Too often, I walk by the numerous memorials in London with little more than a cursory glance to see if there is anything of specific interest. This is even more true for those that I have walked by so many times, they become a part of the street scene. One such memorial is the Bellot Memorial on the riverside footpath at Greenwich – a slim obelisk on a grass mound between two footpaths.

The base of the obelisk facing the river, has the work Bellot inscribed in large letters.

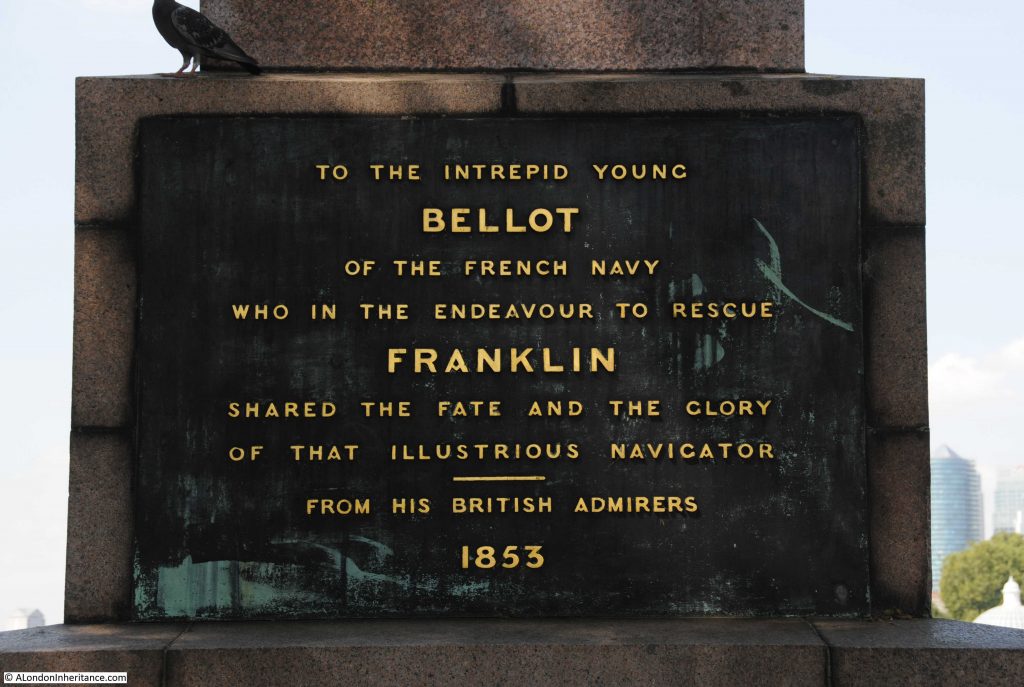

Whilst on the side facing inland there is some text which gives a partial clue as to who the memorial is commemorating.

The key to finding out who Bellot was, and why he has a memorial on the river path at Greenwich is through the second name.

