Walter Thornbury’s opening description of Ely Place in Old and New London is a perfect summary: “A little north of St. Andrew’s, Holborn, and running parallel to Hatton Garden, stand two rows of houses known as Ely Place. To the public it is one of those unsatisfactory streets which lead nowhere; to the inhabitants it is quiet and pleasant; to the student of Old London it is possessed of all the charms which can be given by five centuries of change and the long residence of the great and noble.”

From St. Andrew’s church, cross the approach to Holborn Viaduct, then across Charterhouse Street, we can see the entrance to Ely Place:

Thornbury’s description hints at the long and complex history of the street and surroundings, and the gatehouse at the entrance to Ely Place confirms that this is not a normal London street.

Much of the street remains lined with houses from the 1770s development of Ely Place, although many have been modified and restored, and there was considerable bomb damage to the area during the last war, however the view still demonstrates what a fine late 18th century London terrace would have looked like:

Along the western side of Ely Place is a curious indentation in the terrace, and here we can see the church of St. Etheldreda, with to the right Audrey House, which according to the Camden Council “Area Appraisal and Management Strategy” is 19th century. I assume late 19th century (Audrey was another version of the name of Etheldreda):

View looking south. The terrace house immediately to the left of the church has a strange ground floor, which I will discover soon:

As Thornbury hinted, Ely Place has a very long history.

In the 13th century, the land appears to have been in the possession of John de Kirkeby, Bishop of Ely, as on his death in 1290, he left the land and nine cottages to his successor Bishops of Ely.

It was normal in the medieval period for important figures in the church to maintain a residence in London. This was so they had somewhere to stay when visiting the city, where they could entertain, and to ensure that although they might be representing places far across the country, they could still have a presence close to the centre of royal and political power.

The Bishops of Ely originally had a house in the City of London, however there seems to have been a falling out with Hugh Bigod who was the Justiciary of England in the mid 13th century, and who tried to deny them access to their property in the Temple. It may have been this event which either gave John de Kirkeby the idea, or he was persuaded, to leave the land following his death to the Bishops.

The Bishops won a legal case to continue use of their City house, but following the bequest of such a large area of land, in the still semi-rural area to the west of the City, it must have seemed a good idea to build a new London home for the Bishops of Ely.

The Bishops than started the development of the land, into a property suitable for use as their London home. A chapel to St. Etheldreda was probably one of the first buildings on the site, along with the bishop’s house. William de Luda, the bishop that followed John de Kirkby purchased some additional land and houses and left these to the Bishops of Ely on his death.

