The aim of the Festival of Britain was that it would touch as much of the population of Great Britain as possible. It would encourage the population to explore and learn more about their country, science, engineering art etc. and would use the best in design and graphic art to portray the festival. The festival symbol created by Abram Games is one of the most easily recognizable symbols for an event.

In this latest post in my series on the Festival of Britain, I want to move from the South Bank Exhibition and cover some other ways the festival involved the wider population, some of the other exhibitions and the designer behind the key festival symbol.

The South Bank was the main festival site, however there were many other activities in London and across Great Britain that were associated with the Festival of Britain along with views of the country that aligned with how the Festival of Britain aimed to portray the country.

One of the themes behind the Festival of Britain was that the people of Great Britain were a family. If you have watched the film by Humphrey Jennings and the Central Office of Information for the festival: Family Portrait – A Film on the Theme of the Festival of Britain this view of the British as a family is clearly seen.

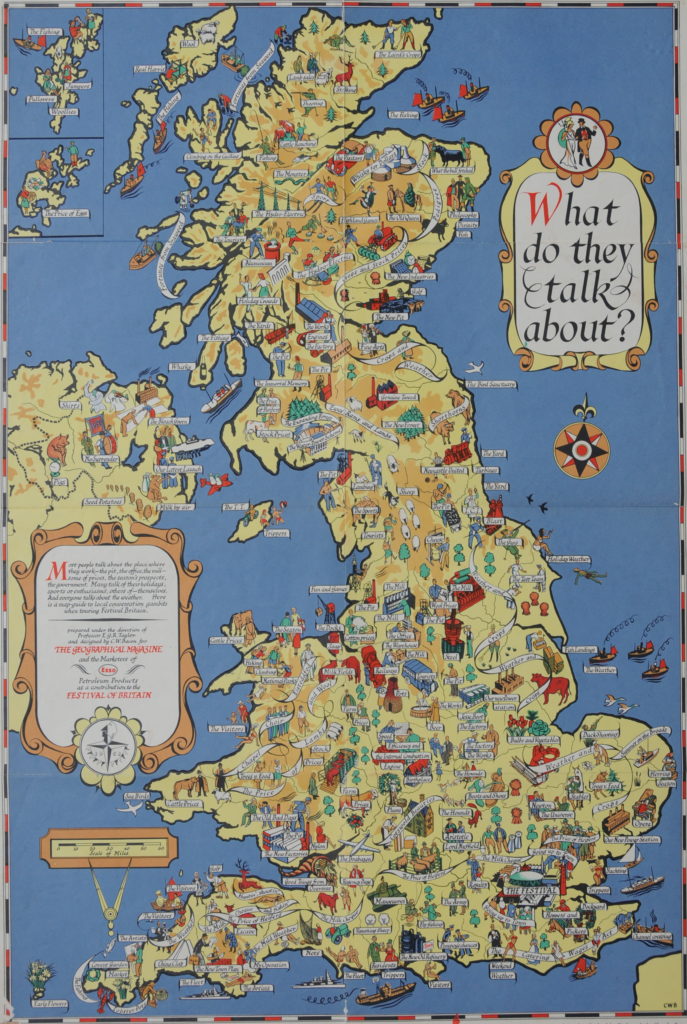

There were a number of other examples of how the country was presented as a family and with the twin themes of the Land and the People. One of these is the map of Great Britain called “What do they talk about” produced for the Geographical Magazine and Esso.

The map is shown below and the detail is a fascinating snapshot of the country in 1951 (click on the map to open a new window with an enlarged view):

The Festival of Britain South Bank Exhibition is shown in London. London is surrounded by Trippers in Southend, Royalty in Windsor, the Army in Aldershot, Hoppers and Pickers in Kent. Weather and Crops covers much of the east of England. The Pit, New Factories and the production of Nylon is shown in south Wales and in Bristol, the Bristol Brabazon, constructed by the Bristol Aeroplane Company is shown.

Shakespeare’s birthplace is shown in Stratford, Potts in Stoke, the Mill in Lancashire, Turbines in Newcastle, Hydro-Electric, Whisky and the Loch Ness Monster in Scotland.

In Northern Ireland ship building is represented by “Our Latest Launch” along with agriculture with milk, potatoes and pigs.

It is a fascinating map and it would be an interesting exercise to produce an equivalent map today to show how the country has changed since 1951.

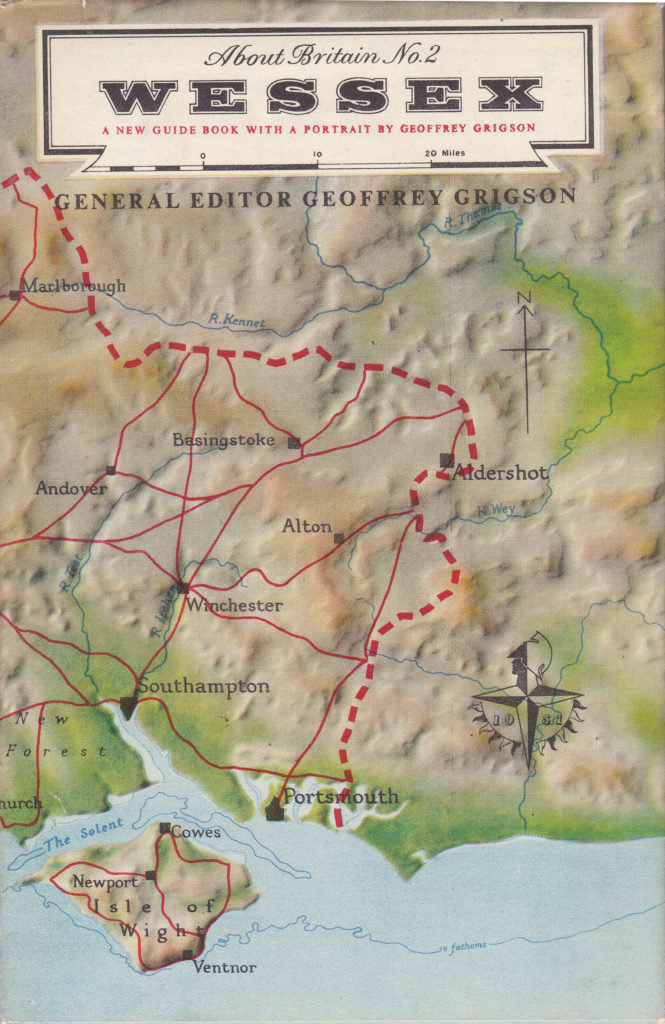

The Festival of Britain was educational and informative, and one of the aims of the festival was to encourage people to understand more about, and explore Great Britain. To help with this aim, a series of guide books were published for the festival covering the whole of the country and detailing guided tours to help explore each region.

