I have a real addiction to maps, almost any type of map. Folding maps, maps in books, street maps, transport maps – they all fascinate me. Whenever we go anywhere new, other people will be using their phone to guide them, I will have brought a paper map.

I probably have far too many maps of London, hidden away in shoe boxes in a cupboard. I feature John Rocque’s map and the 1940 copy of Bartholomew’s Reference Atlas of Greater London frequently in my posts, however I use many other maps to learn about how an area has evolved.

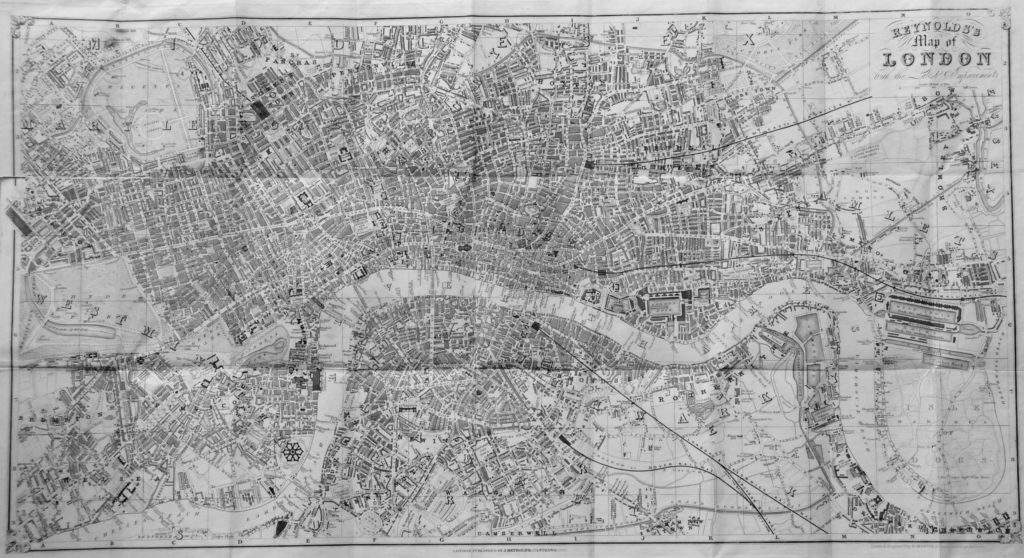

For a change, for today’s post, I thought I would feature one of these maps. This is “Reynolds’s Splendid New Map of London; Showing The Grand Improvements for 1847”.

James Reynolds was a London mapmaker with a shop at 174 Strand. The 1847 map was one of his first publications, and he would go on to produce regular updates to his London maps throughout the 19th century, also gradually incorporating colour into the maps. It is fascinating watch how London evolves with each new issue of Reynolds’s London map.

Many of his maps are online, however there is nothing better than the feel of an original paper map and to imagine the people who have used these maps to navigate the city – I did admit to having this strange addiction.

The map show features that have long disappeared and areas where key features have yet to be built.

