If you travel along Grosvenor Road, the road that runs along the Thames embankment in Pimlico, opposite Battersea Power Station, you may catch a glimpse of a tall, round tower between the blocks of flats that form the Churchill Gardens estate.

It looks rather out of place. An industrial construction within an area dedicated for residential housing. It is now 70 years old, and is the remains of an innovative solution to make use of waste heat from Battersea Power Station to warm the homes of those living on the opposite bank.

The tower is the most visible part of a highly complex system, that took hot water from Battersea Power Station, pumped it under the Thames through specially constructed pipes, stored water in the tower, then distributed it across both the Churchill Gardens and Dolphin Square estates for heating and hot water.

The system is described in considerable detail in a book published in 1951 for the Festival of Britain by the Association of Consulting Engineers. A large book that celebrates the work of civil engineering and construction across a wide range of projects.

The introductory paragraph to the section on the Churchill Gardens project provides an excellent description:

“In the ancient City of Westminster, almost within the shadow of the Houses of Parliament, so severely damaged by German bombers in 1942, great blocks of new flats are rising to meet the needs of London’s teeming millions, thousands of whom are still living in bomb-shattered houses built a century ago.

It is perhaps indicative of Britain’s will to survive and to surmount her economic troubles, that this great new housing estate, together with, it is expected an existing group of flats – probably the largest in Europe – is to have complete space heating and water heating by means of a district heating plan, thus banishing the dust and drudgery of the open coal fire, and the nuisance caused by the delivery and removal of fuel and ash for each block of flats. This plant is unique in two respects: it’s the first public heat supply in London, and it is also London’s first district heating plant wherein the heat is the byproduct of electricity generation. By this means the thermal efficiency of electric generating stations may be raised from its present figure of 25 per cent, to a figure approaching 75 per cent, for stations generating both electricity and heat.”

The section in the book is titled “District Heating Scheme, Pimlico Housing Estate and Dolphin Square”, as at the time the book was put together, the estate had not yet been given the name of Churchill Gardens.

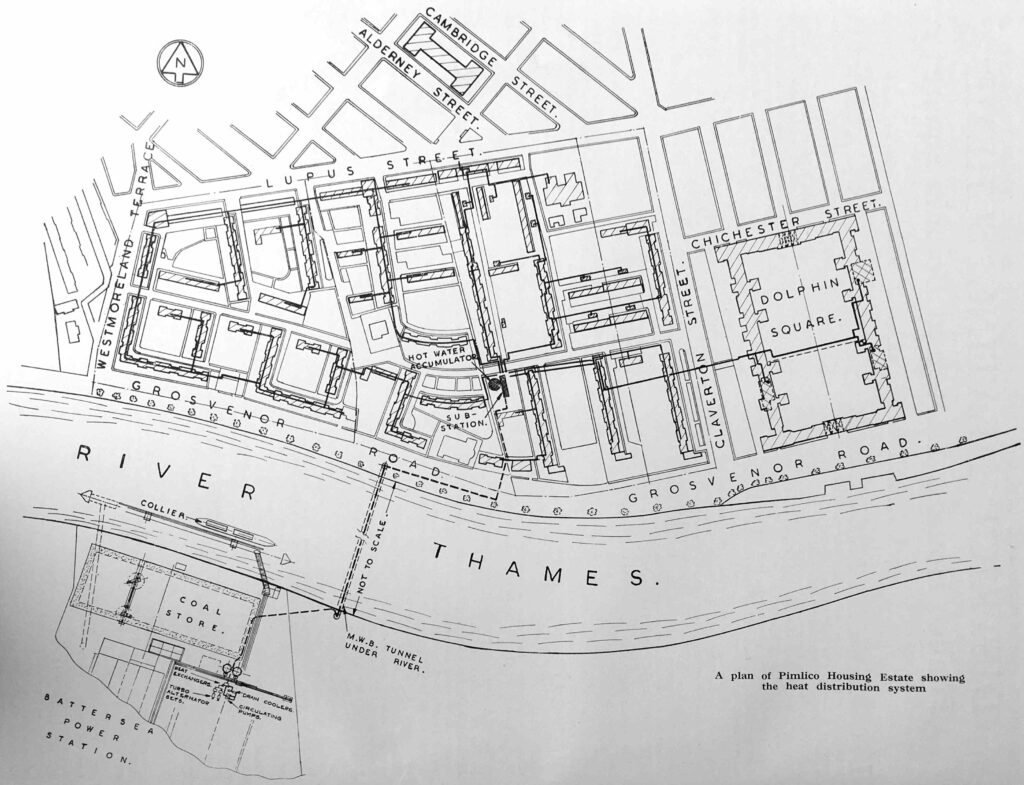

The book includes diagrams and photos of the project.

