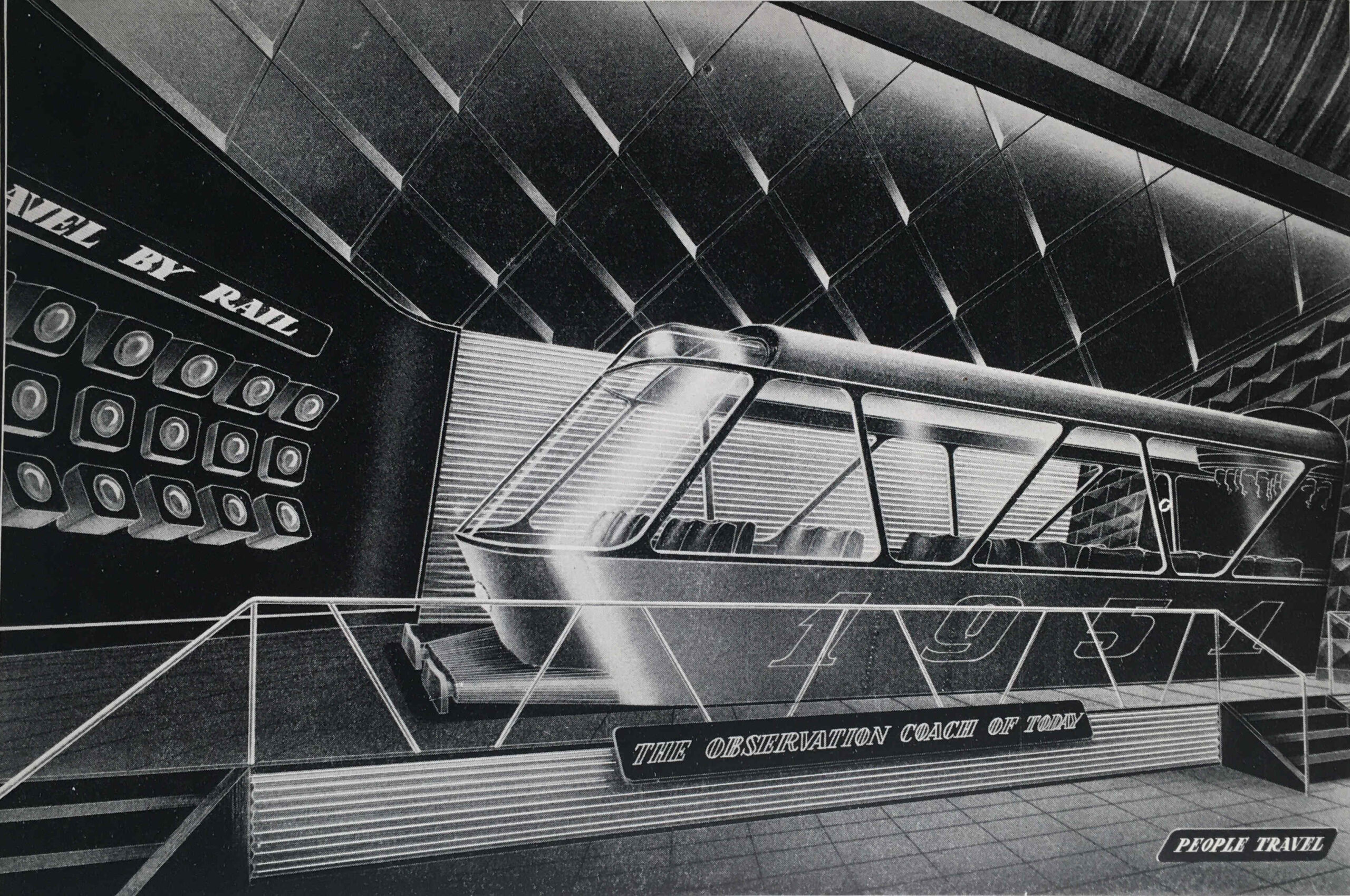

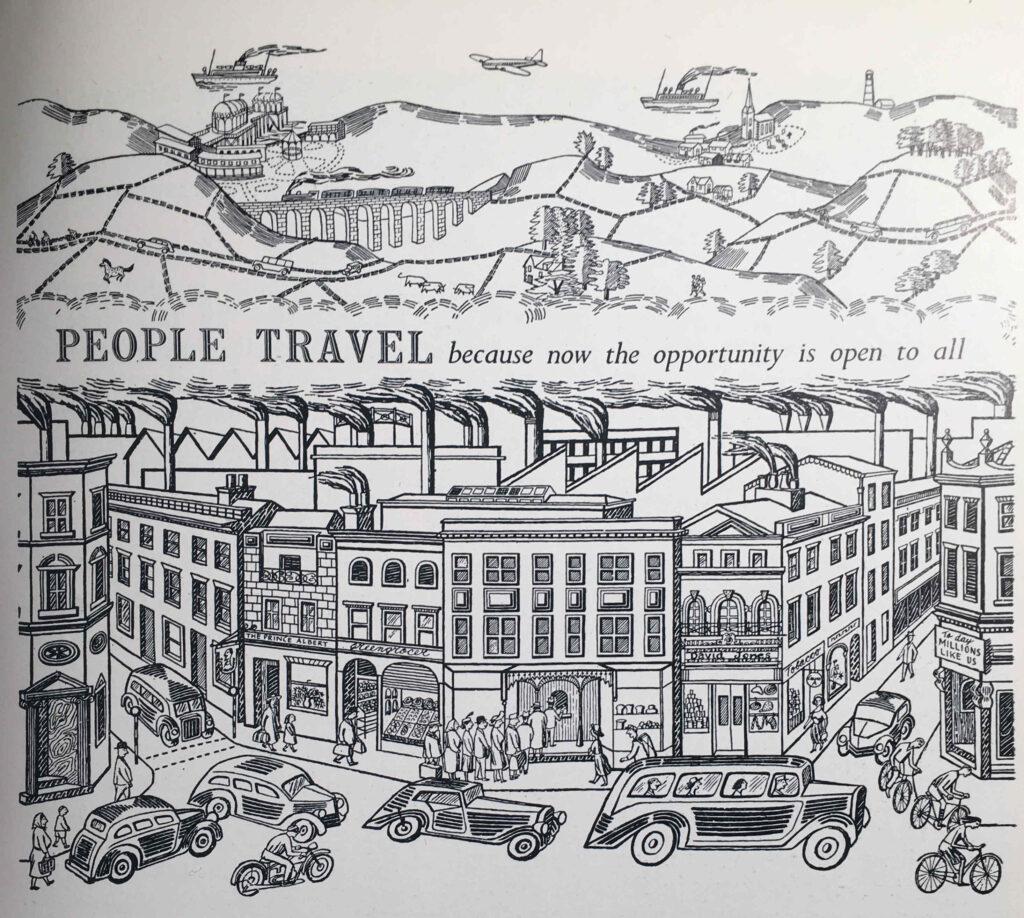

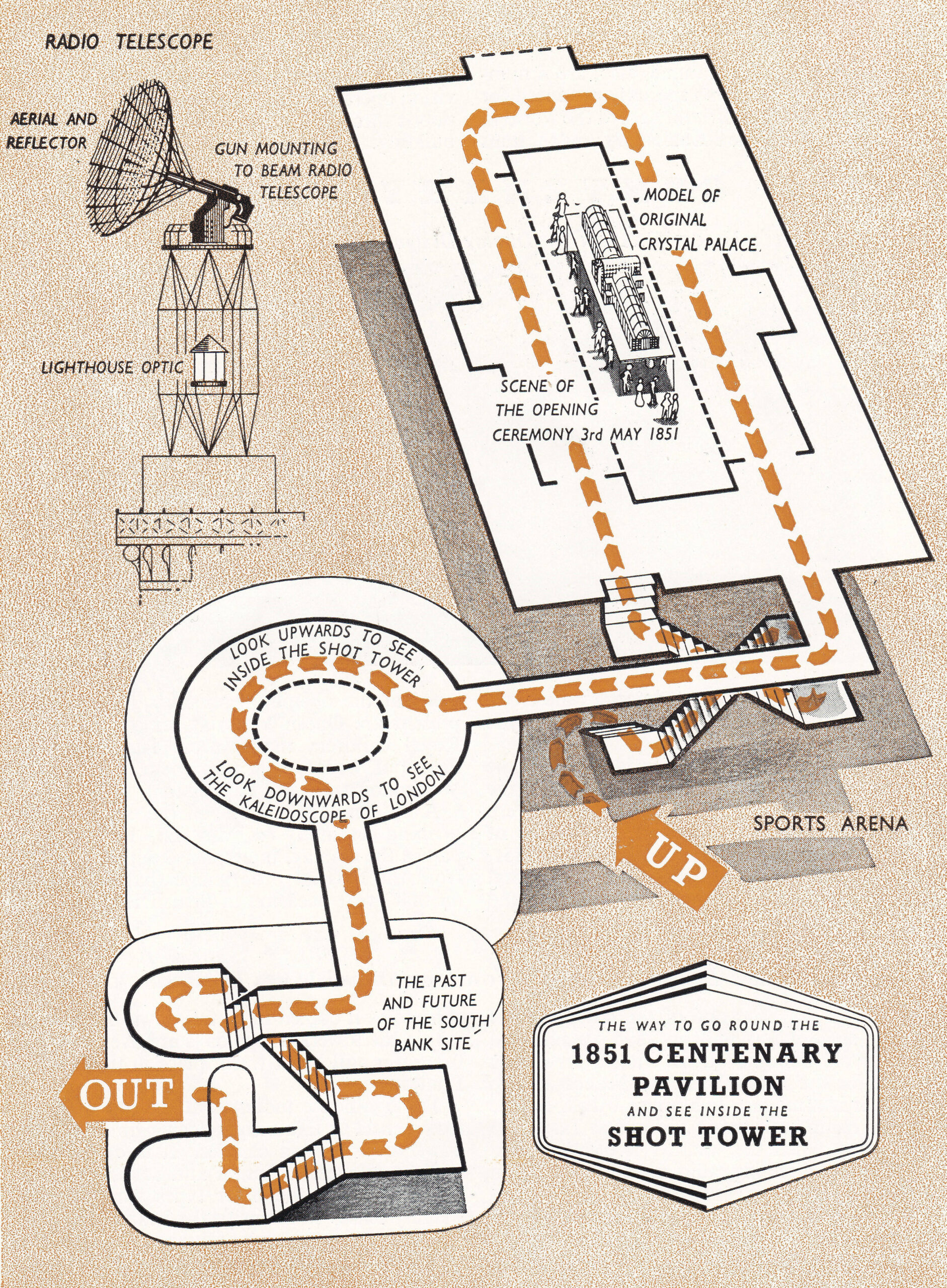

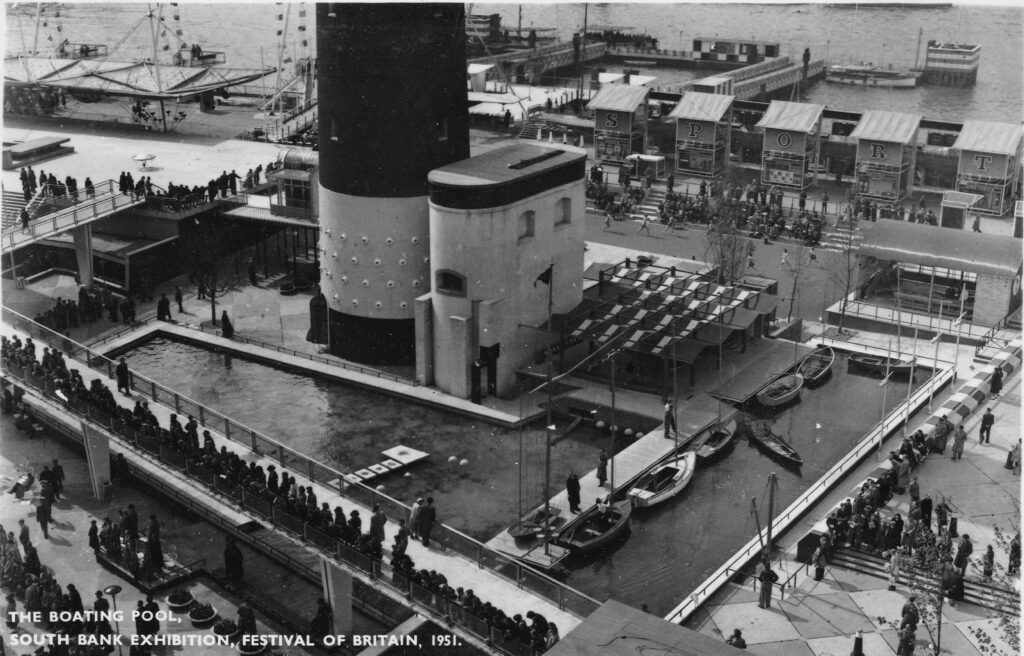

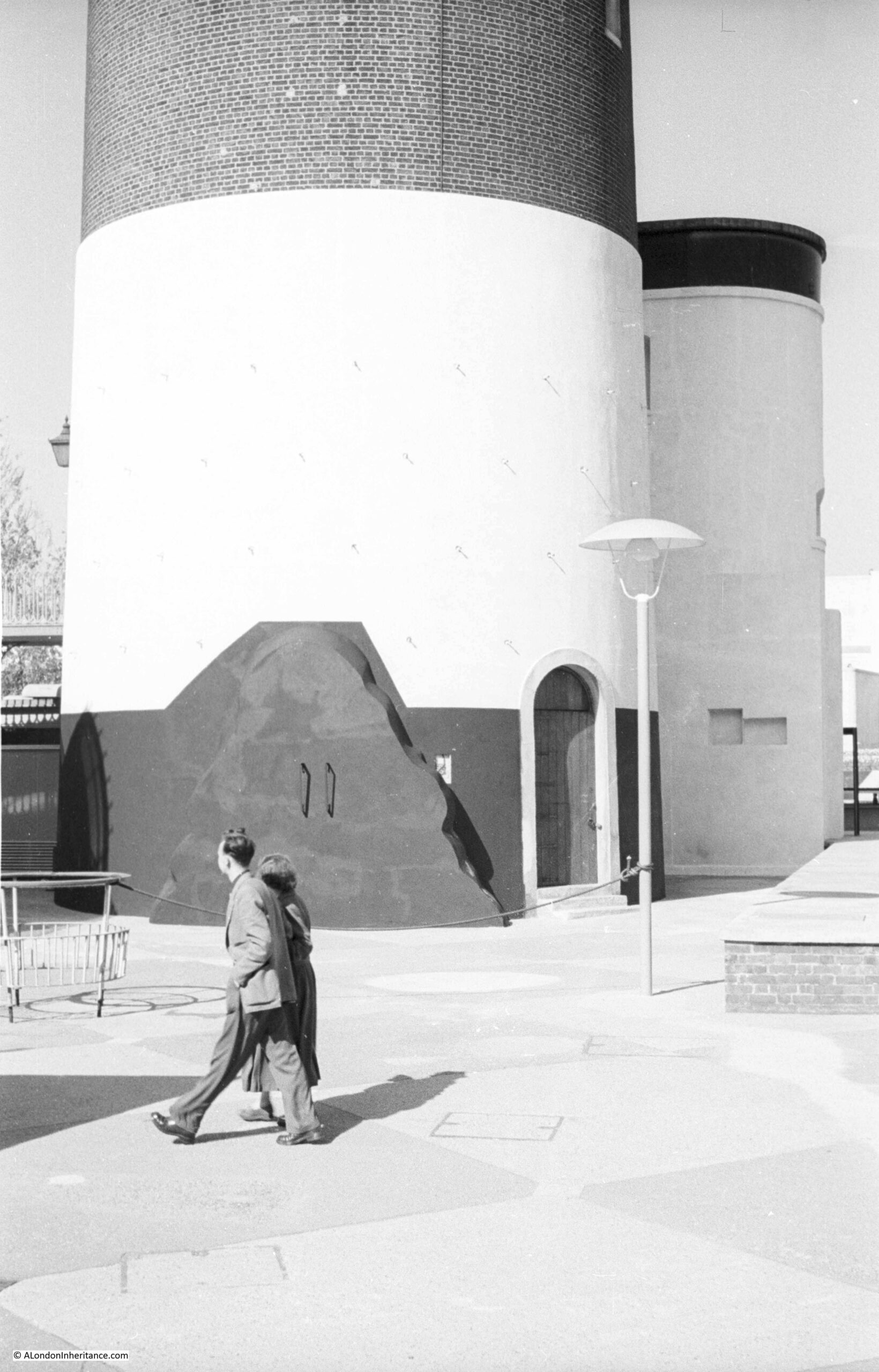

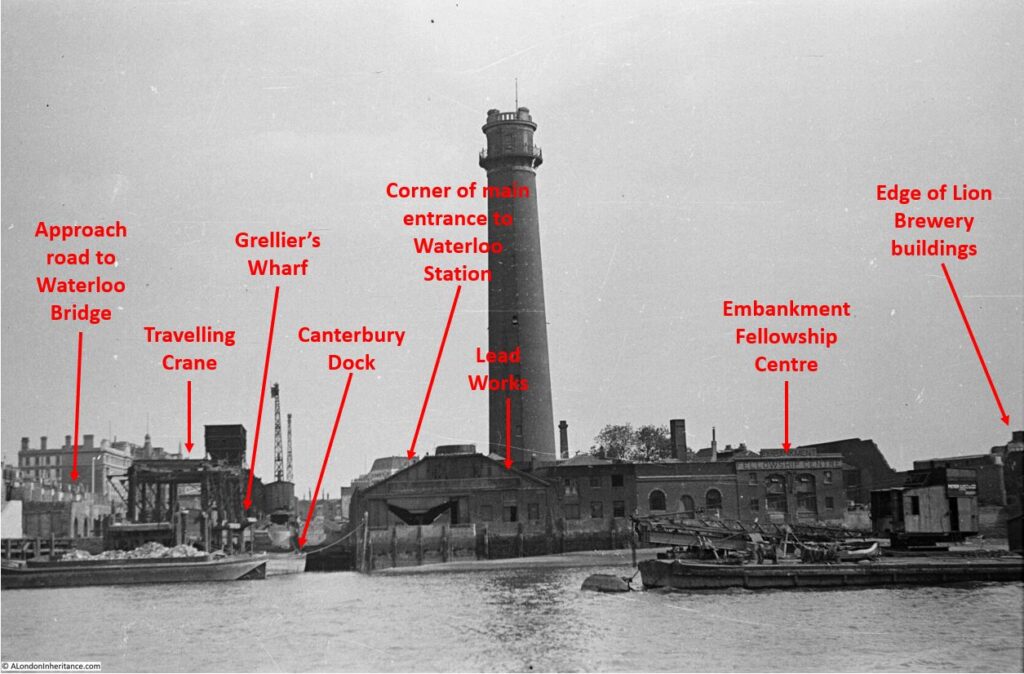

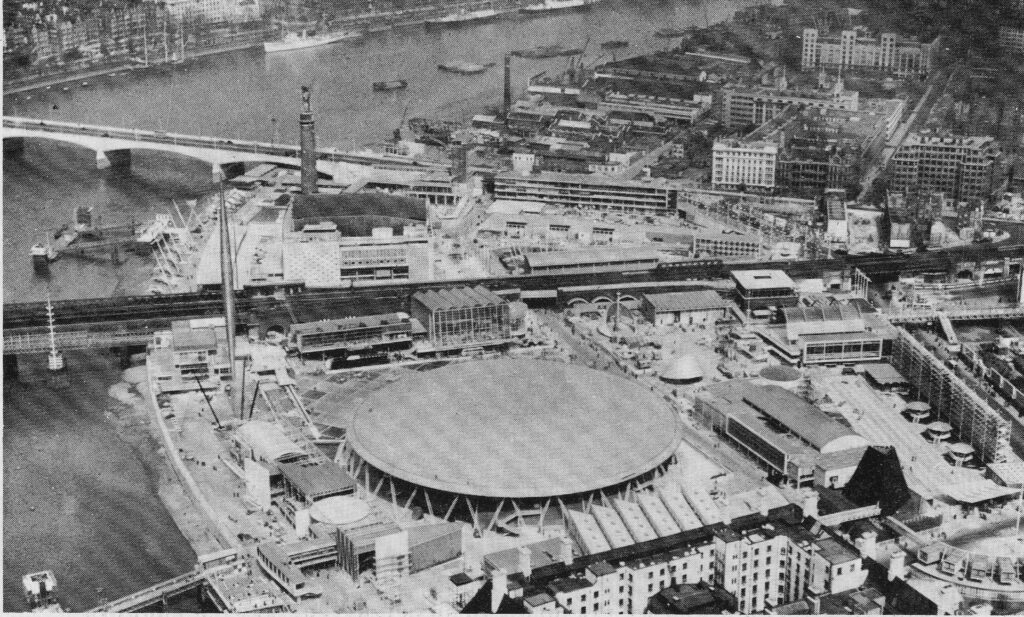

