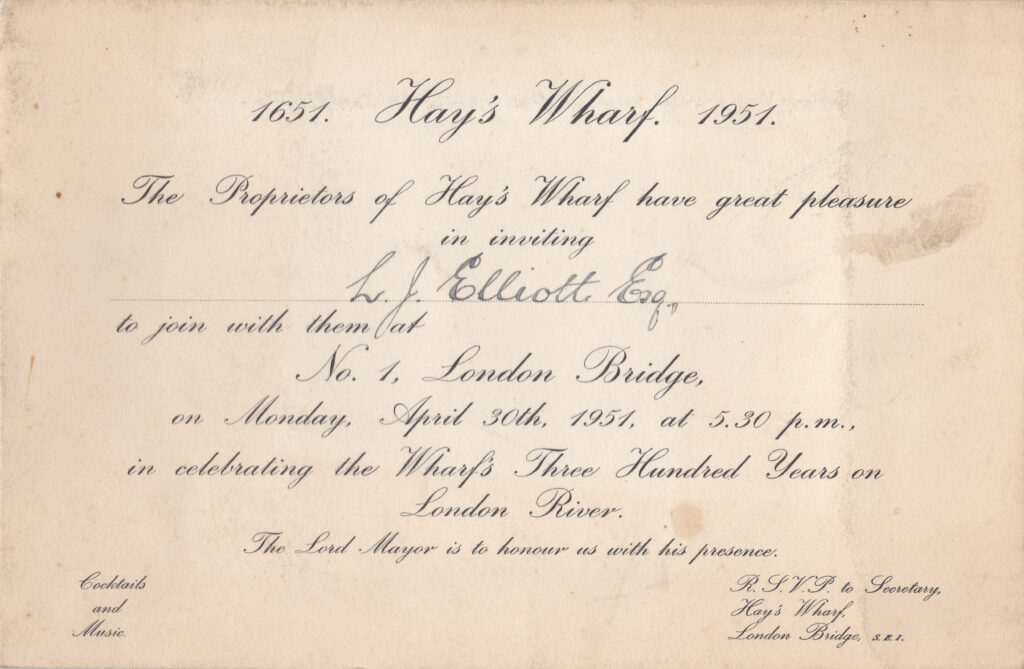

Seventy years ago, this coming Friday, at 5.30 p.m. on the 30th April 1951, Mr. L. Elliott Esq. arrived at No. 1, London Bridge to celebrate three hundred years of Hay’s Wharf. The Lord Mayor would also be attending and there were cocktails and music.

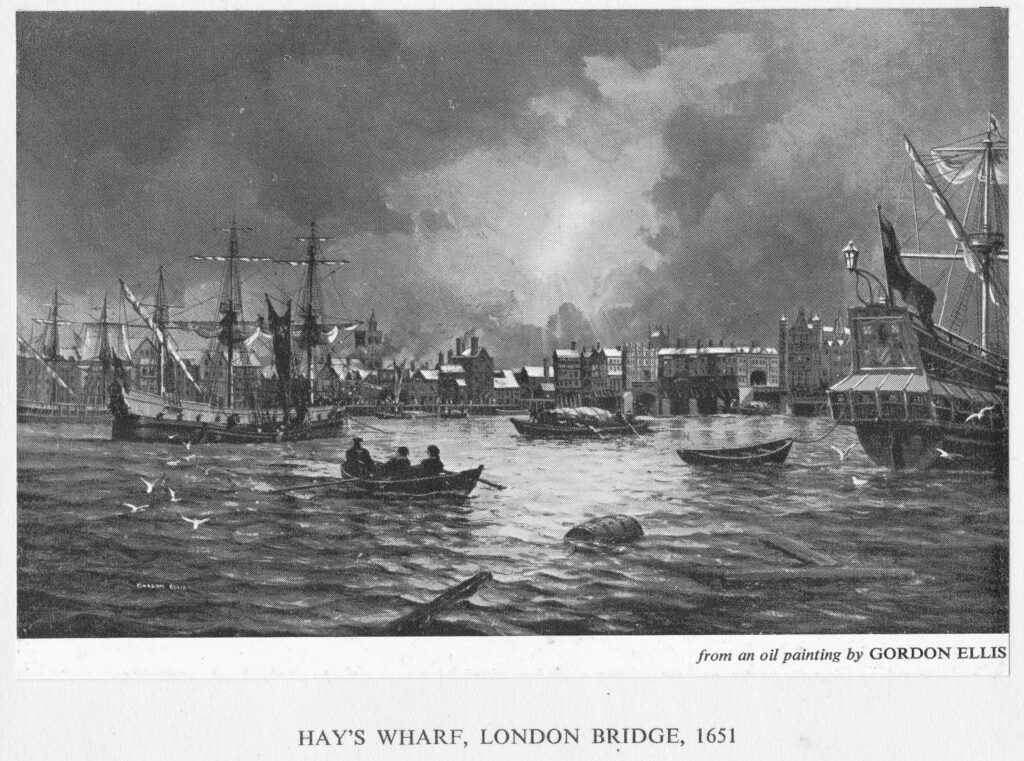

The invitation card pictured above opened out to reveal pictures from 1651 and 1951. The following picture shows Hay’s Wharf (with London Bridge on the right) in 1651:

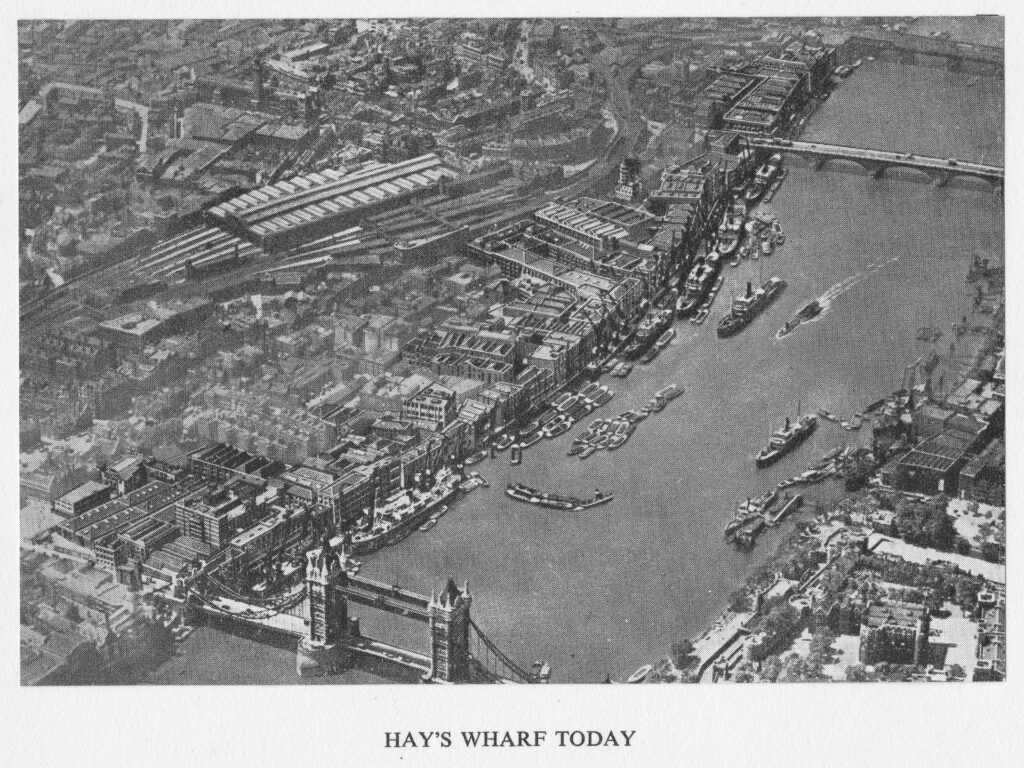

The second photo shows the wharfs occupied by the Hay’s Wharf company in 1951, running from London Bridge at top right, along the left side of the river down to Tower Bridge.

The edge of the river in 1951 appears to be a hive of activity with numerous barges, lighters and ships moored alongside the wharfs, and working in the river.

This was the Hay’s Wharf that the event on the 20th April 1951 was intended to celebrate.

Hay’s Wharf has a rather complicated history, with different owners of land, building and rebuilding of wharfs and warehouses, the Hay’s family, partners in the business and how Hay’s took over most of the river frontage between London and Tower Bridges.

Today’s post is an attempt to provide an overview of the 300 years of Hay’s Wharf and the Hay’s Wharf company.

The year 1651 as the founding of Hay’s Wharf seems to be year when Alexander Hay took over the lease of a brew-house from Robert Houghton, on the site of the current Hay’s Wharf buildings, alongside a small inlet from the river.

Running a brew-house may have meant that Hay realised the importance of clean water supplies. Water was being delivered to London by companies such as the New River Company, and by the London Bridge Waterworks, and these companies needed pipes through which to distribute their water.

Before a method of joining iron pipes was developed in 1785, water pipes were made from hollowed out tree trunks, and Hay set up a business to bore tree trunks and supply wooden pipes to companies such as the New River Company.

This was carried out at the small inlet at Hay’s Wharf, with buildings alongside constructed for the operation of the business.

Pipe boring must have been of such a scale that the Bridge House records, record Pipe Borers Wharf as the official name for Hay’s Wharf

There is one curious story of Hay’s Wharf during the early years of the 18th century. In 1709, the overall lease for the wharfs and properties close to London Bridge were taken over by Charles Cox who had been the MP for Southwark since 1695. It was from Charles Cox that Hay had an individual lease of the properties that formed Hay’s Wharf.

In 1697 the Treaty of Ryswick resulted in the persecution of Lutheran Protestants in parts of what is now Germany. Many of these fled to England as refugees and were granted an allowance of one shilling a day. Following early arrivals from Germany, numbers soon increased as news of the welcome they received in England spread. Numbers became such that there was a public outcry against the number arriving and the grant of a shilling a day. As a result, this grant was soon stopped.

Charles Cox announced that he would give asylum to all who arrived and would cover the cost. His approach to housing new arrivals was to crowd them into buildings at Hay’s Wharf and nearby Bridge House. Conditions grew very insanitary, and the local population were angered by the number of arrivals, and their living conditions so close to the existing residents.

Despite Charles Cox stating that he would fund the costs, the local Poor Rate had to be increased to £700.

Hundreds continued to arrive from Germany, and in desperation Charles Cox sent many to Southern Ireland, where they were not welcomed, and had to return to London.

Eventually, arrangements were made to ship the refugees to America, where they were settled in Carolina. It is interesting to wonder how many of those living in America today are descendants of those who travelled to America via the buildings at Hay’s Wharf and Bridge House.