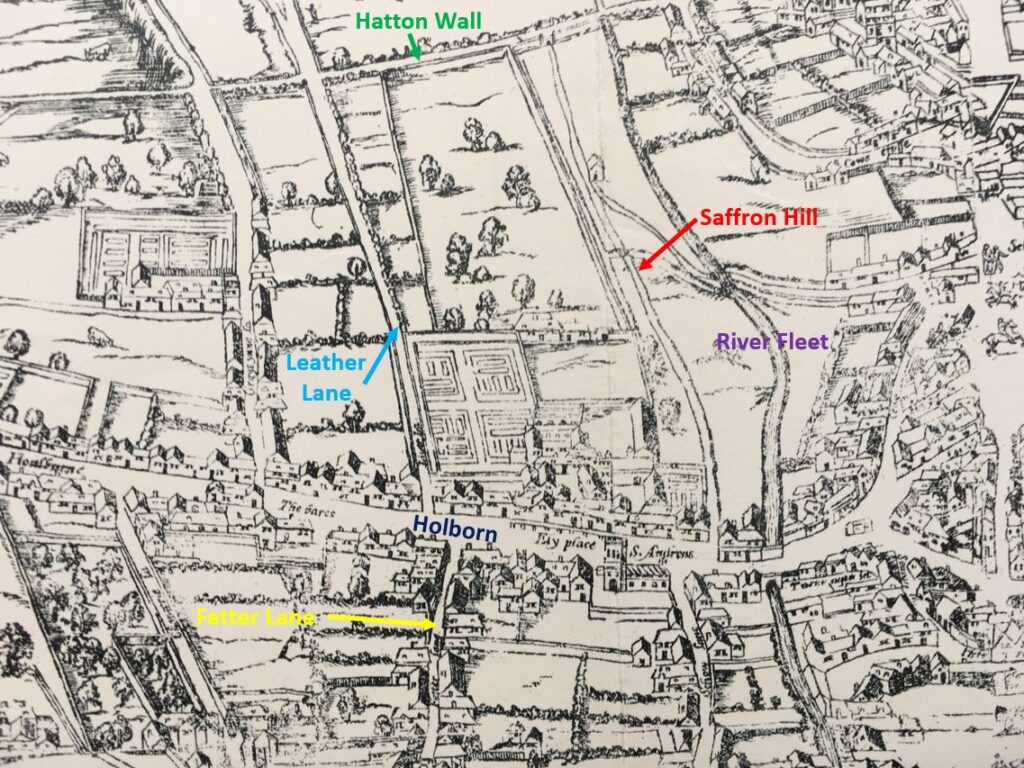

The house and grounds were continuously added to, and developed during the 14th century, and we can get an idea of the size of the place from the so called Agas map from around 1561:

I have marked the streets that formed the boundaries to the Bishop’s land, Holborn to the south (you can see the name Ely Place and St. Andrew’s church just to the right of where I have marked Holborn).

Saffron Hill is to the east, then just a lane winding along the top of the bank down to the River Fleet. Hatton Wall formed the boundary to the north and Leather Lane (identified using its earlier name of Lither Lane) to the west. To confirm locations, I have also marked Fetter Lane in yellow to the south of Holborn.

The house and chapel were in the southern part of the estate, with gardens and extensive grounds up to Hatton Wall.

The quality of the fruit from the gardens must have been well known as Shakespeare has Richard III saying to John Morton, the Bishop of Ely:

“When I was last in Holborn,

I saw good strawberries in your garden there

I do beseech you send for some of them.”

Ely House also appears in Richard II, where the dying John of Gaunt includes the following well known lines:

“This royal throne of kings, this scepter’d isle,

This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars,

This other Eden, demi-paradise,

This fortress built by Nature for herself,

Against infection and the hand of war,

This happy breed of men, this little world,

This precious stone set in the silver sea,”

John of Gaunt did stay in Ely House from 1381 until his death in 1399. His London residence at Savoy Palace had been destroyed during the Peasants Revolt. John of Gaunt was one of those that the leaders of the revolt demanded to be handed over for execution.

Other visitors to Ely House included Henry VII who attended a banquet in 1495 and Henry VIII with Catherine of Aragon, who both attended the final day of a five day “entertainment” in November 1531. A prodigious amount of food was recorded as being consumed during the five days.

The extract from the Agas map shown above dates from around 1561, and the grounds of Ely House would soon start to be developed.

Queen Elizabeth I required that the Bishop of Ely lease part of the grounds to her Chancellor, Sir Christopher Hatton in 1576.

Hatton started the developed of the land, which included construction of a new house for him in the gardens. The lease would stay in the Hatton family until 1772 when the last Lord Hatton died. It then reverted to the Crown.

In the years of Hatton ownership, Ely House had a varied history. During the Civil War the house was used as a prison for captured Royalists, as well as a hospital for injured soldiers. The Bishops of Ely returned in 1660 to part of the property, but by then much had been developed and was held by the Hatton family.

We can get an idea of the development of the area in the years before the death of the last Lord Hatton from the following extract from a map of St. Andrew’s parish, dated 1755:

We can see a considerably reduced Ely Garden just to the north of Holborn Hill, with Ely House marked, and the chapel just below the word House.

Hatton Street (now Hatton Garden) had been built, and housing and streets had been constructed up towards Hatton Wall at the north, to Leather Lane in the west and Saffron Hill to the east. The banks of the fleet had also been built on by 1755, and the words “The Town Ditch” rather than River Fleet give some idea of the state of the old river by the middle of the 18th century.

The Bishops of Ely finally left the property in 1772, when they were given Ely House in Dover Street. This probably worked well as the above map extract shows, the area was heavily developed, and the house and grounds were in a state of disrepair.

