I have been on the majority of the London Transport Museum’s Hidden London tours, but until a couple of weeks ago had not been on the tour of 55 Broadway. Built in 1929 as the head office of the Underground Group, 55 Broadway continues to serve this role through the descendants of the original company, London Transport and Transport for London.

55 Broadway is reached from Westminster by walking up Tothill Street to where Broadway divides past the building, which is also above St. James’s Park underground station. Despite being almost 90 years old, 55 Broadway is still a very impressive building.

In the first decades of the 20th century, the London Underground was expanding rapidly and the company needed a headquarters building that suited a forward looking and innovative company. The architecturally overly decorative and fussy buildings of the 19th and early 20th centuries did not meet the aspirations of those running the Underground Company, the Chairman of the Board, Lord Ashfield and Frank Pick the Managing Director (although these aspirations did not include moving away from the hierarchical structure of the company as will be seen when touring the building).

The modernist architect Charles Holden had already worked with the Underground Company and was commissioned to work with Ashfield and Pick on the design for 55 Broadway.

The site for the new building was a rather complex shape and had to accommodate the underground station and the station entrance at ground level.

Holden designed the main building in the shape of a crucifix with the longest wing leading back from where Broadway met Tothiil Street to provide the imposing view seen above when walking from Westminster.

The crucifix shape of the building also makes best use of natural light within the building with all the offices being close to large windows, made possible as the external walls are not load bearing as the building uses a structural steel frame for support.

Just above the main entrance facing Tothil Street is the name of the building, the station and between these is the Royal Institute of British Architects, London Architecture Medal for 1929, the year the building was completed.

In the following photo from the Britain from Above website, 55 Broadway can be seen slightly above and right the centre of the photo. The crucifix shape of the building is clear in an aerial view. The photo is from 1928 and whilst the main body of the building is complete, the steel frame for the central tower shows that this part was still awaiting completion.

The large windows can be clearly seen in this view looking towards the centre of the building with two of the wings of the crucifix shape and the central tower. Note also just over half way up, the buttress between the two wings to provide additional structural strength by tying these two wings together.

Although the building was intended to be of a modernist design and not to be covered with the decorative features so common in buildings of the previous century, Holden and Pick did want the building to create a visual impact and therefore commissioned a number of modernist sculptors to provide a small number of sculptures for the building which would complement rather than overwhelm the design of the building.

On the two main sides of the building are statues by Jacob Epstein. These were highly controversial at the time and divided opinion among the public and art critics.

The statue in the photo below was the first of the pair to be finished and is titled “Night”.

The following extract from the Illustrated London News on the 1st June 1929 is typical of newspaper reporting of the statues:

“THE MUCH-DISCUSSED EPSTEIN STATUARY ON A NEW LONDON BUILDING; ‘NIGHT’ – A GROUP WHICH THE SCULPTOR HIMSELF DESCRIBES AS ‘AN EMBODIMENT OF THOUGHT IN PLASTIC FORM’. Mr Jacob Epstein has again provided London with a public work in sculpture that has aroused a storm of aesthetic controversy. ‘Night’ is the first finished of the two companion groups (the other being ‘Day’) executed for the new Underground Railways Building over St. James’s Park Station. It is about 9ft high, and represents a mother (called by the sculptor a ‘Madonna’) soothing a child to sleep. While some critics hail it as his finest work, others denounce it as repellent, formless, and distorted. Mr Epstein himself is reported to have said: ‘Sculpture can only live as long as it is the embodiment of thought in plastic form….I do not distort the human form more than is necessary to force my main idea. All the greatest sculptors of the world have modified nature to suit the purpose of the subject – Michelangelo especially. The sculptor must understand anatomy from A to Z; but he is not a surgeon – he is an artist.”

The unveiling of “Day” continued the controversy with campaigns for the two statues to be removed, however Epstein robustly defended his work. In a newspaper article titled “Epstein Defends His Night” he wrote:

“If the man in the street does not like the look of my ‘Night’ on his daily way to work he can always avert his eyes from it. In any case the artist who considers that the taste of the masses is a goal is stultifying his own art. Why ask the opinion of the man in the street at all? One does not ask this man in the street his opinion of good music, one goes to hear it oneself, and forms an opinion of the work on its own merits. So why ask him about sculpture?”.