Warehousing as a major business started from 1714 when the Customs Authorities allowed goods such as tobacco to be stored in warehouses on payment of a small percentage of the import duty.

If the product was then exported, the import duty would be repaid, allowing imported goods meant for export to be stored in warehouses tax free. Previous warehouses had been for the temporary storage of goods and the convenience of merchants, however tax free import followed by export significantly grew warehousing as a business.

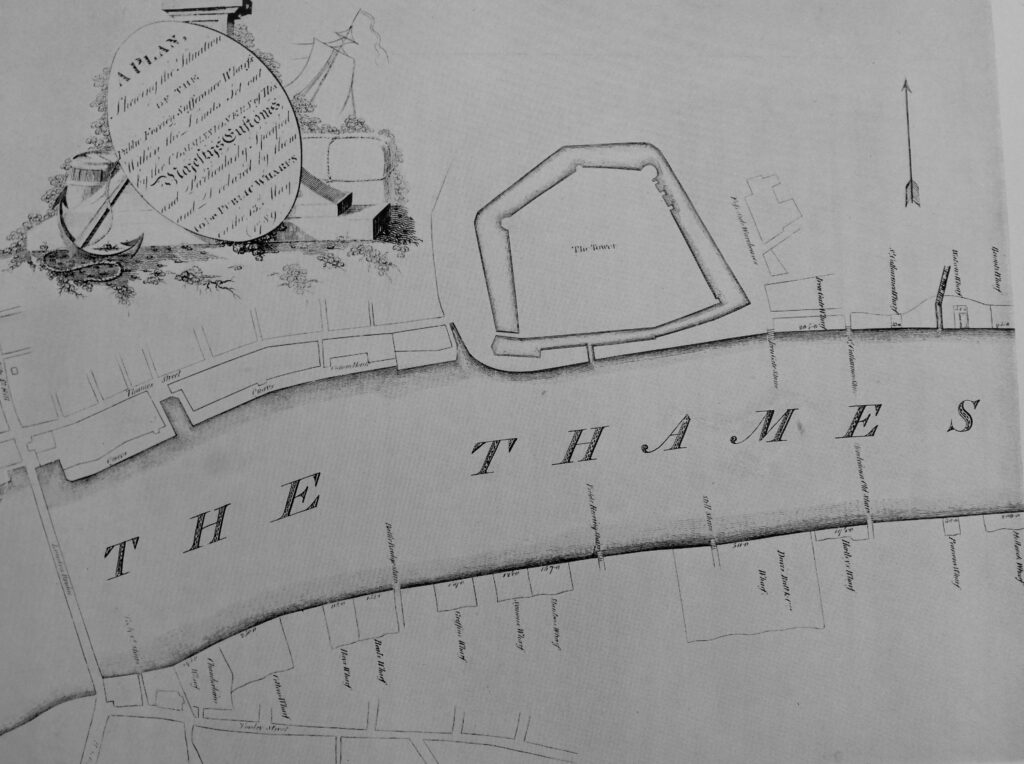

By 1789, Hay’s Wharf was just one of a number of sufferance wharfs along the south bank of the river. A sufferance wharf is one where goods can be stored until any tax or duty is paid.

The following map shows the sufferance wharfs lining the south bank of the river in 1789.

Hay’s Wharf was just one of a number that lined the river. From lower left are Chamberlain’s Wharf, Cotton’s Wharf, Hay’s Wharf, Beal’s Wharf, Griffin’s Wharf, Symon’s Wharf, Stanton’s Wharf, Davis Butt & Co Wharf, Hartley’s Wharf, Pearson’s Wharf and Holland’s Wharf.

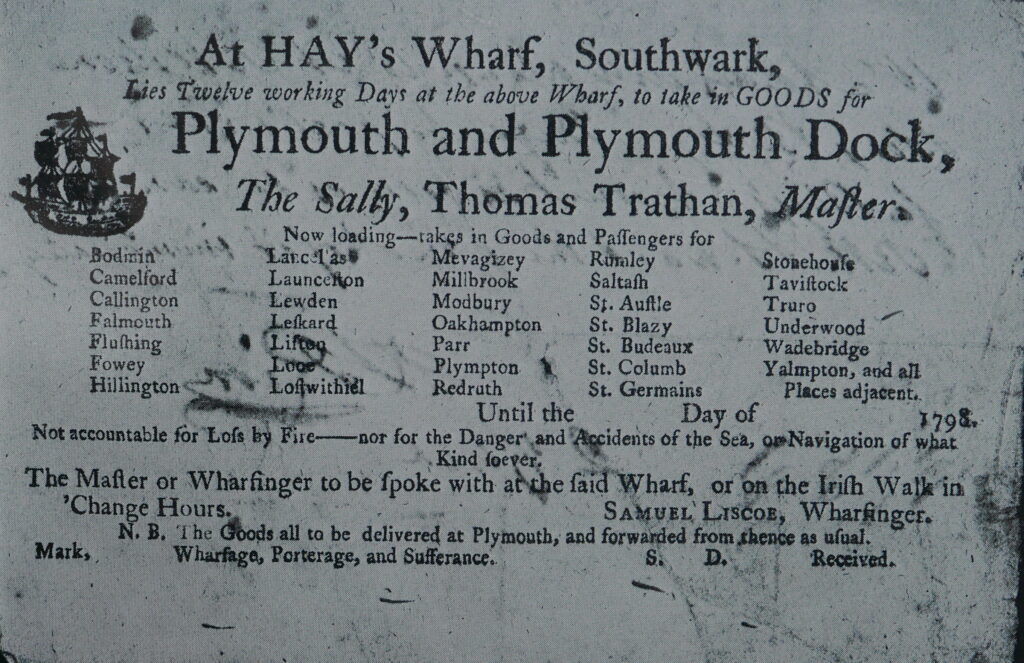

Hay’s Wharf was used as a place where ships would dock and receive goods and passengers for transport across the country, and abroad. A Hay’s Wharf sailing bill from 1798 provides an indication of how this trade was carried out.