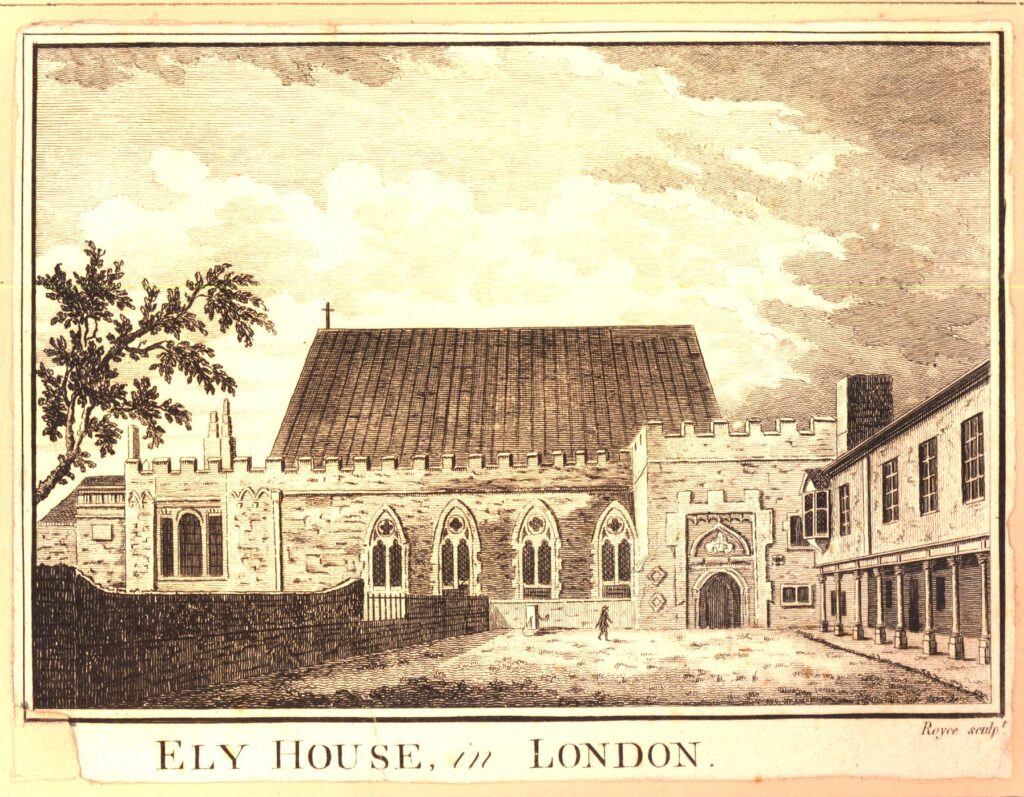

The following print issued in 1810, but probably drawn in the second half of the 1700s is recorded as showing Ely House in London (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

