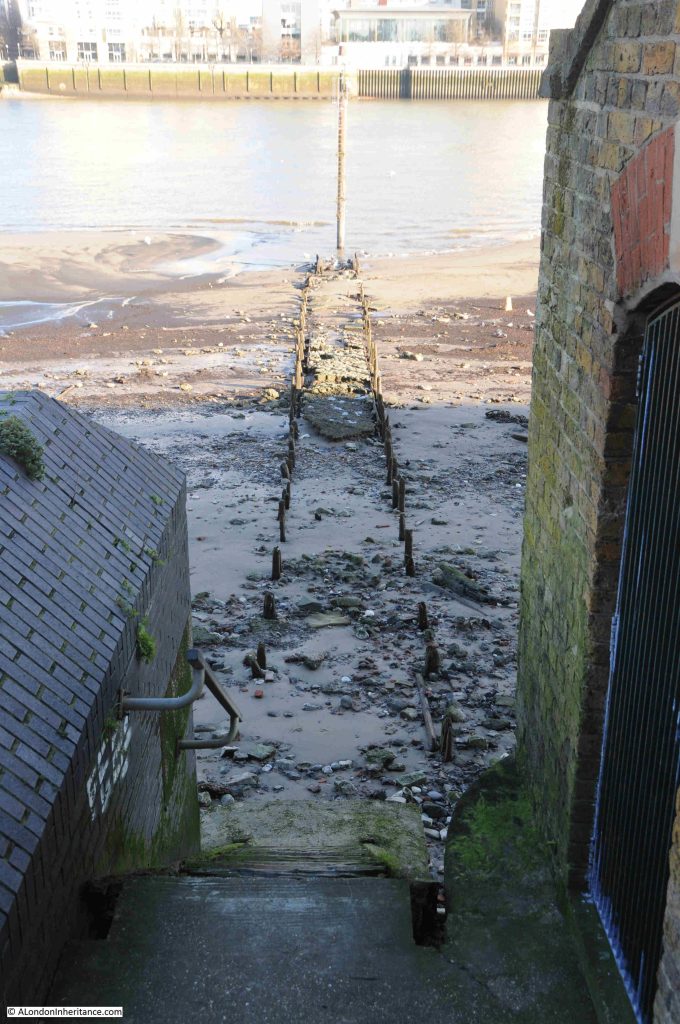

I am in Rotherhithe this week, to visit another of the Thames Stairs that have lined the river for centuries, and to explore the history of the stair’s surroundings. This is Pageant or Pageant’s Stairs, back in January 2024, when the concrete floor at the top of the stairs, as well as the stairs leading down to the foreshore, were all covered in a layer of ice:

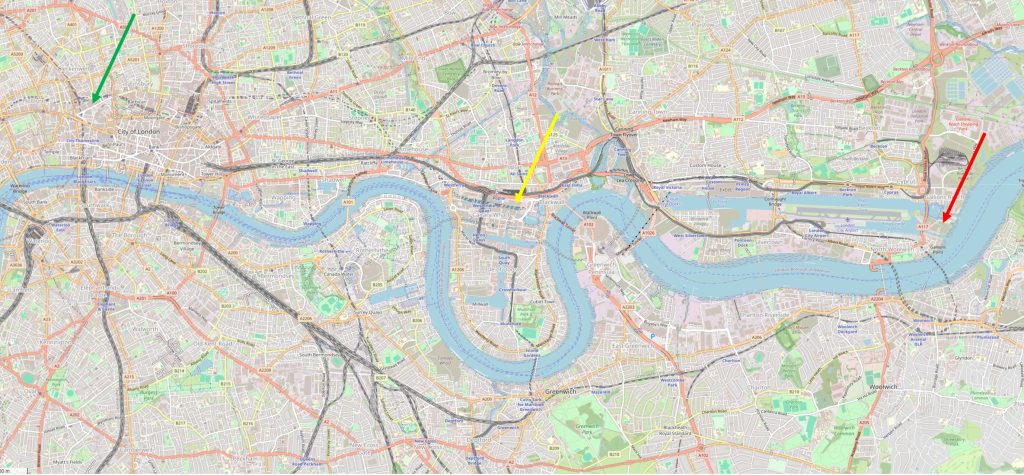

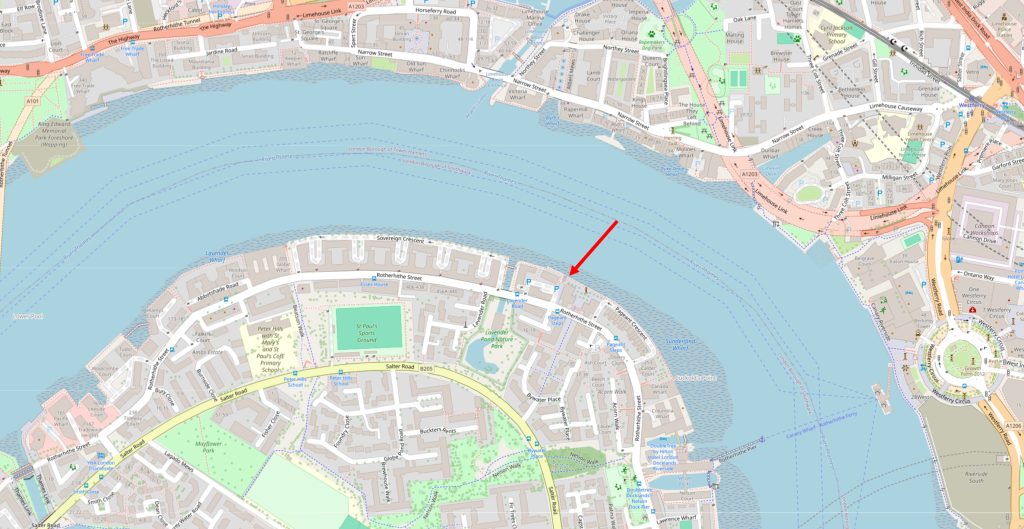

I have marked the location of the stairs with a red arrow in the following map, on the southern side of the river, opposite Limehouse (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

Pageant Stairs are shown in the 1914 revision of the Ordnance Survey map, at the end of an alley that leads between a fire station (yellow oval), and a public house (red arrow) from Rotherhithe Street (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“):

I was pleased to find there was a public house at the entry to the alley, as this confirms my theory that almost every Thame’s stairs, east of the City, had an associated pub, most alongside the stairs, others directly opposite or adjacent. I will come onto the pub and the fire station later in the post.

Pageant Stairs are listed in the Port of London Authority list of Steps, Stairs and Landing Places on the Tidal Thames, where they are described as “Concrete steps then wood steps, concrete apron”, and the listing states that they were in use as a landing place in 1708 (although the list does not identify the source of the 1708 reference, which is a standard date throughout the list for all stairs).

The earliest written reference I can find to the stairs is from the Oracle and Daily Advertiser on the 23rd of September, 1802, where business premises at or adjacent to the stairs are for sale and listed in the following advert:

“EXTENSIVE PREMISES, NEARLY OPPOSITE THE WEST-INDIA DOCKS, ROTHERHITHE, By Mr. SMITH.

At Garraway’s, tomorrow at twelve o-clock, in one Lot. THE CAPITAL and DESIRABLE LEASEHOLD PREMISES, conveniently situate for stores, in front of the Thames, at Pageant’s Stairs, Rotherhithe, late in the occupation of Messrs. Giorgi and Co. Chemists and Refiners; comprising a substantial dwelling house, garden, and small paddock, wharf and extensive warehouses for trade and merchandise; coach-house and stabling for three horses, well planned laboratory, drug, camphor and saltpetre-room; also a large warehouse, adjoining, in front of the Thames.”

So at the very start of the 19th century, the area around Pageant’s Stairs was already industrialised, with one of the many companies working in the chemicals industry that occupied the banks of the river, east of the City.

The 1802 advert mentions that the extensive premises included a substantial dwelling house, garden and small paddock. This is indicative of the semi-rural and small scale nature of the businesses along this stretch of the river as they developed during the late 18th century. Throughout the 19th century, the scale of industrial development would increase considerably.

A year later, Pageant’s Stairs are mentioned in the Evening Mail on the 18th of May, 1803 where the stairs are included in a listing of “Table of the New Rates of the Fares of Watermen”, with a rate “from Iron Gate to Duke-Shore stairs or Pageants, Oars 1s, Sculler 6d”.