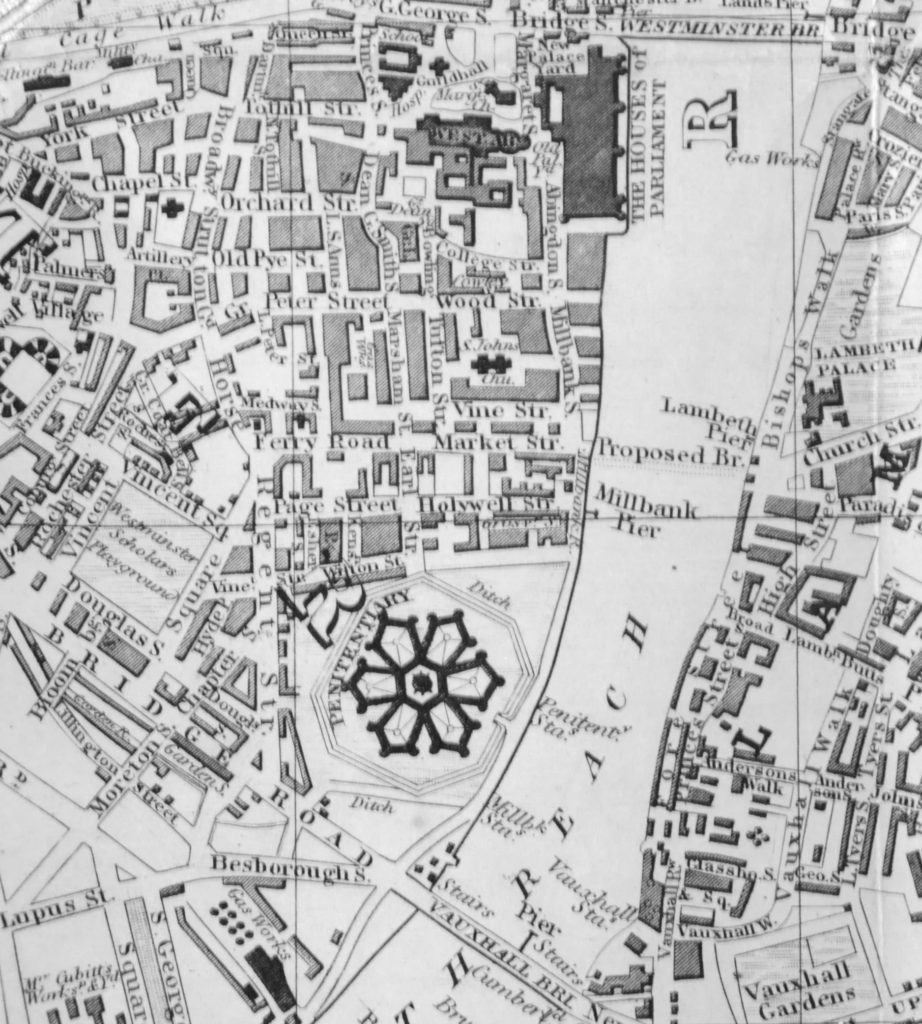

Take the following extract showing Westminster and Millbank.

The most distinctive feature is the hexagonal shape in the lower centre of the map. This was the Millbank Penitentiary or prison which occupied the site adjacent to the approach road to Vauxhall Bridge for much of the 19th century.

Although Vauxhall Bridge crosses the river, the rest of the river looks rather empty until Westminster Bridge, however look midway between the two bridges and there is the location of a “Proposed Bridge”. This was the site of the future Lambeth Bridge which would open in 1862.

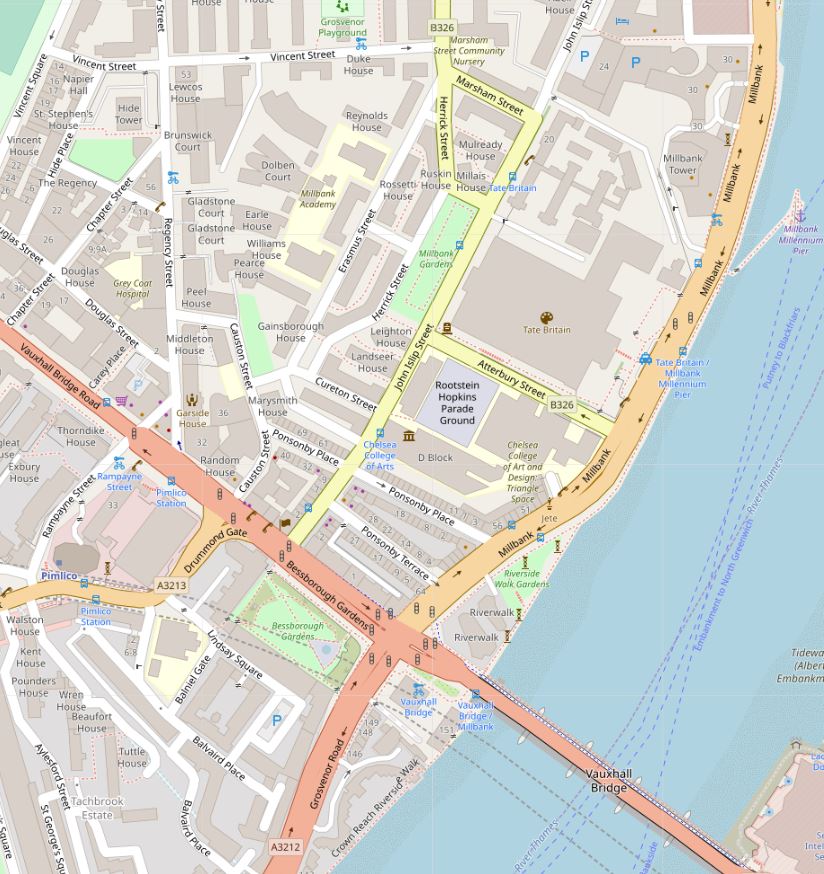

The area occupied by the prison can be easily located today, by referencing Vauxhall Bridge and Vauxhall Bridge Road, although the rest of the area has changed considerably. The following map extract shows the area today with the location of the prison now occupied by the housing to the north of Bessborough Gardens and up to Tate Britain. Map (© OpenStreetMap contributors)