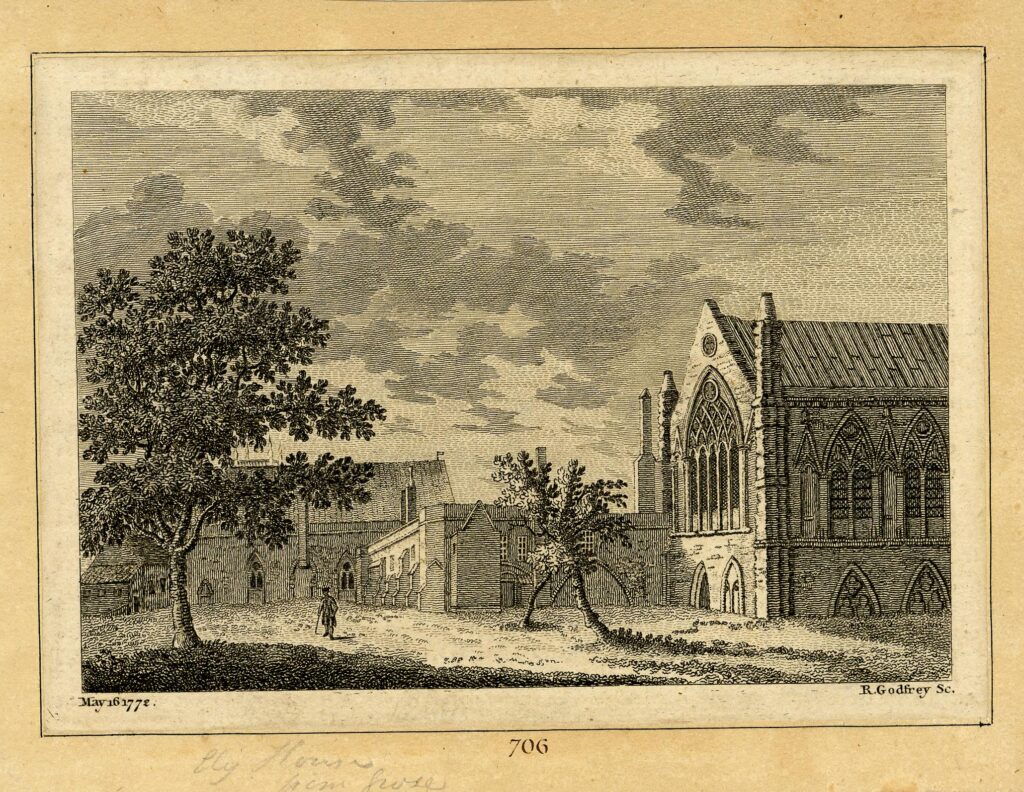

The view of the house in the above print does not look too much like the house shown in the parish map extract, however the following print dated 1772 from Grose’s Antiquities of England and Wales provides a better view as this shows the chapel on the right and house in the background, in the correct orientation as shown in the parish map (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

The parish map implies that there is an open space between the house and chapel, however in the above two prints, the two buildings appear to be connected.

The old chapel on the grounds of Ely House is the only structure remaining from the time when the Bishops of Ely owned the site. Today, recessed slightly from the street, the chapel is now the church of St. Etheldreda.

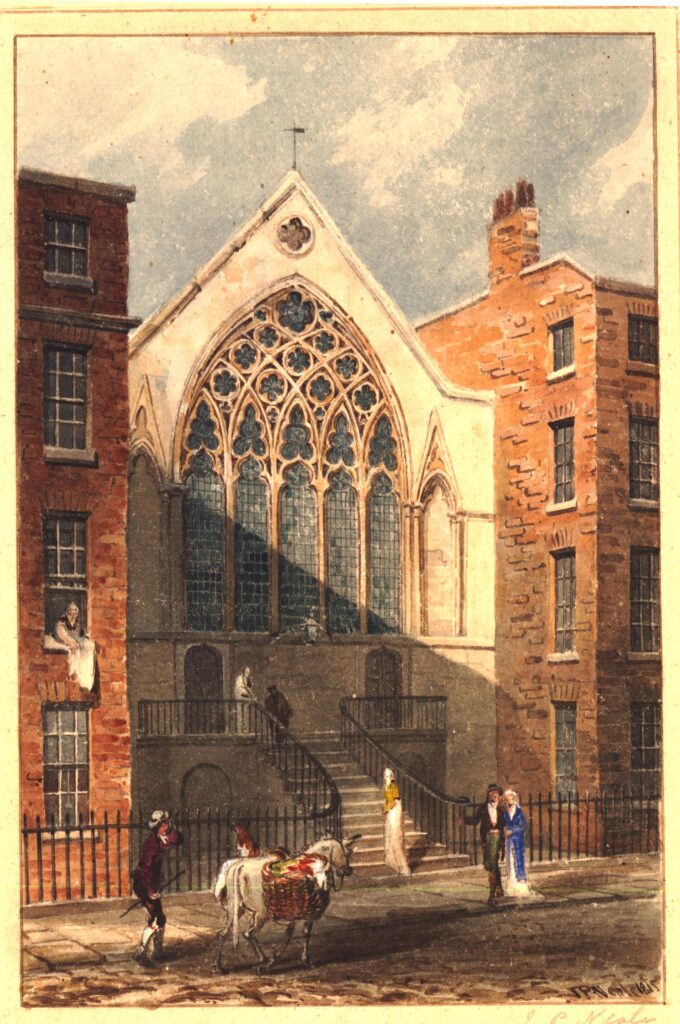

It is shown in this 1815 print, with the two late 18th century terraces on either side (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

The lower part of the church appears to have changed since the time of the above print. The original entrance looks to have been up some steps from the street and there seems to be two doors through into the church.

