If you travel along Grosvenor Road, the road that runs along the Thames embankment in Pimlico, opposite Battersea Power Station, you may catch a glimpse of a tall, round tower between the blocks of flats that form the Churchill Gardens estate.

It looks rather out of place. An industrial construction within an area dedicated for residential housing. It is now 70 years old, and is the remains of an innovative solution to make use of waste heat from Battersea Power Station to warm the homes of those living on the opposite bank.

The tower is the most visible part of a highly complex system, that took hot water from Battersea Power Station, pumped it under the Thames through specially constructed pipes, stored water in the tower, then distributed it across both the Churchill Gardens and Dolphin Square estates for heating and hot water.

The system is described in considerable detail in a book published in 1951 for the Festival of Britain by the Association of Consulting Engineers. A large book that celebrates the work of civil engineering and construction across a wide range of projects.

The introductory paragraph to the section on the Churchill Gardens project provides an excellent description:

“In the ancient City of Westminster, almost within the shadow of the Houses of Parliament, so severely damaged by German bombers in 1942, great blocks of new flats are rising to meet the needs of London’s teeming millions, thousands of whom are still living in bomb-shattered houses built a century ago.

It is perhaps indicative of Britain’s will to survive and to surmount her economic troubles, that this great new housing estate, together with, it is expected an existing group of flats – probably the largest in Europe – is to have complete space heating and water heating by means of a district heating plan, thus banishing the dust and drudgery of the open coal fire, and the nuisance caused by the delivery and removal of fuel and ash for each block of flats. This plant is unique in two respects: it’s the first public heat supply in London, and it is also London’s first district heating plant wherein the heat is the byproduct of electricity generation. By this means the thermal efficiency of electric generating stations may be raised from its present figure of 25 per cent, to a figure approaching 75 per cent, for stations generating both electricity and heat.”

The section in the book is titled “District Heating Scheme, Pimlico Housing Estate and Dolphin Square”, as at the time the book was put together, the estate had not yet been given the name of Churchill Gardens.

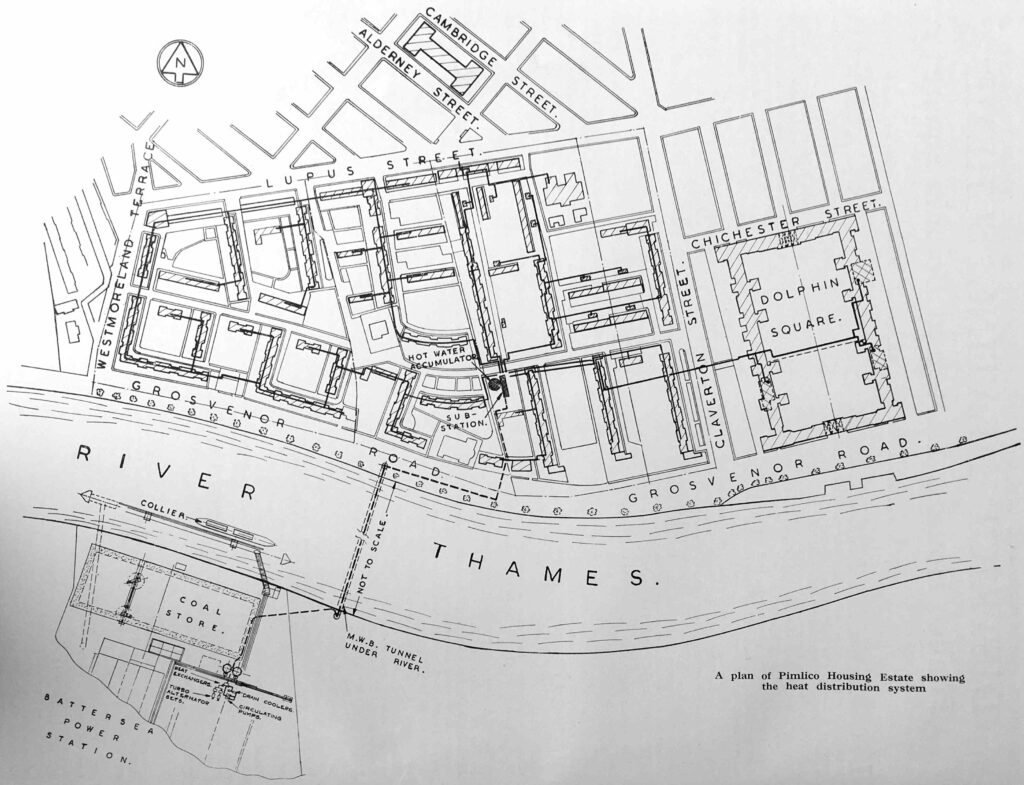

The book includes diagrams and photos of the project.

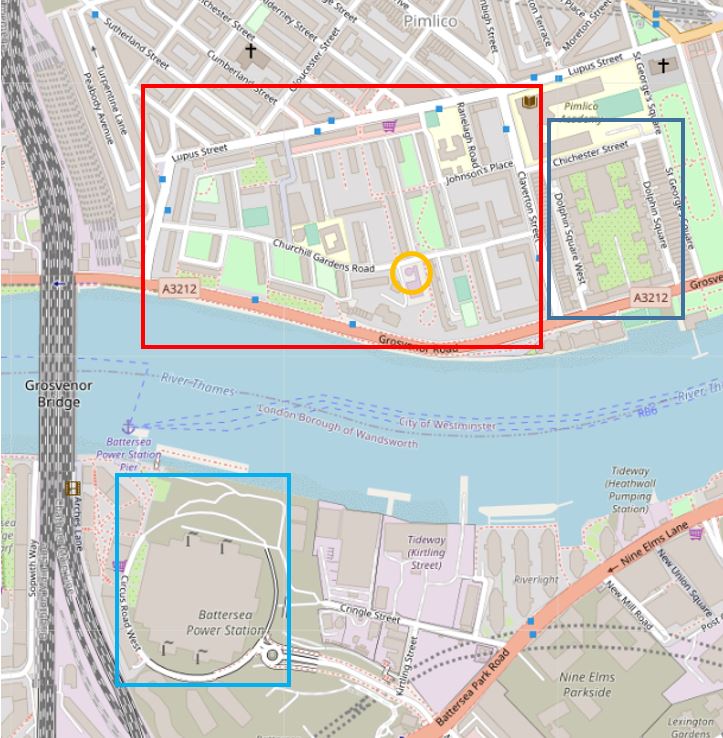

In the following diagram, we can see Battersea Power Station at lower left, pipes leading under the river to the Churchill Gardens estate which is bounded by Lupus Street, Claverton Street, Grosvenor Road, and Westmoreland Terrace on the western boundary (now an extension of Lupus Street).