In the following diagram, we can see Battersea Power Station at lower left, pipes leading under the river to the Churchill Gardens estate which is bounded by Lupus Street, Claverton Street, Grosvenor Road, and Westmoreland Terrace on the western boundary (now an extension of Lupus Street).

In the lower centre of the estate is the tower, labelled as the “Hot Water Accumulator”. Dolphin Square, which also received hot water from the scheme is to the right.

The pipes under the Thames were installed in a pre-existing Metropolitan Water Board tunnel, and they consisted of 12 inch bore pipes for feeding water from Battersea and pipes for the return of water. They were insulated by being covered in 2 inches of compressed cork.

The water sent from Battersea Power Station was up to a maximum of 200 degrees Fahrenheit (93 degrees Celsius) and was stored in the tower, or to use its correct name, the “Hot Water Accumulator” before being distributed across the estate.

Hot water was fed directly to radiators for heating and to a calorifier for hot tap water (a calorifier is basically a coil of pipe inside a tank of water allowing heat to be transferred between the two, so water from the mains supply was delivered at the tap, rather than water from the power station).

The purpose of the tower was to store a sufficient supply of hot water to balance demand, for example when there was higher demand than could be provided immediately through the pipes under the river.

Water temperature was regulated by the injection of the cooler return water to the hot water as by the time water had been used to heat the estate and it was being pumped back to Battersea, it was 70 degrees Fahrenheit cooler then originally sent.

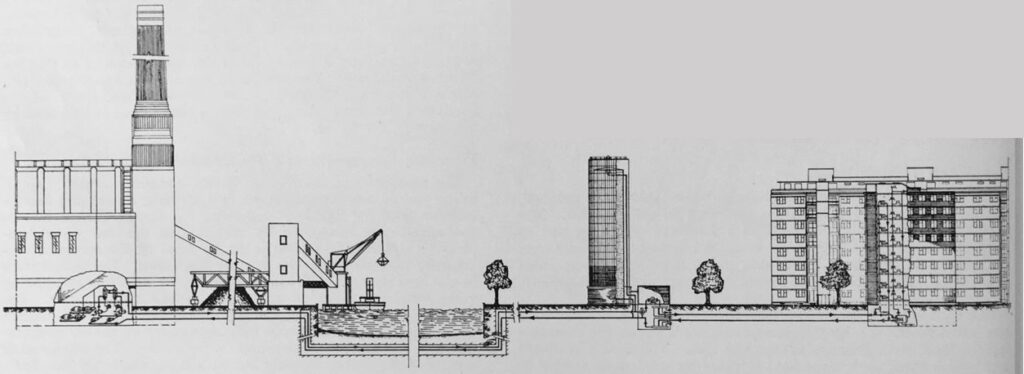

The following diagram shows the supply chain from power station to flats:

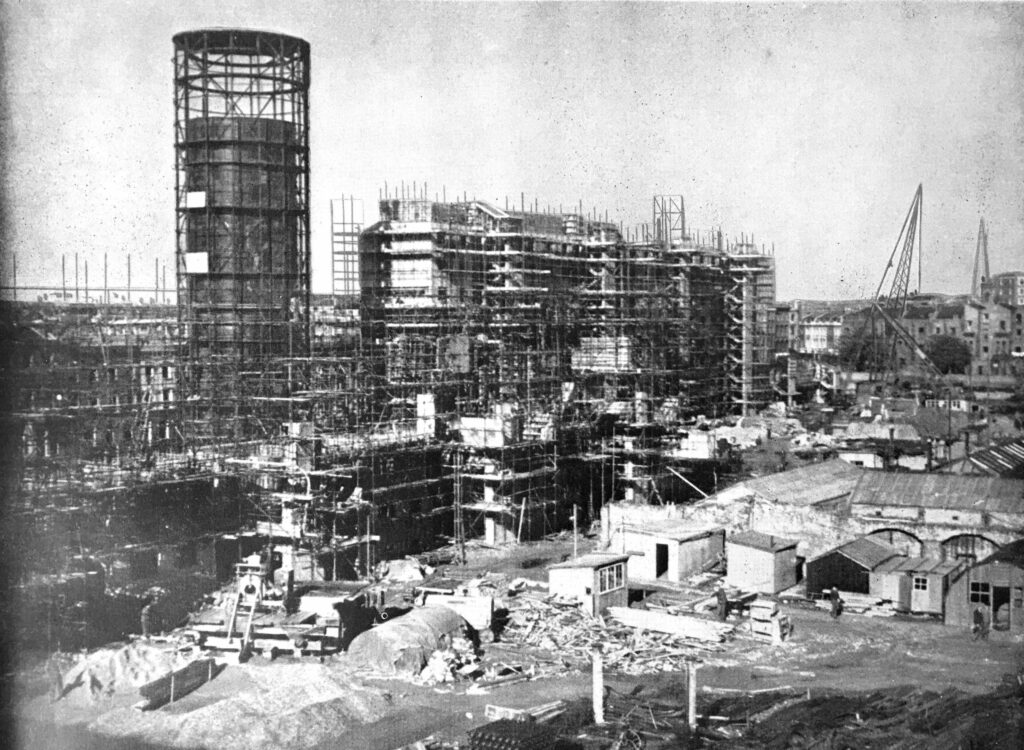

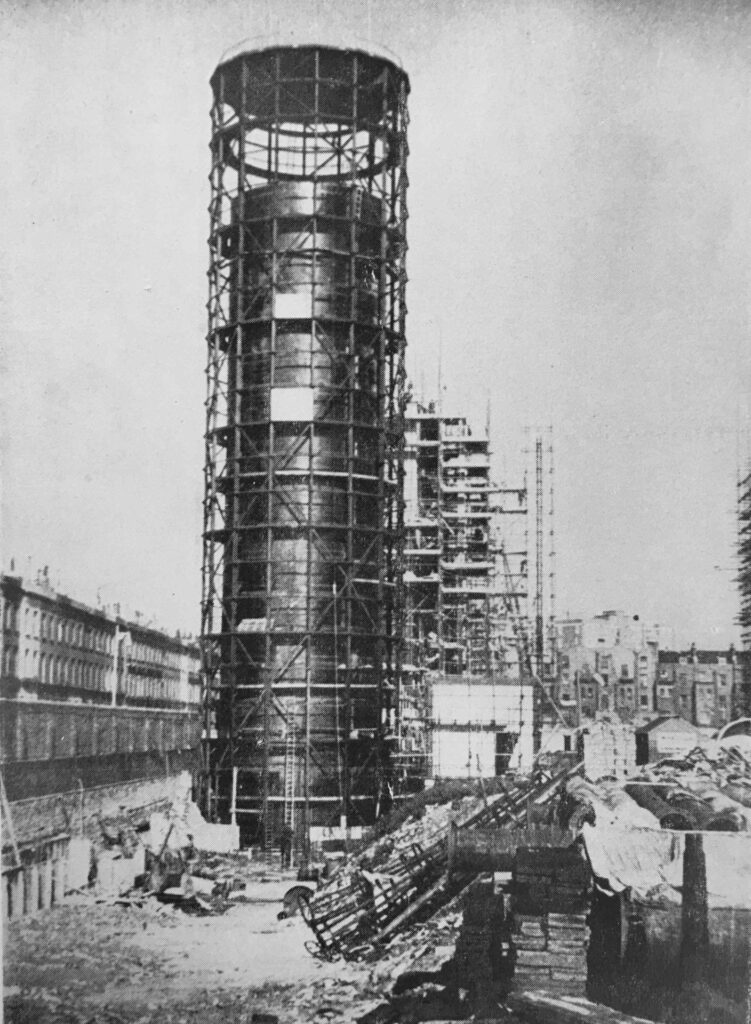

The hot water accumulator tower, along with the rest of the heating system was constructed at the same time as the rest of the Churchill Gardens estate:

The system had a number of safeguards built in as the Ministry of Health required assurance that the system would prevent the release of water at 200 degrees onto anyone who was working on the system. This included measures such as automatic stop valves which would operate when a fall in pressure was detected.

The outer surface of the tower consists of a steel framework with translucent glass panels.

Within the tower was the accumulator vessel which was 126 feet in height, and 29 feet in diameter. Constructed of mild steel plates and with a 3 inch layer of cork to provide insulation.

The project would save a considerable amount of coal, with the text in the book calculating a total of 10,000 tons of coal saved each year by taking the waste hot water from Battersea Power Station.

The amount of heat supplied to the individual flats across the estate was not measured, and a standard charge was applied to all residents for the service. For other buildings, the charge was based on the surface area of the installed radiators.

