Cheyne Row is an early 18th century street in Chelsea and is the location for this week’s post to track down the locations of two photos taken by my father in 1949.

The first photo is of the terrace of houses with a church at the end of the terrace where Cheyne Row meets Upper Cheyne Row.

The same view today:

The view has hardly changed, just cosmetic details such as the removal of the balcony on the house on the right, and the addition of a canopy above the door on the third house along. A single car was parked in the photo in 1949, today there is continuous parking along both sides of the street.

The church at the end of both photos has one of the longest dedications I have found – Our Most Holy Redeemer and St. Thomas More.

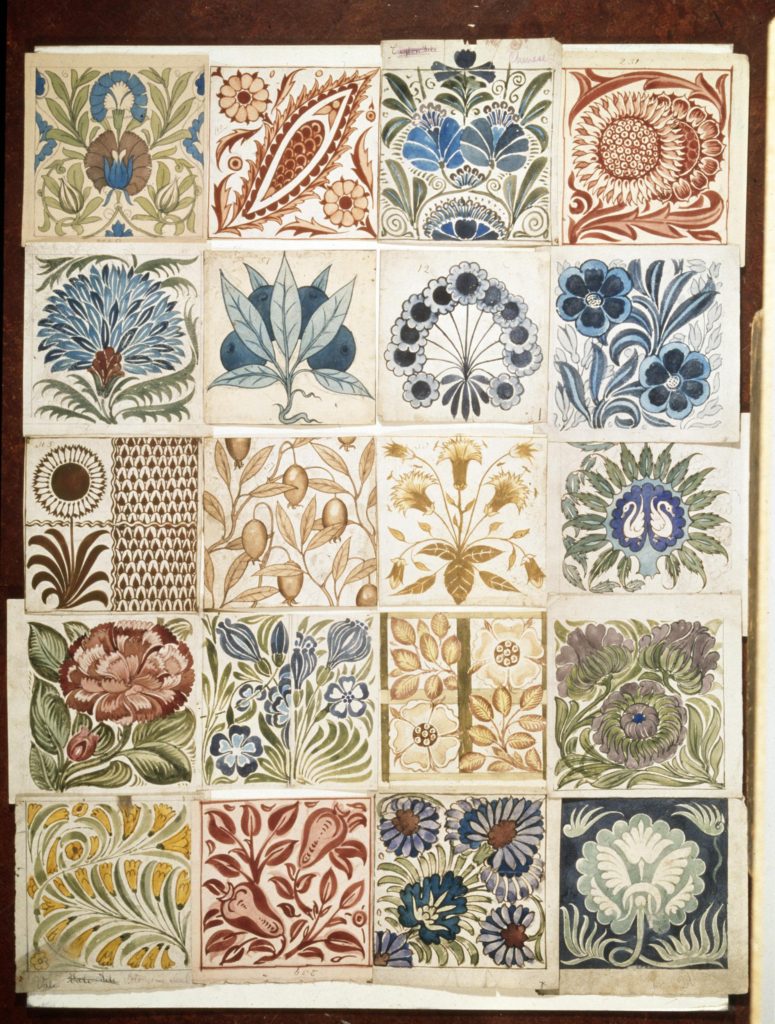

It was built between 1894 and 1895 on the site of the warehouse and showroom for the pottery run by William de Morgan who was in Cheyne Row between 1872 and 1881 before moving his pottery to Merton and then in 1888 to Sands End in Fulham. de Morgan was a friend of, and heavily influenced by William Morris. As well as pottery, he appears to have specialised in glazed tiles, very colourful and with intricate designs. The following picture shows a sample of his designs for decoration and ornament for pottery and tile work (© Victoria and Albert Museum, London):

In the 18th century, Chelsea was the location for a number of pottery businesses. Chelsea China was manufactured at a pottery in nearby Lawrence Street. Cheyne Row was also the location for Josiah Wedgewood’s London Decorating Studio. Pottery would be made at Wedgewood’s factory in Etruria near Stoke on Trent and brought down to London for final decoration before being sold to the affluent citizens of the city.

The main entrance to the church is on Cheyne Row and it extends back along Upper Cheyne Row. The crypt of the church was used as an air raid shelter during the 2nd World War. On the night of Saturday 14th September 1940, people were sheltering in the crypt when a high explosive bomb hit the church and exploded in the crypt. Of the 100 or so people in the crypt, 19 were killed by the explosion.

Despite the loss of life, the overall fabric of the church did not suffer major damage, unlike the nearby Chelsea Old Church which was completely destroyed in 1941 – see my post here.