In the lower centre of the estate is the tower, labelled as the “Hot Water Accumulator”. Dolphin Square, which also received hot water from the scheme is to the right.

The pipes under the Thames were installed in a pre-existing Metropolitan Water Board tunnel, and they consisted of 12 inch bore pipes for feeding water from Battersea and pipes for the return of water. They were insulated by being covered in 2 inches of compressed cork.

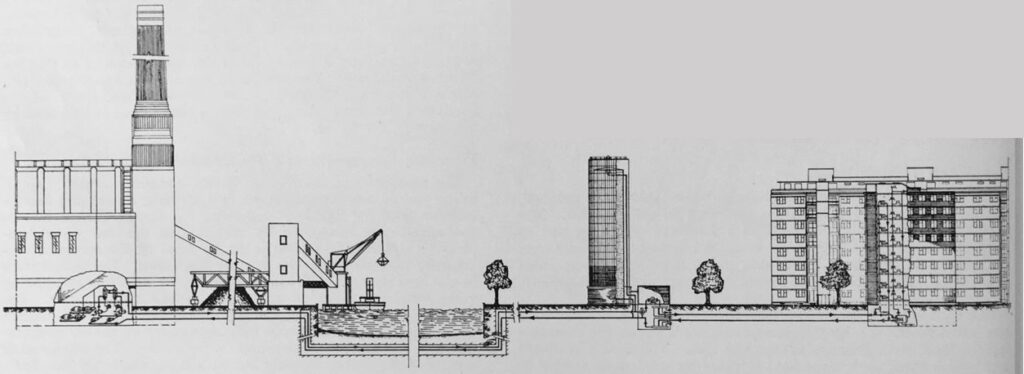

The water sent from Battersea Power Station was up to a maximum of 200 degrees Fahrenheit (93 degrees Celsius) and was stored in the tower, or to use its correct name, the “Hot Water Accumulator” before being distributed across the estate.

Hot water was fed directly to radiators for heating and to a calorifier for hot tap water (a calorifier is basically a coil of pipe inside a tank of water allowing heat to be transferred between the two, so water from the mains supply was delivered at the tap, rather than water from the power station).

The purpose of the tower was to store a sufficient supply of hot water to balance demand, for example when there was higher demand than could be provided immediately through the pipes under the river.

Water temperature was regulated by the injection of the cooler return water to the hot water as by the time water had been used to heat the estate and it was being pumped back to Battersea, it was 70 degrees Fahrenheit cooler then originally sent.

The following diagram shows the supply chain from power station to flats:

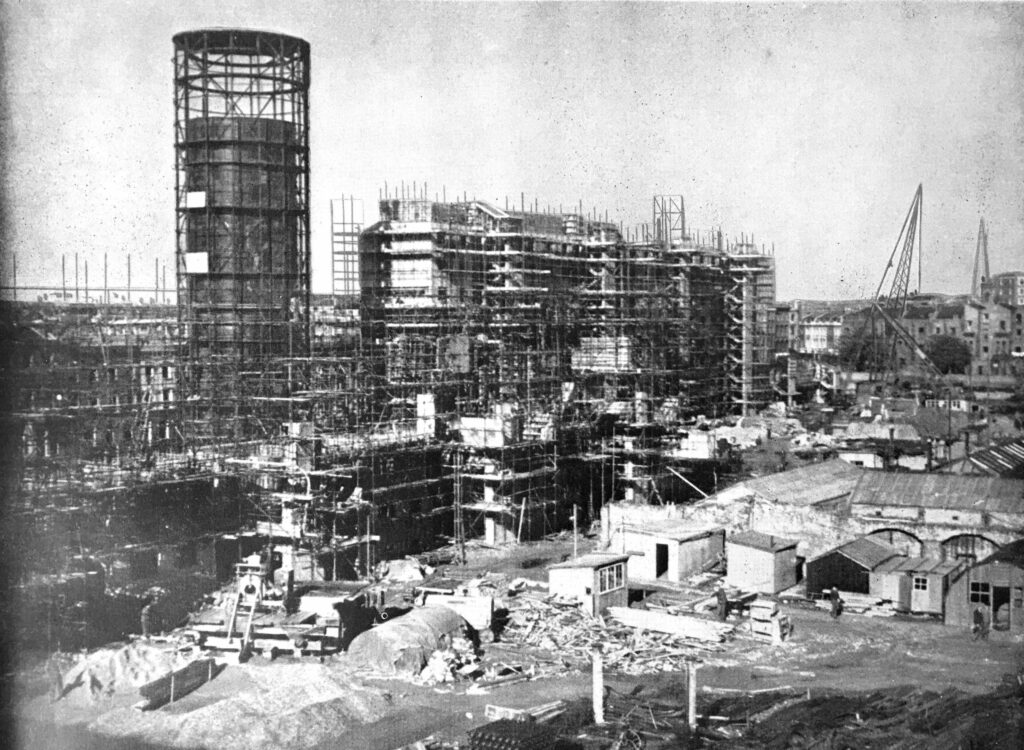

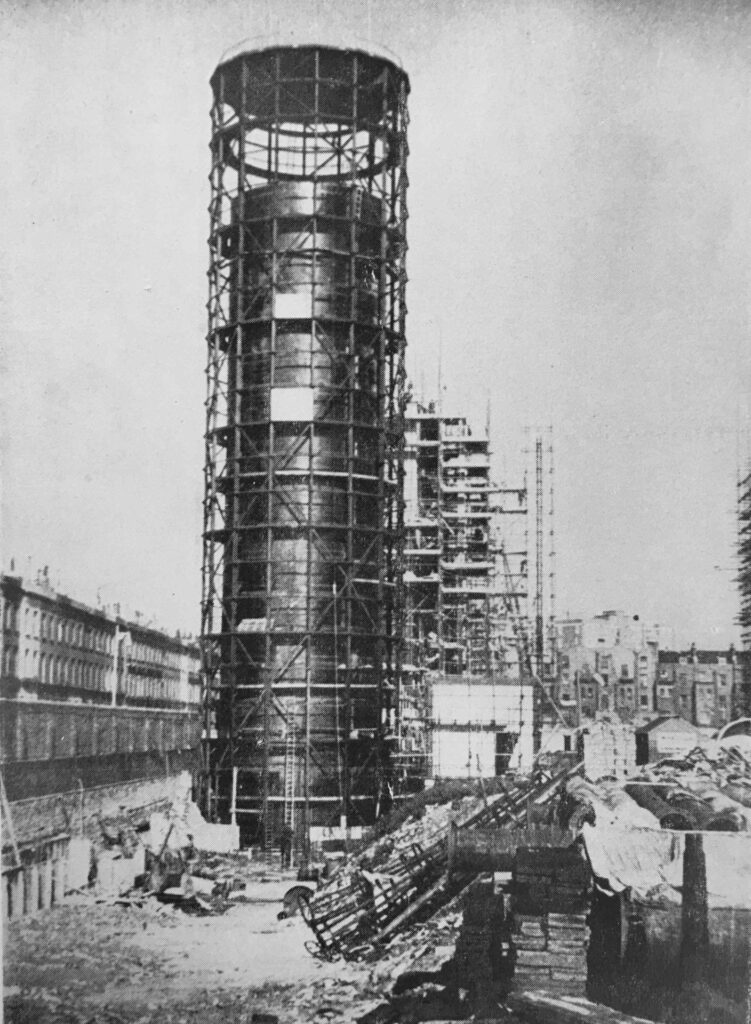

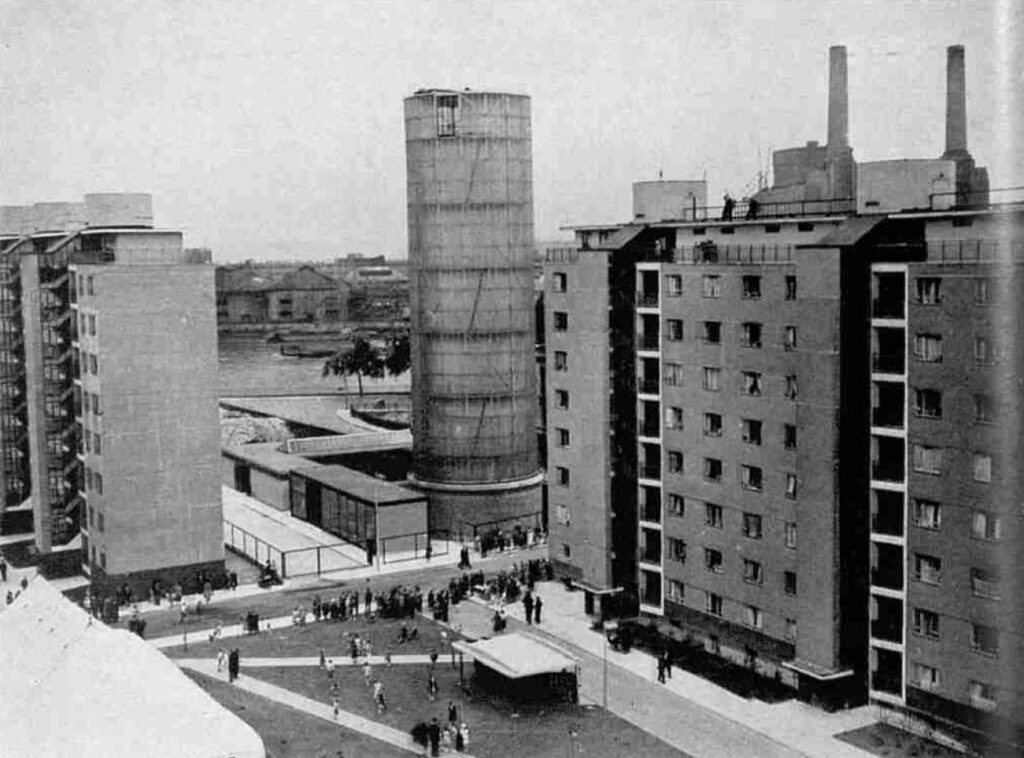

The hot water accumulator tower, along with the rest of the heating system was constructed at the same time as the rest of the Churchill Gardens estate:

The system had a number of safeguards built in as the Ministry of Health required assurance that the system would prevent the release of water at 200 degrees onto anyone who was working on the system. This included measures such as automatic stop valves which would operate when a fall in pressure was detected.

The outer surface of the tower consists of a steel framework with translucent glass panels.

Within the tower was the accumulator vessel which was 126 feet in height, and 29 feet in diameter. Constructed of mild steel plates and with a 3 inch layer of cork to provide insulation.

The project would save a considerable amount of coal, with the text in the book calculating a total of 10,000 tons of coal saved each year by taking the waste hot water from Battersea Power Station.

The amount of heat supplied to the individual flats across the estate was not measured, and a standard charge was applied to all residents for the service. For other buildings, the charge was based on the surface area of the installed radiators.

The hot water accumulator tower, and the first blocks of flats on the estate on the day of the official opening in 1951:

The following map shows the area today, with the Churchill Gardens estate within the red box, Dolphin Square with the blue box, and the hot water accumulator tower marked by the orange circle. Battersea Power Station is across the river marked by the light blue box (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

I went for a walk through the Churchill Gardens estate to find the accumulator tower and to take a look at the estate. Starting at the eastern side of the estate, I walked through the road that runs through the centre of the estate – Churchill Garden Road.

