The tickets for all the walks of my new Limehouse walk sold out by Monday morning, so a very big thank you. The proceeds from these walks go towards the hosting, maintenance and research of the blog, so it is very much appreciated. I have had a number of requests for new dates, so have added two more, on the 31st of August and 10th September, which can be booked by clicking on the dates.

In 1951, my father took a couple of photos of the main entrance into St. Paul’s Church, Covent Garden:

He was far better at timing the position of the sun and weather conditions than I am, however the view is much the same today, some 72 years later:

A view of the main entrance to the church from the opposite side of the churchyard:

And the same view in 2023:

The church of St. Paul’s was one of the first buildings to be constructed as part of the development of the Covent Garden Piazza by Francis Russell, the 4th Earl of Bedford.

The Russell family were significant land owners, and within London this included the area around Covent Garden, along with significant holdings across Bloomsbury. The land at Covent Garden came into their position in 1552 when the first Earl was granted the land by the Crown.

Development of the Covent Garden Piazza and St. Paul’s Church commenced around 1630 when Inigo Jones designed the overall layout of the square. Construction of the church began in 1631 and it appears to have been completed and furnished by 1635, but was not consecrated until 1638 due to a dispute with the vicar of St. Martins-in-the Fields, mainly about the physical boundaries and the degree of independence of the new church. The Earl of Bedford had a family pew in St. Martin’s, but released this in 1635 when his new church in Covent Garden was ready.

The main entrance to the church is in Bedford Street, where the brick façade of the church can be seen between two pillars with ornate railings on either side, and providing a gate between the pillars:

Through the gates and we are into the churchyard:

The churchyard was closed to burials in 1853 and in the following couple of years all the tombstones were either removed or laid flat. The churchyard was renovated between 1878 and 1882, when the ground was also lowered and flattened.

Today, the churchyard has a wide path leading up to the entrance of the church, with seating along both sides of the path. To either side of the path are gardens and grassed spaces.

As can be seen in the above photo, the main body of the church and the churchyard are surrounded by tall terrace buildings along either side, and the church has long had a complex relationship with these buildings.

On both sides of the churchyard, there is a space between the wall of the churchyard and the adjacent buildings:

The plaque reads: “This lightwell is part of the burial ground of St. Paul’s Church. Written consent must be obtained before any use is made of this lightwell.”

Originally, the churchyard ran up to the walls of the buildings, and doors and windows in these buildings which provided access to the churchyard were long a cause of concern for the church, as there was an issue with people getting into the churchyard and causing a nuisance, as well as the general issue about security where all the surrounding buildings provided access.

In 1685, any door in these buildings onto the churchyard was ordered to be blocked up, unless it had been given permission by the church, who also then sold licences for the making of windows that looked out onto the churchyard.

During the later half of the 18th century, the churchwardens also had concerns regarding the rising levels of the churchyard due to the many people being buried, which seems to have included large numbers of non-parishioners as well as “with the remains of multitudes of Paupers”.

In the 1870s, the lightwell shown in the above photo was built, with lightwells on the north, west and south sides of the church. These lightwells served a number of purposes. They provided light into the lowest floors of the surrounding buildings, they provide a degree of security for the churchyard to prevent the churchyard being used for “various and improper purposes”, and as a benefit for the houses, they prevented “soakage” from the graves into the houses.

London churchyards must have been appalling places in the 18th and 19th centuries, and no wonder that burials were stopped in the mid 19th century. The vast majority seem to have been overflowing with the bodies of the dead, and the rising levels of churchyards gave an indication of the many thousands that had been buried in such a small space.

If we walk around the church into the old piazza and market area of Covent Garden, we get a very different view of the church:

This would have been the very visible side of the church on the new piazza that the Earl of Bedford was having built, and despite Bedford’s apparent request for a cheap church that would be “not much better than a barn”, Jones designed a grand Tuscan portico.

Whilst the portico is to the original designs, only the columns are probably original as the church was gutted by a fire in 1795, which required a significant rebuild.

The side of the church facing onto Covent Garden looks as if it should be the main entrance. When the church was built, Jones intended that it should have been the main entrance, with the altar being at the western end of the church.