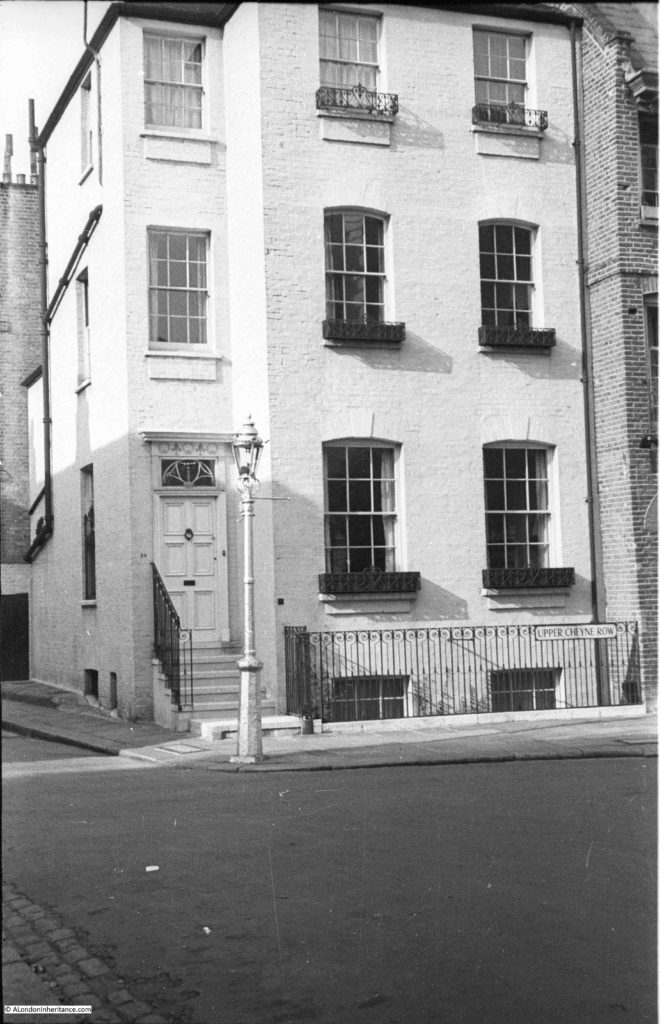

The second photo that my father took from Cheyne Row was from the end of the street, looking across to this building on the corner of Upper Cheyne Row and Glebe Place.

The same building today:

The key difference being that the white paint that covered the building in 1949 has been removed exposing the original brick work which, in my view, is a considerable improvement.

The only other change being the addition of the ornate ironwork at the sides and above the entrance from the street – the rest of the railings appear to be the same.

Cheyne Row was one of the first formal, residential streets in this part of Chelsea.

The street was built in 1708 on land that had been a bowling green belonging to the Three Tuns pub that was on the stretch of road facing the river.

Originally, the land had been part of the Manor of Chelsea, associated with the nearby Manor House which had been located to the west of Cheyne Row, just north of Upper Cheyne Row. The land and Manor House was purchased by Charles Cheyne in 1657. His son William inherited the estate, however he was also Lord Lieutenant of Buckinghamshire and preferred the country, so in 1712 William sold the Manor of Chelsea to Hans Sloane. The first part of Cheyne Row had already been built and named after the family that had owned the land for fifty-five years when the land was sold.

The following extract from John Rocque’s 1746 map shows Cheyne Row – the street in the centre of the map running up from the river with the solid black block of buildings on the right side of the street.

The map shows that the area was mainly gardens and orchards in the middle of the 18th century. The street running along the river ends at the junction with what is now Royal Hospital Road. The numerous stairs to the river, the boats on the river and the ferry landing points show that the river was probably the fastest and safest way to travel to central London from Chelsea.

To the right of Cheyne Row and towards Oakley Street (which now runs up from the Albert Bridge) was Shrewsbury House, another of the Tudor manor houses along this stretch of the river. Shrewsbury House was demolished in 1813, however the western boundary brick wall of the grounds associated with the house still forms the boundary wall at the end of some of the gardens of the houses on the eastern side of Cheyne Row. Tudor bricks from the house and boundary walls can also be found in the walls around this part of Chelsea.

Stone plaque from 1708 recording that this is Cheyne Row (although the more I look at the plaque it looks like Cheyne Ron): The house with the 1708 plaque is on the end of the original terrace of Cheyne Row houses, the other end of the terrace are the houses shown in my father’s first photo.

The house with the 1708 plaque is on the end of the original terrace of Cheyne Row houses, the other end of the terrace are the houses shown in my father’s first photo.

