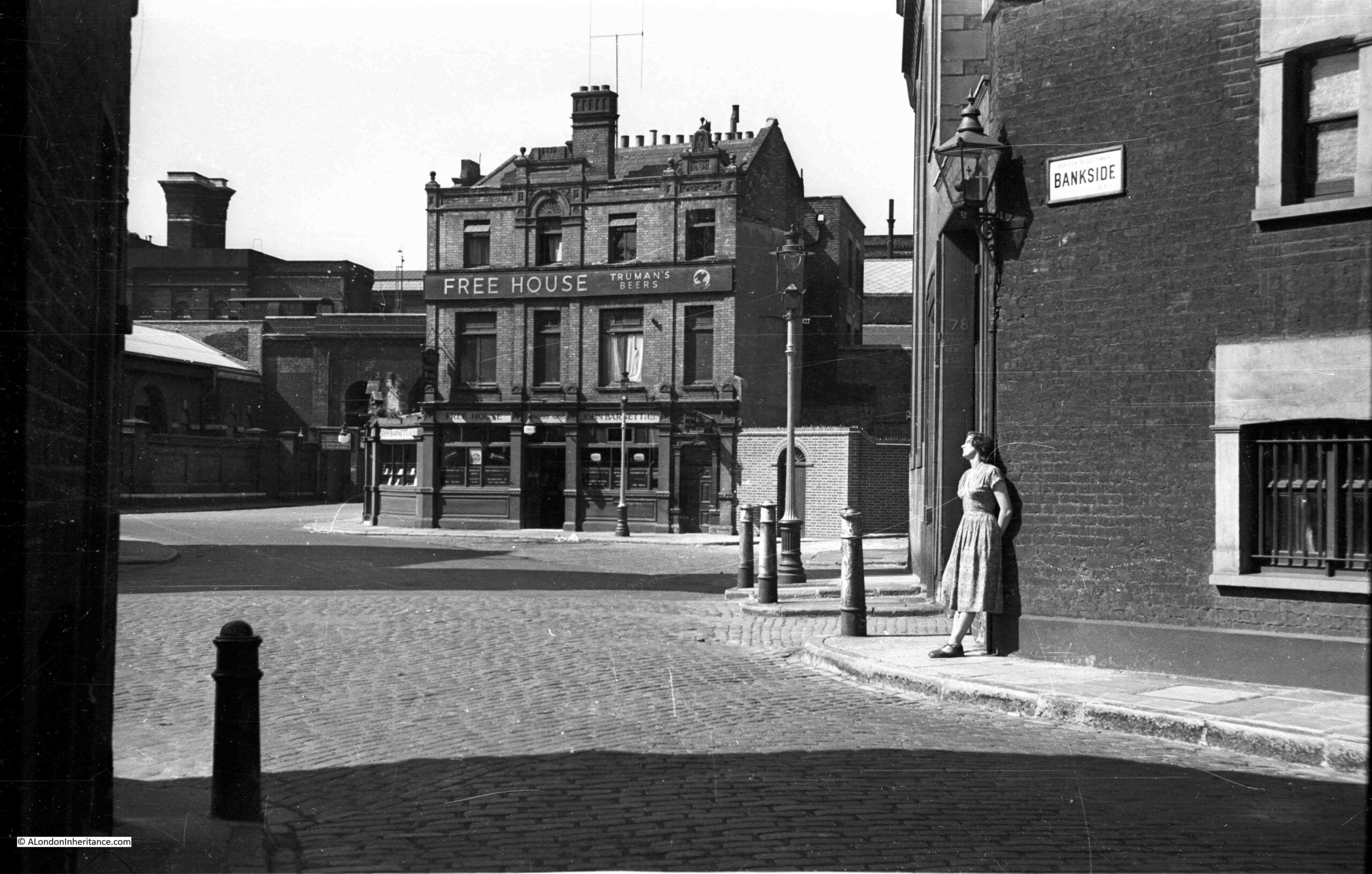

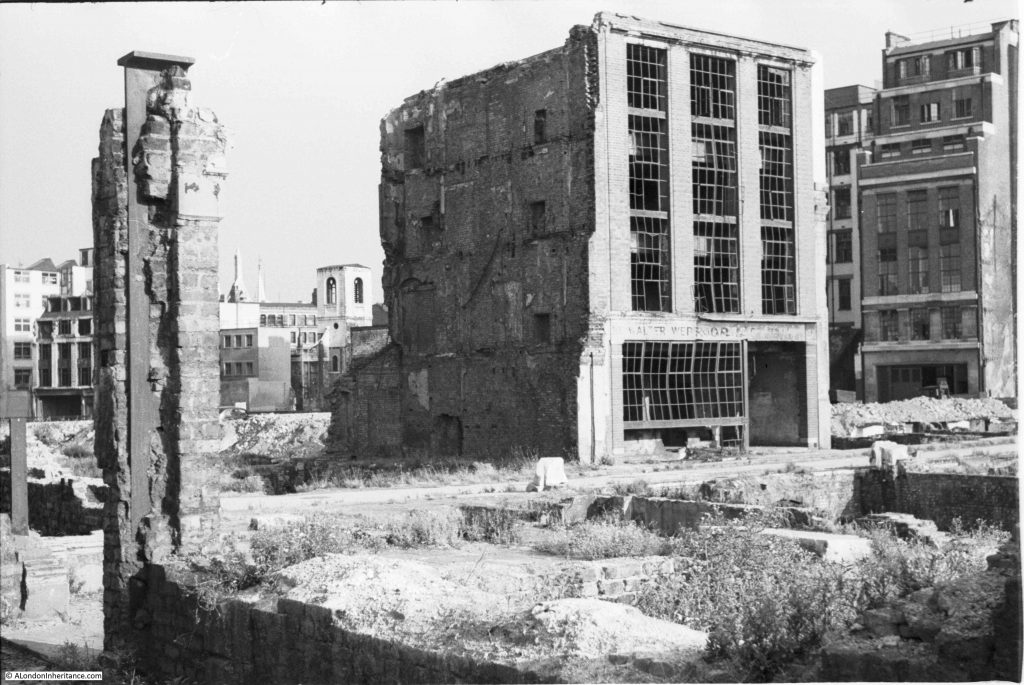

For this week’s post, I am back in the Barbican, looking for the location of one of my father’s photos of the area, taken soon after the war and before redevelopment had started.

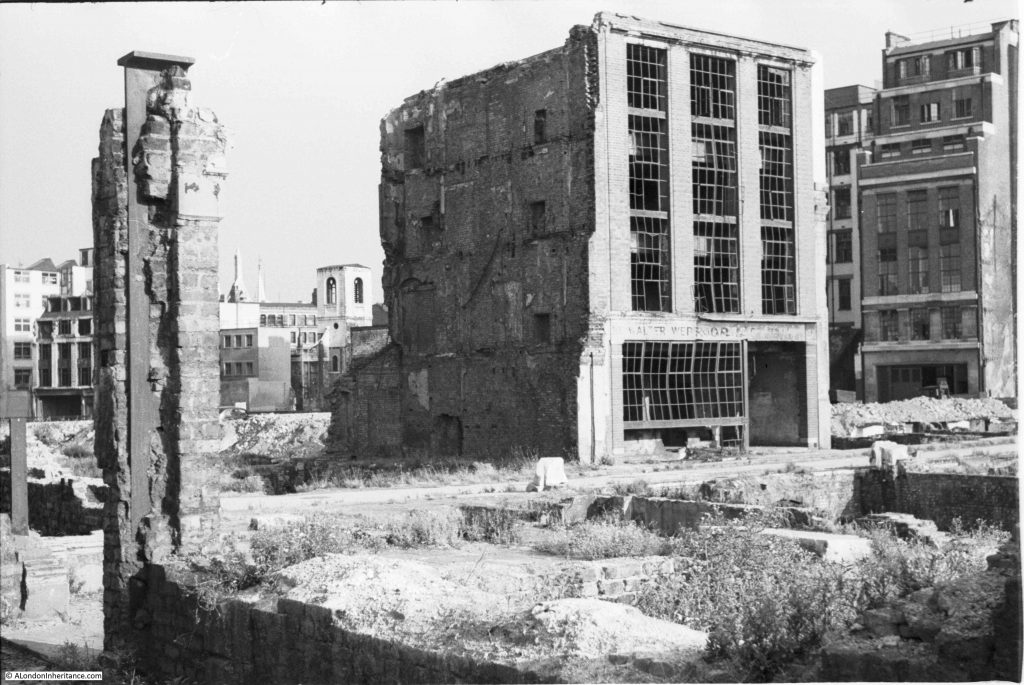

The photo shows a derelict building standing alone with surrounding buildings having been demolished down to their foundations. There appears to be a street running in front of the building.

Whilst the street has disappeared in the rebuilding between London Wall and the Barbican, I will hopefully bring the street back to life by discovering the history of Monkwell Street.

