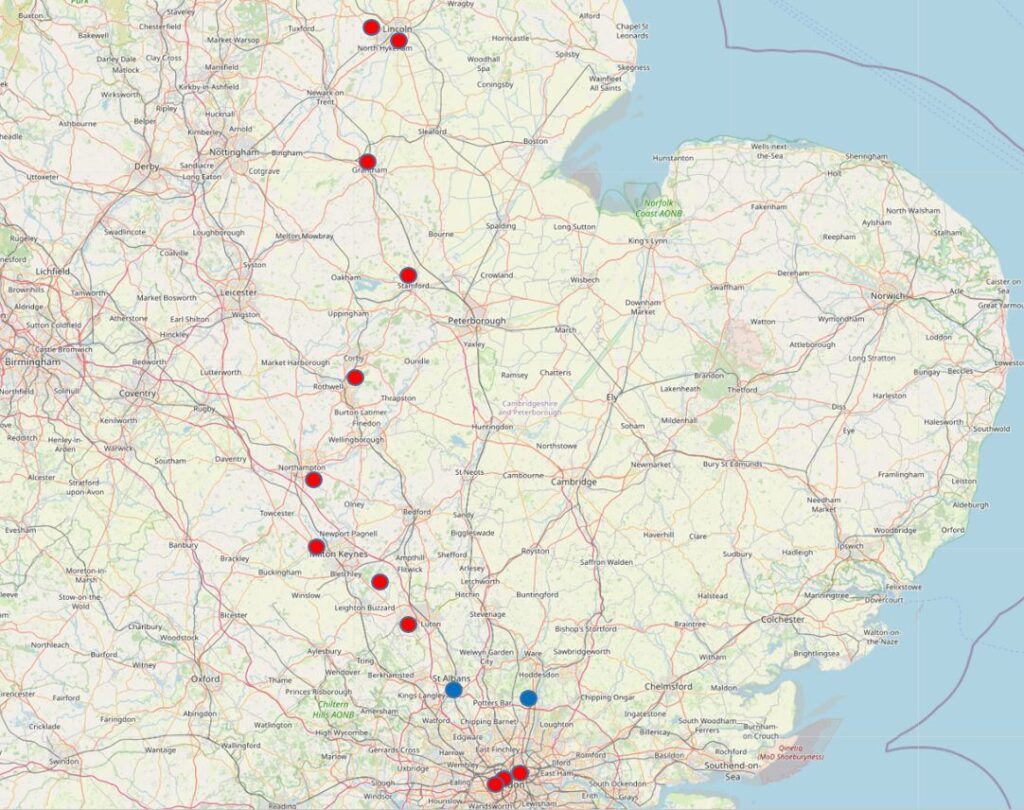

We are getting closer to London in our journey following the route of the funeral procession of Eleanor of Castile. There are just two overnight stops remaining before the procession heads to the City of London and then Westminster Abbey. These stops are at St Albans and Waltham Cross, shown as blue dots in the following map (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

Before stopping at St Albans, there is more to discover about the life of Eleanor of Castile.

The marriage of Eleanor and Edward was based on rival claims for the Duchy of Gascony, part of Aquitaine in southern France, which was part of the Angevin Empire and ruled over by English kings through the House of Plantagenet. The marriage settled these rival claims by uniting the English throne with that of Castile through the marriage.

Medieval royal marriages also had another key purpose – to produce an heir to the throne.

Having a son to take over the throne was a key concern for medieval kings. If there were no children from a royal marriage then on the death of a king there would be many competing claims from rival factions within the extended family. This would often result in conflict and confusion in the country until a new monarch was finally agreed.

Edward, being the eldest son of Henry III, therefore had an undisputed claim to the throne. The fact that he had also distinguished himself in many of the conflicts that his father had with the Barons and also on campaigns in Wales, along with Edward’s time on Crusade in the Middle East, also helped support his claim to the English Crown.

The fact that it was just under two years from Henry III’s death, to Edward’s return to England and his coronation shows that there was no competition for the crown.

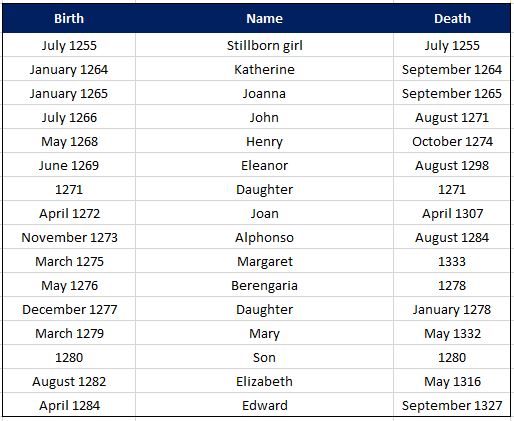

In carrying out this expectation of a Queen, Eleanor had 16 children, the first, a stillborn girl, when she was at the ridiculously young age of 14.