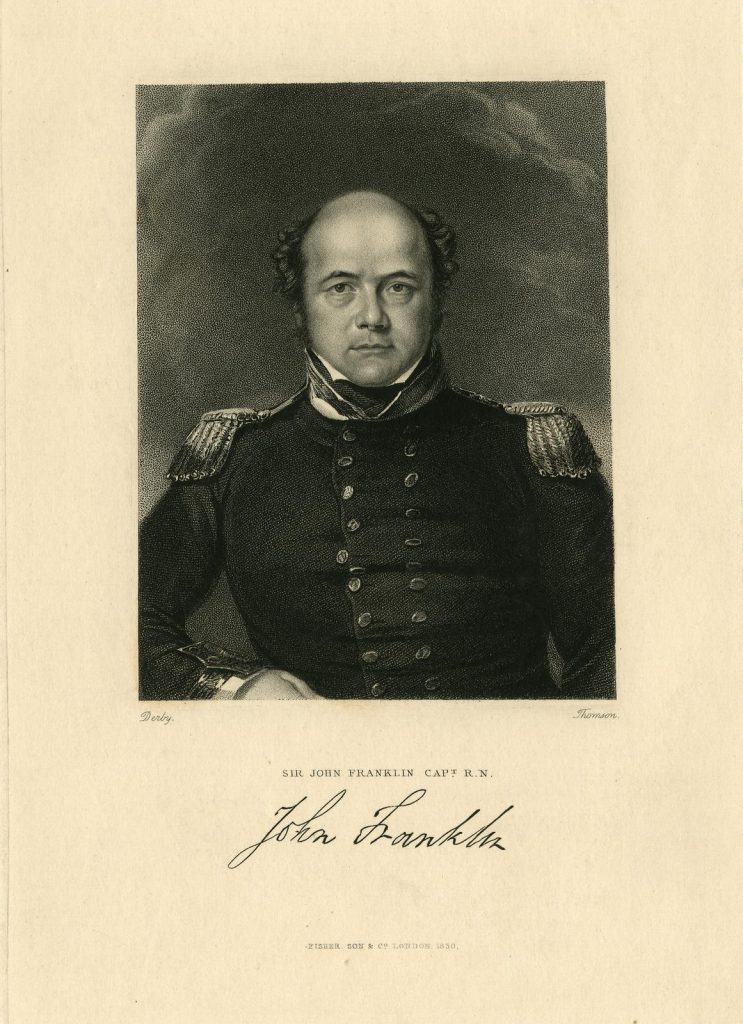

This is Sir John Franklin, the Arctic explorer and Royal Navy officer.

Franklin was a 19th century experienced Arctic explorer, having been part of three expeditions to explore northern Canada and the Arctic. His fourth and final expedition took place in 1845, where he led two ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror on an expedition to explore the final miles of the north west passage, the route from the Atlantic to the Pacific along the north coast of Canada. Finding such a route would reduce the time to travel between the two oceans significantly and would be a major advantage for the Royal Navy and British trade.

The 1845 expedition was the best equipped to date, and included a supply ship which took additional supplies to be transferred to Erebus and Terror at Greenland, leaving the two ships to head to northern Canada fully supplied.

They left the Thames in May 1845, and after transferring supplies, headed west. The last confirmed sighting of the two ships was on the 26th July 1845. They were not seen again.

They were heading to a place where ships did not travel, forms of communication such as radio were still many decades in the future, so it was expected that there would be no contact with the ships for some time, but after two years there was widespread concern as to the state of the expedition and the fate of the crew of the two ships.

Franklin’s wife, Lady Jane Franklin petitioned the Admiralty to arrange an expedition to search for her husband and the crew of the two ships. The Admiralty put up a sum of money for finding the ships, and a number of expeditions set out to northern Canada. One of these was carrying a young lieutenant of the French Navy, Joseph Rene Bellot © The Trustees of the British Museum:

The Illustrated Times of the 1st December 1855 provided some background on Bellot:

“Bellot was a native of Paris, and first saw light in March 1826, his father being by trade a farrier and blacksmith. When Bellot reached the age of five, his father removed from the French capital to Rochefort, and the embryo here was educated in that marine town. In his sixteenth year, Bellot was placed at the naval school of Rochefort, and soon afterwards entered upon his professional career.

From a boy, Bellot was remarkable for his sense of duty, sweetness of temper, and nobility of soul; and, as time passed on, these high and generous qualities not only endured him to his friends, but gave him a strong hold on the hearts of all with him he shared peril and fatigue.

The conduct and career of Lieutenant Bellot in connection with our Arctic expeditions in search of Sir John Franklin, are well known. His own diary, recently published, and read by many with breathless interest, furnishes, of course, the best narrative of adventures and enterprises, and the story becomes more and more enchanting as it proceeds. ‘So often’ says a contemporary, ‘as the Golden Book of Modern Travel comes to be made up, one of its best and brightest pages must be reserved for Joseph Rene Bellot; since rarely, in any age, has love of adventure been ennobled by higher motives and mere unselfish feelings than those which stirred the young French adventurer. The nationality of Bellot, too – his gaiety as well as his goodness – makes his journey peculiarly engaging’.

To indomitable courage and indefatigable perseverance, were added the charms of lightness of heart and poetry of fancy. He seems to have been able ‘to laugh and make laugh’, to dance when a young Orcadian Miss was to be found by way of partner, to read Byron, to think of Scott and to hear about Shakespeare, as if he had been merely one of those Parisian carpet travelers, who imagine adventures in foreign lands, while he lounges homewards, cigar in mouth, as if he had not been a real hero in the hour of danger, hopeful and calm when death was upon him.”

Given his apparent thirst for adventure, an expedition to rescue Franklin must have been a brilliant opportunity for Bellot, so much so, that he participated in two expeditions, the last one would cost him his life.

The first expedition under the command of Captain William Kennedy was during the years 1851 and 1852, and the second, this time under the command of Captain Edward Inglefield, set out later in 1852.