In the middle of this terrace is Thomas Carlyle’s house:

Thomas Carlyle was a Scottish philosopher, historian and writer, born in 1795 he moved to London with his family in 1831 before moving to Cheyne Row in 1834 where he would stay until his death in 1881. His wife, Jane, was initially concerned about the location, that being so close to the river the area would be foggy in winter, damp and unwholesome. The rent for such a large, solidly built house was low, only £35 for the first year as the area at the time had become rather unfashionable.

The house is owned by the National Trust. On the front of the house is a plaque erected by the Carlyle Society.

Thea Holme, the actress and also author of a couple of excellent books, one on the “The Carlyles At Home” and the second “Chelsea” which is a detailed history of Chelsea, lived in Thomas Carlyle’s house in the 1960s whilst her husband was working for the National Trust as the curator of the house.

The junction with Lordship Place is roughly a third of the way up Cheyne Row from the river end of the street. The buildings to the left of this junction are the first to be built and were originally houses with single digit street numbers. For example Carlyle’s house was originally number 5 but is now number 24. This change in number was due to the additional building in the street and changing the numbers in what had originally been the section furthest from the Thames (also originally called Great Cheyne Row) to a single set of street numbers starting from the junction with Cheyne Walk.

The buildings to the right of the junction with Lordship Place leading down towards the river are of three storeys but are slightly smaller than the upper section of the street.

The second terrace house in the photo above, the one with the strange dummy window on the first floor has a round plaque between the windows on the ground floor:

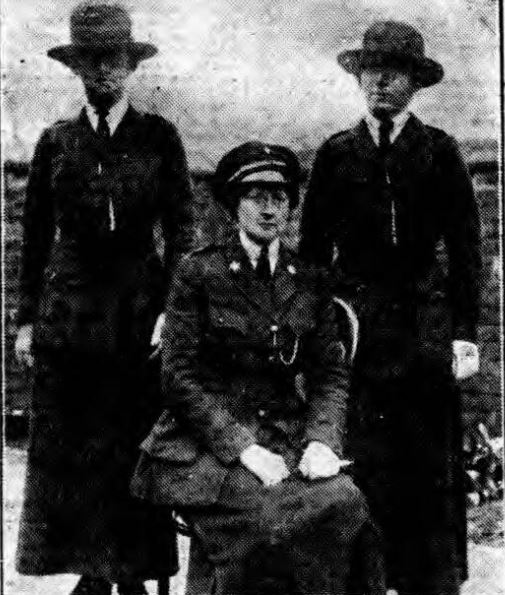

The plaque records that Margaret Damer Dawson lived in the house in Cheyne Row. Margaret Damer Dawson was a fascinating figure during the first couple of decades of the 20th century.

She was one of the founders in September 1914 of the Women Police Volunteers, which evolved into the Women Police Service, and which grew significantly during the First World War. As well as her interest in the police service, Margaret Damer Dawson was also a musician, a climber, motor-cyclist and a strong anti-vivisectionist.

The obituary published after her death in 1920 provides an interesting view of her achievements and of London during the First World War:

“The late Miss Margaret Mary Damer-Dawson OBE, whose death was announced last week, rendered valuable service to the young women of England by her work in connection with the Women Police Force of which she was Commandant.

The writer of a personal tribute in ‘The Times’ says her death came as a great shock to those who had known and worked with her. Woman of a naturally fastidious mind, she faced the realities of life with such courage that her work was of far more use than that of a woman of coarser fiber could have been. The most feminine of women, with a gentle voice and quiet manner, she yet went further than other uniformed women in adopting the outward symbols of male authority. She cut her hair close to her head, a fashion in which many of her inspectors followed her, and it was the rule of her force that superior officers were addressed as ‘sir’.

With the outward symbols, however the apparent masculinity disappeared. Everything that was young found in her a protector; she protected ‘khaki-mad’ young women from themselves, and she protected country-bred, ignorant young men, brought into big camps and great cities from harpies of all kinds. But especially was she the young woman’s friend. She was not of those who believed that it was only a young man who could sow his wild oats and then go straight; she believed that the young woman could pull herself together equally well, and she was entirely opposed to those who seem to think that sack-cloth and ashes and laundry work are the only possible means of redemption for a girl who has decided to give up a bad life.

