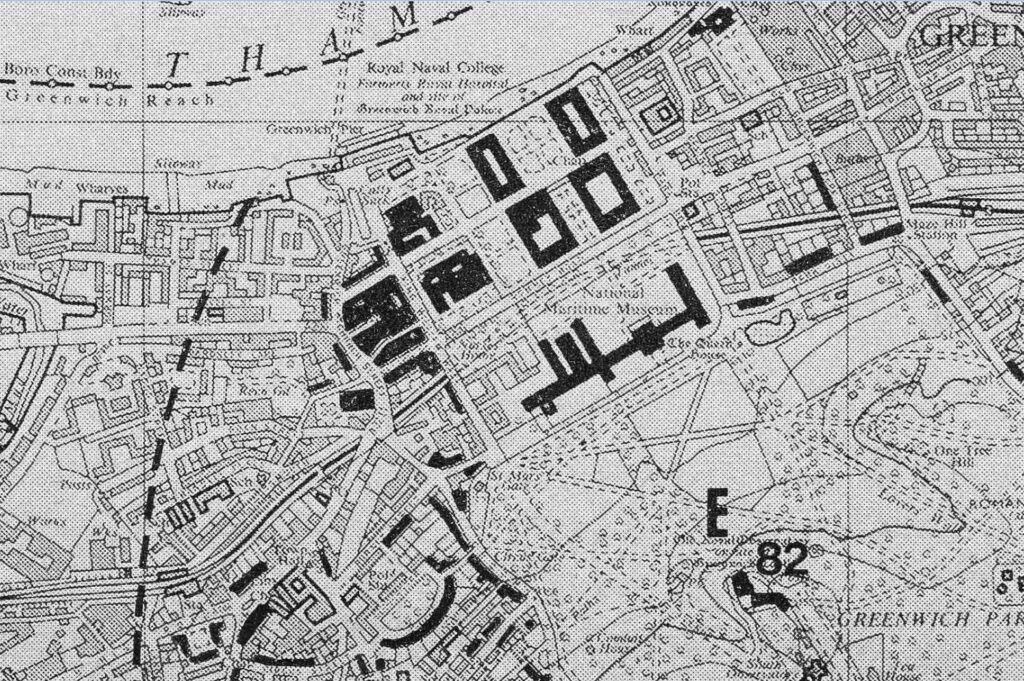

Following last week’s post, this is part two of my exploration of Greenwich, looking for the locations marked as potentially at risk from development in the Architects’ Journal of 1972.

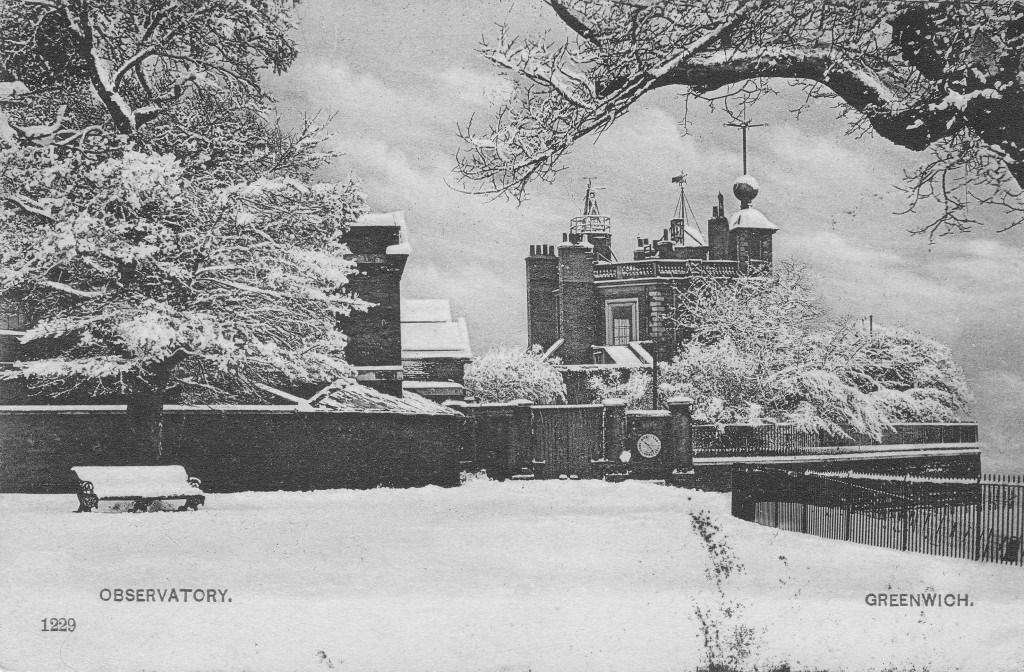

In last week’s post, I started at the Royal Observatory (the black buildings under number 82 in the following map), and then explored the streets and buildings to the lower left of the map.

In today’s post, I am working through the upper part of the map, either side of the old Royal Naval College and National Maritime Museum, starting with the following building in Nevada Street, on the corner with Crooms Hill:

This was the Spread Eagle, an old coaching inn, which still has the name Spread Eagle Yard above the arched entrance to the yard where horses were stabled to the rear of the building.

The current building dates from a 1780 rebuild of the inn, and it was closed comparatively recently in 2013.

The brown plaque on the left of the building is to Dick Moy (1932 to 2004) who was an historian and art dealer who restored and worked from the inn.

Just to the left of the Spread Eagle, Croom Hill changes to Stockwell Street, and we can see a mix of architecture, with buildings from the 18th century through to the 21st century University of Greenwich Galleries on the left:

On the corner of Crooms Hill and Nevada Street, opposite the Spread Eagle is Ye Old Rose and Crown which claims to date from the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, however the brick building we see today dates from 1888:

You can also see from the above photo that the Rose and Crown is surrounded by the Greenwich Theatre, with a new entrance on the right and original buildings on the left.

The original buildings date back to 1855 when it was a Music Hall. A change to a cinema followed in 1924, and the theatre opened in 1969 following a campaign to save the building from demolition in the 1960s.

St. Alfege

Continuing down Stockwell Street, and we find a superb view of the church of St. Alfege:

There has been a church on the site for around 1000 years, however the church that we see today dates from between 1712 and 1718 and was designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor. It was one of the so called fifty new churches planned to be built in the areas around the then outskirts of London, in the places that had been expanding rapidly and did not have the number or size of churches needed to support increasing populations.

The previous church on the site had suffered a roof collapse during a storm, and to save money, the tower of the earlier church was included in the new church, although this was not Hawksmoor’s original plan.

In 1731, the earlier medieval tower was extended and clad in limestone, so presumably, parts of the medieval tower are still within the structure today.

On entering the church, we see the altar at the eastern end, and two galleries running either side of the church:

In the above photo, on either side of the arch leading to the altar, there are two ornate panels, which list benefactors dating back to 1558, when William Lambarde “Founded and Endowed a College, the first Public Charity after the Reformation for 20 poor men and their wives. 8 to be off this parish and dedicated to Queen Elizabeth”:

Other benefactors include in 1577: “William Riplar, Fisherman gave his house called the Peter boat to the poor for ever” and in 1605, Joyce Whitehead gave 5 shillings to repair the church every year. All fascinating local tales of charity.

In front of the altar is a plaque which records why the church is dedicated to St. Alfege, and why it is on this site:

The plaque is hard to read in the photo, but it states that “This church stands on ground hallowed by Alfege Archbishop of Canterbury martyred here 19th April 1012”.

St. Alfege (the spelling of the name includes variations such as Alphege), was born in a village near Bath, and became the Abbot of Bath and then the Bishop of Winchester. In 1005 he was appointed the Archbishop of Canterbury.

In the early decades of the 11th century, the Danes were invading much of southern England and in 1011 they attacked Canterbury, burning the Cathedral and plundering the city.

Alfege was taken hostage, apparently to be held for ransom, and he was transported by ship to Greenwich.

It was here that he was killed. It is impossible to know exactly how this happened, but many stories tell that Alfege told his captors that the ransom was too high, and that it should and would not be paid. In a drunken rage, they pelted him with cattle bones and an axe head, which killed him.

It was this event which resulted in Alfege being made a Saint (although there has been some dispute about this, and whether he died because of his faith, or the size of the ransom), and to the first church being built on the site of his death later in the 11th century.

St. Alfege is not buried in Greenwich. After his death he was buried in St. Paul’s, then soon after, his body was moved to Canterbury Cathedral, where it remains to this day.

Although Alfege is not buried in the church, there are a number of well known names who have been, including one who may also have left musical evidence of his connection with the church.

Thomas Tallis was a 16th century English composer who was organist in St. Alfege from 1540 to 1585, and is believed to have lived in Stockwell Street close to the church during the later years of his life.

In the church is the keyboard from one of the earlier organs. The majority of the keyboard dates from the 18th century, however it is believed that parts may date back to the 16th century and may have been in use when Tallis was the organist:

Another burial in the church is that of General James Wolfe (Wolfe’s statue is the one on the hill next to the Royal Observatory – see last week’s post). Wolfe had a house in Greenwich and also a family vault in the church.