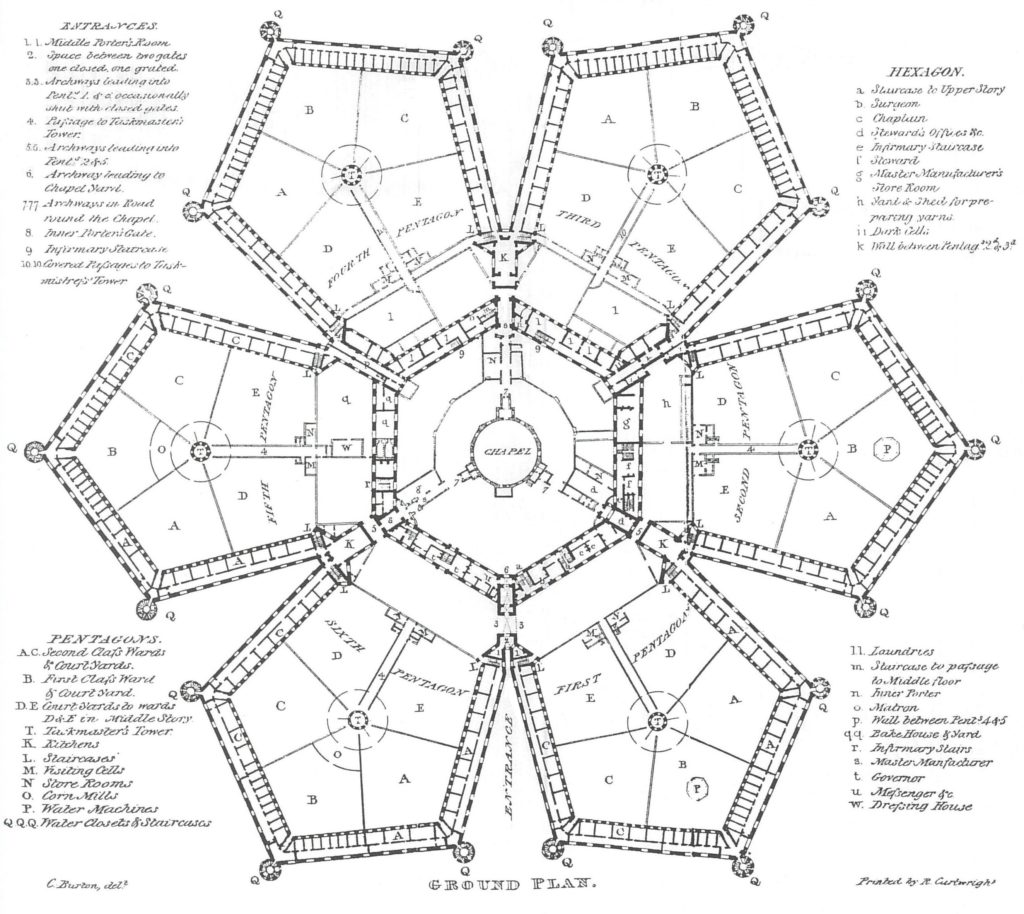

The geometrical shape of the Millbank Prison is shown in the following drawing from An Account of Millbank Penitentiary by G.P. Holford, dated 1828 and shows how the prison was divided into six pentagons arranged around a central chapel.

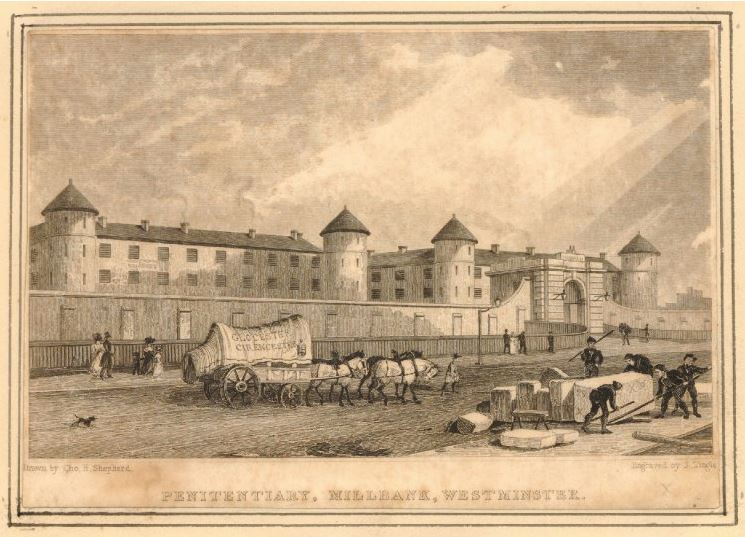

The following print from 1829 shows the prison – it must have been a forbidding place to be sent to – often before transportation to Australia (©Trustees of the British Museum).

The prison has a considerable history and a couple of traces of the prison can still be found today – a subject for a future post.

Let’s now head to the east of the map and visit the Isle of Dogs in 1847:

Nearly all of the Isle of Dogs is still marked a being “Marshes”. There is some building along the western edge and a couple of roads leading to the southern tip where the ferry provides a crossing of the river over to Greenwich.