The hot water accumulator tower, and the first blocks of flats on the estate on the day of the official opening in 1951:

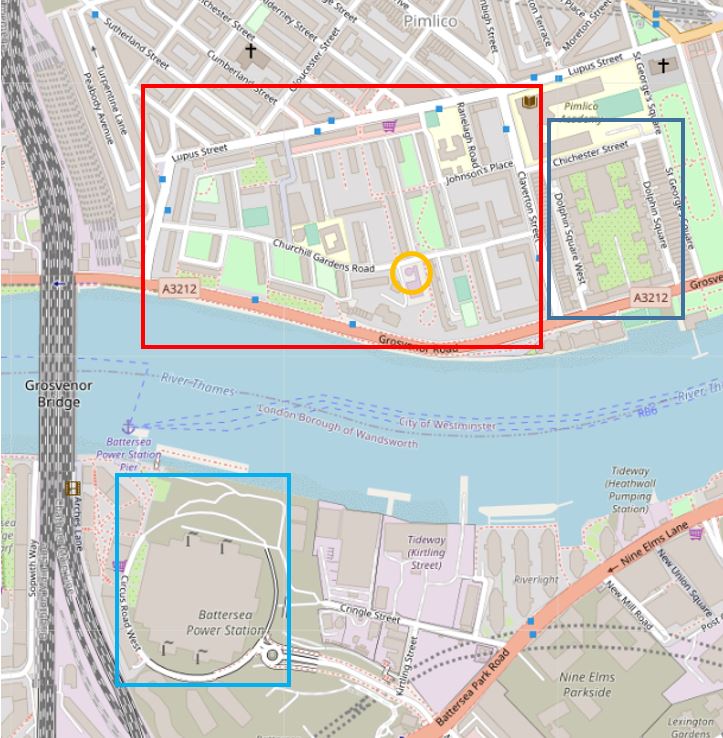

The following map shows the area today, with the Churchill Gardens estate within the red box, Dolphin Square with the blue box, and the hot water accumulator tower marked by the orange circle. Battersea Power Station is across the river marked by the light blue box (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

I went for a walk through the Churchill Gardens estate to find the accumulator tower and to take a look at the estate. Starting at the eastern side of the estate, I walked through the road that runs through the centre of the estate – Churchill Garden Road.

This is the view looking into the estate from Claverton Street:

Map of the estate at the entrance from Claverton Street:

Along with an early speed limit sign:

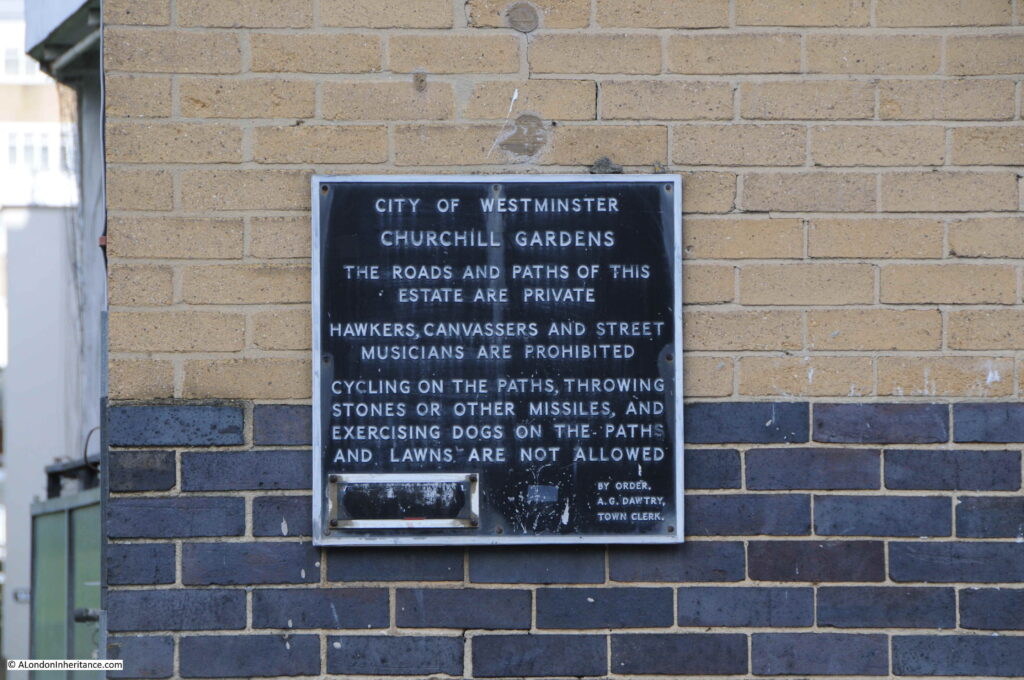

The A.G. Dawtry. Town Clerk mentioned on the speed limit sign was Sir Alan Dawtry, who was town clerk, then chief executive of Westminster City Council from 1956 to 1977. He lived for 61 years in the nearby Dolphin Square complex and was instrumental in saving the building when in the 1960s the company that owned Dolphin Square was going through financial problems, and there was a risk that the buildings would be sold off and converted to a hotel.