Thankfully there then appears to have been a gap of 9 years before the first of her remaining 15 children would be born.

Her children are listed in the following table:

The table shows that from 1263 to 1284, Eleanor was in an almost permanent state of pregnancy. This was in addition to travelling with Edward on his various campaigns and royal visits, including his time on Crusade, when Eleanor was still giving birth as they travelled across Europe and the Middle East.

The table shows the very high early death rate among her children. Her last child, Edward, born in April 1284 would be the surviving son, who would become Edward II. All Eleanor’s other sons died at a relatively young age. The only other son that lived to any age was Alfonso who died at the age of 11. If he had of lived, England would have had a King Alfonso I rather than an Edward II.

Her children are part of one of the two main criticisms of Eleanor. She was said to be rather detached from her children, and would not hurry to be by their side, even when one was close to death.

The other criticism is in how she acquired an extensive holding of properties across the country. One of the methods used was that if a property owner was in debt, and could not pay, she would cancel the debt, and take the property.

It is obviously impossible to know the true character of someone from the 13th century, however, from my reading (sources in the final post), Eleanor comes across as an educated, strong woman, finding her own way to survive in the challenging environment surrounding a medieval queen.

Regarding her children, the fact that she was pregnant almost continuously for twenty years must have been a considerable burden, both mentally and physically. During this period, she was travelling with Edward at a time when travel was not that easy.

Children would not always have accompanied a King and Queen. Boys would have been kept at safer locations until they were of fighting age, girls would have been prepared for the royal marriage market of alliances between families and countries. Boys and girls would both have been given experience of life at Court when they were at an appropriate age.

Eleanor’s approach to her children may also have been a defence mechanism given the number that died so young.

Regarding her property holdings, which were extensive, these were encouraged by Edward. Usually a Queen would have outlived a King, and it appears that Edward encouraged Eleanor to have sufficient properties so that after his death, she would have been financially independent.

Again, it is impossible to really know a person at a distance of over 700 years, and who lived in a period of the country’s history that is so very different to today.

Back to the route that the procession followed, and after leaving Dunstable, the next overnight stop was at:

St Albans

St Albans would have been a logical destination for the procession carrying Eleanor’s body to London, due to the important religious monastery that was at the heart of the town.

This had been founded in around 793 by King Offa as a Benedictine monastery. The reason for the monastery goes back to the Roman period, and Britain’s first saint who would give his name to the town.

Alban was apparently a resident of the Roman city of Verulamium in the 3rd century. Verulamium was located not far from the centre of the current town. Alban gave shelter to a Christian priest who was fleeing from Roman persecution. Alban learned more about the Christian faith from the priest and decided to swap clothes, let the priest escape and to take his place.

The priest was later caught, however Alban would not renounce his new found faith, so he was given the same death sentence as the priest, taken outside the Roman city and beheaded.

The monastery and church was rebuilt after the Norman conquest, and is unusual in that it made use of the bricks from the old Roman city, for a large part of its construction, and this is still very evident today.

An Eleanor cross was built to mark Eleanor’s overnight stop at St Alban’s, however this was destroyed, parts remaining until 1703 when these were replaced by a new market cross, which has also since been taken down.

To find the site of the cross, we had to find the site of the clock tower, which was easy to find to the south of the town:

There are two plaques on the tower. The first records that the tower is near the site of the Eleanor Cross:

The second provides some detail on the clock tower:

The clock tower is a scheduled ancient monument and is Grade I listed.

The clock tower appears to have been built due to a conflict between the abbot of St. Albans and the rest of the town. The clock tower allowed the town to sound their own hours, and the time of a curfew, independently of the abbot and the church.

The plaque makes two claims regarding French Row and the Fleur de Lys Inn. French Row is adjacent to the clock tower:

The plaque makes the claim that French troops (the Dauphin was the heir to the French throne) occupied French Row in 1216. This may be true, although I cannot find any firm confirmation. French troops did land in England in support of the Barons during their conflict with King John, and there was a French claim to the English crown at the time.