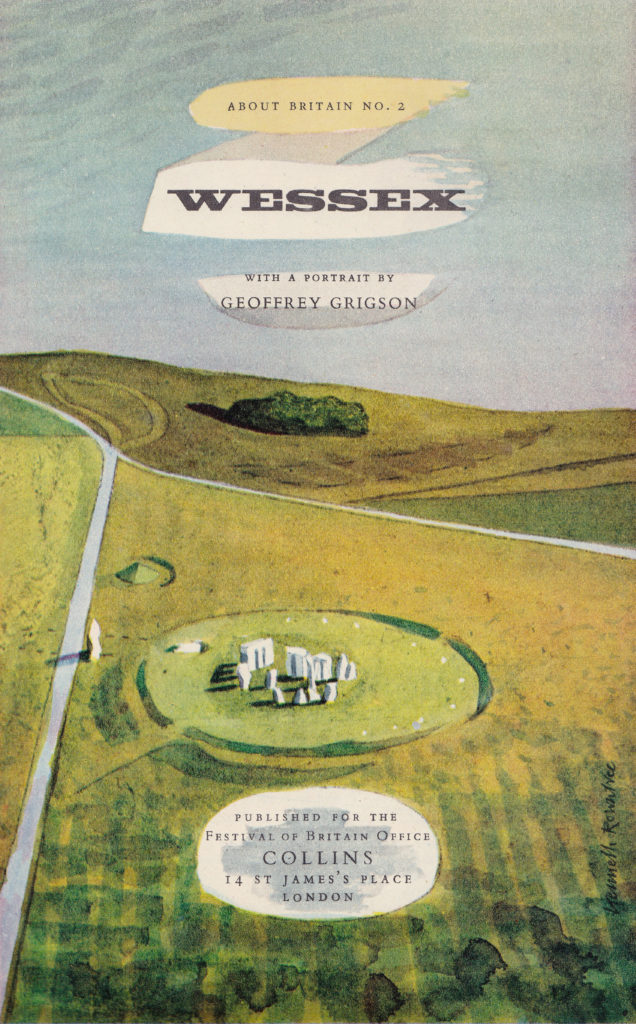

Thirteen different guide books were published by Collins covering the whole of Great Britain. The cover of the guide book for Wessex is shown below:

The “Using this book” section advises that “These guides have been prompted by the Festival of Britain. The Festival shows how the British people, with their energy and natural resources, contribute to civilization. So the guide-books as well celebrate a European country alert, ready for the future, and strengthened by a tradition which you can see in its remarkable monuments and products of history and even pre-history”.

The guide-books were priced at three shillings and six pence, a level which the publishers intended to be a very reasonable price for as wide an audience as possible. They were written by well known authors and specialists in each of the regions and the books had a coloured title page by either Kenneth Rowntree (who worked on the Freedom mural in the Lion and the Unicorn pavilion) or Barbara Jones. The title page for Wessex:

The format of the guide-books was to start with a portrait of the region being covered. This would start with a geological introduction followed by a detailed guide to the various villages, towns and cities, main features of the region, the countryside, traditional industries, churches and cathedrals and monuments. Illustrated mainly with black and white photos along with a number of colour photos.

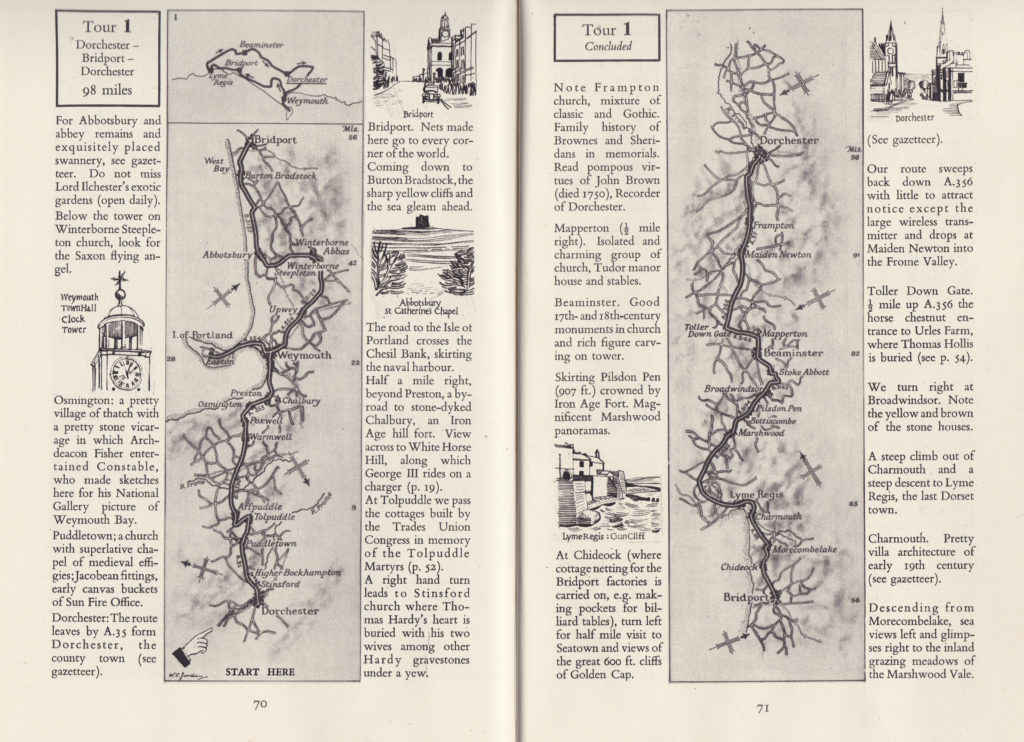

After the portrait of the region, the guide-book then provided a series of detailed tours to take the visitor through all the main features of the region. The tours used the strip map format first used by John Ogilby in the 17th century. Along the side of each map was a list of the main features of interest. For the Wessex region there were six tours which would give the visitor a comprehensive understanding of the region in question.