The above sign probably dates from the later part of the 1950s, as the estate was being completed.

Pre-war, the area occupied by the Churchill Gardens estate had consisted of industrial buildings and terrace houses. Bomb damage during the war, and the slum conditions of the housing meant that the area was ideal for redevelopment.

The 1943 County of London plan had proposed the development of large, well planned estates, and at the end of the war, Westminster City Council launched a competition for the design of a new estate.

The competition was won by Philip Powell and Hidalgo Moya, who were also responsible for the design of the Skylon for the Festival of Britain, the Queen Elizabeth Conference Centre in Westminster and the Museum of London building at London Wall.

The winning design by Powell and Moya included buildings with a variety of heights, consisting of eleven storey blocks to three and four storey houses and maisonettes. This was intended to break up any monotony across the estate, and to attract a broad cross section of residents.

Gardens and playgrounds would be provided between the buildings, and to address the urgent need for post war housing, the estate was designed to accommodate a high density of 200 people per acre, which was the maximum allowed at the time.

The first part of the estate that we reach from Claverton Street was the last finished. Built in the early 1960s, this part of the estate makes more use of glass than the rest of the estate:

One of these 1960 to 1962 blocks crosses Churchill Garden Road, almost creating the impression of a gateway to the rest of the estate:

Looking along Churchill Garden Road, we can see the main blocks of flats:

The road curves as it runs through the estate, so the main blocks of flats do not form a continuous wall along the road. They are also aligned north – south so as to maximise the amount of day light that would fall on their main east – west facing windows.

The blocks that were built during the first phase of construction, from 1946 up to 1951 have large, glazed stairways protruding from the sides of the blocks. Later blocks would have galleries running along the length of the blocks.

Well kept gardens between the blocks:

Shelley House with a glimpse of the hot water accumulator tower to the right:

In the above photo, a blue plaque can be seen on the wall.

Shelley House was one of the first four blocks completed by 1950 and the blue plaque is a Festival of Britain Award for Merit granted to these first blocks. These four blocks (Chaucer House, Coleridge House, Shelley House and Keats House) along with Gilbert House and Sullivan House on the western edge of estate, and the accumulator tower are also Grade II listed, and indeed the whole estate has been designated as a conservation area.

The Festival of Britain Award for Merit:

Looking back along Churchill Garden Road, and the block on the left has another plaque:

This plaque marks the official opening of the estate on the 24th July 1951 when the first phase of the estate, including the hot water accumulator tower, had been completed:

In the 1951 book by the Association of Consulting Engineers, the estate was called the “Pimlico Housing Estate”, as the estate had not yet been given an official name. A newspaper article in the Westminster and Pimlico News dated the 23rd March 1951 provides the sources of the name:

“It was disclosed at Westminster Council meeting that the name ‘Churchill Gardens’ was the brainwave of Housing Committee chairman, Councilor Miss Paton Walsh.

Mrs. Winston Churchill has agreed to perform the opening ceremony of the estate and of the district heating undertaking on Thursday, July 19.

Miss Paton Walsh pointed out that Mr. Churchill had many connections with Westminster in that he had lived and worked there and he was also their first honorary freeman of the city.”

The official opening covered the first phase of the estate and construction would continue into the 1960s. The 1950s were a difficult time for construction as there were so many competing demands for workers and materials as post war reconstruction gathered pace. This was also having an impact on Churchill Gardens as this article from the 3rd of August, 1951 edition of the Westminster and Pimlico News reported:

“Heartbreaking – It will be heartbreaking for home-seekers if flats at Churchill Gardens are held up while huge Government buildings started in the city are favoured and supplied with all the steel they need.

Sir Harold Webbe, Westminster’s MP attended the opening of Churchill Gardens. He is fully acquainted with the position. If there is a grave delay in the building of these flats he will undoubtedly use his influence in an effort to get things moving.”

Although the streets and houses that Churchill Gardens replaced had suffered bomb damage, with many regarded as slums, they were still occupied, and people were only moved when building had reached their part of the future estate. In 1959, contractors were preparing for demolition of the houses on the eastern edge of the estate ready for construction of the blocks that would be built in the early 1960s, however as the Westminster and Pimlico News reported on the 31st July 1959, there could still be delays:

“Demolition of houses in Claverton Street and Ranelagh Road, Pimlico on the site of Section IV of Churchill Gardens housing estate depends on rehousing the families still there.

Ald. C.P. Russell, chairman of the housing committee, said this at the Westminster Council meeting in a reply to a question put by Cllr. O.M. Boyd.