Iron Gate Stairs were where Tower Bridge is today, and the stairs were rebuilt under the bridge (see this post). Duke Shore Stairs were on the northern side of the river, almost directly opposite Pageant Stairs.

Pageant’s Stairs were also frequently mentioned when recording events on the river, such as an 1870 report on the discovery of a body in the river by four young men who were rowing a boat. The location was given as being near Pagent’s Stairs, Rotherhithe.

In this article, the name was spelt Pagent, rather than Pageant, and this different spelling also seems to have been in use, but not as much as the far more frequent Pageant, sometimes with an ‘s.

The current build of the stairs, is, I assume, from the late 1980s / early 1990s redevelopment of the area when the residential buildings that now line this stretch of the river were built.

The approach to Pageant Stairs is up a series of steps, which form part of the river wall, and give an indication of the potential for high tides along this stretch of the river:

Alongside the stairs, we can see how they have been built within a walled surround, a way of continuing the river wall around the stairs:

It is not clear where the name Pageant originates. There was a wharf to the side of the stairs called Pageant’s Wharf, so the name may have come from the wharf, or the wharf took the name of the stairs.

The earliest written references I can find to the wharf date to around the same few years as the first written references to the stairs. This first reference to the wharf comes from the Morning Chronicle on the 17th of December 1804, and includes a possible alternative name of George’s Wharf:

“Twenty New Gun Carriages and Beds, nearly completed, to carry 18-pounders, Stock of Wrought Iron, Oak ad Elm Timber, Fire Wood, &c. Pageant’s Wharf, Rotherhithe. By Mr. Hindle, on the premises known by Pagent’s or George’s Wharf near the Board of Ordnance, Rotherhithe, tomorrow at 11.”

The stairs, wharf and name are almost certainly older than the above newspaper references, and it is probable that there was a wharf here in the late 1600s.

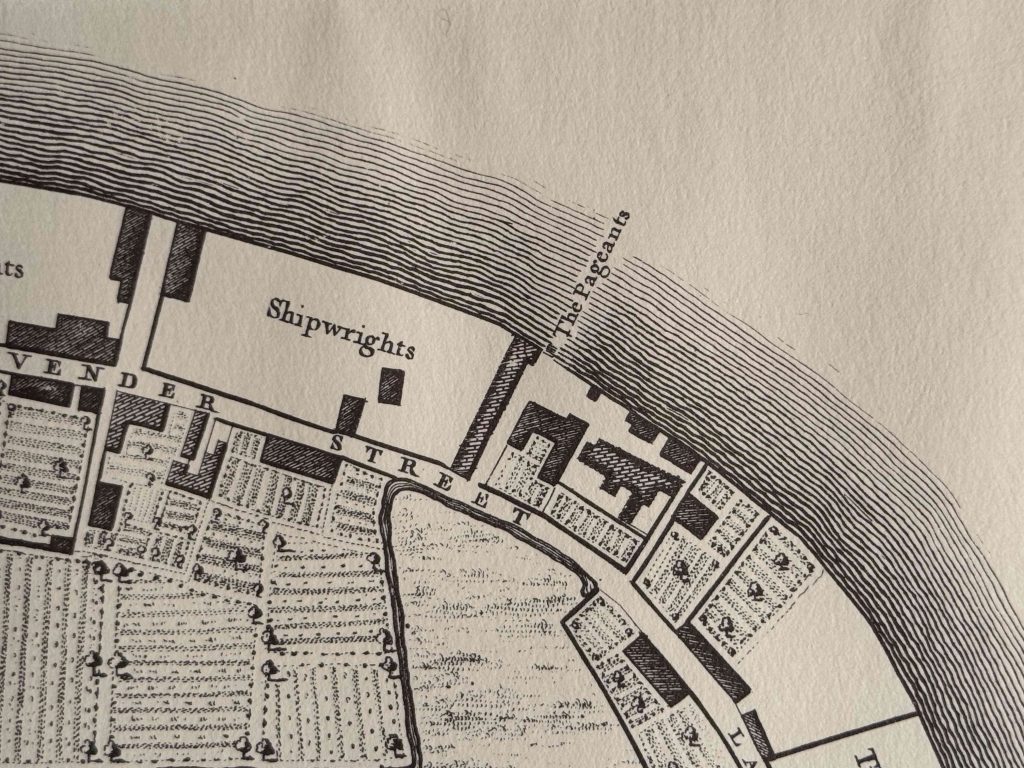

Rocque’s map from 1746 shows some short lines indicating stairs, leading down onto the foreshore, along with the name, The Pageants (in the centre of the following extract):