An example of one of the tours – tour 1 a circular route starting and ending at Bridport.

The guide-books concluded with the sentence “The Festival of Britain belongs to 1951. But we hope these explorers’ handbooks will be useful far beyond the Festival year”, which indeed they are, again to provide a snapshot of the country in 1951 and as the country was portrayed in line with the themes of the festival.

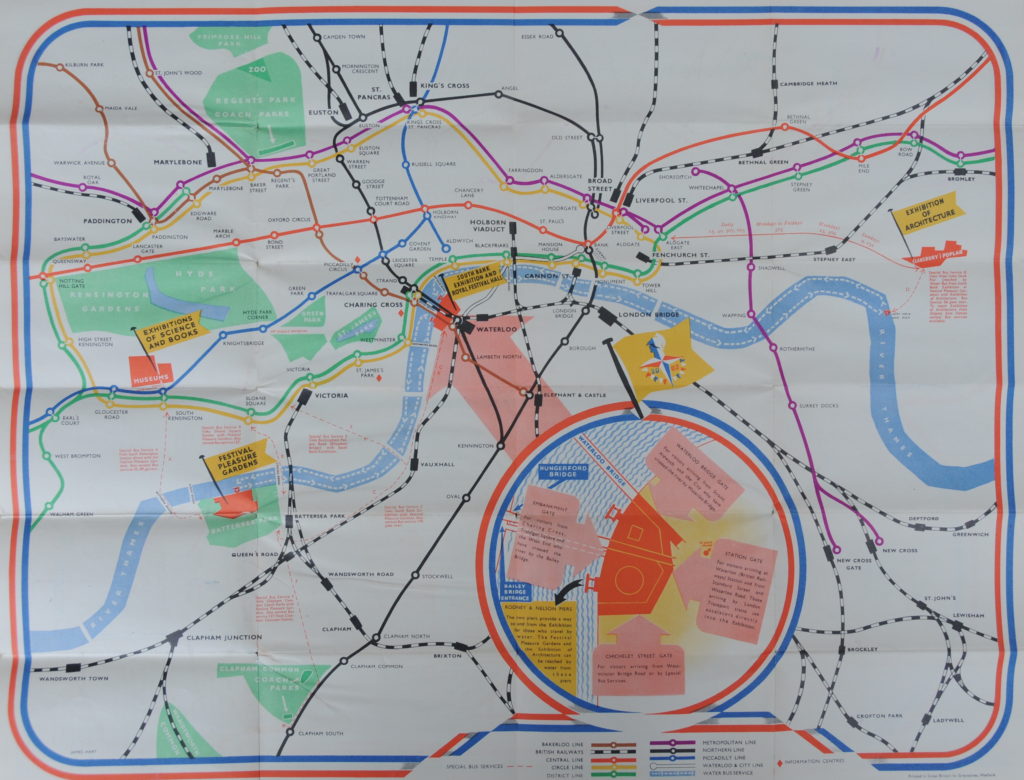

The News Chronicle (the paper of which Gerald Barry, the Director of the Festival had been the Editor) published a map, the Festival of Britain – Guide to London, which as well as showing the Festival of Britain locations, also showed other features of interest for the visitor to London. The map included pointers to areas outside the coverage of the map including Epping Forrest, Tottenham Hotspur and Arsenal Football Clubs, Greenwich, Hampton Court and Wembley.

The map also had the underground stations shown in their geographical positions rather than using the traditional underground map format. The map also shows a number of stations that have either changed name or closed since 1951 for example, Trafalgar Square Station.

The map is shown below. Again, it is a fascinating map with lots of detail from 1951. Click on the map to open a large scale version.

A special map for the Festival was also published by London Transport and British Railways which provided visitors to the festival with detailed guidance on how to reach the various festival sites across London. As well as English, the map included details in French and Spanish.

The cover of the map included the Abram Games festival symbol.

The transport map for the festival (again if you click on the map a larger version should open).

As well as the underground and overground rail routes, the map details the special bus services to the exhibitions of architecture, science and books as well as the Festival Pleasure Gardens.

The map also provides details of two events hosted by London Transport.

There was a London Transport Poster Exhibition in the subway at South Kensington Station where London Transport exhibited a display of past and present posters.

And in the ticket hall of Hyde Park Corner Station there was a London Area Art Exhibition displaying representative work from London area art schools.

In my posts so far on the festival, the tone of the festival has been educational and informative with a focus on the arts, science, design, architecture and industry, however a key aim of the festival was to involve as many people as possible in the festival summer and to use many different types of events to broaden interest and raise the profile of the Festival of Britain.

