Towards the end of the last war, a whole series of reports were commissioned into the rebuilding and development of the City of London. These reports used the opportunity for major reconstruction to propose significant change and to address the needs that the City would be expected to support in the future.

I have already written about a number of these reports, including the 1944 report on Post War Construction in the City of London, the 1943 County of London Plan and the 1944 Railway (London Plan) Committee report. For this week’s post I would like to cover another report, covered in a book that documented proposed redevelopment of the City of London.

This was published in 1951 by the Architectural press, on behalf of the Corporation of London as the City of London – a record of Destruction and Survival, with a report on reconstruction by the planning consultants C.H. Holden and W.G. Holford.

The preface to the book provides some background “In April 1947 the joint consultants on Reconstruction in the City of London, Dr. C.H. Holden and Professor W.G. Holford, presented their final report to the Improvements and Town Planning Committee of the Corporation. The proposals contained in that report were subsequently accepted in principle by the Court of Common Council, and the Court approved the publication of a book to describe and illustrate the proposals for rebuilding more fully than had been possible up to that time. In the preparation of such a volume the opportunity has also been taken to record the damage suffered by the City from aerial attack during the war of 1939-45.”

The 1951 book is far more comprehensive than the earlier reports. It includes a detailed historical background to the City of London, including a chronological table and describes in detail the war damaged areas. There are numerous statistical details and plenty of maps overlaid with detail on the pre-war City and future plans for the City.

Reading the book in 2019 also demonstrates the difficulty in making long term plans. Unforeseen events frequently resulted in an expected future trend becoming obsolete.

The book includes many proposals that we can see around the City today, some looking remarkably modern for their time. Other proposals, thankfully, did not get implemented as they would have left a significant architectural and visual scar on the City.

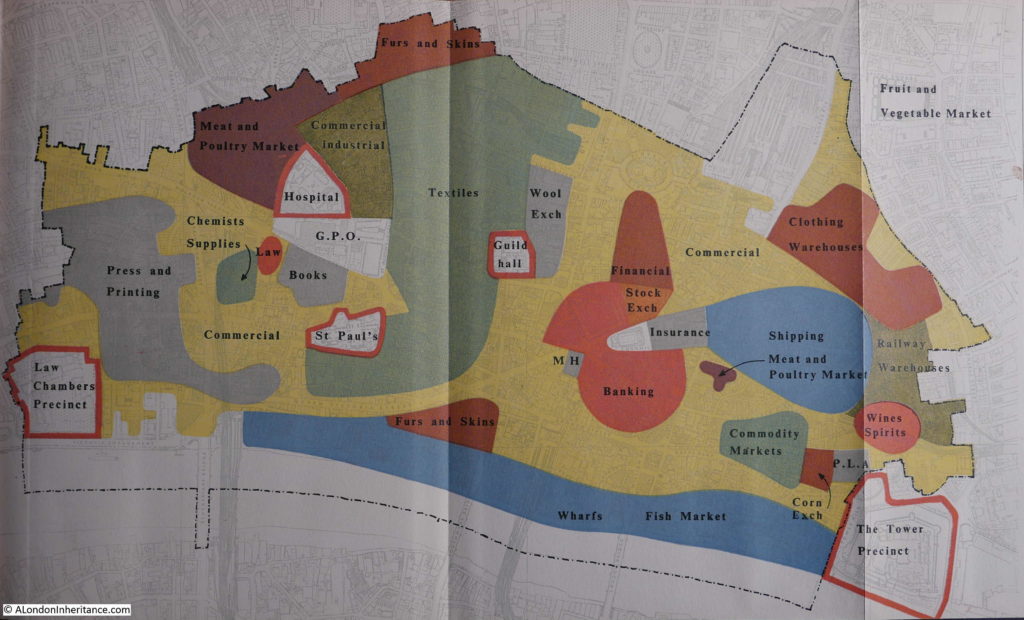

One of the first maps aims to provide a view of the main functions of the City and how these are grouped into specific geographical areas. The following map is titled “Distribution Of Trades And Activities, 1938” (if you click on the maps you should be able to open up a larger version)

Yellow is General Commercial and takes up large parts of the City. The area along the river is still dominated by Wharfs and the Billingsgate Fish Market. Textiles take up the area from around St. Paul’s Cathedral and up to the north of the City. The Press and Printing surrounds Fleet Street. There are smaller concentrations of specialist trades – Chemists Supplies, Books, Wines & Spirits. Railway Warehouses and Clothing Warehouses occupy the east of the City.