It is interesting that in the above map, to the east of the Pageants, we can see a plot of land almost as described in the 1802 advert, where there are buildings and open space that almost exactly correspond to the description as “comprising a substantial dwelling house, garden, and small paddock, wharf and extensive warehouses for trade and merchandise; coach-house and stabling for three horses, well planned laboratory, drug, camphor and saltpetre-room; also a large warehouse, adjoining, in front of the Thames“.

The plural – the Pageants – in Rocque’s map is the same form as used in the 1803 table of Watermen’s rates so it is probable that this was the version of the name used during the 18th and into the early 19th century.

Whether the name refers to a person, perhaps the owner of the wharf or land at some point, it is impossible to say, but it must have been in use for at least 300 years.

I also found one reference where the name used was Little Pageant’s Wharf.

The main industry along this stretch of the river was ship building, and a wider view of the Rocque map shows that in 1746, the area between what is now Rotherhithe Street (then Lavender Street) was full of shipwrights and timber yards, whilst inland of Rotherhithe / Lavender Street, it was all agricultural. It was proximity to the river which drove the early development of Rotherhithe:

There is a brilliant little booklet by Stuart Rankin published in 1996 as the Rotherhithe Local History Paper No. 1 which has a single comment about the Pageants, that they were at one time occupied by the business of Punnett & Sindrey, who were ship breakers.

In the early 20th century, the site was occupied by a firm of timber merchants, however the site would soon been transformed, as detailed in the following extract from the Southwark and Bermondsey Recorder on the 2nd of April 1926:

“BERMONDSEY BOROUGH COUNCIL – NEW DUST DESTRUCTOR TO BE PROVIDED IN BERMONDSEY AT A COST OF £19,327.

In the connection with the decision of the Bermondsey Borough Council to purchase Pageant’s Wharf, Rotherhithe Street, for the purpose of erecting a dust destructor, a specially convened meeting of the Council was held at the Town Hall on Monday evening.

The meeting was called as a matter of urgency in order to expedite the work, and it was decided that, subject to the submission of the necessary estimate by the Finance Committee, the tender of Meldrum’s Ltd of Timperley, near Manchester, should be accepted for the construction of the top-feed destructor, furnaces, boilers etc. in accordance with their specification, as modified by the amended drawings as approved by the Borough Surveyor, at a sum of £11,241, and that the tender of the Building Works Manager be accepted for the erection at Pageants Wharf of a steel framed, brick filled building and a brick chimney shaft, 120 feet high, at a sum of £8,086.”

The dust destructor, or incinerator, was needed as a result of the significant growth in Bermondsey’s population, and the waste they created.

It was opened in January 1927, and was capable of handling 100 tons of household waste a day.

Waste was collected from vehicles at the entrance and carried by an overhead railway, to where the waste was dropped into steel-lined hoppers, it was then delivered to three top-feed furnaces. Steam was generated in boilers from the heat generated by burning the waste, and the steam was used to generate a “steam blast”, which created a draught through the furnaces to get the fire to the high temperatures need to burn the waste.

The dust destructor was a major construction, and included concrete piles, 28feet in length, driven down into the hard ballast below the river bed. Fascinating to think that these piles are probably still there, beneath the river bed.

