The last week has been really busy, and I am somewhat behind on post research, so for this week’s post I will revisit a set of books I have looked at a couple of times over the years, and discover some of the photos which show London in the 1920s, the 1926 book Wonderful London.

This was a three volume set, edited by the poet and novelist Arthur St John Adcock. The aim of the books was to show “The world’s greatest City. Described by its best writers and pictured by its finest photographers”.

The individual photos are not dated, however they must be from the years immediately before 1926, so these photos show London as it was 100 years ago – a very different place.

As the weather this weekend is forecast to be a hot one, I thought I would start with three photos from a set under the heading “London’s Annual Heat Wave Always Forgotten By The Next Year”

The following photo is captioned that “The road-menders seem uncomfortable at any time of the year”, which is a rather strange comment as the focus is on the hot temperatures – perhaps a miss-print.

It is always difficult to judge how far these were posed photos. The men in the above photo certainly look as if they have been asked to stand in a particular way, although I suspect that preparation for the photo did not go to the length of digging a hole in the road.

The following photo is of a man with an ice-cart, a job that involved pushing a cart around the city streets, loaded with a large block of ice, and making delivers to customers:

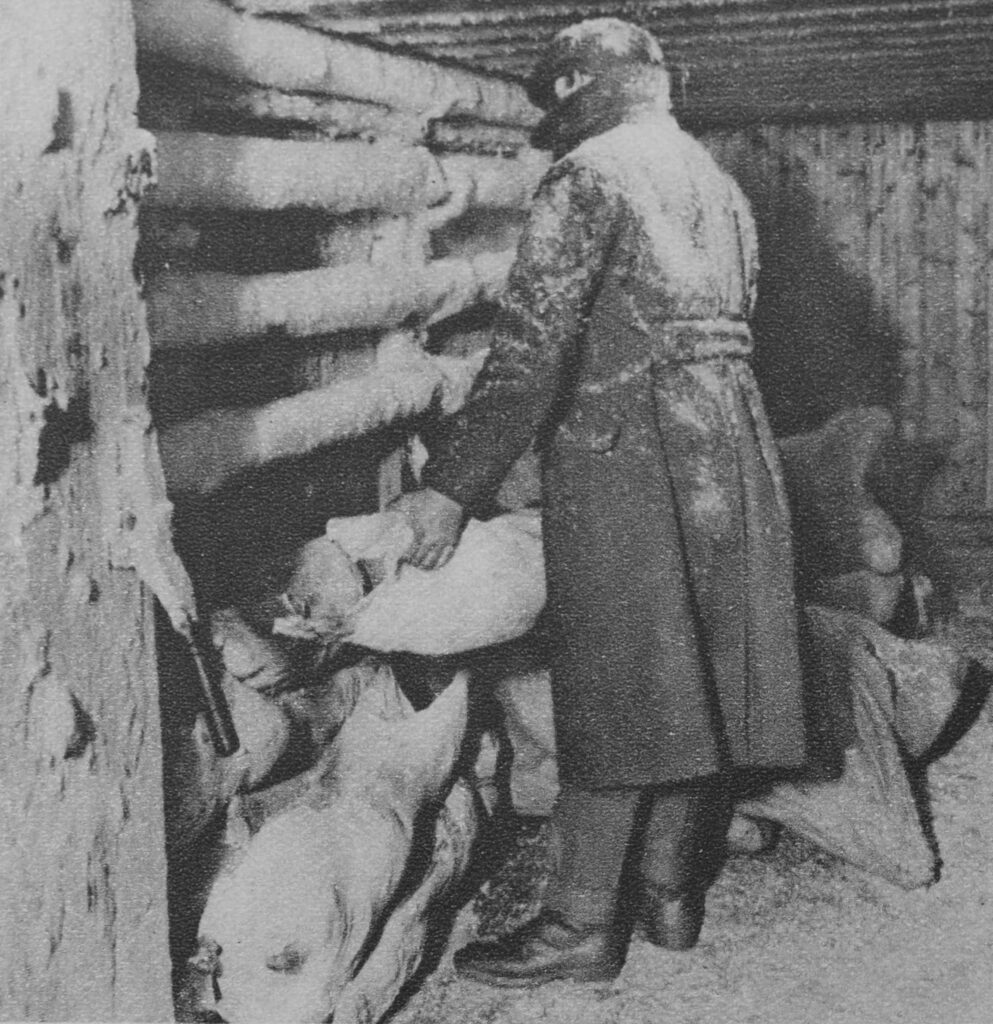

Whilst the above two jobs involved exposure to the heat of the city, the book shows a job that would be envied by those working across the streets on a hot summer’s day – the cold storage man, who was responsible for managing and moving the goods stored in a cold storage facility:

A typical summer sporting activity in London “Looking towards the pavilion from the Mound Stand at world-famous Lord’s”:

The books provide a bit of background history to many of the photos, and for the Lord’s photo, there is: “Lord’s the property of the Marylebone Cricket Club, consists of some 10 acres of property acquired at various times. The club originated at Finsbury, where it became known as the Artillery Ground Club. Cricket had been played there since about 1700. In 1780 the Artillery Ground Club moved to White Conduit Fields. There one of the attendants was named Lord. In 1787 the club ground was moved to Dorset Square and called Lord’s. In 1811 another move was made to a site near the Regent’s Canal, and in 1814 the final move to the present site. Lord took up and re-laid the turf at each move. the ground has a character of its own with the dignity of long establishment behind it which appeals to all Londoners.”