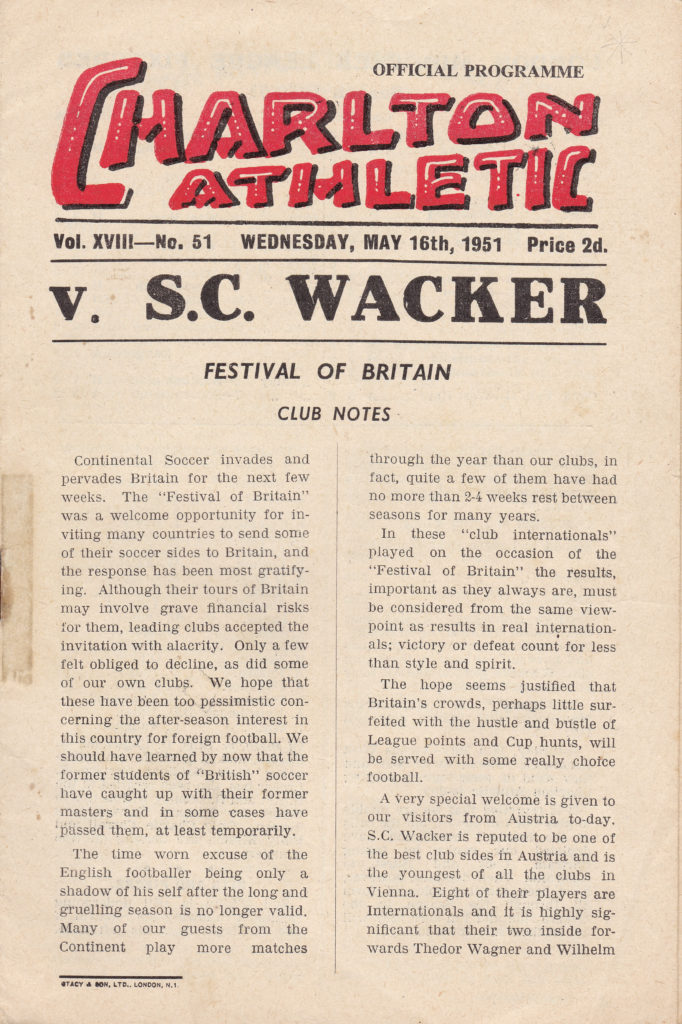

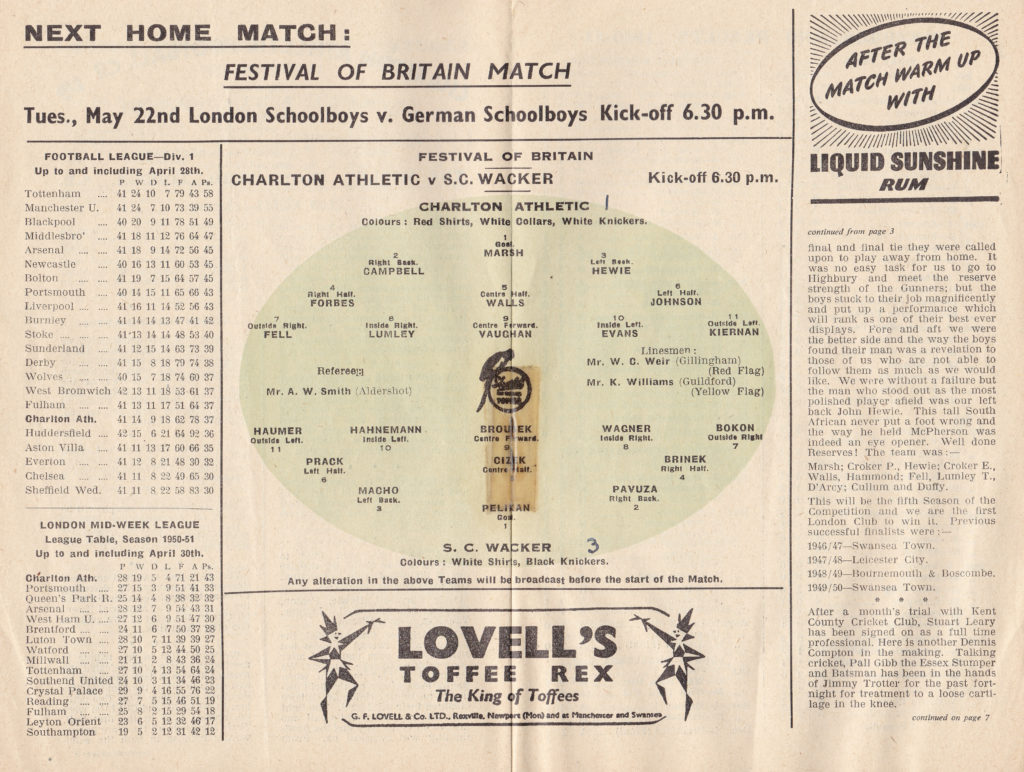

Sport was a route to reach sections of the population who may not normally attend an event such as the Festival of Britain, so to raise the profile of the festival and engage as much of the population as possible a range of sporting events were organised across football, rugby etc.

Games were organised under the banner of the Festival of Britain and outside of the normal league or cup games. A series of football matches were arranged between British and International clubs. This involved clubs from across Great Britain and a London example is the following game between Charlton Athletic and S.C. Wacker of Austria.

These games were organised after the end of the normal league season and involved international clubs touring the country in a series of “club internationals. Unfortunately for Charlton, they lost this game by 3 -1 to S.C. Wacker.

The centre of the programme provides a team listing, the state of League Division 1 (now the Premier League) and a notice that the next Festival of Britain match to be played at the Valley would be London Schoolboys v. German Schoolboys – I could not find the result of this match.