The “Sally” would be sailing from Hay’s Wharf to Plymouth and Plymouth Dock, and the ship would be available for twelve working days at Hay’s Wharf to take goods for transport to Plymouth, from where they could then be forwarded to a range of locations in the West Country. As well as taking goods, the Sally would also carry passengers for Plymouth.

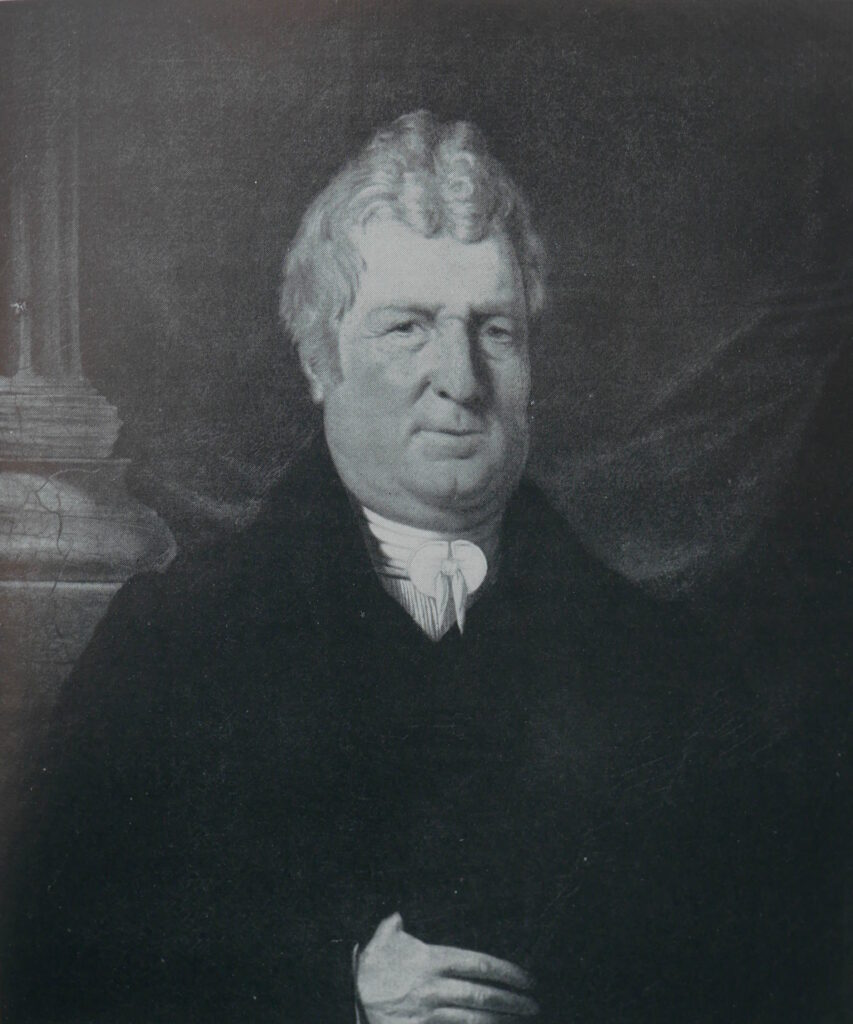

Throughout the 18th century, the Hay’s Wharf business had passed through the Hay’s family. Francis Theodore Hay would be the last of the family connected with the business.

Francis had been apprenticed as a Waterman before taking over the business. He would become Master of the Waterman’s Company and King’s Waterman to George III and George IV.

In the early 19th century, Hay’s business was seeing considerable competition. In earlier years the Customs Authority had granted sufferance, or the right to store goods without paying tax, to a limited number of wharf owners, however they now granted sufferance to any owner of land with a frontage on the river. Competition was also coming from the new docks which were being built east of the Tower of London.

Possibly because of this competition, Francis set up his son in a lighter building business, with a property on the river in Rotherhithe. Lighters were smaller, flat bottomed barges which allowed goods to be transferred from a ship, right up to the wharfs lining the river.

Francis Theodore Hay died in 1838, and was the last of the Hay’s connected with the wharf business. His son carried on running the lighter building business.

Francis Theodore Hay:

Francis Hay’s interest in the business seems to have been mainly financial, and Alderman John Humphrey (who already had a long association with Hay’s), now became the owner of the business. He would bring in two partners who were influential in the future success of Hay’s Wharf.

Hugh Colin Smith was a member of a family long connected with the City’s banking and commercial world. Arthur Magniac’s family was part of the Jardine, Matheson Company, one of the oldest Merchant Adventurers in China, and it was through Magniac that the tea trade was brought to Hay’s Wharf, with tea clippers from China bringing a high percentage of the tea consumed in London to Hay’s.

The trade with China was so successful that Jardine, Matheson referred to Hay’s Wharf as “our wharf in London”.