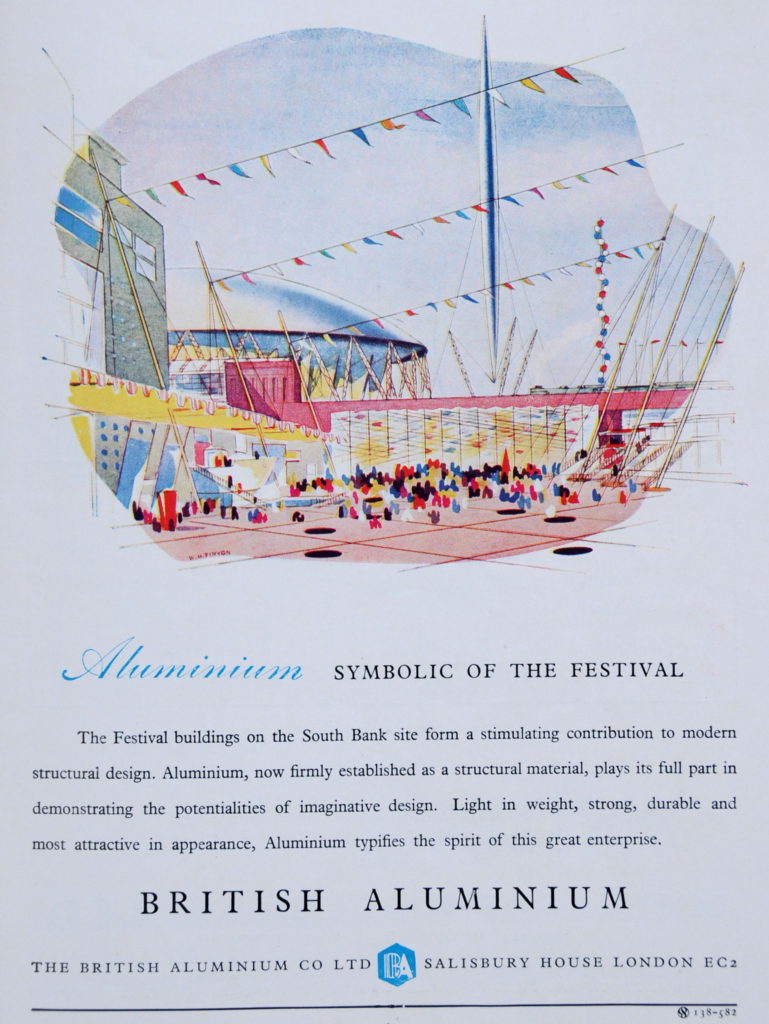

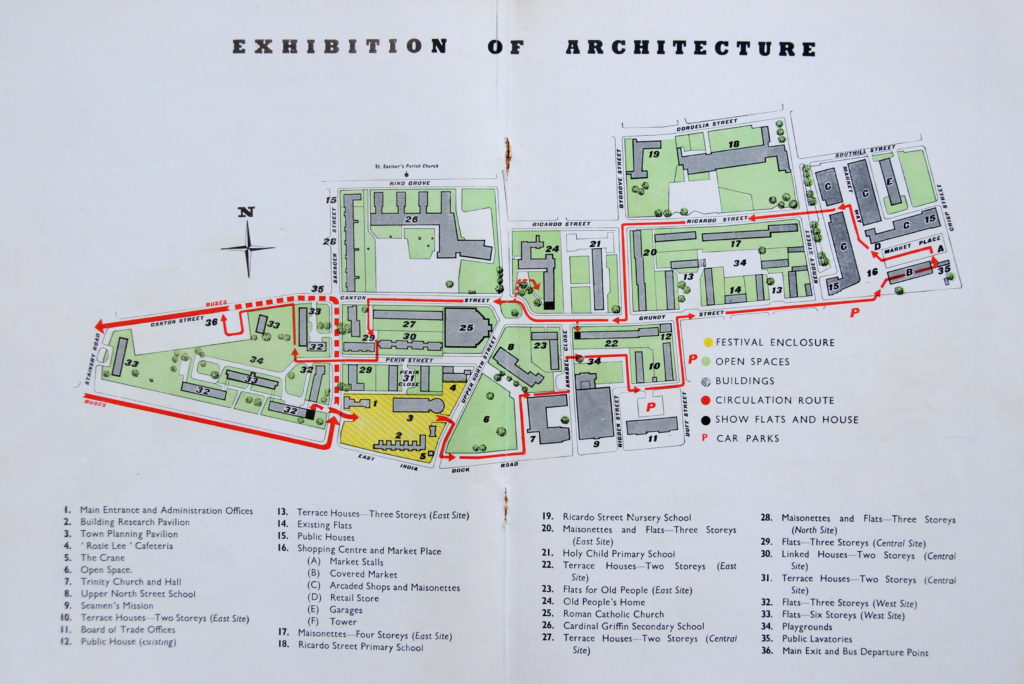

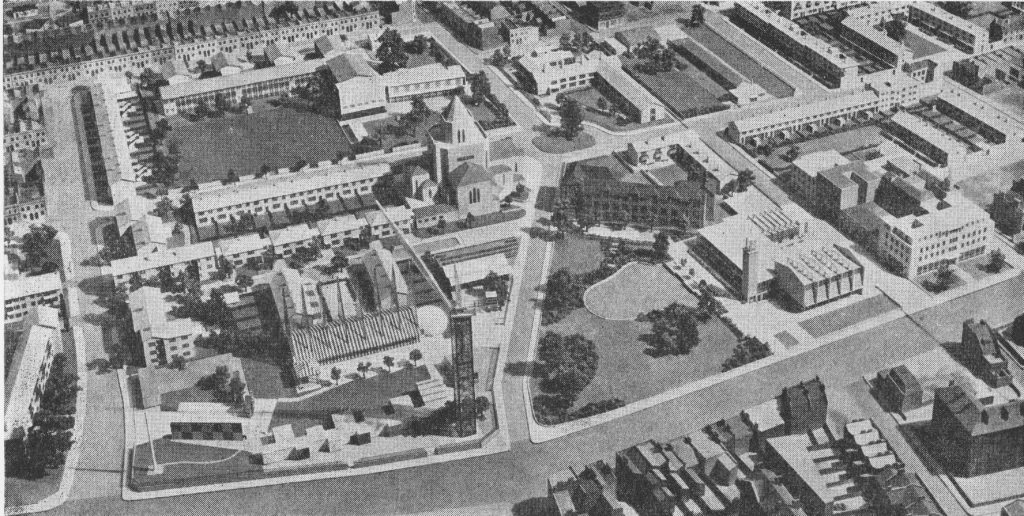

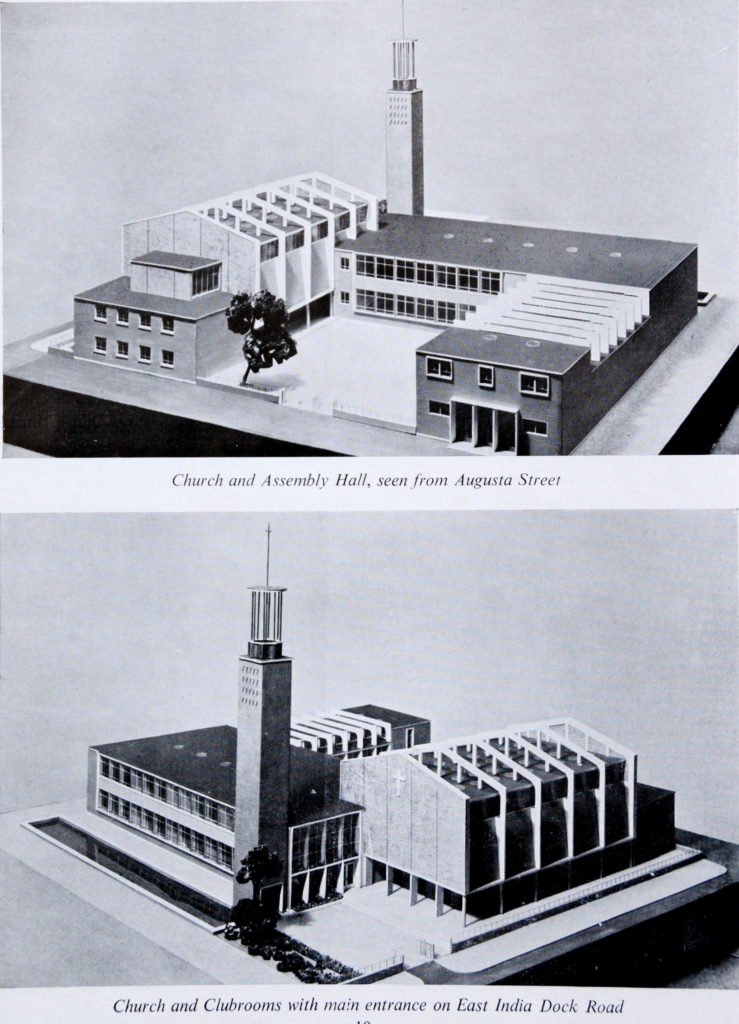

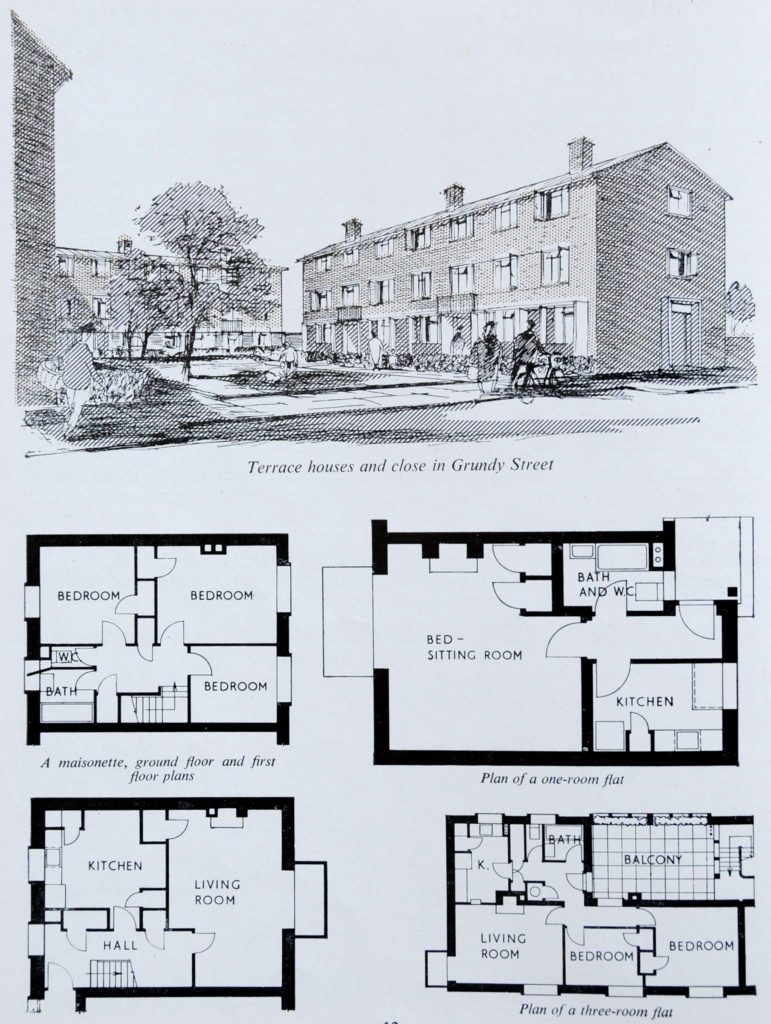

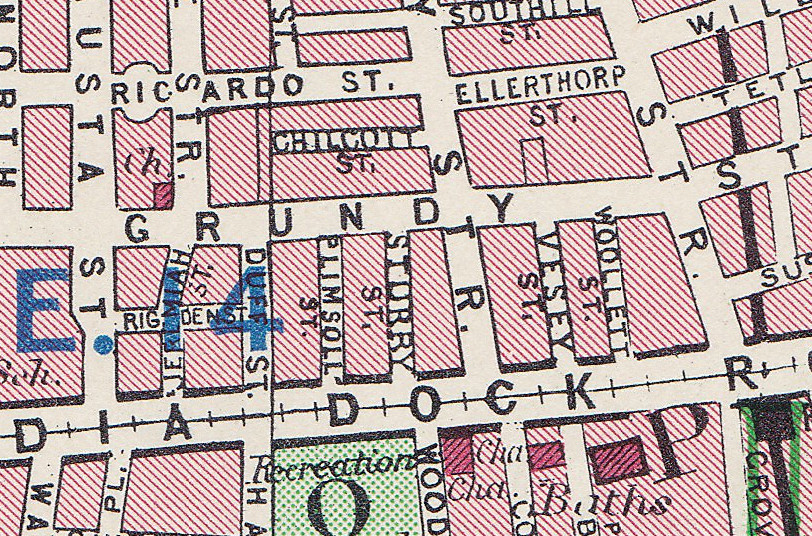

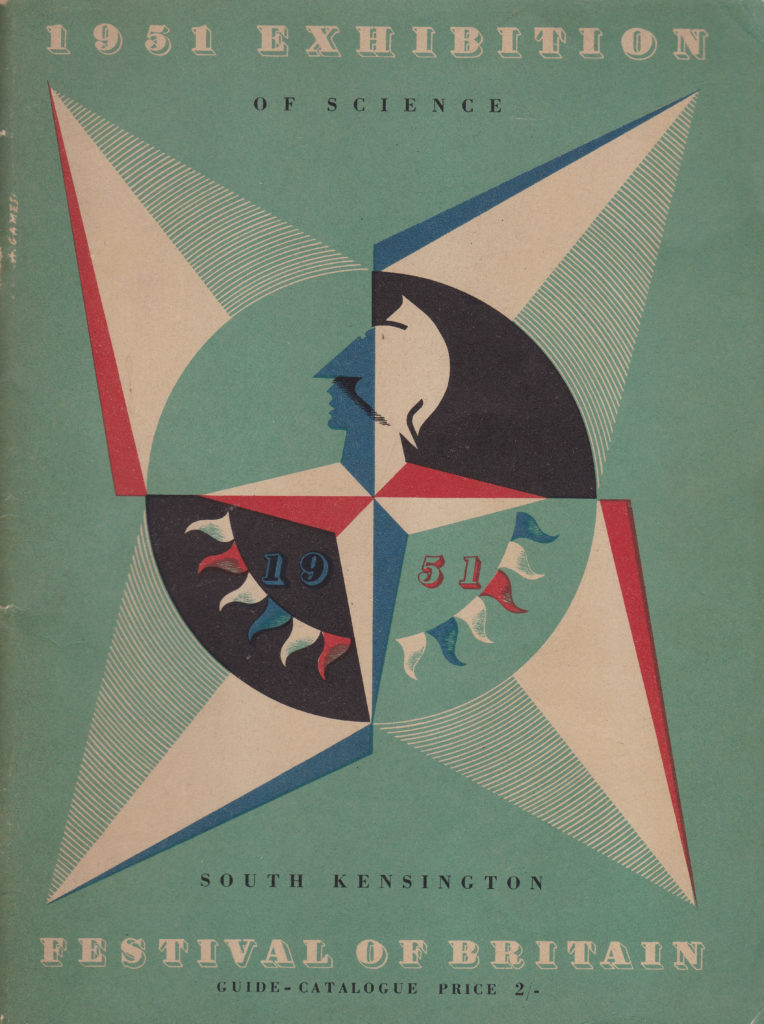

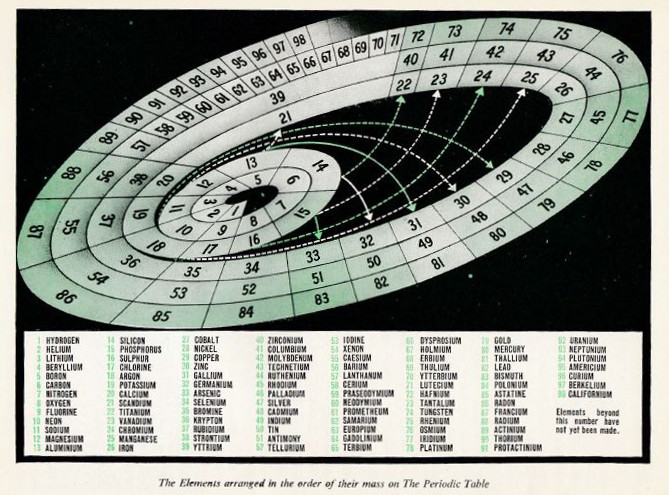