He died in Canada during a battle to take Quebec from the French, and it is for his part in the wars to capture French possessions in north America that Wolfe is best known, although this was the culmination of a long military career.

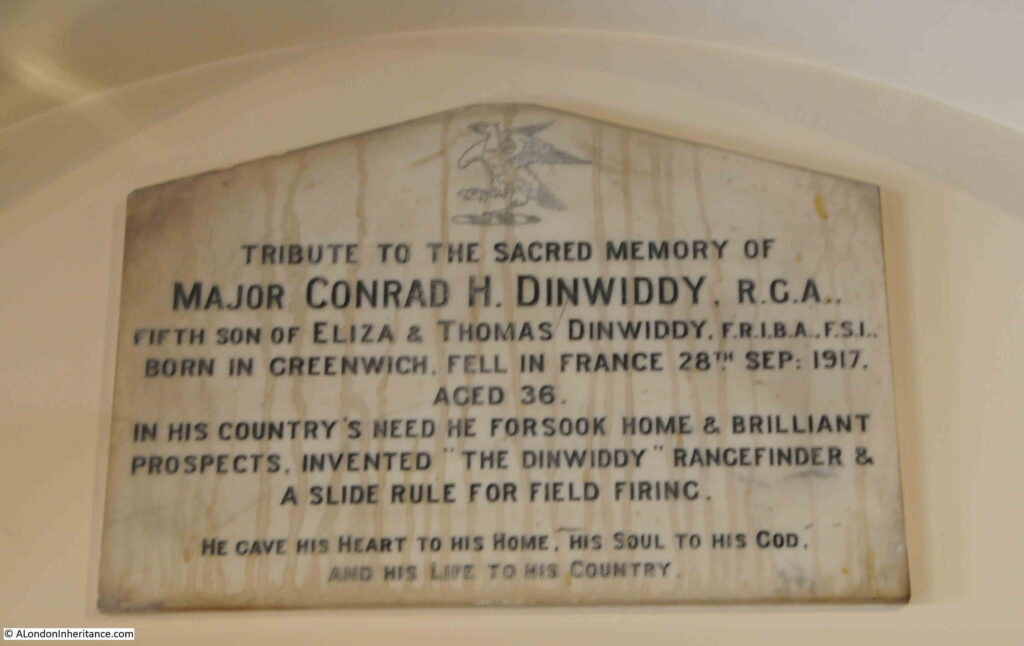

There is an interesting monument in the church that includes a reference to the invention of the “Dinwiddy Rangefinder”:

Conrad Dinwiddy was born in Greenwich in 1881, and was the son of London architect and surveyor, Thomas Dinwiddy who had an architectural practice based in Greenwich.

During the First World War, German Zeppelins were making bombing attacks on London and Conrad Dinwiddy saw one of these attacks on Woolwich by Zeppelin L13. He saw that although there were several searchlights trained on the Zeppelin and many guns attempting to hit the attacker, none were actually hitting, and that it appeared impossible to accurately aim a gun and fire a shell to hit a target at height, which was also moving at speed.

Like his father, Conrad was also a surveyor, so was familiar with use of instruments such as theodolite, however working out the positions of a moving target were far more complex that traditional surveying of fixed objects.

He came up with a plan for two stations, based 500 yards apart. One was a primary observation station and was connected by telephone to the secondary station.

The rangefinder worked by the primary observation station making measurements of position and height which were then adjusted to improve accuracy with the measurements of the second station which was, at 500 yards distant, on a fixed baseline.

The Dinwiddy Rangefinder was put into production, but as the war progressed, the threat from bombing changed from Zeppelin’s to aircraft, and rapid technical advances improved other methods for defending London against aerial threats, however the Dinwiddy Rangefinder remains as an example of the rapid response to a threat from a Londoner who saw the potential impact to their city.

Conrad Dinwiddy joined the Royal Garrison Artillery in 1916, where he was posted to the Western Front in charge of a six inch howitzer battery. He would continue inventing improvements to how guns were aimed, firing from barges, and the methods for transporting ammunition.

He was wounded by German battery fire on the 26th of September, 1917, and died the following day. He is buried in a military cemetery in Belgium. The memorial in St. Alfege has the wrong date, as he died a day earlier on the 27th of September.

A fascinating story from this small plaque in the church.

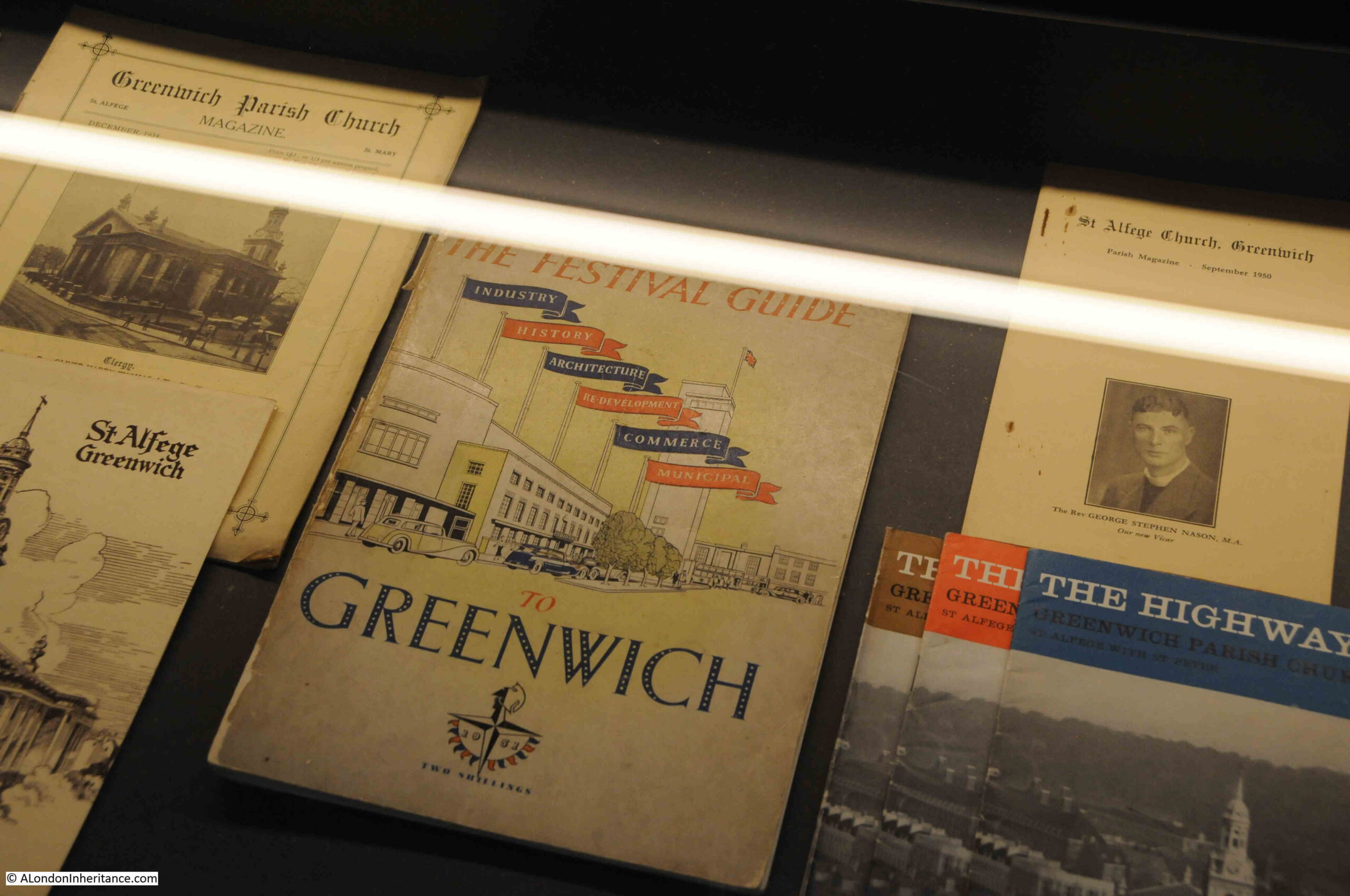

As I left the church, I had a look in a small room on the left as you exit, which has a number of display cabinets on the history of the church and I noticed the following: The Festival Guide – Greenwich

If you have read the blog for a while, you are probably aware of my interest in the Festival of Britain, and this guide is another example of how the festival was intended to reach across the country, and towns and villages, and suburbs of London were also having their own interpretation of the festival, with local events and guides.

Outside the church, on the corner of what is now Greenwich High Road and Nelson Road is a Bill’s restaurant in a rather ornate corner building:

I did wonder if the building was a new build on the site of bomb damage to the terrace you can see to the left, however the style of the building shows that it is pre-war, and it was indeed built in the early 1930s for the Burton menswear chain.

The road then changes to Greenwich Church Street, and here we find one of the entrances to Greenwich Market:

The terrace buildings on either side come to what looks like a designed end where the entrance to the market is located, and this indeed was the plan.