If rehousing proceeded at the anticipated rate, he expected demolition to start in the sprint of 1960.”

Another plaque from A.G. Dawtry. Town Clerk, this time banning Hawkers, Canvassers and Street Musicians, along with cycling on paths, throwing stones or other missiles, and that exercising dogs on the paths and lawns is not allowed.

It is at this point in the estate that we meet the hot water accumulator tower:

At the base of the accumulator tower are buildings that house equipment for the heating system.

The supply of hot water from Battersea Power Station ended in 1983, when the final generators at the power station closed.

The system supplying heat to Churchill Gardens was then converted to what we would now call as District Heat and Power system. In the buildings at the base of the accumulator tower are boilers along with heat and electricity generating systems which produce heat for distribution across the estate, along with electricity which is fed into the National Grid, which provides revenue to help subsidise the costs of the system.

A poor view through the fence into the equipment rooms at the base of the tower, along with a graphic of the tower on the glass:

The range of the system has extended from the original 1951 installation. As well as Churchill Gardens, the system now provides heating for Abbots Manor, Russell House and Lillington Gardens, with 5km of underground pipes serving 3,250 homes along with schools and commercial premises.

Another view of the equipment rooms, with the brick base of the hot water accumulator tower in the right:

When you get up close, you can see that the tower is built within a deep pit, the following photo shows part of the side walls to this pit:

These walls look as if they have some age, older than the Churchill Gardens estate, and their original purpose is rather surprising.

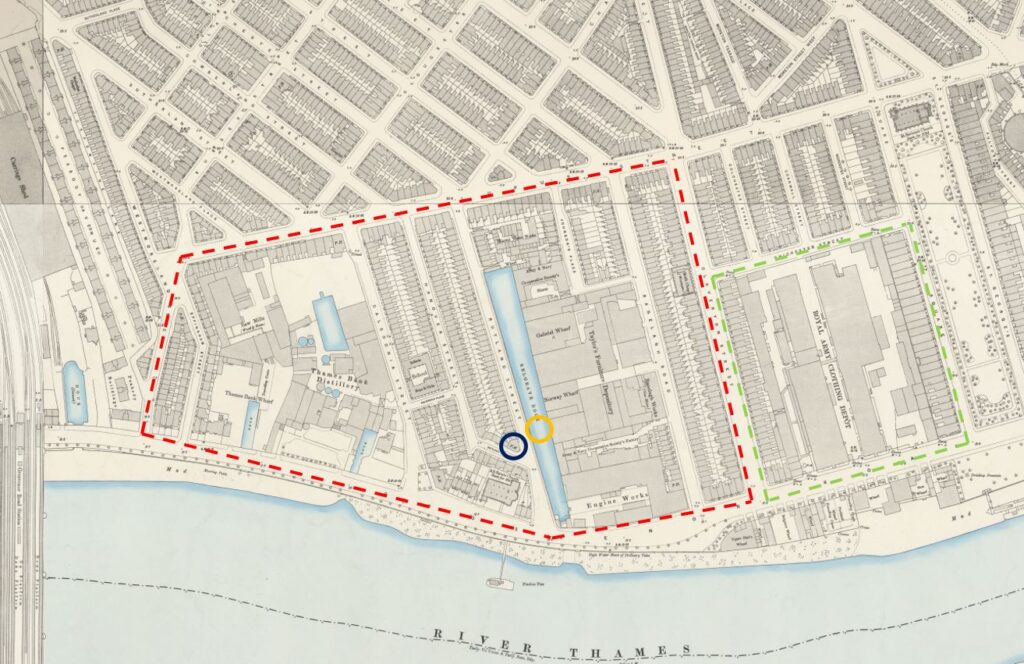

Before the war, there was a considerable amount of industry in the area now occupied by the Churchill Gardens estate. A distillery, saw mills, engine works and a furniture stores. There were also a number of wharves and docks, including one long dock called Belgrave Dock. This can be seen in the following extract from the 1894 Ordnance Survey Map (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’:

In the map, I have outlined the area occupied by Churchill Gardens in red and Dolphin Square in green. Note the difference in street layout between the area to the south of Lupus Street and the area to the north, which still remains much the same.

In the centre of the map is a long stretch of water – this is Belgrave Dock. I have marked the location of the hot water accumulator tower with the orange circle, and you can see that it stands in the middle of the dock.

The brick walls that can be seen in the pit next to the tower are the original surviving walls of Belgrave Dock. Rather amazing that these reminders of the areas industrial past survive.