Epstein’s work did seem to generate very divided and strong opinions, one of his works in Hyde Park was tarred and feathered soon after installation.

As a compromise to let the Night and Day statues remain, Epstein did remove 1.5 inches from his statue “Day” shown below:

In addition to these two main features, there were other sculptures with the theme of the four winds.

West Wind by Henry Moore:

South Wind by Eric Gill:

North Wind by Eric Gill:

West Wind by Samuel Rabinovitch:

North Wind by Alfred Gerrard:

East Wind by Allan Wyon:

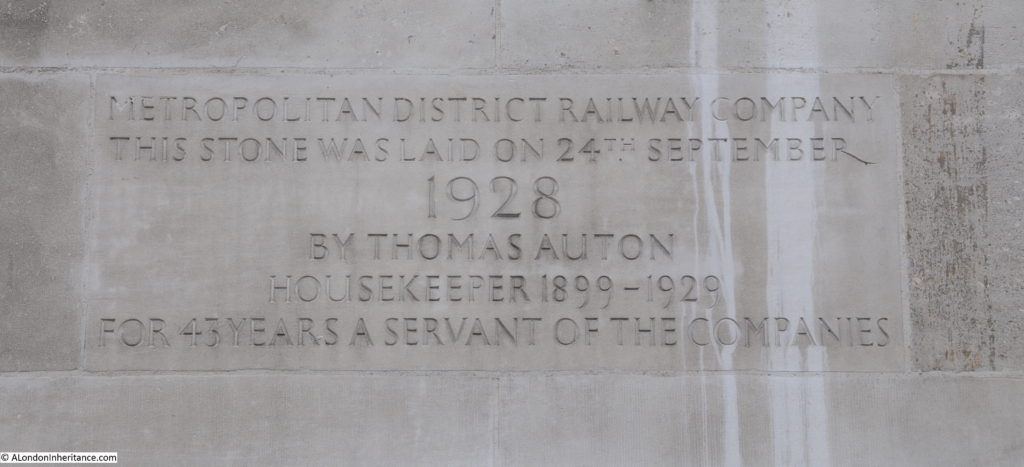

There are also a couple of unusual foundation stones, laid by a long standing employee:

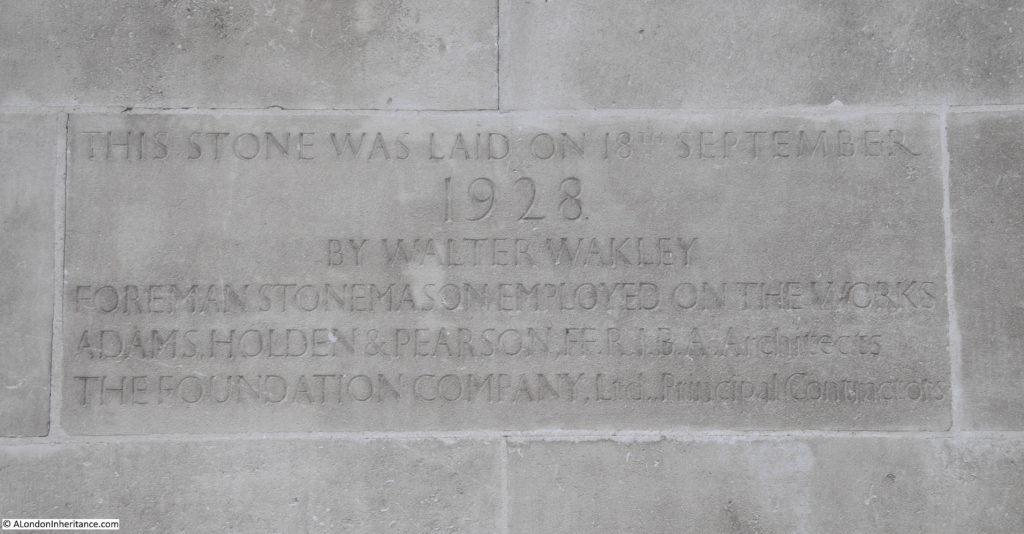

And by one of the foreman stonemasons employed on the construction of 55 Broadway:

On entering the ground floor reception of the building there is an original Train Interval indicator. The information on the central panel reads “The passing of a train at a given point on each Underground Railway causes a stroke to be marked on the dial of the clock. These strokes therefore indicate the number of trains run in each hour.”