Humphrey, Smith and Magniac entered a fomal partnership in 1861 known as the “Proprietors of Hay’s Wharf”, although Humphrey would only live for another 18 months, however his sons took over their father’s interest in the partnership and Hay’s Wharf entered a period of considerable expansion and progress.

For the rest of the 19th century, and the early 20th century, Hay’s Wharf introduced mechanisation, purchased land and wharfs along the river between London and Tower Bridges, invested in new buildings and technologies such as a Cold Store. They also purchased the Pickford’s transport business.

It was during the early part of the 20th century that the Hay’s Wharf business was at the peak of its expansion and success.

The following painting by Gordon Ellis shows the tea clipper Flying Spur about to enter the dock at Hay’s Wharf on the 29th of September 1862. The ship is bringing the new season’s tea back from Foochow, China.

The site of the original Hay’s Wharf is now the Hay’s Galleria. Seen from across the Thames, two old warehouse buildings surround an open space covered by a glass and metal frame.

The central open space was once fully occupied by water, the remains of an old inlet from the river that had been turned into a dock so that ships could moor adjacent to the buildings that would store their cargo.

I cannot confirm the exact date of the current buildings. There are references to construction in 1856, however the 1861 fire, named in the press as the “Great Fire in Tooley Street” caused considerable damage to these buildings. The Morning Post of the 24th June 1861 describes the fire catching in the roof of Hay’s Wharf, tall columns of flame, the top floor blazing and the fire descending to the floor below, with the rest of the floors following.

The article described that this was supposed to be a fire proof building, and although it appears to have been considerably damaged by the fire, the fire did take longer to move from floor to floor than in the other warehouses.

Hay’s Wharf was repaired / rebuilt soon after, suffered bomb damage in the last war, and considerable restoration and modification at the end of the 20th century, which included the infill of the old central dock.

The following photo is looking along the interior of Hay’s Wharf, out towards the River Thames.

The following photo shows the interior when it was in use as a dock, with water running up to a narrow walkway alongside the building on either side (the walkway was a later addition to the warehouse buildings. When first built the dock ran directly up to the side of the building and to get between the different arches you would have had to walk through the interior).

The photo dates from 1921 and the ship in the photo is the Quest, the ship that the explorer Earnest Shackleton used for his final expedition to the Antarctic. Shackleton would suffer a fatal heart attack on the 5th of January 1922 whilst at South Georgia, where he would be buried.

The view back along the old dock from the river end of Hay’s Wharf:

The old entrance to the river can still be seen with the indent on the river wall and walkway:

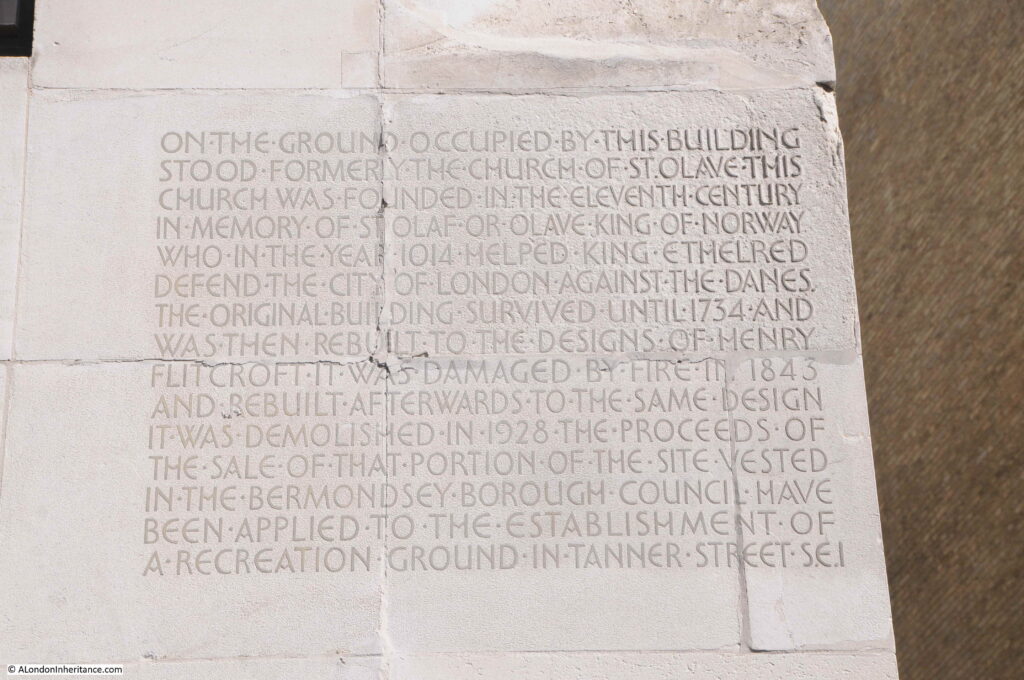

In the late 1920s, the Hay’s Wharf Company decided to build a new head office. This would occupy the site of St Olave’s Church, between Tooley Street and the Thames.

To continue a link with the 11th century saint after who the church was dedicated, the new head office would be called St Olaf House. The photo below shows the view of the building from Tooley Street:

St Olave’s church just survived the disastrous fire at Tooley Street in 1843. It was rebuilt the following year, however over the coming decades the size of the congregation declined, and in 1908 is was recorded that at one of the rare services at the church there were only five in the congregation.