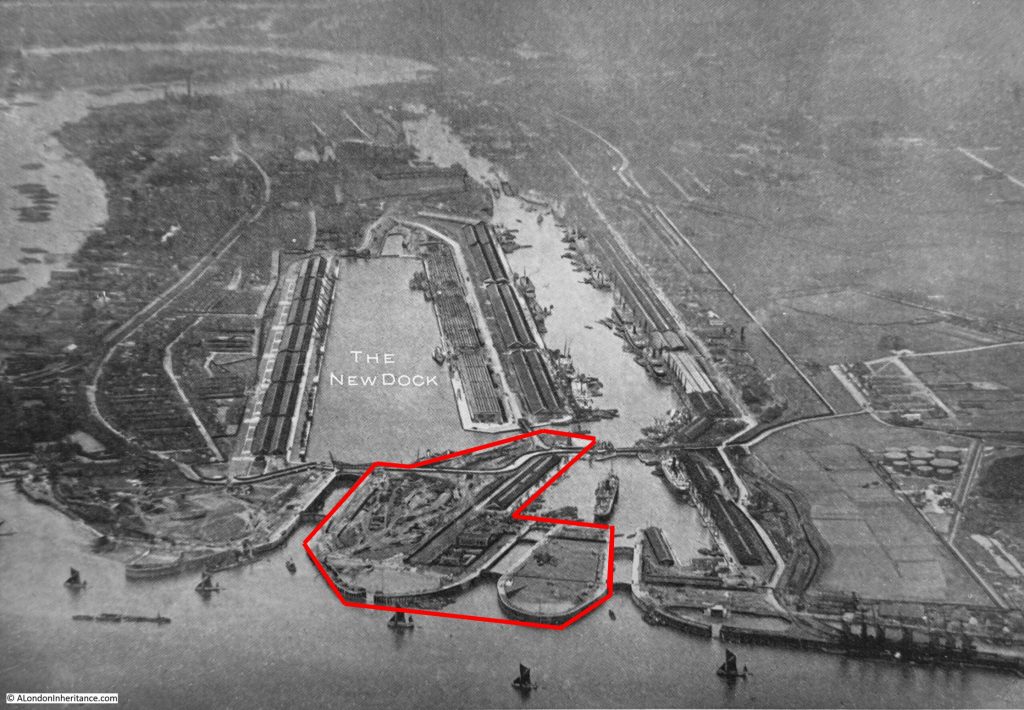

In the following 1939 image from the Britain from Above archive, I have marked the location of the chimney of the dust destructor. The image also shows how the agricultural land in Rocque’s map had been transformed into a large dock complex:

The dust destructor was to the east of Pageant Stairs , and occupied the space in the following 2024 photo:

In the above photo, there is a stone obelisk, and as far as I can tell, it serves absolutely no purpose, apart from decorative.

I have read stories about an alignment with Canary Wharf, and that the obelisk is on an alignment through the centre of the original development and the One Canada Square office tower.

I tried this on a map, and the obelisk is indeed on a perfect alignment (obelisk at the left hand end of the blue line, which then passes through the centre of Westferry Circus, then between North and South Colonnade, and passing through the centre of One Canada Square, which I have circled in blue) (© OpenStreetMap contributors:

This is almost getting into Ley Lines, or something from the excellent Rivers of London series of books, but I extended the line to the west, and it passes very close to the Bank Junction, and touches the northern edge of St. Paul’s Cathedral – two historic parts of the City of London.

No idea why the colonnade was built on an alignment with Canary Wharf, or whether it was intentional. Both developments were under the overall control of the London Docklands Development Corporation, so perhaps it was their idea to add some integration between the north and south of the river.

The view during my recent January 2026 visit, to take a look at Horn Stairs which are a short distance away:

The walkway in the above photo runs between Pageant Stairs and Horn Stairs. This was the view looking back from close to Horn Stairs. Note the name of the walk on the right given as Pageant Crescent (a bit hard to see in the gloom of a January day). Good that the name of the stairs and the wharf is still recorded here (although there is no name at the actual stairs):

During my visit in January 2024, the sky was clear, bright sunshine and very cold, with ice on the steps of Pageant Stairs. In January 2026, it was very wet, but above freezing, although a strong breeze along the river made it feel cold.

The weather has always had an impact on life on the Thames. We are familiar with the stories of ice fairs on the Thames in central London, but the river also froze, with ice and snow accumulating along many parts of the river.

In searching for stories about Pageant Stairs, I found a reference in the Morning Herald on the 20th of January 1838, which reported that “The state of the river is getting worse, and yesterday there was a continued freezing of the waters, in fact the accumulation of ice on the banks and in the stream itself, might be seen to hourly increase”.