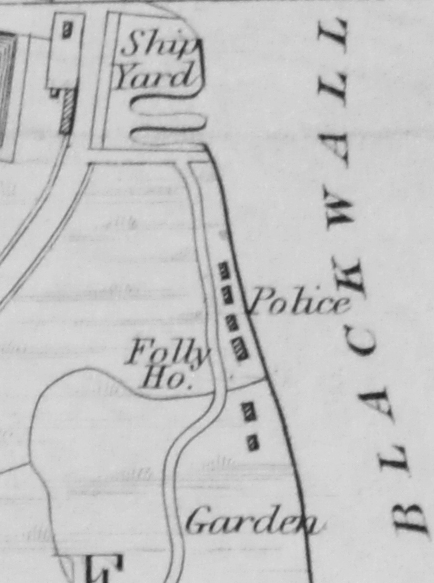

There are a number of interesting features on the map. The limit of building on the eastern edge was this little row of buildings, with the label “Police”. This was the location that the recently established Police force operated from before moving a short distance north to Coldharbour. Their primary aim was preventing theft from the shipping moored in the River Thames, the Docks and Warehouses.

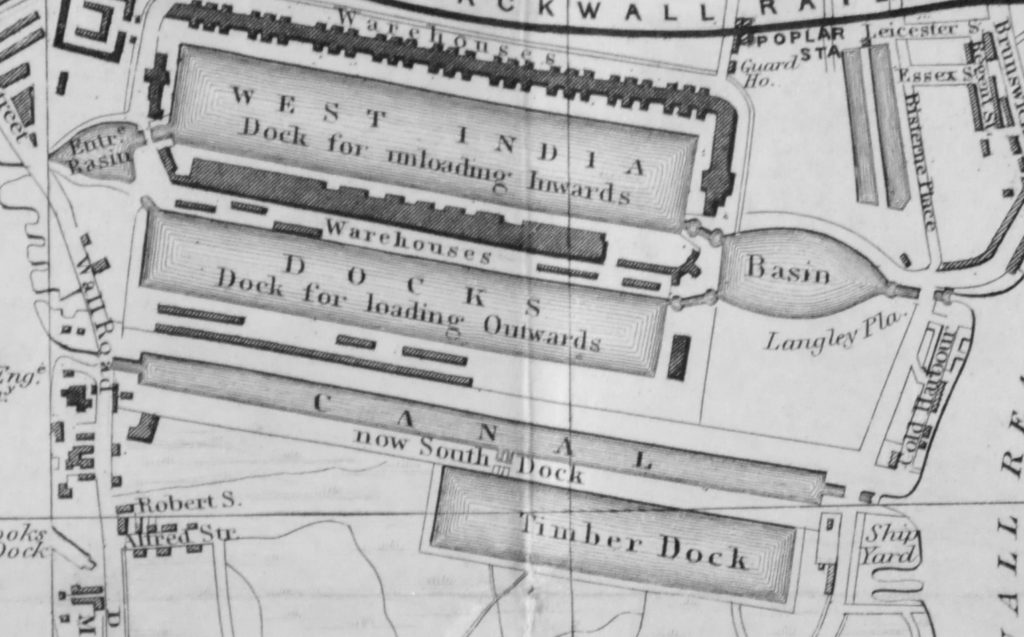

The first docks had opened at the start of the 19th century and would continue growing across the Isle of Dogs for the rest of the century. The following detail shows the West India Import and Export Docks. The full South Dock had not yet been built, the space being occupied by the Canal (which also served as a dock) that led between the east and west sides of the Isle of Dogs and the Timber Dock. Poplar Dock had yet to be built just to the north of the Basin on the right.