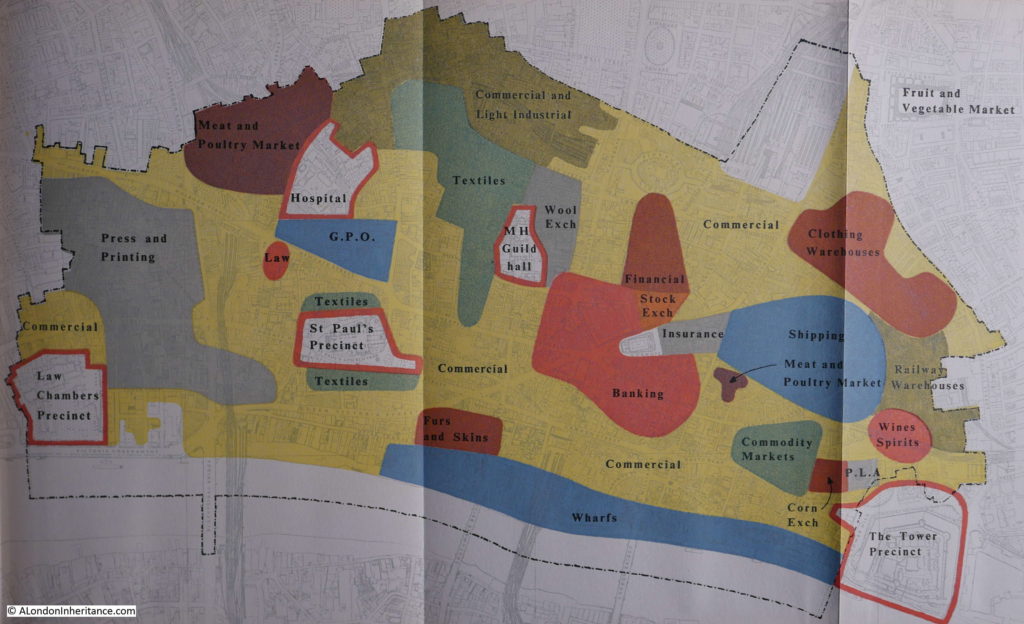

The book tries to look at how these trades should be distributed in the future City. The following map is titled “Proposed Distribution of Trades and Activities”

At first glance the map is much the same as pre-war, however there are some subtle differences. Wharfs still occupy the river bank, but the fish market has moved. Chemist Supplies has disappeared from the City. In the north of the City a much larger area has now been allocated to Commercial and Light Industrial, reducing the area for Textiles, Furs & Skins – the expectation was that new Light Industrial businesses would start to replace some of the traditional City trades.

Apart from these relatively small changes, the immediate post war planning expected the trades that would occupy the City would continue to be much the same. Cargo ships and Lighters would still moor along the wharfs, textiles would occupy a large part of the City as would the Press and Printing. The following 30 to 40 years would transform the trades and activities of the City far beyond the expectations of 1951.

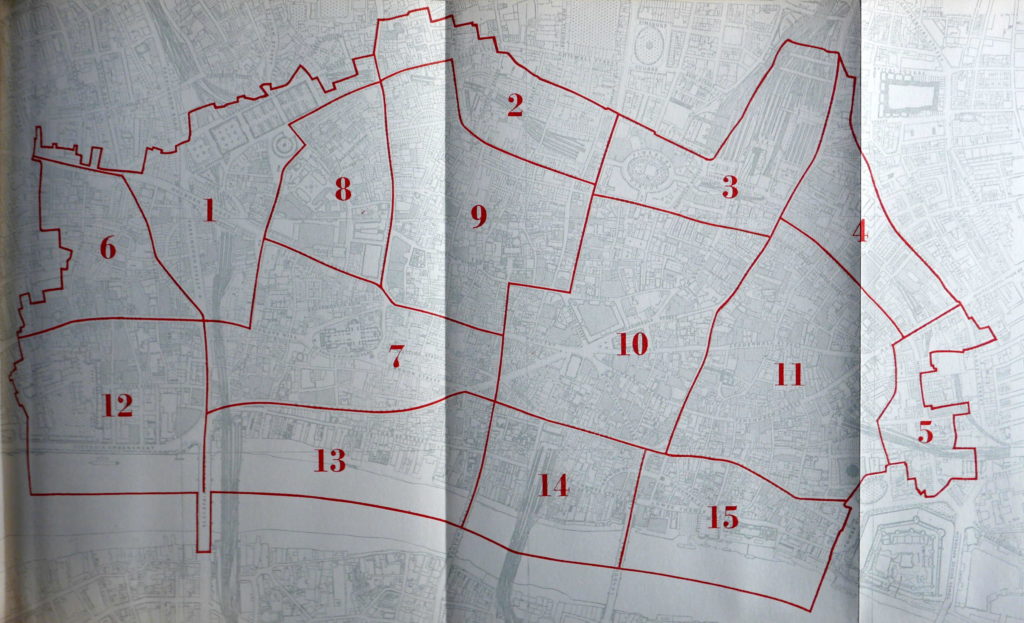

Another map looked at the Inventory of Accommodation within the City.