The report went on to talk about the problems a ship’s captain had reaching his boat from Globe Stairs in Rotherhithe, due to the amount of snow and “enormous icebergs” on the river. He had to be rescued by a Thames police waterman, who cleared the snow overlaying the ice on the river and laid planks, so the captain could reach his ship.

Pageant Stairs was mentioned in the article as being the only place on the river, from Pageant’s Stairs, Rotherhithe, to Limehouse Hole on the opposite shore, which was pretty clear.

Looking down the stairs in January 2026, with only a small part of the foreshore visible:

The newspaper report about ice and snow on the river mentioned Limehouse Hole, and Pageant’s Stairs are directly opposite Limehouse, with the following photo looking across the houses in the far bank which face onto Narrow Street in Limehouse. Limehouse Hole is continuing round to the right:

The view was far better during my 2024 visit (the Grapes pub is roughly in the centre):

The following photo is of the view looking from Pageant Stairs down to Rotherhithe Street. The Public House marked by the PH in the Ordinance Survey map shown earlier in the post was at the end of the walkway, on the left and facing onto the walkway and Rotherhithe Street:

The pub was the Queen’s Head, one of two pubs with the same name in Rotherhithe, the other being in Paradise Street.

The Queen’s Head closed in 1928, shortly after the dust destructor, or incinerator was completed. This dirty, noisy industrial plant would have been to the rear and side of the pub, which was left in a small south-west corner of the plot of land with the rest being occupied by the dust destructor.

Not the best place to run a business such as a pub, although the river stairs were still in use.

Finding the Queen’s Head continues to confirm my theory that to the east of London, whether north or south of the river, there seems to have been a pub next to almost all the Thames stairs.

The Queen’s Head seems to have been a typical London pub, with all the appearances in local newspapers that you would expect, for example, from the Southwark and Bermondsey Recorder on the 22nd of October 1926: “DRINKS DURING PROOHIBITED HOURS. At Tower Bridge Court, before Mr. Pope, Alexander Glencross, licensee of the Queen’s Head, 243 Rotherhithe Street, was summoned for selling by his agent, Emily Newman, intoxicating liquors during prohibited hours to Jas. Quillan and Abraham Hill”.

Inquests were held in the pub, which also provide a view of the dangers of being on the river, and the complacent way in which deaths on the river seem to have been treated,. On the 18th of July 1835 “An inquest was held on Monday night at the Queen’s Head, Rotherhithe, on the body of Edward Evan Jones, aged 27, who was drowned on Friday evening by the boat which he was in being run down by a steamer. Mr. Cumberland, warehouseman of Cheapside, who was in the boat with the deceased and three others stated that as they were coming up the river they saw the Red Rover steamer about 60 yards behind them; the people on board called to them to get out of the way; they endeavoured to do so, but the off-set of the tide forced them into the middle of the stream. The Red Rover continued her course, and her bow struck the boat nearly midship, and sunk her. Witness was thrown out of the boat, and seeing the paddle-wheel coming against him, he dived under it and escaped injury. He believed that the collision might have been avoided had not the steamer been going so fast, although the off-set of the tide appeared to be the cause of the accident. The Jury returned a verdict of Accidental Death.”

On the 23rd of July 1898, William Cummings of Francis Street, Canning Town and Hugh Lane of Alphic Street Canning Tower were in court charged with stealing from the Queen’s Head a bottle of gin, a bottle of brandy, a box of cigars, quantity of cigarettes, gold brooch, silver scarfpin. money and other articles to the value of £3.

All normal for a pub by a set of Thames Stairs.

Pageant Stairs are unusual in that there is a bus stop with almost their correct name.

On Rotherhithe Street, just opposite the walkway up to the stairs is a bus stop that goes by the name of Pageant Steps:

Although in reality, I suspect the bus stop is named after the stone steps that are part of the early 1990s residential development around Pageant Stairs and Wharf. These new stone steps lead up from Rotherhithe Street between the flats, up to the obelisk.

A real shame, as whilst Pageant is in use to name this part of the walkway along the river, the stairs from street to walkway, and the obelisk seems to be called Pageant’s Obelisk, there is no plaque at the stairs naming them. Changing the Steps to Stairs for the bus stop name would also be a fitting reminder of a place where people once took a boat to travel, and now take a bus (although the use of either Steps and Stairs seems to have been relatively common) .