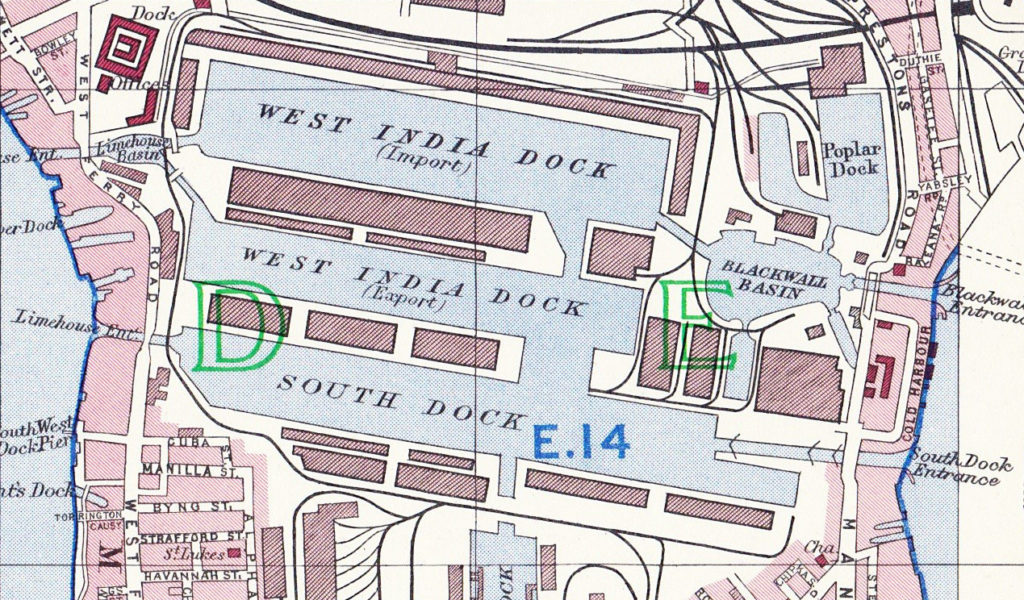

How the area looked when dock building had completed and be seen in the following map from the 1940 Bartholomew’s Atlas, showing the same area as the above 1847 map.

In the 1847 map extract, on the eastern edge of the Isle of Dogs between the Basin entrance and the Ship Yard is a street labelled Cold Harbour, with some building along the street. This is one of the earliest built streets on this stretch of the river.

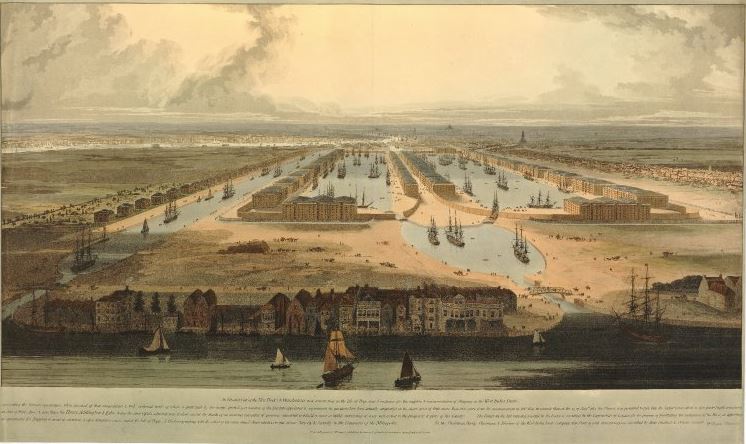

The artist William Daniell produced a series of prints of the new docks in 1802 and the following print shows Coldharbour as a line of buildings along the river front, between the entrance to the Blackwall Basin on the right and the South Dock to the left. (see my post where I explored the area which can be found here).

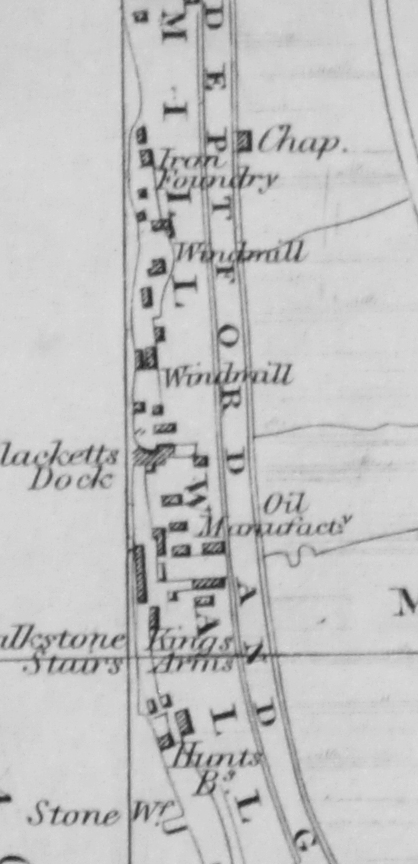

Industry has started spreading along the western edge of the Isle of Dogs. The following extract shows an iron Foundry and Oil Manufacturers, along with a couple of the windmills that once lined this edge of the river.

At the southern tip of the Isle of Dogs was a ferry across to Greenwich. The following extract shows the location of the ferry. The map also highlights the reason why much of the Isle of Dogs was labelled as Marsh as the land was below the high water mark – 7 foot at the southern tip.

Billingsgate in the City was not the only place in London where the name could be found – look across the river from the Ferry in the above map and there is a Billingsgate on the river bank at Greenwich.

Maps also show where the boundaries of the city’s growth were, and looking at maps over the years shows how the city gradually expands. In the following extract we can see that much of the land north of Limehouse and Poplar and east of Stepney was still open land in 1847. Bromley New Town has a few buildings, and to the north there is limited construction following the route of Bow Road.