It was during Inglefield’s expedition that Bellot lost his life when “this noble minded officer perished in the Wellington Channel in a gale of wind, by the disruption of ice, whilst carrying dispatches from Beechy Island to Sir Edward Belcher, a service for which he generously volunteered”.

Sir John Franklin, HMS Erebus and Terror, and the crew of the two ships were never found. Lady Franklin continued supporting searches, including later searches for written records that the expedition may have left, however she died in 1875 with no firm conclusion as to her husband’s fate, apart from the fact that he had died.

Sir John Franklin © The Trustees of the British Museum:

After Bellot’s death, there was considerable interest in creating some form of memorial for a French Lieutenant who had died in the search for one of Britain’s Naval heroes and Arctic explorers.

Sir Roderick Murchision, President of the Royal Geographical Society was the Chair of a committee set up to arrange a suitable memorial. Public meetings were held, money was donated and plans were put in place.

The initial plan was for a memorial to be built in Bellot’s home city of Rochefort, however after correspondence with the Mayor of Rochefort it was understood that the city was already planning a memorial, and two separate memorials was not considered the best approach.

The committee therefore decided on Greenwich as a suitable location, as: “Under these circumstances, and being assured that the French government will cordially approve their decision, the committee have come to the conclusion, that Englishmen, wishing to honour in the most emphatic manner the memory of one who was so esteemed and beloved among them as Lieutenant Bellot, should pay to him the same respect as to their own illustrious dead. In this case, if it be decided that a cenotaph, column, or monument be placed on the banks of the Thames, at or near the Royal Hospital at Greenwich, the committee feel assured that every Frenchman who may pass by on the river, or visit our great naval hospital, would see that we had paid to our lamented friend the very highest compliment in our power, and that our tribute was a pledge to be forever before us, and that we desired to perpetuate the mutual good-will which so happily exists between the two nations”.

Over £2,000 was subscribed towards the memorial. the cost was only £500, with the remaining funds being distributed to the sisters of Bellot. The French Emperor, Napoleon III also granted an annuity of 2,000 francs to Bellot’s family.

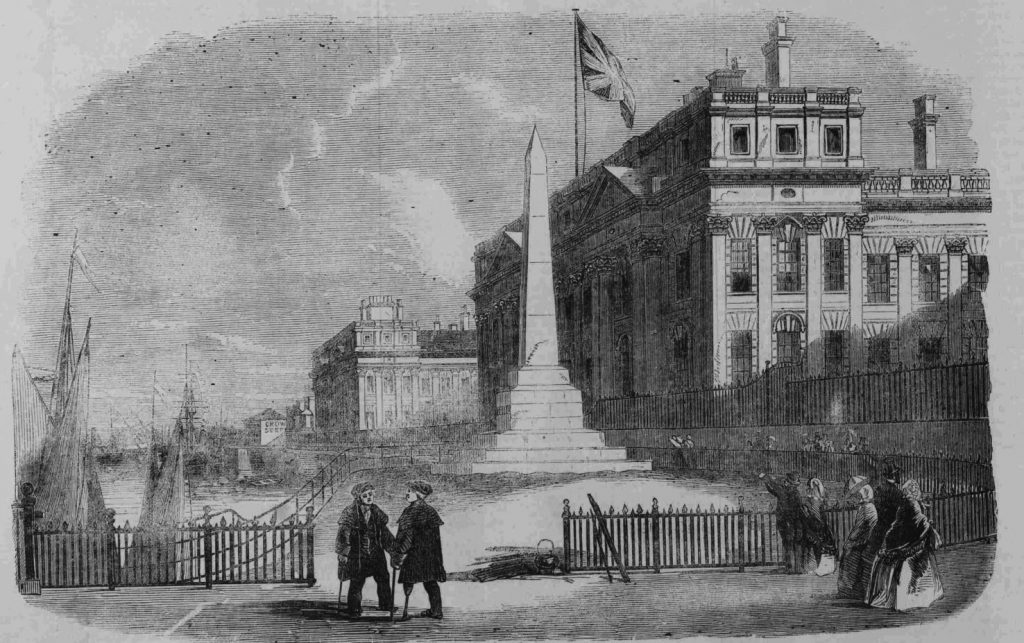

The following print from soon after the memorial was installed in 1856 shows the obelisk of Aberdeen granite, standing on a grass mound between two walkways along the Thames and in front of the Royal Hospital – as it does today.