There is a clock display for the District, Metropolitan, Central, Bakerloo, Piccadilly and Northern Lines.

The interior of 55 Broadway retains many of the original features. Wood frame doors with glass panels leading off each lift lobby to the office areas.

View from the lift lobby to the wood paneled Directors corridor:

The Directors corridor. The Underground Company, along with many other large companies of the time, was very hierarchical and the status of the employee was reflected in their surroundings. The high ceilings and expensive wood paneling of the Directors offices clearly show their status within the company.

The quality of the workmanship and the cost of the materials is still very apparent after almost 90 years. Note the original brass door handles and the very long door finger plates:

The largest office on the floor at the end of the corridor:

Original stairwell features:

Original lighting feature:

Looking from the stairs at the doors which lead into the lift lobby, again the original doors. This is the 6th floor as indicated by the number which was needed as each of the floors looks identical.

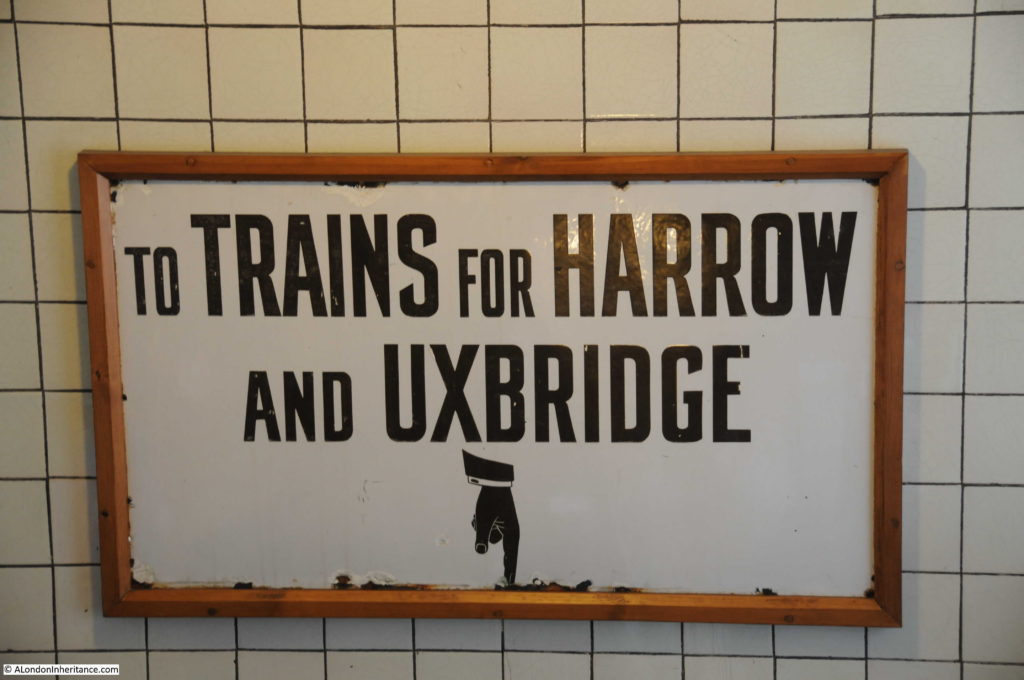

Signs from London Underground’s past have been added to the stairwell.

Even in the stairwell, the level of detail in the tiling indicates the amount of work and money that went into 55 Broadway:

There are two external levels at the top of the building. The first provides a good view of the tower:

And the clock:

But it is from the top of the tower that the best views of London can be found. Here looking towards Westminster with the Shard in the background, London Eye to the left and the towers of the Barbican on the left edge of the photo:

Around the edge there are panels providing information about the view and the key features to be seen:

The view at this level allows some of the external features to be seen slightly better than from the ground. Here is one of the original rainwater hoppers which displays the year 1929, but also includes the underground symbol with the large U and D letters that began and ended the uppercase UNDERGROUND with a smaller size of the font used for the letters between the U and D.

View towards the north-east. The BT Tower on the left across to the Barbican on the right. The green trees of St. James’s Park provide a contrast with the built city.

On the day of my visit, the weather was overcast with the threat of rain, so the views were rather hazy, but I always find it interesting to look across London from a high point.