The terraces on either side of the entrance were built as part of an overall redevelopment of the market area around 1829 / 30. They are all Grade II listed, and if we look to the left we can see how the symmetrical design of the terrace curves along the street:

Further along Greenwich Church Street, at the junction with College Approach, the Spanish Galleon pub is on the corner:

The Spanish Galleon pub dates from the same market redevelopment as the terrace houses featured above. As with so much of Greenwich, the pub is Grade II listed. A pub is believed to have been on the site for many years prior to the 1829 / 1830 redevelopment.

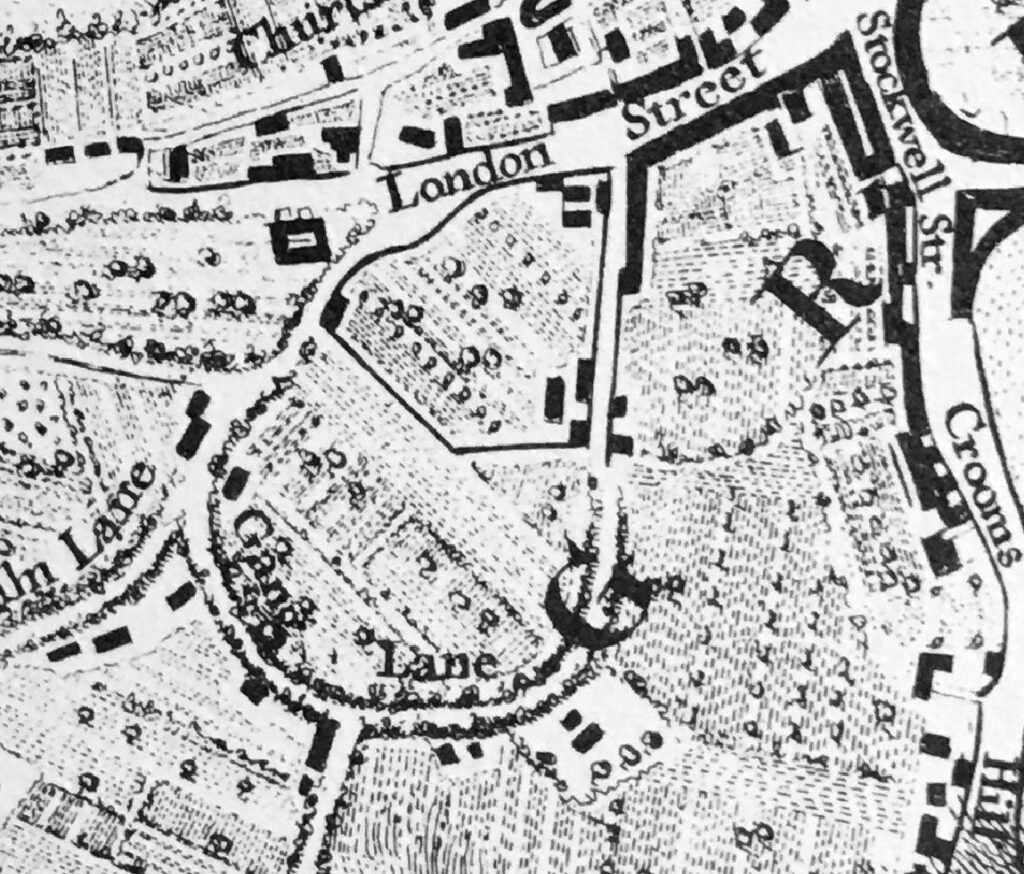

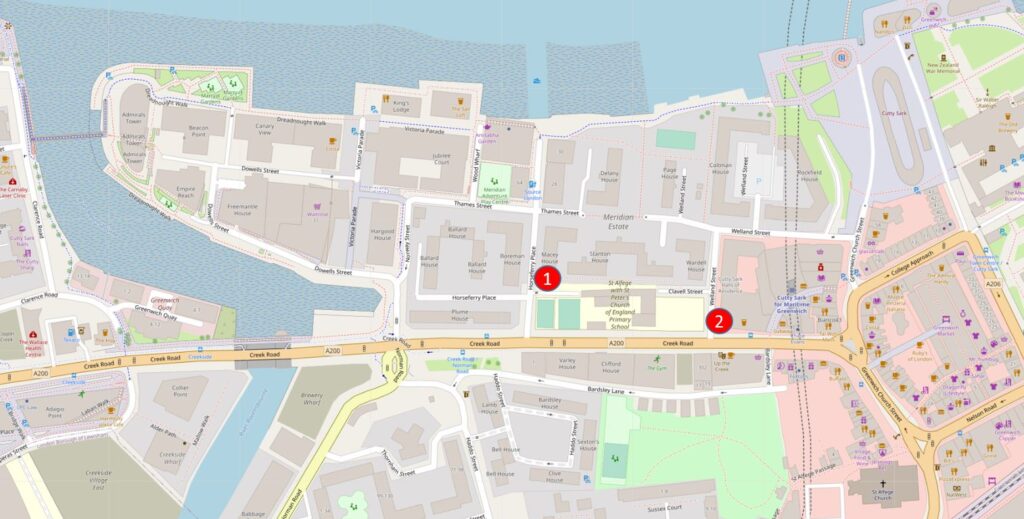

The market can be seen in the following map, located in the centre of some of the streets we have been walking along (on the left of the map) (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

Up until the start of the 19th century, this was an area of narrow lanes and alleys, and with the growing importance of Greenwich, a redevelopment of the area was needed, and the architect Joseph Kay was commissioned, and it is his work we see today.

Joseph Kay (1775 to 1847) worked on a wide range of building projects across the country. In London, he was appointed surveyor to the Foundling Hospital in 1807, he laid out the gardens in Mecklenburgh Square, he was employed by the Marquis Camden on his Camden Town Estate, and in 1823 he was appointed surveyor of Greenwich Hospital.

The view along College Approach, with the Spanish Galleon on the right, and the terrace along the right being on the northern side of the market:

Greenwich has had a market since the 14th century, however the current market dates from a charter granted in 1700. It was originally located on part of the Seamen’s Hospital site, close to the West Gate. It relocated to the current site as part of Joseph Kay’s redevelopment of the area, and was originally a market selling fruit and vegetables, fish caught by Greenwich fishermen, plants and seeds, with sellers of pottery, glass and household goods around the edge of the main market area.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, the popularity of the market as a place for fruit, vegetables etc. declined, and the market transformed into in place where stallholders sell all manner of arts and crafts products, with a cluster of food stalls at the northern end.

The market is open seven days a week, but gets really busy at the weekends.

A view through the market:

The market, and the surrounding buildings of the 1830 redevelopment are part of the buildings marked in black in the Architects’ Journal article, and with the decline of the traditional use of the market, the market could have been so easily lost during the 1970s / 80s, however the market is owned and managed by Greenwich Hospital who fortunately have both a historic and long term view of the importance of the area.

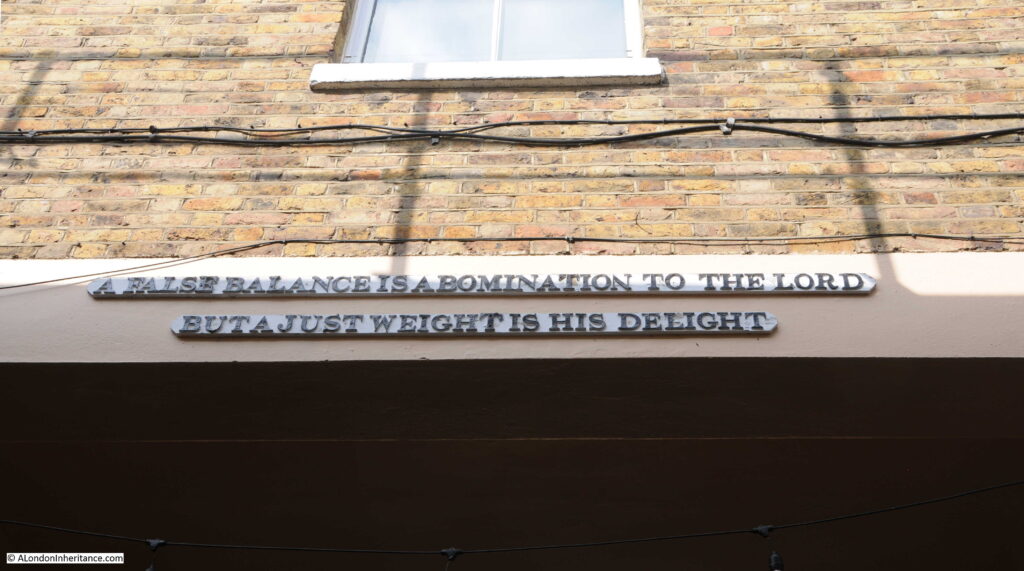

A message to those leaving the market:

Just to the east of the market entrance in College Approach is another Grade II listed pub, the Admiral Hardy:

Greenwich is very well served with pubs. The Admiral Hardy was again part of the 1830 redevelopment, and to the right of the pub in the above photo is a small part of what was the Royal Clarence Music Hall, built over the entrance to the market.