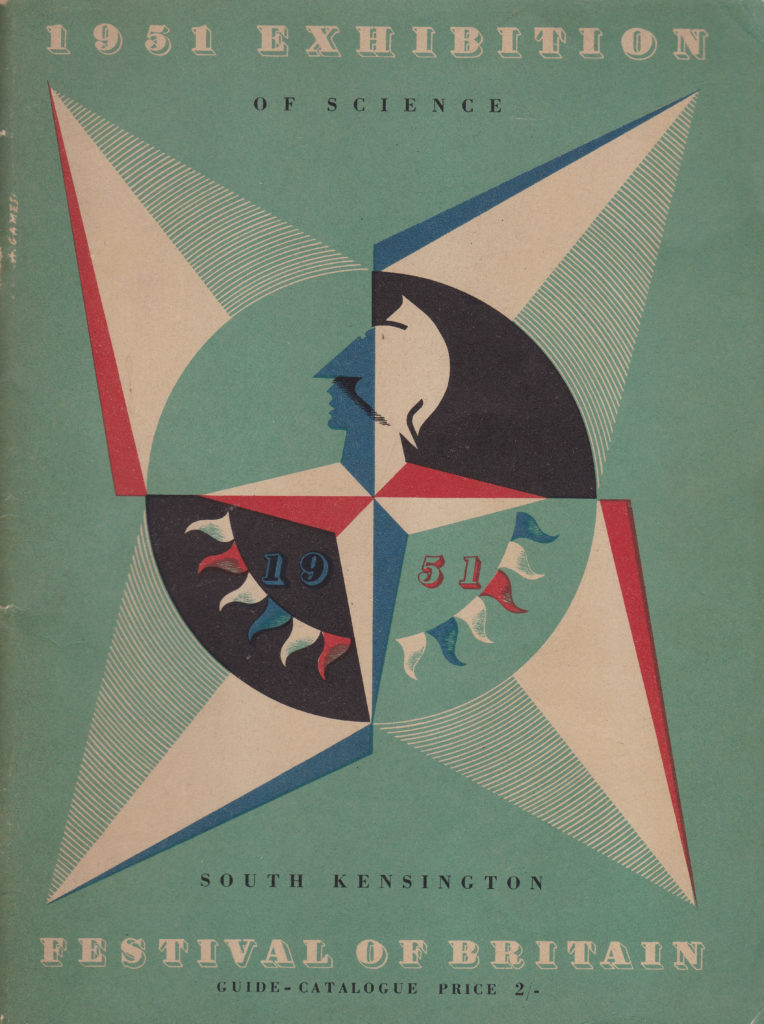

As well as Battersea and Poplar, the other main London exhibition outside of the South Bank was the Exhibition of Science held in South Kensington.

The Exhibition of Science was very factual and detailed, it was not, to use a current term, “dumbed down”. The exhibition assumed that the visitor wanted to, and could understand complex ideas if presented and explained clearly.

The exhibition guide was written by Dr. Jacob Bronowski who would later be responsible for the BBC series “The Ascent of Man” in 1973.

The exhibition was within part of the Science Museum buildings and featured the following exhibits:

- What matter Is

- Inside the atom

- Chemistry of life

- Chemical and Physical Structure

- Light, Rocks, Crystals, Metals, Colour

- Structure and Mechanism of Life

- What is Life?

- Cosmic Rays and the Universe

- Luminescence

- The Electronic Computer

The exhibition aimed to show that science is knowledge with a set of underlying ideas that can be understood and enjoyed by anyone.

The exhibition featured chemical formula, for example showing the chemical formula for Vitamin C, how it prevents scurvy and what happens to its effectiveness when the chemical structure is changed slightly. Technical names were used such as Para-Amino-Benzoic for the body chemical that feeds bacteria.

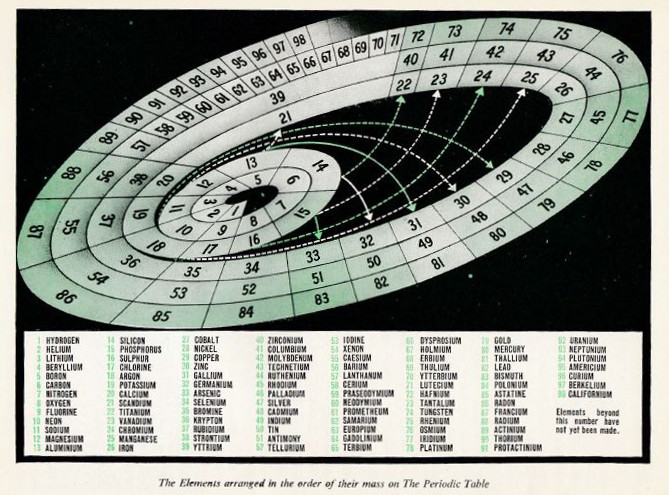

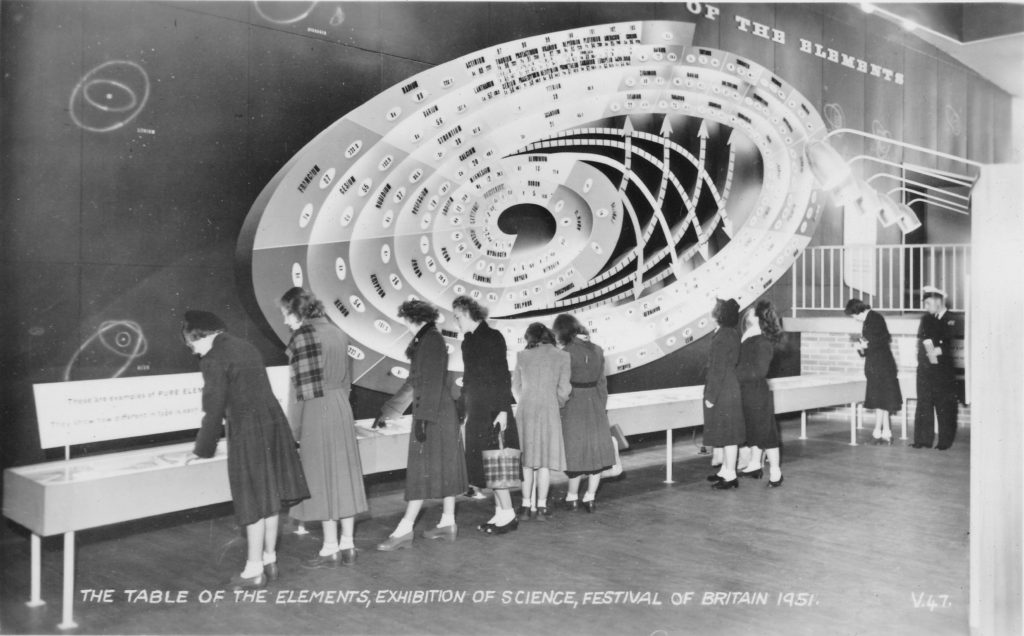

An example of one of the illustrations from the guide showing the periodic table:

The display in the Science Museum of the Periodic Table is shown in the following photo. I wish I had a colour copy as I suspect different colours were used to highlight different clusters of elements. The Festival of Britain used some very creative techniques to graphically display complex information.