Belgrave Dock seems to date from the early 19th century. The first written reference I can find is from the 26th February 1832 when the London News reported on a number of accidents during some of the very thick fogs that were covering parts of London at the time. As well as the Belgrave Dock, the report mentions the Grosvenor Canal, which was just to the left of the railway tracks on the left of the above map:

“FATAL ACCIDENTS DURING THE LATE FOG – Between eight and nine o’clock on Friday evening, a police constable discovered a woman in the Grosvenor-canal, Pimlico, quite dead: with assistance he got the body out, and conveyed it to the station-house, in Elizabeth street. The body was owned yesterday, and proved to be Mrs. Ann Hart, aged 72 years, residing in St George’s-row, near the wooden-bridge, Pimlico. There is no doubt that the poor old woman had, during the intense fog, walked into the Canal, which is very dangerous from its unguarded state, as she had her clogs on and a basket in her hand when found. She had merely gone out on an errand.

On Friday morning, john Dillon, a police-constable of the B. division, discovered the bodies of two men at the entrance of Belgrave Dock. They proved to be the bodies of Mr. Wilson, of No. 22, Prince-street, Lambeth, a wadding manufacturer, and his son-in-law, Mr. York; who it is supposed walked into the water during the fog.

The place is in a most dangerous state, particularly in foggy weather; and the only wonder is, that more accidents have not occurred. The place belongs to the Marquis of Westminster; and it is to be hoped that his Lordship will give immediate orders to have the evil remedied. We have heard that another female was brought out of the Canal yesterday morning.”

The report provides an impression of what the area was like in the early 19th century, and I like the address for poor Ann Hart as “near the wooden-bridge, Pimlico”.

Walking down the side road to the tower, and this is the view of the tower from the south:

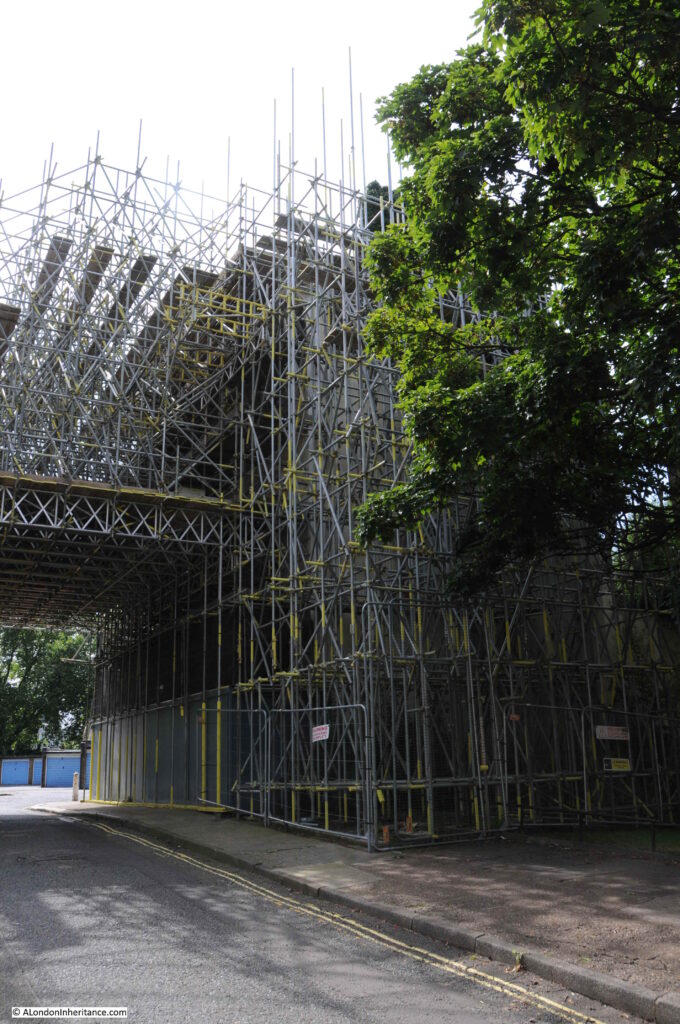

In the above photo, and in the photo below there is a large building completely covered in scaffolding, including scaffolding stretching across the road, presumably to provide some buttressing support to the building.

Buried underneath the scaffolding is a closed pub – the Balmoral Castle. A painted sign can just be seen on the side of the pub.

The Balmoral Castle dates from the mid 19th century and was part of the original development of the area. It can be seen in the 1894 Ordnance Survey extract above under the dark blue circle.

The pub seems to have been the focus for a number of sporting clubs, with the Metropolitan Cabdrivers Rowing Regatta and Mechanics’ United Rowing Club, along with the Pimlico Athletic Club all using the Balmoral Castle as their meeting place.