The music hall was named after the Duke of Clarence, later King William IV, and the street outside, College Approach was originally Clarence Street.

At the end of College Approach is the Grade I listed West Gate into the old Royal Naval College. The listing includes the gates, piers, globes and brick lodges on either side:

The globes on top of the piers are fascinating. Each globe is of Portland Stone, of 6 feet diameter and weighs around seven tons.

The globes date from the early 1750s, and were installed to commemorate Commodore George Anson’s around the world voyage, which is a remarkable story, and resulted in the surviving crew becoming rich through the capture of a Spanish treasure ship.

The globes are marked with lines of latitude and longitude in copper strips

It was common practice in the 18th century for the story of voyages such as Anson’s to be published as partworks, and Anson’s voyage was covered in 15 issues starting in August 1744, and was written by “An Officer of the Fleet”.

Adverts for the publication enticed the reader with hints of the dangers faced by the crew and descriptions of a part of the world that the majority of people knew very little about:

“This Work contains a very faithful and exact relation of the many Difficulties and Dangers the Fleet met with in the Voyage. An Account of the Loss of their Ships, and what dreadful Miseries and Hardships the poor sailors met with, being forced on desolate islands, where many of them perished for want. Also an Account of the manner of their Living in the Voyage on Seals, Wild Horses, Dogs and the incredible Hardships they frequently met with for want of Food of any Kind. The Loss of the Wager (one of the ships) and the Behaviour of the Captain (who shot one of his Mates), his Officers and Crew, fully and faithfully related. Their plundering and destroying of the City of Payta, where the Commodore got immense Riches, and his sailing afterwards into the East-Indies, where he was well received by the Vice King of China, who furnished him with Provisions and Necessaries to enable him to pursue his Voyage to England. With a particular Account of his taking the rich Aquapulco Ship.

This Book will give a complete Description of the several places where the Fleet touched, how they plundered and distressed the Spaniards; the Manners, Customs, Religion, Trade and Manufactures of the People who inhabit this large and almost unknown Part of the World.”

All for two pence an issue, with a free print of Commodore Anson with the first issue.