Many girls who had strayed into the West End, had become known to the police, and had then tired of their life and wished to reform, found in her a useful and sincere friend. She had a gift for finding jobs for many protegees and girls who came to her, knowing her practical sympathy, rarely failed to make good. And even the failures she did not blame; for she knew that circumstances and the present state of the law were against them. One particular case moved her very strongly and she often told it as an example of how the fates played against her. A girl whom she had helped, and who had been accustomed to being in the West End at night, found ill-paid work in a factory near King’s Cross. A girl whom she knew on the streets sent her word that she was fallen ill and was penniless in lodgings near Leicester Square. the former was crossing the square to see her when a policeman who knew her, saw her and arrested her for accosting. On the policeman’s evidence the girl was imprisoned, and this nearly broke Miss Damer-Dawson’s heart. for the girl, when she came out, declined to work any more, as she refused to believe that once a women was known to the police she could never make good again.”

One of her motivations for founding the Women Police Service was her shock in discovering in 1914 that Belgian refugees from the Germans were being enticed into the sex trade by pimps and gangsters, often as they arrived as London’s train stations.

As well as support of the police service which was short of offices due to the war, the Ministry of Munitions employed members of the women’s police service to search women munition workers when they entered and left munition factories.

At the end of the First World War Damer-Dawson asked the Chief Commissioner of Police to make the Womens Service a permanent part of the police force, however he refused, apparently stating that the women were “too educated” and would “irritate” male members of the police force.

Magaret Damer-Dawson was awarded an OBE for her work with the Women Police Service during the First World War. She is pictured here, seated in uniform:

In the gardens that run alongside Cheyne Walk there is also a bird bath commemorating Damer-Dawson:

For a change, my walk around Cheyne Row was in lovely autumn weather, with sunshine highlighting to advantage the buildings that line the street. As well as the terraces of three floor houses, there are also buildings of very different styles showing that this is a street that has evolved since the first building in 1708, however despite these very different styles, they all seem work well together.

I mentioned Thea Holme earlier who lived in Carlyle’s house. In her book Chelsea, she talks about walking in Cheyne Walk and finding a foreign tourist looking lost and asking for “Chelsea”. She gradually comes to understand that by Chelsea he means the King’s Road, and then ends this story with the paragraph:

“But is there a Chelsea still which is not the King’s Road, which has not only a heart, but a spirit? Where is Chelsea, the Chelsea whose fame grew from century to century, spread abroad by the people who fell under the spell of this ‘Hyde Park on the Thames’? it is still on the Thames, though separated from it by an ever-increasing flow of traffic. It still has a beauty of water and sky, and the remains of nostalgic antiquity.”

Perhaps it was the lovely autumn weather, but I agree, it is easy to fall under the spell of this part of Chelsea.

It’s interesting to note that at some point after 1746, Beaufort Street turned through 90 degrees. Rocque’s map has it running alongside the river, whereas today it runs north-south between Battersea Bridge and Fulham Road.

As always an interesting read,thank you

Illuminating. As are the photographs. Sublime quote of Thea Holme on Chelsea.

A really enjoyable and informative read. Now I want to visit this area when I’m next in London!

I came across your blog while researching some family history, looking for 15 Cheyne Row. The relatives living at this address with their young daughter were Salvation Army Officers. Do you have knowledge of a Salvation Army Church or Centre in this area around 1890-1900? I find it a curious juxtaposition, don’t know why!

I look forward to reading more of your work.

My great grandparents got married cheyne row r.c church Chelsea in 1915 were can I find information in this

Great memory of growing up in this area and around the 1970s having friends living in a house on the east side near the river end of Cheyne Row. We would often hear VERY loud rock music coming from the back of Mick Jagger’s home on Cheyne Walk. The rear of Mick’s house coming up to the back garden of my friend’s home. Not sure if he was playing loud records or was practicing with the rest of the Rolling Stones – we liked to believe the latter!

By any chance do you have anything on the old Pier Hotel which used to stand at the corner of Cheyne Row and Oakley Street, East of Shrewsbury House. I remember waiting for the 49 bus to go to school at the bus stop out side the Hotel on Oakley St. After the hotel was demolished, it was for a while a vacant site and there were some kind of “Food Wagons” there. One made Belgium Waffles and I remember eating them piled high with jam and whipped cream with my Mother and Sister. Pier House was eventually built on that site and my younger sister and I shared a flat there after she finished University and we were some of the earliest residents before it was even fully sold and occupied.

Also, there used to be a Sweet shop and also a Delicatessen either in the bottom of the Pier Hotel or some shops right next to it at the very left end of Cheyne Walk at the corner before Oakley Street. Any pictures of this area? I can’t even seem to find anything on the Internet about the Hotel.

Thank you for your marvelous posts I am indulging myself in reading lots of them over this Christmas Holiday.