This approach did not accord with the usual placement of the altar at the eastern end of Christian churches, so the entrance facing onto the Covent Garden Piazza was blocked up, and the altar is now behind this eastern wall.

The portico does though provide an excellent place to photograph the performers in Covent Garden and the large crowds that gather to watch:

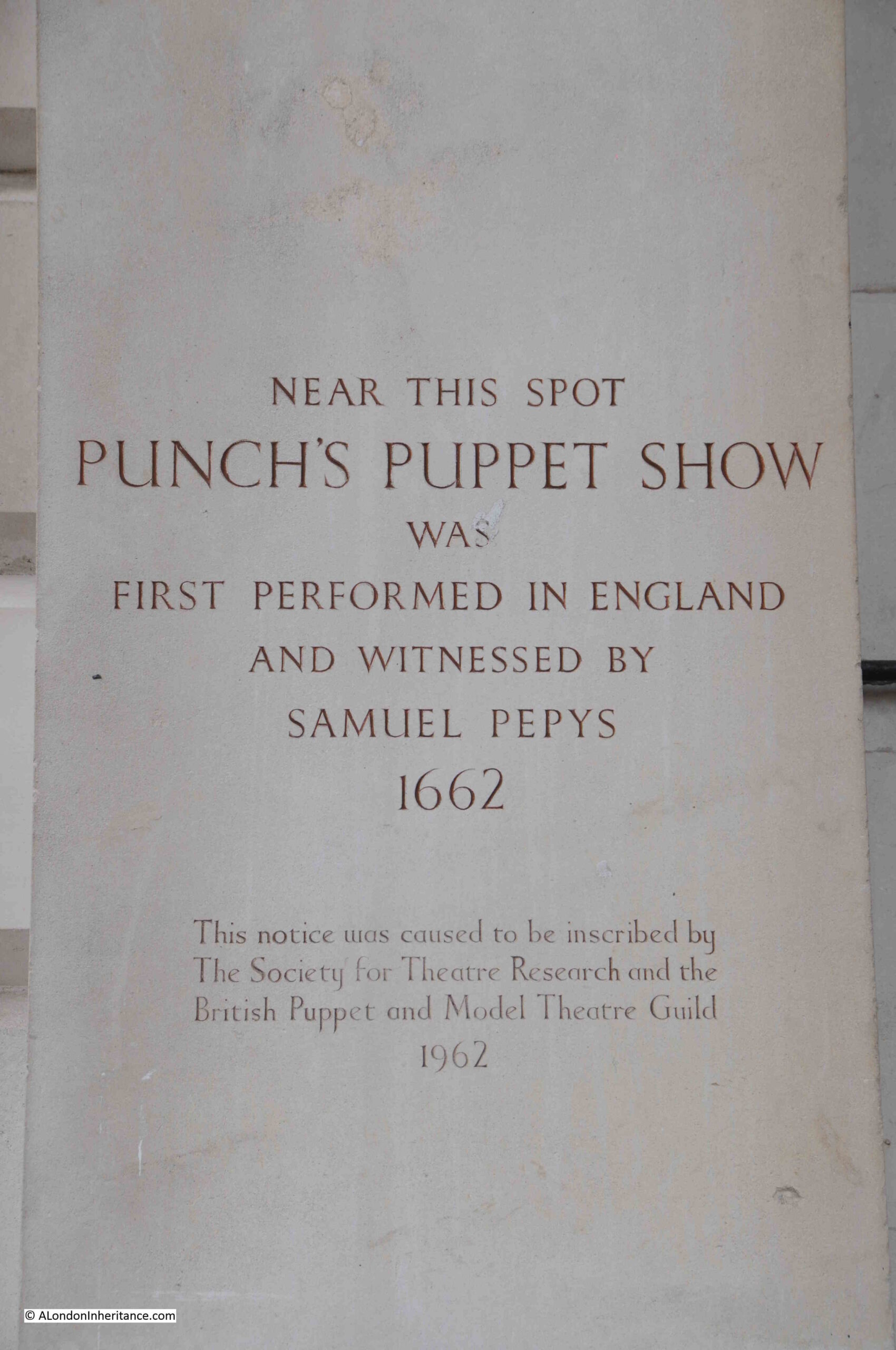

The white building above the columns is the Punch and Judy pub, and Punch has an important link with Covent Garden as indicated by this plaque on the church:

In the years after the restoration of Charles II, a number of Italian entertainers came to England, including the puppet showman Pietro Gimonde who came from the city of Bologna.