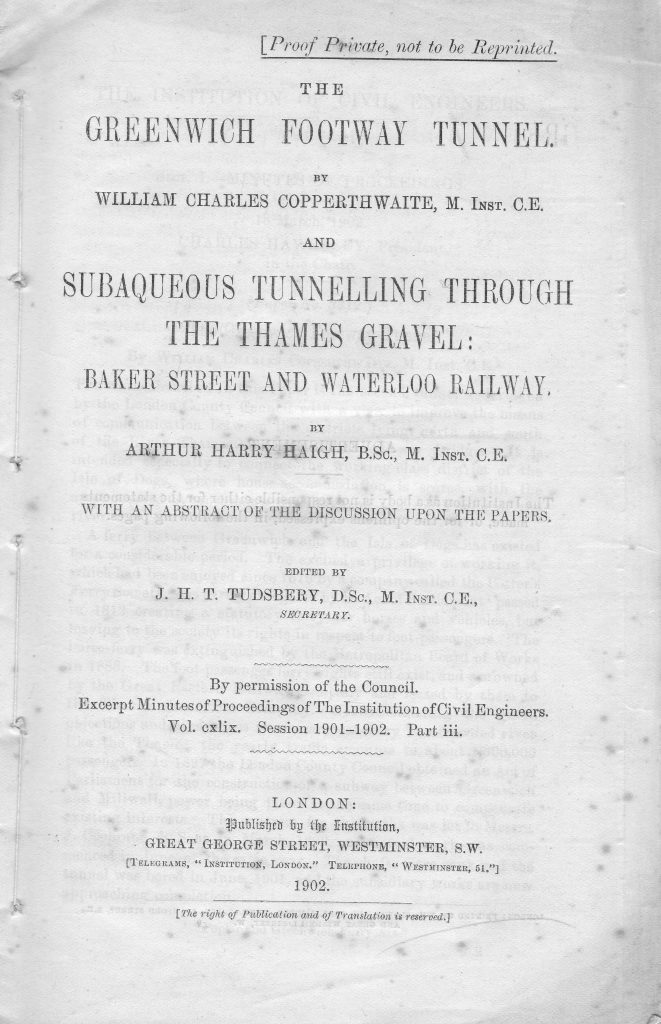

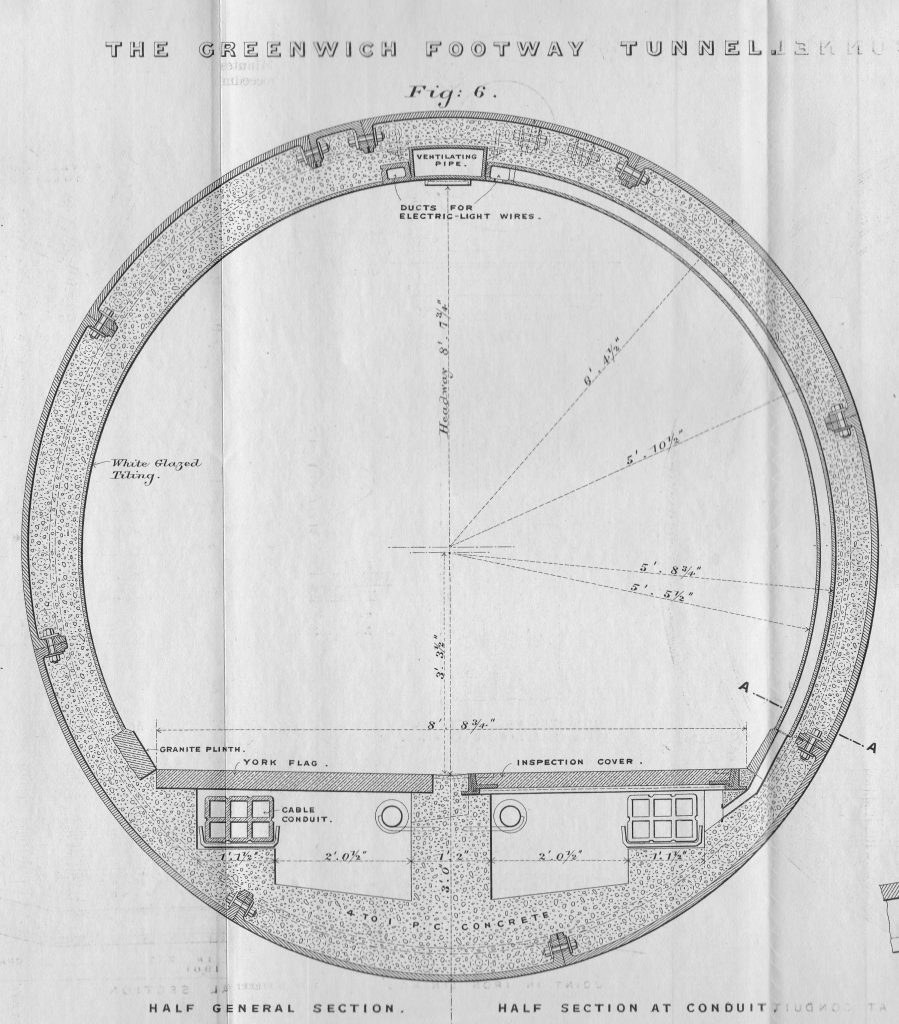

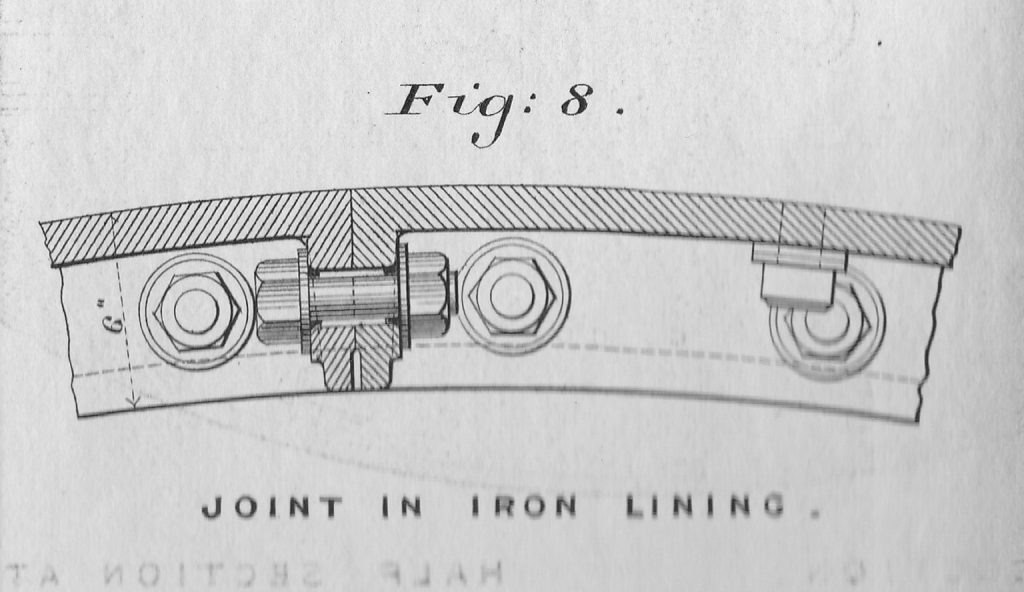

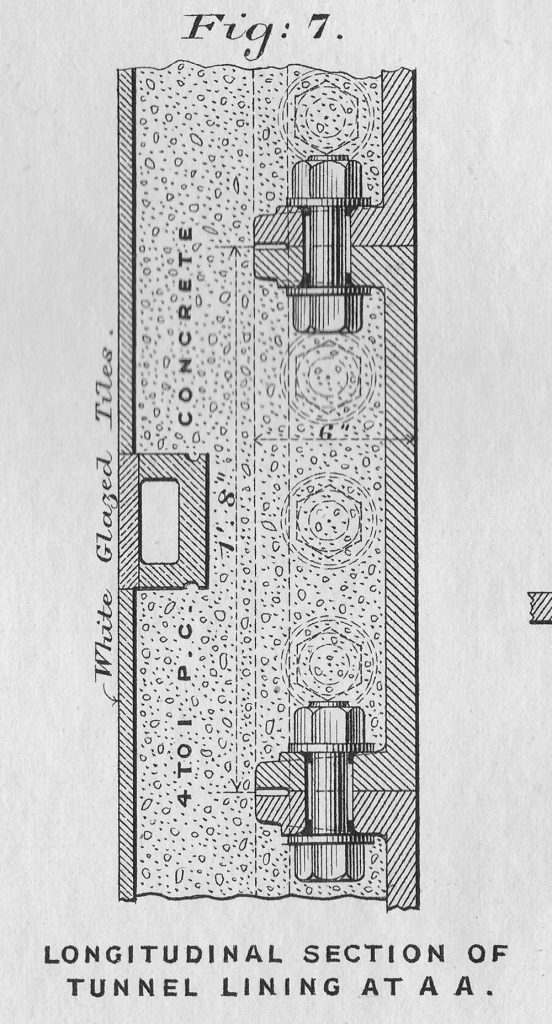

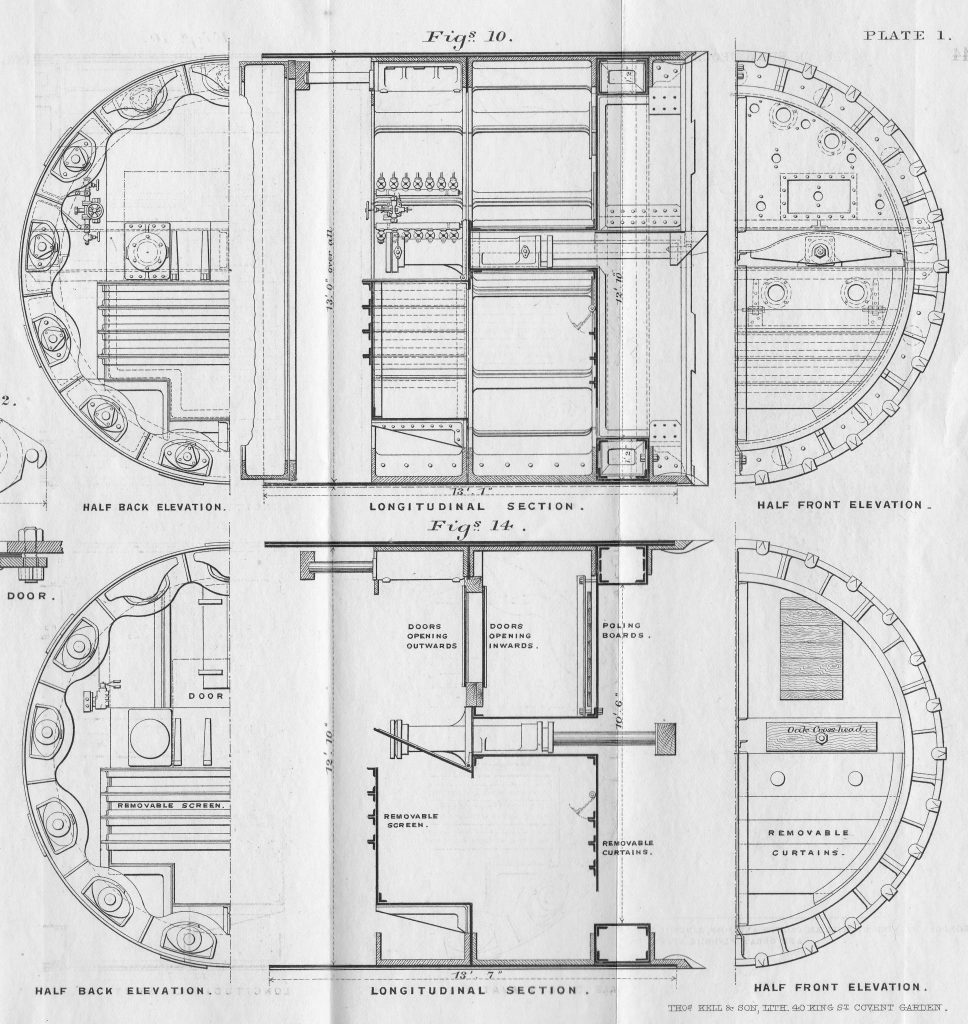

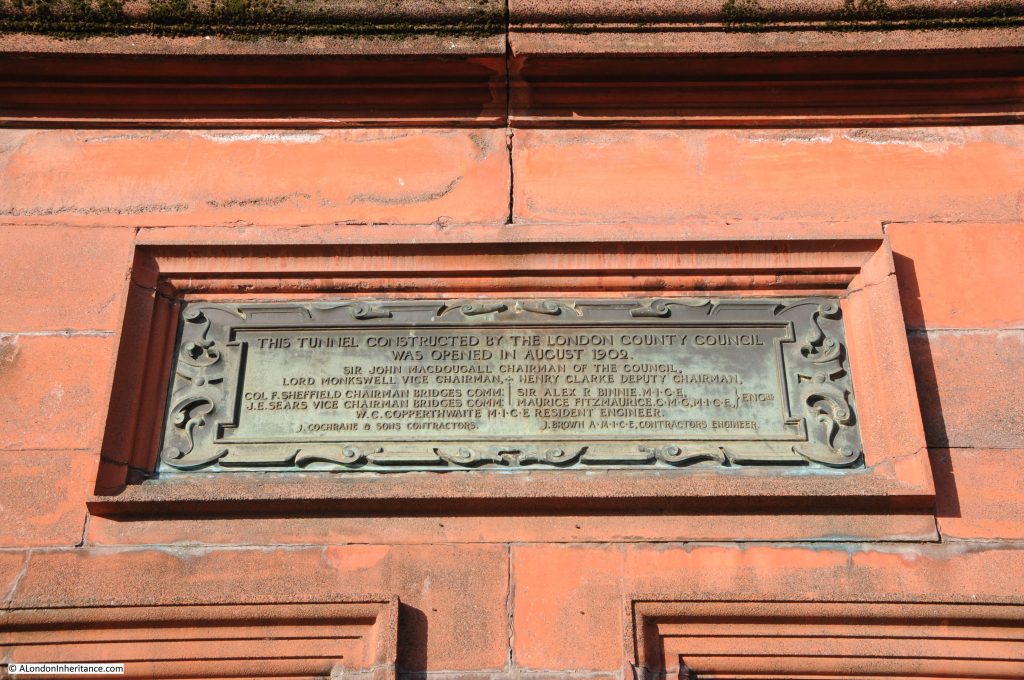

From the West Gate, I turn left and head down to the river, with the entrance to the Greenwich Foot Tunnel, which I have written about in a dedicated post, here.

An obligatory photo of the Cutty Sark:

From here I headed along the walkway by the river to find the locations in the Architects’ Journal map to the east of the Royal Naval College.