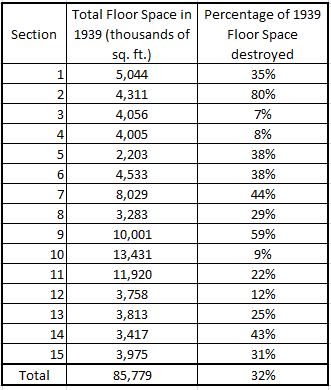

The map details the total floor space in 1939 for each area along with the percentage of floor space destroyed during the war. These figures are shown in the following table:

By comparison, the latest City of London Housing Stock Report (December 2018), does not report on the amount of accommodation floor space, rather the number of residential units in the City of London (7,240) along with the split of these residential units by the number of habitable rooms.

The map also highlights the considerable amount of damage caused by the early raids of 1940 / 41 when incendiaries caused significant fire damage in the areas around and to the north of St. Paul’s Cathedral as shown by the high percentage figures for blocks 2,7 and 9.

A key focus of the report was the support of pedestrian and vehicle traffic throughout the City. New boundary routes were proposed to the north and south of the City to support traffic passing through the City to get between east and west London and across the river. Plans also included widening of streets, new streets driving across existing street and buildings and elevated sections for roads.

High and low level separation of pedestrians and vehicles was seen as the way forward for the City. Two main areas where this would apply would be the northern boundary route along Holborn to Aldersgate and the south route along Thames Street.

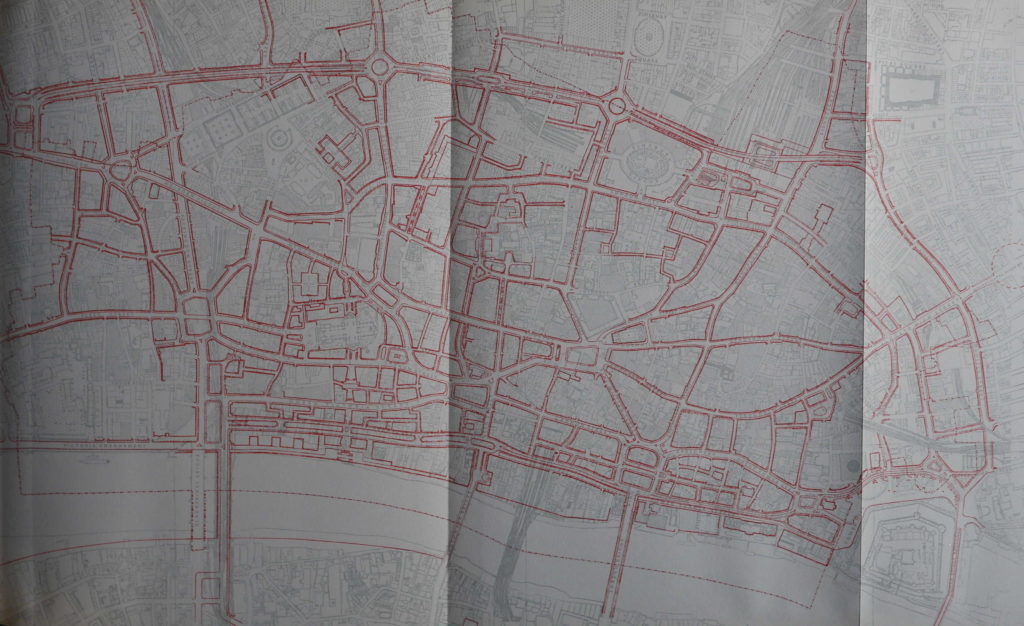

The following map shows where improvements or changes would be made, marked by the streets in red.