It was Gimonde who Pepys saw in Covent Garden. At the time a Punch puppet show used the form of a marionette, where strings tied to a figure were manipulated by rods above the figure’s head.

Pepys must have been impressed by the show as two weeks later he returned to show his wife, and Gimonde must have made an impression on London society as in October 1662, he was part of a Royal Command Performance for Charles II.

Punch and St. Paul’s, Covent Garden featured in the first book of the Rivers of London series by Ben Aaronovitch, when the main character, Peter Grant meets the ghost of murdered actor Henry Pyke, who also takes on the personae of Mr. Punch, in the churchyard.

Whilst the Rivers of London series is fictional, some strange, violent and sad events have happened in St. Paul’s churchyard.

The London Bills of Mortality for the week of the 22nd to the 29th of January 1716 recorded that a person was “killed by a sword at St Paul’s Covent Garden”. Bills of Mortality also recorded a number of people who were simply found dead in the churchyard – possibly those who were sick, too poor, unable to find housing or food, or perhaps just found the pressures of life in 18th century London too hard to bear.

Time to take a look inside the church, away from the crowds around Covent Garden, and this is the view when entering through the main door from the churchyard:

As with any building of such age, it has been through very many repairs and restorations that have changed the church from its original form.

In the years after completion, the roof seems to have been a recurring cause for concern, with repairs having to be frequently undertaken, with the gradual loss of the decoration and painting across the ceiling.

By the 1780s, the church was in such a state that extensive repairs were needed. The architect Thomas Hardwick was chosen from the three that put in bids for the work. The church was closed and then followed a major programme of works that expanded as more problems were found.

From an initial budget of £6,000, the final cost when the church reopened in 1789 was £11,723.

This could have been money very well spent, however just six years later in 1795, some plumbers were carrying out work in a bell turret. They left the church for a midday break and left an unguarded fire still burning.

The fire escaped to the surrounding fabric, and soon spread to rapidly to gut the majority of the church.

The church apparently looked like one of the City church’s after the bombing of the 1940s, with only the exterior walls standing, the roof collapsed and the interior gutted.

You can probably imagine the feelings of the churchwardens when they viewed the gutted church just a few years after the period of closure and expense of a major rebuild, and they were now faced with a much larger challenge, and the difficulty of trying to raise yet more large sums of money, not long after having sought funds for the 1780s restoration.

Thomas Hardwick was again appointed for the rebuild, and money to fund the project was raised by the levy of a rate of one shilling in the Pound, and by selling annuities based on the security of the local rates.

The church was rebuilt and reconsecrated in 1798.

The pulpit (on the left of the following photo) is possibly by Grinling Gibbons, or by one of his pupils. Above the altar, is a copy of the Madonna and Child by the artist Botticelli:

There seems to have been an almost continuous programme of repair work to the church, along with occasional significant restorations, including one in the early 1870s by William Butterfield, which focused on the interior of the church, with an aim of making the interior a brighter and more pleasant place to worship. Butterfield’s work included the removal of the majority of the monuments on the internal walls.

Henry Clutton, who was architect to the Duke of Bedford made a number of proposals for restoring and improving the church in the late 1870s. Clutton’s view was that Inigo Jones had almost gone along with the original Earl’s requirement for a barn-like church, with a simple brick body to the church and with only the stone portico embellishing a simple brick barn.

Some of Clutton’s proposals were taken on by the architect A. J. Pilkington in the late 1880s. The major change to the church at this time was the replacement of the ashlar exterior (square cut stones used as a facing on a wall), by the red bricks we see today.

Following Pilkington’s work, the church has stayed much the same apart from repair and decoration work. There was some bomb damage to buildings around the church, but St. Paul’s survived the war without any damage.