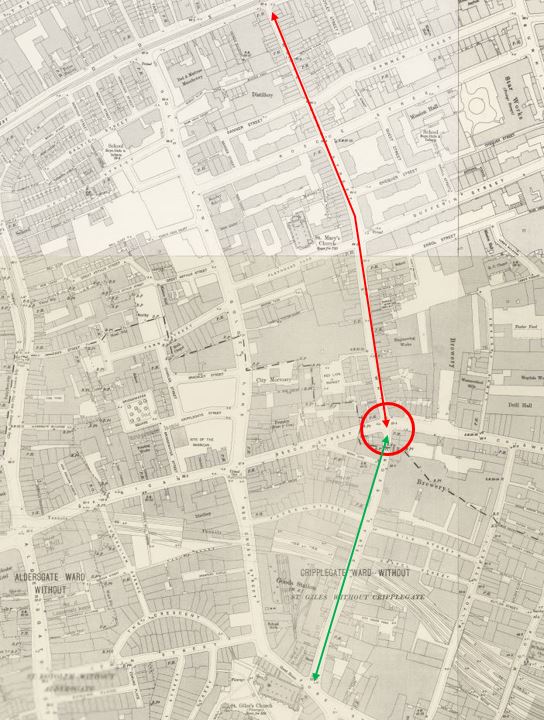

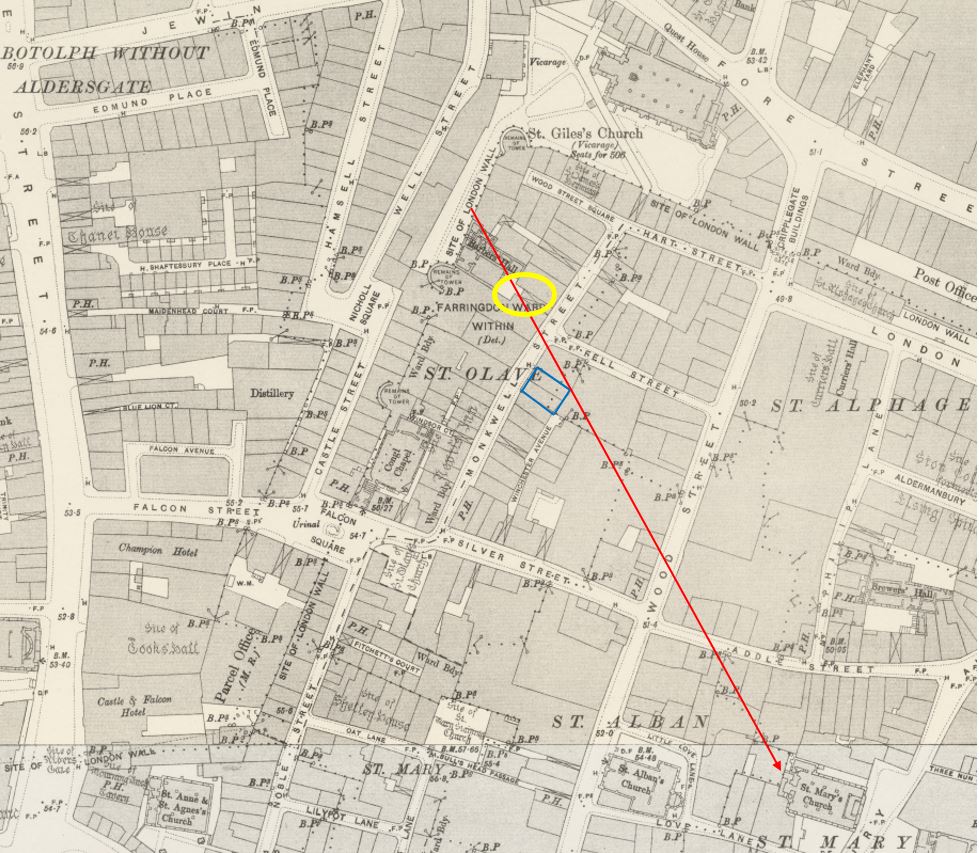

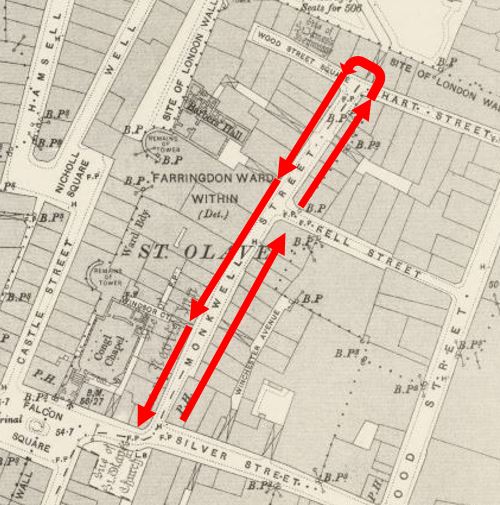

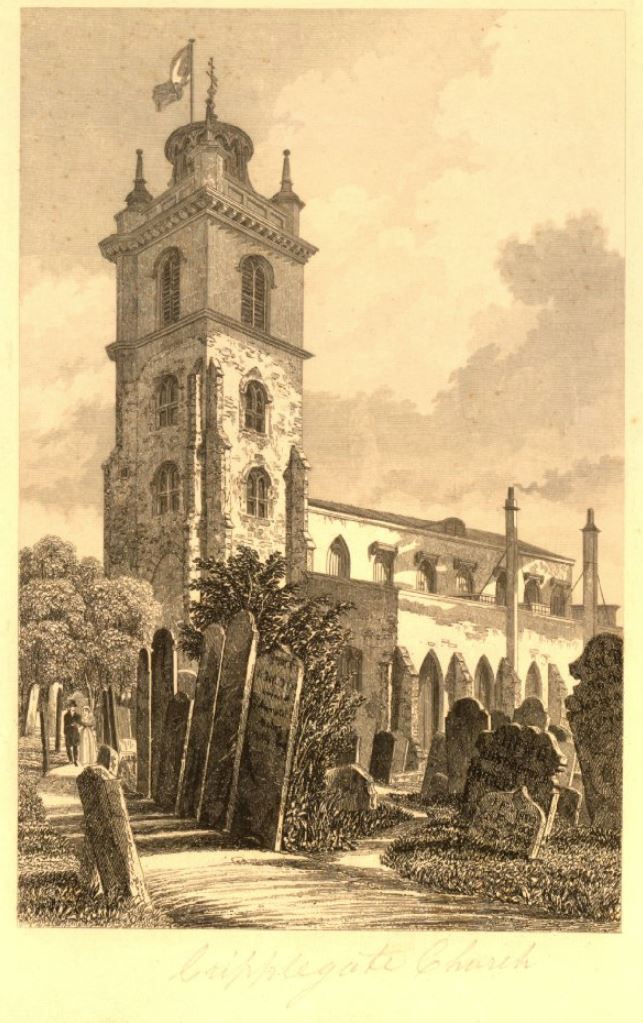

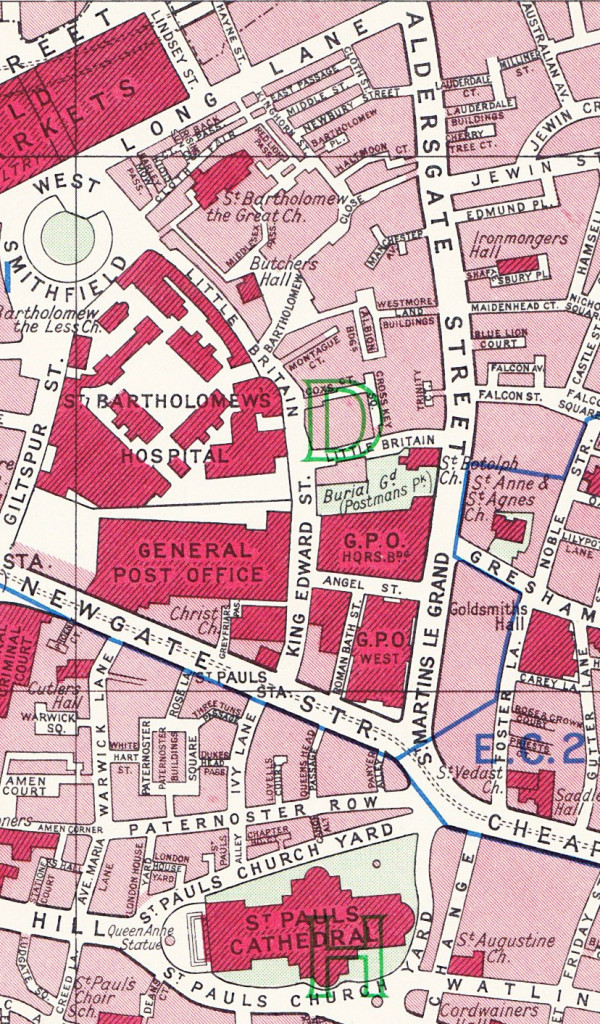

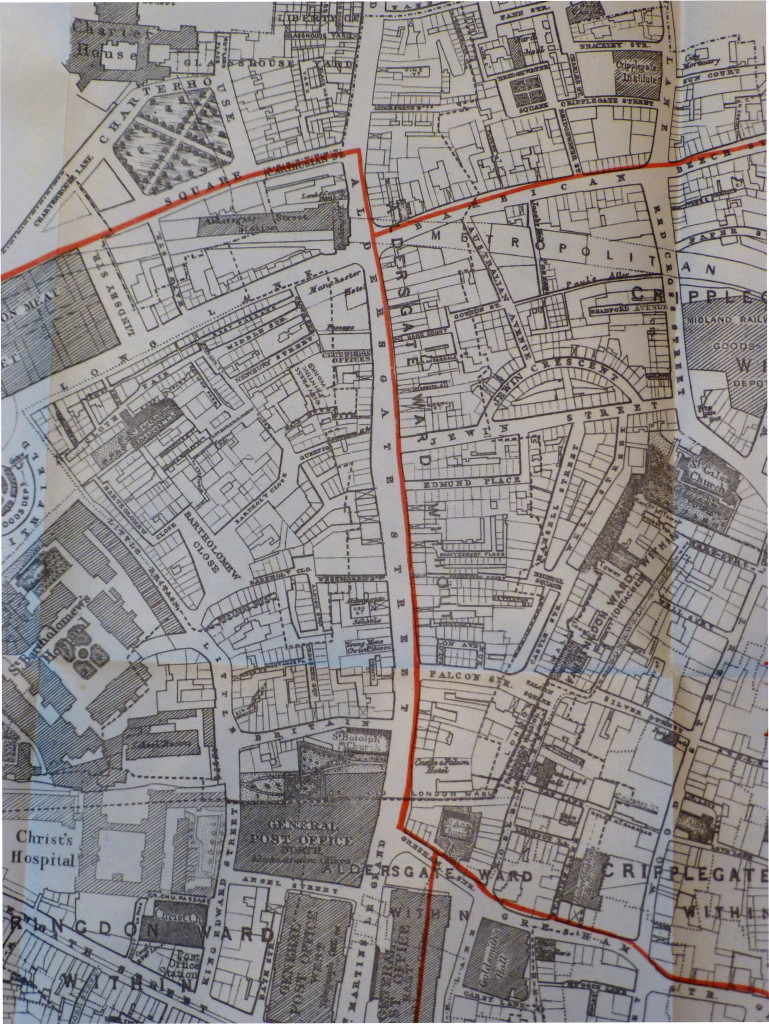

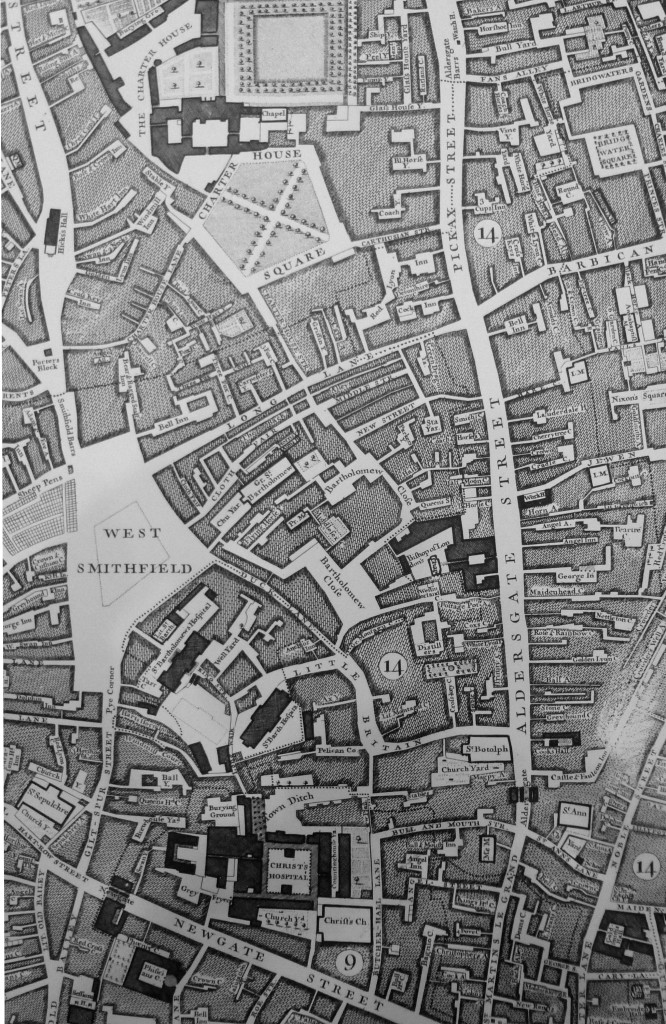

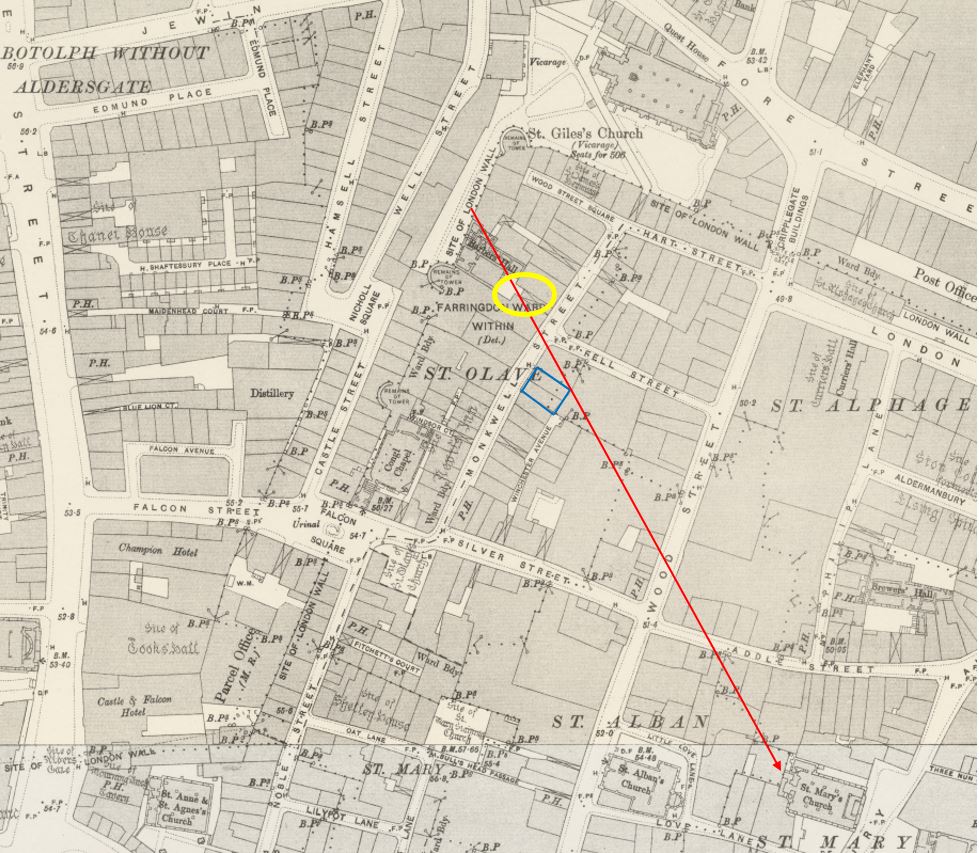

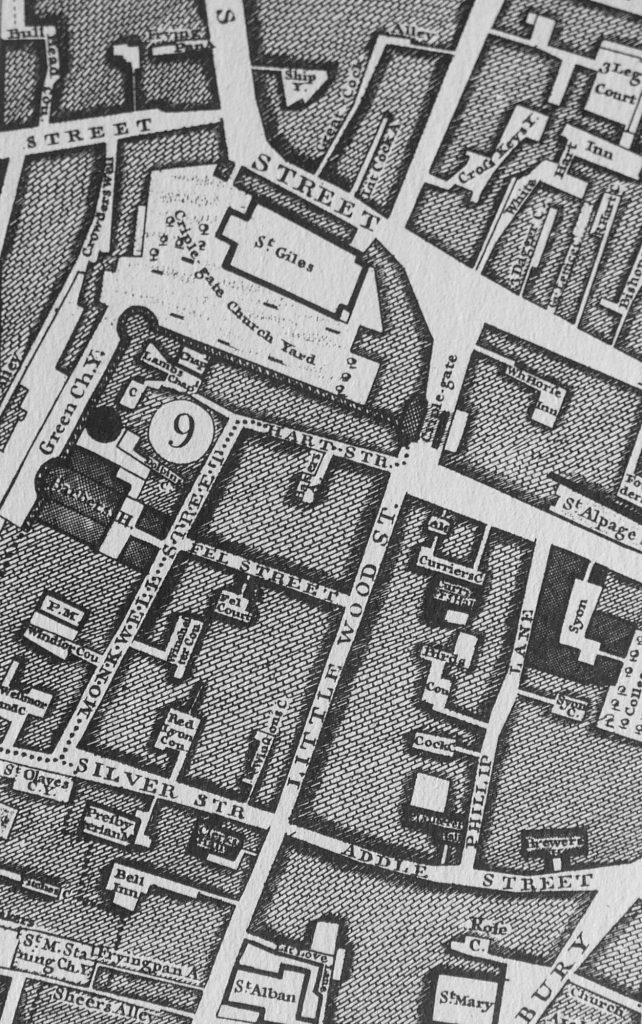

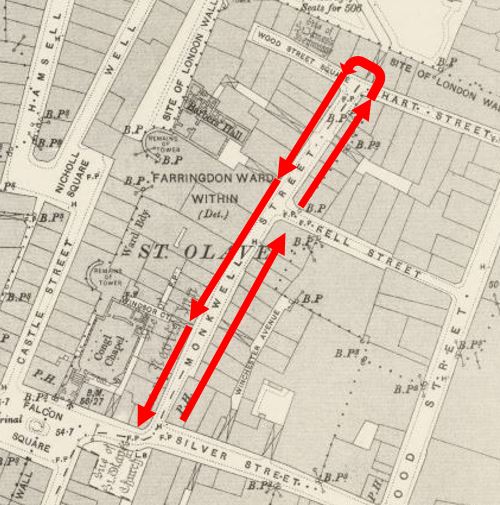

Where was the location of the photo and Monkwell Street? The 1894 Ordnance Survey map shows the street in the centre of the following extract (under the V of St Olave) running roughly north – south, terminating at the junction with Wood Street Square and Hart Street, just south of the church of St Giles Cripplegate which is almost the one fixed point we can find in the same area today (All OS maps are credit: ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’ .