The exhibition, along with the whole of the Festival of Britain was based on the premise that the British public had a thirst for knowledge and wanted to understand the world about them, and how the world would be changing in the future. The war had resulted in significant technical change and developments in nuclear energy, computing and materials would soon be making a major impact on the world.

Take for example the computer. Although early forms of computer had cracked German codes at Bletchly Park, this was still highly secret in 1951 and a very new concept and technology to the average person. One of the displays in the exhibition was on the Electronic Computer and the guidebook explains:

“No calculating machine is really a brain, because it does not think out its own instructions – it merely carries them out. But it can relieve the human brain of many mechanical tasks in calculations, and it can carry them out several thousand times faster than a human calculator. These tasks are not only addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. We can now construct a machine to solve long and difficult problems in algebra and calculus which require it to remember its answers to earlier problems, to choose between different answers and to use these to proceed by different methods. We can even make a machine to play NIM, because it is a mathematical game. Although it will not always win, the machine cannot make a mistake!”.

The exhibition also included a Chemical Laboratory and a Science Cinema with a programme of 40 minute films on a range of scientific topics being shown throughout the day.

Recognising the rapid developments in Science there was also a STOP PRESS section which highlighted recent achievements in science.

Jacob Bronowski summed up the exhibition and the part that British science has played in his closing paragraphs to the guide:

“The 1951 Exhibition of Science, South Kensington is part of the Festival of Britain. There is nothing fiercely British about this exhibition. Science is international, and the ideas and discoveries which are shown here belong to all mankind. Yet it is right to take pride that some of the greatest names in this exhibition are British: Newton and Darwin, Faraday and Rutherford and J.J. Thomson. Their work is our heritage: it is our ambition to continue it: but the greatest pride of each of us should be that we understand it.

The new work which you have just seen in the STOP PRESS is an inspiration, to remind us that in the last five years, Great Britain has won the Nobel Prize for physics three times, for chemistry once, and her three discoverers of penicillin have won the prize for medicine. And a British philosopher has won the prize for literature, and a pioneer in nutrition the Nobel Peace prize”.

As with all the guide books for the various festival exhibitions, the guide book to the Science Exhibition has a wealth of adverts for companies and industries associated with the theme of the exhibition. I featured adverts from the South Bank exhibition in an earlier post which you can find here.

The following are a sample from the Science Exhibition guide book. Reading through these adverts, it must have seemed at the time that British industry had an extremely bright future.

The industry failures, foreign take overs and loss of industrial capacity that would take place over the next few decades must have seemed unimaginable.

Sangamo Weston – the company behind the Weston light meter (I have one of these – see the post here). The company is still going, now renamed just Sangamo and based in Scotland, and I understand owned by the Schlumberger company of the US.

Imperial Smelting Corporation Ltd – once the operator of the largest zinc smelter in the world at Avonmouth. Went through a number of changes in ownership, becoming part of Rio Tinto Zinc in 1962 with the site closing in the 1970s.

EMI – mainly known as a record label and for the music industry, however EMI was also a very major player in the electronics industry and developed and produced a range of world leading products, including the worlds first CT Scanner. The electronics and research sides of the business were sold off over a number of years, for example the defense business went to Thales of France, the optoelectronics business went to Pilkington which was then also sold onto Thales.

The remaining music business went through different owners and is now a music label within the American-French Universal Music Group.

How different the future must have seemed in 1951 when EMI were advertising a secure future for technologists and offering training through EMI Institutes.

Leland Instruments Ltd – cannot find anything about this company.

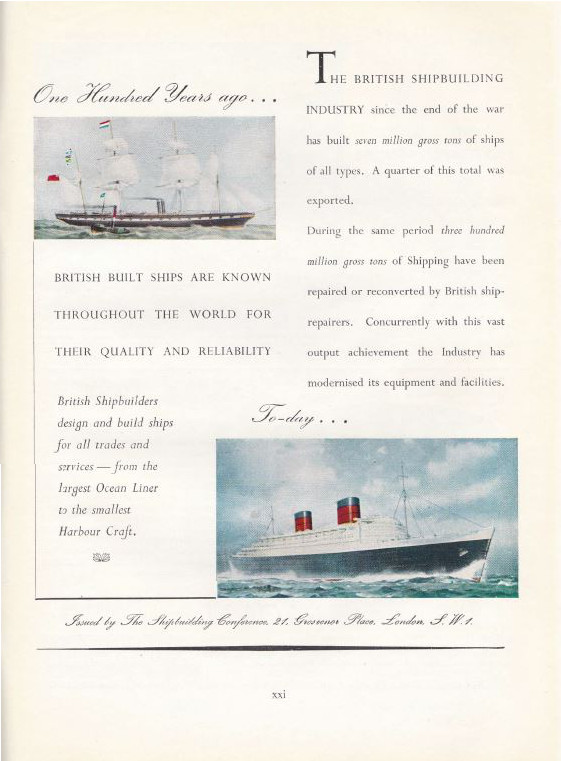

British Shipbuilders whose ships are known throughout the world for their quality and reliability – from the largest Ocean liner to the smallest harbour craft. Another industry that has reduced considerably with most Ocean liners now being built and serviced in France, Italy and Germany.

ICI – once one of the countries largest industries, was taken over by the Dutch firm AkzoNobel in 2007. See my post on ICI’s Millbank building here.

Abram Games

The designer of the Festival of Briton symbol, used on all festival literature, seen throughout the festival and across the country during the summer of 1951 was Abram Games.

Games was born in East London in 1914 and after attempts at formal art education at St. Martin’s School of Art, Games followed a path of being largely self taught and working freelance. Walking the London streets with a portfolio of poster designs looking for any work which was difficult considering his approach was very different to the current style of advertising and commercial posters and is now considered to have been many years ahead of its time.