This is the view looking into the estate from Claverton Street:

Map of the estate at the entrance from Claverton Street:

Along with an early speed limit sign:

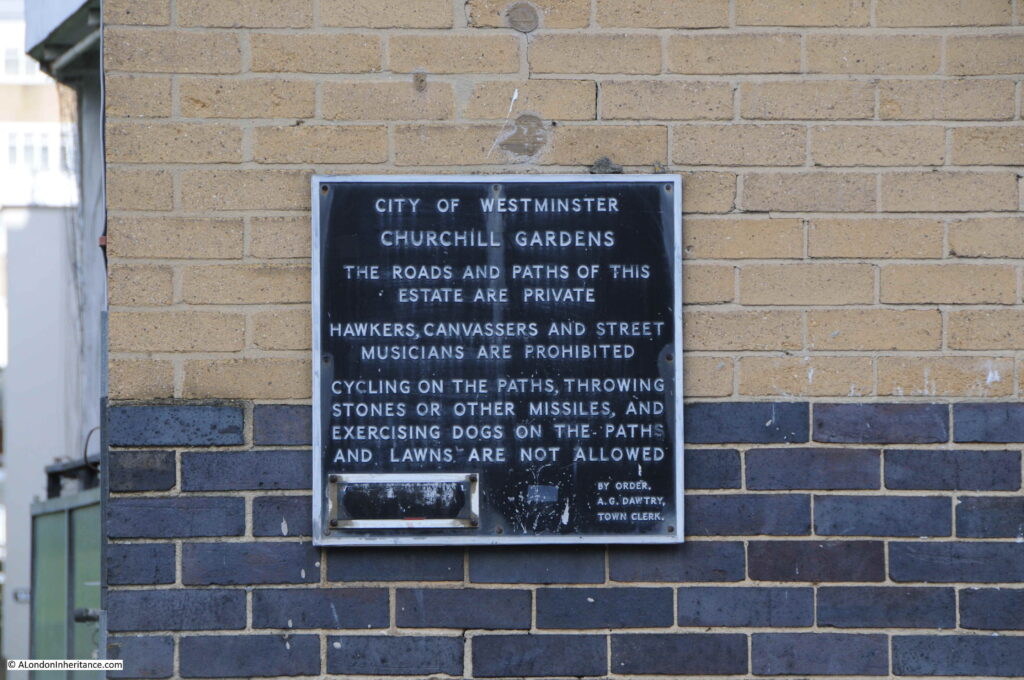

The A.G. Dawtry. Town Clerk mentioned on the speed limit sign was Sir Alan Dawtry, who was town clerk, then chief executive of Westminster City Council from 1956 to 1977. He lived for 61 years in the nearby Dolphin Square complex and was instrumental in saving the building when in the 1960s the company that owned Dolphin Square was going through financial problems, and there was a risk that the buildings would be sold off and converted to a hotel.

The above sign probably dates from the later part of the 1950s, as the estate was being completed.

Pre-war, the area occupied by the Churchill Gardens estate had consisted of industrial buildings and terrace houses. Bomb damage during the war, and the slum conditions of the housing meant that the area was ideal for redevelopment.

The 1943 County of London plan had proposed the development of large, well planned estates, and at the end of the war, Westminster City Council launched a competition for the design of a new estate.

The competition was won by Philip Powell and Hidalgo Moya, who were also responsible for the design of the Skylon for the Festival of Britain, the Queen Elizabeth Conference Centre in Westminster and the Museum of London building at London Wall.

The winning design by Powell and Moya included buildings with a variety of heights, consisting of eleven storey blocks to three and four storey houses and maisonettes. This was intended to break up any monotony across the estate, and to attract a broad cross section of residents.

Gardens and playgrounds would be provided between the buildings, and to address the urgent need for post war housing, the estate was designed to accommodate a high density of 200 people per acre, which was the maximum allowed at the time.

The first part of the estate that we reach from Claverton Street was the last finished. Built in the early 1960s, this part of the estate makes more use of glass than the rest of the estate:

One of these 1960 to 1962 blocks crosses Churchill Garden Road, almost creating the impression of a gateway to the rest of the estate:

Looking along Churchill Garden Road, we can see the main blocks of flats:

The road curves as it runs through the estate, so the main blocks of flats do not form a continuous wall along the road. They are also aligned north – south so as to maximise the amount of day light that would fall on their main east – west facing windows.

The blocks that were built during the first phase of construction, from 1946 up to 1951 have large, glazed stairways protruding from the sides of the blocks. Later blocks would have galleries running along the length of the blocks.

Well kept gardens between the blocks:

Shelley House with a glimpse of the hot water accumulator tower to the right:

In the above photo, a blue plaque can be seen on the wall.

Shelley House was one of the first four blocks completed by 1950 and the blue plaque is a Festival of Britain Award for Merit granted to these first blocks. These four blocks (Chaucer House, Coleridge House, Shelley House and Keats House) along with Gilbert House and Sullivan House on the western edge of estate, and the accumulator tower are also Grade II listed, and indeed the whole estate has been designated as a conservation area.

The Festival of Britain Award for Merit:

Looking back along Churchill Garden Road, and the block on the left has another plaque:

This plaque marks the official opening of the estate on the 24th July 1951 when the first phase of the estate, including the hot water accumulator tower, had been completed:

In the 1951 book by the Association of Consulting Engineers, the estate was called the “Pimlico Housing Estate”, as the estate had not yet been given an official name. A newspaper article in the Westminster and Pimlico News dated the 23rd March 1951 provides the sources of the name:

“It was disclosed at Westminster Council meeting that the name ‘Churchill Gardens’ was the brainwave of Housing Committee chairman, Councilor Miss Paton Walsh.

Mrs. Winston Churchill has agreed to perform the opening ceremony of the estate and of the district heating undertaking on Thursday, July 19.

Miss Paton Walsh pointed out that Mr. Churchill had many connections with Westminster in that he had lived and worked there and he was also their first honorary freeman of the city.”

The official opening covered the first phase of the estate and construction would continue into the 1960s. The 1950s were a difficult time for construction as there were so many competing demands for workers and materials as post war reconstruction gathered pace. This was also having an impact on Churchill Gardens as this article from the 3rd of August, 1951 edition of the Westminster and Pimlico News reported:

“Heartbreaking – It will be heartbreaking for home-seekers if flats at Churchill Gardens are held up while huge Government buildings started in the city are favoured and supplied with all the steel they need.

Sir Harold Webbe, Westminster’s MP attended the opening of Churchill Gardens. He is fully acquainted with the position. If there is a grave delay in the building of these flats he will undoubtedly use his influence in an effort to get things moving.”

Although the streets and houses that Churchill Gardens replaced had suffered bomb damage, with many regarded as slums, they were still occupied, and people were only moved when building had reached their part of the future estate. In 1959, contractors were preparing for demolition of the houses on the eastern edge of the estate ready for construction of the blocks that would be built in the early 1960s, however as the Westminster and Pimlico News reported on the 31st July 1959, there could still be delays:

“Demolition of houses in Claverton Street and Ranelagh Road, Pimlico on the site of Section IV of Churchill Gardens housing estate depends on rehousing the families still there.