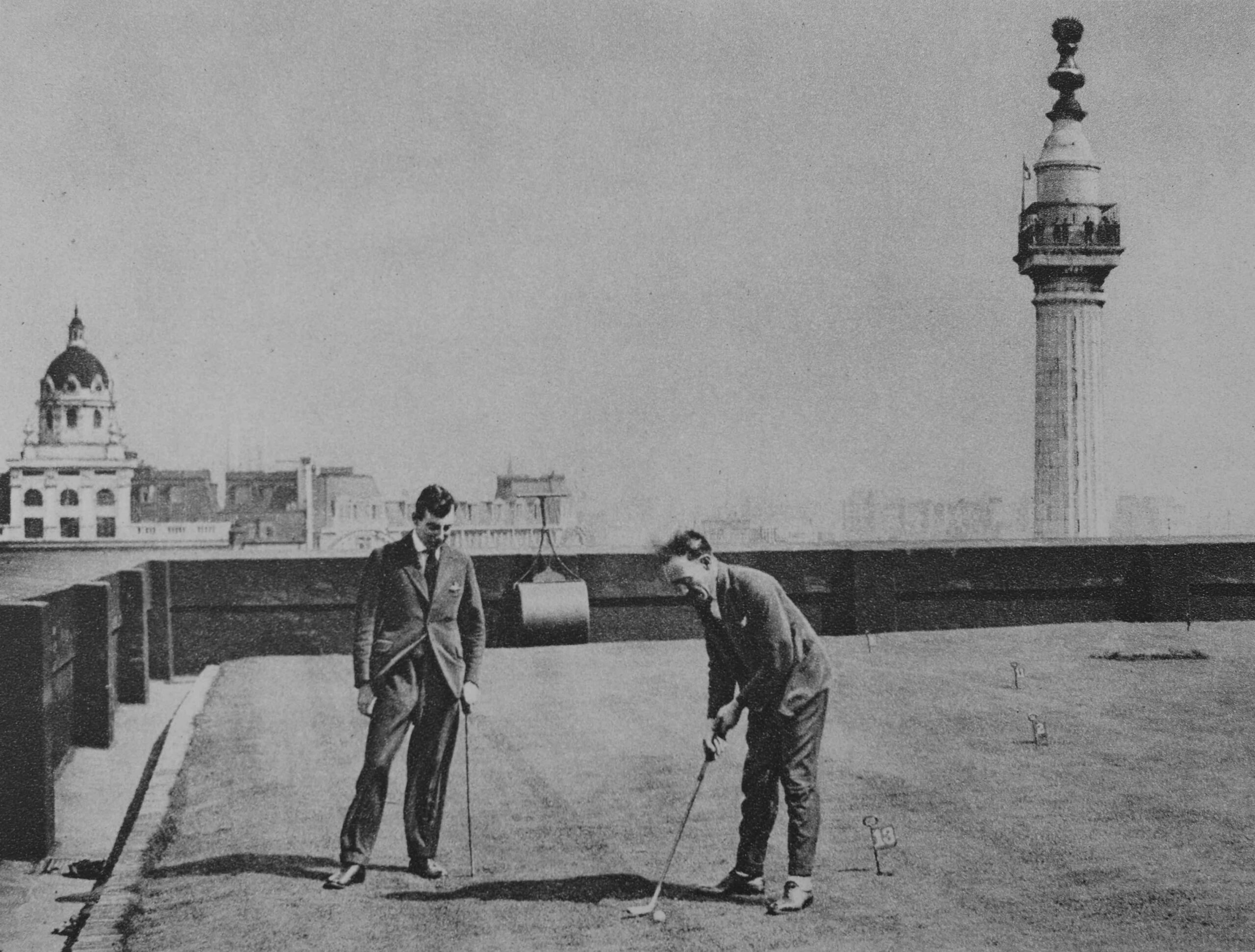

If your preferred game was golf rather than cricket, there was, what was described as “the only golf course in the City of London”. Not so much a golf course, but rather a putting green on the roof of Adelaide House, next to London Bridge. A building which is still there, and with the monument just behind:

The books include many photos of London’s streets as they were 100 years ago.

The following photo is captioned: “Turning south from Hammersmith High Road one walks down Hampshire Hog Lane, named after an inn at the corner, eventually reaches High Bridge, seen in the distance. this crosses the Creek, the mouth of the Stamford Brook, and is thought that the earliest settlement of Hammersmith centred here”:

Some of these photos can be a puzzle. For example, the caption to the above photo states that you turn south from Hammersmith High Road to walk down Hampshire Hog Lane, however Hampshire Hog Lane leads south from King Street. It did at the time of the photo and it does still.

Today, Hampshire Hog Lane is a small stub of a street. There is a pub on the corner as there was in the 1920s, the Hampshire, which is now more a restaurant than a pub.

You cannot walk down to where the bridge was, which has also disappeared, as has the creek. The Great West Road, the A4 has now carved across the southern part of the lane, and Furnivall Gardens now covers the location of the southern part of the creek and the bridge.

Although the scene in Hampshire Hog Lane has gone, the building in the following photo taken in Glebe Place, Chelsea can still be found. The book records that it “was probably a cottage used by factory hands in the employ of Bentley, Wedgewood’s partner”:

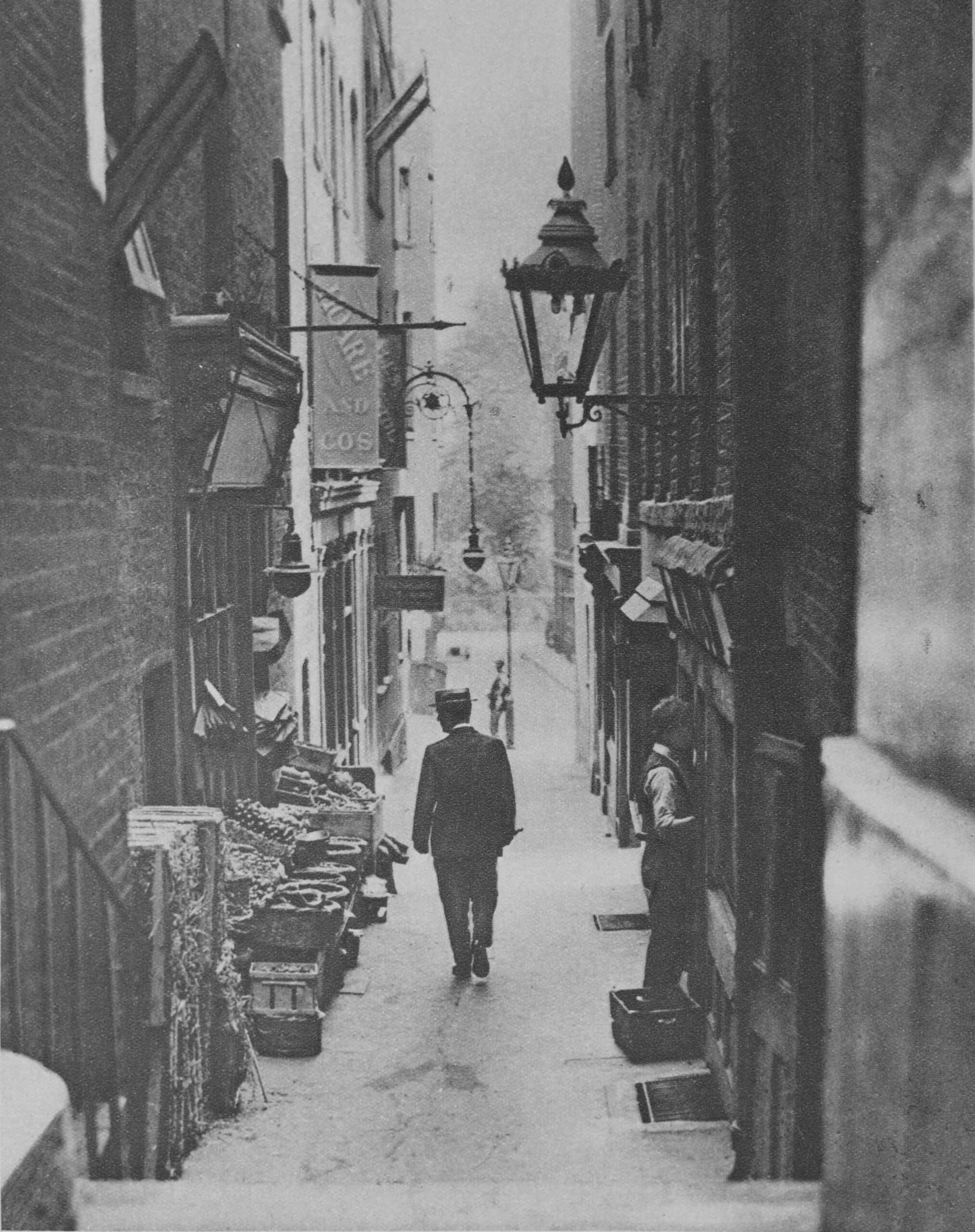

Streets in central London are also covered, with the following view of “George Court, an alleyway to the Adelphi from the Strand”. Very different buildings now line the alleyway:

Buckingham Palace has been seen on TV screens cross the world this year, however its only gained its current appearance just over 100 years ago – “George III bought Buckingham House in 1762 and in 1825 it was much altered by Nash for George IV. Edward VII was born here in 1841, and six years later the building was extended into a quadrangle. It then appeared as in the photo with an ugly and undignified frontage”:

The following photo of the palace as it is now is captioned “In 1913 Sir Aston Webb undertook to improve the one view that the public ever get of their King’s residence, with the result seen in the photograph”:

One of the trends in how London’s streets have changed over the years, is the grouping together of plots of land, and the construction of a large building on a plot which was once occupied by a number of smaller buildings.