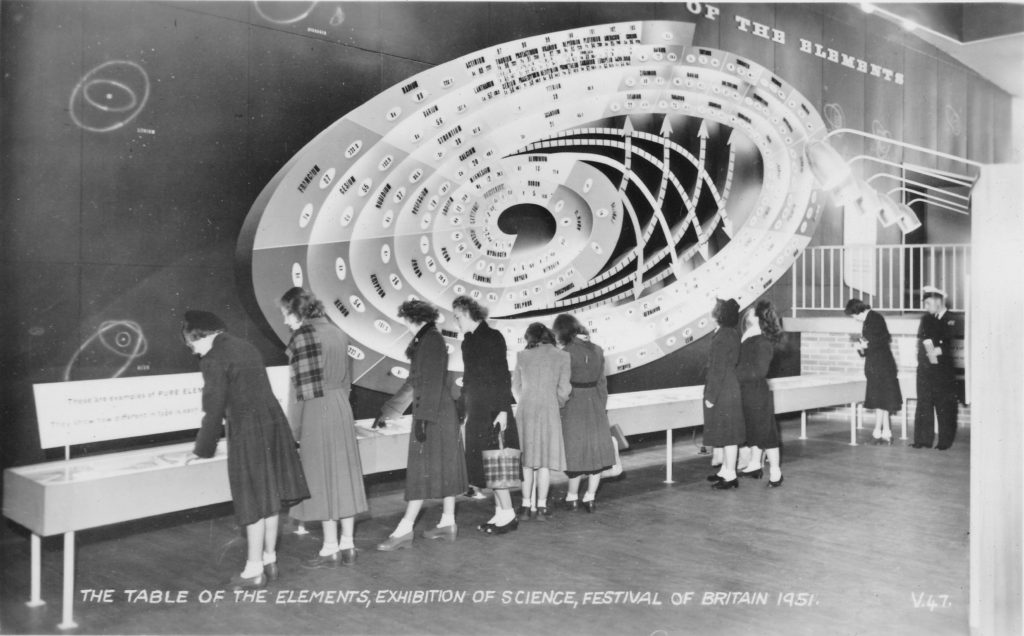

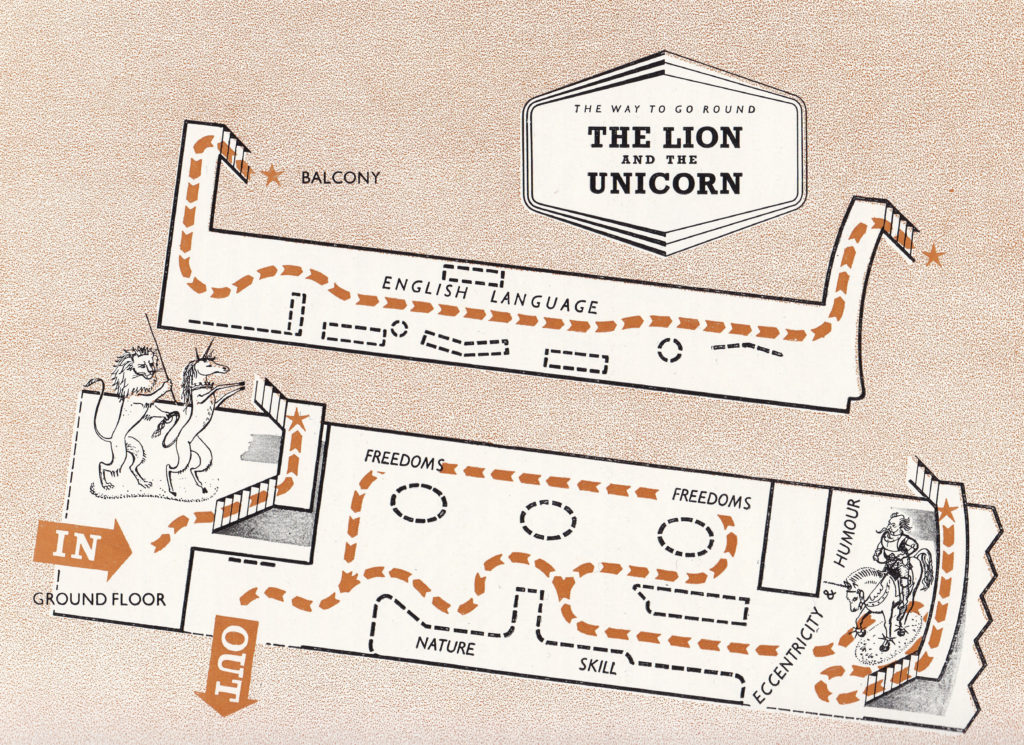

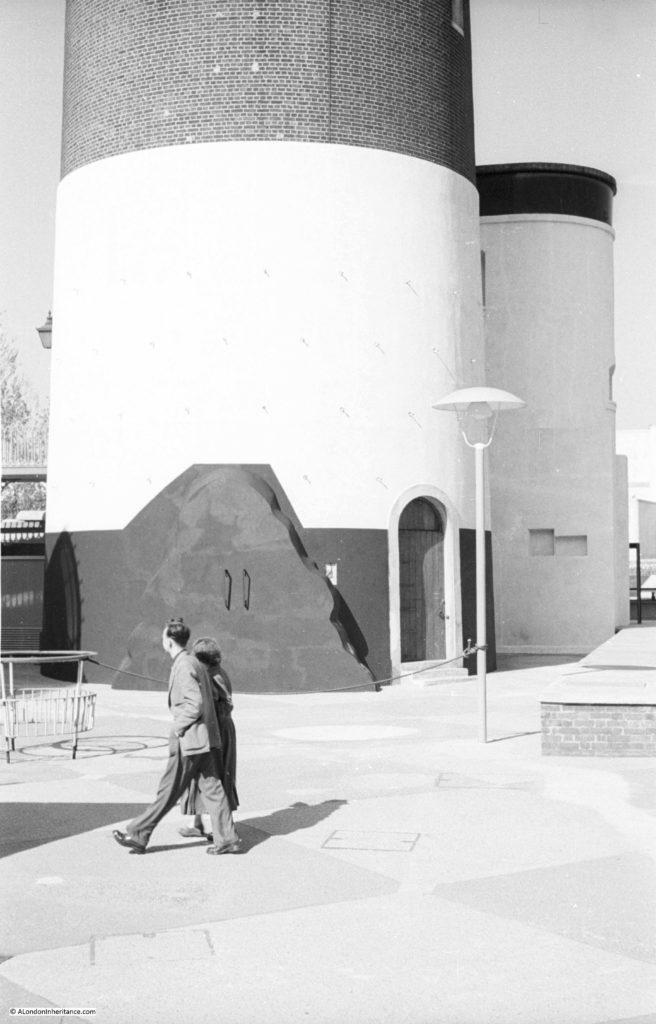

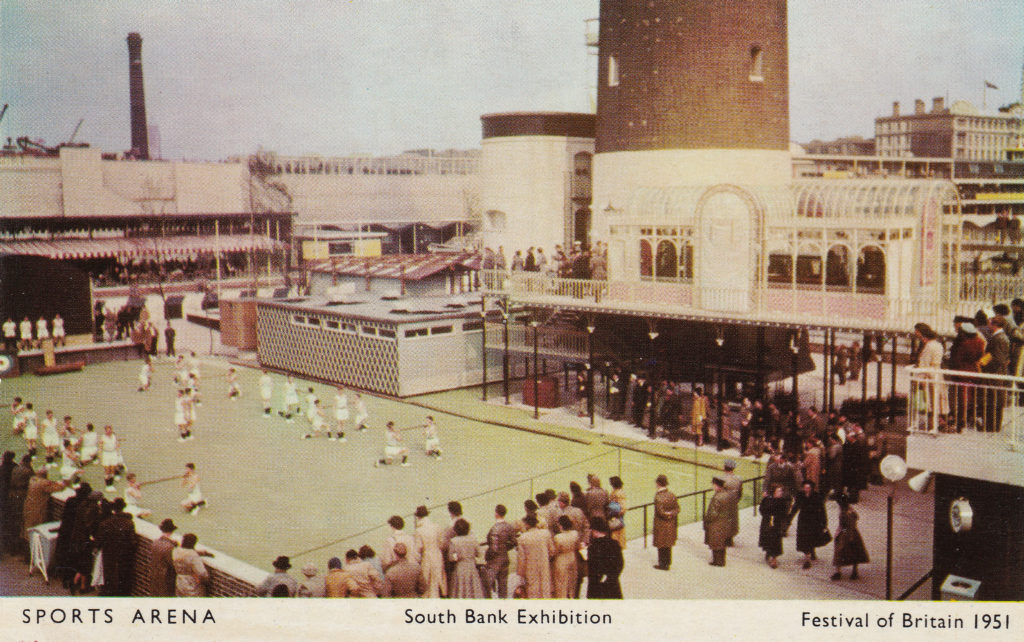

The Pleasure Gardens were where people could have some fun. The other London exhibitions, such as the main festival site on the Southbank, and