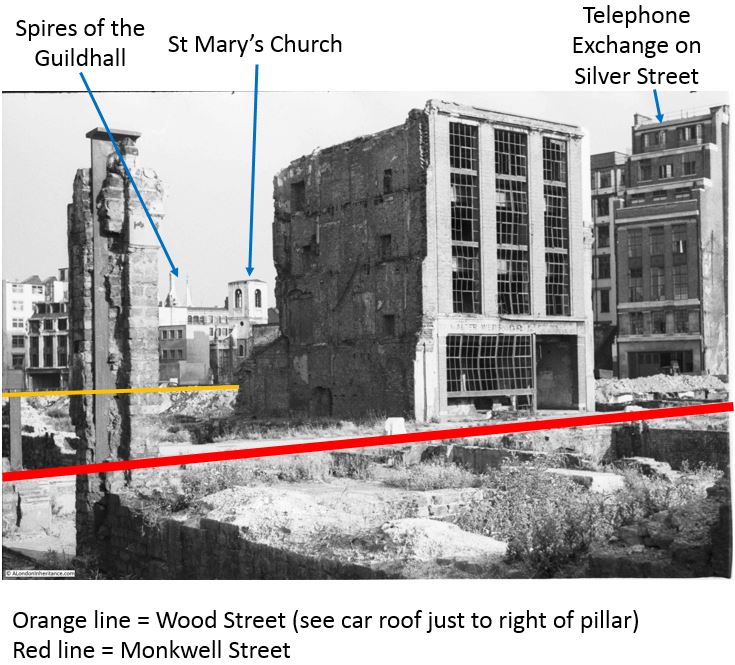

This photo was from a negative, so there were no written details of the location. I was able to find the location of the photo by using some of the features in the background, and the 1951 revision of the Ordnance Survey map.

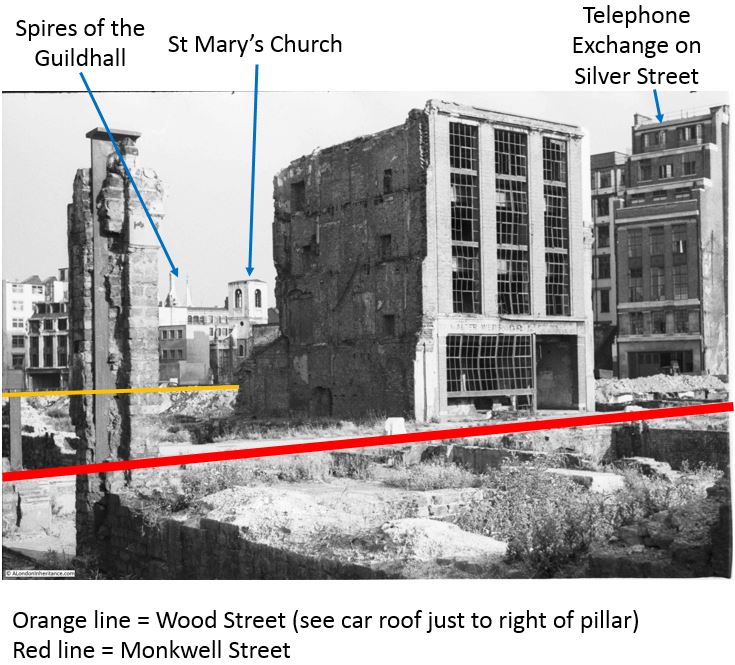

If you look at the original photo, just to the left of the derelict building is a church tower. This is the church of St Mary Aldermanbury, and the view to the church tower is just over the small brick extension to the ground floor at the rear of the building.

Drawing a line between the corner of the derelict building and the church tower on the 1951 map gives an idea of where the photo was taken.

I have marked up the photo with details of what is in the scene, including some of the background details such as the spires of the Guildhall, and the location of Wood Street and Monkwell Street.

There are a couple of additional photos of the same view, and using these I can narrow down the location for all photos to within the yellow oval in the following map, where there is a passageway from Monkwell Street to a small open space in front of the Barbers’ Hall.

The Worshipful Company of Barbers’ is one of the City’s livery companies and had an address on Monkwell Street, although was set back from the street and reach through a passageway.

In the following photo of the same view, but from a slightly different position, there is a pavement between the remains of walls in the foreground. This is the passageway leading from Monkwell Street to the Barbers’ Hall.

And in the following photo which is slightly further back from the previous two, and looking slightly to the right, there is the remains of a wall, with a door. This is where the passageway opened out to the small open space in front of the Barbers’ Hall. The door must have been to whatever was at the rear of the building on the southern side of the passageway.

The majority of the damage done to Monkwell Street was during the night of the 29th December 1940 when the area north of St Paul’s covering the area now occupied by London Wall and the Barbican and Golden Lane estates were devastated by fire and explosives.

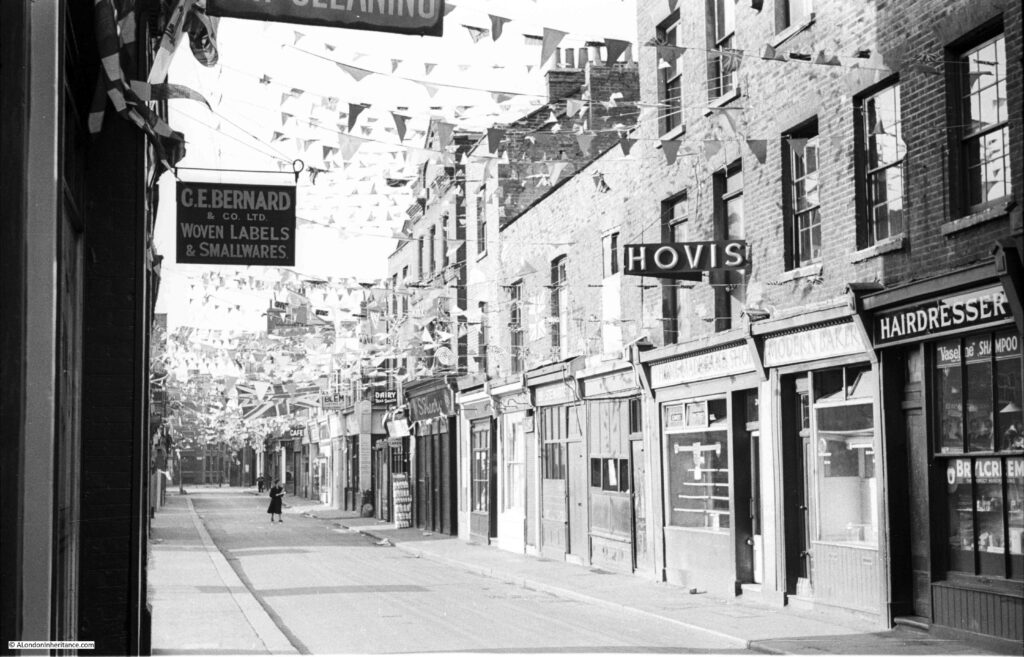

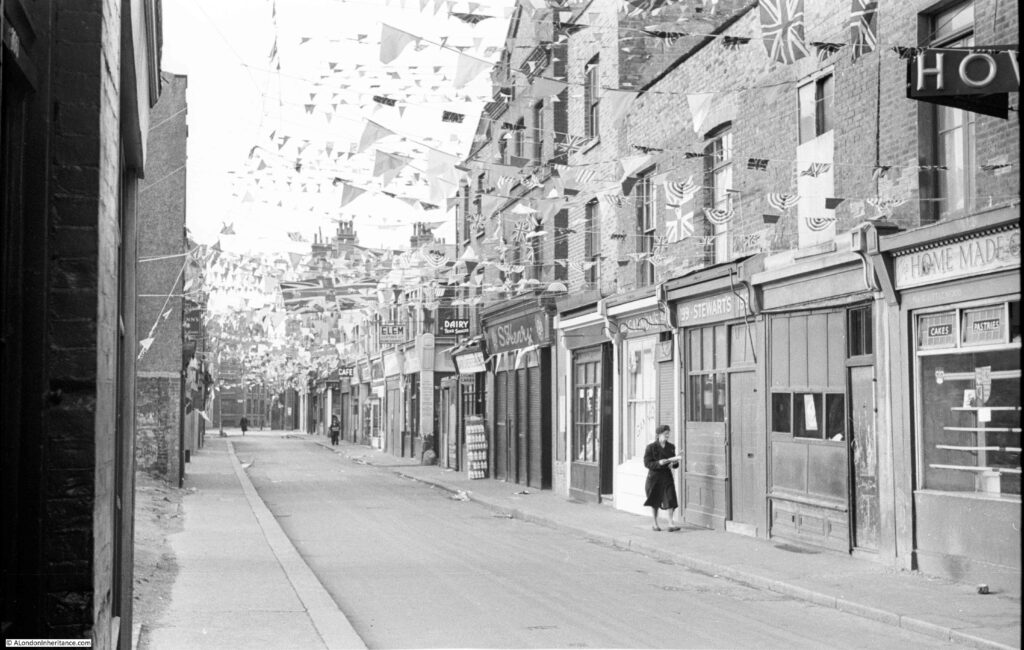

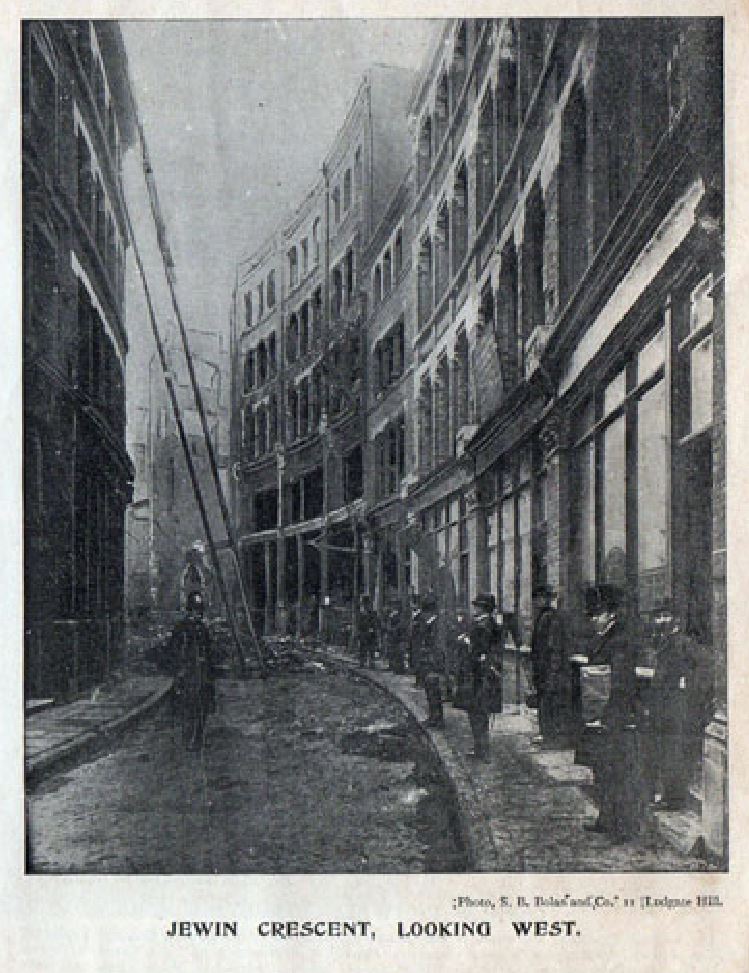

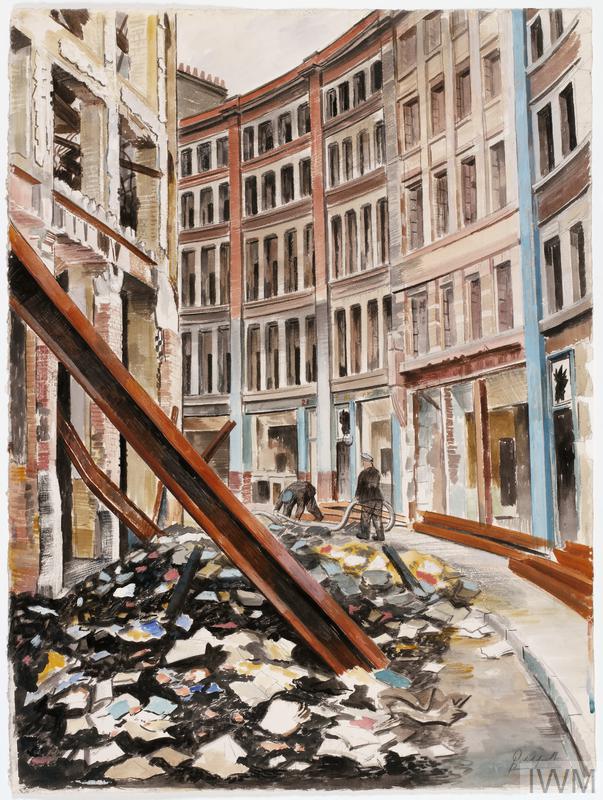

The following photo from the London Metropolitan Archive, Collage collection shows Monkwell Street after the raids. The view is looking north with the church of St Giles Cripplegate visible at the end of the street.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: M0019302CL

To the left of the photo is an arched passageway leading off from the street. I suspect this was the passageway leading to the Barbers’ Hall. By the time my father took the photos, the area had been cleared down to foundation level to remove the danger of collapsing walls and falling masonry. I do not know why the single building in my father’s photos was left as it does look badly damaged.