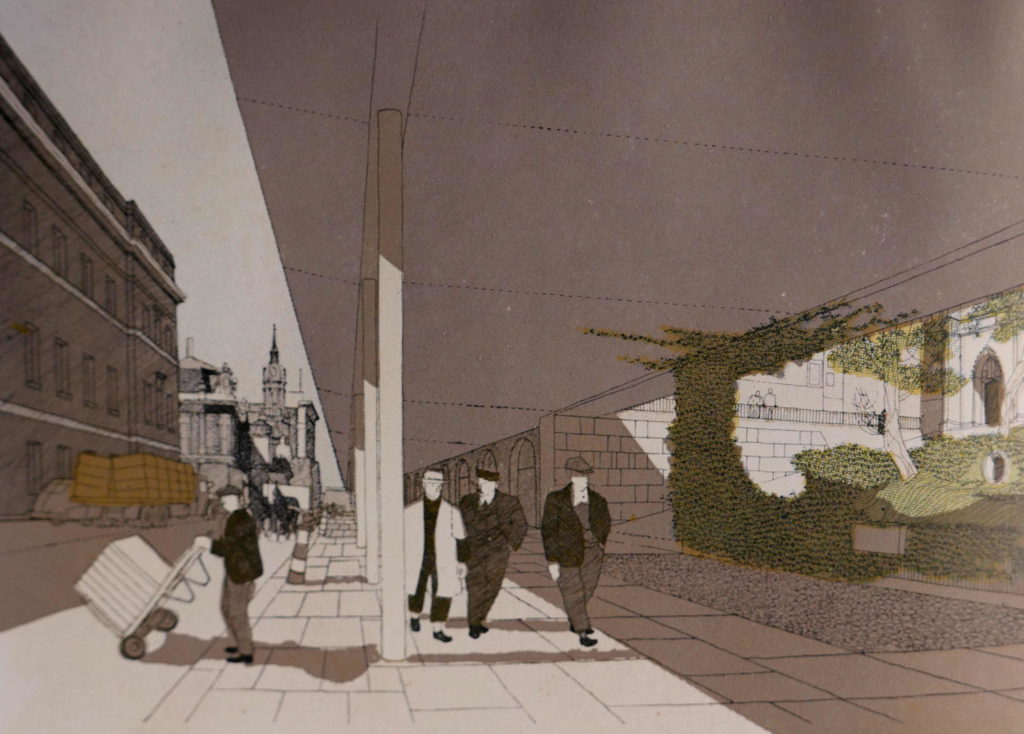

The book includes many artist impressions of what the proposed developments would look like. The following drawing show the proposed high level road in Lower Thames Street, with ground level occupied with a service road and pedestrian area.

The proposal for Lower Thames Street is very different to what was finally implemented, with a multi-lane road built at ground level by widening the original street. The level of traffic does not lead to a pleasant experience walking along the street today, and the artist impression above does look good, but the impact of a high level road would have destroyed the whole view of the street and I suspect would not have been wide enough to support the growth in the level of City traffic.

The book also goes into detail on the public utility services needed to support a city and aspects of street furniture which were all considered as part of the overall designs needed for improving the City’s streets for pedestrians and drivers.

In describing how these utility services and street furniture would be implemented, the book includes the historical context, and as an example, the following illustration from the book shows the development of lamp standards from 1827 to 1946.

Continuing on the theme of pedestrianised areas, the book describes a number of options, supported by artist impressions for how traffic and pedestrians would be separated and large areas opened up for pedestrian circulation.

The following drawing is of the proposed low level concourse at London Bridgehead, just to the west of the Monument.

Although from a book published in 1950, I find these impressions of a redeveloped London curiously modern. Change the name on the glass fronted Tea Rooms on the right to a Starbucks or Pret, change the Sherry sign on the left to Gin and update the clothes the people are wearing and this could be a proposal for today.

The following impression, also of the proposed London Bridgehead is again (apart from the clothes) rather modern.

In many of these artist impressions there are cafes and restaurants shown lining the edge of the pedestrian areas. The proposals within the book see these as meeting a key need for City workers as “The City is chronically short of places to have lunch”. I suspect the authors would be rather pleased with the number of establishments in the City today to provide a worker’s lunch.

There are other ways in which the 1951 artists impressions are surprisingly modern. The following artist impression is described as “A view of the base of the Monument and the proposed new Underground entrance as they would be seen from Monument Street, if the two level proposal were carried out.”

The high level separation of traffic can be seen as part of the large circulatory road system on the northern end of London Bridge.

To the right is a glass sided entrance to the Monument Underground Station with the London Transport roundel on the side. This would have replaced the entrance on Fish Street Hill which today is an entrance directly on the ground floor of an office building rather than this rather nice, glass sided descent by escalator.

This type of entrance has been used at a number of Underground stations, one of the latest being a couple of entrances to the Tottenham Court Road Underground station. I was passing in the week and took the following photo – perhaps not so elegant as the 1951 plans, but such is the way of all artist impressions.