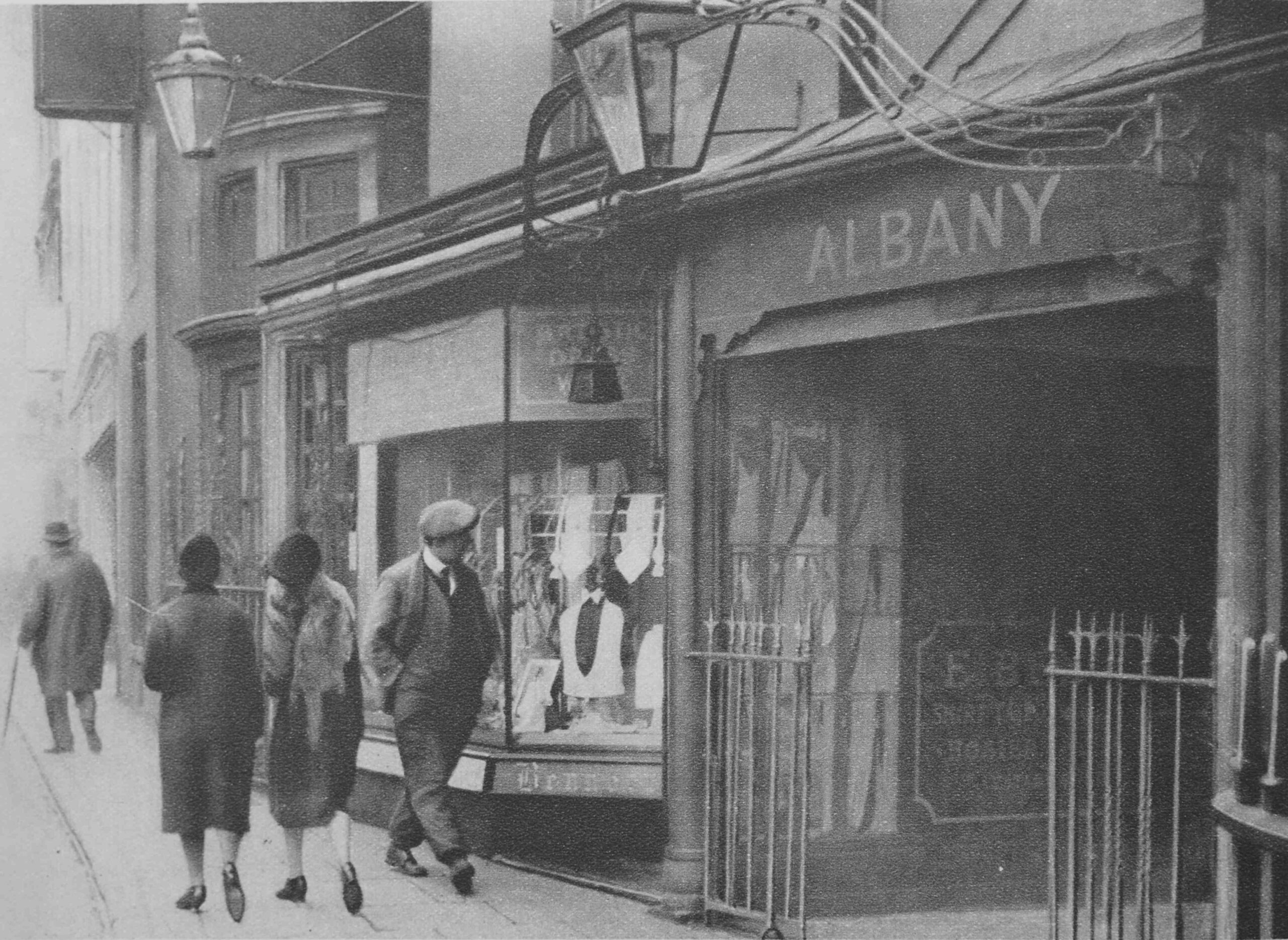

Such an example can be seen where the Albany meets Piccadilly. The Albany was a house occupied by the Earl of Sunderland in 1725, then the first Lord Melbourne acquired it and spent vast sums on the building, only to exchange it with the Duke of York, for a house in Whitehall.

The Albany was set back from Piccadilly, and approached through a narrow driveway. In 1926, this driveway was accessed through an arch leading through a building facing onto Piccadilly:

Today, the house is still there, however, the buildings seen in the above photo have been replaced by two larger buildings, and the access shown in the above photo has been replaced by a narrow, open street. It is opposite the bookshop Hatchards.

I suspect that as long as there has been photography, ‘Then’ and ‘Now’ photos have been a theme, and there were a number in Wonderful London. The following photo is of Oxford Street in the 1880s:

And the following is 40 years later in 1926, with included in the caption that “the only features of the old order left for the new are the two buildings on the right-hand side of the road and nearest the right edge of both photographs”:

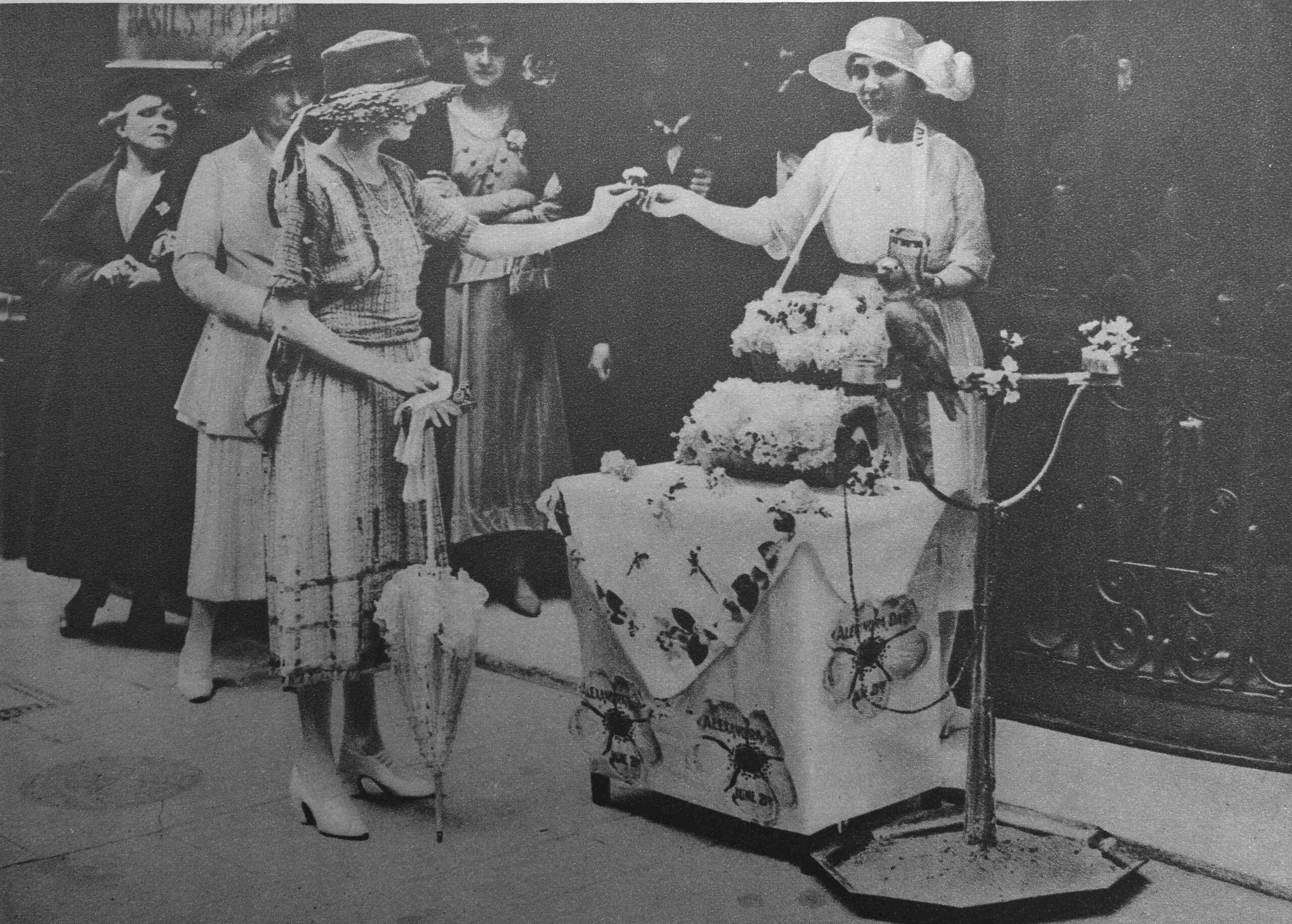

The following photo is titled “A Fine Morning In June: The Rose Day Of Queen Alexandra”, with the caption “Rose Day is an annual effort for raising funds for various charitable causes, including hospitals. it was founded by Queen Alexandra in the fiftieth year of her residence in England and persists after her death. The flowers used are made by blind and crippled workers and represent the dog rose, which was the Queen’s favourite flower. London’s streets are extensively patrolled by hundreds of ladies deputed for the task, who in return for two pence, or even a penny, will sell a rose – and a smile”:

The Alexandra Rose Charity is still running, and Rose Days ran between 1912 and 2012. Today, the charity is focused on providing “families on low incomes access to fresh fruit & vegetables in their local communities”.