Today, if I have understood the layout of the church correctly, the altar would be behind these doors, so the church now has a different entrance, shown in the photo below:

Today, the entrance to St. Etheldreda is through a door into the ground floor of the terrace house on the left of the church. From here, the door leads through to a corridor that runs along part of the south wall of the church:

The church is dedicated to St. Etheldreda, and this dedication can be traced back to the Ely heritage of the church.

An 1825 newspaper description of Etheldreda provides some background:

“This day, October 19th, is the anniversary of St. Etheldreda; she was a Princess of distinguished piety, and daughter of Aunas, King of the East Angles, and Heriswitha, his Queen, and was born in the year 630, at Ixning, a small village in Suffolk; at an early age she made a vow of perpetual chastity, which is recorded she never broke, though she was twice married, first to Thombert, an English Lord, and afterwards to Egfrith, king of Northumberland, in 671. Having lived twelve years with this King, she retired from the world, and devoted herself to God and religious contemplation, erecting an Abbey at Ely, of which she became superior, and where she spent the remainder of her days.”

There appears to have been a bit more to her “retiring from the world”. She had married Egfrith when he was aged 15, but by age 27 he wanted a more normal marital relationship. Egfrith tried to bribe Etheldreda, but she was standing firm and left him, becoming a nun at Coldingham, before going on to found an abbey at Ely.

Ely Cathedral was dedicated to Saints Peter, Etheldreda and Mary in 1109, and the Bishops of Ely carried the dedication to Etheldreda to their chapel in London.

Along the corridor is the entrance to the crypt:

But before looking at the crypt, there is an interesting feature just to the right of the door:

There was an article in a 1926 edition of the Illustrated London News, which discussed the Roman City. The article states that “Equally curious is the fact that digging has revealed only the slightest signs of Christian worship in Roman London, although it is known that there was a Christian community in Londinium, and that it was ruled by a Bishop as early as the third century. The chief ‘clue’ is at St. Etheldreda’s Church, Ely Place. It is a curiously archaic bowl shaped font of limestone of similar form to the two which are preserved at Brecon Cathedral. it was found buried in the undercroft.

Of the St. Etheldreda’s font, Sir Gilbert Scott said ‘You may call the bowl British or Roman, for it is older than the Saxon period’; and some support to this statement is provided by the fact that Roman bricks have been found on the site.”

A quick Google for the Brecon fonts shows these to be Norman, not early Christian, and the main font in the church does look like the Brecon font, so I have no idea whether this feature on the wall is the one referred to in the article, whether the article is right, and whether St. Etheldreda had, or has an early Christian font.

A walk down into the crypt reveals a dimly lit space, presumably with seating laid out for a function such as a marriage:

Niches in the walls with religious symbolism:

The crypt is very different to how it was many years ago. In May 1880, members of the St. Paul’s Ecclesiological Society visited St. Etheldreda’s and their description of the church includes some history on the crypt:

“The members of the St. Paul’s Ecclesiological Society held their second afternoon gathering for the present summer on Saturday, and inspected the chapel of St. Etheldreda, in Ely-place, Holborn. At the construction of the chapel, which was formerly the private chapel of the Palace of the Bishops of Ely, was fully explained by Mr. John Young (the architect under whom the fabric has recently been renovated throughout), who discoursed on its early history and on the salient points of its chief architectural features, its loft oak roof, its magnificent eastern and western windows, full of geometrical tracery, its lofty side lights, its ancient sculptures, and lastly its undercroft or crypt, which till very lately was filled up with earth and barrels of ale and porter from Messrs. Reid’s brewery close by.