Proposals for developments along the river’s edge included terraced walkways along the river, with entrances between the warehouses opening up views to the river. The following drawing illustrates the proposals, but also shows how the proposals were not aware of the future changes to the use of the river, with shipping and cranes still expected to line the river.

I love the artistic addition of the two men in some form of naval officers uniform.

The book describes these river side developments “The first buildings to be rebuilt near Upper Thames Street are likely to adjoin the high level road, and where stairs lead down to the low level some look-out points might be arranged from which the river can be seen between the warehouses below. Another possibility is the building of restaurants or public houses right on the river front.”

Another drawing shows that “the Consultants propose a riverside walk along the river front below Upper Thames Street. The drawing shows how a maritime atmosphere might be introduced here.”

The proposals were very enthusiastic about the opportunities of opening up the river front, an area that for centuries had been hidden behind the warehouses, wharfs and fish market that traditionally lined the river. The book describes “Another possible form for new buildings on the river front is that they should be warehouses below and offices above, the offices set back to provide a pedestrian walk overlooking the river – perhaps one with a distinctly maritime atmosphere. A riverside pedestrian walk from Blackfriars to St. Paul’s Steps or even to Southwark Bridge would be one of the sights of London; and one of the best viewpoints in London, as it would command the river from Whitehall to the Pool – not forgetting the new South Bank. A walk over the top of warehouses that handle riverborne goods would be difficult to design. Pedestrians might damage goods in lighters below and a carelessly handled crane might damage pedestrians. Yet these and many other difficulties – real though they are – seem small in comparison with the possibilities of such a walk planned along the now largely outworn strip of buildings from Blackfriars to Southwark bridge. It is a wonderful site.”

It is indeed a wonderful site and a riverside walk has been realised for parts of the route, although at a single riverside level rather than the multi-layer possibilities of the 1951 proposals. No longer any risk that a “carelessly handled crane might damage pedestrians.”

The comments about the riverborne goods, issues with cranes etc. also show the difficulties with long term planning as those working on the 1951 plan were unaware of the changes that would take place to river traffic in the next few decades with not only the loss of all goods traffic, cranes and warehouses in the Pool of London, but also further down the river at the much larger docks. Who would be a city planner ?

In improving the experience for pedestrians, the proposals including opening up views to the river as mentioned above. Another key view was that of St. Paul’s Cathedral to and from the river.

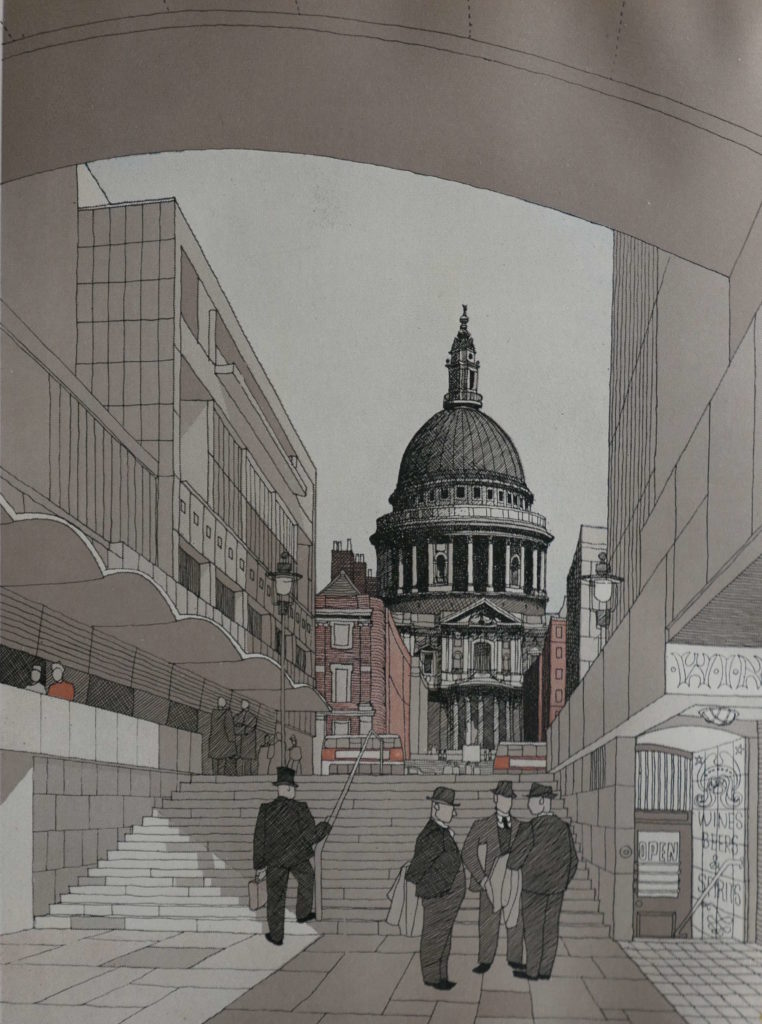

The following drawing is titled “An impression of a possible treatment of the proposed new approach to St. Paul’s from the river.”

