My last post on the Exhibition of Architecture was rather long and there were still a number of things I wanted to include on the subject, so here is my very final post on the Festival of Britain.

Firstly, a couple of stills from a children’s film made in 1956. The film is “One Wish Too Many” and many of the external shots were filmed in and around the Lansbury estate. The film tells the story of a boy who finds a magic marble with rather unpredictable results.

The film can be found here. In my last post I mentioned the pole mounted scene of people around a model of the Skylon. This appears in the film and a still showing the pole is below:

The Chrisp Street market also features in the film:

One Wish Too Many is a fascinating film to watch for a glimpse of the area as it was 60 years ago, and to see how life in Poplar was portrayed in film.

As well as the Exhibition of Architecture at Lansbury, the Council of Architecture advising the organisers of the Festival of Britain recommended that there be an award for “contributions to civic or landscape design, including any buildings, groups of buildings or improvement to the urban or rural scene“.

The idea of an award was approved and entries were invited. There were challenges with getting a sufficient number of entries as building work had to have been started by the end of the war with completion in time for the award judging and the Festival of Britain. The initial end date for entries of September 1950 was extended to March 1951 to provide additional time.

Winners of the award would receive a plaque with the festival symbol. There are a number of these that can still be seen today, one being at White City Underground Station. The plaque at the station is shown in the photo below. The plaques were made by Poole Pottery and consisted of a matt blue slip covering the base of the plaque with the festival symbol, festival year and lettering around the edge of the plaque raised, and painted white.

White City station was designed by A.D. McGill and Kenneth J.H. Seymour for Thomas Bilbow of London Transport. This station served the nearby White City Stadium and therefore had to manage large crowds. The station had extended platforms and a separate “rush hall” providing additional space into and out of the station when there was an event on at White City Stadium. Additional space to the right of the main entrance provided accommodation and working space for train crews.

White City Station as it is today. The festival plaque is just to the left of the main entrance.

There were 19 winners of the festival award. As well as White City, other London winners included:

- in Pimlico, Chaucer House, Coleridge House, Shelley House and Pepys House with the hot water accumulator fed from Battersea Power Station

- the Somerfield Estate in Dalston

- Newbury Park Bus Station

- Heath Park Estate, Dagenham

Winners outside of London included an Old People’s Home in Glasgow and a School in Stevenage. It would be an interesting exercise to track down the 19 winners and see if the buildings are still there along with their plaques and how their 1951 design has survived over the past 65 years.

Back in Poplar, it is always interesting to walk an area – there is always much to find.

At the junction of Chrisp Street and Susannah Street there is the mosaic from the entrance of a branch of “Burton – the Tailor of Taste” that was originally at this location.

Almost directly across Chrisp Street from the above mosaic is this giant mural created in 2014 by the street artists Irony and Boe on one of the 1960s buildings between the market and the East India Dock Road. A giant chihuahua welcoming drivers heading into London.