Is there anything left of Monkwell Street today? Apart from an element of the name, the answer is no.

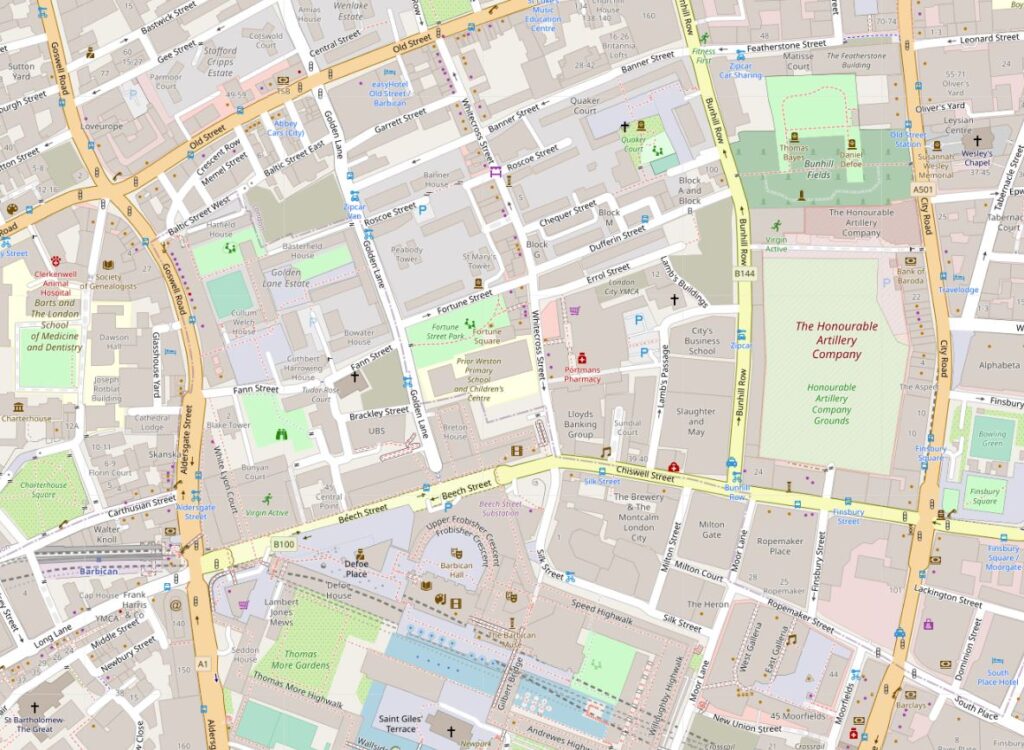

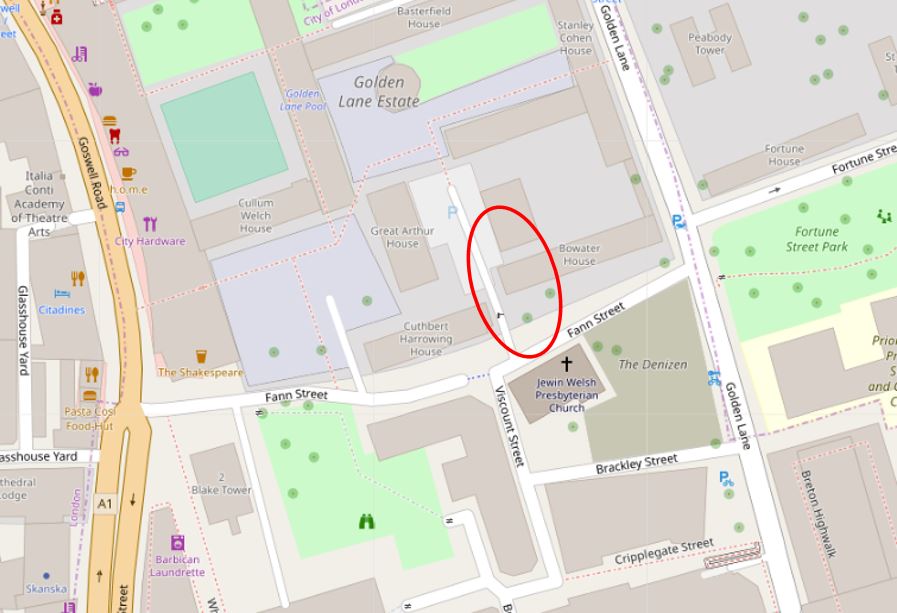

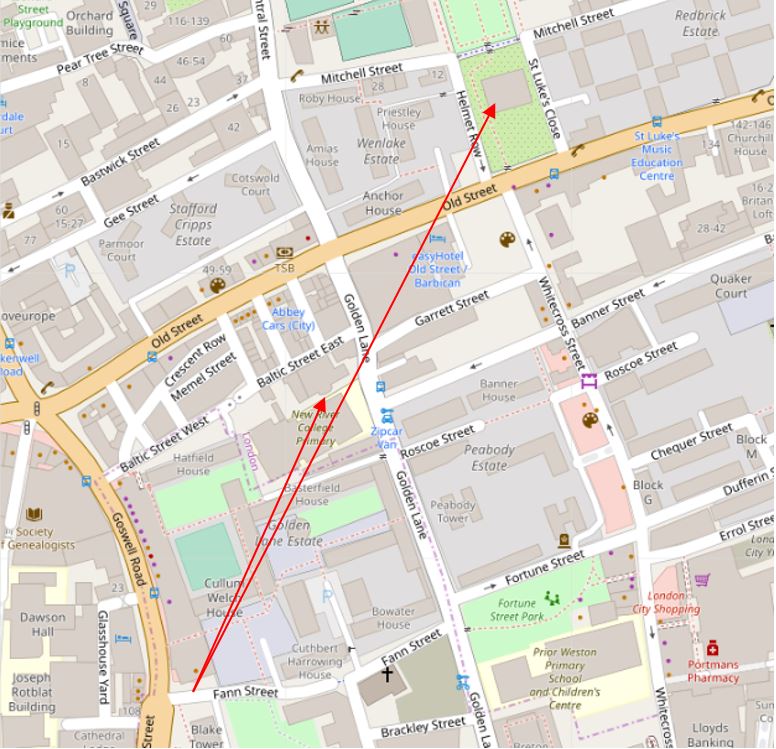

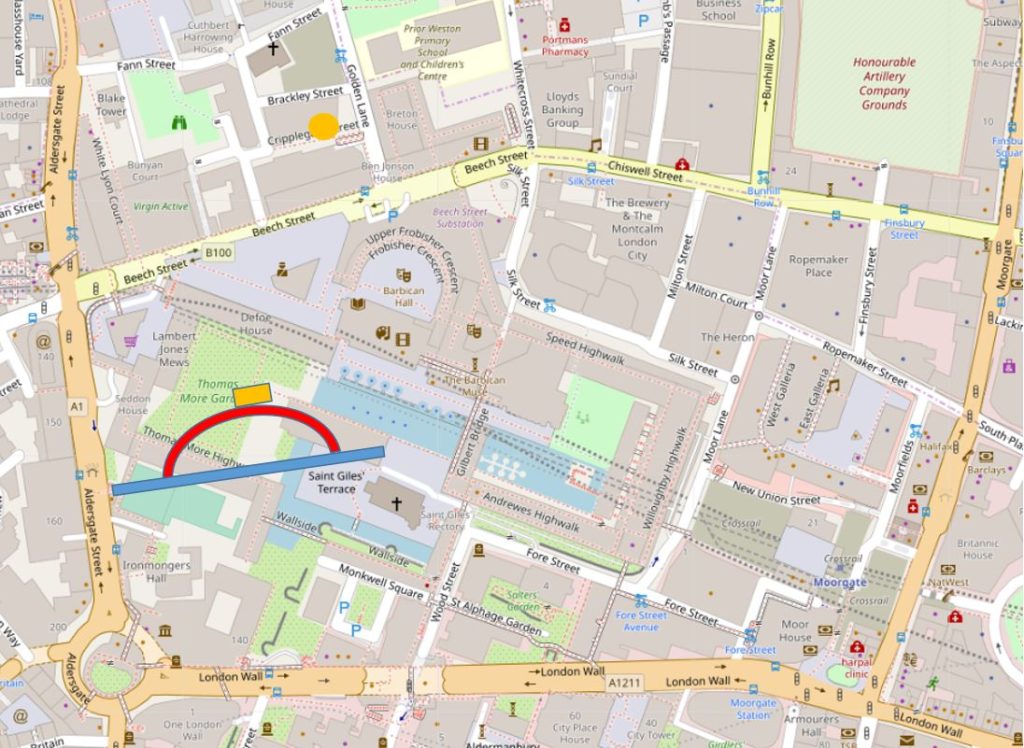

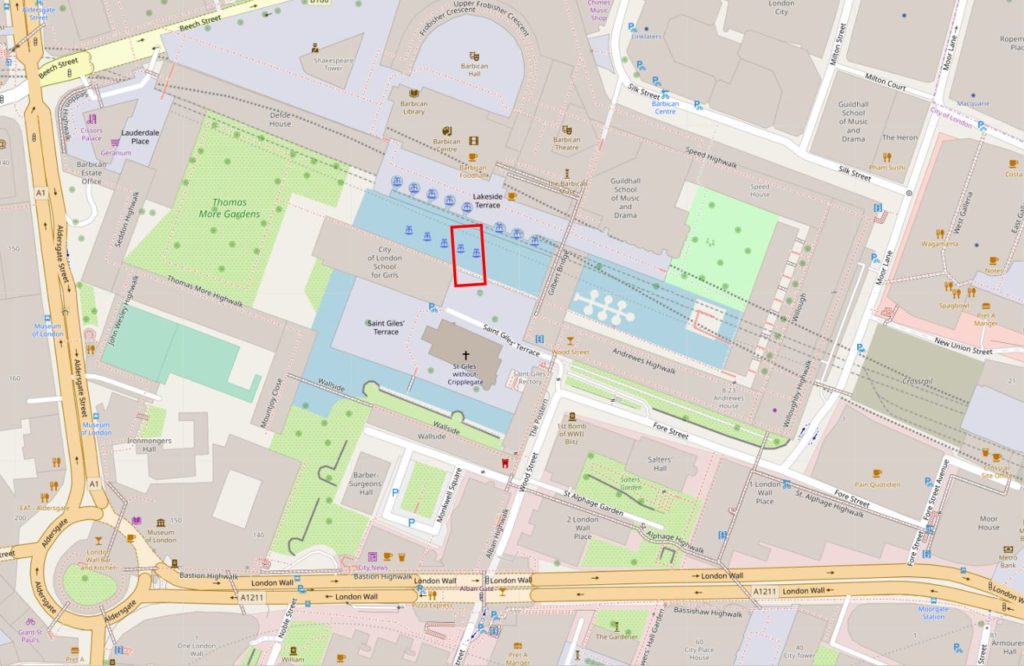

I have marked the approximate location of Monkwell Street on today’s map in the extract shown below (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

The street ran up from what is now London Wall (previously Silver Street and Falcon Square), to just south of St Giles, where a line of buildings separated the end of Monkwell Street from St Giles churchyard.

On a wet day in October of last year I was in the area of the Barbican and went to have a look at the area once occupied by Monkwell Street. These are poor photos due to the weather, I had intended to return this spring to photograph the area again in better weather, but the Barbican is a bit too far for an exercise walk.

There are no physical remains of Monkwell Street. The name does remain in a route that leads off from Wood Street, the name Monkwell Square applies to this route, and the square in front of Barbers’ Hall. This is not a general access road, it has a barrier across so only accessible for residents of the buildings on the right, the hall and the offices on the left.

The above entrance street to Monkwell Square runs parallel, but slightly to the south of Hart Street on the 1894 OS map.

The following photo is looking across Monkwell Square to the Barbners’ Hall – the light brick building directly across the square. Monkwell Street ran left to right, almost directly in front of Barbers’ Hall in its current location.

The Barbers’ Company is one of the old Companies of the City, dating back to the early 14th century. The company was incorporated by charter in 1461.

For many years there was friction between Barbers and Surgeons. This combination of trades came from the employment of barbers in medieval monasteries for the purpose of blood letting, and as Barbers made use of sharp instruments and their gradual development of basic surgery. A Guild of Surgeons was based in London in the early 15th century, competing with the Barbers’ Company. In 1462 Edward IV granted the Barbers’ their first Royal Charter to regulate the practice of surgery in London.

In 1540 the roles of barbers and surgeons in London were defined by an Act of Parliament. The act also combined regulation of the two trades within the combined Company of Barbers and Surgeons. The act ensured that Barbers could not perform any surgery and Surgeons could not cut hair or shave another, although both trades could continue to pull teeth.

As the profession of Surgery developed and grew in status, the association of Barbers and Surgeons within the same Company was uneasy and an Act of Parliament in 1745 constituted surgeons as a separate body, one that eventually became the Royal College of Surgeons.

From 1919, links between the Barbers’ Company and the Royal College of Surgeons were established and today surgeons are also members of the Barbers’ Company.