The development of this area has resulted in a view that is broadly similar to that proposed in the 1951 plan, although the buildings along the side are different and I suspect the width of the pedestrian walkway is today wider than the impression given in the drawing.

The proposals so far, would have had a positive impact on the City, however other proposals, whilst for very good reasons would have been very negative and I am thankful that they were never built.

Post war, continuation of pre-war growth in vehicle traffic was expected and proposals were included in the 1951 book to manage an increasing growth in motor traffic.

New through routes were planned for the south of the City along Lower and Upper Thames Street and a northern boundary route was proposed, cutting through numerous streets north of Smithfield and Finsbury Circus (see the map above with the red street highlighting).

The book included artist impressions of what these developments could look like and they are frankly horrendous.

The following drawing is titled “The raised Northern Boundary Route proposed by the consultants, would have two decks of car parking space under it.”

Thankfully this was never built along the northern edge of the City and as its name implies, the Northern Boundary Route, would have indeed formed a solid boundary between the City and the land to the north.

It was not just the boundary routes where major changes were proposed to accommodate traffic, the central City also had some horrendous schemes.

The following drawing is titled “An impression of the suggested Cheapside Underpass, a proposal which, has been postponed on grounds of cost.”

Yes, that is the church of St. Mary-le-Bow to the right, with Cheapside dug out to form a lower level for traffic. Thankfully it was postponed on grounds of cost and never resurrected.

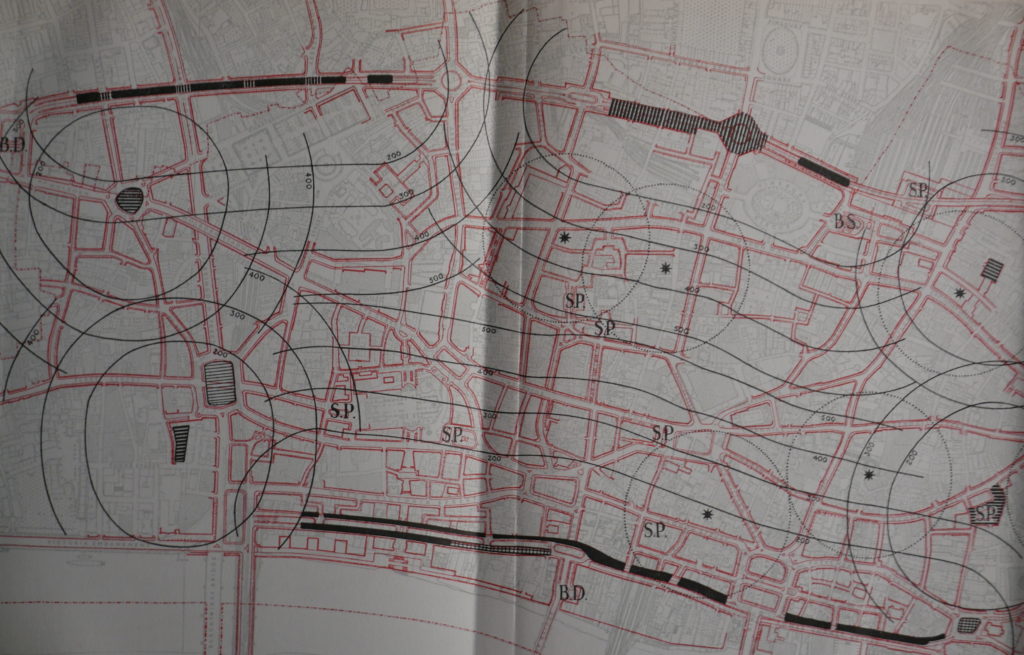

If the proposals had been fully implemented, there would have been considerable infrastructure across the City to support the car. The following map shows proposed Car Parks and Garages.

Solid black shows where multi-level car parks were proposed. The run of car parks at top left were those shown in the drawing of the northern boundary route above. Note also that multi-level car parks would have run along Upper and Lower Thames Street.

The tick vertical lines represent underground car parking. Horizontal lines represent additional possible car parking whilst the limited number of cross hatch markings represent possible lorry parks.

The star symbols represent locations for commercial multi-storey garages.

There would not have been a problem parking in the City of London if all this lot had been built.