The body of the church was eventually demolished with only the tower and graveyard remaining. In 1928, Bermondsey Borough Council proposed selling the church to the Hay’s Wharf Company in order to save public money. A bill was presented in Parliament to enable the sale, which requested permission:

“to sell to Hay’s Wharf the site of the Church of St Olave’s and the churchyard, comprising St Olave’s Garden between Tooley Street and the River, together with the right of demolition of the tower and the right to use the ground as a waiting place for vehicles, with loading bays, and to erect buildings upon it.“

The sale of the churchyard and the tower (a local landmark) was a contentious issue, but finally went ahead. The flagstaff from the tower was given to St George’s Church, Borough High Street and three bells from the tower were given to the Church of St Olave which was then being built in Mitcham.

The octagonal Portland stone turret, formerly capping the tower of the church was moved to the Tanner Street, Bermondsey park and children’s playground to form a drinking fountain. The playground was funded with some of the proceeds from the sale of the land.

The new head office was designed by H.S. Goodhart-Rendel and opened in 1931.

The Tooley Street entrance to the building is recessed under the building, with parking space and vehicle access between the entrance and Tooley Street.

The main entrance has the arms of the Smith, Humphrey and Magniac families above the door, along with the opening date of 1931. These three families were the partners in the company, and responsible for the considerable development and expansion of the company after 1862.

A black and gold mosaic of St Olave on the corner of the building:

On another corner of the building is recorded that it occupies the site of the church and the legend of St Olave:

Along with an award for the offices from the British Council:

View of the new Head Office from London Bridge:

The same view from London Bridge in 1951:

The focal point of the river facing side of the building is a large set of reliefs framing six of the windows:

The reliefs were the work of the sculptor Frank Dobson and completed using gilded faience (second time in the last few weeks I have come across this material. Faience is glazed pottery, see also post on Ibex House in the Minories).

The three large panels at the top represent Capital, Labour and Commerce, and the 36 vertical panels represent “The Chain of Distribution”.

Another example of Frank Dobson’s work can be found on the south bank of the river with “London Pride”, designed for the Festival of Britain, now outside the National Theatre.

Another 1951 view from London Bridge showing the head office, and the adjacent wharf (now the London Bridge Hospital). Note the cranes built on a pontoon in the river:

As well as the name of the building, the name of the saint and church continues with the name of the alley from Tooley Street to the river to the west of the building – St Olaf Stairs:

There are two interesting buildings just to the east of St Olaf House on Tooley Street. The photo below shows Emblem House, now part of London Bridge Hospital.

Emblem House was built in 1903 to a design by Charles Stanley Peach. Originally called Colonial House, the building was part of the change from wharfs and warehouses to commercial buildings along this stretch of Tooley Street.

In the photo above, there is a thin, brick built building to the left of Emblem House. This is Denmark House.

Built in 1908 to a design by S.D. Adshead, for the Bennet Steamship Company.

On the side of the building facing St Olaf House, at the very top of the building, there is a stone model of a steamship, with what looks like a funnel, two lifeboats and cranes at front and rear – possibly one of Bennet’s steamships.

After the war, some of the wharfs and warehouses lining the Thames between London and Tower Bridges were empty. Wartime damage and the transfer of trade to the docks east of the river had an impact, however there were still ships being loaded and unloaded at the wharfs owned by Hay’s Wharf. My father took the following photo in 1947 from in front of the Tower of London, looking across to the warehouses on the south bank of the river:

A ship is heading towards Tower Bridge, and a second ship is moored up against one of the warehouses, and cranes line the southern bank of the river.

This would not last for too much longer, and from the 1950s the business continued to decline.

By 1970, the Hay’s Wharf company was seen more as an owner of valuable property than a business running wharfs and warehouses. Following the release of the financial results for the company in 1970, newspaper reports commented that the results were “the London group owning 25 acres of prime Thames dockland, is almost as interesting as the takeover rumours surrounding the company”.

The Hay’s Wharf Company had announced a profit of £1.2 million, which “do not take into account the terminal costs on the closure of the Tooley Street wharves and expenditure on properties awaiting development”. The wharf and warehouse business had effectively closed by 1970.

There were various schemes proposed for redevelopment of the area between Tooley Street and the river during the 1970s and early 1980s. A 1981 scheme for a massive office development was the subject of a public enquiry, and in 1983 the Government gave approval for a scheme proposed by the London Docklands Development Corporation, which included a number of new office blocks, along with retention of a couple of the old warehouses, including Hay’s Wharf.

Hay’s Wharf reopened as Hay’s Galleria in 1987, with the old dock filled in.

View from the north bank of the Thames with Hay’s Wharf on the left, running up to London Bridge on the right.

The following photo shows Hay’s Wharf to the right, and the buildings running up to Tower Bridge on the left.

The majority of the above two photos was once part of the Hay’s Wharf Company. Today, the area is known as London Bridge City and is ultimately owned by the Kuwaiti Sovereign Wealth Fund.

I wonder what Mr. L. Elliott would have thought of what the area would become in the next seventy years, as he clutched his invitation and joined the celebrations of three hundred years of Hay’s Wharf.

To research this post, one of the key books I read is a book published to go with the 300 year celebration: “Three Hundred Years on London River – the Hay’s Wharf Story” by Aytoun Ellis. The book is a fascinating account of Hay’s Wharf, the development of this part of the south bank of the river, the families involved, and the commercial and political environment of London during those 300 years.