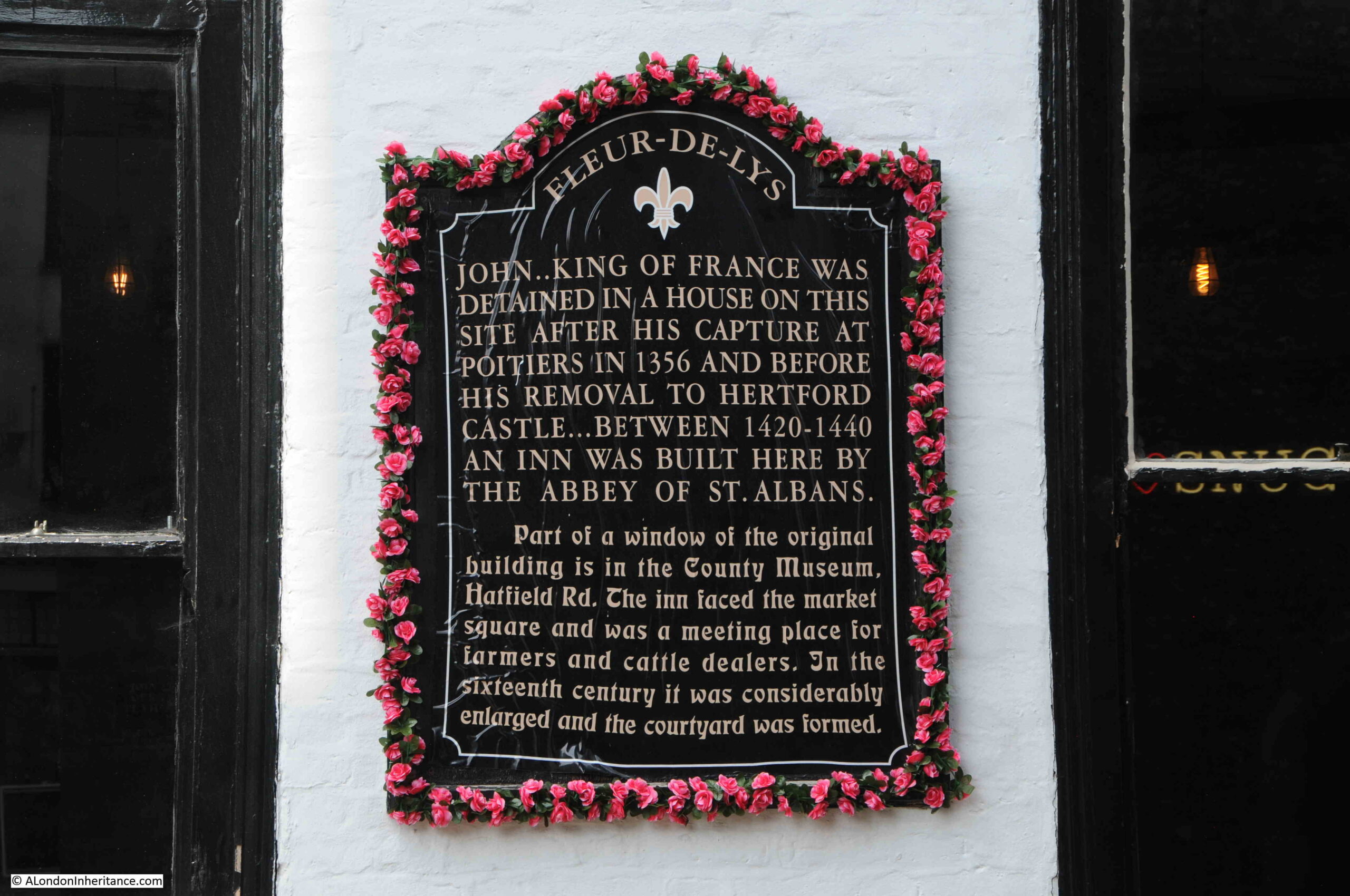

The second claim, that John, King of France was detained in the Fleur-de-Lys pub is repeated on a large sign on the front of the pub:

The St Albans Architectural and Archaeological Society has researched this claim and can “find no primary evidence for the French king’s staying in or on the site of the Fleur”.

St Albans Cathedral is a very large building that hints at the importance of the site in past centuries.

The original monastery buildings occupied the land surrounding the church. The church, and one other building which we will find later, are all that have survived, and there is a large open space south of the church that runs down to the River Ver.

As with many of the other religious buildings we have met on this journey, the monastery was surrendered to Henry VIII in 1539 during the dissolution, and the monastery and church buildings were plundered for valuables and building materials.

The church was at risk, but was brought by the town of St Albans in 1551 to become a parish church, although it appears that the church was not maintained and rather neglected. Too large a church for a small market town to support.

The church became an Abbey in 1877, and then went through a period of expensive and insensitive Victorian restoration.