The detail below from the above map shows the late 18th century Limehouse Cut running between the river at lower left and the Lee Navigation / Bow Creek at top right. The Limehouse Cut was built to provide a route to the River Thames whilst avoiding having to travel around the Isle of Dogs, and also avoiding the multiple bends in the lower section of the Bow Creek.

Industry alongside the Limehouse Cut includes a Rope Walk, Pearl Ash manufacturers, and a Patent Cable Manufacturer. Also, to top right, Bromley Hall is labelled. I found this building a couple of months ago when I walked from Bromley-by-Bow to the southern tip of the Isle of Dogs. The hall has survived to this day:

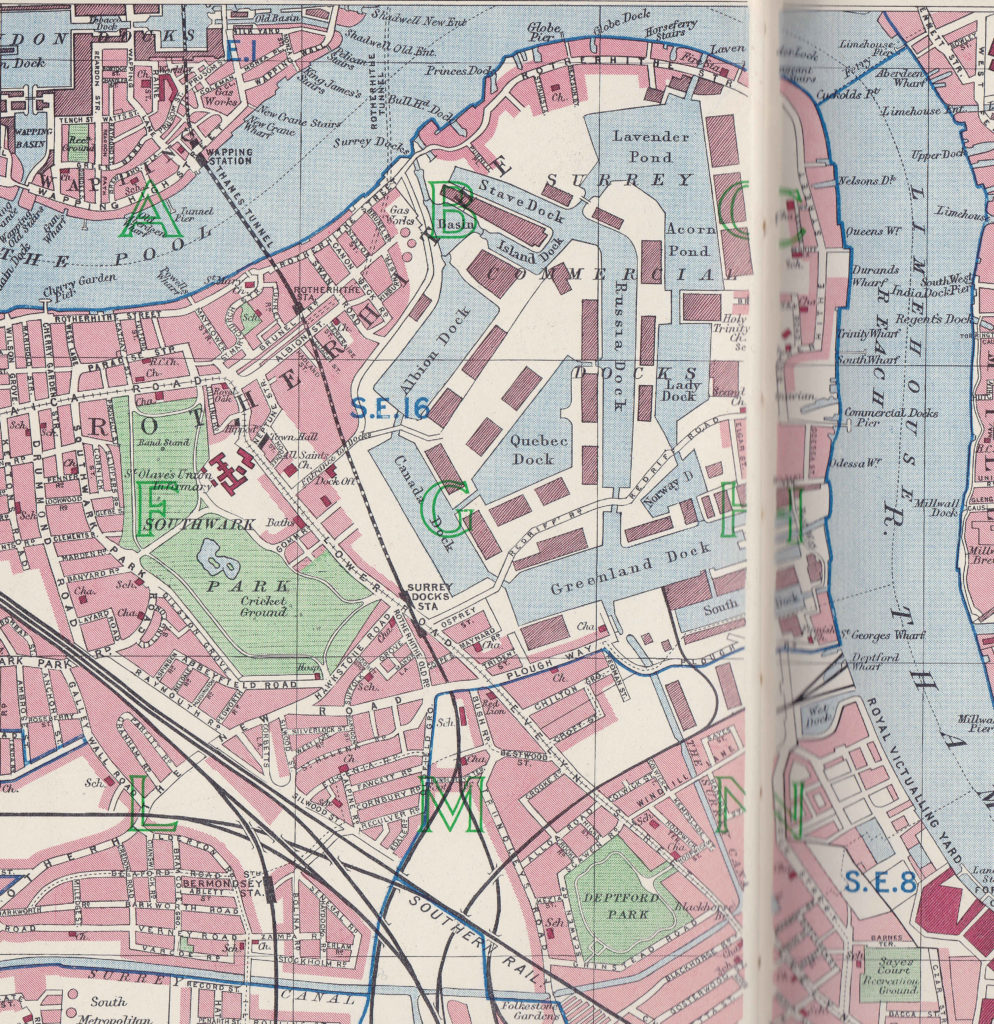

Crossing the river we can look at how far the Surrey Docks had developed by 1847.

The first docks were in place, and the Grand Surrey Canal provided a transport route from the docks to industries inland, reaching up to Peckham.

The map below from the 1940 Atlas shows the same area as the above map. The docks were at their peak and the rest of the land had been built up between 1847 and 1940.