The BT Tower with Euston Tower in the background:

The Ministry of Defence buildings in the foreground and the towers of the Barbican in the background:

A hazy St. Paul’s Cathedral. It is from these high points that the topography of an area becomes clear. 55 Broadway being close to Victoria and north of the river, you might expect to look along the north of the city to see St. Paul’s, however as can be seen the view is across the south bank of the river and the Royal Festival Hall:

The London Eye with the towers of the City in the background. The cranes immediately behind the London Eye are constructing the new towers that will soon surround the old Shell Centre tower.

As a slight diversion from 55 Broadway, the Shell Centre Tower has the most complex scaffolding I believe I have ever seen, stretching from ground to the top of the tower. I walked past the Shell building earlier this past week and took the photo below. No idea what construction work demands this level of scaffolding.

Yet more cranes, this time round the Battersea Power Station development:

Towers of existing apartments at Vauxhall:

The information panels around the top of 55 Broadway’s tower show how quickly the view can change. In this panel looking towards the south-west, a large office block is shown obscuring much of the view:

The office block is currently being demolished, revealing a view from the top of 55 Broadway which has not been visible for many years, although no doubt an equally high tower will soon be built.

55 Broadway is an extraordinary building and its design reflects the ambitions of the London Underground in the 1920s and how the Underground was seen as the modern way of travelling across the city.

Transport for London, the current descendant of the 1920s Underground Company are relocating to new headquarters in the Olympic Park, which is understandable given the limitations of a 1920s building for today’s ways of working requiring flexibility of space and a dependency on IT services across the building.

I understand that whilst Grade I listing protects much of the internal and external features and structure of the building, the future use of the building is still uncertain. I suspect, given what typically happens to redundant buildings in central London, the future of 55 Broadway will be either luxury apartments or as a hotel. A sterile and repetitive outcome which will be a waste of such a wonderful building.

The London Transport Museum’s Hidden London tours of 55 Broadway are currently sold out, however if more become available I really recommend taking a tour of this fascinating building.

Thanks. This was really interesting.

Excellent. Our group – London Historians – did two tours last year. Hoping to do another the next few months. Important to get in for a look-see before the developers get their grubby mitts on it.

I drive past this building often, and I found this very interesting. Next to 55 Broadway is a short road called St Ermin’s Hill. I have always wondered why it has this name, because it is perfectly flat, and not a hill at all. I know the underground station used to be open to the sky before 55 Broadway was built, so I wondered if the road used to go downhill to the station, but this does not seem likely.

I guess the office building being demolished is the old New Scotland Yard.

Pity, really.

Brilliant post again BTW.

“The largest office … at the end of the corridor” was occupied by Lord Ashfield as Chairman of London Transport and his successors until about 2006.

The British Transport Commission also had offices within 55 Broadway from its formation in 1948 for several years.

Thanks, always, for an interesting post! That historic building surely needs a good cleaning. I remember how black Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris was when I first saw it in 1957 (yes, I am THAT old)..and what a lovely difference after it had been cleaned.

And as for the views of the river..WHAT view? Hate it when that happens..

Hate it here in Phoenix, AZ when new buildings are built right out to the street and I can not longer see the mountains that I love so well. Sigh..

Thanks for this. I passed 55 Broadway every day on my way to school, and came to know the Epsteins in particular very well. It was good to have a chance to tour the inside of the building at last. Thank you!

It was my station for school too, but I don’t think I ever raised my eyes high enough to see the Gills, nor did I realise it was cruciform till I saw the shot from Britain from Above. I always loved the train interval indicators which were still high tech in the ’60s. What was the dome in the Britain from Above photo? Is it on the Home Office site or Wellington Barrcks?

Even more secrets in the red brick building over the road, for decades MI6’s never-to-be-admitted ‘Office’.

Colin

The dome in the aerial photo is part of the Wellington Barracks site, so was probably a roof over the horses’ indoor exercise yard.

The aerial photo was taken before the Home Office building was constructed. The building shown is Queen Anne’s Mansions, which at the time was the tallest residential block in London.

The dome in the aerial photo was part of Niagara Hall, which was originally built in the 1880s. In 1895 the building was converted into an ice rink but that lasted only until 1902. For much of its remaining life Niagara Hall was used as a garage. A letter published in The Times in early August 1939 said that the building “is about to be pulled down to make way for a block of flats”. I can’t find any information about when the building was actually demolished. Since the war started less than a month after the letter, perhaps it survived until after the war.