The west front of the Abbey today:

A view of the tower and upper part of some of the walls shows the use of brick in the construction of the abbey, much from the Roman town of Verulamium.

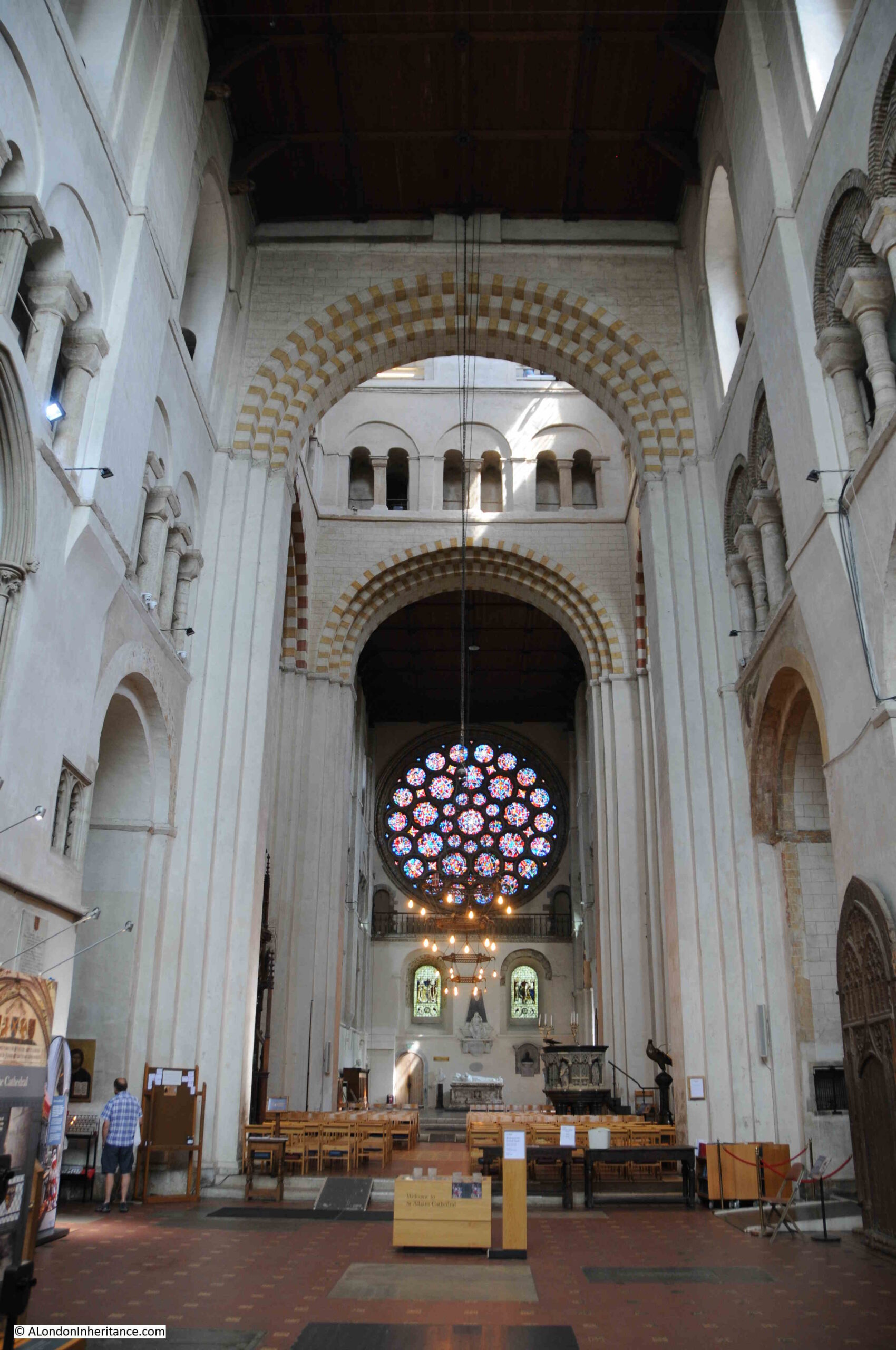

The interior of the abbey is much as you would expect of a medieval building, but has some unique decorative features:

Looking up towards the base of the tower:

There are features within the abbey that hint at the former size of the monastery. The following door once led to external monastic buildings and the Abbot would lead monks into the church through the doorway:

Graffiti which appears to date from 1668:

The nave of St. Albans Cathedral is the longest in the country at 85 metres:

On many of the columns along the side of the nave are medieval wall paintings, many of which date from the early 13th century:

So it is possible that many of these paintings were there when Eleanor’s coffin rested overnight in the cathedral.