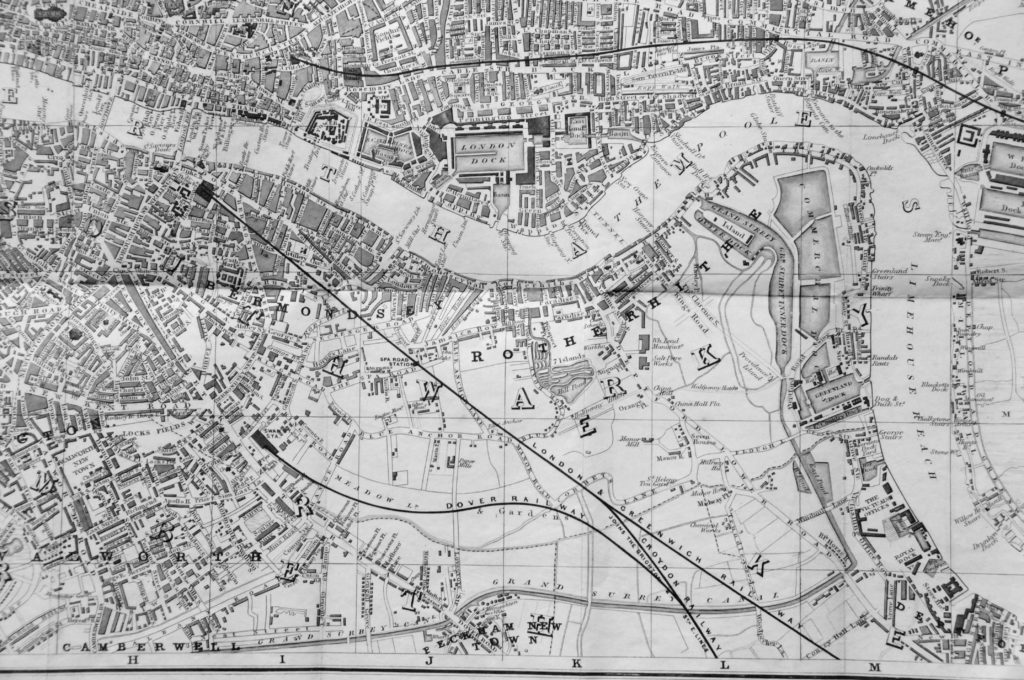

Zooming out there is another interesting feature. In the map below a long black lines stretches from upper left to lower right. This is the brick viaduct carrying the London & Greenwich Railway from the location of London Bridge Station out to Deptford and Greenwich. Much of the route is still through open land – this would soon be developed.

Heading back north again, and we can see one of the many developments across London where a name was given to a specific area. Many of these names can still be found in use today. In this example, we can see Globe Town.

The railways had not yet made their mark along what would become Euston Road. In the following map, the station that would become Euston Station is the black rectangle on the far left of the map.

St. Pancras and King’s Cross Stations have yet to be built. The reason that stations were built along Euston Road was a recommendation from an 1846 Royal Commission into the various railway schemes proposing stations in central London.

The Commission recommended that on the north of the river, railways should not be built through a central area of London bounded by the streets that would later become Euston Road, Marylebone Road, City Road, Bishopsgate which is why the stations serving central London form a ring around the outskirts of what was the centre of London in the 1840s.

If you look to the left of Euston Station, you will see St. James Chapel. The top right corner of the graveyard has already been lost to the first incarnation of the station, and the graveyard is currently being excavated today ready of the HS2 extension of Euston Station.

As well as stations not yet built, the 1847 map shows stations that have since disappeared.

The following map is an extract of one of the maps above and shows the London & Greenwich Railway as the straight line running from Deptford off to the right and London Bridge off to the left. Below this straight railway is the curved route of the Dover Railway, which ends at Swan Street Station, alongside what is now the Old Kent Road.

I have only seen the station called Swan Street Station a couple of times, it is better known as the Bricklayers Arms Station after a nearby pub.

The station was built by the Croydon and South Eastern Railway Companies, opening in 1844. The station was their alternative to the London & Greenwich Railway’s terminus at what is now London Bridge.

The station was advertised as a terminus for the West End and omnibuses were arranged to meet trains arriving at the station and take passengers onward to the City and West End. It was not a success and the passenger services ended in 1852 (apart from a brief resumption between 1932 and 1939). The station continued in use as a goods depot.

The Bricklayers Arms continued in a variety of railway related services until closure in the late 1970s and the sale of the land to developers in the early 1980s. The station and spur of the Dover Railway to the station has been demolished and replaced by commercial premises and housing.

If you look at the straight railway line above and to the right of Swan Street Station is another lost station – Spa Road Station which I wrote about here.