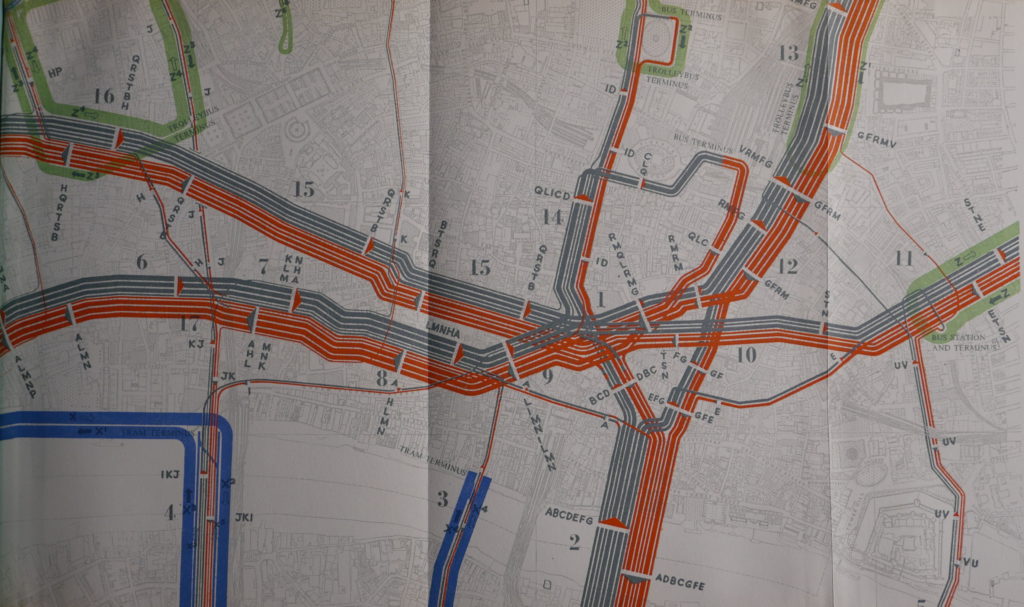

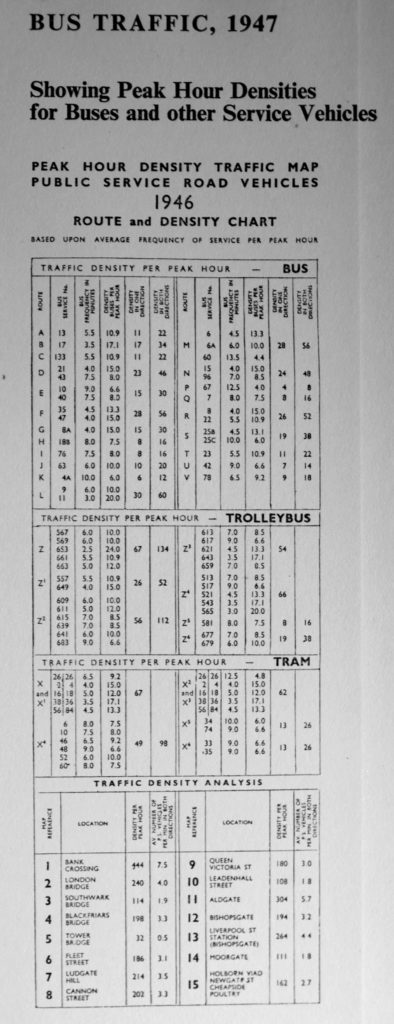

Although there was considerable emphasis on the car and other forms of motor traffic, public transport was also a consideration. The following diagram shows Bus Traffic in 1947.

The table that accompanies the above diagram is shown below. This details the traffic density during the peak hour for the bus routes through the City and includes bus service number, frequency, density of buses per peak hour, and density in either direction. As a reminder that buses were not the only form of ground level public transport at the time, similar data is also provided for trolleybus and trams.

Given the time, I would love to create similar tables for bus traffic today as a comparison.

The title of the book includes the sub-title “A Record Of Destruction And Survival”. The book has a large section documenting the destruction of parts of the City during the war. This part of the book includes a large number of photos. It was fascinating to find that a number of these photos were of similar scenes to the photos taken by my father.

The following is my father’s photo of the tower of All Hallows Staining taken from Mark Lane.

This photo from the book also shows the tower of All Hallows Staining, but from the opposite side, looking back towards Fenchurch Street Station, the facade of which can be seen in the rear of the photo.

Another of my father’s photos showed a very large pile of rubble following the demolition of bombed buildings in Aldersgate.

The book also includes a similar photo with the title “A mountain of rubble from bombed buildings piled up on a derelict site off Aldersgate Street.”