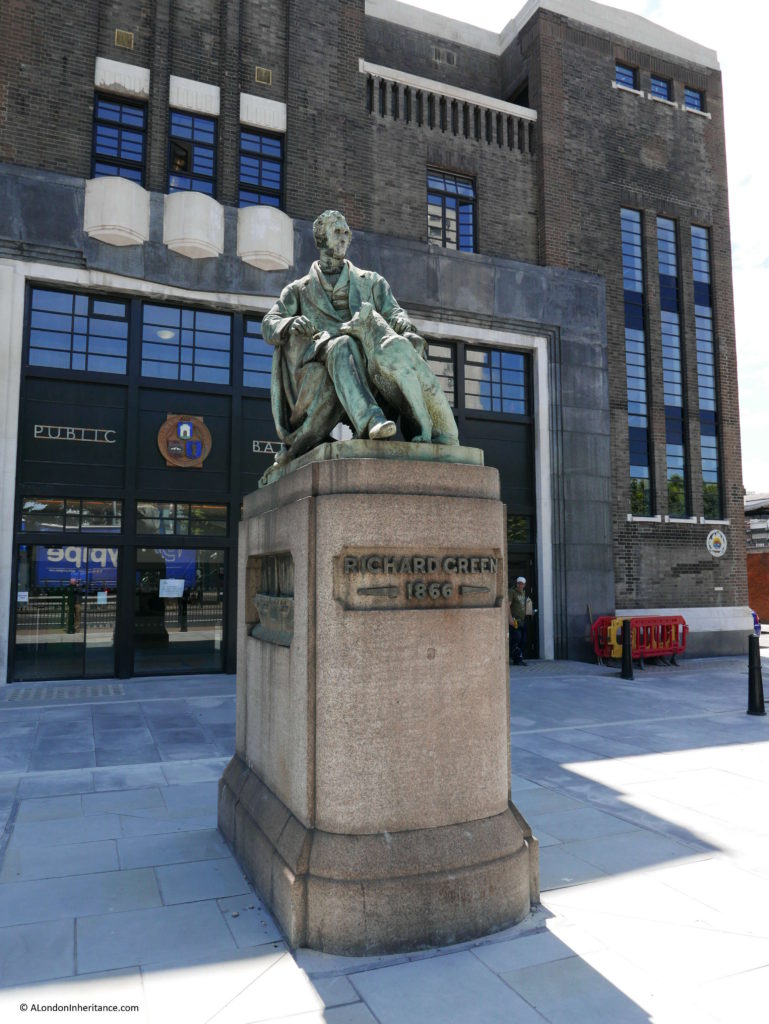

On the opposite side of the East India Dock Road to Chrisp Street is this statue to Richard Green.

Green owned a shipyard in Blackwall. He support the Poplar Hospital, a Sailors Home, he founded the Merchant Service training ship, HMS Worcester and was active in forming the Royal Naval Reserve. He died in 1863, the year 1866 on the plinth refers to the year in which the statue was erected on this spot.

What caught my eye with this statue are that on either side of the plinth are some carvings of ships associated with Richard Green. On the western facing side of the plinth is a frigate under construction for the Spanish Government at Green’s yard.

And on the east facing side of the plinth is the first ship sent from Green’s Blackwell boatyard to China.

Further along East India Dock Road, on the Lansbury side are two buildings that were on the original Lansbury guidebook map (see my previous post). The first is the Queen Victoria Seamen’s Rest – marked number 9 on the map. Originally established as the Seamen’s Mission of the Methodist Church in 1843 with buildings in the adjacent Jeremiah Street, the present buildings facing onto the East India Dock Road are the 1950’s extension to the original buildings. Still in operation and providing support and accommodation to ex-seamen, ex-servicemen and others in need of accommodation.

Next along are the buildings marked as number 11 on the map. At the time they were Board of Trade Offices but are now flats. The cream coloured paint, fine weather and style gives the buildings an appearance of colonial architecture.

As with the other Festival of Britain guide books, the one for the Exhibition of Architecture has a fascinating selection of adverts related to the subject of the exhibition.

I find these interesting for a number of reasons – the subject of the advert, the company, the advertising style and the use of colour. Here are a selection from the guide.