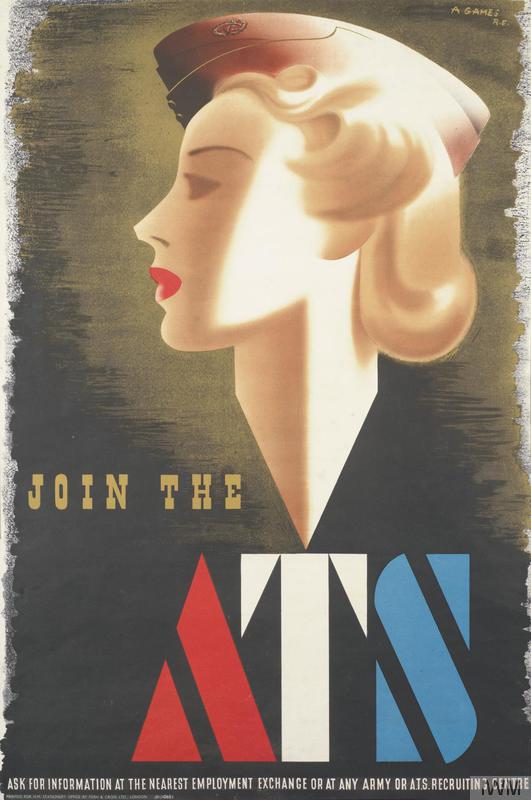

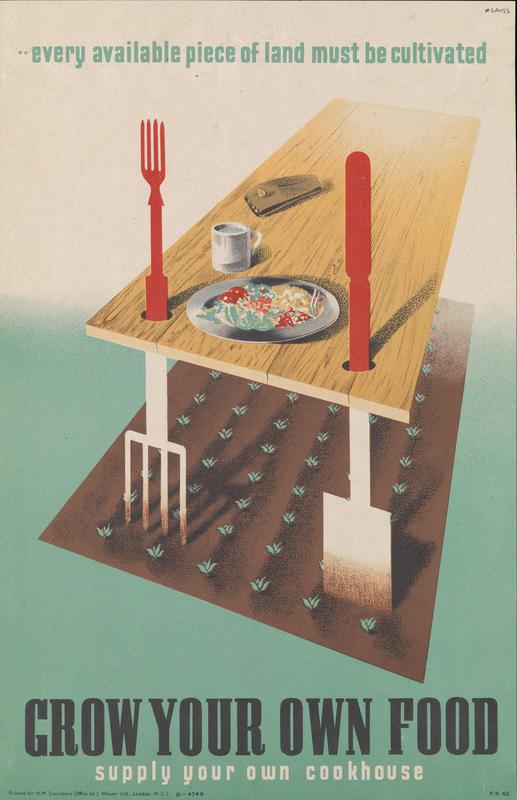

In 1940 Games joined the army as an infantry private. As during World War 1, posters were being used in the Second World War as a key format to inform and educate the public as well as recruitment into the many new roles required by a wartime economy.

Games watched the development of wartime posters and during a period of leave in 1940 went to see Jack Beddington at the Ministry of Information (Beddington had been a previous employer of Games’ freelance services when Beddington worked for Shell). Games offered his ideas on Army Poster Propaganda and later in 1941 was told to report to the War Office and became one of the few designers working on Army posters.

One of his first posters was for the Ministry of Information, for a recruitment poster for the Auxiliary Territorial Service (see the poster below). Although 10,000 were printed, they were later withdrawn after a debate in Parliament where it was argued that the poster was not the kind that would encourage mothers to send their girls into the Auxiliary Territorial Service.

Games continued poster design through the war and was overwhelmed by demands from so many wartime organisations. After the war he continued freelance work and lectured at the Royal College of Art.

In 1947 his first stamp design was issued for the 1948 Olympic Games and he then went on to win the competition for the 1951 Festival of Britain symbol, which brought Games to a much wider audience.

The symbol is simple, but very bold and clear. The figure of Britannia and the compass points with the coloured bunting and the year 1951 manage to convey in a simple design so much about the Festival of Britain. The symbol also had to work across a wide range of sizes and formats, from very small printed versions (for example on the maps and book cover shown in this post), it was used on flags and large versions where used across the festival sites.

The Festival of Britain symbol is a perfect example of Games’ approach to design:

Maximum Meaning

Minimum Means

Games continued to work on poster design as well as other mediums such as televison where he was commisioned to design for the BBC including the first animated identity for BBC television.

His work through the 1950s, 60, 70s and 80s included posters and designs for British Rail, Penguin Books, various national tourism authorities, British European Airways, Trade Exhibitions, The Times, London Transport – a very wide range of work but all with the same Games distinctive style.

Games was awarded the OBE in 1958 and appointed a Royal Designer for Industry in 1959.

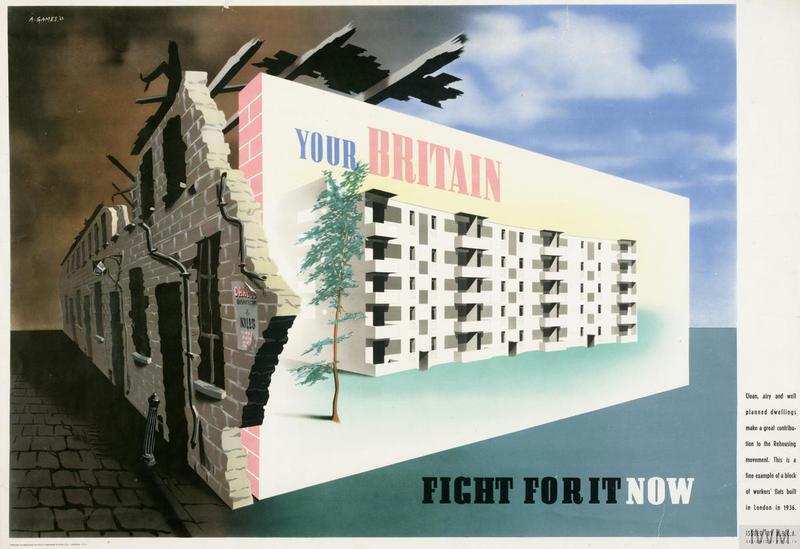

A sample of Games’ posters ( © IWM (Art.IWM PST 2832), IWM (Art.IWM PST 2891), IWM (Art.IWM PST 2909) and IWM (Art.IWM PST 2911) )

The posters above and below were two from a series of three published in 1942 titled “Your Britain – Fight For It Now”. The poster below shows the planned Finsbury Health Centre. The poster aimed to show that from the devastation of war a new future would be built, much better than the past, however when Churchill saw the poster he ordered that it be banned as the child with rickets in the background was considered a very negative image to portray in the middle of the war.