Ald. C.P. Russell, chairman of the housing committee, said this at the Westminster Council meeting in a reply to a question put by Cllr. O.M. Boyd.

If rehousing proceeded at the anticipated rate, he expected demolition to start in the sprint of 1960.”

Another plaque from A.G. Dawtry. Town Clerk, this time banning Hawkers, Canvassers and Street Musicians, along with cycling on paths, throwing stones or other missiles, and that exercising dogs on the paths and lawns is not allowed.

It is at this point in the estate that we meet the hot water accumulator tower:

At the base of the accumulator tower are buildings that house equipment for the heating system.

The supply of hot water from Battersea Power Station ended in 1983, when the final generators at the power station closed.

The system supplying heat to Churchill Gardens was then converted to what we would now call as District Heat and Power system. In the buildings at the base of the accumulator tower are boilers along with heat and electricity generating systems which produce heat for distribution across the estate, along with electricity which is fed into the National Grid, which provides revenue to help subsidise the costs of the system.

A poor view through the fence into the equipment rooms at the base of the tower, along with a graphic of the tower on the glass:

The range of the system has extended from the original 1951 installation. As well as Churchill Gardens, the system now provides heating for Abbots Manor, Russell House and Lillington Gardens, with 5km of underground pipes serving 3,250 homes along with schools and commercial premises.

Another view of the equipment rooms, with the brick base of the hot water accumulator tower in the right:

When you get up close, you can see that the tower is built within a deep pit, the following photo shows part of the side walls to this pit:

These walls look as if they have some age, older than the Churchill Gardens estate, and their original purpose is rather surprising.

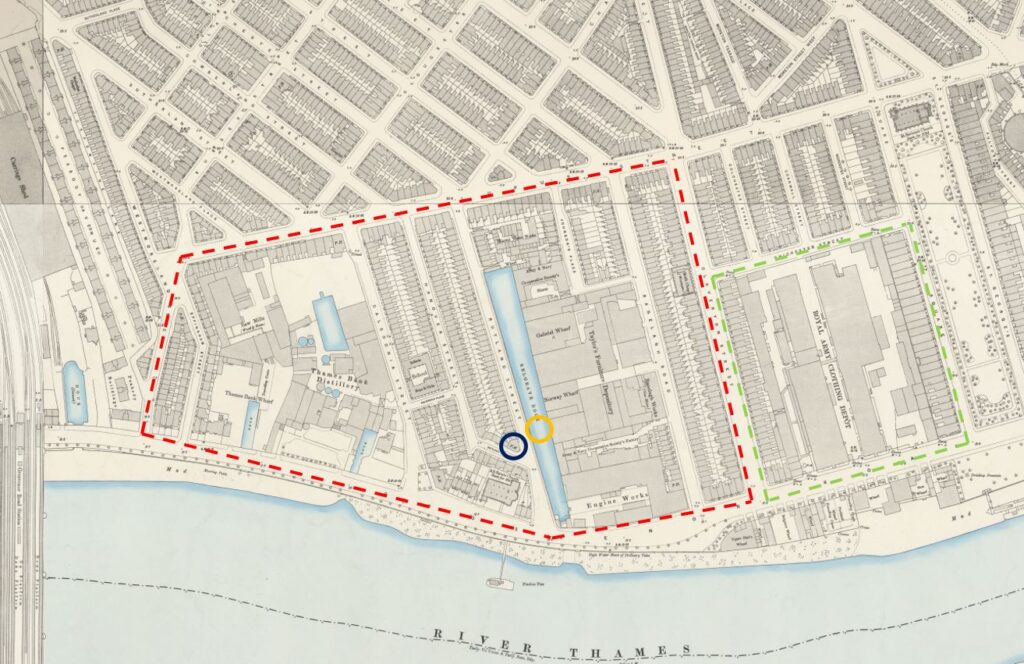

Before the war, there was a considerable amount of industry in the area now occupied by the Churchill Gardens estate. A distillery, saw mills, engine works and a furniture stores. There were also a number of wharves and docks, including one long dock called Belgrave Dock. This can be seen in the following extract from the 1894 Ordnance Survey Map (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’:

In the map, I have outlined the area occupied by Churchill Gardens in red and Dolphin Square in green. Note the difference in street layout between the area to the south of Lupus Street and the area to the north, which still remains much the same.

In the centre of the map is a long stretch of water – this is Belgrave Dock. I have marked the location of the hot water accumulator tower with the orange circle, and you can see that it stands in the middle of the dock.

The brick walls that can be seen in the pit next to the tower are the original surviving walls of Belgrave Dock. Rather amazing that these reminders of the areas industrial past survive.

Belgrave Dock seems to date from the early 19th century. The first written reference I can find is from the 26th February 1832 when the London News reported on a number of accidents during some of the very thick fogs that were covering parts of London at the time. As well as the Belgrave Dock, the report mentions the Grosvenor Canal, which was just to the left of the railway tracks on the left of the above map:

“FATAL ACCIDENTS DURING THE LATE FOG – Between eight and nine o’clock on Friday evening, a police constable discovered a woman in the Grosvenor-canal, Pimlico, quite dead: with assistance he got the body out, and conveyed it to the station-house, in Elizabeth street. The body was owned yesterday, and proved to be Mrs. Ann Hart, aged 72 years, residing in St George’s-row, near the wooden-bridge, Pimlico. There is no doubt that the poor old woman had, during the intense fog, walked into the Canal, which is very dangerous from its unguarded state, as she had her clogs on and a basket in her hand when found. She had merely gone out on an errand.

On Friday morning, john Dillon, a police-constable of the B. division, discovered the bodies of two men at the entrance of Belgrave Dock. They proved to be the bodies of Mr. Wilson, of No. 22, Prince-street, Lambeth, a wadding manufacturer, and his son-in-law, Mr. York; who it is supposed walked into the water during the fog.

The place is in a most dangerous state, particularly in foggy weather; and the only wonder is, that more accidents have not occurred. The place belongs to the Marquis of Westminster; and it is to be hoped that his Lordship will give immediate orders to have the evil remedied. We have heard that another female was brought out of the Canal yesterday morning.”

The report provides an impression of what the area was like in the early 19th century, and I like the address for poor Ann Hart as “near the wooden-bridge, Pimlico”.