Removing the earth from the crypt, it may be remembered, there were discovered the skeletons of several persons who had been killed 200 years ago by the fall of a chapel in Blackfriars, and were here interred.

The ‘conservative’ restoration of the fabric – in the general plan of the late Sir George Gilbert Scott, had been frequently consulted – was much admired by the ecclesiologists.”

The fall of a chapel in Blackfriars occurred on the afternoon of Sunday 26th of October 1623, when around 300 people had assembled to hear a Catholic sermon by the Jesuit preacher, Robert Drury, at the French ambassador’s residence.

As it was a Catholic sermon, the congregation of people was considered illegal.

The roof of the hall in which the sermon was underway collapsed and around 100 people were killed. Rather than any sympathy, anti-Catholic feeling at the time unleashed a religious riot at the site of the tragedy.

I understand that the skeletons of those who died at Blackfriars, and were buried and subsequently discovered in St. Etheldreda’s were reburied, and still rest in the church.

View from the rear of the crypt:

One of the niches that line the crypt walls:

The church above is a lovely space. I do not know if this is the normal form of lighting, but it added to the impression of the age and history of the church. Very different to the typical brightly lit London church:

St Etheldreda was caught up in the religious changes brought about by Henry VIII and the dissolution of the monasteries.

The mass which had been celebrated by the Bishops of Ely in the Church of St Etheldreda since it was first built in the 13th century, was abolished, and the Book of Common Prayer became the standard for religious services.

Apart from a short period of five years when the Catholic Queen Mary was on the throne, the Catholic service was banned, and anyone participating in, or preaching a Catholic service would be treated as a criminal, with a death sentence often the result.

A special allowance was made in 1620 when the Spanish Ambassador, the Count of Gondomar, moved into Ely Place. Due to his position as Ambassador, and the custom that the ambassadors residence and grounds are considered part of the country they represent, which in the case of Spain was a Catholic country, Catholic services were allowed to be held in St. Etheldreda’s.

When Gondomar was recalled to Spain, his replacement was not allowed to take up residence at Ely Place, and permission for Catholic services was removed.