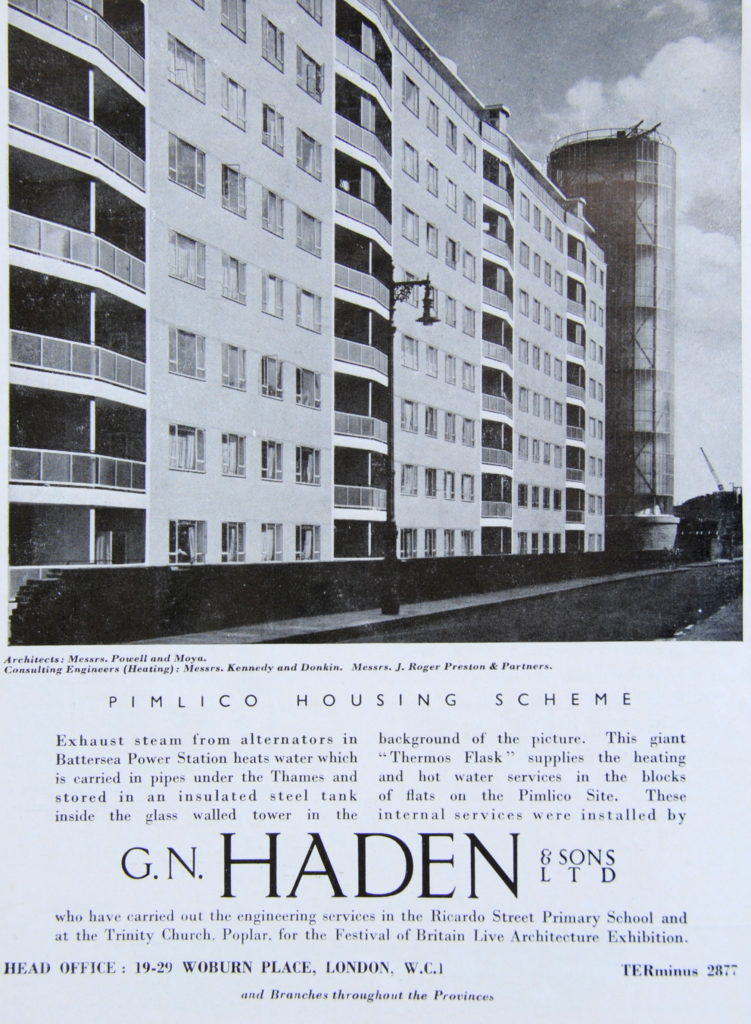

The first is for the company G.N. Haden, a firm of electrical and mechanical engineers who worked on a couple of the Lansbury sites, however the advert is for the district heating system in Pimlico that used hot water from Batterea Power Station. G.N. Haden went through a number of mergers until eventually becoming part of Balfour Beatty.

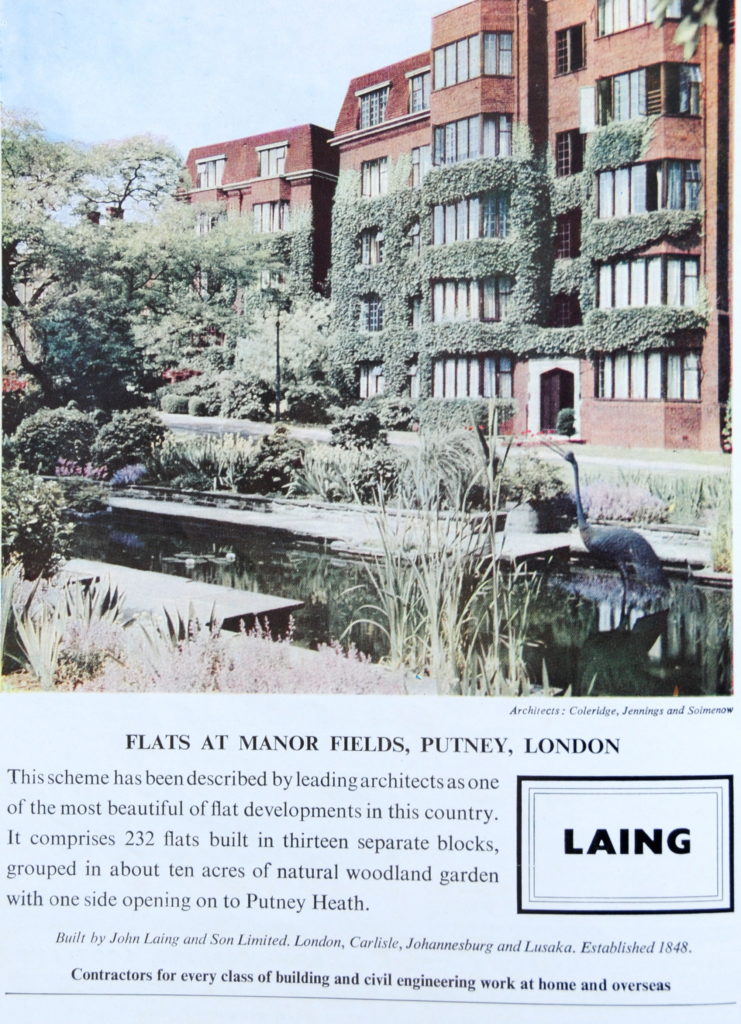

The Manor Fields private estate in Putney, built by Laing. The estate still looks much the same today.