Walking down the side road to the tower, and this is the view of the tower from the south:

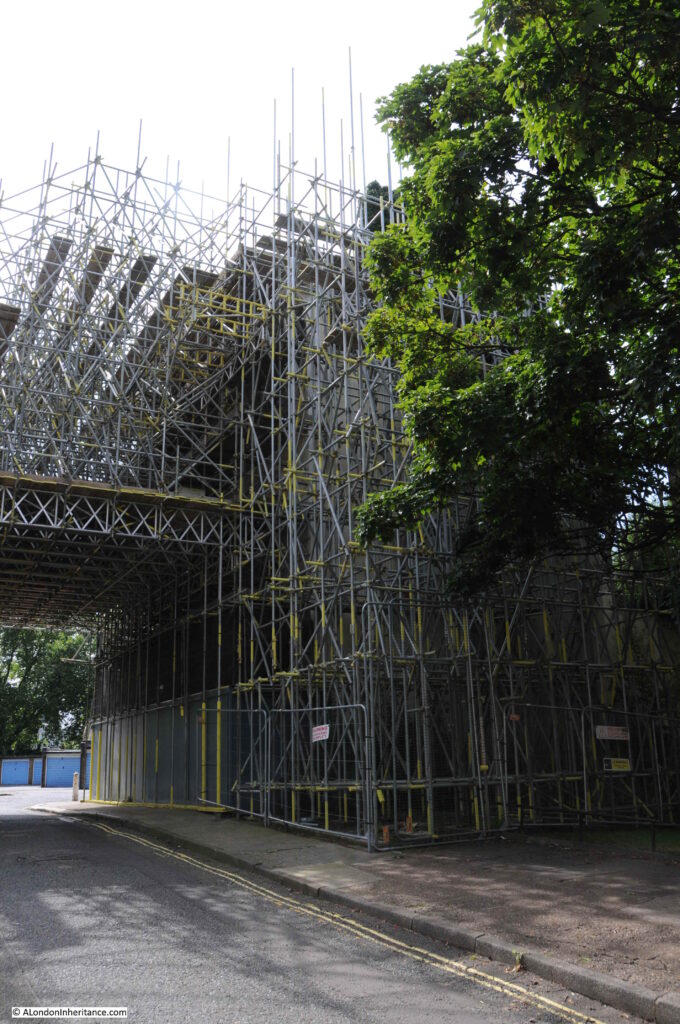

In the above photo, and in the photo below there is a large building completely covered in scaffolding, including scaffolding stretching across the road, presumably to provide some buttressing support to the building.

Buried underneath the scaffolding is a closed pub – the Balmoral Castle. A painted sign can just be seen on the side of the pub.

The Balmoral Castle dates from the mid 19th century and was part of the original development of the area. It can be seen in the 1894 Ordnance Survey extract above under the dark blue circle.

The pub seems to have been the focus for a number of sporting clubs, with the Metropolitan Cabdrivers Rowing Regatta and Mechanics’ United Rowing Club, along with the Pimlico Athletic Club all using the Balmoral Castle as their meeting place.

It was retained during the development of Churchill Gardens as the intention was to include community facilities for the residents. The pub closed in 2004, and the scaffolding was erected in 2014.

There have been plans to redevelop the area occupied by the pub and nearby Darwin House, but these do seem to be progressing rather slowly. In the meantime, part of the pub also seems to be supported by an incredible growth of what looks from a distance like a form of ivy.

Continuing along Churchill Garden Road, and we can see blocks built during later phases. These do not have the multiple external stairs, but have galleries along each floor.

There are design features such as concrete canopies over the entrances to the blocks:

As well as the Balmoral Castle pub, a school was retained during the construction of the estate. This is St. Gabriel’s Church of England Primary School.

The block of flats behind the school has the distinctive white rendered, rooftop drums for water tanks and lift equipment found on the top of the blocks across the estate.

At the end of Churchill Garden Road, I reached the western end of Lupus Street which forms the western boundary of the estate. The following photo is looking back through the estate:

We then walked along Grosvenor Road, along the Thames for another view of the hot water accumulator tower, with the scaffolding surrounding the Balmoral Castle to the left:

Part of the Churchill Gardens estate faces directly onto Grosvenor Road, however there are some original buildings that have survived:

One of which was another pub that has recently closed and is now being redeveloped. This was the King William IV, originally from the mid 19th century and rebuilt in 1880:

The future of the old pub seems to be some form of housing. The Health and Safety Executive Notification of Construction Project taped to one of the windows states that the address is now “Travel Joy Hostels Ltd” and the project will consist of 6 new apartments being designed and built, an extra floor added, and a basement to be constructed to the rear.

The old doors to the pub, with a gutted interior behind:

A short distance along Grosvenor Road is Dolphin Square. This large estate was also provided with heating from the original Battersea Power Station / Churchill Gardens system:

My original reason for exploring Churchill Gardens was to find the hot water accumulator tower, and there was one final part of the original system that I had to visit, and this was Battersea Power Station, which supplied the waste hot water across the river to heat the estate.

Battersea Power Station seen from across the river:

I also wanted to see how development of the old power station and the surrounding area was progressing. In the above photo, the large, glass apartment block that now sits between the power station and railway bridge can be seen on the right.

In the following photo, the additional building on top, and to the side of the power station can be seen:

Crossing the river on Chelsea Bridge, and the apparently random jumble of towers that are spreading along the side of the Thames in Vauxhall can be seen:

Battersea Power Station closed in 1983, and for many years the building was empty, roofless and derelict. After many false starts, much of the old building has been redeveloped. This included the complete reconstruction of the chimneys as the originals were structurally unsafe.

One of the chimneys is planned to included the Battersea Power Station Chimney Lift, which will lift visitors to the top of the tower to get a view from above. It is planned to open in 2022.

The redevelopment of the area follows the standard plan for any London developments – glass and steel apartments above, restaurants, cafes, shops and entertainment venues at ground level.

Alongside one of the new apartment blocks, restaurants, bars and a cinema have been built into the arches that line the railway viaduct:

From the Battersea side of the river, we can look across the river to the blocks of Churchill Gardens, and the hot water accumulator tower that was once supplied by the power station:

The new apartment block on the right closes in on the power station. There are restaurants on the ground floor and a small area of landscaping up to the river:

Looking between the power station and apartment building. A similar glass and steel building has yet to be built on the opposite side of the power station as the area links up with the tower blocks currently being built along Vauxhall.