The font in St. Paul’s church:

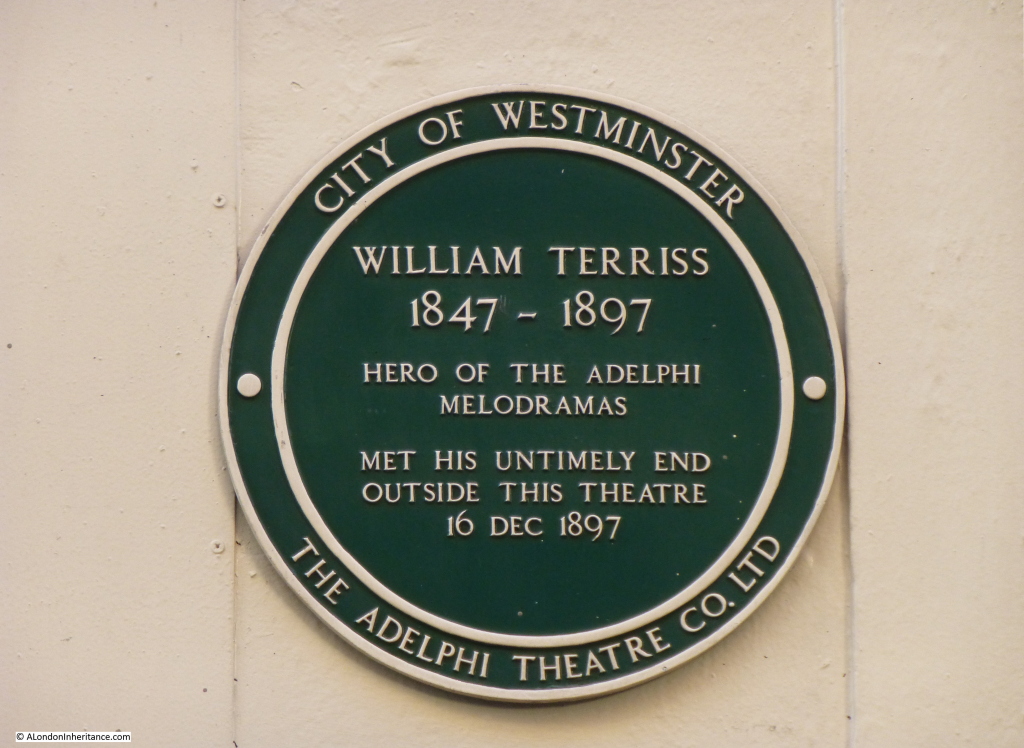

St. Paul’s Church is known as the Actors Church. The area around Covent Garden has long had an association with the acting profession. The Theatre Royal Drury Lane which was built by Thomas Killigrew in 1663, just thirty years after the church is nearby. Killigrew had received a Royal Charter from King Charles II allowing the theatre to be built.

In 1723, the Covent Garden Theatre was built. This is now the Royal Opera House.

The association with the acting profession can be seen in a number of ways. Performances are put on within the church and in the churchyard, and St. Paul’s has the Iris Theatre, its own professional theatre company.

Walking around the interior of the church and there are very many memorials to actors and those associated with the profession, including Gracie Fields:

Dame Anna Neagle-Wilcox. Usually better known as just Anna Neagle, but on the memorial including the surname of her husband, Herbert Wilcox, and below is Flora McKenzie Robson who had a long career in film, theatre and the stage:

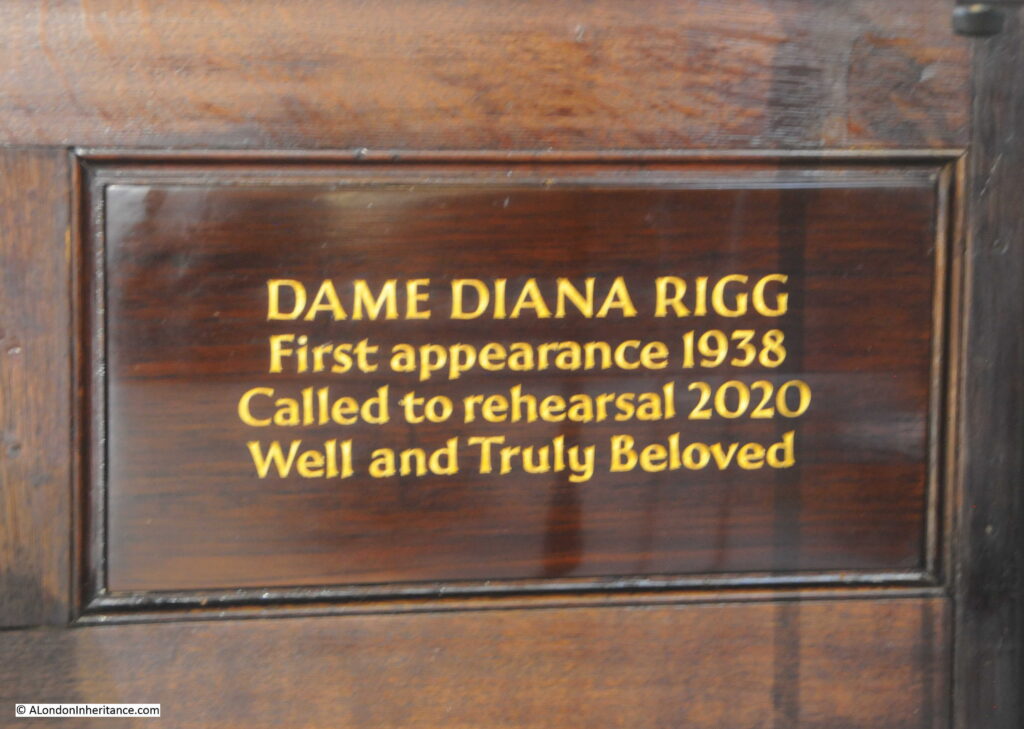

Dame Diana Rigg, again another actress with a long and wide ranging career, and who was still working right up to the year when she was “Called to rehearsal”:

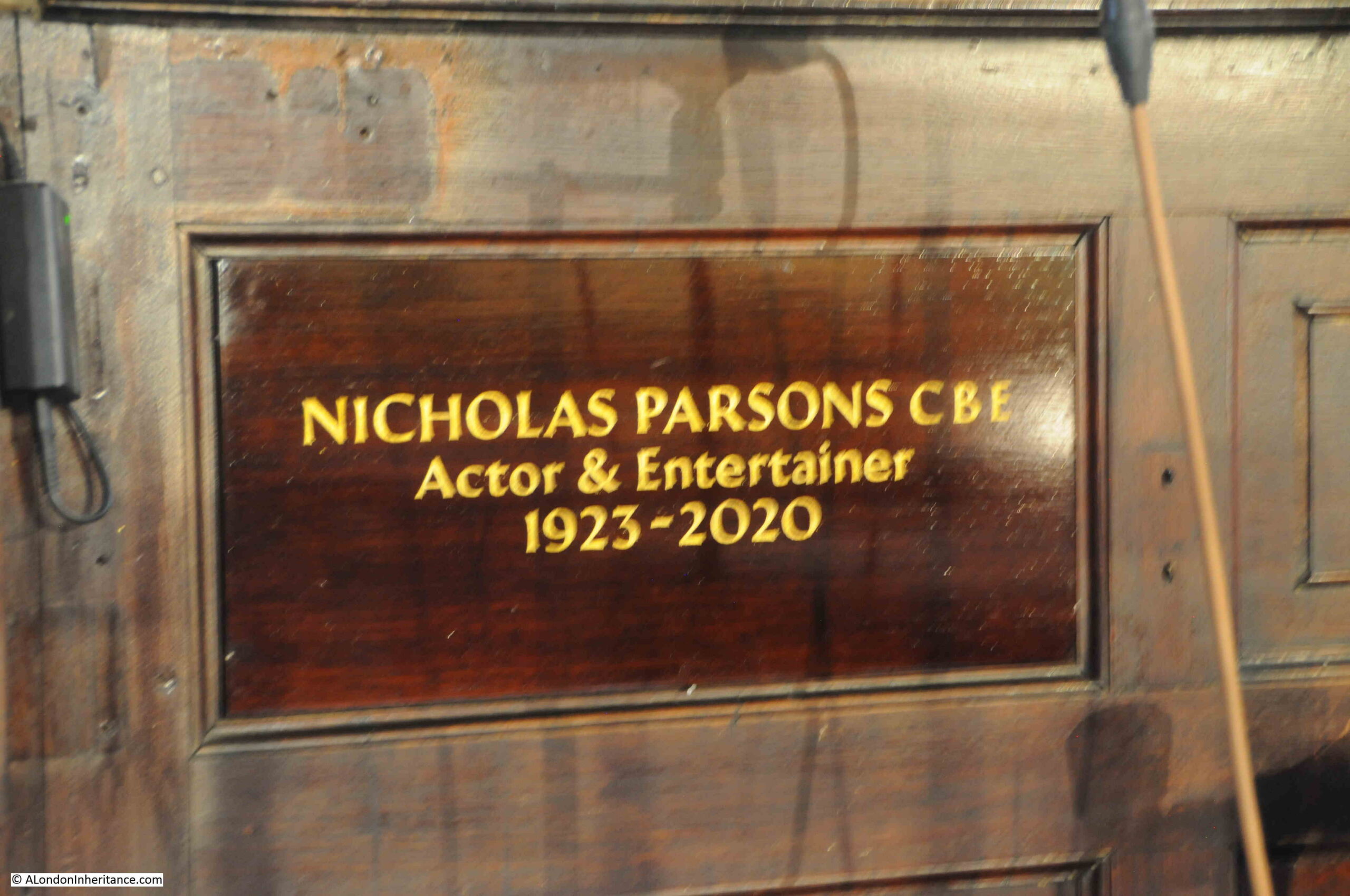

Nicholas Parsons, again another long career, and probably best known for Sale of the Century on TV in the 1970s and the BBC long running comedy show Just a Minute:

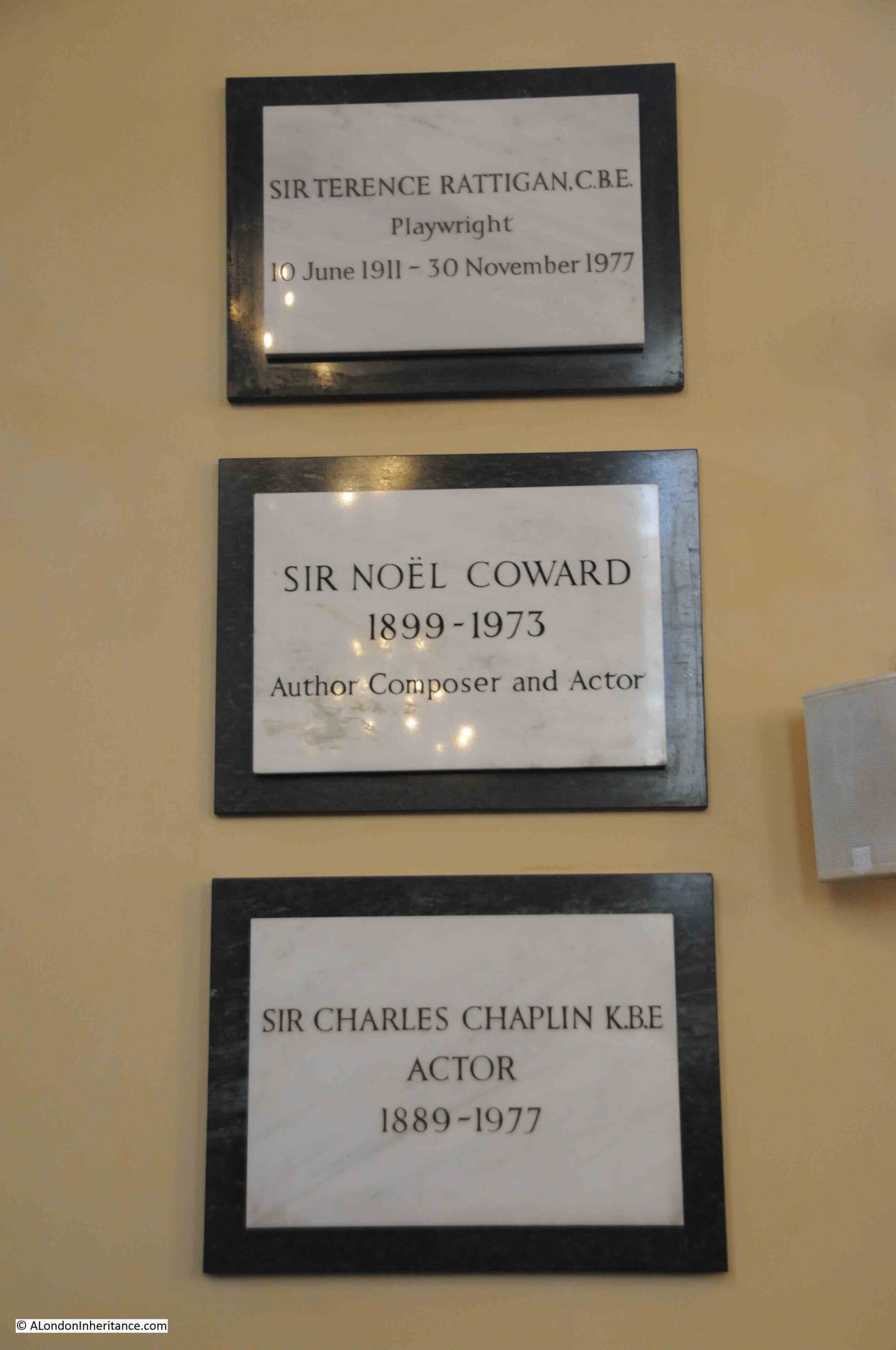

Three “Sirs” of the theatrical and film world who all died within 4 years of each other, Sir Terence Rattigan, Sir Noel Coward and Sir Charles Chaplin:

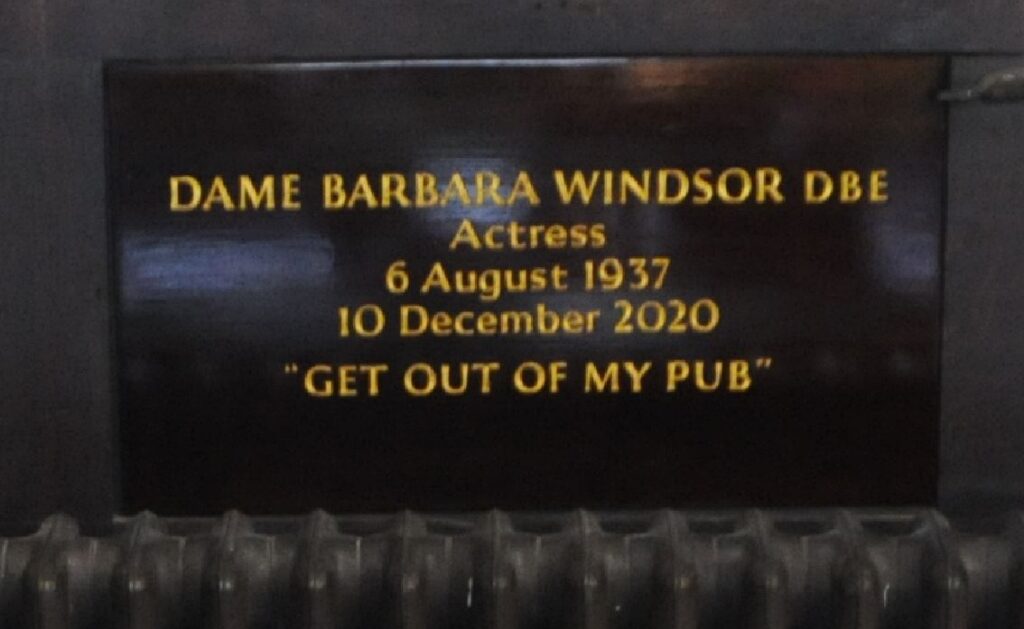

Memorial for Dame Barbara Windsor, with her well known line from the BBC soap EastEnders:

In what is a brilliant bit of placement, which cannot be a coincidence, the memorial for Barbara Windsor is located behind the small bar in the church:

Memorials to actors Roy Dotrice, Edward Woodward, Sir Ian Holm, Geoffrey Palmer and John Tydeman, a former BBC Head of Radio Drama:

There are very few early plaques remaining in the church, as mentioned earlier in the post, William Butterfield’s work on the church in the 1870s removed many of the monuments that lined the walls of the church. A few remain including that of Thomas Arne, who wrote the music for a large number of stage works between the years 1733 and 1776, including works performed at Drury Lane and the Covent Garden Theatre.

Thomas Arne also put the words of a poem by James Thomson to music, to create the song Rule Britannia, as is recorded on his memorial, which also records that he was baptized in the church and buried in the churchyard:

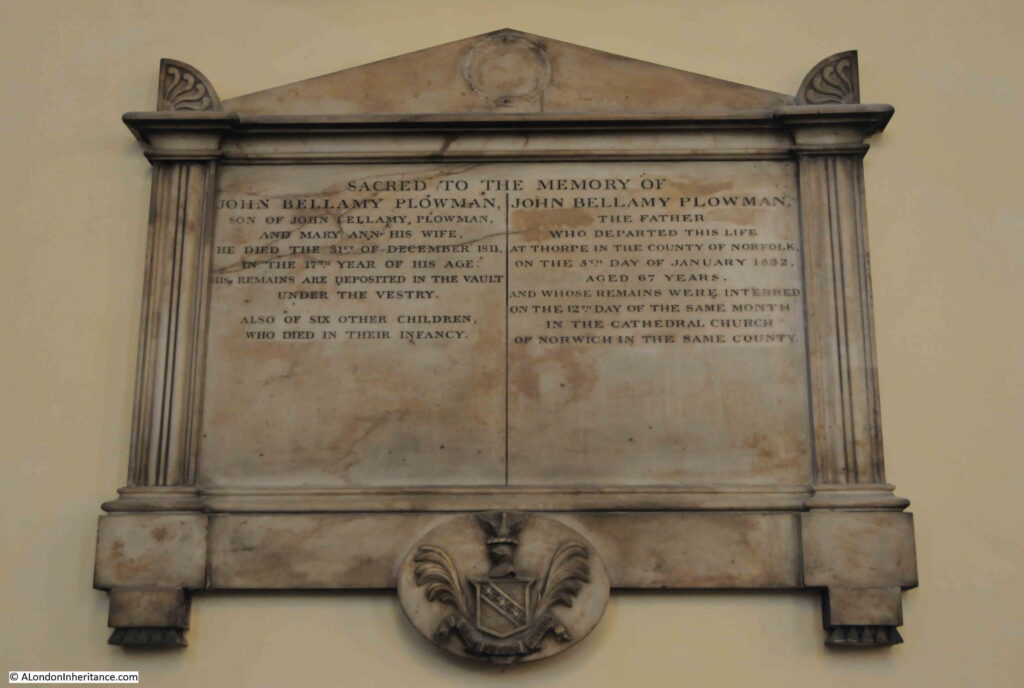

There are very few memorials to those outside of the entertainment industries. One though records the dreadful death rate of children. On the right is recorded John Bellamy Plowman, the father who died aged 67, however on the left is what must have been his oldest son, also called John Bellamy Plowman who died aged 17 and was buried in the vault under the vestry, along with six other children who all died in their infancy:

View of the rear of the church, with organ and gallery.

There were once galleries down either side of the church which provided additional seating at an upper level. These must have made the church seem very crowded when full, and they were removed during an early restoration.

St. Paul’s Covent Garden will soon be 400 years old. Although it was rebuilt significantly after the fire in 1795, and restored and repaired many times over the centuries, it still is an Inigo Jones church, and goes back to the time before the market, and when the Piazza was first established.

It is also a church that connects to the profession that is still so important in this part of London.