Luckily these paintings survived the 19th century “restoration”, and serve to illustrate how decorated and colourful abbeys and churches were before the dissolution.

These highly decorated interiors suffered during the dissolution, then during the English Civil War, and again during 19th century, Victorian restoration. All these periods of change resulted in rather plain church interiors, often white washed walls, and very simple decoration at best.

The interior of the roof of the church was also decorated, and on the wall is a panel taken from the roof of the tower, that was decorated in the fifteenth century:

The Shrine of Saint Alban:

St Alban was buried on the site of the church, and a shrine was built in 1308, however this shrine was destroyed during the dissolution. Parts from the original shrine were used to build the new shrine in 1872 with additional work in 1993.

Relics of St Alban were lost during the dissolution.

The Abbey has a second shrine, this to St Amphibalus who was the Christian priest protected by St Alban. Again this is an 1872 rebuild of an earlier mediaeval shrine:

The High Altar:

The High Altar was considerably restored during the 19th century, including replacement of the statues that had originally stood in the niches across the Altar Screen.

Eleanor’s body would have spent the night in front of the High Altar, with a watch being kept over her coffin and prayers being said during the night.

Apart from the Abbey, the only other building that survived from the original monastery is the Great Gateway:

The size of the Great Gateway, as well as the Abbey, helps us understand the overall size and construction of the original monastery, as it was when Eleanor stayed there in December 1290.

Leaving St. Albans, the procession headed to the last town prior to entering the City of London. This town would modify its name due to Eleanor’s visit and became:

Waltham Cross

The destination of the procession was Waltham Abbey, a short distance to the east of Waltham Cross. The church at Waltham Abbey was an important religious centre and was reputed to be the place where King Harold Godwinson, the last Anglo-Saxon king of England was alleged to have been buried after his body was brought back to the church after the Battle of Hastings.

Waltham Abbey is to the east of St Albans, and the route south from St Albans would have been a shorter route into London, however by heading east, the procession would have been able to enter the City from the north east and therefore head through the City on the route to Westminster.

Edward I also had to leave the procession at St Albans and head directly to London, presumably to arrange the final details of the procession through the City, and the funeral at Westminster Abbey.

Waltham Cross is the site of one of the few remaining crosses, and it was built at a key cross roads where the procession would have passed from St Albans to Waltham Abbey, and then from Waltham Abbey back to pick up the road to the City

Today, the crossroads have disappeared, and the cross stands in the middle of a pedestrianised area:

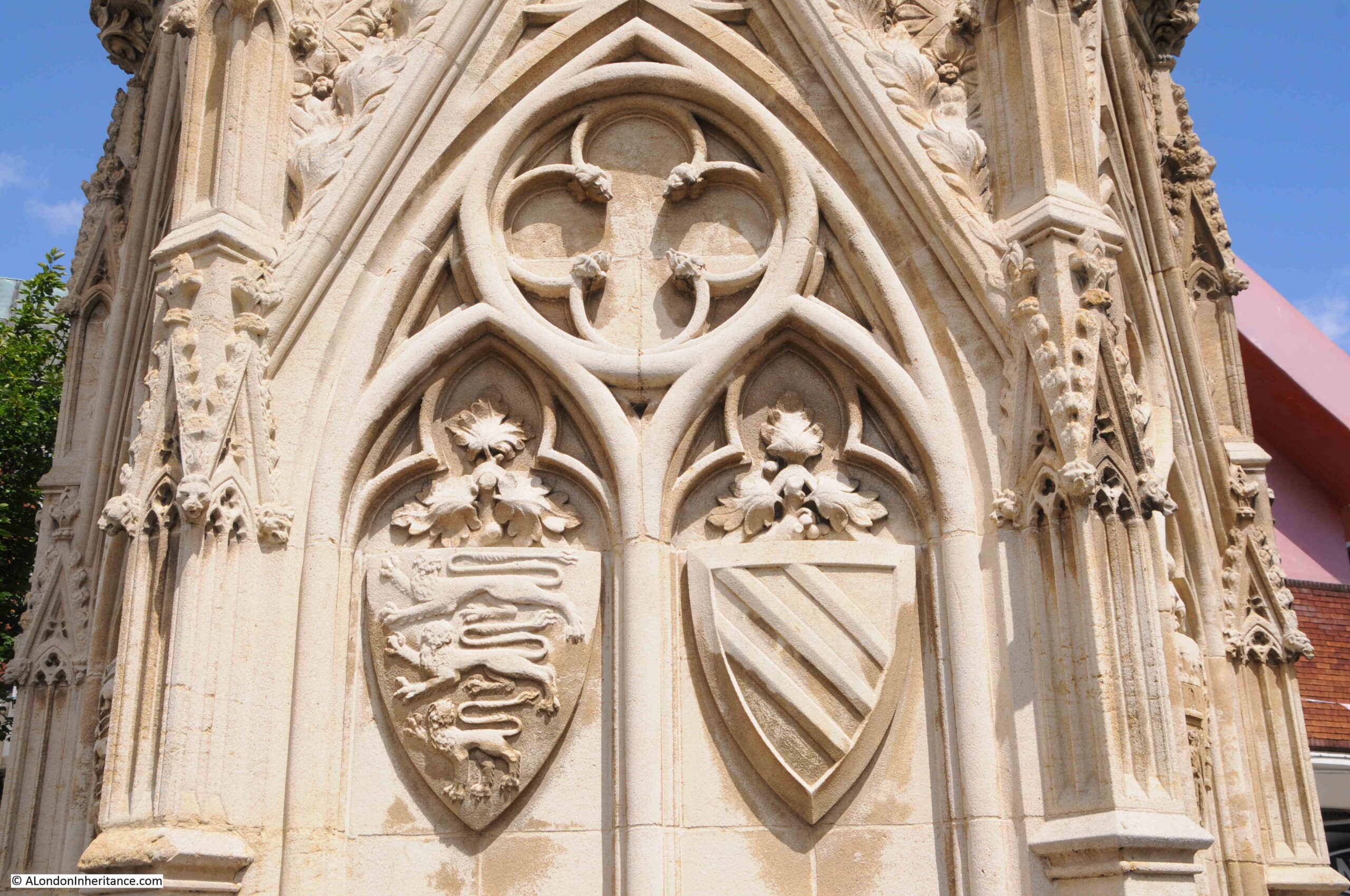

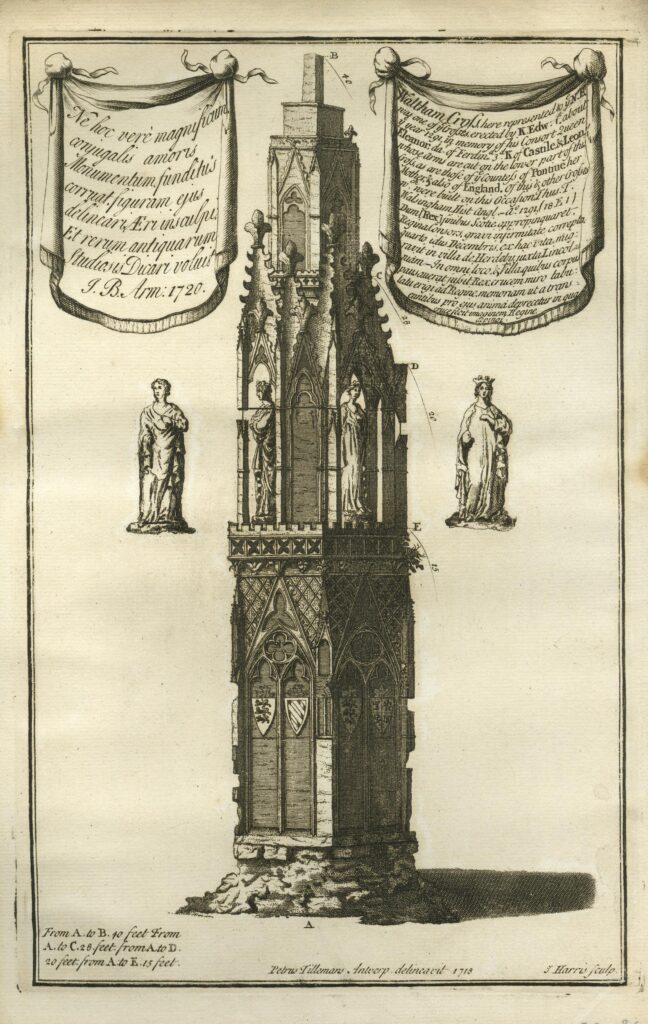

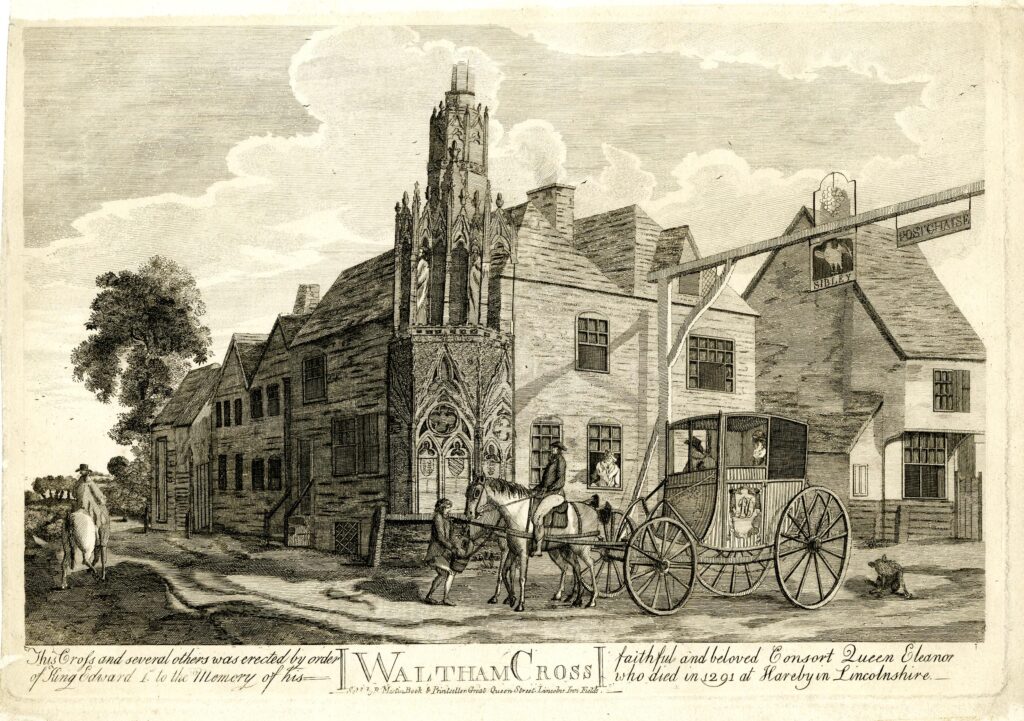

The cross has the same standard design as the other surviving crosses, with the lower tier consisting of decoration and coats of arms, above are statues of Eleanor, and above a decorated section leading to a cross.

The arms of England and Ponthieu:

The cross looks to have been significantly restored. The stone of the lower section looks to be a slightly different colour to the upper sections, and is very clean. The arms and surrounding carvings show no sign of the type of erosion which would have occurred to stone over centuries.

The arms of England and Eleanor of Castile:

Eleanor looks out from the mid tier of the cross:

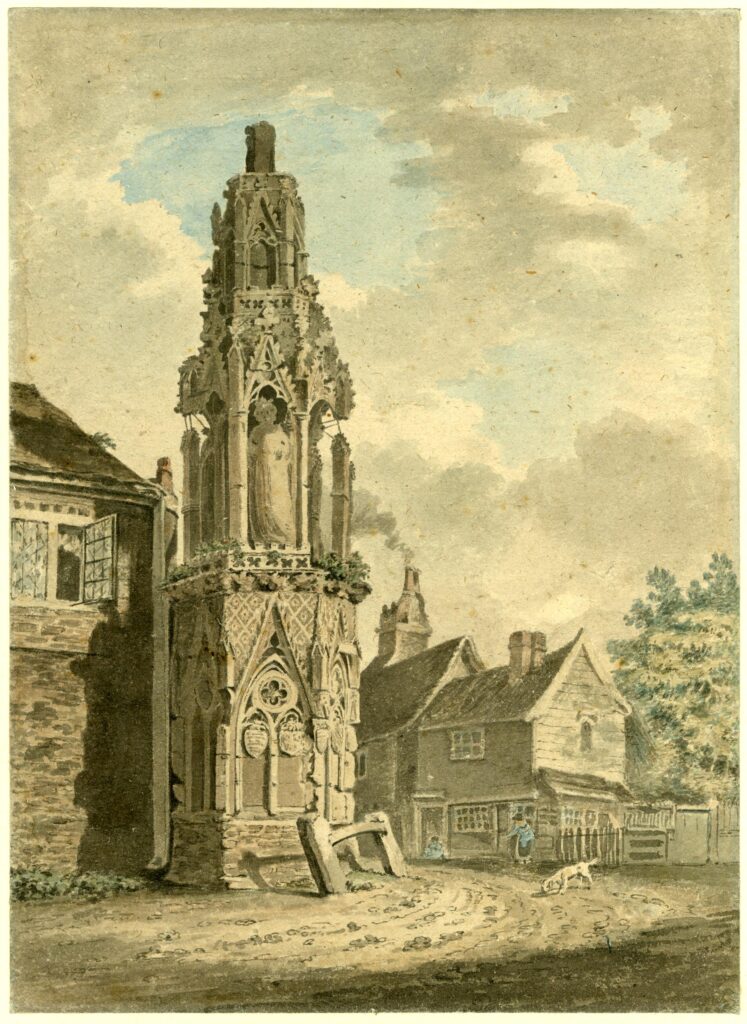

That the cross has been considerably restored, and how the area around the cross has changed, can be seen in early prints of the cross, for example the heavy state of decay in the following 18th century print (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

The cross in 1720 (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

The cross in the early 19th century is shown in the following print. This illustrates that, as with the other surviving crosses, and probably with all the crosses that have been lost, they were placed in prominent positions where they could be seen by both locals, and those traveling along the roads of the country (© The Trustees of the British Museum).