Worth noting that the Hay’s Galleria was part of London Bridge City Phase 1, masterminded by the British-founded but Kuwaiti-owned St Martins Property Corporation and mostly executed by Twigg, Brown & Partners. It combined new-build (Cottons Centre, No.1 London Bridge), restoration behind retained façades (Chamberlains Wharf, Emblem House, St Olaf House) and the transformation of Hay’s Dock, whose steel and glass roof was inspired by Milan’s Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II. A little-known tunnel connects each building and houses retail units.

The quote in your post ““the London group owning 25 acres of prime Thames dockland, is almost as interesting as the takeover rumours surrounding the company” is probably to the acquisition by the KIO (Kuwaiti Investment Office – the Kuwaiti government’s investment fund) of a 29.9% stake in the company (any more and they would have to have offered to takeover the company altogether). Eventually the company was 100% acquired by the KIO. Its extensive property interests were hived out into the KIO’s St Martins Property company, and the remainder of the company (a business process operator) was floated as Hays PLC.

The London Bridge Hospital (which occupies St Olaf’s House as well as the adjoining buildings) was originally established by the KIO to service Kuwaiti citizens, but was subsequently sold to HCA (one of the large private hospital operators).

But the Hay’s company has an interesting history beyond just owning the wharfs and warehouses along the south bank of the Thames. It had substantial warehousing, processing, and cargo related operations internationally. In terms of transport, it owned Pickfords (best known now as housemovers – but also a very long established business of road hauliers). Parts of the Hay’s business ended up being owned by the railway companies, and were nationalised with the railways in the 1940s. As an interesting sideline – Thomas Cook was taken into the ownership of the UK government during WW1 (as its owners – Wagon Lit – were an enemy business), and it was sold to Hays (the railway owned part of the business), and so it also ended up being nationalised in the 1940s.

Not quite so, Nicholas – the British assets were taken over by the government during WW2.

Interestingly, having been kept out of German hands during the war, the company was sold to a German bank in 1972.

The Proprietors of Hays Wharf was a UK listed company, so it would not have had its assets taken over by the Custodian of Enemy Property. To the contrary, Thomas Cook (which was owned by Wagon Lits) was sold by the Custodian to Hays Cartage Company (which by that point had become owned by the four railway companies).

However, during the course of WWII, the Government took over the effective management of the UK’s transport interests (which would have included some of the business interests of the Proprietors of Hays Wharf). But ownership of those assets remained with the original owners – although ultimately they would have been nationalised by the Atlee government.

The Proprietors of Hays Wharf remained a company listed on the London Stock Exchange until it was ultimately acquired 100% by the KIO. So I am not sure about your reference to it being sold to a German Bank in 1972. Are you referring to the purchase in 1992 of Thomas Cook by WestLB?

Yes. I was trying to avoid too much detail and in so doing made a keyboard slip.

Thanks for noticing.

I was a bit puzzled by ‘The British Council’ at first (it caught my eye because I worked for the BC for 30 years) and it had nothing to do with Hay’s Wharf that I know of. But in fact there is a little ‘for’ in front of ‘offices’ and this is an award from the British Council for Offices (BCO). The typography is pleasant, too – a tradition which the British Council once maintained but left behind in its gadarene rush to modernity, branding and typographic banality.

When I was an office boy in the late 1950’s, working for a import/export firm in Eastcheap in the City it was one of my jobs to collect packets of butter from the NZ Butter coy at Hays Wharf. This usually was Friday afternoons and the butter was bought at cost for the directors and seniors of our Coy. I was allowed one pack, on the way back across London Bridge I was walking against the crowds going home via London Bridge station, in hot weather the butter did get soft!

Just to add the final chapter on the St Olaf theme – until 1967 St Olave’s school occupied the land at the very end of Tooley St and the corner with Tower Bridge approach. A very upmarket Hotel now occupies the main buildings, but the playground and Eton Fives courts – yes in ‘Sarf London’ – are long gone.

lovely piece of digging! thank you. i wondered if there was a reason why Hay’s wharf was curved ?

Continuing the St Olaves Grammar School theme from Peter Barnett’s post, the school can be seen in the 1951 aerial photo on the left hand side about a quarter of the way up. The main building is visible together with part of the playground including the rather primitive lean-to toilet block, but the fives courts were further east just beyond the edge of the photo.

Very interesting, and photogenic, material. Absolutely up to the normal high standard. Many thanks. And some very interesting comments too, also as usual!

Thank you, that is so interesting. My Grandfather worked for Henry A. Lane and Co. Ltd of 37-45 Tooley Street. I have a booklet published in 1947, ‘A Record of Service’, which outlines the history of the company. There is a very good photograph of the Tooley Street office in it, also photos of all the staff and of Tanfield Place, West Clandon, to which many members were evacuated during the War. I believe the company was taken over by Swift and Co. of Chicago.

Very interesting. Thank you. An amazing history!

Your mention of “a method of joining iron pipes was developed in 1785” is spot on.

In that year, Sir Thomas Simpson, an engineer with the Chelsea Waterworks Company of London, invented the bell and spigot joint, which has been used extensively ever since. It represented marked improvement over the earliest cast iron pipe which used butt joints wrapped with metal bands and a later version which used flanges, a lead gasket and bolts.

Fascinating, beautifully written, and I particularly like the first photo of the ‘interior of Hay’s Wharf, out towards the River Thames’. It’s also really interesting to read the comments. Thank you.

For me, your most enjoyable and captivating article.