the Exhibition of Architecture in Poplar, were intended to be educational and informative. To tell a story of the history of the country and the people, industry, science, design, arts etc.

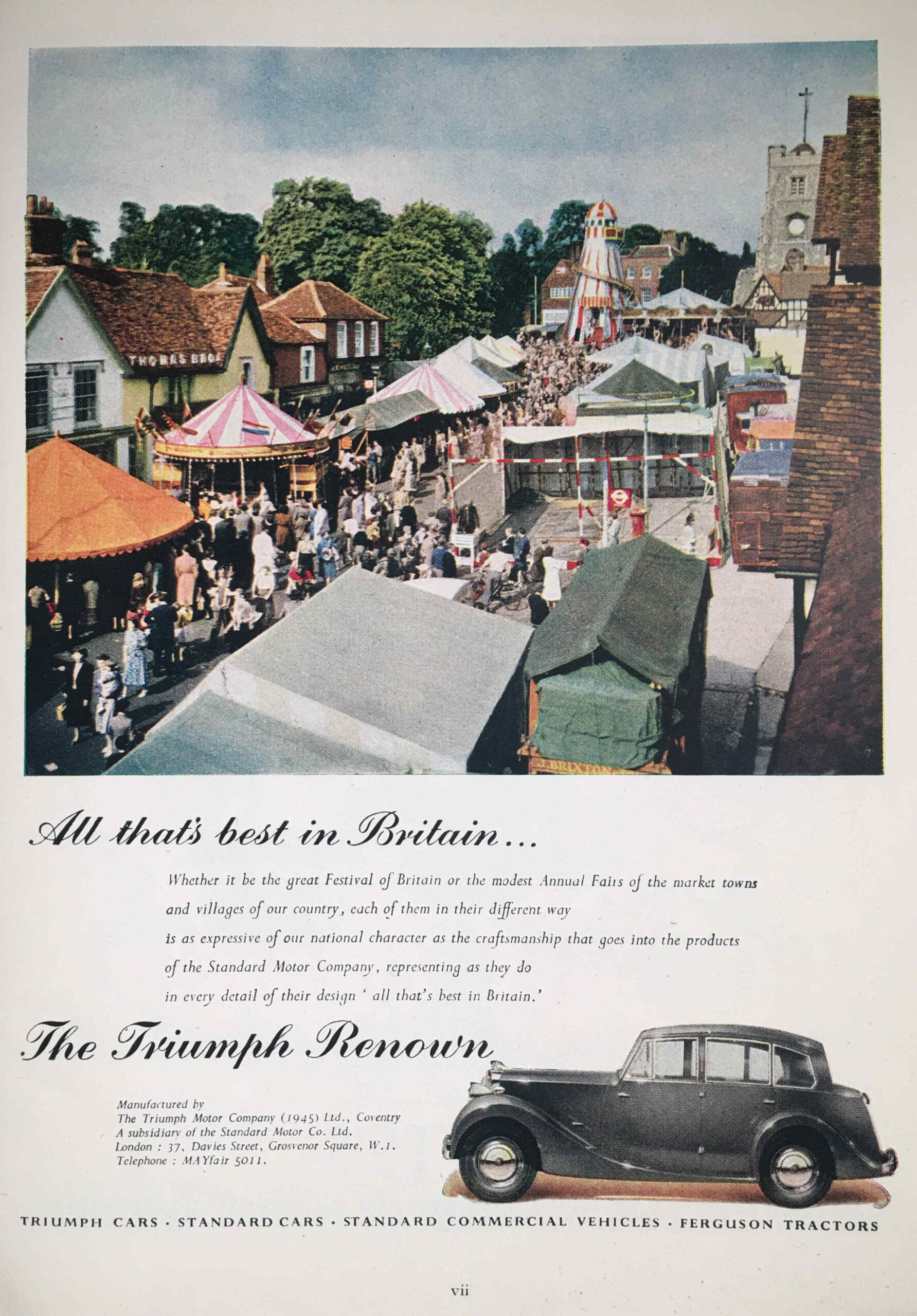

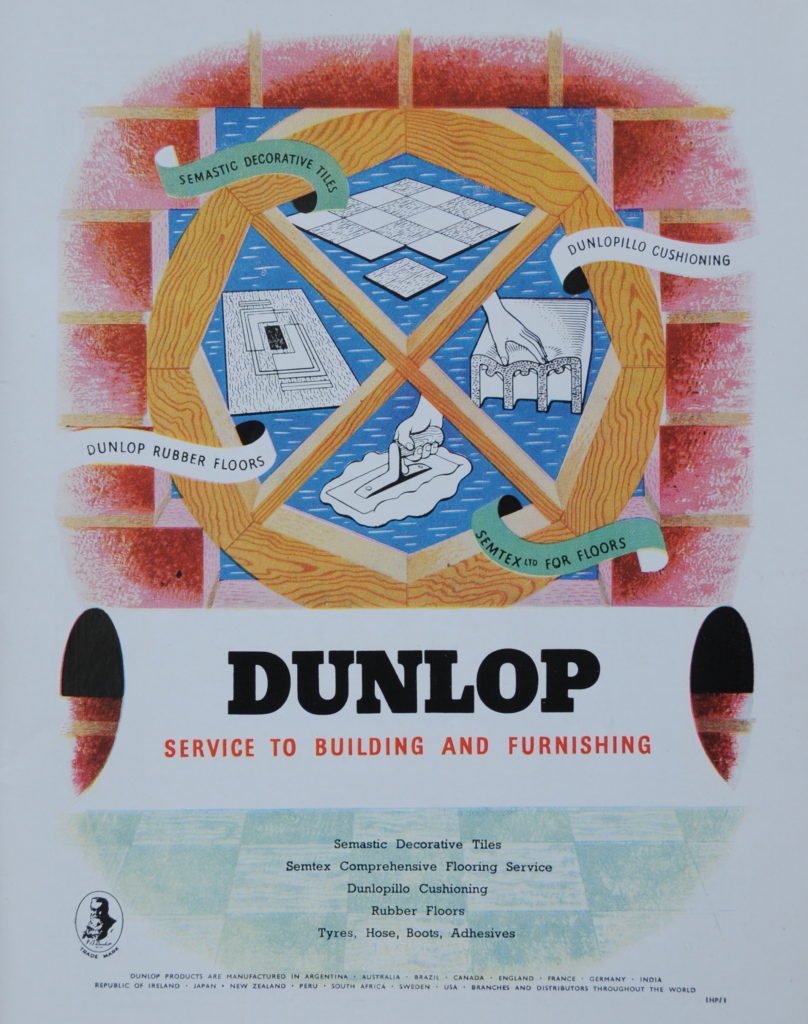

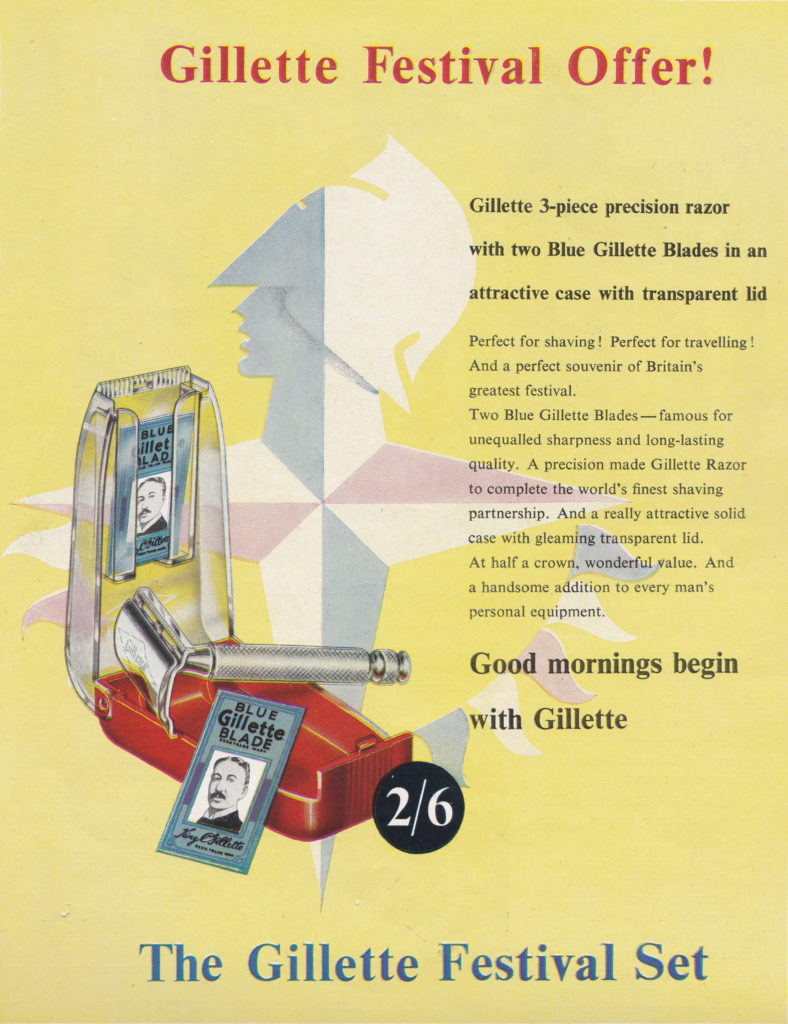

The Battersea Pleasure Gardens were also different to the rest of the festival sites, in that the Pleasure Gardens allowed commercial sponsorship, which covered not just advertising and sponsorship of places and events in the gardens, but also the provision of display items by commercial companies.