Many of London’s markets feature in the books. The following photo shows the “Gracechurch Street entrance to Leadenhall Market – City Clearing House for Poultry”:

The book provides some historical background to Leadenhall Market: “In 1411 the Corporation of the City of London obtained the property of the manor of Leaden Hall from Sir Richard Whittington – of pantomime fame – who in turn had purchased it from the Nevilles. The market has flourished ever since, though the Great Fire destroyed it. The present premises date from 1881, when £140,000 was spent on new approaches alone. The market stands on the south side of Leadenhall Street with its main entrance in Gracechurch Street and Lime Street to the south”.

I was in Gracechurch Street a couple of weeks ago, and the main entrance to Leadenhall Market is getting somewhat over shadowed by the new buildings near by:

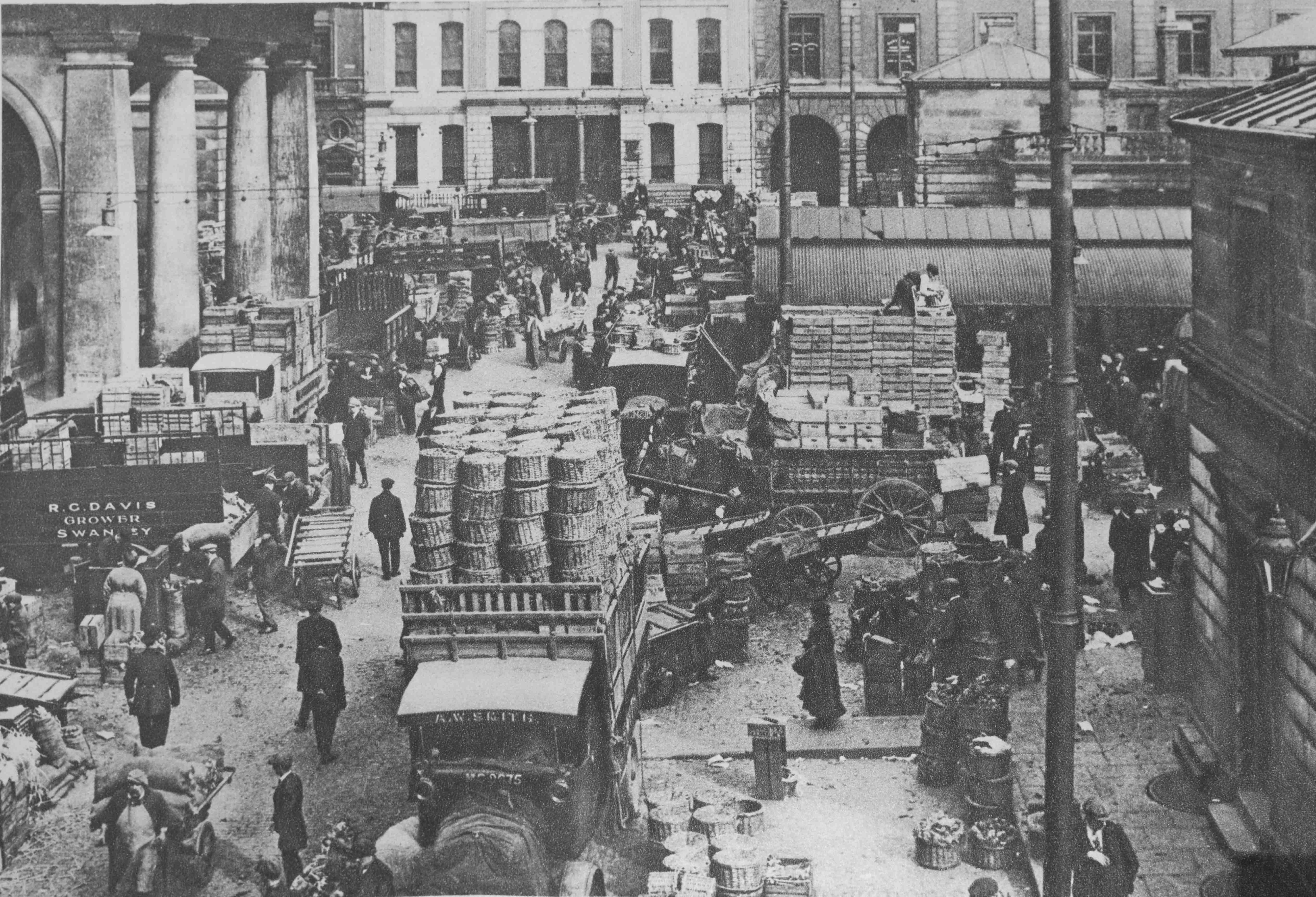

One of the other London markets featured in the books, is Covent Garden, with a view of “Stalls that display the products of many climes in the fruit department at Covent Garden”:

And this photo of “Early morning in the Covent Garden”, as “soon after their journeys from the market gardens beyond outer London to reach Covent garden in time”:

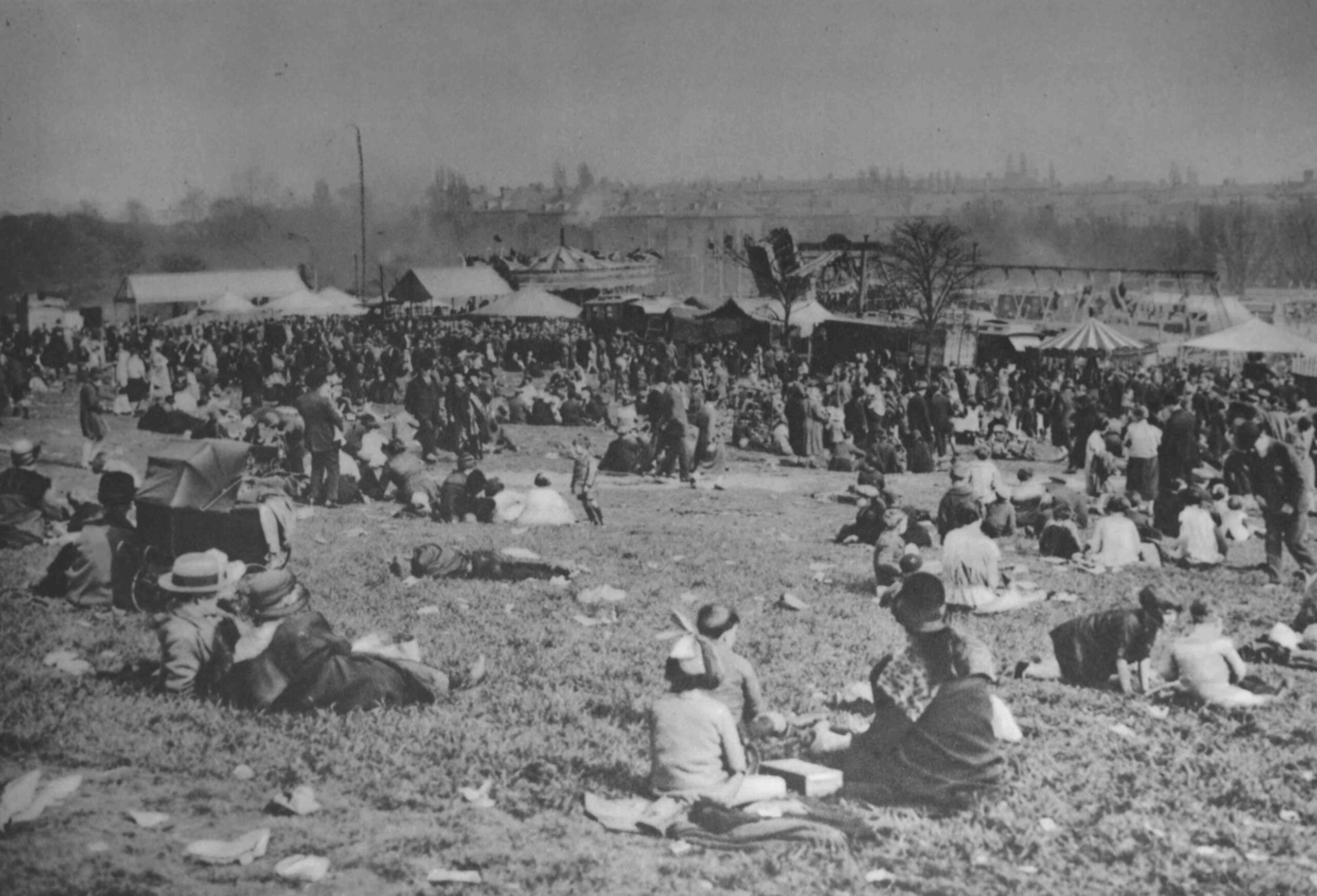

We just had a few Bank Holidays during May, and in previous Bank Holidays, Hampstead Heath would have been the destination of many Londoners seeking a day away from the streets of the city.

The description in Wonderful London of a Bank Holiday Monday on the heath, reads “It is a scene of riotous joy, the centre of promiscuous revelries. There are merry-go-rounds with loaded horses sinuously revolving, swings that thrill the most blasé patron, and booths where mild games of chance are played. Steam organs , wheezing and panting, grind out different popular airs simultaneously. Men shout, women scream, and children are cacophonous in every possible manner.

Performers on assertive musical instruments, particularly trombones and accordions, abound. The atmousphere is heavy with cheap perfumes, engine oil, the smell of cooking and sun-baked shell fish. Here Cockney London enjoys a ‘fresh air’ holiday.”

Although the book was highly critical of the result of these Bank Holiday revelries: “Garbage-littered tracks of the vandals who invade Hampstead Heath on every Bank Holiday”:

“On the day after a Bank Holiday dirty paper, empty cans, orange peel and banana skins give even the most Arcadian, the most freshly green avenues and glades of Hampstead Heath, and indeed all the parks and commons of London, an air of sordid debauch. The lover of open space is not so much angered by the site as filled with pity for his thoughtless fellow creatures. Many appeals have been made to the trippers, begging them not to cover the grass with rubbish, but all to no purpose. It is all the more extraordinary when we consider that all these defilers of natural beauty have a certain amount of education, and should be able to realize the ugly effects of carelessly throwing refuge in every direction”.

The above commentary to the photo is the most negative of any I can find across the three volumes of Wonderful London. There were many other aspects of London in the 1920s that could have warranted criticism, such as the working conditions of many of the city’s manual workers. poverty and the state of much of London’s poorer housing, but the focus was on the litter on Hampstead Heath.

If you did not want to spend a Bank Holiday on Hampstead Heath, you also had the option to go to Margate, by train:

Or by Paddle Steamer:

Here again the commentary is interesting: “It might be thought that the Cockney would want to have his holiday in the contrast of a comparative loneliness, but no! The first thing he does is to choose an August day, a platform hidden by moist humanity from which a dusty and uncomfortable train will take him to an almost equally crowded ‘watering place’. All this is lucky for the few others since England is not large enough for everyone to be by himself. A more ventilated way to is to go to Margate by boat from the Old Swan Pier just above London Bridge and opposite Fishmongers Hall.”