The following photo shows the hall of the Barbers’ Company facing onto Monkwell Square.

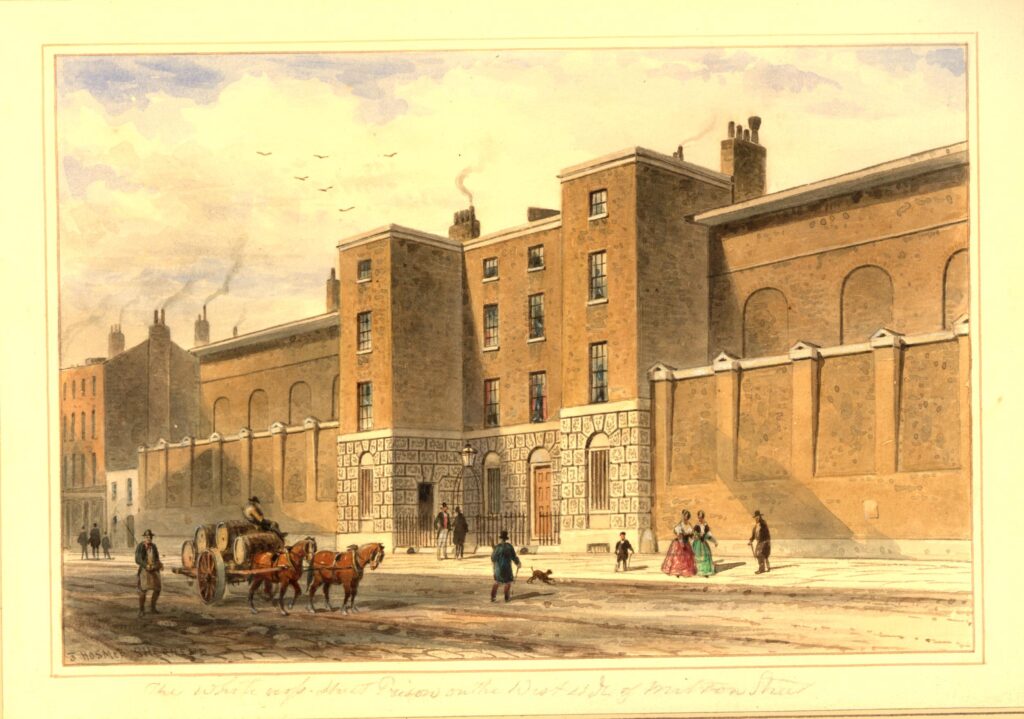

In the above photo, Monkwell Street ran left to right almost directly in front of the hall. Originally, and as shown in the OS maps, the hall was set back further from Monkwell Street and reached through the alley. The hall was destroyed during wartime bombing and was rebuilt 30 feet to the east, as the earlier hall had included the medieval bastion in the western side of the building, and the rebuild required the bastion to be free standing.

This move of the hall to the east, therefore built over much of what was the alley, and took the front of the hall almost up to where Monkwell Street once ran.

To take the photos, my father was therefore standing somewhere just inside the Barbers’ Hall.

Walking towards London Wall and there is an office block facing onto the southern side of Monkwell Square. It is hard to be precise, but the following photo is looking roughly along the western edge of where Monkwell Street once ran, with the Barbers’ Hall on the left, the Wallside terrace of the Barbican development at the far end, occupying the space once occupied by Hart Street and Wood Street Square.

Much of the space to the west of Monkwell Street, apart from the Barbers’ Hall, is now open space, providing grass and a walking route along the old route of the Roman wall, and the medieval bastions.

In the following photo, London Wall is on the right, Barbers’ Hall on the left, and Monkwell Street ran left to right, in front of the brick building directly opposite.

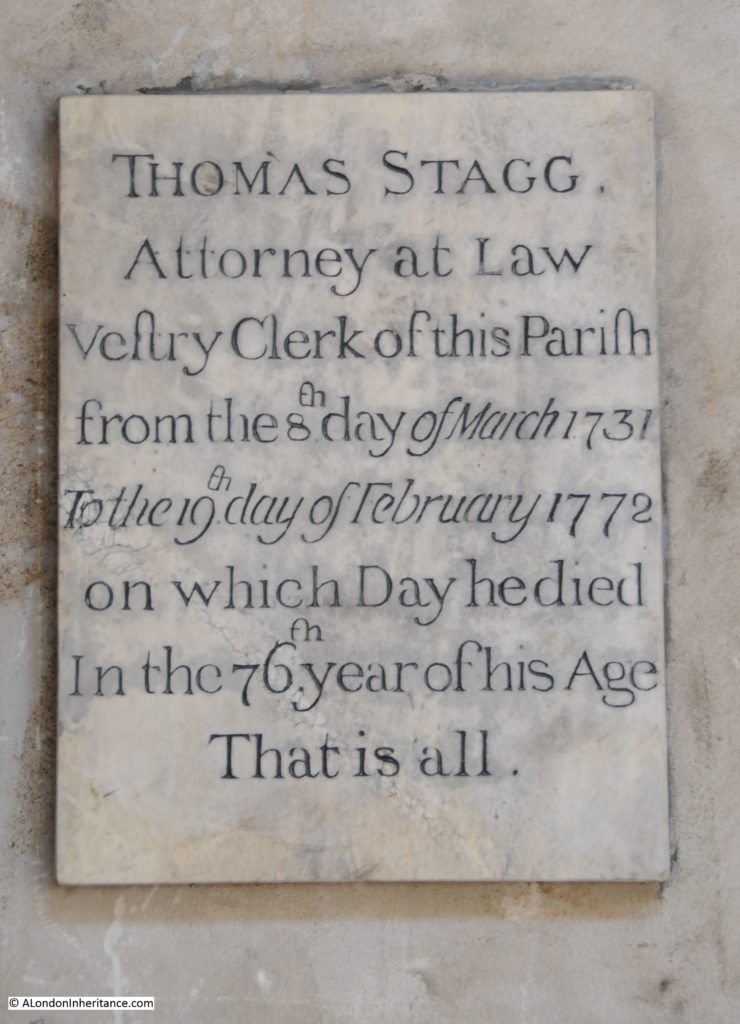

Monkwell Street was a very old street. In ‘A Dictionary of London’ (1918), Henry A. Harben writes the following regarding the name and age of the street:

“First mention: ‘Mukewellestrate’ in the 12th century. Other forms ‘Mogwellestrate’ 1287, ‘Mugwellestrate’ 1306, Mugglestreet’ 1596, ‘Munkes Well Streete’, ‘Mongwell Street’ (1666), ‘Mugwell Street’ (1677), ‘Monkwel Street’ or ‘Mugwel Street’ (1708).

Stow says the street was so named of a well at the north end, which belonged to the Abbot of Garendon, whose house or Cell was called ‘St James in the Wall’, of which the monks were the chaplains.

Riley says that this derivation is purely imaginary, and suggests that the earliest forms were Mogwell or Mugwell Street. This is, however, an error, for though the street was called by these names interchangeably from the 13th to the 18th centuries, the earliest form is, as shown above, ‘Mukwellestrate’ and this may easily have been a contraction of ‘Munkwell’ the ‘n’ being omitted.

On the other hand, it seems more probable that the name is derived from the family name ‘Muchewella’, ‘Algarus de Muchewella’ being mentioned in a deed of the early 12th century. The family may have been named from the well. There seems to have been a well in existence under the crypt of Lamb’s Chapel in this street.”

It is next to impossible to be absolutely certain as to the source of a street name, however I have found Harben to be one of the more well researched and accurate sources of information regarding the naming and history of London’s streets.

What is clear is that Monkwell Street was a very old street, dating back to at least the 12th century, but lost during the redevelopment of the area in the 20th century.

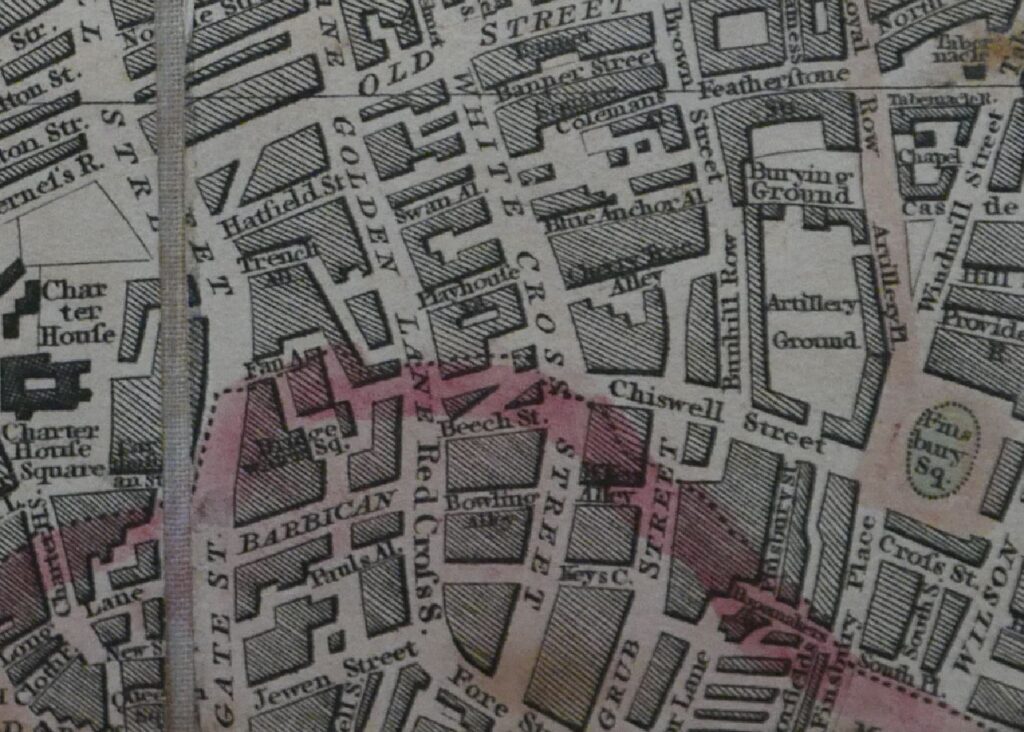

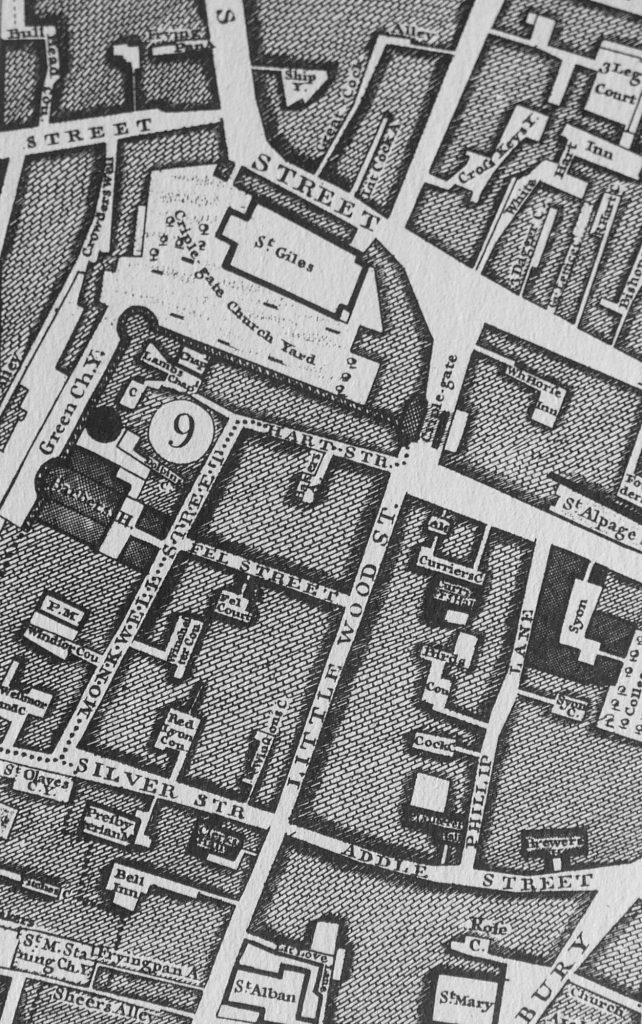

In 1746, Rocque shows Monkwell Street looking much as it would do 150 years later in the 1894 Ordnance Survey maps, running between Silver and Hart Streets, with Fell Street (although with a single L) on the right and the courts on the left.

The last sentence of Harben’s account of the street mentions a Lamb’s Chapel (also Lambe) in Monkwell Street. The location of this can be seen in the above map where at the top left of Monkwell Street is marked Lamb’s Chapel, above the large number 9.