The area behind and to the east of the power station is still blocked off for construction work, so there is not that much to see, apart from the area in front and around the new apartment building.

On a sunny Sunday, the cafes and restaurants seemed to be doing reasonably well.

The district heating system for the Churchill Gardens estate was the first of its type in London, and probably in the country. There have been a number of systems built since, the latest is the Bunhill 2 Energy Centre, built at the location of the long closed City Road underground station. Rather than waste heat from a power station, Bunhill 2 is unusual in that it takes heat from the Northern line tunnels below.

Bunhill 2 is an addition to the existing Bunhill energy centre built in 2012, which makes use of the more traditional gas powered engine to produce heat and generate electricity. The energy centre is open during this years Open House London event.

That was a rather long post, so thank you if you made it this far.

As usual there is so much to explore and discover. I find the combination of the hot water accumulator tower, built into the old Belgrave Dock, with the original side walls fascinating – relics of two very different industrial activities in Pimlico.

Churchill Gardens does have its problems, but is an estate that shows what can be done to provide housing with innovative design, well chosen materials, and importantly continuous maintenance of the buildings and landscape.

It was a fascinating walk.

Would be interested to know how the development is heated now? Thanks.

From Wikipedia – I suspect it’s fairly accurate:

“After Battersea Power Station closed in 1983, a 30MW coal-fired boiler was built to supply the system with heat. The boiler was subsequently converted to gas in 1989.[1] A refurbishment in 2006 saw two 1.55MWe CHP engines and three 8MW gas boilers installed.[2] The system generates around 51GWh of heat and 16GWh of electricity per year.”

A very interesting article, as usual. Wonderful start to a Sunday!

Thank you for finding and exploring features of the built landscape such as this water heating tower which would otherwise likely be overlooked. By your explaining both history and function, we readers come to understand far better how such a building comes to be there and its evolving service. It’s an awesome feat, thank you!

Another terrific trawl through an area of the city I need to be directed towards before I venture out to investigate solo. Your weekly features are addictive! They get me searching (your search feature is excellent, by the way) and I go off on a tangent (currently Old Ford Road – my student daughter just moved into Bethnal Green) and there’s another hour or so of my life well spent!

Thank you for broadening our awareness of so many interesting and potentially overlooked features of (probably) the best city in the world!

Thank you for this week’s article – it united both sides of my family ! One side from Battersea and closely involved with the power station and the other side from Pimlico. My grandfather was born in 8 Caledonia Street in 1879, next to the distillery and in the area covered by the estate. They were very poor and in one census 25 members of the extended family lived in part of the house. They seemed to flit between numbers 8 and 10 for thirty years. I did not know how dangerous the canal was and can now picture the area so well. Thank you.

Absolutely fascinating

Yes, a long posting but I made it to the end! That’s because it’s another fantastic piece of research into a part of London I knew as a young man but took at face value. It’s nice to know what I didn’t see all those years ago!

Thank you.

Yet again, marvellous research. Packed full of info. But I wonder if you are following me about as I was wandering round Churchill Gardens area last Sunday. All the best, and hope to see you again soon, Jane

Please never apologise for the length of your posts- the longer the better!

The considered arrangement of the buildings of Churchill Gardens (viewed from across the river) contrasts rather tellingly with the money driven mess both of the towers (from Chelsea Bridge) and the power station redevelopment.

“Before the war, there was a considerable amount of industry in the area now occupied by the Churchill Gardens estate. A distillery, saw mills, engine works and a furniture stores. There were also a number of wharves and docks, including one long dock called Belgrave Dock” Same almost everywhere along the Thames even after the war. It wasonly in the 70s or even early 80s that industry was comprehensively erased from the scene – the last warehouse in the City of London OPENED in 1972, for example (the structurally fascinating Fur Trade Huse south of St Paul’s).

In the 80s and much of the 90s I lived in Belgrave Road, close to Dolphin Square and the Churchill Gardens Estate. I read several times that the film “Passport to Pimlico” (released in 1949) was actually filmed in Pimlico itself, in bomb-damaged buildings. I have never known if this is true.

Hi Carole,

Although the film portrays fine attention to detail by employing a 24 bus (I’m sure you recall that route number from your Belgrave Road days) the externals were filmed in Lambeth. All delightfully detailed with “then” and “now” shots on the ReelStreets website:

https://www.reelstreets.com/films/passport-to-pimlico/

From a similar age the genuine Pimlico does feature in films such as “Stop Press Girl” and “Hunted”.

All the best

Pimlico Pete

Thank you! (I took the 24 bus to work regularly for years.)

Carole

it was filmed in lambeth not far from lambeth walk

Fascinating Article as usual. My Mother in Law lived in adjacent St Georges Square in the 1960s and the locals were always ambivalent about the Dolphin Square heating system next door. I recall there were new school buildings at the north east edge of the area, and the roofs were “all glass” and there was a lot of grumbling about “overheating”. The visionary scale of the project at the time has to be admired. There is a 1965 film called “Four in the Morning” starring a young Judy Dench which shows very moodily in black & white riverside shoreline sequences played out in this area and creates a good atmosphere of what life was like 50 odd years ago. May thanks for your time and effort.

Another wonderful and interesting article with memories for me of Battersea power station at work as seen from my first work office in Vauxhall Bridge Road in the early 1960s, the Funfair from the Festival of Britain years, The Lister Hospital and Lopus Street. One of the two pictures of the construction also show “Derrick Cranes” in the background as advised to me in a comment I made on the Angel post seeking pictures of crane construction methods. A second picture shows construction access at height using what appears to be a lift with access floors to each storey. Any web references to other buildings under construction in the 1930 to 1950 period would be of interest.

Fabulous article. An area I often walk around. Have never actually noticed the heating tower! Thank you so much. I can’t wait for the Thames footpath to be fully opened on the Battersea side. Am not sure how I feel about the flats around the power station. Just very grateful the Battersea Power Station is still standing in all its glory.

I found this really interesting thank you.

Fascinating! Thank you as always for sharing your photos and research.

Brought back great memories, thanks. Churchill Gardens was one of my ‘beats’ during the 70s when I was a Pc at Rochester Row Police Station

As always a superb pice of work, well done and thank you. I particularily enjoyed this as I work in the M&E industry, really fascinating to learn about the tower.