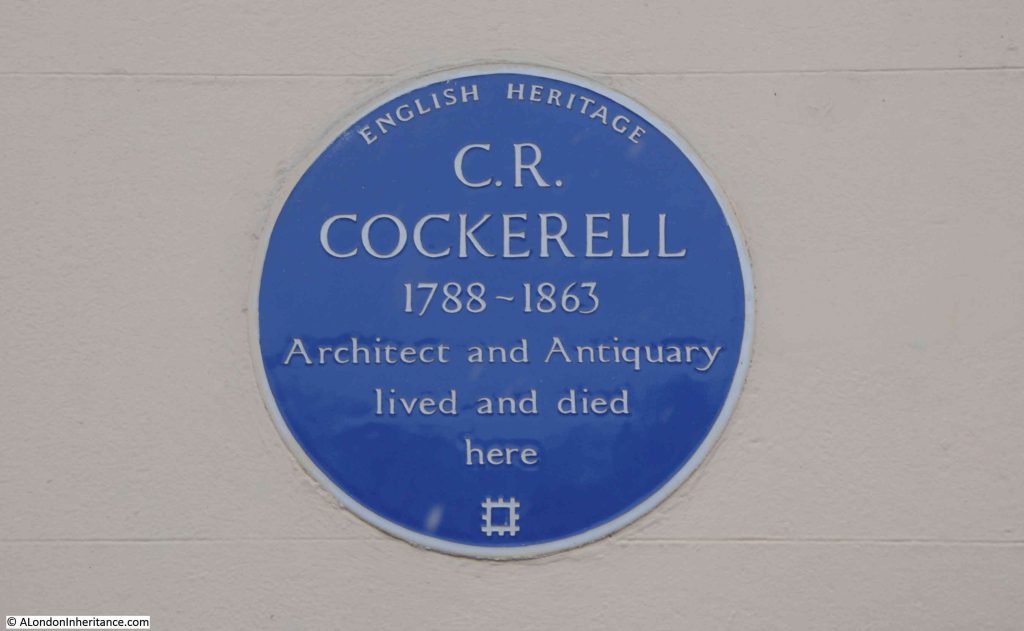

Whilst the majority of buildings and landscape around Pageant’s Stairs are the result of late 1980s / early 1990s development, there is a significant building that remains from the time before the dust destructor, and is there because of Rotherhithe’s industrial past.

This is the Pageant’s Wharf Fire Station, which can still be seen to the left of the walkway leading up to the stairs, still with the large distinctive doors leading to the space where fire appliances would be stored:

There is a plaque on the wall of the fire station, which for some reason is on the first floor, just visible in the above photo between the second and third windows on the right.

The height of the plaque and size of the lettering makes the plaque rather difficult to read, but a close up view shows that the building was restored by Barratt (the developers of the new residential buildings around Pageant’s Wharf), in memory of the crews who served at the fire station. The building, also now residential, was opened on the 25th of November, 1993:

The plaque refers to the station as “The Old Fire Station Rotherhithe”, which is a shame, as all the reports I have read about the station, from the time when it was in operation, call it either Pageant’s Wharf Fire Station, or the fire station at Pageant’s Wharf.

The foundation stone for the fire station was laid in March 1903, and news report stated that the new fire station was the result of the lack of fire stations in this part of Rotherhithe, and a recent large fire in the docks which expedited the funding and construction of the new station.

It opened in October 1903, and reports of the opening again mentioned the docks, “and the large numbers of wharves, where valuable property is frequently stored in large quantities and necessitating such protection”.

The fire station was equipped with a steam fire engine, owing to the fact that the water supply in the neighbourhood was poor. This was down to the area being mainly docks and industrial and “the amount of water required for domestic purposes is small, and consequently the pipe laid down Rotherhithe Street is of small diameter”.

The staff of the station consisted of an officer, six firemen and one coachman.

The coachman was part of the staff as fire appliances were still drawn by horses, and the fire station also had a two stall stable along with a fodder store. The first and second floors of the building consisted of living rooms for some of the staff (the earlier report when the foundation stone was laid also stated that the Coachman had married quarters at the fire station – presumably because the horses needed someone on site for their care at all times of the day).