Spa Road Station as it appeared in 1836, eleven years before Reynolds’s map:

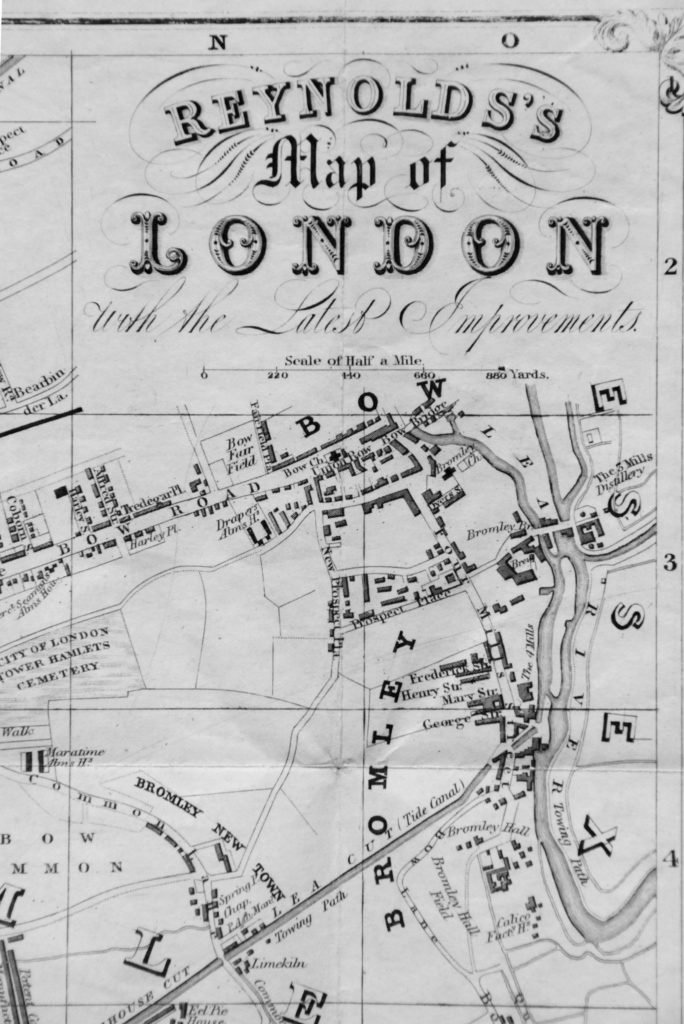

I have not really concentrated on the central city, rather focusing on the edges of the map as these were the area that were starting on their development from open land to the built-up city we walk around today. Another example can be found at the top right corner of the map where the original buildings of Bromley and Bow can be found.

Note that at the time, the River Lea formed the boundary with Essex. Greater London has since pushed many miles to the east.

One final look at something yet to be built in the following map extract with the Tower of London in the centre right of the map.

The landmark that is missing is Tower Bridge. In 1847 when the Reynolds’s map was printed, London Bridge was still the most easterly bridge over the River Thames.

The 1847 Reynolds’s Splendid New Map of London; Showing The Grand Improvements in its full glory:

As with photography, mapping today is mainly digital, and rather than exploring London with a paper map, today, visitors to London, or anyone else looking for a new location will almost certainly be looking at their phone.

I wonder how in 172 years we will be able to look back at maps of how London appeared in 2019? I will though continue my addiction and carry on buying paper maps.

Thanks for your amazing work on the development of London. We lived in London for 25 yrs before returning to Glasgow – great experiences and I enjoy being reminded of, or discovering, amazing places. I love yr dedication to te subject. Thanks!

Thanks. For those of us fascinated with local/London history maps are a never-ending source of information and pleasure. And pre-photography they provide us with “pictures”.

Thank you so much. Your enthusiasm is inspiring and so informative.

Very many thanks – your maps made my day!

I too prefer paper maps wherever I go. Ordnance Survey, tor the equivalent in another country. In London the A to Z for getting about. And historic maps for places I know well. But I must confess to a fascination with Google Maps satellite view when planing a trip to some where new.

I’m new to your site . What a find . Thank you for so much information and research .

I was born in East Ham – not on these maps but my grandparents were from Jubilee Street in Stepney and moved to East Ham after the First World War. Grandfather was a docker in the Millwall Dock, working there until his seventies. Grandmother was a tailor and both are long gone. I now live in Rotherhithe on what on the map is Island Dock, and a few yards from Surrey Basin, now with the more gentrified name Surrey Water.

Many thanks to the researcher who’s published this invaluable collection of fascinating information about London’s origin and development.

Love maps. It’s a special treat to find one in a book. Old paperbacks of mysteries often have a layout of the Manor or the village. Then there’s Erskine Childers Riddle of the Sands. Like the gentleman above I use Google and print out paper maps–because I am very directionally challenged

Well done sir another very informative read

I’ve been writing up the life of my great-uncle between 1896 when he arrived in London and 1920 when he left. Following his various addresses on historic maps proved an excellent way to chart his financial circumstances.

Looking at the maps of the Surrey Commercial Docks, it is interesting that there is only one solitary line connecting them to the main line network, and no evidence of the maze of sidings that clustered along the wharves of the East and West India and the later Royal Docks. Most of the products handled by the Surrey docks were lengths of timber handed by specialist stevedores called “Deal Porters” and my guess is that most went to the London furnishing and house building trades, and were therefore horse and carted I guess direct to the end user