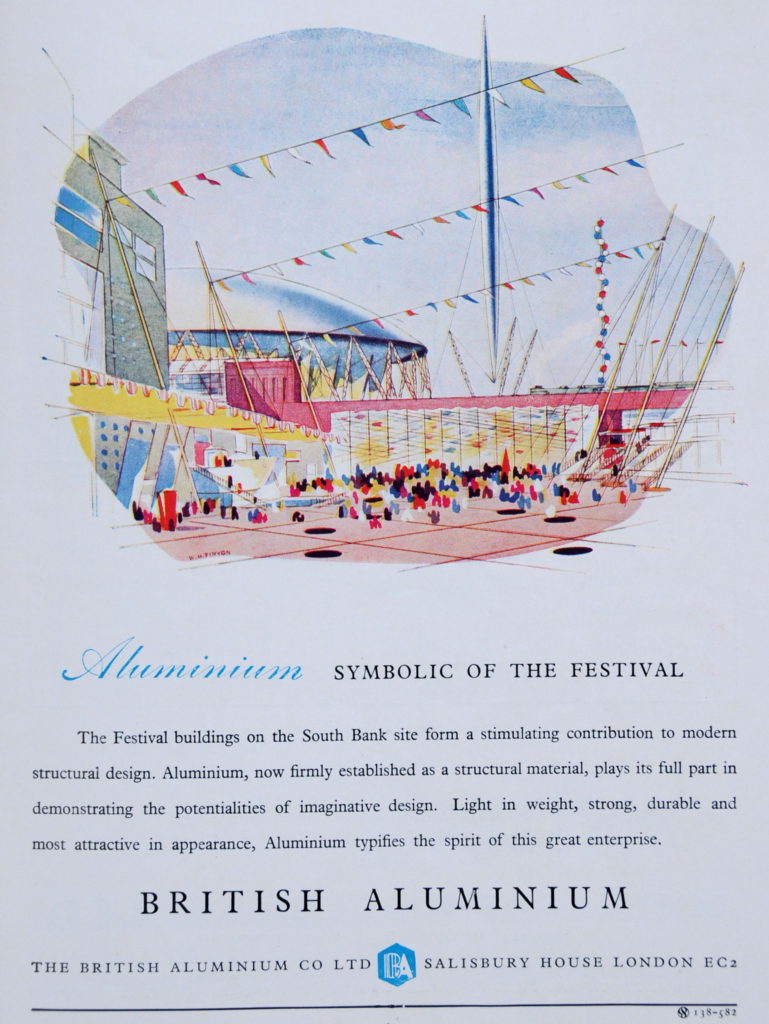

The Dome of Discovery on the South Bank was the largest aluminium building in the world at the time of the festival. British Aluminium was the country’s largest producer and as the process of producing aluminium consumed large amounts of electricity, plants would make use of new hydro-electric and nuclear products over the coming years, however global over production and higher production costs in the UK caused continual problems and the company was purchased and split over time between a number of global producers and private equity. None of the original production plants remain.

Sissons – Hull based paint manufacturers. Cannot find too much about them, however I believe they were finally integrated into Akzo-Nobel and all the Hull based manufacturing operations closed.

Dunlop – probably better known for the company’s tyre production, Dunlop was a major British multi-national, however lack of innovation with tyre products allowed competitors to gain market share with new products. Production and quality issues, debts from failed global partnerships resulted in a common story for British industry during the final decades of the 20th century of company break-up, ongoing selling through a number of owners and closure of plants and parts of the business. How different it must have seemed in 1951.

Creda and Simplex, both at the time owned by the conglomerate TI (Tube Investments).

TI went through a range of difficulties resulting in the sale of individual businesses and brands. Creda was still operating as a brand, but is now integrated into Hotpoint. The advert features the Creda Comet “the last word in electric cookery”.

Broadcrete lighting columns made by Tarslag who as the name implies were mainly a road surfacing company. Soon after this advert appeared, Tarslag sold the designs of the Broadcrete lighting columns to Concrete Utilities – an established company already producing concrete lamp posts and the Broadcrete designs soon stopped production so I suspect they are now rather rare. Concrete Utilities, now known as CU Phosco continues as a UK manufacturer of lighting equipment, however now producing metal products rather than concrete. Much of the street lighting across London is manufactured by CU Phosco.

Tarslag was eventually purchased by Tarmac.

I am not sure whether the Tarslag Broadcrete lamp-post is a fitting conclusion to my series of posts on the Festival of Britain, but it does highlight how the optimistic view of the future presented during the festival would change dramatically over the coming decades.

I realise I have only been able to scratch the surface of this subject, not just about the Festival, but also how the Festival reflected the country as it was at the start of the 1950s – both London and the country have changed dramatically in the 65 years since.

There are many excellent books on the Festival of Britain – see the end of this previous post for a list.

Thank you for putting up with my interest in the Festival of Britain, starting next week, a completely different series of posts.

iworked for green& siley weir at blackwall yard the last drydocks( 2 of) and ship repair in london

Yes, the Barclay School in Stevenage is still there – the first new purpose-built secondary school constructed in England after the Second World War. It is Grade II listed now, and still has the “Family Group” scupture made for it by Henry Moore.

Good to see two different works of architects Philip Powell and Hidalgo Moya on this page. They designed the Festival of Britain’s Skylon and the Pimlico Housing Scheme’s Churchill Gardens Estate.

Very interesting. Queen Adelaide Court in Penge designed by Edward Armstrong was also a winner and the plaques are still clearly displayed.