Bellot is not just commemorated in Greenwich and Rochefort, there is also a geographic feature named after Bellot. On a previous Arctic expedition he had covered, with William Kennedy, over 1,100 miles on foot and dogsled over the ice. They found a previously unknown feature, a channel of water between Somerset Island to the north and the Boothia Peninsula to the south. This channel of water was named Bellot Strait.

A high level map is below, to show the very remote location of the Bellot Strait (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

In a very different location to the Bellot Strait, the Bellot memorial looking over the Thames, a stretch of water with which Bellot and Franklin must have been very familiar.

Although scattered remains would be found of the ship and crew, HMS Erebus was only recently discovered in September 2014. The book Erebus, The Story Of A Ship by Michael Palin provides a detailed account of Franklin’s expedition and the discovery of the Erebus.

But the final word must go to Lieutenant Bellot, who wrote a last letter to friends, to be delivered in the event of his death:

“My dear and excellent Friends – If you receive this letter I shall have ceased to exist, but should have quitted life in the performance of a mission of peril and honour. You will see in my journal, which you will find among my effects, that our captain and four men were necessarily left behind in the ice to save the rest; so, after effecting that, we were compelled to go to the assistance of these worthy fellows. Possibly I had no right to run such a risk, knowing how necessary I am to you in every way; but death may probably draw upon the different members of my family, the consideration of men, and the blessings of Heaven – farewell ! to meet again above, if not below, Have faith and courage. God bless you, J. Bellot”

Interesting account of the legal consequences of Franklin’s disappearance here:

https://medium.com/@abarbararich/out-of-the-frozen-deep-i-e0e2a0e2efd1

Excellent I love anything on the North West passage including this monument to a time in history of great endeavour

Thank you for linking to my writing on the litigation over the will of Edward Couch, an officer of HMS Erebus, and thank you to the author for the interesting post on Bellot’s memorial

This is an interesting article to me. I am from Wainfleet in Lincolnshire, which is only 10 miles from Spilsby where Sir John Franklin is from. There is a statue of him in Spilsby. I enjoy your articles.

Thank you.

Lovely article on a memorial which for many years left us perplexed. It was missing the black inscription and we used to scratch our heads about who earth Bellot was and why such a huge memorial. In the days before the internet, it was often difficult to find information on statues of long forgotten heroes.

You are probably aware that they recently found HMS Terror, in Terror Bay, which apparently is just a coincidence. They have discovered that Captain Crozier’s cabin has a metal locker which might still contain his log books (written on linen not paper). The great mystery of the Franklin Expedition may yet be partially resolved.

There is also a Bellot street in East Greenwich.

Very interesting read-much welcomed on a grey Thursday morning on lockdown

An interesting post as ever. There was a prog recently on pbs on the successful attempt to find the Erebus and there it was almost intact with guns etc. Think prog was made in 2016 . I’ve always been fascinated by the Franklin expedition and here is another footnote to the story. Well spotted.

My regular walk past this memorial has been forever changed by your article, and Bellot’s life remembered well so that it and he are not lost to us any longer.

Thank you for this and for all that you write in your regular newsletter, always so full of careful research, thought and strongly felt humanity.

Brilliant!

John Rae, an Orkney surgeon was the first to find credible information on the fate of Franklin. Rae embraced the indigenous Innuits, learning how to survive in such hostile conditions but was snubbed by Victorian society who dissmissively said that he had “gone native.”

From the Innuits he brought back a silver plate engraved, Sir John Franklin, but also learnt the possibility that there was evidence of canniblasm amongst the crew. When this was leaked to the press. Lady Franklin and many others including Charles Dickens shunned him and he was airbrushed from society.

There is a museum in Stromness with a Rae exibition that I`ve visited.

I am 18 months late in reading this post but thank you Janice for highlighting the important contribution to the story made by the esteemed Dr John Rae. It is only in recent years that the British Admiralty has finally recognised that contribution.

My wife is an avid follower of yours and every week enjoys your posts. She shared this post with me in particular as I used to walk around Greenwich every week whilst my son was at his Maker Club for two hours.

As Janice above has commented, John Rae discovered the fate of the Franklin expedition as well as the first passable Northwest Passage route (later confirmed passable by expedition by no less than Roald Amundsen) but was denounced by and had his reputation ripped to shreds by Lady Franklin.

There is a brilliant book by Ken McGoogan called Fatal Passage about Rae that is a excellent read, covering his life in Canada his adoption of native methods of living, the discovery of the passage and the fate of the Franklin crew.