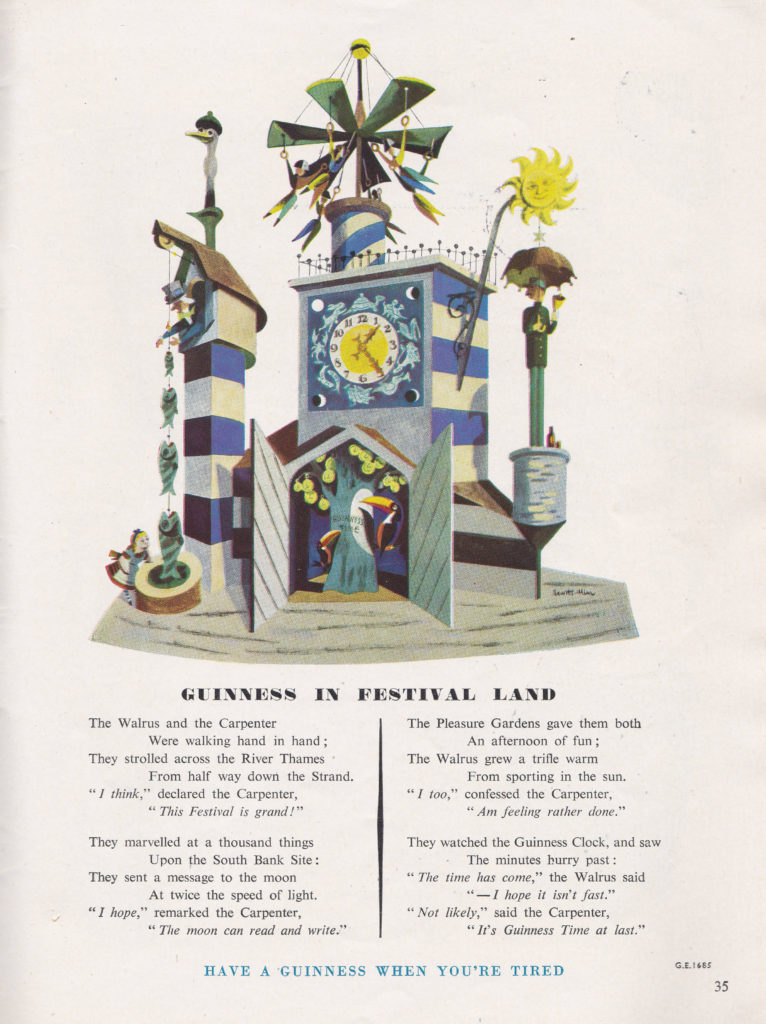

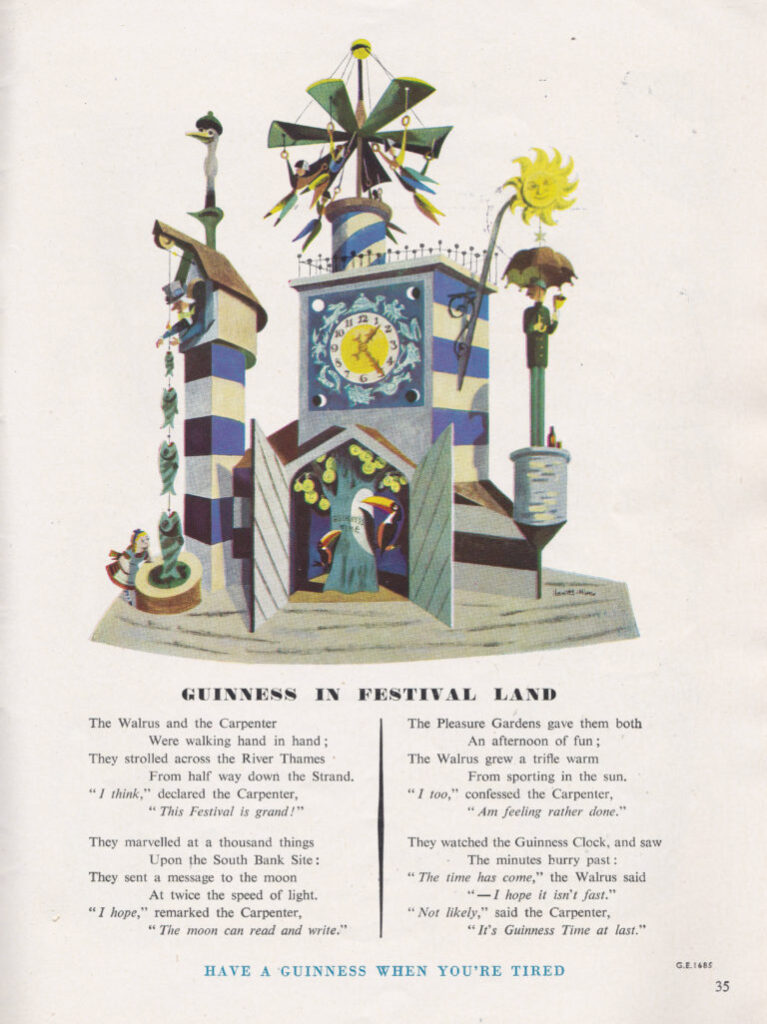

These had to go along with the general theme of the Pleasure Gardens – they had to provide some form of entertainment, fun, enjoyment, and one of the more prominent of these commercial displays was the Guinness Festival Clock:

I was recently in Ireland, which included a couple of days in Dublin, and a mandatory visit to the Guinness Storehouse, their rather impressive and very popular visitor centre in the city.

One of the floors in the centre is devoted to Guinness advertising over the years, and I was really pleased to find they had a large model of the Guinness Festival Clock:

The Guinness Festival Clock was one of the most popular attractions at the pleasure gardens. Every quarter of an hour it would burst into action with characters appearing and moving, the triangular vanes at the top opening and spinning and doors opening at the lower front to reveal the Guinness Toucan.

The Guinness Festival Clock was designed by the partnership of Lewitt-Him.

Lewitt-Him were two designers who had come to London in 1937 from Poland. Both were from Jewish families.

Jan LeWitt was born in Czestochowa in 1907. After three years travelling across Europe and the Middle East, he started work as a graphic artist and designer, and was also involved in practical activities such as machine building and in a distillery.

George Him (who had changed his name from Jerzy Himmelfarb) came from Lodz, where he was born in 1900. He had a more academic start in life, initially studying Roman Law, then obtaining a PhD in the comparative history of religions. He then began to study graphic art, and in 1933 met Jan LeWitt, and started collaborating on designs, where their style was described as being “surrealistic, cubist and with humour”.

Their move to London was possible as their work had been brought to the attention of Philip James at the Victoria and Albert Museum and Peter Gregory at the publishers Lund Humphries.

Their move to London was timely as two years later Poland was invaded by Nazi Germany, and their Jewish background would have meant almost certain death.

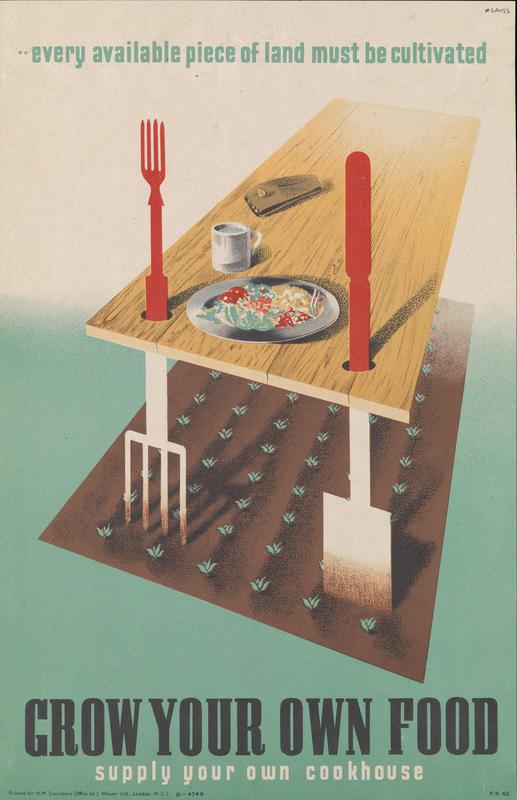

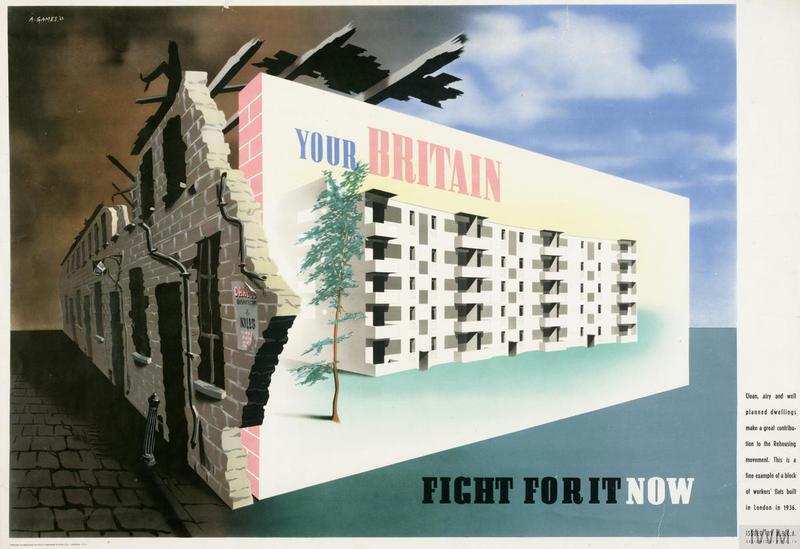

The outbreak of war also created significant demand for their skills, with the need for graphic designers to work on numerous books, posters, pamphlets and maps, many of which were in support of the war effort.

After the war, they continued to work on a wide range of projects, from commercial advertising, illustrations for books and magazines, and exhibitions.

One of the first post-war exhibitions in which they were involved was the “Britain Can Make It” exhibition in 1947 at the Victoria and Albert Museum. As with the future Festival of Britain, the 1947 exhibition was intended to show the technical and manufacturing capabilities of the country, as there was a need to dramatically increase exports and a national demand for foreign currency due to the impact of the war on the country’s finances.

The “Britain Can Make It” exhibition became known as the “Britain Can’t Have It” exhibition, as the products on display were aimed at the export market, rather than being available for domestic customers.

Four years later, and the type of design that included Lewitt-Him’s approach to surrealism and humour could be found across the Festival of Britain, with the Guinness Festival Clock being a perfect example.