The commentary seems to lump everyone who was probably working class at the time as a “Cockney”. The commentary also ignores the fact that those who went on such trips often had extremely limited cash for a day away, did not have the time and opportunity to plan anything else, and probably went to places where they were accepted and catered for.

They did not have the means to plan or afford a trip which the lucky few could afford, such as – “All this is lucky for the few others since England is not large enough for everyone to be by himself.“

A couple of months ago I wrote a post about a tram route to Highgate, and included a bit about the Angel pub, not knowing that there was a photo in Wonderful London that included part of the Angel.

The following photo is looking down Highgate High Street (Pond Square is off camera to the right). The Angel is the pub on the right:

Assuming that photo was taken shortly before the books publication in 1926, it must have been one of the last photos of that version of the pub, as it was completely rebuilt between 1928 and 1930, with the pub we see today being the result.

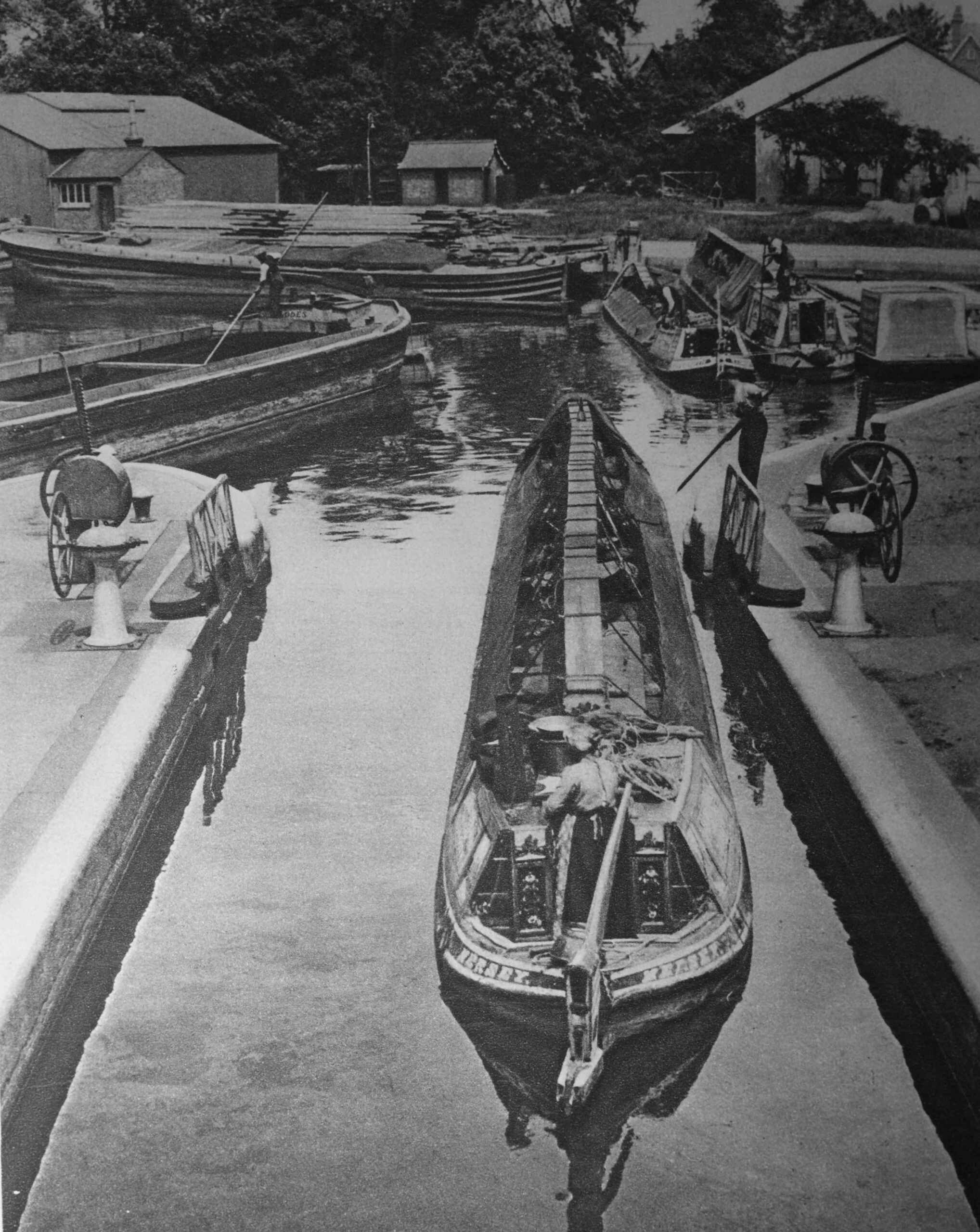

The book also includes a number of photos of life on the canals – a trade that must have been challenging and difficult given the significant decline in canal trade following the transfer of the movement of goods to the railways.

The book paints the people who worked on the canals in a somewhat idyllic light: “Some quiet moments of peaceful canal life”, and comments that “While employment as a whole in England tends to more and more hurry and less of that spirit now old fashioned, but which produced so much fine craftsmanship and an individuality which came to be associated with English craftsmen, yet it is pleasant to reflect that there is still one calling where contemplation is possible.

Here we see an old wife, born and bred on the waters, busily making fast the stern of her barge”:

“While the bargee and his mates are at dominoes in the hold”:

I doubt that the “old wife, born and bred on the waters” had much time for contemplation.

A horse could tow a cargo of twenty-five tons at about three miles an hour:

The following photo is titled “A Canal Washing Day”, and that “On the barges there is no room to stand upright in the cabin, and washing is done in the well. it is to be wondered what happens when it is raining on washing day”:

Barges on the canals into and around London would often carry goods to and from ships in the London docks. A profession that would dissapear in the decades following these photos.

The photo below is of a bargee pushing his boat through the lock at Brentford:

The books also feature some photos of the areas around the fringes of London. Places that were still rural, but were starting to feel the expanding influence of London in the 1920s.