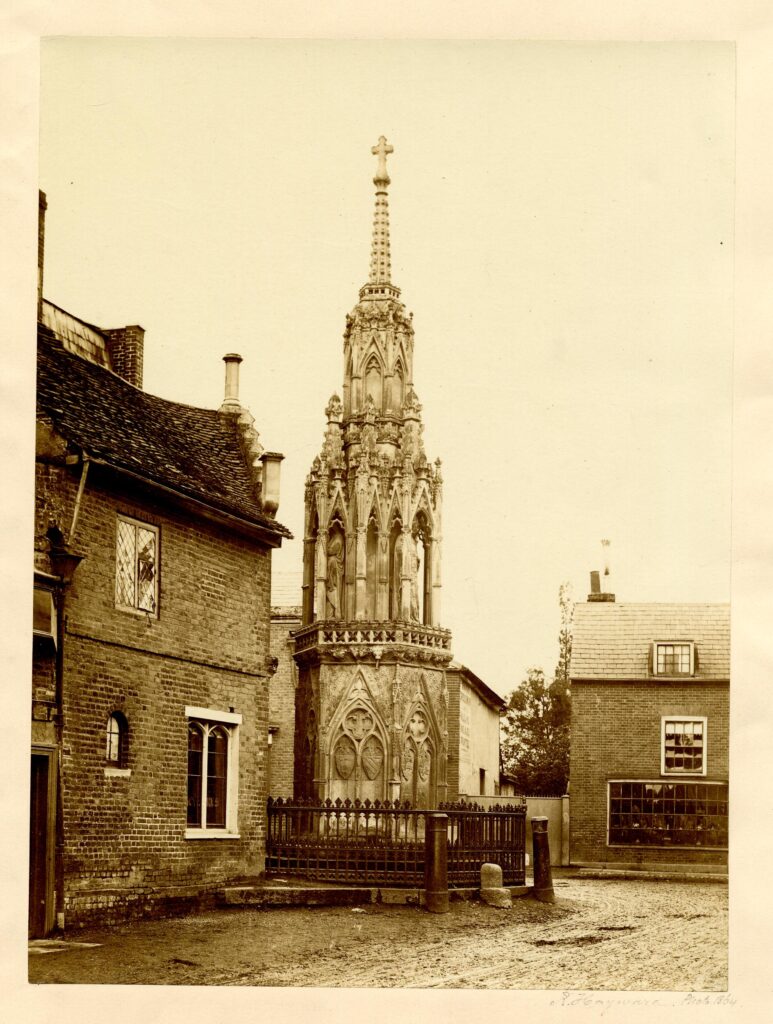

A photo of the cross from 1864 (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

Comparing the photo of the cross in 1864, and the previous prints of the cross, it would appear that significant restoration took place during the first half of the 19th century. The cross in 1864 (with a clean up) looks much the same as the cross we see today, although without the houses and the road.

As with Stamford, Waltham Cross retains an inn sign across what was the road:

This was for the Four Swans Hostelry, which was a coaching inn on the road through Waltham Cross. There was an inn sign hanging below the length of timber across the street, and on the sign was a claim that the inn dated from 1260, so if this claim was true, it would have been there when the procession carrying Eleanor’s body passed by on the way to Waltham Abbey.

Comparing the prints and 1864 photo of the cross shows a remarkable change in the area surrounding the cross. Once a cross roads, with an inn and houses, the cross now standards in the middle of a pedestrianised shopping centre:

On Thursday the 14th of December 1290, the procession left Waltham Abbey, passed through the crossroads that would later become Waltham Cross (the area in the above photo), and headed towards London, which will be the subject of the final post of this series.

Absolutely loving these posts. Such a treat through the week. Fabulous research.

You took me all the way back to St Albans from Ontario Canada. Always a favourite outing for me as a girl.

We always visited to the Abbey. Thank you for the wonderful history lesson. Looking forward to the final

episode, London where I grew up.

Must make a return visit to St Albans its been too fleeting in the past