The festival clock at the Guinness Storehouse is a working replica, and the following short video shows the clock in action, along with a screen to the side of the clock, showing the original Guinness Festival Clock at Battersea (if you receive the post via email, you may need to go to the website by clicking here to see the video):

The popularity of the Guinness Festival Clock was such that Guinness commissioned eight full size travelling clocks, which then travelled across Ireland and the coastal resorts of Britain. Two of these clocks were also sent to the US, so Lewitt-Him’s work for the Festival of Britain ended up providing a very successful means of advertising for Guinness.

The Guinness advert from the Guide to the Festival Pleasure Gardens included a view of the clock, and a poem about the Walrus and the Carpenter’s visit to the Southbank festival site and the pleasure gardens in Battersea:

The Lewitt-Him partnership ended in 1955, as Jan LeWitt wanted to concentrate on more artistic projects, including the design of sets and costumes for ballets held at Sadlers Wells, whilst George Him continued as a commercial graphic designer with a large portfolio of customers for his advertising work.

They both continued to be based in London, until George Him’s death in 1981 and Jan Lewitt’s death in 1991.

Now back to London, but continuing with a clock based theme.

At the junction of Fleet Street and Whitefriars Street, next to the Tipperary pub, there are two rectangular blue plaques on the curved façade of the corner building:

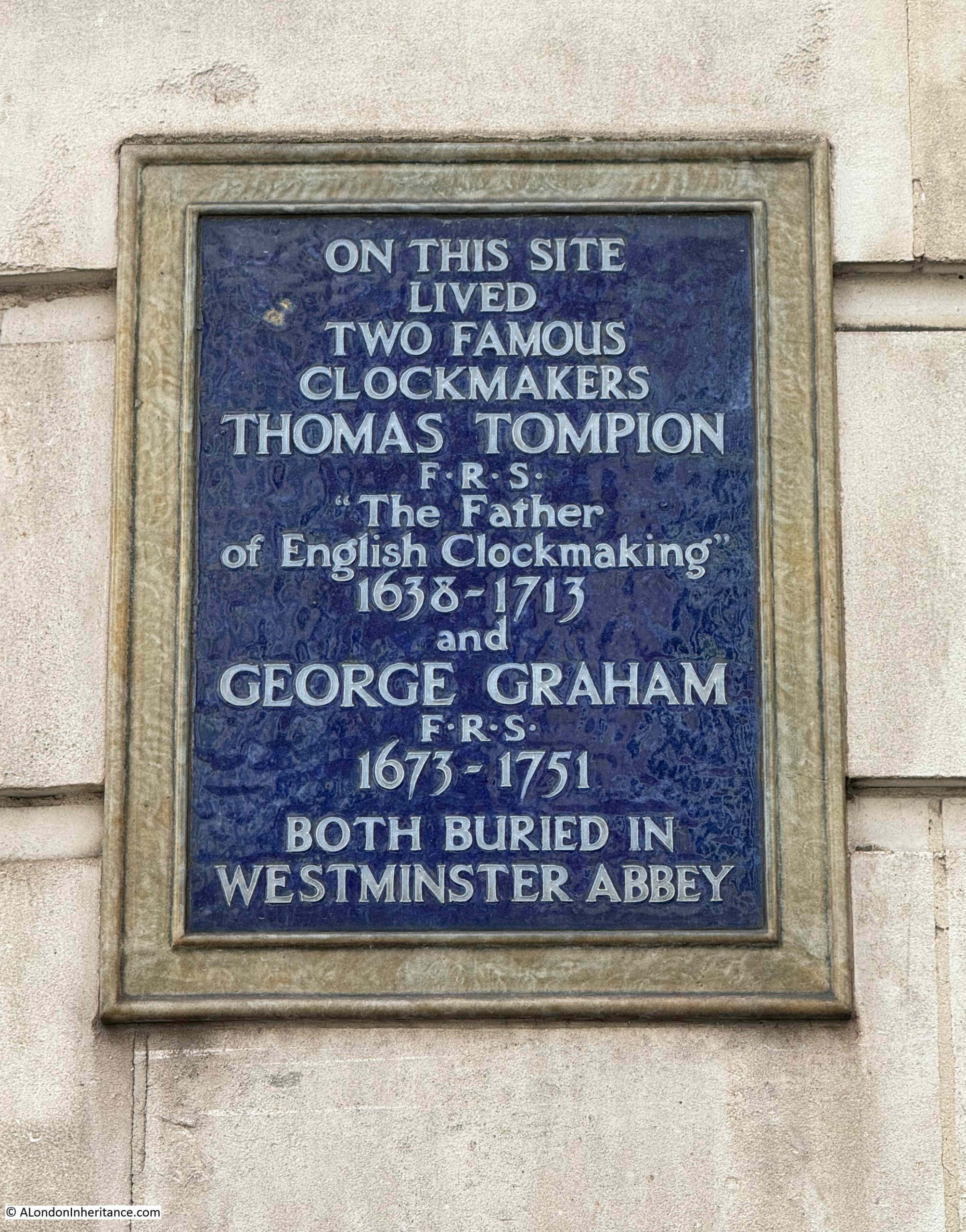

The plaque on the Fleet Street side of the building records that two famous clockmakers, Thomas Tompion and George Graham both lived at the site:

I will start with Thomas Tompion as he was the elder of the two, and was more influential in the manufacture of watches and clocks, and could be described, as stated on the plaque, as the “The Father of English Clockmaking”.

The plaque states that he was born in 1638, but the majority of sources give his date of birth as 1639, in Northill, Bedfordshire (for example Bedford and Luton Archives and Records Service, and the Science Museum). Only one year, but an example of how it is difficult to be exactly sure of dates with the distance of time, and for those who were not born into a well known and documented family.

He arrived in London in 1671, and it was his meeting with Robert Hooke three years later that would help make his name as a clockmaker.

By 1674 Tompion appears to be living and working in Water Lane, the original name of Whitefriars Street, when it ran from Fleet Street all the way down to the Thames. Strype’s 1720 description of the lane is not that flattering:

“a good broad and straight street, which cometh out of Fleet Street and runneth down to the Thames, where there is one of the City Lay-stalls, for the Soil of the Street. This Lane is better built than inhabited, by reason of its being so pestered with Carts to the Laystall and Wharfs, for Wood, Coals &c, lying by the Water side at the bottom of this lane.”

The relationship with Hooke seems to have brought Tompion plenty of information about ways of making clocks and watches, and new developments in the profession, for example, one of the mentions of Tompion in Hooke’s diary is this, from the 2nd of May, 1674 (note that Hooke calls him Tomkin in his early diary entries, but then changes to the correct spelling):

“To Tomkin in Water Lane. Much discourse with him about watches. Told him the way of making an engine for finishing wheels and a way to make a dividing plate; about the form of an arch; another way of Teeth work, about pocket watches and many other things”

Tompion, along with Hooke met King Charles II on the 7th of April, 1675, when Hooke showed the King his new spring watch which was one of Hooke’s attempts at designing a watch that would enable the calculation of longitude at sea. This required very stable time keeping, compensating for the movement of a ship and changing weather.

Charles II requested that a watch be made for him, and Tompion built the watch to Hooke’s design, however this seems to have caused a breakdown in their relationship, as Hooke was frequently complaining to Tompion that he was taking too long to finish the project.

Things did not go well after completion, as after the watch was presented to the King, he complained to Hooke that “the weather had altered the watch”. Hooke’s deign had not yet factored in temperature compensation.

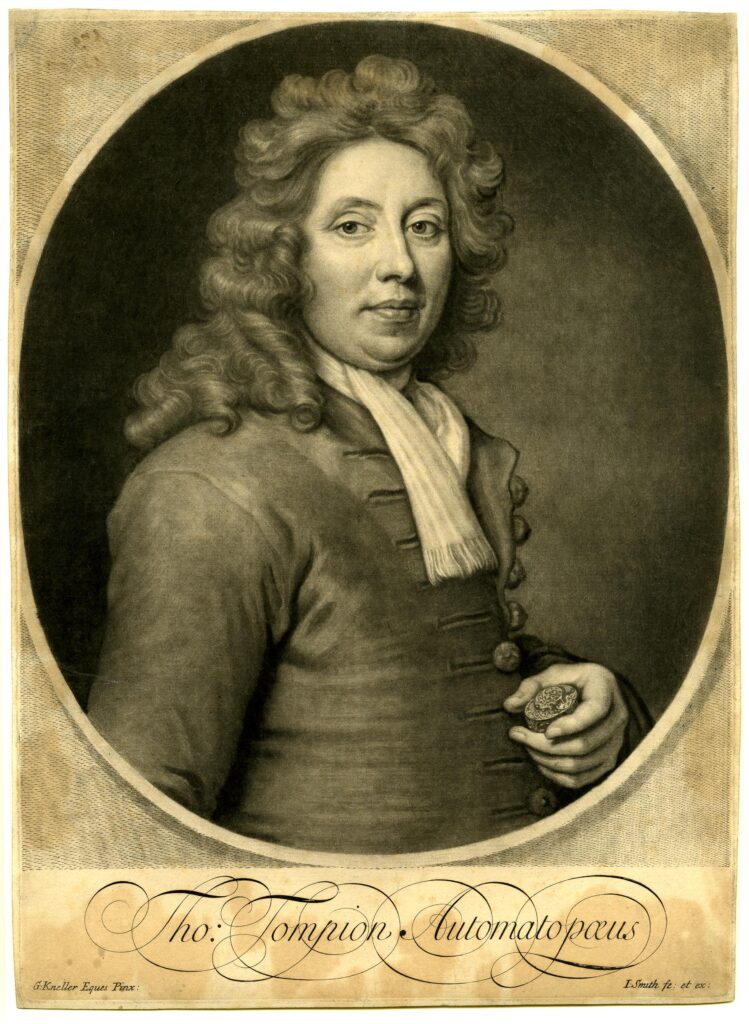

Thomas Tompion:

© The Trustees of the British Museum Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Despite any issues with the watch for the King (which appears to have been mainly Hooke’s design), Tompion’s reputation as a clock and watch maker grew rapidly. He experimented with a number of designs and manufacturing techniques to improve the reliability and accuracy of his clocks and watches, and these variations can be seen in a number of his clocks that survive.

The following watch is an example of Tompion’s work from the period 1700 to 1713:

© The Trustees of the British Museum Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The following side view provides an indication of the complexity of early 18th century watch manufacturing. For reference, the watch is just over 29 millimetres thick and the diameter of the dial is 41 millimetres:

© The Trustees of the British Museum Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

From about 1685, Tompion started to number his clocks and watches, so it is possible to estimate how many he produced. Somewhere between 4,500 and 5,000 watches and around 550 clocks.

Thomas Tompion died in 1713, and as the plaque informs, he was buried in Westminster Abbey.

His reputation as a watch and clock maker would continue for long after his death, as this advert from the Kentish Weekly Post on the 17th of June, 1732 illustrates:

“This is to give notice that all sorts of watches are made, mended and sold by Samuel Kissar, who is lately removed from St. Margaret’s-street to the Crown and Dial in Bargate-street, Canterbury.

N.B. He has a watch to sell made by Mr. Thomas Tompion, it being one of the best watches in Kent.”

An eight-day clock by Tompion from between 1695 and 1705:

© The Trustees of the British Museum Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

As Thomas Tompion became successful, he needed help in his workshops, and this led to him taking on additional staff, which is where George Graham, the second name on the plaque comes in.