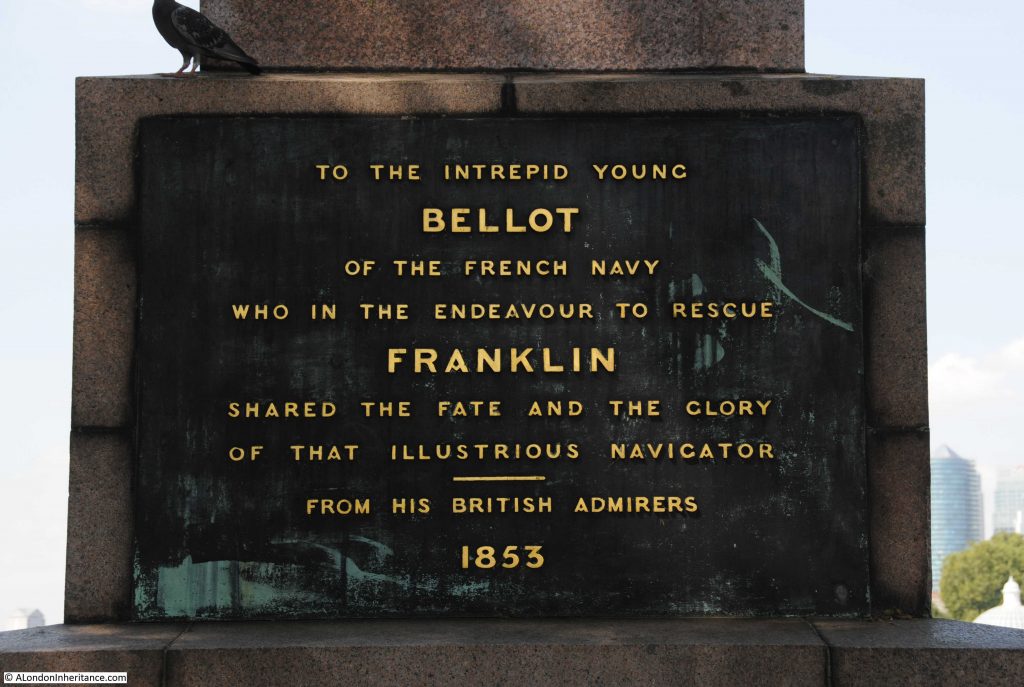

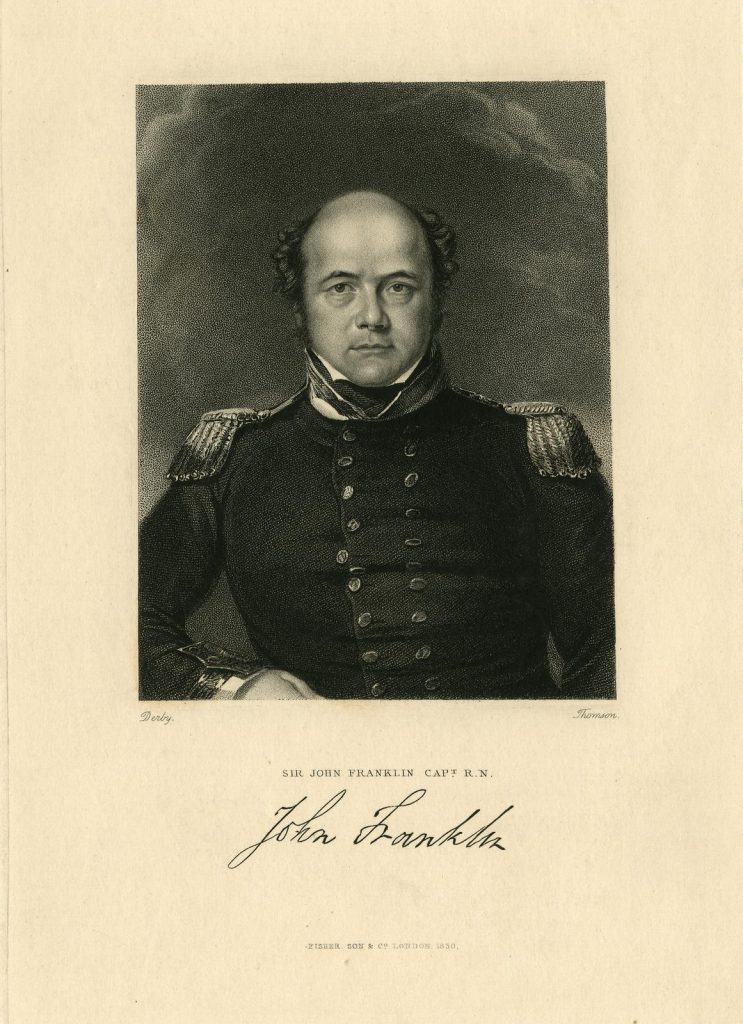

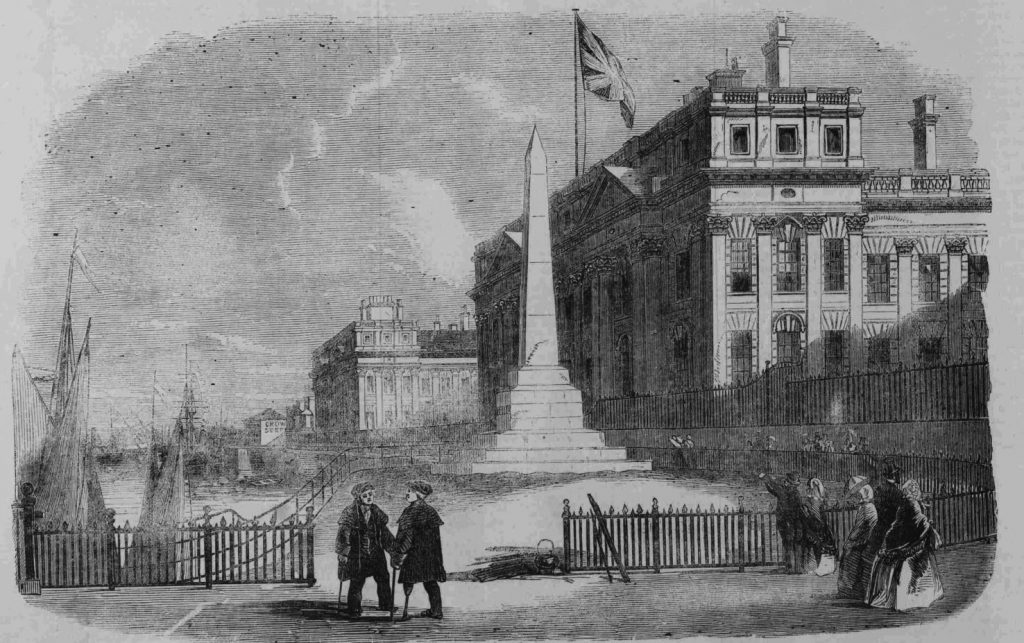

At the start of this walkway is the monument to a young lieutenant of the French Navy, Joseph Rene Bellot who went in search of Sir John Franklin. It is a fascinating story, and I have a dedicated post about Bellot, here.

Looking through the old Royal Naval College, to Queen’s House, with the Royal Observatory just visible on the hill in the distance:

At the end of the walkway alongside the river is the Grade II listed Trafalgar Tavern, which has a remarkable display of colourful flags outside:

Greenwich must have been a hive of building activity around 1830. As well as the market development and of the surrounding streets, the Trafalgar Tavern also dates from the same time. It was built on the site of an earlier pub, the Old George Inn.

The Historic England listing states 1830, however the pub website states 1837, and in this instance the pub website seems more accurate than Historic England as I found a newspaper report mentioning an event at the pub in 1833.

Crane Street alongside the pub was equally decorated, and it was along here that I walked to get to more sites on the Architects’ journal map.