More please…

The accumulator tower was featured in the 1953 film Genevieve.

Any plans to do a walk in this area including Battersea Power Station?

Thanks so much for a fascinating article, thoroughly researched as ever. You can feel the sense of urgency and optimism in those post-war estates. The survival of the old dock wall is intriguing – I’d no idea that dock existed, let alone its grisly history during the notorious London fogs.

Great stuff for curious Londoners.

Once again, a most informative read for those of us who love the City and live very far away. Having visited London over15 times since 1973, I like to find out about and explore places that are unusual and not always on the tourist trail. Long may your contributions continue.

Thank you for this comprehensive blog, Enjoyed your writings and inclusion of the map before Churchill Gardens & Dolphin Square existed. Resided in St Georges Square (East side of this map from 1966- 1972 or so.

Great post, thank you.

I look forward to and really do enjoy reading your weekly blogs and this week was a real treat. I have been hoping that one day you would get round to covering this location and bingo you did. I have been researching the adjacent area directly to the right of the 1894 map for the last three years. You can just make out the gasometer outlined in the top right hand corner of the map. My work so far links together Post war movies, Millbank Prison, Building the Houses of Parliament, Cody Guns and Dickens with an address at No 77 Grosvenor Road. The address also made models of the Skylon for the 1951 fair. If you are interested you are more than welcome to a copy.

Hi Colin – that sounds an interesting project! It would be great if you could publish it somewhere.

Good luck

Mike

Fabulous, in depth article!

Thank you.

I have only just joined your website. Excellent! Do you have walks that one can join?

Carol

Been away for a couple of weeks just caught up with this blog very welcome indeed .

When I was younger and the international borders were open, I would stay at the hostel in the King William when I was in London. It had incredibly small staircases, the bathrooms were kind of dodgy, and the rooms could not physically have fit any more bunk beds, but there was nothing like waking up on a summer morning and looking out the window to the Thames and Battersea. Only afterwards did I develop my interest in modern architecture and realise what a gem the estate was… Lovely piece of writing! Thank you!

Battersea Power Station was the “temple of power”and now it is been converted into the “temple of technology”.With around 3000 Apple employees going to work in the former power station and with the new Northern line extension to Battersea it is a trip I look forward to.

I’m living in Churchill Gardens now and much enjoyed this post. I’m having a look online to see what I can find as I’m interested in just how successful the heating system was (taking hot water from Battersea Power Station), from the point of view of residents. Your post partly answers the question. If it remained in place from 1951 to 1983 – 30+ years – then that says something about its success.

Today, as you say, the estate and others around it are still heated from one source. It works pretty well, I’d say. We get a lot of heat through the radiators most of the day.

Interesting also to note that the heating system went into operation one year before the Clean Air Act 1952 to combat London’s killer smogs, thus admirably preceding the legislation.

Such an interesting article! I knew that there was a communal heating system there – and many of the flats are local authority owned (some now private ownership). I have been thinking about how visionary the designers were when this was built. As I write this (Feb 2022) there is an energy crisis where increasingly high energy bills are making some low income families chose between heating and eating. Presumably this would not be a problem for the residents in the local authority owned flats at Churchill Gardens as all their heating and hot water would be paid by the local authority (but private flat owners do pay). I wonder if the cost per flat of heating and hot water is more economical on a big estate, compared with having an individual boiler in each flat? Thanks again – interesting read.

Thank you for a very interesting article.

I grew up, during the ’50s and ’60, living in Coleridge House; the photo of the accumulator with the power station in the distance was very much the view from my bedroom for 20 years.

I’d heard there used to be a “canal” behind Chaucer House but (pre internet) I had no other info. I always thought the strip of grass behind Chaucer House may be all that was left; I’m ashamed to say I’d never noticed the brickwork of the dock that you highlighted.

What you didn’t see were the great playgrounds where the equipment has now been replaced with “something safer”. For example one playground had a castle complete with chain bridge and spiral staircase, as well as a real steamroller that we could climb all over. This later I see was sold and refurbished as the “Churchill” and exhibited at steam rallies.

Happy times!

Amazing to read this article as I moved onto the estate in 1957 aged 3 and lived there until the age of 17yrs. We first lived in Maitland house, a 2 bedroom maisonette, then moving to Littleton house, a 3 bedroom maisonette when I was11yrs as I had a brother by then and we weren’t allowed to share a bedroom. I remember all the different flats, one bedroom, 2 & 3 bedroom flats, bedsits and maisonettes. Certainly catered for all needs. I had a great childhood attending St. Gabriel’s primary school, playing outside all the time and as previously mentioned the playgrounds were an adventure. I feel sad now that my Grandsons will never experience the freedom we had growing up on this estate.

Enjoyed reading this. Brought back lots of memories. My first job in London after University in Bristol was as a temp at the technical department of the Estate Office at then of 1984 or early 1985. The basement had large cabinets with big architectural drawings and plans of the area and different stages of development through the decades. I was told about the hot water tower by the chief technical officer. I believe they called it the PDHU, Pimlico District Heating Unit, or maybe that’s what replaced it. I remember thinking at the time, what a great idea to recycle waste water from the power station, which as you say, in 1983, they must have just stopped doing.

I must have missed this post or it was before I subscribed. I also lived in Churchill Gardens from 1961 to 1986. Thanks for a great read. Have you seen the brief film made by Ian Nairn about the estate I think in the 1960s. Worth a watch on YouTube. I can tell you that when my mum and dad moved in there from The Ebury Bridge Road Estate, they very much appreciated the warmth provided by radiators especially the winter following of 62/63!

it was filmed in lambeth not far from lambeth walk

A fascinating article, made more so as I was born across the road from the final stage of Churchill Gardens Estate, at 50 Claverton Street. We lived in the basement flat of the building, now more grandly known as the “garden flat”.

The building was then divided into bedsits and my father was the caretaker, so we had more room.

My brother and I would sit on the main steps of the building watching the construction going on over the road. We would have been about four and six respectively. I actually have a photo of us sat there.

Additional to my last comment (December 3, 2023 at 10:34 am):

My family also lived on the estate in Whitley House, from 1972 until 2017.

Hello,

The image links appear to be corrupted?

Gordon

Thanks – seems to be a problem which the hosting provider is aware of.