The following photo shows some “elderly timber cottages hard by Hadley Green. the village atmousphere has survived even the advent of the villa and the bus”:

The following photo shows the Cherry Tree at Southgate (the pub which is on the right hand end of the terrace of buildings). The Cherry Tree is still there, as is the whole terrace. The streets in front of the terrace, the street furniture and the traffic look very different to this scene from 100 years ago:

These photos show a very different London in the 1920s. In the following 100 years, the city has changed dramatically. Buildings, street scenes, jobs, entertainment. It is only some of the buildings of state institutions that have stayed the same, such as Buckingham Palace.

It is fascinating to see the city in these old photos, but working with my father’s old photos has really emphasised to me that photos show a snapshot of the city at a specific point in time. London will always change, and someone in 100 years time, looking back on the city of today, will probably find what we take for normal, just as so very different as we view the 1920s.

The view of the entrance to Albany is not that from Piccadilly but at the other end of the site in Vigo Street, at the junction with Savile Row and Burlington Gardens. It remains virtually unchanged today physically but the two flanking shops are now rather smarter than they were then

Thanks Charles. I will update the post

The characters in the Albany pic are straight out of an Edward Ardizonne painting. He was a great chronicler of Lodon life.

in the pic of George Court what are the angled planes aboive windows?

Are they screens or reflectors of sunlight.

Oft seen never known for what.

Adelaide House was state of the art for commercial accomodation when it was built in 1925. Today, wellbeing is an accepted attribute of a new office block, but even then they had a ‘green roof’ for cooling and biodiversity, somewhere to exercise and a rooftop fruit and flower garden, with beehives.

George Court is part of the sequence of streets spelling out the name and title of the man whose C17 riverside house no longer exists: See also Villiers St, Buckingham St and the infamous Of Alley

Any old photos of the London Docks area, Wapping, East India. Poplar Isle of Dogs and Royal Docks Newham?

Yes, saving those for a dedicated post

Thanks

Paul Ridgeway – The angled planes above the windows were mirrors which reflected sunlight into the dark rooms.

The alleyways and courts from the Strand down to the river were named after George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham who owned a house there in C17.

An office block named Villiers House is on the Strand at the top of Villiers Street which is next to Charing Cross Cross Station.

To Sara James

Many thanks, all understood.

Regards,

PWR.

LOL! I can almost hear Harry Enfield’s ‘Mr Cholmondley Warner ‘ reading those passages about the terrible cockneys. Great post, many thanks.

In the roadworkers picture, the man on the far left is definitely on his mobile phone!

Wonderful post. Thank you.

I went to school in Southgate in the 1950s and early 1960s and passed the Cherry Tree in the bus regularly. In those days there was a green over the road, with a set of stocks in them (fenced off – not in general use!) I have no idea if they are still there

What a fascinating post not least for the insight into social attitudes of the time. We are lucky to have a number of books still available that give a good idea of what Old London looked like.

Fascinating as always.

Just as an aside, “Hampshire hog” is what natives of Hampshire are known as. This is in reference to the large number of wild pigs that roam across the New Forest.

The Glebe Place cottage subsequently became an “open-air” nursery school, probably because it has a much larger garden behind it than you’d expect from looking at the house from the front (though as I was only five at the time, my memories of it probably exaggerate the dimensions…). Glebe Place itself is fascinating architecturally for its mixture of purpose-built artists’ studios — from Chelsea’s nineteenth-century bohemian era — facing very large (and now eye-wateringly expensive) mid-Victorian terraced houses, and then leading to the village-like atmosphere of Lawrence Street, Cheyne Row, etc, much of which hasn’t changed since the eighteenth century and some of which appears in the opening scenes of the 1956 David Niven version of “Around the World in Eighty Days”.

It is incredible to think London changed so much in such a short period of time as we all know that London as an entity had been here for over two thousand years.

Also what is a sobering thought that I am 78 years age so a lot of those changes had occurred in my lifetime although the early part of my childhood was spent in Cardiff another city which has undoubtedly seen a lot of change. I wonder whether there is anybody in Cardiff running a blog like yourself on that city. Distance alone would preclude my involvement as I am now resident in the Scottish highlands. I would just like to say thank you for this as your interesting blog is now an established part of my Sunday morning routine.

Loved the tour. I remember the canals around South East London walworth. Thanks

An other great read and photos, thank you….

You queried the date of the Arthur St John Adcock books of which I have a full set o three. From the inscriptions in one of the book, although it does not bear a copyright date, I can see that my late paternal grandfather bought them in 1911. I never met him because he died in 1931 in a flu pandemic.

He was one of the survivors of the sinking of the HMHS Britannic in the Eastern Mediterranean on the 21st November 1916.

I remember poring over the books when I was a child, and my late father subsequently gave them to me, along with HV Morton’s “Ghosts of London”. It was these four books, and the “I-Spy book on London” which gave me my life long fascination. Two days after the Coronation in 1953 my Dad took me for a walk down the Mall, bedecked with all the coronation finery. I was going to send a photo of the three books, and the accompanying ones of Wonderful Britain, but there was no facility to send photos with this entry.

Please keep up the excellent work – it is a significantly better substitute for the dreary Sunday Newspapers.

Thank you for this – really fascinating.

I’ve just discovered your blog and will be reading with interest now.

Thank you so much. I spent ages enoying these photographs. I do feel a bit sad at the end though, since so much character has been lost in London.

My grandfather told stories of going ‘hop picking’ in the later WW1 years and after. He was born in Limehouse in 1904 and his siblings were born in Shadwell, Wapping and St George in the East. That was the only ‘holiday’ they got.

https://spitalfieldslife.com/2021/08/19/hop-picking-photographs-o/

Hi Keith,

Thought this link may be of interest to you regarding hop picking. Quite a few posts about it over the years on the site.

Thanks,

John

Keith Warren, this link may be of interest to you.

https://spitalfieldslife.com/2021/08/19/hop-picking-photographs-o/