The City of London – a record of Destruction and Survival is a fascinating book. Although primarily a means of publishing the 1947 proposals, in its 340 pages the book contains a wealth of information on the history of the City, the damage to the City during the war, the workings of the City, the start of redevelopment of the City and what the City could look like should the proposals be fully implemented. The text and photos are supported with lots of data and statistics.

And for me, a book with fold out maps is always a thing of beauty.

The immediate post war period created many proposals that if fully implemented would have transformed the City of London. Thankfully the multi-level traffic routes did not get built, Cheapside did not get an underpass and the north and south of the City are not bounded by multi-storey car parks.

The ideas about creating space for pedestrians are good, as are the proposals for opening up the views of the river and walkways along the river. Many of these ideas have been implemented, but perhaps not as dramatically as proposed in 1951.

The separation of pedestrians and traffic can still be seen in the remaining lengths of the pedestrian ways (pedways).

When reading these books, I always wonder what the authors of these proposals would think of the City if they could take a look today, 70 years later. Would they be pleased with the result, would they wonder about the lost opportunities, and perhaps be thankful that some of their proposals were not implemented.

Planning the development of a City for the long term is very difficult, there is no way of knowing what external or internal changes may suddenly move the City in a new direction. It is intriguing to wonder what the City of London will look like in another 70 years.

Thank you for this (as always) fascinating post. I had forgotten I had a copy of this book (albeit without the rare dustwrapper) and have found it on my shelves. It is a truly remarkable book, packed with superb illustrations (photographs & drawings) plus maps and historical information. Perfect to settle in the armchair by the fair on a cold, grey, windy afternoon! Thank you.

“Reading the book in 2019 also demonstrates the difficulty in making long term plans. Unforeseen events frequently resulted in an expected future trend becoming obsolete.”

That’s a generous understatement! I’d substitute “usually” for “frequently.” Thanks again for posts such as these. When wandering about the City I’m regularly thankful that central planning has had relatively minimal (and inevitably deleterious) long-term effects on the place compared with, say, Paris. Perhaps the best thing ever to happen to London was that Wren’s master plan wasn’t realized as, say, Haussmann’s was in Paris.

So lovely still to enjoy the City’s medieval alleys and the regular, spontaneous regeneration of the City, which makes it a living, organic place compared with Paris’ inner-ring museum-like sterility. Layers of history and vibrant present-day enterprise atop it all. Thank goodness. (And thank goodness that most of the post-war monstrosities have been demolished and the bitter fruits of clumsy master-planning have withered away.)

Finally, thanks for the old photos of All Hallows Staining. I was in London last month for the first time in a year and made a point to venture down Star Alley per one of your posts. I enjoyed the alley, the church tower, and the obstructed view of the facade of Fenchurch Station, among other features in the area that you’d noted. I often try to imagine what the place looked like in the late ’40s with so much rubble about. and uninterrupted vistas in certain areas.

As usual very interesting reading ,well done sir.

Fascinating, 1947, the year I was.born. I remember going to the cinema in the late 50s and so admired everything American. I am so grateful that much of this was not implemented.

I have to say that the developers still seem to be seeking out any tiny piece of historic London that they destroy.

Your father’s and your photos are a treasure, thank you

Another very interesting piece. What is sad is the presumption that the planners had to accommodate all the private traffic that wished to access the City. There was no presumption to limit access. It reached the peak of absurdity when a plan was published for three concentric motorways – the M25, one following the North and South Circulars and one even further into London. They even started building some of the innermost one as witnessed by the monstrosity of Westway elevated above the surrounding houses, shops etc between Paddington and North Kensington. I think it was the appalling consequences and the huge costs of that development that started to change opinions. But it has taken a long time to remove traffic from narrow streets, to introduce congestion charging and invest in public transport. I’m not sure enough is yet being done. But thank goodness that much of those plans didn’t get enacted.

I walked the route from the Millenium Bridge to St Paul’s last week and it is definitely wider than shown here.

love the book, full of the future and a peaceful place to be after ww2 and the destruction caused to my home town. BUT why did the developers think it fit to move me and 3 generations of my family out of the area? where we not part of the fabric of the City? did not my family work hard to protect the City? build and labour for it? in 1880 the first members of my family on both sides, moved into Viaduct buildings Saffron Hill.

and there we stayed until the mid 1950s when we where false to leave under the heading “slum clearance” and none of us ever settled again. even now, I feel like a refugee trying to find my way back home. the City is deep rooted in me. and as for viaduct buildings, they still stand, mainly empty, as a grade listed 2 building being the first social housing built by the corporation.