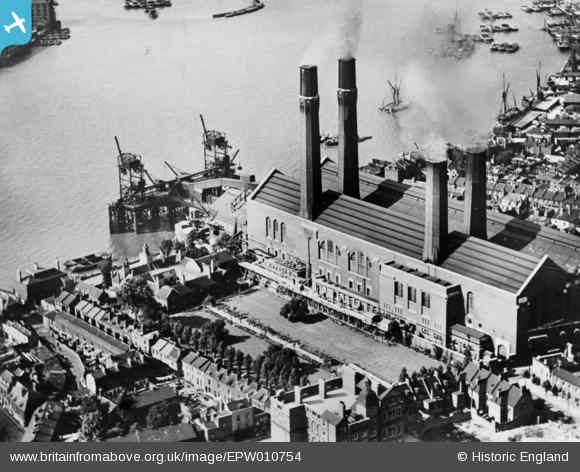

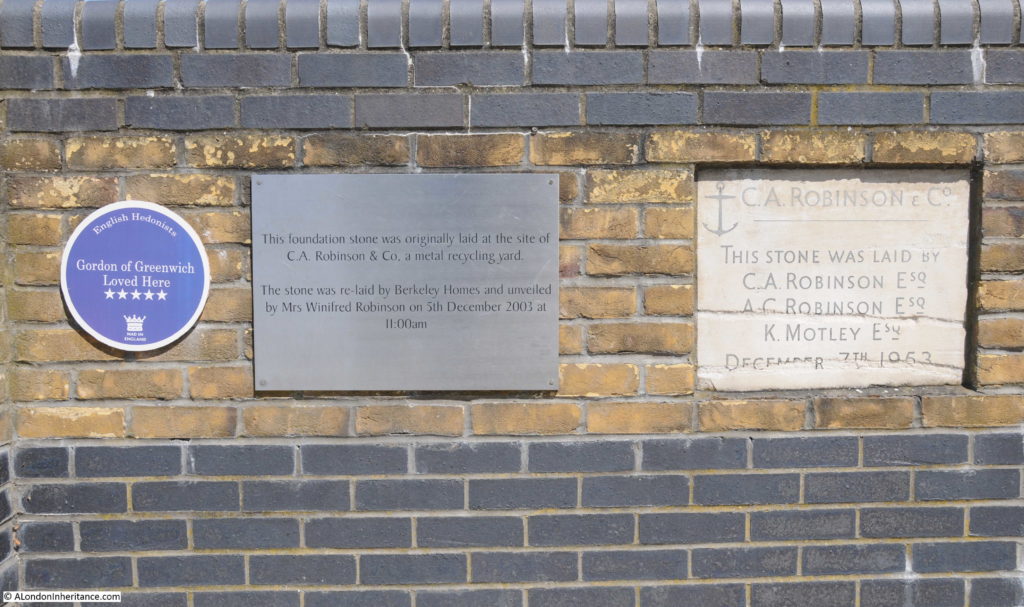

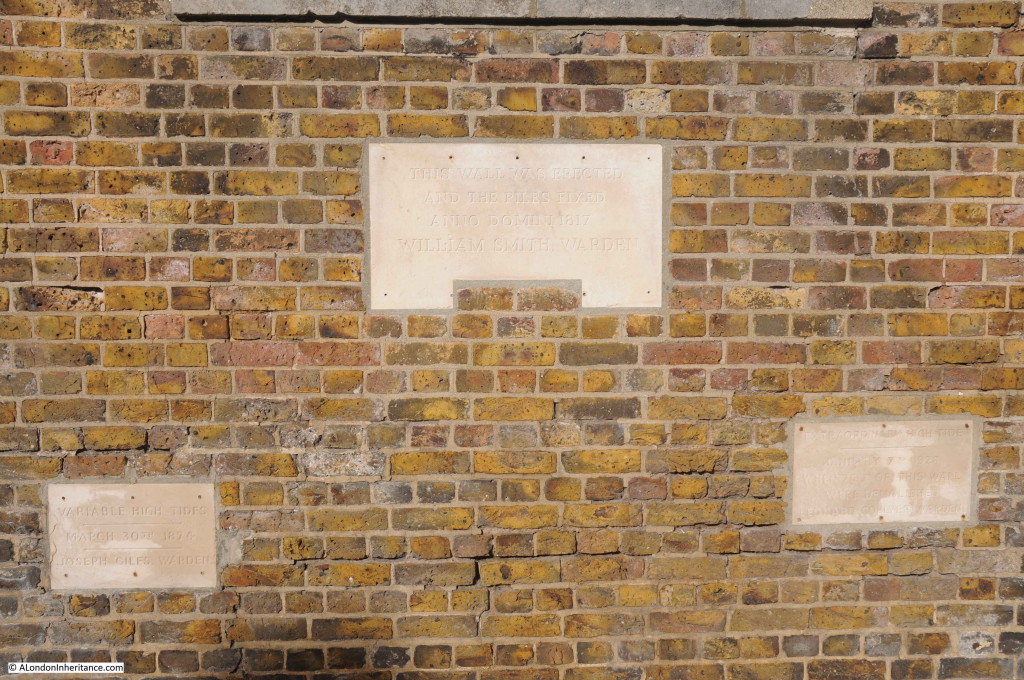

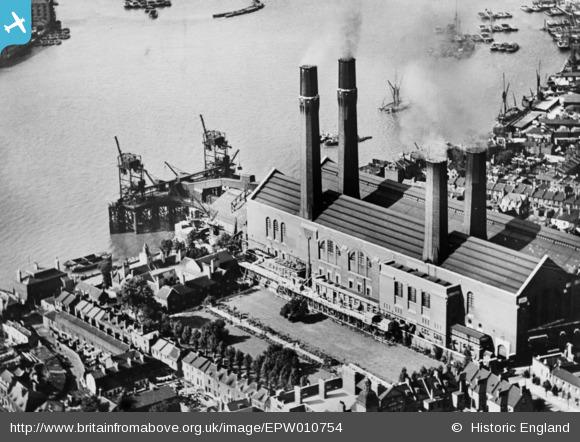

At the end of Crane Street is the (Grade II*) Trinity Hospital and Greenwich Power Station:

I have written a dedicated post about these two buildings, which you can find here.

In the Architects’ Journal map, Trinity Hospital is coloured black, indicating a building of concern, and one that should be protected from potential future development of east London, however the power station was not.

I suspect that if today there were plans to demolish the power station there would be a campaign to save the building. As well as part of Greenwich’s industrial history (off which there is not much left), it is also a major landmark, made prominent with the chimneys.

The power station is not listed.

View of part of the jetty where ships bringing coal for the power station once docked and unloaded:

Ships moored in the river:

Walking past the power station, I reached the eastern end of the Greenwich buildings in the Architects’ Journal map, which included the Cutty Sark pub (Grade II listed):

With the terrace of houses and at the end the Grade II listed Harbour Master’s Office for Ballast Quay:

I still had to visit the buildings shown on the map that are between the power station and Greenwich Park, so I headed back past the Cutty Sark pub, along Hoskins Street, where there is an interesting example of how most of a terrace was demolished leaving only two houses remaining.

The LCC Bomb Damage Map does show bomb damage here, so this may have been the cause of the loss of the rest of the terrace.

This is a very different part of Greenwich to that which I have explored in the first post and so far in this post. Here are the houses built for those who worked in the industries between Greenwich and Woolwich, and on the river, and the essential businesses that frequently occupy such areas:

Rear of the power station:

I do not know the purpose of the tower on the right. It may have been for water storage, but it looks rather small.

The road alongside the rear of the power station is the Old Woolwich Road, and as the name describes this was once the main route between Greenwich and Woolwich.

A nice reminder of the original purpose of the power station, and who consumed the electricity generated:

The rear of Trinity Hospital:

At the corner of Old Woolwich Road and Greenwich Park Street is the Star of Greenwich pub:

I really like the bay windows projecting from the pub on the two sides of the building.

The Star of Greenwich is a wonderful story of a pub saved from closure by the community.

A mid-19th century pub and originally called the Star and Garter, the pub closed in August 2021.

Three friends worked to reopen the pub as a community pub, a pub that would support a wide range of community services and would be an inclusive place for the people of Greenwich.

The pub reopened at the end of April 2023, and there is a BBC video about the pub, here.

A side street off Greenwich Park Street is Trenchard Street, which has some wonderful houses:

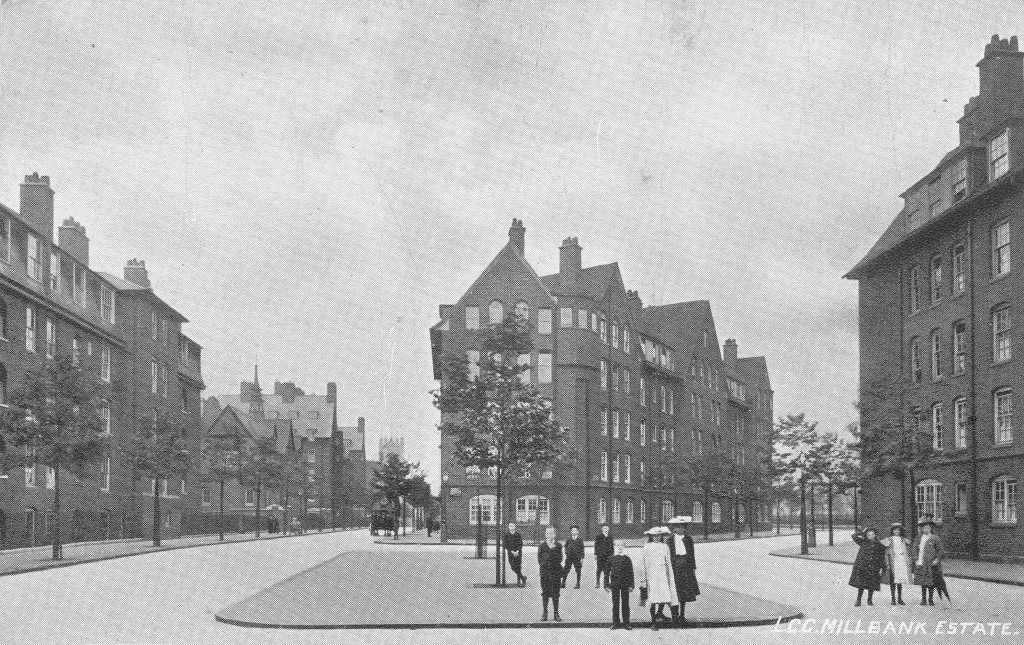

These houses, along with others in the surrounding streets are part of the Trenchard Street Estate, and were built by the Greenwich Hospital Estates from around 1913 and into the 1920s.

They are a considerable improvement on typical 19th century housing, and from the outside they can be seen as larger buildings, and have sizeable windows to let in as much light as possible.

At the end of Greenwich Park Street is Trafalgar Road, the main road today between Greenwich and Woolwich, and the road which replaced the Old Woolwich Road that runs at the rear of the power station and Trinity Hospital.