Abram Games died in August 1996, however his work continues to be some of the best work in graphic design, and the symbol he designed for the Festival of Britain must be one of the most recognisable symbols for an event, still easily associated with the festival 65 years later.

The symbol that Games designed for the festival can still be found across London and the rest of the country including a pub in Poplar which will be the subject of a future post.

In my final posts on the festival over the coming weeks, I will visit the Festival Pleasure Gardens at Battersea and the Exhibition of Architecture at Poplar.

At the age of 6, I attended the festival of Britain.

I only have snatched of memories of it. Yet it is something I will never completely forget. I remember particularly the huge ‘pole’ rising into the sky – the Skylon – I couldn’t understand what it was for. There were squirrels in the trees – models of squirrels – I wondered why they didn’t have real squirrels.

I remember being bewildered by the crowds and I remember an overhead cable car. Other than that, memory fades.

I have collected a lot of memorabilia throughout my life. Among it all is the Festival of Britain program. I also have a powder compact which my aunt bought at the exhibition. It has the logo on the lid.

I went to the Festival of Britain and it was a memorable experience for someone especially who had lived through the war years , as well as going to the Festival itself we saw much of London still showing all the dreadful damage still awaiting re-development. As well as that we got to go into the Dome of Discovery and saw the actual “largest piece of Plate Glass ever made at that time” My father worked on that and Pilkington Brother Glass manufacturers of St Helens, Lancashire had to have a special “low-loader vehicle” made to bring it down to London. We all lines the streets to see it go on its way.

I am too young to have attended the festival… but I remember seeing the emblem of the festival on the side of a panel of 11kilovolt switchgear in a substation called Griffin in Blackburn in the late 1970s. The local fokelore was that the whole of the switchboard (about 20 yards long) had been exhibited at the Festival prior to being commissioned in Blackburn. I don’t know if this is true or not, but it certainly had a number of emblems affixed to it. They were about 2 inches in diamter and blue and silver. When the switchboard was decomissioned in about 2005 I tried but failed to recover at least one of the emblems.

The switchboard was made by A Reyrolle and Co, of Hebburn. One of the most successful switchgear manufacturers in the UK for many decades.

Mike – that is fascinating. I knew that buildings had festival emblems when they had received an architectural award, but this is the first time I have heard about equipment having an emblem. The Festival of Power was in Glasgow so it may have come from there? A real shame you could not recover one of the emblems, that would have been a wonderful reminder of the Festival and the manufacturer.

I believe that Reyrolle went through a number of mergers and have ended up as part of Siemens – not sure if they are still manufacturing at Hebburn, or whether just a service centre for Siemens switchgear.

Excellent. Thanks for the introduction to Abram Games. I should have known about him, and now I do.

Also prescient today with the announcement of the almost certain sale of ARM Holdings to a Japanese interest is the reminder of the loss of EMI, ICI and other British commercial giants to foreign ownership.

Mike, thanks for the comment. I thought the same thing when I heard the news this morning regarding ARM. The adverts in the guide books for the various Festival of Britain events read like a roll call of industries and companies lost over the last 60 years. Just shows how a view of the future can turn out very differently. Good thing about history is that is also offers an interesting perspective on what the future may hold.

Thank you for yet another fascinating entry. You never fail to impress and inform. You might like to know, with regard to your future entry on the Festival Gardens at Battersea, the Royal Institute of British Architects has recently acquired the archive of Harrison & Seel relating to the Gardens. They were the executant architects in overall control of the project and their files contain a huge number of photographs of the site before, during construction and after opening. Like the main Festival site on the South Bank, it was all done on a shoe string and in a very short time , probably impossible today.

Charles, thanks for the information and for your comments on my posts. I did not know that RIBA has the archives of Harrison and Seel. I hope to publish the post on Battersea this Sunday but will try and have a look at these archives at a later date and update the post. Agree it was done on a shoe string, but unlike all the other festival locations, the Festival Gardens allowed sponsorship which must have helped.It was impressive how much was achieved in such a short time. There were several festival sites, it was not that long after the war with many other demands on manpower and materials and the country was short of money. That is one of the aspects of the festival that fascinates me – the vision and effort of so many talented people to deliver such a positive view of the future.

Such a contrast with the Millennium projects! The H & S photographs should be catalogued soon and available at the RIBA’s HQ in Portland Place. The associated drawings are at the RIBA’s Study Room at the V&A. It’s often worth having a look at our online catalogue (www.architecture.com) as we have huge London collections. Keep up the good work. I really look forward to your posts

can any one tell me about the daily telegraph festival of britain map of london

No such thing!!!

Now part of our living heritage my FoB blog

https://modernmooch.com/2017/08/29/pleasure-gardens-battersea/

I have been sorting through some jigsaws that we inherited from my mother in law and ‘What do they talk about’ is one of them! It is beautifully and intricately cut from plywood and I’m sure that it must be contemporary with the printed map. I wonder if the map was originally with the jigsaw? Need less to say, the jigsaw is unboxed and came with no picture so it was a lovely surprise to see what it was!

Fabulous amount of detail.

I have written a chapter about a Scottish songbook published for Festival of Britain year. Contributed to a book which should come out later this year, if you’re interested. Afraid I don’t know exactly when!