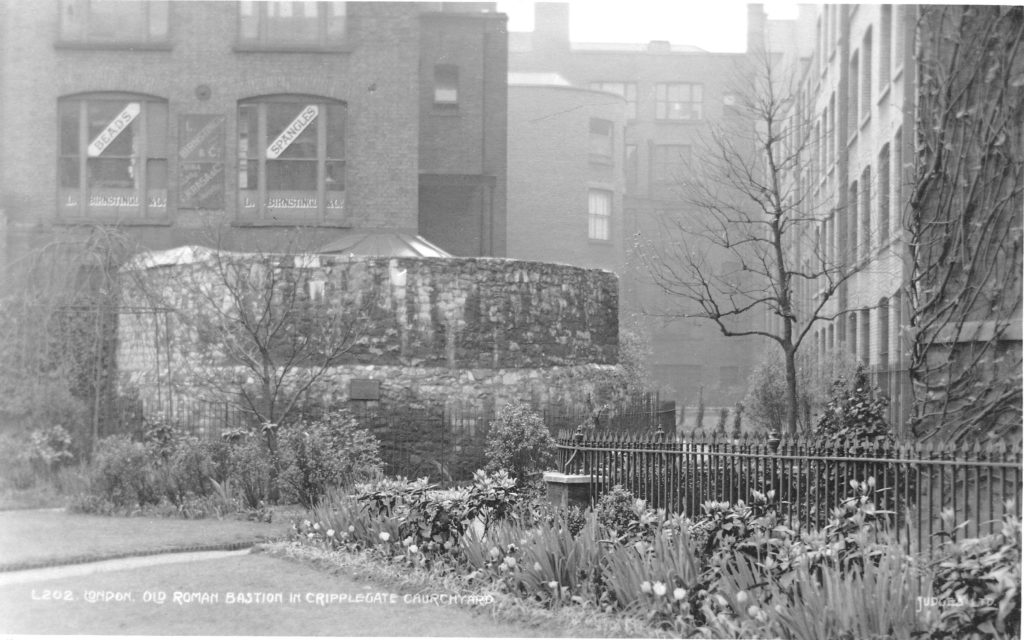

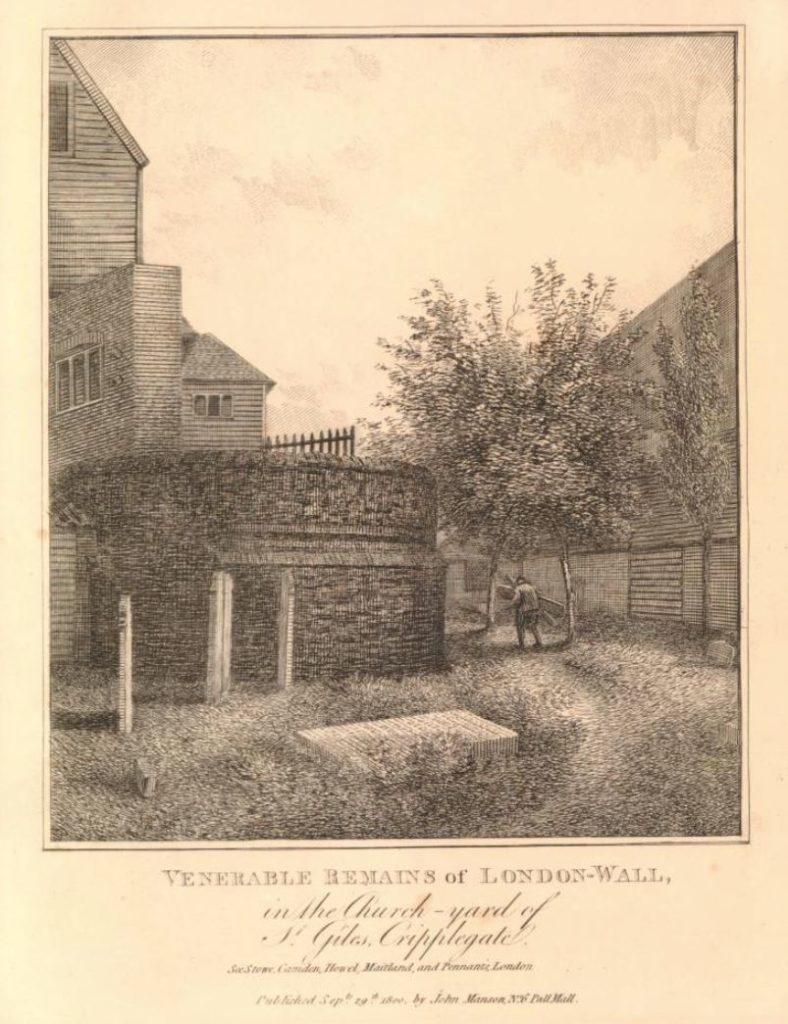

In the following photo taken from one of the Barbican walkways, the bastion seen to the upper left of the number 9 in the 1746 map is at the far end of the grass space. In the map, the chapel is shown up against the old wall, to the right of the bastion. Although a stretch of the wall has since been lost, the chapel was up against the wall, roughly to the left of where the footpath crosses the water.

A corespondent to the Gentleman’s magazine describes the chapel in the 1783 edition:

“Lamb’s Chapel is a place perhaps not one in a thousand of your numerous readers hath ever visited. It is situated in an obscure court, to which it gives its name, at the north west corner of London Wall. It was founded in the reign of Edward I, and dedicated to St. James, when, it was distinguished from other places of religious worship of the same name by the denomination of St. James chapel, or hermitage, on the wall, from it being erected at or near the city wall in Monkwell Street.

At the dissolution of the religious houses, King Henry VIII granted this chapel to William Lamb, a rich clothworker, who bequeathed it, with other appurtenances, to the company of which he was a member, and from him it received its present name.

In this chapel is a fine old bust of the founder in his livery-gown, placed here in 1612, with a purse in one hand and gloves in the other. here are also four very delicate paintings on glass of St Peter, St Matthew, St Matthias and St James the Apostle.

It is in length from east to west thirty-nine feet and in breadth from north to south fifteen. In it are a pulpit, a font, a communion-table, with the portrait of Moses holding the two tablets, and a half length carving of the founder. The chapel is furnished with seats, benches and other accommodations for the master, wardens, and liverymen of the clothworkers company, and also with seats for the almsmen and women. There are also a few gravestones although some the brass plates are taken away, but on others they remain. The only inscriptions now legible are, one to Henry and Elizabeth Weldon of Swinscombe in kent, 1595 and another to Catherine Hird, daughter of Nicholas Best of Grays Inn, 1609″.

Lamb was a member of the Clothworkers’ Company and became their Master in 1569. He died in 1580 at the age of 85 and bequeathed the chapel to the Clothworkers’ in his will

The Clothworkers’ decided to close the chapel and almshouses in 1820, and they were both rebuilt on land the Clothworkers’ owned in Islington. The new church was dedicated to St James’ with St Peter, thereby reinstating the original pre-dissolution dedication of the chapel of St James on the Wall.

The 1612 bust of Lamb mentioned in the Gentleman’s magazine extract was moved to St. James, islington, where it can still be seen.

The crypt of the old chapel was later moved by the Clothworkers’ Company to All Hallows Staining, where it remains to this day.

The almsmen and women mentioned in the above text were from some Clothworkers’ Almshouses built adjacent to Lamb’s Chapel. The crypt of the chapel was still in existence in 1859 when it was part of the first visit to the City by members of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society.

The crypt of Lamb’s Chapel in 1859:

As well as the Clothworkers’ the Salters’ Company had a terrace of Almshouses in Monkwell Street for four hundred years. They were located along the east side of the street between Hart Street and Fell Street.

The original almshouses were built in 1578 by Ambrose Nicholas, Lord Mayor of the City. The almshouses accommodated twelve women. The original almshouses were destroyed during the 1666 Great Fire, after which the Salters’ Company rebuilt the almshouses, and it is these buildings which appear in the following drawing of the Salters’ Almshouses in 1818:

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: q8051250

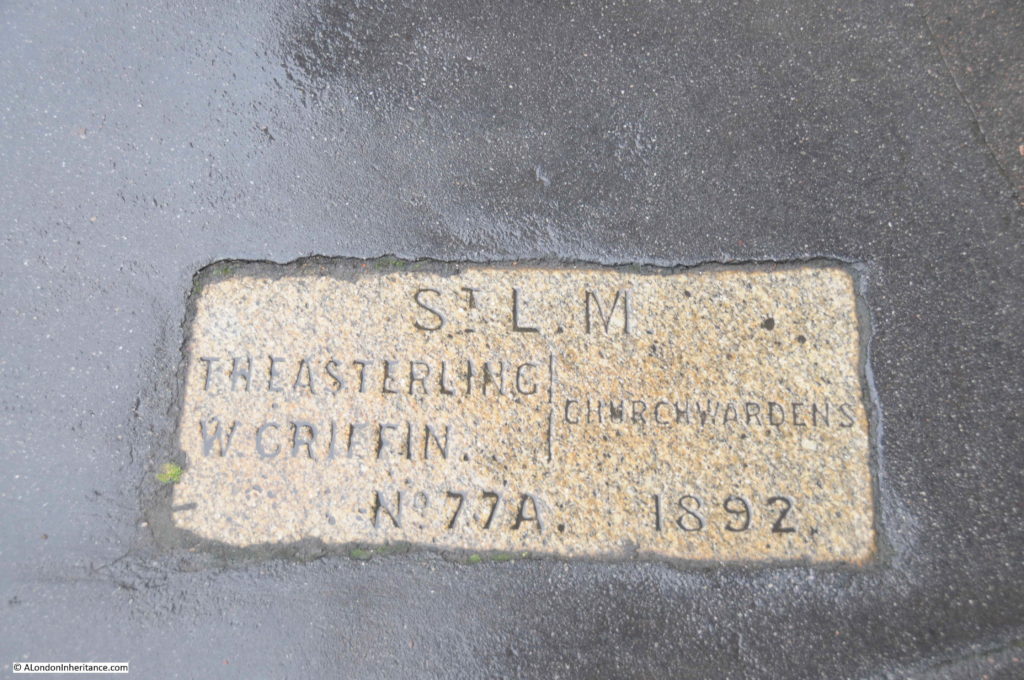

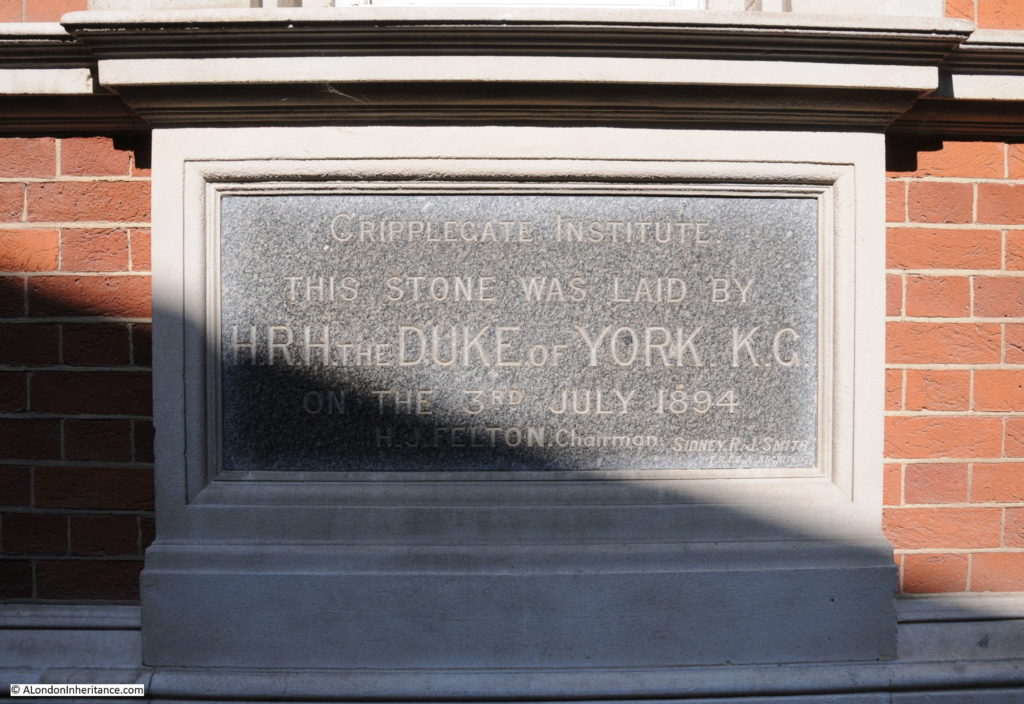

The plaque details the founding of the almshouses and was located above the central door of the terrace.

The almshouses survived to 1864, by when they had become rather dilapidated. They were demolished after the move of the residents to new Almshouses in Watford. A report in the Illustrated London News provides the reason for the remove, one which sounds very similar to today, where the value of London land is often the driver for a change to more profitable use: “The rebuilding of the almshouses of the civic companies in the environs of the metropolis instead of the densely crowded City, as occasion requires, is a sanitary change much to be commended. It is true that we miss many a quaint old building in a quiet City nook and on the margin of the great town; but the value of property in these localities has increased to such an extent as to render the removal profitable to the funds of the company, besides adding to the lives and comforts of the poor almspeople”