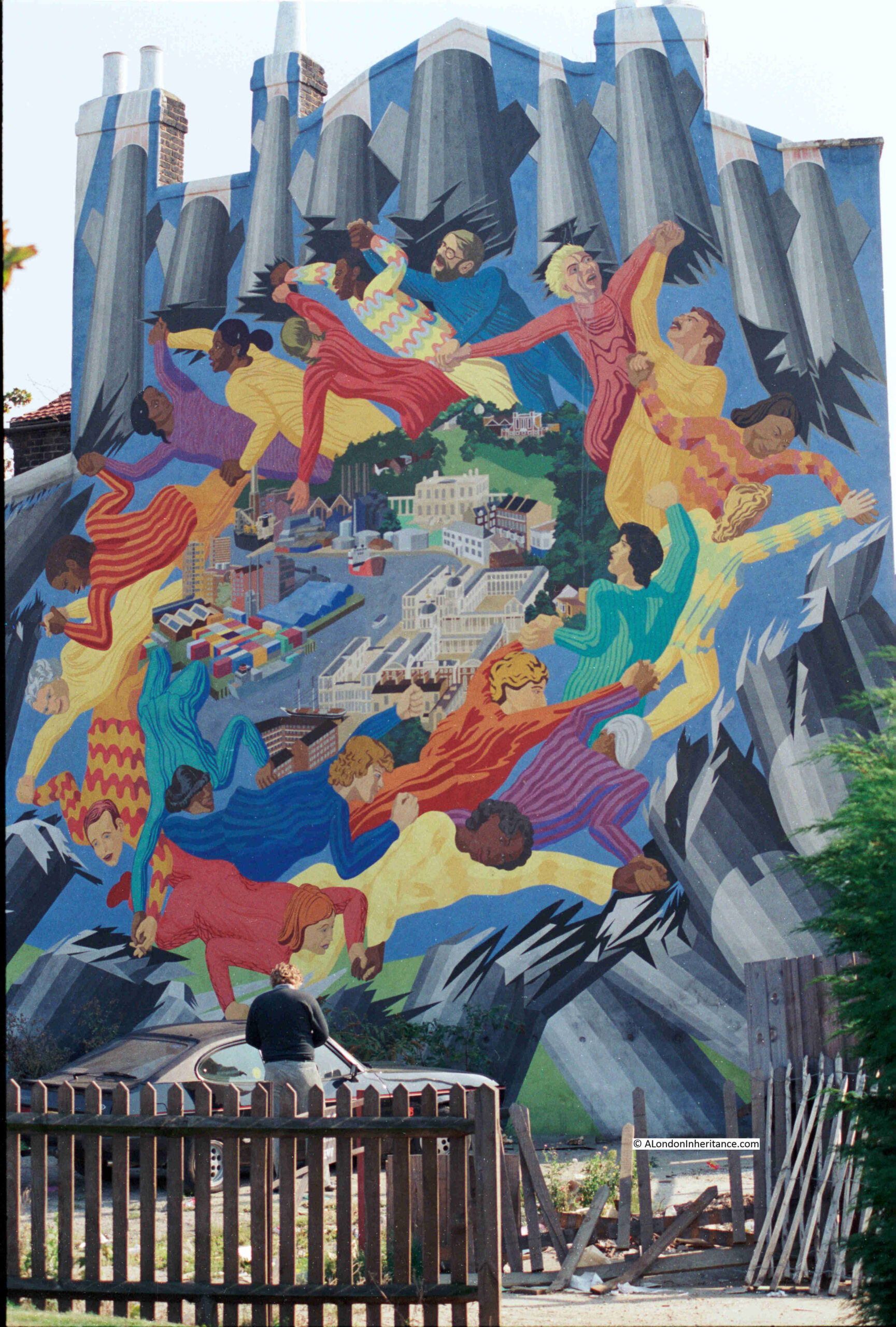

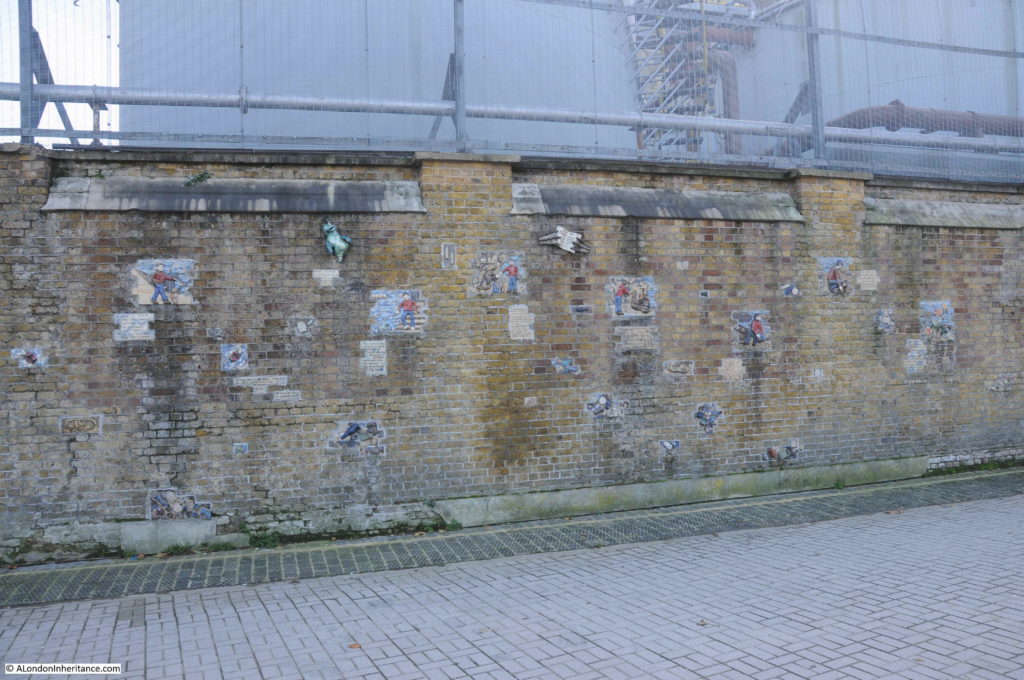

Mural on the side of a building alongside Trafalgar Road:

Crossing Trafalgar Road, and I am heading back to the northern side of Greenwich Park, and the proximity to the park can be seen by the type of house, which are generally larger and more expensive than those between Trafalgar Road and the river.

This terrace is alongside the southern section of Greenwich Park Street:

Park Vista runs along the northern edge of the park. There are no houses alongside the park, and houses line the northern side of the street, and as the street name suggests they have a wonderful view across into Greenwich Park.

The buildings are far from uniform, and show a wide range of styles and dates.

This is the Grade II listed Manor House, which the listing records as being early to mid 18th century:

The whole house is wonderful, however the roof has a unique feature, which the listing describes as “Hipped, tiled roof broken in centre to hold renewed weatherboarded gazebo with pyramidal, tiled roof.”

The gazebo is ideally placed for providing a view across the park, and would be a brilliant place for a summer evening with a beer.

In contrast is Park Place, dating from 1791:

To the west of Park Place is another Greenwich pub – the Plume of Feathers:

The pub’s website claims that it is the oldest pub in Greenwich and dates from 1691.

There is a small cluster of buildings in Samuel Travers map of Greenwich from 1695 in what seems to be the right place for the pub, so this could well be true. It is a really good pub, and well worth a visit.

Just past the pub, Park Vista curves slightly to the north, allowing houses to have been built between the street and park. A strange mix of styles, ages and later additions:

But one of these houses has a rather unique feature. There is a small square sign on the wall to the left of the lamp post in the above photo.

The sign refers to the Greenwich Meridian, and there is also a metal strip in the pavement:

Which continues with studs across the road:

So you do not have to join the queue for a photo of a foot in each hemisphere at the Royal Observatory, just head to Park Vista where you can take as much time as you want for photos.

The building at the western end of this cluster of houses is the Grade II listed St. Alfege’s Vicarage:

The listing starts the description of the building with “Rambling building of various dates”, although most of the building seems to date from around 1800, however at the very end of the listing there is the following “The old parts of this building formed part of Henry VIII’s palace of Placentia”, which is intriguing and would dates parts of the building back to the 16th century.

From here it was a short walk to the open space in front of the Queen’s House and the National Maritime Museum:

And just to show how everything has had some form of building work over the years, the large grassed area hides the cut and cover railway that runs underneath (part one of these Greenwich posts showed a view of the railway), as it runs between Greenwich and Maze Hill.

And from here there was only one place to go. It was a lovely sunny March day, so I headed back to the Cutty Sark pub, one of my favourite places to watch the river:

In these two posts, I have covered area 82 from the Architects’ journal map and list of places identified as worthy of preservation, and at risk of possible development as the east of London (north and south of the river) was expected to radically change in the following decades after the closure of the docks, and the loss of the industry and businesses associated with the docks and trade on the river.

From memory, there was never any significant risk to Greenwich, but the 1972 article has served as a reminder that Greenwich really is a wonderful part of the wider London.

Wander away from the park and there is plenty to be explored.