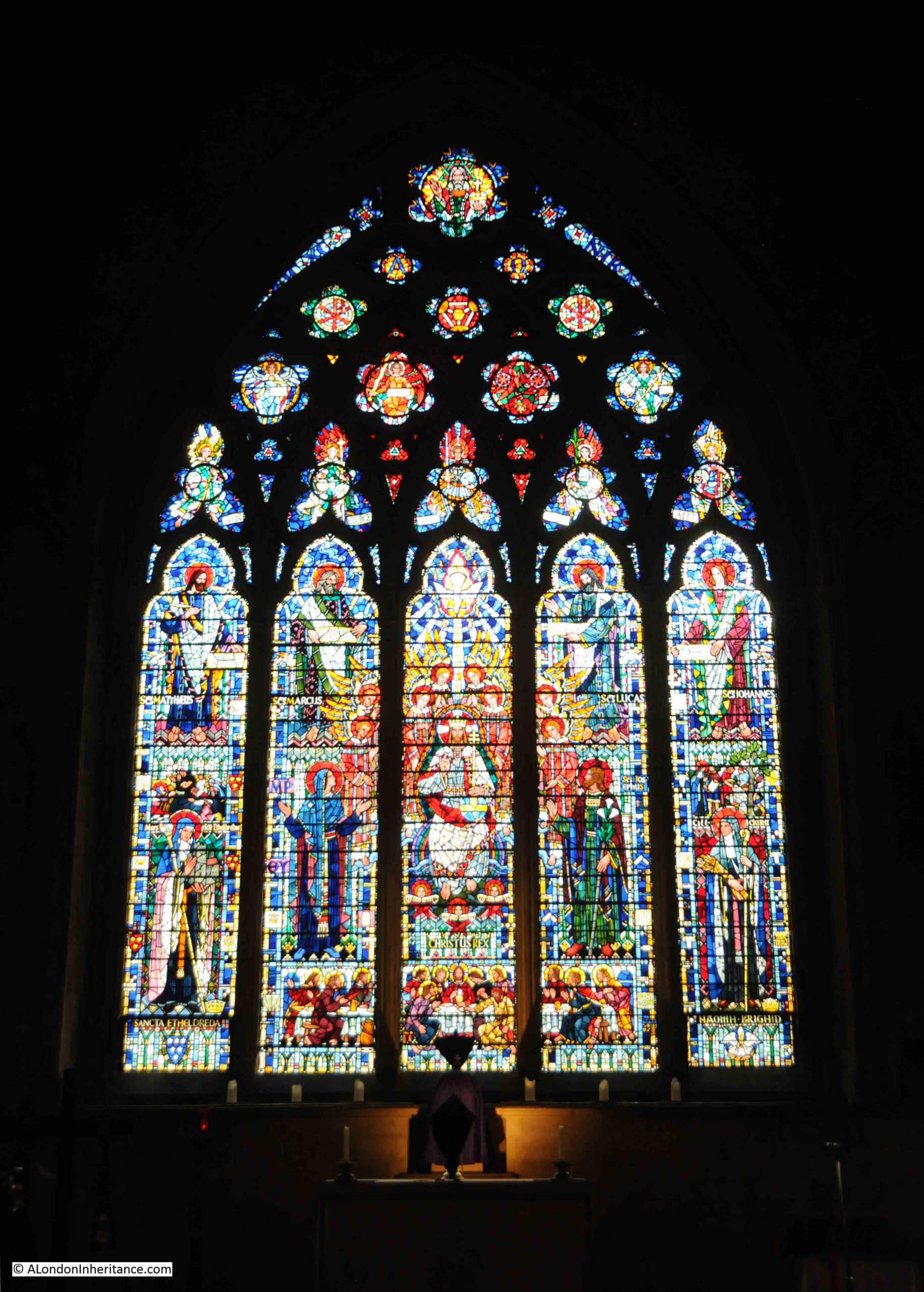

Detail of the stained glass above the altar:

The church was included in the use of Ely house and grounds as a hospital and prison during the Civil War.

Anti-Catholic feeling can be seen in the treatment of the uncle of Sit Christopher Wren. Matthew Wren was Bishop of Ely and tried to restore the grounds of Ely Place from the Hatton family, however he was reported for his “Popish ways” and imprisoned in the Tower of London. When he was finally released, the land which he had tried to restore had been built over and was very much as shown in the earlier parish map extract.

The change to the way that the State viewed the Catholic faith started in 1829 when the Catholic Emancipation Act was passed. This Act allowed Catholics to have their own churches, and for the Catholic mass.

In 1843, St. Etheldreda’s church opened as a Welsh language church, however the church reverted to the Catholic faith in 1873 when the church was purchased by the Rosminians – a Catholic congregation also called the Institute of Charity.

The church has featured in commemorations of Catholics who had been executed in earlier centuries. In 1912, it was reported that “Several hundreds of ‘the faithful’ marched in procession on Sunday afternoon from Newgate to Tyburn, along the route followed by the Catholic martyrs in a less tolerant age. The pilgrimage is the third of its kind, having been inaugurated three years ago.

Following the Crucifix, which was held aloft by Father Fletcher, came 150 men who marched in front of 190 women, most of whom recited prayers along the route.

The first stop was at the church of St. Etheldreda, the ancient church of the Bishops of Ely at Holborn. Thence the procession, the numbers of which increased with every mile covered, visited in turn the Catholic Church in Kingsway and St. Peter’s, Soho, and finished up at the Convent, near Tyburn.”

A sign today outside the church states that it was returned to the Old Faith in 1874 and that it continues in the care of the Rosiminian Fathers.

View towards the rear of the church:

Side windows of stained glass:

St. Etheldreda’s was badly bombed during the last war. There was significant damage to the roof and all the original stained glass was lost. When one bomb fell, there were people sheltering in the crypt, luckily there were no casualties.