My grandfather was a wharfinger I think involved with Hays Wharf. He died in 1922 after meeting a ship in bad weather and getting pneumonia (SP?) His name was Frank Cecil Monk

I can only echo what has allready been said. Thanks you

Thank you so much once again for all the info and photos I have learntso much

Thank you for another fascinating piece about London’s history.

You mentioned Emblem House, originally Colonial House. Somewhere in the mists of my mind I recall that one of the UK’s largest grocery chains until 1961 – Home & Colonial – used the “Emblem” name for their own-label goods. I’ve not been able to research this to confirm so I am perfectly willing to be corrected.

I’m a great fan of your blogs and am currently researching the stretch of river along what was Pickled Herring Street – which you have covered in an earlier post.

An old map shows the various stairs and wharves and one name fascinates me – Dancing Bridge.

I haven’t been able to find anything out yet. Am aiming to get to Guildhall Library to do some digging but wondered if you had come across it in your research.

My family worked for Hay’s Wharf for years, on the lighterage side. I believe they were there in the late 19th C. When the lighterage business finished, my father was a tug captain and I think the lighterage business was named “Humphrey and Grey”? Although you mention Mr Humphrey, no mention is made of Mr Grey? I even have somewhere an enamel badge with the emblem H&G FC…the company had a sports ground for football and cricket at New Eltham. Going back further, one of my relatives was an officer on a tea clipper and that possibly docked at the wharf. We also have a forebear who became Mayor of London, Matthias Prime Lucas and since he had a lighterage apprenticeship in his youth, may have also worked for Humphrey and Grey.

Might anyone know how to find details of someone that was in charge of the place in the 1970’s? Thanks

The Hays Wharf company was acquired by the Kuwaiti Investment Office in 1980, and its assets realised in one way or another. The residual business was later floated as Hays PLC. The original Hays Wharf company still exists but has been renamed as Hays Holdings Limited, and you can inspect its annual reports online at https://find-and-update.company-information.service.gov.uk/company/00093338. The Companies House records also provide a list of all of its directors.

My father worked for Hay’s Wharf as a crane driver for over forty years and primarily worked at Hibernia Wharf which was still part of the Hay’s group which was located adjacent on the other side of London Bridge. He was one of a number of crane drivers to dip the jib of the crane for Winston Churchill’s funeral procession, I am guessing that it involved about sixteen cranes stretching along to Mark Brown’s wharf. Does anybody know the exact number?

I don’t know the exact number, but, I know I was late three days running to work by the streets being blocked for the funeral practice

My grandfather Owen Hugh Smith (d. 1956) was one of the last Smiths to work there. Son of Hugh Colin Smith (mentioned above), he spent much of his working life co-managing Hay’s Wharf, from which I think he must have done well. He became a substantial landowner, and in 1930 bought Ardtornish in Argyll, where I live.

Many years ago I read that Hay’s Wharf was notorious during the 1926 General Strike for the violent confrontations between striking dockers and their bosses. I’ve always meant to try to find out more, and am currently reading around the subject. If any one venturing upon this comment knows more, I’d love to hear it.

Thank you for your very good article.

The RIBA photo archive has some great photos of the construction and interior of St Olaf House:

https://www.ribapix.com/search?adv=false&cid=0&mid=0&vid=0&q=st%20olaf%20house&sid=false&isc=true&orderBy=0#

And I have a few on Flickr, some of which were originally taken for the ‘Thirties’ exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in 1979:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/royreed/albums/72177720305567134

As an Engineering Apprentice from 1961 to 1966, I must object to the caption regarding the cranes adjacent to St. Olaf house, ‘ cranes on pontoons’ those beast had an operating cab some 30 feet in the air with the jib extending another 70 feet. There would have had to be a heck of ballast on those pontoons to stabilize the weight, Those cranes ran on rails on a pier mounted apron, how else would the crane be allowed to lift from various holds or barges. just saying

What a marvellous history of Hays Wharf, thank you so much for collating it. My maternal Grandmother worked at Hays Wharf in her first job when she was probably around 14 or 15 years old; this would have been back in the 1920s I believe. For how long she remained in her job I do not know as all I have is anecdotal information from my mother; both women are now deceased. My Grandmother’s name at the time when she would have worked at the Wharf was Isabel Lillian Archer (she was always called Lily or Billie); she later became Mrs Eric Hudson on marriage. I recall being told that she used to work as a clerk and often took ‘trunk calls’, whatever they were. She was a true Cockney, born within the sound of Bow bells, but in what street I do not know. Our elders can impart such riches of memory if we choose to hear them; sadly, we often don’t have any interest in the past until we ourselves are growing older, by which time first hand information is no longer possible to obtain.

Is anyone aware of where the bodies that were buried in the St Olaves churchyard were moved to? I would assume they were moved, as it would be difficult to construct a building atop them without digging down. I have ancestors who were buried here and finding where they were moved to, or otherwise what happened to their remains, is difficult. I have read that they were moved to Potters Fields Park, Tooley St, closer to the Tower Bridge. I have also read they were interred at other locations and that other bodies are at Potters Fields Park. I also seemed to get A LOT of results for St Olaves Church north of the river, in Hart St. It’s difficult to find information on St Olaves church, Tooley street, and not Hart street. Any information, ideas, thoughts from anyone would be awesome!

My grandfather was a wharfinger I think involved with Hays Wharf. He died in 1922 after meeting a ship in bad weather and getting pneumonia (SP?) His name was Frank Cecil Monk