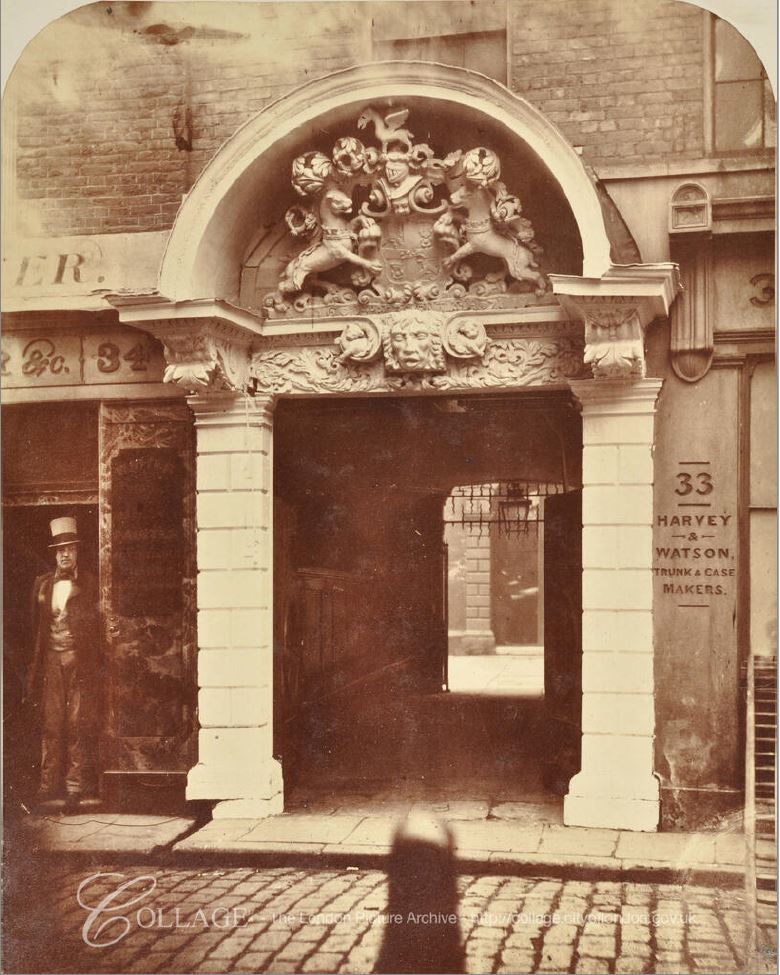

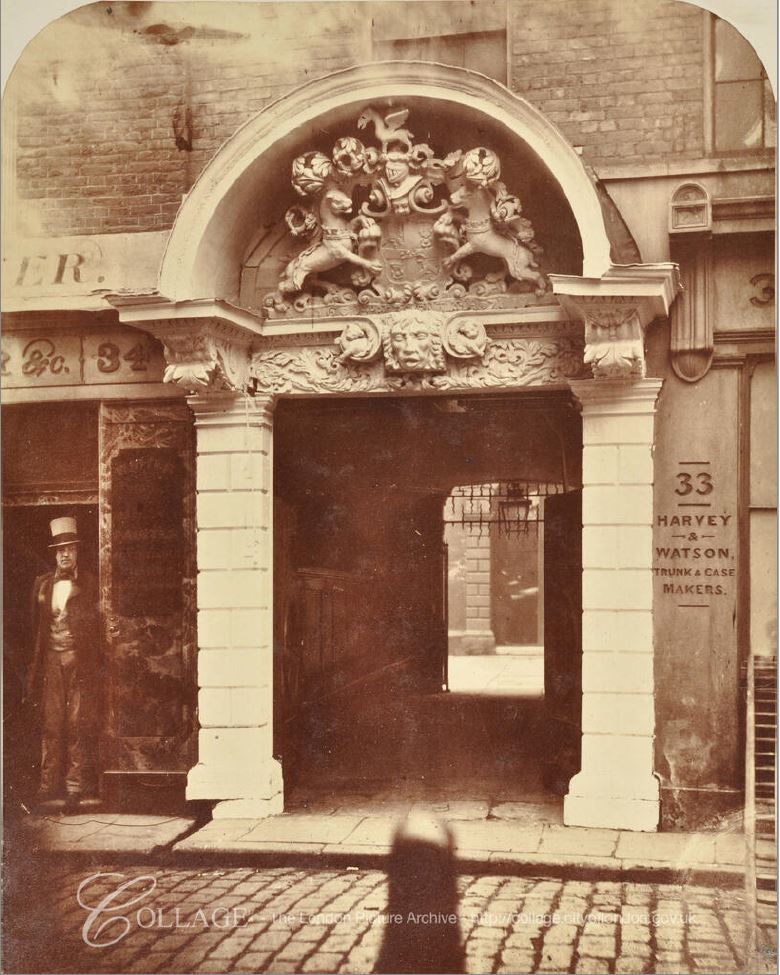

As well as the drawing of the almshouses, I found a couple of photos of the passageway that led from Monkwell Street to the Barbers’ Hall.

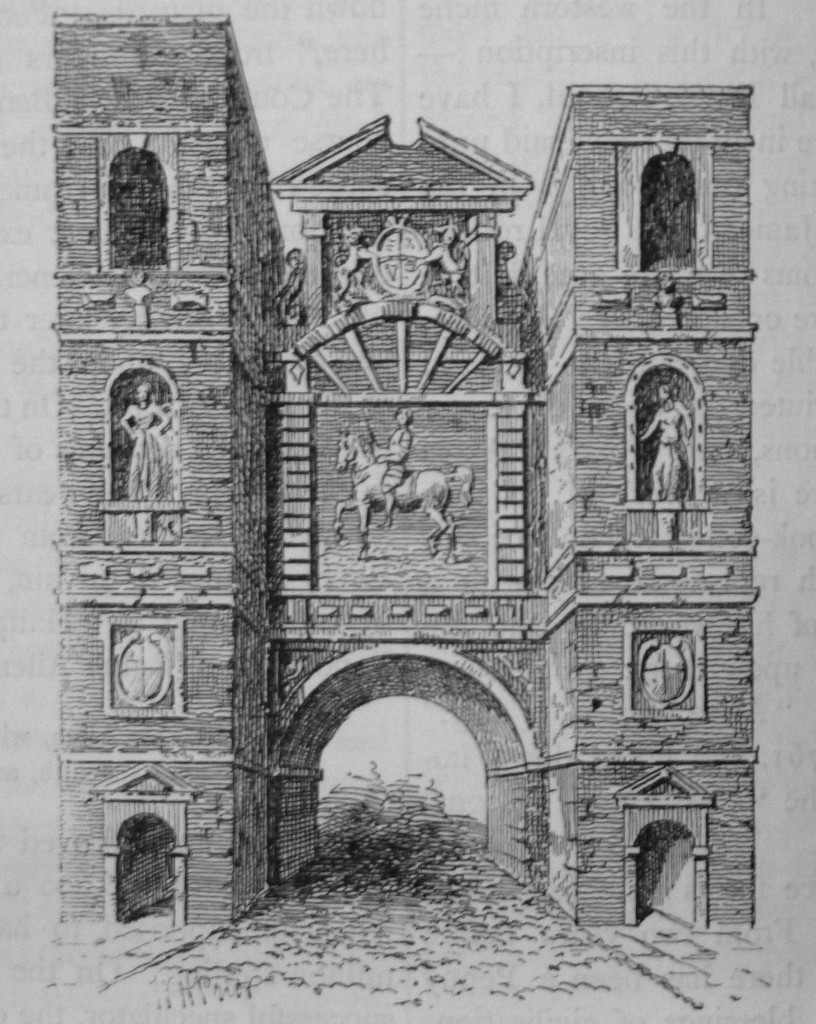

The first photo dates from 1863 and shows the entrance to the passageway, with the courtyard and Barbers’ Hall part visible at the end of the alley. At the time the entrance was described as “Inigo Jones’s picturesque entrance”. It was around this courtyard that my father took the photos of a devastated landscape.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: m0010600cl

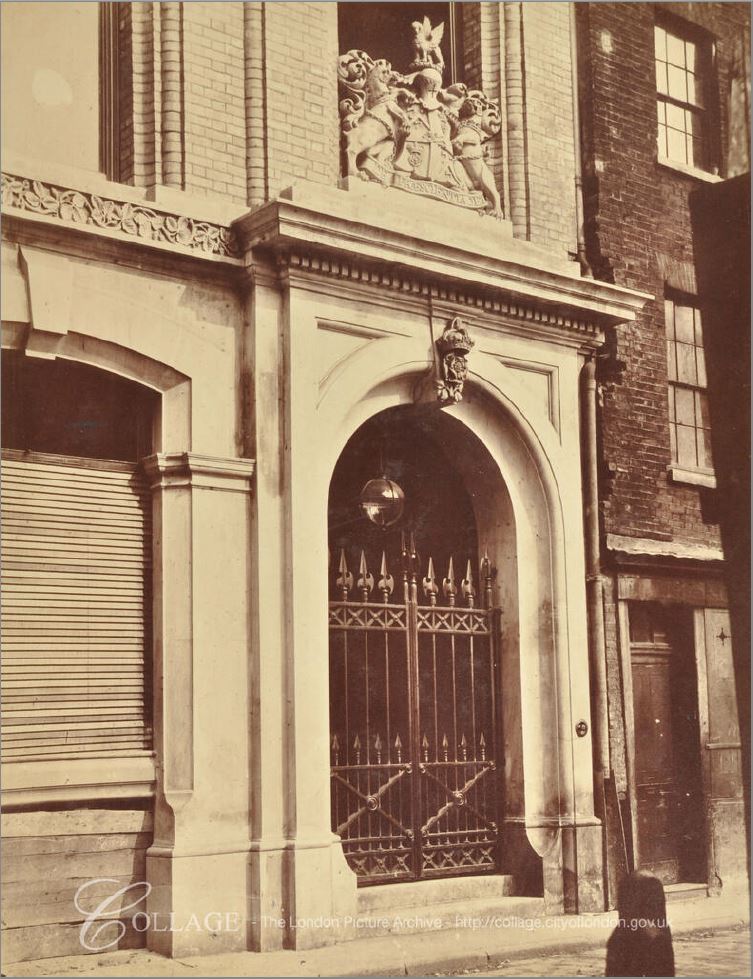

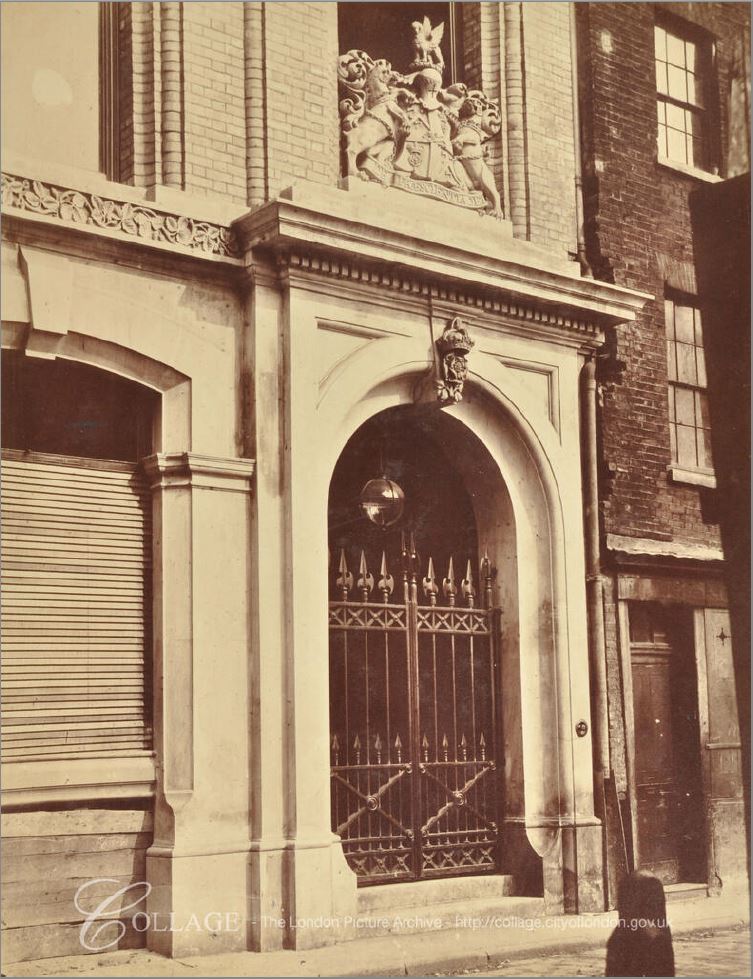

In 1863 / 1864 after the above photo was taken, it appears that the building with the passageway at the lower right was demolished and a new building and passageway constructed. The following photo from 1864 shows the new entrance to the Barbers’ Hall.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: m0010599cl

I like to really understand who lived and worked in London’s streets. the architecture can only tell you so much. It is the details of those who lived and worked in the street that can really bring the street to life.

Monkwell Street had long between an industrial / commercial street. Census reports list very few people actually living in the street, with the buildings instead being occupied by manufacturers, agents and warehouses. The move of the almshouses consolidated the street as one long run of industrial / commercial premises, and we can get a good view of the trades working in Monkwell Street by looking at the directories of the time.

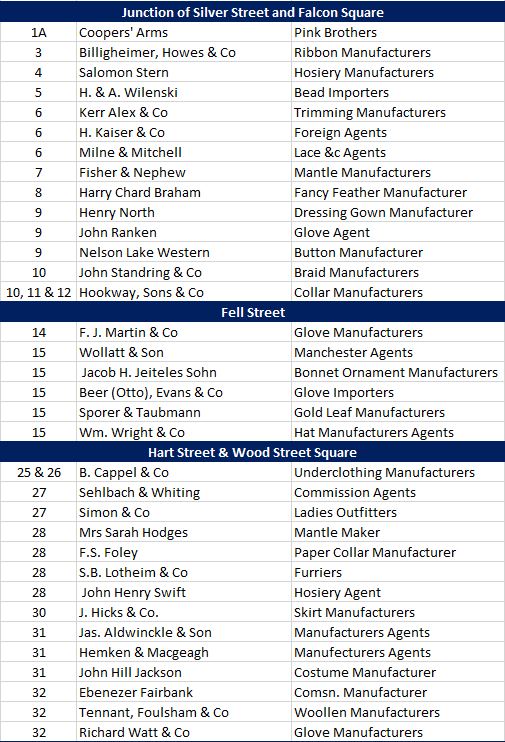

Let’s take a walk along Monkwell Street in two separate years to understand the occupancy of the street and the type of business operating in this part of the City.

Looking at two years also allows a comparison of how trades changed and how long lasting businesses were in London.