An incident in the run up to the opening ceremony illustrates one of the problems of travelling in Rotherhithe.

Captain Hamilton, Chief of the Fire Brigade, with Mr Gamble, his second officer, along with a number of representatives and officials of the London County Council were travelling in carriages to the opening, but were delayed when they reached the Surrey Dock Bridge, as this had opened to allow a dredger to pass through.

This highlighted why a fire station was needed in the area around Pageant’s Wharf, as there were a number of lifting and swing bridges across Rotherhithe that could turn parts of the area into an island when they were lifted, thereby causing a delay to a fire engine trying to reach a fire.

I have marked the location of the lifting and swing bridges in the following map (in red) and the Pageant’s Wharf fire station (in black) in the following map (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“:

A report by Captain Hamilton, chief of the London Fire Brigade on fires in London during the year 1905, implies that the Pageant’s Wharf fire station was not that busy:

“The principal cause of fires where lives were lost was ‘children playing with fire’. Other causes are smouldering matches and other lights which are thrown down by people leaving buildings. Carelessly fitted electric circuits, temporary and inefficient fitting to gas cooking stoves and gas rings for heating glue etc. are grave sources of danger, as are also swinging gas brackets, particularly in warehouses and stables.

The busiest force station as regards calls in 1905 was the Euston Station, being turned out no fewer than 323 times. The smallest number of calls, viz. nine, was received at Sydenham, the same number being also received at Pageant’s Wharf, Rotherhithe.”

The report also stated that in 1905, across London, there had been 3,511 fires reported to the London fire brigade, and that 100 people had lost their lives in fires.

Despite the low number of calls, the station was doing important work, as in 1911 Pageant’s Wharf fire station won the Wells Cup, which was awarded to the London Fire Brigade Station which performs the “smartest job of the year”, won for the prompt way in which the station dealt with a fire which broke out in a big granary in their local district.

Another example of their work was in 1931 when firemen from the station rescued a thirteen year old boy who fell into the river and was at risk of being carried away by the tide. Firemen from Pageant’s Wharf got out on the river in a skiff and recovered the boy, who was taken to hospital.

The number of call outs at Pageant’s Wharf fire station seems to have continued to be relatively small compared to other stations across London, and there were occasional attempts to close the station, but these were successfully resisted.

The fire station was busy during the Second World War as the docks around Rotherhithe took heavy damage during bombing raids, but after the war there was a gradual reduction in call outs as both industry and the docks declined.

Closure of the Pageant’s Wharf fire station came at the end of the 1960s, although there were still attempts to keep the station open, with the swing bridges still given as a key justification, as in the following from the London Evening News on the 12th of September 1967:

“DOCKS BID TO SAVE FIRE STATION – Trade unionists in dockland are calling on the aid of their MP, Mr. Bob Melish, in a fight against a GLC plan to close a fire station in Rotherhithe. They are also writing to Home Secretary Mr. Roy Jenkins asking him to halt the closure when the council submits it for his approval. The GLC say the area can be adequately covered by existing stations and the one at Pageant’s Wharf is unnecessary.

The union men are worried that the area – a virtual island linked to the rest of Bermondsey by a swing bridge – could become cut off in an emergency. ‘If fire engines could not get to a blaze or flood quickly there could be serious damage or loss of life’, said a Bermondsey Trades Council spokesman. The unionists want the Home Secretary to order test runs of fire engines from neighbouring stations in peak traffic.”

No idea if the test runs were carried but, but Pageant’s Wharf fire station closed at the end of the 1960s, and the building is now residential, but thanks to the retention of the large doors on the ground floor clearly was once was a fire station.

It always amazes me how much there is to find in one small part of London, and the location of some Thames stairs always adds an additional layer of history.

The name Pageant remains in use, now covering the walkway along the river, the concrete steps from Rotherhithe Street to walkway as part of the recent redevelopment and a bus stop as well as the stairs, and the obelisk that has a strange alignment with Canary Wharf.

It is a quiet residential area, so different from the centuries of ship building, ship breaking, timber trading, an active fire station, and a place where the area’s household waste was incinerated.