George Graham started working for Tompion in 1696 when he was employed at the age of 23 as a journeyman (a trained worker), as he had already completed an apprenticeship with another clock maker, Henry Aske.

A few years earlier in 1687, Tompion had taken on Edward Banger as an apprentice.

Both Graham and Banger married in to the wider Tompion family, as George Graham married Elizabeth, who was the daughter of Tompion’s younger brother James, and Edward Banger married Margaret, the daughter of Tompion’s sister, also Margaret.

The practice of senior workers and apprentices marrying into the owner’s family seems to have been reasonably common.

George Graham became a key member of Tompion’s business and he seems to have had the same attention to detail as Tompion, as well as an approach to improvement and invention with the increasing accuracy and performance of clocks and watches.

George Graham was also a well known astronomical instrument maker as these instruments shared many features with clocks and watches where metal working was needed, with instruments built with increasing accuracy (whether measuring time, or the position of a star in the sky).

As far as I can tell, Thomas Tampion died without having had any children who could take over the business. He left the business to George Graham, who announced this in the London Gazette in December 1713: “George Graham, nephew of the late Mr. Thomas Tompion, who lived with him upwards of seventeen years and managed his trade for several years past, whose name was joined with Mr. Tompion’s for some time before his death, and to whom he had left all his stock and work, finished and unfinished, continues to carry on the said trade at the late Dwelling House of the said Mr. Tompion, at the sign of the Dial & Three Crowns, at the corner of Water Lane, in Fleet Street, London, where all persons may be accommodated as formerly.”

Seven years later, George Graham moved a short distance, and announced in the London Gazette in March 1721: “George Graham, watchmaker is removed from the corner of Water Lane, in Fleet Street, to the Dial & One Crown on the other side of the way, a little nearer Fleet Bridge, a new house next door to the Globe and Duke of Marlborough’s Head Tavern”.

What is interesting with these announcements is the description of the place where George Graham was located. They are all graphical descriptions where the names that would have been on the signs at or next to Graham’s location are given.

The following image shows three of George Graham’s long case clocks, made between 1740 and 1750:

© The Trustees of the British Museum Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The pendulum can be seen in the clock on the right, and the type of pendulum was one of George Graham’s inventions – the mercurial compensated pendulum.

Using mercury at the base of a pendulum was a clever method to compensate for temperature variations.

With an all metal pendulum, when the temperature rises, the pendulum expands and gets longer, which impacts the accuracy of the clock.

When a glass vial is at the bottom of the pendulum, the pendulum rod still expands making it longer, however the mercury in the glass vial responds to the increase in temperature by rising up the glass vial, and because mercury is a heavy mass, the rise in the height of mercury against a lengthening pendulum, keeps the overall centre of gravity at the same place, so the clock continues to keep time as temperature changes.

In 1721 George Graham was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society and in 1722 he was elected as Master of the Clockmakers Company, and as well as clocks and watches, he continued to work on astronomical instruments, and other scientific instruments such as a micrometer.

George Graham died in 1751, and the following is a typical newspaper report of his death: “Last Saturday Night died, in the 78th Year of his Age, that great Mechanic Mr. George Graham F.R.S. Watchmaker in Fleet-street, who may be truly said to have been the Father of the Trade, not only with regard to the Perfection to which he brought Clocks and Watches, but for the great Encouragement of all Artificers employed under him, by keeping up the Spirit of Emulation among them.”

After his death, George Graham was buried in the same grave as Thomas Tompion in Westminster Abbey.

Although the plaque states that Thomas Tompion was the “Father of English Clockmaking”, the reports that followed the death of George Graham described him as the “Father of the Trade”.

I do not think there needs to be any competition, both Tompion and Graham seem to have been equals in their craft, and their ability to improve and invent clocks and watches.

There is a second plaque on the corner of the building, and the following photo shows the plaque on the Whitefriars Street side of the building:

The Corn Laws were a set of laws implemented in 1815 by the Tory Prime Minister Lord Liverpool due to the difficult economic environment the country was in following the wars of the late 18th and early 19th century.

The Corn Laws imposed tariffs on imported grains and resulted in an increase in the price of grain, and products made using grain. These price increases made the Corn Laws very unpopular with the majority of the population, although large agricultural land owners were in favour as they made a higher profit from grain grown on their lands.

The Corn Laws were finally repealed by the Conservative Prime Minister Robert Peel in 1846, and they reflect a tension between free trade, and tariffs on imports that can still be seen in politics today.

John Bright was born on the 16th of November, 1811 and was the son of a Quaker textile manufacturer in Rochdale. Having been born into a Quaker family, Bright became involved with the type of political causes favoured by nonconformists.

Bright met Richard Cobden in 1835 and in 1840 he became treasurer of the Rochdale branch of the Anti-Corn Law League. Bright was a gifted public speaker, and in the campaign to repeal the Corn Laws he would travel across the country speaking and campaigning for the cause.

He was an MP for Durham, then Manchester and finally Birmingham. After the repeal of the Corn Laws, Bright continued to campaign for free trade, including a commercial treaty with France, which resulted in the1860 Cobden-Chevalier Treaty which lowered customs duties between the two countries.

Richard Cobden was born on the 3rd of June, 1804 in a farmhouse in Dinford, near Midhurst in Sussex. His only time in London appears to have been after his father died, when Cobden was still young, and he was taken under the guardianship of his uncle who was a warehouseman in London.

Not long after he became a Commercial Traveler, and then started his own business which was based in Manchester, which seems to have been his base for the rest of his commercial success.

During his time in Manchester Cobden was part of the Anti-Corn Law League and was known as one of the leagues most active promoters.

The blue plaque on the corner of the building states that “On the site were situated the offices on the Anti-Corn-Law-League with which John Bright and Richard Cobden were so closely associated”.

What is not clear is how much time they spent in London, and in the offices of the anti-corn-law-league, so if anything, the plaque is recording a political campaign for free trade rather than the place of residence or work for two 19th campaigners.

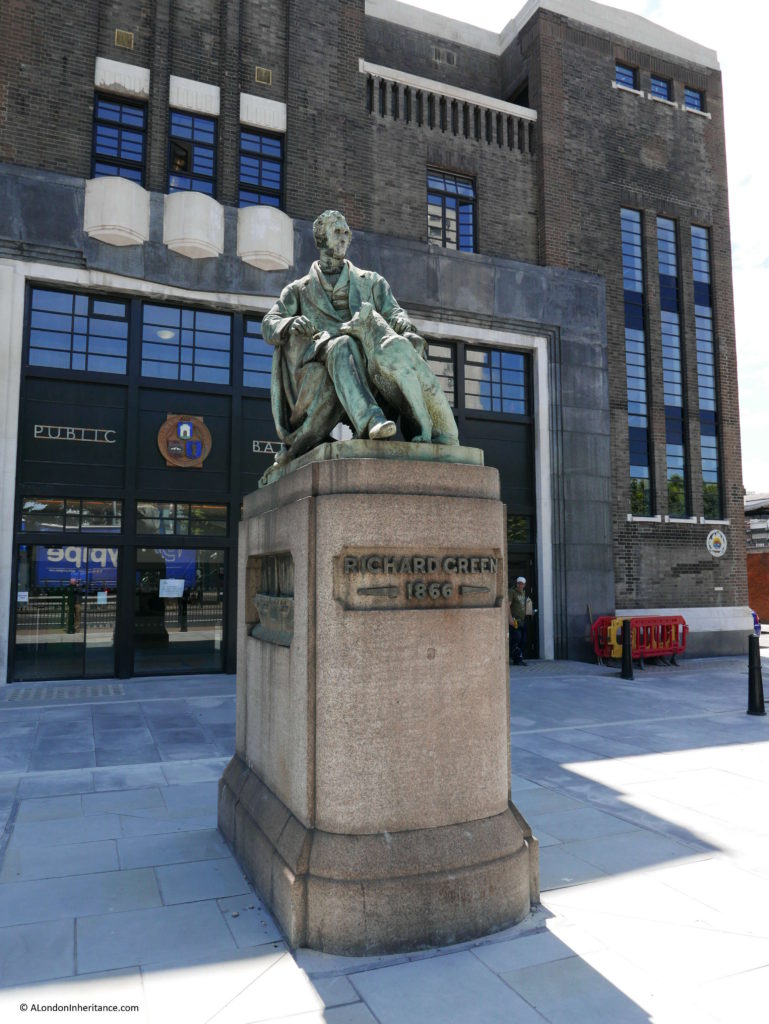

Richard Cobden does have a statue in Camden, opposite Mornington Crescent underground station, but again this seems to championing free trade and Cobden’s role in the repeal of the corn laws:

The Clerkenwell News and London Times on the 1st of July 1868 recorded the unveiling of the statue:

“The Cobden memorial statue which has just been erected at the entrance to Camden Town was inaugurated on Saturday. Although this recognition of the services of the great Free Trade leader may have been looked upon in some quarters as merely local, the gathering together of some eight to ten thousand people to do honour to his memory cannot be regarded in any other light than that of a national ovation.

The committee had arranged that the statue of the late Richard Cobden at the entrance to Camden Town – with the exception, perhaps, of Trafalgar Square, one of the finest sites in London – should be unveiled on Saturday, that day being understood to be the appropriate one of the anniversary of the repeal of the Corn Laws, and the event was so popular that the surrounding neighbourhood was gaily decorated with flags for the occasion. The windows and balconies of Millbrook House, the residence of Mr. Claremont, facing the statue, had been placed at the disposal of Mrs. Cobden and her friends, including her three daughters.

A special platform had been created in front of the pedestal, covered with crimson cloth, and in the enclosure in front the band of the North Middlesex Rifles were stationed, and performed whilst the company assembled.

The report then covers at some length, all the speeches made which told the story of Cobden’s life and his actions in the repeal of the Corn Laws. There were many thousands present to witness the event, and at the end; “after the vast assembly had dispersed Mrs. Cobden, accompanied by Mr. Claremont, the churchwardens, and other friends, walked round the statue and expressed her high gratification at the fidelity of the likeness.”

Before I leave this small area of Fleet Street, there are a couple of major developments underway. In the following photo, the building with the two plaques on the corner is at the right side of the photo, one of the plaques can just be seen. Opposite is a very large building site:

This area is set to become a so called new Justice Quarter in the City, and the area will comprise:

1 – New City of London Law Courts

2 – New headquarter building for the City of London Police

3 – Public space covering an area slightly larger than the current Salisbury Square

4 – New commercial / office space with, you may have guessed, space for restaurants, bars or cafes on the ground floor

I photographed the area before the buildings that were on the site were demolished in a 2021 post on “Three Future Demolitions and Re-developments” which can be found by clicking here.

A bit further along Fleet Street, towards Ludgate Circus, the building next to the old Daily Express building has been demolished, leaving a view of the side of the Express building, and to the buildings at the rear – a temporary view that will soon disappear:

A mix of different subjects in this week’s post, but a very tenuous clock based link with the Guinness clock and two 17th / 18th century London watch and clock makers – all part of London’s deep history, and how you can find unexpected examples of that history in the most unexpected places, such as a brewery in Dublin.