I will start at the Coopers’ Arms Public House on the corner of Silver Street, walk along the east side of the street, then back along the west side of the street, as shown in the following map:

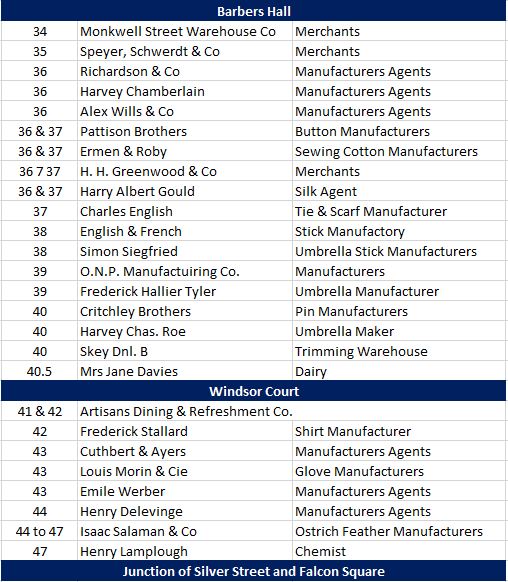

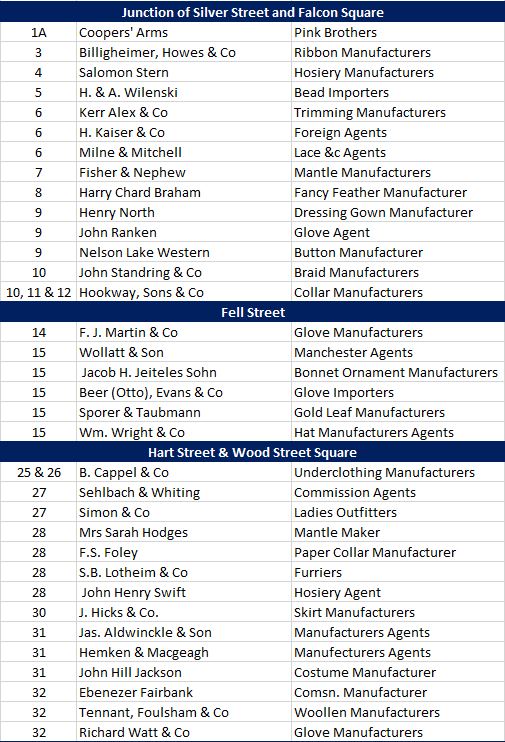

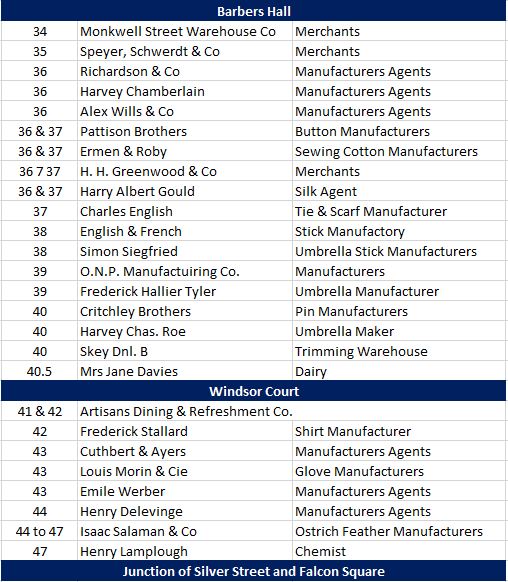

The following table is an extract from an 1895 directory, listing the building number, name of the occupying business and their trade:

With a few exceptions, Monkwell Street was occupied by companies that manufactured things that people would need in their day to day life. – gloves, shirts, umbrellas, collars, dressing gowns. They also made items that would ornament clothing such as ostrich and fancy feathers and braid.

There were a number of agents, typically in multi-occupancy buildings. I imagine these were single person or small businesses who facilitated trade between different businesses and shops.

Numbers 41 and 42 were occupied by the Artisans Dining and Refreshment Company – that is the type of name that I would expect to find for a coffee shop in east London today.

There was one strange address on the street, number forty and a half. This was occupied by Mrs Jane Davies whose trade was listed as “Dairy”, so I assume Jane Davies was running a small business selling milk, cheese and other basic products to the workers on Monkwell Street.

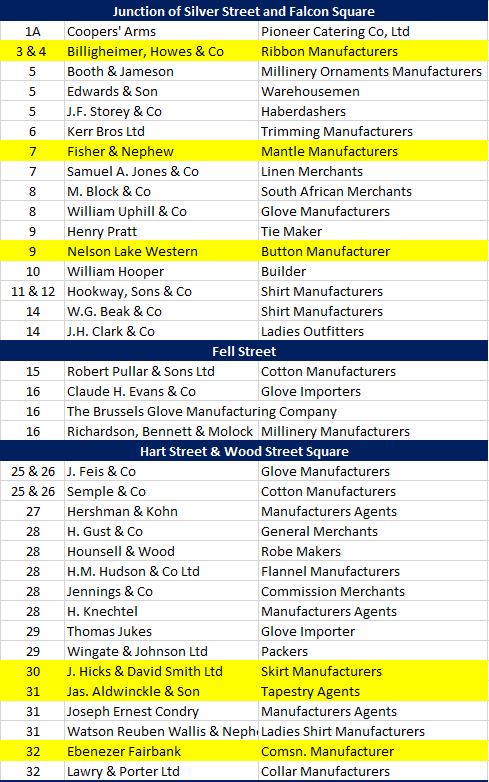

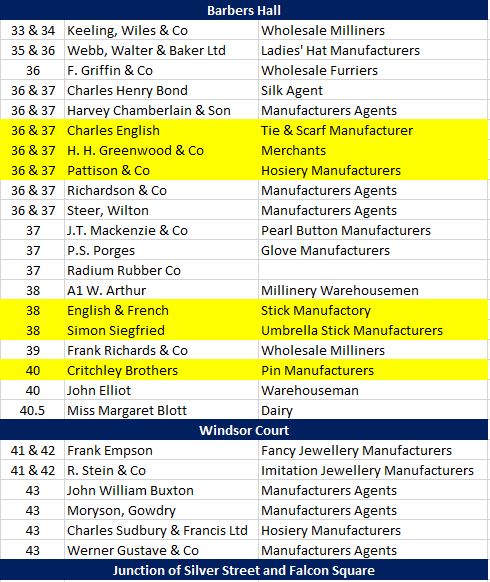

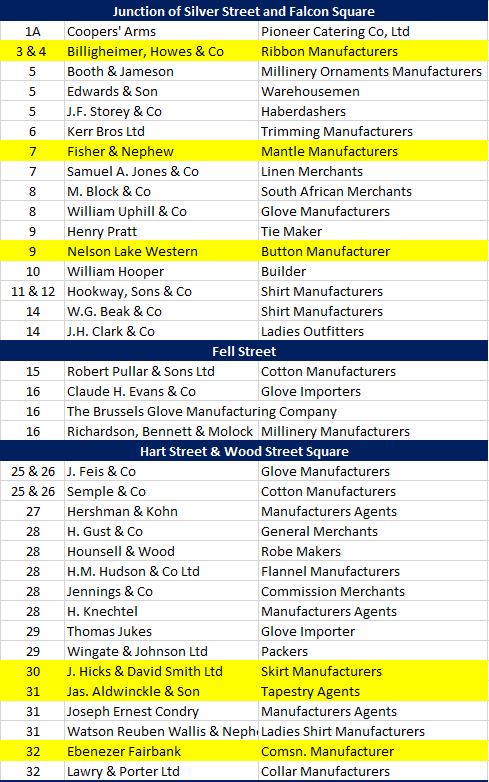

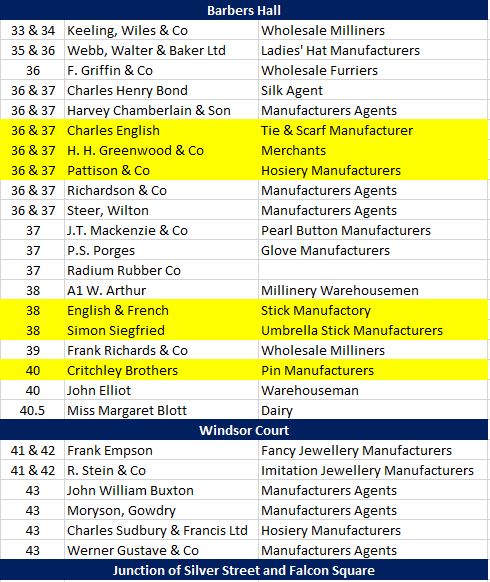

Now jump forward 20 years to 1915, and the following table is a walk in the same direction, listing the businesses occupying Monkwell Street. I wondered how many of those in the street in 1895 were still there twenty years later – I have highlighted these businesses still in Monkwell Street in yellow.

Monkwell Street was still an industrial / commercial street, as it would be until the devastation of 1940. Still with the same types of trades, manufacturing for the clothing market, and agents who must have acted as the middlemen between those who produced products and the shops that would sell them.

Of the 59 businesses in the street in 1895, only 12 were still there 20 years later. I did not include the Coopers’ Arms at number 1A or the Dairy at number 40.5, as although these were still in business, they were run by different people. For example in 1895 the dairy was run by Mrs Jane Davies and in 1915 by Miss Margret Blott.

I suspect the dairy was a job for someone who was widowed, or not yet married. In 1915 the dairy was run by a “Miss” and in the 1901 census Mrs Jane Davies was listed as a Widow. She had been born in 1853 in Machynlleth in Wales. She lived in number 40 Monkwell Street with here sister Bridget Edwards, aged 41 and listed as single. They are both listed as Confectioners, so I assume they sold more than just dairy produce.

The census also perhaps helps with the strange address of the dairy as forty and a half. I suspect the dairy was in number 40 Monkwell Street, but they used a separate door / window for the dairy business and labelled this as 40.5.

The dairy must have been doing reasonably well, as at the time of the census they also had a General Domestic Servant, 18 years old Daisy Bedford.

There is so much more to be written about this historic lost street.

It was reported that Shakespeare lodged in a house on the north east corner of Silver and Monkwell Streets, and that the pub, the Coopers’ Arms was later built on the site. He lodged there for a number of years with a French Hugenot family named Mountjoy. In 1931 it was reported that the Coopers Arms has an old inscription commemorating Shakespeare’s stay, which ran from roughly 1601 to 1606. Every pub needs a Shakespeare connection.

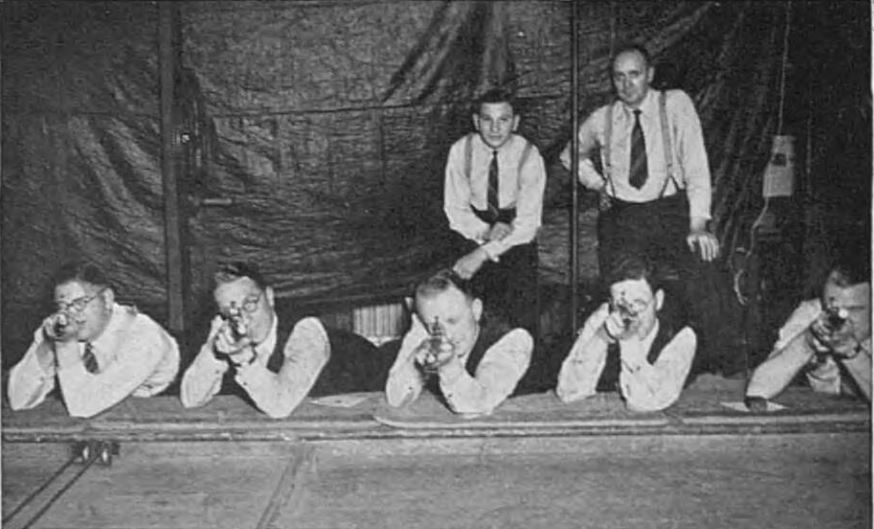

Many London pubs were also a centre of some form of sporting activity. Pubs along the Thames often supported some form of river sport such as rowing, but at the Coopers Arms it was billiards. On Saturday November 8th 1890, the Sporting Life reported that: “Last Thursday evening a large company assembled in the billiard saloon at the Cooper’s Arms, Monkwell-street, E.C. so ably presided over by Mr George Schneider. Two important events were set for decision, the first being the final heat of Mr Schneider’s Annual Amateur Handicap, for which prizes valued at £12 were given, and afterwards Mr Aldrich, a player in the front rank of amateurs, played a match of 1,000 up, three spots allowed, against Mr T.W. Horner, to whom he conceded 500, or half the game”.

There are many more newspaper reports that provide additional background to life in Monkwell Street, along with adverts for the products produced by the businesses occupying the street.

The earliest I could find was from the 28th September 1753, when: “About six weeks ago a Journeyman, who worked with Mr. Hearne, a Farrier in Monkwell Street, was bit by a mad dog, that belonged to a Jeweller in Noble Street. The said dog bit two or three other Persons who were afterwards dipped in Salt Water. They endeavour’d to persuade the Farrier to go along with them, but he seemed to make a Joke of the Affair, saying, that his Wound was but trifling, and would soon be healed; but on Sunday Morning he was seized with Symptoms of Madness, and yesterday he died raving mad“.

Other reports covered what was probably day to day life in such a street. Theft (for example one incident where 3,000 ostrich feathers were stolen), the occasional fire, and the follow up sale of damaged goods, adverts for staff and the sale or rent of premises.

Monkwell Street is long gone, after at least 800 years in this historic part of the City. The area was part of the Roman city and fort. Human occupation may have been for much longer. In London by George H. Cunningham, his final sentence in the entry on Monkwell Street is “Stone implements of Paleolithic man have been found in this street, far below the surface”.

The only part of Monkwell Street that remains today is part of the name in Monkwell Square, but at least we can stand in this quiet part of the Barbican and consider the many thousands of Londoners who have called this lost street home and workplace.

Some of my other posts that cover related places mentioned in this post are:

The church of St Mary Aldermanbury

London Wall

St Giles Cripplegate and Red Cross Street Fire Station

alondoninheritance.com