The church was restored over the following years, and officially reopened on the 2nd of July, 1952 as commemorated by a plaque embedded in the wall under the Royal coat of arms:

Walking back outside, and along the corridor there must have once been a café on the other side of this door, with an old Luncheon Vouchers sticker on the door:

Back in Ely Place, and it is officially a dead end, although there is a doorway through to Bleeding Heart Yard, which the general walker is encouraged not to use:

There is some rather wonderful tiling on the blank arches at the end of the street which presumably also records the date when this wall was built:

On the western side of Ely Place is an entrance to Ely Court:

Along the alley is the pub Ye Old Mitre:

The Mitre (a bishops hat) is believed to have been founded in 1546 for the servants at the Bishop of Ely’s house, although the present buildings are later. The Grade II listing of the building states that it is “Circa 1773 with early C20 internal remodelling and late C20 extension at rear”, and that “near entrance glazed in to reveal trunk of what is believed to be a cherry tree, marking the boundary of the properties held by the Bishop of Ely and Sir Christopher Hatton”. There are also stories that Sir Christopher Hatton and Queen Elizabeth I danced around the tree, however I always find such stories somewhat doubtful.

The Mitre seen from further along the alley shows the late 18th century origins in the architectural style of the building:

On the front of the building is a mitre, and I have read some sources that state that this is from the original Ely House, however I can find no early source for this, and it is not stated in the Historic England listing details so I am dubious that it is from the original house:

Again, only a very brief description of a place with so much history, and a church that tells much about the state and country’s attitudes to the Catholic faith over the last five hundred years.

Ely Place was once a part of the church of Ely in London. Many of the rights associated with such a status have been removed over the last couple of hundred years, however it is still a very distinctive place, and the street and St. Etheldreda are well worth a visit.

Fascinating so much history in one place a really good read.

Thank you for this very informative tour. It’s great to see how the site developed over the centuries, with the visual support of the maps. Thank you for your research.

Could you expand on this rather cryptic statement?

‘Back in Ely Place, and it is officially a dead end, although there is a doorway through to Bleeding Heart Yard, which the general walker is encouraged not to use’

The gate does give access to Bleeding Heart Yard but it’s generally locked presumably because they want to encourage people to use it as a cut through. I have walked through ti a couple of times over the years but it’s usually locked.

The gate does give access to Bleeding Heart Yard but it’s generally locked presumably because they don’t want to encourage people to use it as a cut through. I have walked through it a couple of times over the years but it’s usually locked.

A wonderful post – once again, the depth and quality of your research astounds me. Thank you.

Thank you for a very interesting post about London History.

Thank you for a very interesting post about Ely place and London History

I was hoping for a commentary on the quality of The Mitre…. but then I was only looking to have my prejudices confirmed. I take the waters there as often as I am able.

Excellent article, The Mitre is a smashing wee pub spent many a happy hour there over the years

Thank you this post! I worked just down the road for many years before retiring and used to spend lunch breaks enjoying the quiet space of St Etheldreda’s, I recall the building next door is still a working nunnery, and usually had a queue outside waiting for food. For some years, the nuns operated a lunch cafe offering reasonably priced hot meals just opposite the crypt. There are some gory tales about bleeding heart yard, as well as the Scots Whisky Society! Thanks again!

Another fascinating article, thank you.

I visited the Ely Place chapel several years ago now and knew something of its history, but I’ve learned a lot from reading this. Somehow, I missed the crypt (perhaps it was closed at the time of my visit).

Yes, you can be sure the altar is and always was at the Ely Place end of the chapel behind / between the two doors shown. It’s very much the norm for the altar in an old Church of England / Roman Catholic church to be at the east end. I remember thinking that the layout seemed odd when I visited – enter at one end, follow a corridor, then turn to enter the chapel from “the back”. (For those who don’t know: the C of E was part of the RC church until the reformation. Henry VIII did not “found the Church of England” as is so often stated: he made himself the head of the existing Church of England, in place of the pope. The C of E was formed in the 7th century.)

There is an irony in the presence of the Royal Arms to mark to mark the reopening of a Roman Catholic chapel in 1952. All C of E churches should show the Royal Arms in a prominent position, to remind the congregation that the monarch (not the pope) is the earthly head of the church.

I don’t quite see the link between John of Gaunt’s words you’ve quoted from Shakespeare’s Richard II and Ely House.