It was retained during the development of Churchill Gardens as the intention was to include community facilities for the residents. The pub closed in 2004, and the scaffolding was erected in 2014.

There have been plans to redevelop the area occupied by the pub and nearby Darwin House, but these do seem to be progressing rather slowly. In the meantime, part of the pub also seems to be supported by an incredible growth of what looks from a distance like a form of ivy.

Continuing along Churchill Garden Road, and we can see blocks built during later phases. These do not have the multiple external stairs, but have galleries along each floor.

There are design features such as concrete canopies over the entrances to the blocks:

As well as the Balmoral Castle pub, a school was retained during the construction of the estate. This is St. Gabriel’s Church of England Primary School.

The block of flats behind the school has the distinctive white rendered, rooftop drums for water tanks and lift equipment found on the top of the blocks across the estate.

At the end of Churchill Garden Road, I reached the western end of Lupus Street which forms the western boundary of the estate. The following photo is looking back through the estate:

We then walked along Grosvenor Road, along the Thames for another view of the hot water accumulator tower, with the scaffolding surrounding the Balmoral Castle to the left:

Part of the Churchill Gardens estate faces directly onto Grosvenor Road, however there are some original buildings that have survived:

One of which was another pub that has recently closed and is now being redeveloped. This was the King William IV, originally from the mid 19th century and rebuilt in 1880:

The future of the old pub seems to be some form of housing. The Health and Safety Executive Notification of Construction Project taped to one of the windows states that the address is now “Travel Joy Hostels Ltd” and the project will consist of 6 new apartments being designed and built, an extra floor added, and a basement to be constructed to the rear.

The old doors to the pub, with a gutted interior behind:

A short distance along Grosvenor Road is Dolphin Square. This large estate was also provided with heating from the original Battersea Power Station / Churchill Gardens system:

My original reason for exploring Churchill Gardens was to find the hot water accumulator tower, and there was one final part of the original system that I had to visit, and this was Battersea Power Station, which supplied the waste hot water across the river to heat the estate.

Battersea Power Station seen from across the river:

I also wanted to see how development of the old power station and the surrounding area was progressing. In the above photo, the large, glass apartment block that now sits between the power station and railway bridge can be seen on the right.

In the following photo, the additional building on top, and to the side of the power station can be seen:

Crossing the river on Chelsea Bridge, and the apparently random jumble of towers that are spreading along the side of the Thames in Vauxhall can be seen:

Battersea Power Station closed in 1983, and for many years the building was empty, roofless and derelict. After many false starts, much of the old building has been redeveloped. This included the complete reconstruction of the chimneys as the originals were structurally unsafe.

One of the chimneys is planned to included the Battersea Power Station Chimney Lift, which will lift visitors to the top of the tower to get a view from above. It is planned to open in 2022.

The redevelopment of the area follows the standard plan for any London developments – glass and steel apartments above, restaurants, cafes, shops and entertainment venues at ground level.

Alongside one of the new apartment blocks, restaurants, bars and a cinema have been built into the arches that line the railway viaduct:

From the Battersea side of the river, we can look across the river to the blocks of Churchill Gardens, and the hot water accumulator tower that was once supplied by the power station:

The new apartment block on the right closes in on the power station. There are restaurants on the ground floor and a small area of landscaping up to the river:

Looking between the power station and apartment building. A similar glass and steel building has yet to be built on the opposite side of the power station as the area links up with the tower blocks currently being built along Vauxhall.

The area behind and to the east of the power station is still blocked off for construction work, so there is not that much to see, apart from the area in front and around the new apartment building.

On a sunny Sunday, the cafes and restaurants seemed to be doing reasonably well.

The district heating system for the Churchill Gardens estate was the first of its type in London, and probably in the country. There have been a number of systems built since, the latest is the Bunhill 2 Energy Centre, built at the location of the long closed City Road underground station. Rather than waste heat from a power station, Bunhill 2 is unusual in that it takes heat from the Northern line tunnels below.

Bunhill 2 is an addition to the existing Bunhill energy centre built in 2012, which makes use of the more traditional gas powered engine to produce heat and generate electricity. The energy centre is open during this years Open House London event.

That was a rather long post, so thank you if you made it this far.

As usual there is so much to explore and discover. I find the combination of the hot water accumulator tower, built into the old Belgrave Dock, with the original side walls fascinating – relics of two very different industrial activities in Pimlico.

Churchill Gardens does have its problems, but is an estate that shows what can be done to provide housing with innovative design, well chosen materials, and importantly continuous maintenance of the buildings and landscape.

It was a fascinating walk.